by Arne De Boever

“Never believe that a smooth space will suffice to save us.” (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 500)

Smooth Sovereignty

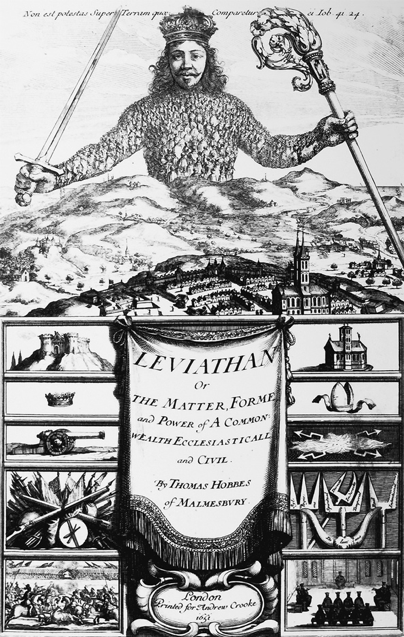

To begin, consider for a moment one of the most famous images of sovereignty, the frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan:

Intended to capture Hobbes’ social contract theory in a single image, the figure of the Leviathan that is shown here finds its raison d’être in Hobbes’ theory of the state of nature. Roughly, and speaking in a way that I will have to nuance later, state of nature theory posits that in the beginning, people (I hesitate to write “humans”) were living in a state of nature. Pessimistic theorists of the political—like Hobbes–envision this as an undesirable state in which people are like wolves to each other (hence, my hesitation).[2] Optimistic theorists of the political think otherwise. In both cases, people eventually come together to draw up a contract–hence, Hobbes’ renown as a contract theorist–to determine how they want to live together. This contract is a set of laws or a constitution by which a group chooses to live. The group thus institutes what Hobbes calls a Leviathan, Commonwealth, or State, an artificial man who represents them. Such a Leviathan is designed, in Hobbes, against the possibility of civil war, but the fear that the state of nature might erupt again is always there in the Hobbesian model. We therefore live in fear—of both the civil war and of the sovereign who is meant to hold it at bay.

The frontispiece of Hobbes shows all of this. It shows a figure of sovereignty—I again hesitate to call it an actual human being—spectrally hovering over a landscape. It is unclear where this figure is standing, whether it is part of the landscape or not. Certainly, it resides outside of the walls that mark the town over which it looms. In its right hand, the figure holds a sword, symbol of earthly power. In its left, it holds a religious staff, symbol of spiritual power—and note that the staff appears to reach into the landscape over which the sovereign rises. With the exception of the head and the hands, the body of this sovereign is made up of the bodies of its subjects—those who instituted the sovereign and find themselves represented in the body of the king.[3] They all look up towards the sovereign, who gazes outside of the image, at the reader. This image needs to be read vertically: starting with the Latin quote from the book of Job at the top (“there is no power on earth that compares to him”), one lowers one’s gaze towards the bottom half of the image, which is split between images of earthly power on the left and images of spiritual power on the right. In the middle hangs a curtain, perhaps hiding where the sovereign is standing (its feet, as has been shown,[4] would likely rest precisely where Hobbes’ name is written on the curtain).

Now consider Michel Foucault’s reading of Hobbes in “Society Must Be Defended”. Foucault forces one to adjust the state of nature narrative. The state of nature is not one of perpetual, actual war in the way we have imagined it. The problem in the state of nature, Hobbes suggests (according to Foucault), is “equality” (Foucault 2003, 90). People are too equal in strength; there isn’t enough difference. And this leads to a “primitive war” as “the immediate effect of nondifferences, or at least insufficient differences” (Ibid.).[5] “If there were great differences, if there really were obvious disparities between men, it is quite obvious that war would immediately come to an end” (Ibid.).[6] Why? Because it would be obvious who the strong are, and who the weak are, and either there would be a clash and the strong would win, or there would be no clash because the weak would be smart enough to refrain from engaging in one (See: Ibid., 91). To live peacefully, people need to institute inequality or difference. This is how the sovereign comes about—a radically unequal power, marking absolute difference. “Differences lead to peace” (Ibid.). This gets people out of the state of nature and its petty war of representations, its “anarchy” (Ibid.) and “theatre” (Ibid., 92) of minor differences.

Hobbes has three models of sovereignty: one by institution (people come together and close a contract, institute a sovereign) (Foucault 2003, 93); one by acquisition (one country violently conquers another, which is defeated) (Ibid., 94). Interestingly, Foucault points out that while we would call the latter conquest (“domination” [Ibid., 95]), for Hobbes it is ultimately not because the defeated will institute the new sovereign, will accept the conqueror as their sovereign. Why? Because they want to live. But this is not a biopolitical will to live: it is institution bound up in fear (of death—we are firmly within the realm of sovereignty) (See: Ibid., 96). Hobbes compares the latter form of sovereignty to (and this is the third model) the child’s dependency on their mother: they depend on the mother to live, or rather to avoid death (See: Ibid., 96). On this basis, Foucault presents Hobbes as a theorist against war, as a theorist of peace who took war as his fundamental adversary in his work (See: Ibid., 97). Hobbes sought to “eliminate” (Ibid.) war from politics. According to Foucault, he theorized what I will call here—overstating the case somewhat–a smooth sovereignty.

Foucault then mobilizes (See: Foucault 2003, 99 and after) English political history to drive a rift into Hobbes’ work. He refuses for the violence of conquest to be swept under the carpet. He practices a political historicism against Hobbes’ state of peace. He follows the Levellers and the Diggers et cetera in their attempt to keep revolution and rebellion—“war against the state”, as Melinda Cooper in her reading of the lecture specifies (Cooper 2004, 516) –alive. There is always an alternative; the norm was violently put into place. In sum: Foucault takes it up for war against Hobbes as a theorist of peace.

At the very end of his lecture, Foucault attacks “dialectical materialism”, evidence that he is working through his relation to Marx in his Collège de France lectures (as Stuart Elden for example has shown [See: Elden 2016]). Jacques Bidet, author of Foucault With Marx, explains that likely what Foucault is attacking here is a “‘Hegelian’ Marx, thinker of the totality and its historical unfolding to the point where social contradictions are overcome” (Bidet 2016, 4). Foucault’s attack, at the end of the lecture on Hobbes as a theorist who seeks to eliminate war, may be against a Marx as a “Hegelian” thinker who ultimately sweeps the negative under the carpet.

There are plenty of other reasons, Bidet goes on, why Foucault may have taken up Marx in this context: Marx’ account of politics, which focused on class struggle and the economic determinism that triggered it, was simply not nuanced enough for Foucault to paint an adequate political picture. Bidet notes much later in his book Foucault’s criticism of Marx’ use of the word “struggle”, which “passes over in silence precisely what is meant by struggle” (Bidet 2016, 127). This in particular resonates with Foucault’s criticism of Hobbes as a theorist against war. Bidet writes that in Foucault’s view “Marxism ultimately neutralizes [the “politics is war”] paradigm by performing a dialectical operation on it: at the end of the revolutionary process, after the final reversal of economic domination, antagonism comes to be re-absorbed within a new contractual order of joint concertation among all. But Foucault refuses this final utopia” (Ibid., 173-174). “Under the new form of state domination, he discerns the war that is begun ever anew” (Ibid., 174). “The Marxists’ dialectic”, in Foucault’s view, “occults the fact of war” (Ibid., 175).

I intend to comment elsewhere on how all of this makes Foucault appear as somewhat of a Schmittian–and Bidet indeed writes of “Foucault’s wink to Carl Schmitt, for whom the fundamental [political] category is also that of war” (Bidet 2016, 176) –, who seeks to keep alive a political pluriverse—against[7] Hobbes, who defends a political universe. When it comes to a concept of the political, Foucault’s reading of Hobbes shows that he is more with Schmitt than with Hobbes. In order to accept such a wink, however, one has to overlook at least one important difference between Foucault and Schmitt. When it comes to Foucault’s advocacy of politics as war, Foucault is recuperating from Hobbes a war against the state; but that is crucially not what Schmitt advocates. (As Chantal Mouffe points out, Schmitt locates the enemy outside of democratic association. He doesn’t think a democratic pluralism within [See: Mouffe 1999, 5].[8]) The source of Foucault’s concept of the political may not so much have been Schmitt, but the Black Panther Party, as Brady Heiner Thomas has argued (See: Thomas 2007). Melinda Cooper remarks on this difference to reveal, as she puts it, “some provocative points of intersection and discord” between Foucault and Schmitt, leading to the conclusion that in fact Foucault and Schmitt “were engaged in a violent argument with each other” (Cooper 2004, 515). There is no doubt, I think, that she is right.

The reason I have rehearsed Foucault’s reading of Hobbes here, however, is to show how Foucault, in response to what he perceives to be the theorization of a smooth sovereignty in Hobbes, takes it up for a theory of sovereignty that has to be rooted in friction. Whenever there is sovereignty, there is war; “There is no escape” (Foucault 2003, 111), as Foucault writes, from this political and historical fact. From the Diggers’ understanding that “[l]aws, power, and government are the obverse of war”, summarized powerfully in the line “Government means their war against us; rebellion is our war against them” (Ibid., 108),[9] Foucault ultimately arrives at this conclusion:

Yet the fact remains that you see here the first formulation of the idea that any law, whatever it may be, every form of sovereignty, whatever it may be, and any type of power, whatever it may be, has to be analyzed not in terms of natural right and the establishment of sovereignty, but in terms of the unending movement—which has no historical end—of the shifting relations that make some dominant over others. (Ibid., 109)

We have here then a powerful refutation of any understanding of sovereignty as frictionless—of any theory of smooth sovereignty, as I called it earlier on.

But what are the consequences of such a position for the political concept of sovereignty? Below, I intend to address that question through a case-study that can be productively analyzed in the framework laid out above: the situation of black lives in the United States today. As my reference to Brady Heiner Thomas already revealed, this situation is historically inscribed in Foucault’s theorization of politics during the mid-1970s, through Foucault’s (unacknowledged) encounter with race relations in the U.S. and the writings of the Black Panther Party. What follows is an attempt to write in the tracks of that inscription.

After a brief reading of Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me that focuses on the presence of sovereignty in that book, I seek to negotiate specifically the continued relevance of sovereignty for the situation of black life in the U.S. today. Following Achille Mbembe’s theorization of necropolitics, I distinguish between two sovereign inscriptions of black life within sovereign power: one associated with Hegel’s dialectics, the other with Bataille and the break with dialectics. I then turn to Frantz Fanon and Mbembe’s reading of Fanon (in Critique of Black Reason) to show how this tension between Hegel and Bataille can already be found in Fanon’s plea for absolute (rather than dialectical) violence, which is however formulated as part of a constructive call for national liberation that would rein this violence back in. That said, the constructive element of Fanon’s project was hardly conservative in any straightforward way: he had in mind a national liberation based on the creation of a new man, one that thus preserved traces of both the Bataillean and Hegelian inscriptions of black life in sovereign power that Mbembe distinguishes. “Sovereignty” in Fanon must be negotiated between those two traces. (It’s also worth adding, as I will discuss below, that the relation between black life and sovereignty may very well exceed both: neither Hegelian dialectics nor Bataillean transgression, perhaps the para-ontological understanding of blackness can find political meaning here as a continuous unsettling that’s neither with Hegel nor with Bataille, and as such precisely—as David Marriott has argued–non-sovereign [See: Marriott 2016].)[10] Mbembe’s “critique” reveals this negotiation between Hegel and Bataille as well in that it appears to be torn between a more conservative articulation that would remain within critique’s limits, and a more radical one that would seek to transgress them—a transgression that, in Bataille, nevertheless remains sovereign in name. It is perhaps that nominal remainder of sovereignty that indicates that the risk of transgression is great: indeed, in his most transgressive moments, Mbembe also risks to promote (as I intend to show) the kind of exceptionalist sovereignty that Coates’ work exposes.

More than 50 years after the founding of the Black Panther Party in 1966, and at a time when the “horizontalist” Black Lives Matter movement is violently clashing in the U.S. with both the status quo and new “vertical” formations on the Right, this article asks whether there can be a future for sovereignty when it comes to black life in the U.S.? Can there be an Afro-Futurism of sovereignty? Can Fanon’s call for national liberation and the articulation it was briefly given in Black Panther politics still take on new meanings today? Can there be a dream of sovereignty—and it is worth emphasizing that sovereignty, to a certain extent, is always a dream–that is not a white Dream? Who are its dreamers? What might they dream? Such questions seem particularly important today, when sovereignty has reemerged on the Right. Liberalism is exhausted. Sovereignty is making a come-back as part of a repoliticization against liberalism, and neoliberalism (though this last point is contestable[11]). But where is this sovereignty going to go? Unless the Left participates in this conversation and contributes to rethinking sovereignty from within, they may not stand a chance against the Right’s revitalization of sovereignty’s old specter. In closing, I consider how an alliance between African-American and Native American politics may in spite of their differences prove to be productive on this count.

State of Exception and Necropolitics

In his book Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates shows, although he does not use these terms, that black life in the U.S. is caught up in a state of exception (See: Coates 2015). In his discussion of black life’s exposure to sovereign power, he focuses on the pair black life/police in view of the ongoing police shootings of young black men—in some cases, children–in the U.S. As Coates notes, perhaps the most troubling element apart from these people’s deaths, is that they are killed with impunity: “These shooters were investigated, exonerated, and promptly returned to the streets, where, so emboldened, they shot again” (Ibid, 78). It is the element of impunity that clearly renders black life in this situation “sacred”, in Giorgio Agamben’s understanding of this term: outside of human law, exposed to be killed without legal consequence (“vogelfrei”, as I have argued elsewhere [See: Boever 2009]). It is this element that turns black people’s “fear to rage”: the fact that the murderers “cannot be subpoenaed … will not bend under indictment” (Coates 2015, 83).

That we are talking about a situation of sovereignty here is partly made clear in Coates’ text through the specifics of the police killing that he focuses on, which involves an officer from Prince George’s County (in Baltimore state) and a young black man called Prince Carmen Jones. Prince Jones is shot one night, while going to visit his fiancée, by a cop who claims Jones was trying to run him over with his jeep. Jones had been approached by the cop, gun drawn; the cop had been undercover, in other words was in plain clothes, and had shown no badge. He was, in other words, “a man in a criminal’s costume” (as Coates points out [Coates 2015, 81]), and Coates confesses with horror that “I knew what I would have done with such a man confronting me, gun drawn, mere feet from my family’s home” (Ibid.). The suggestion is, presumably, that he would have done the same: he too may have tried to run over the cop. The point about the “criminal’s costume” is sharpened a few pages later, when we finally find out something that Coates obviously knew from the onset: “The officer who killed Prince Jones was black” (Ibid., 83).

It is hard to overlook the sovereign overtones of the confrontation (one prince versus another). To be clear: while Coates presents the lives of young black men to be caught up in a state of exception, he also insists that in the U.S. this exception has become the rule. “In America,” he writes later on, “it is traditional to destroy the black body—it is heritage” (Coates 2015, 103). In other words, America is another name for a place where the state of exception of black life has always been the rule. It is another name for what Agamben, working with a European frame of reference that ignores the situation of black lives in the U.S. entirely, calls a camp: any situation in which the exception becomes the rule. The police, indeed, “reflect America in all of its will and fear”, as he notes earlier on, “and whatever we might make of this country’s criminal justice policy, it cannot be said that it was imposed by a repressive minority. The abuses that have followed from these policies—the sprawling carceral state, the random detection of black people, the torture of suspects—are the product of democratic will” (Ibid., 79). The charge, if we put Coates and Agamben together, is harsh: democratic America equals black Auschwitz. Or, without Agamben’s frame of reference: slavery never ended.[12]

In the Prince Jones killing we confront the particular perversity of black Auschwitz, namely black-on-black violence, which is fuelled, Coates suggests, by what he calls “the Dream”. By this, he means the white people’s Dream, the Dream of a white America. He calls those who share such a Dream, “Dreamers”. Black people in the U.S. carry not only “the burden of living among Dreamers”; they also have the “extra burden of your country telling you the Dream is just, noble, and real, and you are crazy for seeing the corruption and smelling the sulfur” (Coates 2015, 106). Perversely, it is “the Dream” that may in part explain the black-on-black violence that Coates is analyzing closely: it is “the Dream” that may explain the cop’s reaction to Prince Jones, in the same way that it is “the Dream” that may explain Jones’ reaction to the cop. Part of the “criminal’s costume”, in other words, and one can hardly call it a costume, is the blackness of both the victim and the murderer—a blackness that “the Dream” criminalizes and that makes black people kill each other due to the white people’s racist fear. When Coates shudders in horror at the realization of what he would have done—the same–, he is also shuddering in horror at the extent to which “the Dream” has infected him, the extent to which it has turned him against his own people. Between the World and Me is an attempt to puncture this “Dream”, to force something between the reality of Coates’ life and the psychotic construction of “the Dream” in which it is caught up.[13] In Between the World and Me, Coates is attacking a white sovereignty not just in terms of the physical violence that it wields but in terms of the psychic phantasy that backs it up.

To be a black man in the U.S. means that the police “had my body, could do with that body whatever they pleased” (Coates 2015, 76). Coates ties this situation to the history of slavery in the U.S., and thus to the history of European colonialism and the relentless and ongoing “plunder of black life” that they present. Obsessed with the Civil War, in which 600,000 people died in a conflict about the practice of slavery, Coates notes that “it had been glossed over in my education, and in popular culture, representations of the war and its reasons seemed obscured … as if … someone was trying to hide the books” (Ibid., 99). There is a way in which it seems, therefore, as if the Civil War never happened—and certainly when considering the situation of black lives today, that appears to be what Coates is forced to conclude. The heritage of destroying the black body, far from having ended with the Civil War, continues.

Coates’ references to the history of slavery and colonialism enable us to characterize the situation in the U.S. that he analyzes not only as a state of exception and more specifically a camp, but also as a necropolitical situation, to use Achille Mbembe’s productive notion (See: Mbembe 2003). Indeed, Mbembe focuses on those histories to develop the notion of necropolitics, which he situates closely—perhaps too closely–to the work of both Agamben and Michel Foucault. I say “perhaps too closely” for while Foucault in his work on power distinguishes between sovereignty as the power to take life or let live (the power of death) and biopolitics as the power to make life (to foster, generate, optimize it), Mbembe’s notion of necropolitics brings those two aspects of power together as one. Mbembe is compelled to make this deconstructive move due to the situations (and the particular histories) he is looking at, which include slavery and colonialism—both situations that neither Foucault nor Agamben pay much attention to. As scholars like Paul Gilroy (See: Gilroy 2010) or Alexander Weheliye (See: Weheliye 2014) have pointed out,[14] Foucault uses the term “colonialism” largely metaphorically; by characterizing the object of sovereign power as “bare” life, Agamben is incapable of thinking the importance of race in biopolitics. Both of those notions are important in Mbembe’s discourse, and this forces him to take up some distance from both Agamben and in particular Foucault, to whom he is nevertheless indebted. He does not share their euro-centrism, and this produces a shift in the theory. One way to summarize this would be that Mbembe, for his investigation of biopolitics, is operating from the position of those who die. He is interested in the “wounded or slain body” and how it is “inscribed in the order of power” (Mbembe 2003, 12).

On this last count, Mbembe considers two different inscriptions: the Hegelian one and that of Bataille. In Hegel, whose dialectical model Mbembe focuses on, the human being confronts death in negating nature by creating a world. It is through this exposure that the human being “truly becomes a subject” (Mbembe 2003, 14). To become a subject, then, “supposes upholding the work of death”, in the sense that life “assumes death and lives with it” (Ibid., 15). Death can thus become part of an “economy of absolute knowledge and meaning” (Ibid.). Negation drives the dialectic forward, but that forward movement is also the negation of the negation. There is death but it can productively become part of life.

Not so in Bataille, whose work Mbembe discusses in contrast: “Bataille firmly anchors death in the realm of absolute expenditure”, an expenditure that he calls “sovereign” (Mbembe 2003, 15). For Bataille, sovereignty thus breaks with the Hegelian dialectic, a break that is marked through its relation to death: “it is the refusal to accept the limits that the fear of death would have the subject respect” (Ibid., 16). The sovereign world, for Bataille, “is the world in which the limit of death is done away with” (Ibid.), as Mbembe quotes. Sovereignty therefore becomes a name for “the violation of all prohibitions” (Ibid.):

Politics, in this case, is not the forward dialectical movement of reason [as in Hegel]. Politics can only be traced as a spiral transgression, as that difference that disorients the very idea of the limit. More specifically, politics is the difference put into play by the violation of the taboo. (Ibid.)

But how does Bataille’s position relate to necropolitics?

In the opening paragraphs of his text, Mbembe distinguishes between what he appears to characterize as the violence of sovereignty and what he refers to as “the power of absolute negativity”. The latter he glosses with Arendt, and her claim that the concentration camps introduce us to a negativity of death that is outside of the life/death binary. Necropolitics, it seems, investigates such a negativity, the power of such absolute negativity, in the sense that it investigates the “camp” in which life—and in particular black life—is caught up. At the same time, however, necropolitics and the biopolitical sovereignty that it names are presented in Mbembe’s text along Hegelian lines, as conservative in the sense that they refer to “the generalized instrumentalization of human existence and the material destruction of human bodies and populations” (Mbembe 2003, 14). In other words, they refer to the way in which dead bodies can become part of an economy of knowledge and meaning.

I would characterize such an economy here based on the associations that Mbembe sets up as the economy of slavery and colonialism. But it is also the economy that Coates confronts in his close-reading of the death of black lives in the U.S. It is Mbembe who, in combination with Coates, enables us to mark this contemporary American situation as the situation of slavery and colonialism continued.

But Mbembe can arguably also show us, via Bataille, that such a Hegelian situation need not be the only one. There is also the absolute expenditure of death, which would not allow such instrumentalization of black death as part of the white people’s Dream. In other words, while Bataille appears to be associated with the absolute power of negativity that is in turn associated with the state of exception of the camp, there is also a way in which Bataille can become associated with another state of exception that would break with all of this.

Fanon, Once More

On this last count, Mbembe’s negotiation of Hegel and Bataille connects to Frantz Fanon, and the peculiar role of dialectics in his work. With Fanon, of course, there is no doubt: we are in the colonial situation, it is the colonial situation—the French presence in Algeria—that Fanon confronts. I am thinking in particular of the chapter from The Wretched of the Earth titled “Concerning Violence” (in the Constance Farrington translation)/ “On Violence” (in the Richard Philcox translation).[15] Born in Martinique, Fanon had studied psychiatry in France, and had been assigned to a hospital in Algeria. He quits his job there and joins the Front de Libération Nationale, the anti-colonial resistance fighters—as a Martiniquan/French citizen, not as an Algerian, not as Algeria’s colonial subject (even if he identified with the latter and ultimately became Algerian).[16] There is dialectics in Fanon’s text, but one feels that it is stuck in the basic opposition without synthesis: colonized confronts colonizer violently, but no progress, no compromise, no rational deliberation is possible (“Challenging the colonial world is not a rational confrontation of viewpoints”, he writes [Fanon 2004, 6]). Indeed, Fanon’s text is an affront to liberalism (Fanon writes about “the liberal intentions of the colonial authorities”, for example [Ibid., 30])—he rather snarkily attacks liberalism’s “gentleman’s agreement” (Ibid., 2) –and to the ways liberalism can be tied to colonialism to make history “move forward” (to evoke the Hegelian narrative).

Against this, Fanon asserts “absolute violence” (Fanon 1968, 37)[17]: the need to kick the colonizer out, and decolonize (which, as he notes, involves many levels of existence). It is a call “for total disorder” (Fanon 2004, 2),[18] “tabula rasa” (Ibid., 1). “[E]very obstacle encountered” must be “smash[ed]” (Ibid., 3). “[A]ny method which does not include violence” must be rejected (Ibid., 24). There is only one way to affirm that decolonization has been successful: do those who used to be the last now come first?[19] The point is to take the colonizer’s place (See: Ibid., 23). If that is not accomplished, nothing has been done.

It is true that there are moments in the text where the usefulness of violence also appears to be drawn into question, as when Fanon writes that “the question is not so much responding to violence with more violence but rather how to defuse the crisis” (Fanon 2004, 33).[20] Indeed, Mbembe has noted in Critique of Black Reason that “Fanon was conscious of the fact that, by choosing ‘counter-violence’, the colonized were opening the door to a disastrous reciprocity” (Mbembe 2017, 166). But the general orientation is unmistakable: violence is needed to end the madness. Absolute violence—non-dialectical violence. Tabula rasa. Absolute break. Cut. Out and out, as Philcox renders it (the translation is flawed, but its repetition of the “out” is useful here—it does render the outside-ness of ab-solute). Looking forward to Mbembe, this reads like Bataille’s absolute expenditure applied in the colonial context. In his reading of Fanon, Mbembe also recognizes that he proposes violence as the only way forward.

Nevertheless, it is not quite the only way. For it is crucial that the broader, constructive context in which, for Fanon, this destruction takes place is that of “national liberation, national reawakening, restoration of the nation to the people or Commonwealth” (Fanon 2004, 1). In short, it is that of… sovereignty. This is in many ways a remarkable point, and one can understand it, of course, in view of the fact that the colonized are, precisely, without their own nation-state. And it is certainly not as if Fanon was not aware of the problems of nationalist politics, of what he called “the pitfalls [mésaventures] of national consciousness”. But in this chapter he consciously leaves the portrayal of “the rise of a new nation, the establishment of a new state, its diplomatic relations and its economic and political orientation” (Ibid.) aside to focus on the violent break.[21] What will happen, however, when the absolute violence, the out and out violence for which he calls, is reined back in, is folded back into the national liberation that he calls for at the beginning of his text? What will happen when it becomes sovereign in that way again? Bataille of course calls his absolute expenditure sovereign in response to such a “conservative” folding within, precisely to attack the old sense of sovereignty. To an extent, those questions point to the problem of all revolutions, which ultimately fold their constituting power back into constituted power. How to run with constituting power appears to be the question. And more radically even: how to run with destituent power, apart from the constitutional gesture?

“National liberation.” Can we even think in those terms still, today? Could we call for a project of national liberation in response to the colonialism that the U.S., today, continues to practice on the black lives that live within its borders? We can think of the project of the Black Panthers, which involved a close study of law, and in some cases a rewriting of key documents of U.S. political history, as an attempt toward national liberation from colonialism and slavery. But within the limits of national sovereignty—at least for a brief while, before internationalism took over. An attempt to cleanse sovereignty from colonialism and slavery, to claim a sovereignty outside of the white people’s dream. Violence clearly has a role in this project. But what is its end? Is it an end? Is it pure means?

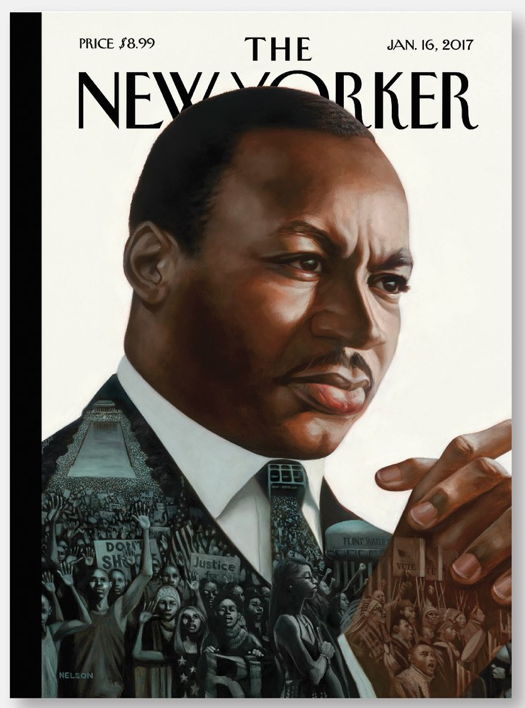

Consider in this context Kadir Nelson’s New Yorker cover “After Dr. King”, an alternative image of sovereignty: a black body of sovereign power that gathers within it the unhappy subjects who question the established sovereignty’s competency to protect them.

While it gives us an image of black sovereignty, it would be important to note that its central figure is that of Martin Luther King. Can the New Yorker cover be imagined with Malcolm X on it?[22] (Ta-Nehisi Coates notes Malcolm’s association with violence and his own dislike of it.) Or does the figure of King ultimately reconcile the violence of the subjects it carries within, and is Nelson’s image the ultimate Hegelian reconciliation of political violence and the avoidance of civil war? Would the Malcolm X cover have offended the New Yorker’s liberal sensibilities too much (the force of Bataille is certainly stronger in Malcolm than it was in King)? Does the King image continue, in that sense, the old sovereignty—plenty of similarities, after all, between Nelson’s image and the frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan—rather than bring the tabula rasa that Fanon calls for? And perhaps Fanon too, when he folds violence back into “national” liberation, ultimately does not live up to the radicality of his own position: complete rejection of the nation-state.

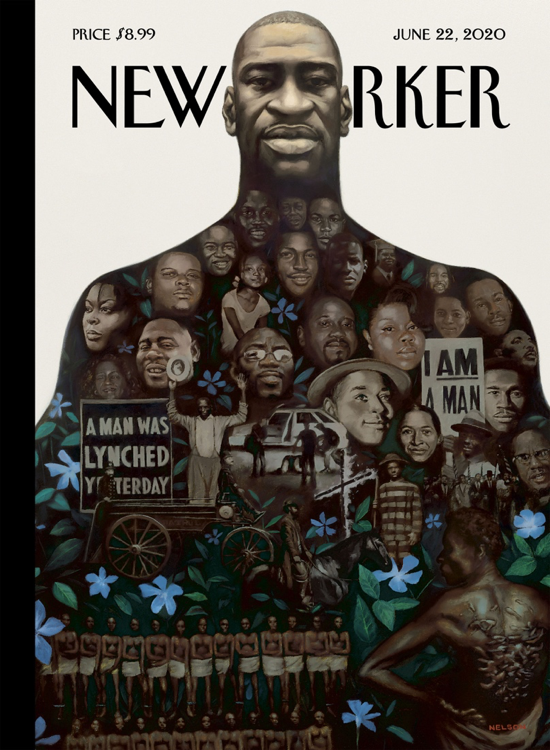

Nelson’s New Yorker cover “Say Their Names” can be seen as his most recent engagement with this problematic, this time in reference to George Floyd’s murder, and with Floyd embodying what Coates calls the U.S. “heritage” of violence against black bodies:

Such visual renderings of the problematic of sovereignty can be found elsewhere as well. Consider, for example, Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther (Disney, 2018), which problematically casts as its villain Killmonger, who wants to use the precious metal vibranium of King T’Challa’s Wakanda to liberate oppressed black people worldwide.

If I mention the Black Panther, it is partly because Coates has been involved in the comic book’s reimagining for the age of Black Lives Matter. The Black Panther poster, with the troubling tagline “Long Live the King,” clearly inscribes the film’s politics in the negotiations of sovereignty that I have opened up here.

When Fanon called for national liberation, however, he likely did not want “that old sovereignty” again. That might be the reason why, in his text, he also mentions “the creation of new men” (Fanon 2004, 2) as the result of the project of decolonization. Everything must start, he seems to say, from the creation of a new people, a new human being. It is from there that a new sovereignty might come along. This, among other things, enables David Macey to write in his biography of Fanon that “For Fanon, the nation is a product of the will, and a form of consciousness which is not to be defined in ethnic terms” (Macey 2012, 374). Mbembe focuses on Fanon’s notion of a new human being (rather than a new black man) in his book Critique of Black Reason. It is Fanon who, in Black Skin, White Masks, said that “Black” was “only a fiction” (Mbembe 2017, 159). “For him”, Mbembe notes, “the name referred not to a biological reality or skin color but to ‘one of the historical forms of the condition imposed on humans’” (Ibid.). Mbembe distinguishes Fanon’s position on this count from that of his teacher, Césaire, one of the key thinkers of “Négritude”. While Césaire as per Mbembe’s account is obviously no Senghor (the other thinker of negritude), Mbembe still presents him as more essentialist than Fanon, in the sense that he affirmed a negritude that Fanon ultimately[23] wanted to go beyond. Mbembe points out, however, that in Césaire’s “Black”, there was a universalism that was proposed, a universalism that could only emerge from “blackness” and the difference that it marks—a difference that reveals the world. For that revelation, blackness was essential. “But,” Mbembe asks, “how can we reread Césaire without Fanon” (who wrote after him)? For him, it is difficult, if not impossible.

This has everything to do with the notion of “critique” which names Mbembe’s project. As long as we are reading Césaire, we remain on the conservative side of critique, even if Césaire opens up the possibility of transgression. The transgression only arrives, however, with Fanon, who seeks to go beyond the notion of “Black” and imagines a world “freed from the burden of race” (a formula Mbembe repeats at least twice in his book—it closes the book as well [Mbembe 2017, 167, 183). “If there is one thing that will never die in Fanon”, Mbembe writes, “it is the project of the collective rise of humanity … Each human subject, each people, was to engage in a grand project of self-transformation, in a struggle to the death, without reserve. They had to take it on as their own. They could not delegate it to others” (Ibid., 162). The echoes here are multiple: struggle to the death—that’s Hegel, of course, the master-slave dialectic. But struggle without reserve: that’s Bataille’s absolute expenditure, the break with economy. Finally, the project of self-transformation: here we get echoes of the Enlightenment project and the “care of the self” that Foucault was so interested in toward the end of his life (the stuff that, according to some critics, made him vulnerable to neoliberalism [See: Zamora and Behrent, 2016]). It is no coincidence, I think, that the chapter I have been quoting from here is titled “The Clinic of the Subject”, which, in addition to echoing Fanon’s training as a psychiatrist, is also a very Foucaultian title.

So a number of questions emerge: at the level of subject formation, Mbembe seeks to present Fanon as more Bataille than Hegel.[24] But at the level of Fanon’s political project, this distinction—Hegel or Bataille—was undecided; it seemed that Fanon’s call for national liberation was perhaps more Hegel than Bataille. To be sure, if a national liberation is to be built around Bataille’s kind of subjectivity, then surely it will be very different from the old sovereignty and its dialectical transformation. We would get a break with dialectics here, that would bring about a truly new sovereignty rather than its dialectically accomplished next step. If this comes with the project of total self-transformation, the question remains how this would relate to the neoliberal, entrepreneurial subject. While Fanon of course could not foresee this question, Mbembe does address it in his introduction, where he presents neoliberalism as one of “three critical moments in the biography of the vertiginous assemblage that is Blackness and race” (Mbembe 2017, 2). Neoliberalism, defined as “a phase in the history of humanity dominated by the industries of Silicon Valley and digital technology” (Ibid., 3), has a “tendency to universalize the Black condition”, by which he means “practices [that] borrow as much from the slaving logic of capture and predation as from the colonial logic of occupation and extraction, as well as from the civil wars and raiding of earlier epochs” (Ibid., 4). It is a key component in what Mbembe calls “the Becoming Black of the world” (Ibid., 6). At no point does Mbembe discuss, however, how the language of self-transformation in Fanon could also become part of such a project.

There remains the third path that I alluded to in my introduction: the para-ontological understanding of blackness that would mark, next to both Hegel and Bataille, sovereignty’s continuous unsettling—its non-sovereignty, as I have suggested. Fred Moten has developed the notion of the para-ontological (after Nahum Chandler, and, by R.A. Judy’s account, Oskar Becker [Moten 2020]) in response to Western ontology which is, he argues, a “white” ontology that under the guise of universality refuses to think blackness. As he puts it in a lengthy, beautifully lyrical and intensely political article titled “Blackness and Nothingness (Mysticism in the Flesh)”:

[B]lackness is prior to ontology. … blackness is the anoriginal displacement of ontology … ontology’s anti- and ante-foundation, ontology’s underground, the irreparable disturbance of ontology’s time and space. (Moten 2013, 739)

Blackness—both in an identitarian way, as a condition that is particularly felt by black bodies, but also in a more general sense, as a structural condition that does not depend on one’s skin color (Moten distinguishes between “blackness and blacks” [Moten 2013, 749])—is precisely not covered by the ontological, and it is to move towards the philosophical thinking of blackness that Moten proposes his notion. The para-ontological, in such a project, captures what resides “next to” or “para” ontology. It captures the “nothingness” of blackness, the particular “nothingness”—which is evidently not nothing—that it marks. In my introduction, I have suggested reading this position politically, as a para-sovereign position

Moten turns in this context to Far Eastern thought and specifically the notion of “wu” (無, “nothing”). Moten brings this daoist notion of an active emptiness together with a black para-ontology and politics of resistance that can—in his view—be associated with Fanon (See: Moten 2013, 750). The thought of the dao, and specifically of “wu”, is a thought that puts being on hold rather than “in the hold” (Ibid.) as Moten’s reference to the slave-ship has it. Yet it is also through its attention to “the hold” that black studies (as Moten sees it) “disrupts” (Ibid., 751) the “nothingness” of Far Eastern thought, forcing “‘the real presence’ of blackness” (Ibid.) back into it and working both with and against the suspension that “wu” brings. There is, clearly, something to be learned from and resisted within the para-ontological. In the words of Abdelkebir Khatibi, another thinker of the dao, what’s needed here is a “double critique” (Khatibi 1983, 12), both of the para-ontological (as subject genitive: the para-ontological suspends, in the way that “wu” suspends) and of the para-ontological (as object genitive: the para-ontological is suspended by “‘the real presence’ of blackness”).

Moten’s choice (after Chandler) for and understanding of the preposition “para” or “next to” is worth pausing over in the context of my discussion of sovereignty, because it marks a moving sideways rather than up or down or inside or out. If up/down or in/out can easily be appropriated within the dialectical (Hegelian) and transgressive (Bataillean) models of sovereignty that I previously found in Mbembe, this is more difficult to do with the horizontal dynamic of the next to, which posits itself on the same plane as whatever it pre-poses. But does this lateral unsettling take us out of sovereignty? It seems that even in the intervention of such a sideways move, the para maintains a hyphenation to the ontological, some kind of connection—that of a mere dash—to what it unsettles. Read politically, this would also apply, then, to the para-ontological approach to sovereignty, in which some connection to sovereignty would be maintained by the mere presence of a dash. There is always the temptation of overlooking this dash, and rewriting this continuous unsettling as an outside—more radical than Bataille’s, which still calls itself sovereign. Moten in fact flirts with such an outside. “On the one hand”, he writes, “blackness and ontology are unavailable to each other” (Moten 2013, 749)—and the project of para-ontology seeks to remedy that situation. “On the other hand”, he continues, “blackness must free itself from ontological expectation, must refuse subjection to ontology’s sanction against the very idea of black subjectivity” (Ibid.). The more radical conclusion, then—following the invitation of this “other hand”–would simply be to reject ontology altogether, a rejection that would lead to non-sovereignty. But Moten might consider such a conclusion irresponsible from the point of view of a history in which whiteness and blackness have been co-constituted in ontology, through ontology, and in/through sovereignty. In other words: while blackness might desire the outside, it may not be afforded such luxury from the point of history. Indeed, none of us may.

Critique and Indigenous Politics

“If we owe Fanon a debt,” Mbembe writes, it is for the idea that in every human subject there is something indomitable and fundamentally intangible that no domination—no matter what form it takes—can eliminate, contain, or suppress, at least not completely. Fanon tried to grasp how this could be reanimated and brought back to life in a colonial context that in truth is different from ours, even if its double—institutional racism—remains our own beast. For this reason, his work presents a kind of fibrous lignite, a weapon of steel, for the oppressed in the world today. (Mbembe 2017, 170)

It is worth noting, in the context of a discussion of sovereignty, the potential complicity of such a discourse with exceptionalism, and some of the problems this raises. This becomes clear in Mbembe’s book. When, a few pages later, Mbembe turns to the politics of art in this context, he writes:

Here the primary function of the work of art has never been to represent, illustrate, or narrate reality. It has always been in its nature simultaneously to confuse and mimic original forms and appearances. … But at the same time it constantly redoubled the original object, deforming it, distancing itself from it, and most of all conjuring with it. … In this way the time of a work of art is the moment when daily life is liberated from the accepted rules and is devoid of both obstacles and guilt. (Ibid., 173)

I can follow this final passage all the way up to its last sentence. But I do not think its grand, concluding statement—liberation from accepted rules, being devoid of obstacles and guilt—follows logically, or evokes the same politics, as the language of constantly redoubling, deforming, and distancing that Mbembe uses earlier on. I am concerned about how the final line promotes an exceptionalism—“liberation from the accepted rules”, “devoid of both obstacles and guilt”–that the previous language actually dismantles. I like the dismantling better. It marks an immanent criticism of sovereignty that may be more efficient, politically, at dismantling sovereign exceptions than Mbembe’s final sentence.

Given this conclusion, however, one should not be surprised by the final paragraph of the chapter: to be African, it proclaims, is to be “a man free from everything, and therefore able to invent himself. A true politics of identity consists on constantly nourishing, fulfilling, and refulfilling the capacity for self-invention. Afro-centrism is a hypostatic variant of the desire of those of African origin to need only to justify themselves to themselves” (Mbembe 2017, 178). Mbembe prefers here a world that is constituted by the relation to the Other—and it is the human that introduces that otherness into blackness, which he argues must be “clouded” (Ibid., 173). This will be the beginning—via Fanon—of the “post-Césairian era” (Ibid.). Again, one wonders whether “clouding”—a term he uses earlier in the chapter—can mean the same as “free from everything”; one wonders whether “post” can really refer to the radical break that seems to be alluded to here. Ultimately, Mbembe’s critique appears to be torn between a more conservative articulation that would remain within the critique’s limits, and a more radical one that would seek to transgress it. Given that he relies for his critique largely on Fanon, this should come as no surprise, as I have shown that Fanon himself, too, is caught up within this tension of staying within (Hegel) and going beyond (Bataille). Everything in “On Violence” points to the beyond; and yet, the constructive part of its project—not addressed in the chapter—takes place “within” national liberation. Ultimately, what haunts the difference between those two positions is the problematic of sovereignty itself: of its paradoxical association both with an outside and a within (“I who am outside of the law, declare that there is nothing outside of the law”, as Agamben captures the paradox of sovereignty). And, of course, of an even greater sovereignty—absolute violence, absolute expenditure—that, as the sovereignty of sovereignties, may ultimately do no more than perpetuate sovereignty’s exceptionalism. The third path, as I’ve also suggested, would be that of non-sovereignty.

Indeed, it may be that for black life, the project of sovereignty is over, that Fanon’s call for national liberation and the inspiration if provided for the Black Panther Party are a thing of the past, for good. Joan Cocks, focusing on the Israel/Palestine situation and Indigenous politics, has laid out some very good reasons for this (See: Cocks 2014). But if that is so—if sovereignty should indeed be seen as a thing of the past–it seems crucial at a time when sovereignty is going through a revival on the Right, in open conflict with the “horizontalist” Black Lives Matter movement today, that new forms of collective organization are proposed against sovereignty. Are those non-sovereign forms of collective organization? Do they claim sovereignty otherwise? How do they effectuate their power?

It is interesting to compare historical narratives of sovereignty as they are presented in different disciplines. In political theory, studies of sovereignty usually tell the story of sovereignty’s decline after WWII due to transnational political developments such as European integration or human rights politics. In Indigenous Studies, however, scholars tend to note that “following World War II, sovereignty emerged not as a new but as a particularly valued term within indigenous discourses to signify a multiplicity of legal and social rights to political, economic, and cultural self-determination” (Barker 2005, 1). Precisely when the term is on the wane in the West, where it was born, it is on the rise as an emancipatory tool for example for those communities “within” the West that seek to contest their subjection to another sovereign power. Those communities turned toward the term sovereignty, as Joanne Barker explains, in part to refuse the label “minority group”: “Instead, sovereignty defined indigenous peoples with concrete rights to self-determination, territorial integrity, and cultural autonomy under international customary law” (Barker 2005, 18). Of course, while refusing the label “minority group”, the communities instead adopt the term “sovereignty”, which was born and shaped in Europe. There may be a deeper problem here, as scholars like Elizabeth Povinelli have noted (See: Povinelli 2002), with the (Hegelian) politics of “recognition” (“Anerkennung”, in Hegel’s celebrated master/slave-dialectic) and how it tends to confirm the master’s terms. Indeed, it might seem strange to use the term “sovereignty” both to refer to the camp-like situation of black life in the U.S as exposed by Coates,[25] and now for these Indigenous struggles for self-determination. But such strangeness marks what Barker characterizes as the “contingency” of sovereignty, the fact that “[t]here is no fixed meaning for what sovereignty is—what it means by definition, what it implies in public debate, or how it has been conceptualized in international, national, or indigenous law” (Barker 2005, 21). The passage is worth quoting in full:

Sovereignty—and its related histories, perspectives, and identities—is embedded within specific social relations in which it is invoked, and given meaning. How and when it emerges and functions are determined by the “located” political agendas and cultural perspectives of those who rearticulate it into public debate or political document to do a specific work of opposition, invitation, or accommodation. It is no more possible to stabilize what sovereignty means and how it matters to those who invoke it than it is to forget the historical and cultural embeddedness of indigenous peoples’ multiple and contradictory political perspectives and agendas for empowerment, decolonization, and social justice. (Ibid.)

Sovereignty is, as I have indicated elsewhere (See: Boever 2016), plastic and it is this plasticity that any critique of sovereignty needs to assess. This is also to say that sovereignty is not sovereign—a claim that should be distinguished from the call for non-sovereignty.

If indigenous sovereignty thus emerges as a kind of serious playground or site of experimentation to think through new democratic possibilities today, it is precisely because it enables an immanent critique of sovereignty, as a politics of sovereignty that can only be critical. This is so, as Barker points out in her introduction to the book Critically Sovereign, for two reasons: on the one hand, because native sovereignty relates critically to the sovereignty of the nation-state, as a sovereignty that contests the power of another; second, because native sovereignty itself suffers from many of the same problems as the sovereignty of the nation-state, and therefore some of the criticisms that have been levelled against the sovereignty of the nation-state also apply to native sovereignty. In essence, this criticality revolves around the fact that when it comes to the indigenous politics of sovereignty, one can distinguish between two kinds: that which takes place “in relation to the state” and that which takes place “within the state” (Barker 2017, 8). Whereas the former relates to native sovereignty’s relation to the sovereignty of the nation-state, the latter operates within the sovereignty of the nation-state, and to participate in the latter can be—and has been—perceived as participating in the imperial and colonial politics of oppression of the sovereign nation-state. This is why what Barker refers to as “Civil Rights politics” does not cover the relation between indigeneity and sovereignty. It only covers the politics “within the state” part of the relation. In addition, one should also consider indigenous sovereignty’s relation to the sovereignty of the nation-state and the tensions it lays bare.

Barker articulates this (as well as other key parts of the critical sovereignty she develops) through a focus on “gender, sexuality, feminism” within her exploration of native sovereignty. She points out, for example, how the call for “women’s and gay’s liberation and civil rights equality … has been narrated as racializing and classing gender and sexuality in such a way as to further a liberal humanist normalization of ‘compulsory heterosexuality’, male dominance, and white privilege” (Barker 2017, 12). In other words, there is a subject-formation that is operative in such liberation struggles, and while this does not cover the full story of those struggles, this is an important aspect of them that should be drawn out. Any hegemonic formation, in the terms developed by Chantal Mouffe and Ernesto Laclau, will produce a counter-hegemonic formation; any rendering legible produces illegibility as Barker (via Judith Butler) puts it—there are always traces of internal exclusion or exception. It is from those traces—from those frictions, if you will–that politics develops. Indigenous approaches to for example gender and sexuality can be interesting in this context because they can “defy binary logics and analyses” (Ibid., 13)—and those include, it should be pointed out, discourses of a “third” (which ultimately in their very attempt to posit a third appear to confirm a pre-existing binary). The point of Barker’s approach appears to be to “defamiliarize gender, sexuality, and feminist studies to unpack the constructedness of gender and sexuality and problematize feminist theory and method within Indigenous contexts” (Ibid., 14). Indigenous politics are interesting in this context as well because when for example indigenous women seek to pursue a feminist politics to redress their own status in their communities, they run into resistance because their tribe members perceive them to be sleeping with the enemy—to be “non- or anti-Indigenous sovereignty within their communities” (Ibid., 20). “They accused the women of being complicit with a long history of colonization and racism that imposed, often violently, non-Indian principles and institutions on Indigenous people” (Ibid.). So gender, sexuality, and feminism have a difficult place within native sovereignties, and it is precisely around the notion of sovereignty that this difficulty gets played out.

Barker’s introduction also contains hope for the future, though. Such hope articulates itself around a poetic project of remaking—of remaking masculinity for example; but also of remaking the world. This is about asserting a sovereignty that would not fall into the old traps of sovereignty—that would not reify, for example, “heterosexist ideologies that serve conditions of imperial-colonial oppression” (Barker 2017, 24). It would be a remaking that might confront “the social realities of heterosexism and homophobia” within indigenous communities (Ibid., 25). In other words, “Indigenous manhood and masculinity [need to be redefined] in a society predicated on the violent oppression and exploitation of Indigenous women and girls and the racially motivated dispossession and genocide of Indigenous peoples” (Ibid., 26). It is precisely here, in the project of not opposing the violent sovereignty of the oppressor with a call for a violent sovereignty of the oppressed—with the Fanonian attempt to go beyond such a dialectical opposition—that the possibility of an Indigenous future opens up, an Indigenous Futurism (of sovereignty). It is because of the very particular position that Indigenous sovereignty is in that this becomes possible. And this is the reason, I think, why so many contemporary theorists of sovereignty turn to this example to pursue a redefined politics of sovereignty today. The turn towards indigenous sovereignty enables, precisely, what Barker labels a “critical” sovereignty. It enables what one could, more precisely, call a “critique” of sovereignty where the power we call sovereign is not abandoned, not rejected, but transgressively transformed from within in view of the abuses it has enabled and the possibilities for emancipation it has opened up.

Now, the situations of African-American life and Native American life in the U.S. are of course not the same, as scholars have pointed out; African Americans and Native Americans have been governed in different ways, through different strategies and with different purposes. Their histories are connected in complicated ways. Nevertheless, it seems that when it comes to the issue of sovereignty, and to the debates between those who propose to reject it and those who pragmatically adopt it (in some cases to resist being labelled a “minority group”), an alliance between African-American and Native American thinking about sovereignty may be fruitful. It may lead to a situation where the exceptionalism that tends to get a negative rap opens up to democratic possibilities, as Bonnie Honig has considered in her work (See: Honig 2011), and counter-sovereignties are developed (as Honig has proposed in her book on Antigone [See: Honig 2013]). When it comes to actively taking on those sovereignties on the Right that are finding new life today, such democratic re-elaborations of sovereignty may be the most effective—at least until other, better options come along to defeat fascism.

Arne De Boever teaches American Studies in the School of Critical Studies and the MA Aesthetics and Politics program at the California Institute of the Arts (USA). He is the author of States of Exception in the Contemporary Novel (Continuum, 2012), Narrative Care (Bloomsbury, 2013), Plastic Sovereignties (Edinburgh University Press, 2016), Finance Fictions (Fordham University Press, 2018), and Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism (Minnesota University Press, 2019). His book François Jullien’s Unexceptional Thought: A Critical Introduction is forthcoming with Rowman & Littlefield (2020).

References

Agamben, Giorgio (2015) Stasis: Civil War as a Political Paradigm (Homo Sacer II, 2). Trans. Nicholas Heron. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Alexander, Michelle (2012) The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Color Blindness. New York: The New Press.

Barker, Joanne (2005) “For Whom Sovereignty Matters.” In: Barker, Joanne, ed. Sovereignty Matters: Locations of Contestation and Possibility in Indigenous Struggles for Self-Determination. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Barker, Joanne, ed. (2017) Critically Sovereign: Indigenous Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bidet, Jacques (2016) Foucault With Marx. Trans. Steven Corcoran. London: Zed Books.

Biebricher, Thomas (2014) “Sovereignty, Norms, and Exception in Neoliberalism”. Qui Parle 23:1, 77-10.

Boever, Arne De (2009) “Agamben and Marx: Sovereignty, Governmentality, Economy.” Law & Critique 20:3, 259-270.

— (2016) Plastic Sovereignties: Agamben and the Politics of Aesthetics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Coates, Ta-Nehisi (2015) Between the World and Me. New York: Spiegel and Grau.

Cocks, Joan (2014) Sovereignty and Other Political Delusions. New York: Bloomsbury.

Cooper, Melinda (2004) “Insecure Times, Tough Decisions: The Nomos of Neoliberalism”. Alternatives 29: 515-533.

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari (1987) A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Elden, Stuart (2016) Foucault’s Last Decade. Cambridge: Polity.

Fanon, Frantz (1968) “Concerning Violence”. Trans. Constance Farrington. In: Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove.

—. “On Violence” (2004) Trans. Richard Philcox. In: Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove.

—. “De la violence” (2002) In: Fanon, Les damnés de la terre. Paris: La découverte.

Foucault, Michel (2003) “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the Collège de France 1975-1976. Trans. David Macey. Ed. Mauro Bertani and Alessandro Fontana. New York: Picador.

Gibson, Nigel. “Relative Opacity: A New Translation of Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth—Mission Betrayed or Fulfilled?” (2007) Social Identities: Journal for the Study of Race, Nation and Culture. 13:1, 69-95.

Gilroy, Paul (2010) Darker Than Blue: On the Moral Economies of Black Atlantic Culture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Haraway, Donna (2008) When Species Meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hobbes, Thomas (1998) Leviathan. New York: Oxford University Press.

Honig, Bonnie (2011) Emergency Politics: Paradox, Law, Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

— (2013) Antigone, Interrupted. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kantorowicz, Ernst (2016) The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kalyvas, Andreas (1999-2000) “Carl Schmitt and the Three Moments of Democracy”. Cardozo Law Review 21: 1525, 1525-1565.

Khatibi, Abdelkebir (1983) Maghreb Pluriel. Paris Denoël.

Macey, David. Frantz Fanon: A Biography. New York: Verso, 2012.

Marriott, David (2016) “Judging Fanon”. Rhizomes 29, accessible: http://www.rhizomes.net/issue29/marriott.html.

Mbembe, Achille (2003) “Necropolitics”. Trans. Libby Meintjes. Public Culture 15:1, 11-40.

—. Critique of Black Reason (2017). Trans. Laurent Dubois. Durham: Duke University Press.

Mirowski, Philip (2014) Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown. New York: Verso.

Moten, Fred (2013) “Blackness and Nothingness (Mysticism in the Flesh)”. South Atlantic Quarterly 112:4, 737-780.

—. (2020) “Of Human Flesh: An Interview with R.A. Judy” (Part Two). boundary 2 online 05/06/2020, accessible: https://www.boundary2.org/2020/05/of-human-flesh-an-interview-with-r-a-judy-by-fred-moten/.

Mouffe, Chantal, ed. (1999) The Challenge of Carl Schmitt. New York: Verso.

Povinelli, Elizabeth (2002) The Cunning of Recognition: Indigenous Alterities and the Making of Australian Multiculturalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

Scheuerman, William (1997) “The Unholy Alliance of Carl Schmitt and Friedrich A. Hayek”. Constellations 4:2, 172-188.

Sturm, Circe (2017) “Reflections on the Anthropology of Sovereignty and Settler Colonialism: Lessons from Native North America”. Cultural Anthropology 32:3, 340-348.

Thomas, Brady Heiner (2007) “Foucault and the Black Panthers”. City 11:3, 313-356.

Weheliye, Alexander G. (2014) Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human. Durham: Duke University Press.

Young, Robert (2001) Postcolonialism: A Historical Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.

Zamora, Daniel and Michael Behrent, eds. (2016) Foucault and Neoliberalism. Cambridge: Polity.

[1] I would like to thank Sarah Brouillette and in particular Olivia C. Harrison, AdouMaliq Simone, and Ryan Bishop for their helpful feedback on earlier versions of this article.

[2] Donna Haraway would ask us to consider to what extent this Hobbesian claim is based on the observation of how actual wolves live together (Haraway 2008).

[3] The king has two bodies: an earthly, biological one and a spiritual, symbolic one. This image shows the king’s symbolic body. It is because of this two-body problematic that we have the acclamation, “The king is dead, long live the king!”—the biological king is dead, long live the symbolic body of the king, which is immortal. There is barely a pause between the two parts of the acclamation to ensure the continuity of power. See: Kantorowicz, 2016.

[4] See: Agamben, 2015.

[5] Foucault, “Society”, 90.

[6] Ibid., 90.

[7] The validity of this “against” may have to be contested. That certainly appears to be Agamben’s project, against Foucault, in: Agamben, Stasis. He presents Hobbes there as a thinker of the dissolved multitude of civil war rather than as a theorist of the people. So rather than being a theorist of peace, Hobbes is a theorist of civil war. Following Agamben, one would have to conclude that Foucault blames Hobbes for a position that is not his.

[8] Andreas Kalyvas’s reading of Schmitt’s Constitutional Theory—in many ways an aberrant work in Schmitt’s oeuvre—also begs us to differ: Kalyvas 1999-2000.

[9] Ibid., 108.

[10] I would like to thank AbouMaliq Simone for reminding me of this third path. I take the phrase “continuous unsettling” from his generous comments on my article, which drew my attention to: Marriott 2016.

[11] It seems, rather, that today exceptionalist sovereignty and neoliberalism need to be thought together: Scheuerman 1997; Biebricher 2014; Mirowski 2014.

[12] To be clear, I would not want to suggest here that the European frame of reference, in particular the reference to Auschwitz, is somehow needed to draw out the gravity of the situation of black lives in the U.S. Certainly when “camp” is used as the paradigm to capture the specific historical situation of black lives in the U.S., the specificity of that situation and the localization of the notion of camp that it requires would need to acknowledged. Ava DuVernay’s documentary film 13th (Kandoo Films/Netflix, 2016) does some of that work, relying in part on: Alexander 2012.

[13] This something partly gets a geographical name in Coates’ book: Paris. It is in Paris where Coates realizes that there are places where he is not other people’s problem. Black people are not the problem of Paris; one should add that that dubious privilege is reserved for the Arabs, though Coates does not state this explicitly. In his turning to Paris as refuge, Coates is of course not alone: James Baldwin, Richard Wright, William Gardner Smith, and others, had done the same before him.

[14] Weheliye 2014, 56 and further. To be clear, Gilroy points to the usefulness of the camp to analyze the situation of black lives in the U.S., but also emphasizes Agamben’s blindness to race.

[15] I will refer here to two English translations of Fanon’s text: Fanon 1968 and Philcox 2004. For the French original, see Fanon 2002.

[16] There is an affiliation across colonial situations that, in view of discussions of Fanon’s work such as Robert Young’s (Young 2001), needs to be acknowledged here: the “I” of the native in Fanon’s text cannot straightforwardly be identified with Fanon himself, as in Algeria he was not a native or “indigène”, a term that Philcox unfortunately renders as “colonial subject” (Fanon 2004, 15). Fanon arrived in Algeria as a French citizen, which as a Martiniquan he had become after 1946, when Martinique became a “department” of the French state.

[17] This is the Farrington translation. Fanon’s original French has “violence absolue” (Fanon 2002, 41). Philcox renders this as “out and out violence” (Fanon 2004, 3).

[18] Farrington renders this as “complete disorder” (Fanon 1968, 36). The original French has “désordre absolu” (Fanon 2002, 39).

[19] When Fanon offers this line, he is referencing the New Testament, which casts the decolonized community he imagines in “messianic” terms. This is so even if he compares Christianity to DDT earlier on in his text.

[20] Farrington’s rendering is more correct: “the question is not always to reply to it by greater violence, but rather to see how to relax the tension” (Fanon 1968, 73). Here is Fanon: “la question n’est pas toujours d’y répondre par une plus grande violence mais plutôt de voir comment désamorcer la crise” (Fanon 2002, 72).

[21] Nigel Gibson gets this negotiation exactly right in the context of a discussion of dialectics: Gibson 2007.

[22] Nelson in fact did another cover for The New Yorker that had Malcolm X on it, but he appeared there as part of a group of African-American figures at the center of which was the (much more acceptable) figure of James Baldwin. The other cover can be accessed at: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/cover-story-2017-01-16.

[23] David Macey observes that around 1961, “Fanon had reached, or perhaps returned to, the Sartrean position of which he had been so critical in Peau noire, masques blancs [Black Skin, White Masks]: negritude had been no more than a ‘racist anti-racism’ that had to be transcended. Negritude could exist only in the context of white domination” (Macey 2012: 372).

[24] The exact relation of this position to Foucault is complicated and will have to be discussed on another occasion.

[25] I should note that while Agamben himself has paid no attention to Indigenous politics, his work has proved quite productive in Indigenous Studies. As Circe Sturm observes, “For scholars working in Native North America, settler-colonial theory becomes especially productive when placed in conversation with Giorgio Agamben’s ideas on state sovereignty” (Sturm 2017, 342).