This essay has been peer-reviewed by “Frictionless Sovereignty” special issue editor (Ryan Bishop), and the b2o: An Online Journal editorial board.

“… the West has never been further from being able to live a true humanism – a humanism made to the measure of the world.” (Césaire 1955: 73)

This article is the abstracted result of my having witnessed the racialized infrastructures of European bordering practices in an apparent frictionless sovereign territory: the Schengen area. Embodying whiteness and holding European Union passport privilege in this context and situation, I was allowed to witness these events without any real danger to my person. I am hoping to remain cautious, however, of how my privileged position might be doubled in writing. An academic reflection could become a parasitical tool and an appropriative parsing of a traumatic experience that does not belong to me. I will therefore not engage in detailing the experience or what it has produced for those involved. I will, however, briefly recount some of the acts of policing I witnessed and how they constituted borders for some bodies where no borders exist for others.[1]

In the middle of the night in May 2019, Austrian police took a woman and her two children off a train, leaving them in the train station of Villach, 20 kilometers before the border with Italy. The Austrian train inspectors and the police officers took this action on valid ticket holders and refused them re-entry into Italy on the basis of them not having European passports. The family was, however, holding valid travel documents issued by Italy, which should have granted them access across the Schengen space of Austria (under the 1951 Refugee Convention) and moreover a return to the issuing country. Instead, after being taken off the train, they were “advised” to seek the local Austrian asylum seekers’ centre, risking refusal and possibly detention. An attempt to board the next train to Italy many hours later was met with direct obstruction by two Italian Carabinieri (dispatched to this site in Austria) and two local Austrian police officers, alongside train employees. As holders of valid travel documents, the family was able to eventually return to Italy by bus (however, not on the main Austrian lines but an adjacent low-cost one).

My aim in this article, starting from the events I have just recounted, is to reflect on the current Schengen area at the peak of anti-immigration law-making, and on the racial infrastructure underpinning Schengen territories and their governance. I argue that the existence and application of Schengen Border Codes articulates states of exception in the already racialized assemblages of European regulating and policing, making visible the friction in the promises of frictionless sovereignty of the Schengen Area and turning (some) bodies into borders. I do this work with the support of brilliant black scholars who have taken up similar questions, worked extensively on them and have produced critical responses to excessively cited white European scholarship in this area. Specifically, I will approach these issues through Alexander Weheliye’s deployment of habeas viscus—having flesh–and his emphasis on black feminist theory’s contribution to the revision of conceptions of the human that stem from “the world of Man” (via Sylvia Wynter) and liberal modern humanism. By Man, Weheliye means the configuration of the heteromasculine, white, propertied, liberal subject produced from a type of surplus of the human, through exploitation which renders anyone outside of this formation as “exploitable nonhumans, literal legal no-bodies” (2014a: 135). I aim to show how Europe is bound to Man’s legal apparatus and how Man’s juridical machine articulates itself in embodied bordering practices, even in non-border sites and in areas where movement should be frictionless, given the Schengen Agreement.

These instances of border policing have often been approached in academic reflections via the work of Michel Foucault and Giorgio Agamben. About these writers, who are all too frequently cited in work about biopolitics and population control, as well as about bare life, law and power respectively, Weheliye states that their disavowal from engagement with black studies and the black struggles of their times is what makes their concepts “transportable to a variety of spatio-temporal contexts” (2014a: 6). Their lack of consideration of an explicitly racialized viewpoint, available and expressed by various authors like Frantz Fanon, Nahum Chandler, or Sylvia Wynter, gives Foucault and Agamben’s concepts a “veneer of universalism”. In the case of Foucault in particular, Weheliye brings to our attention that he chose not to engage with the knowledge on race and power produced by the Black Panther Party through its struggle in the prison abolition movement, and did not seriously respond to the work of U.S. black feminist activists like Angela Davis. This cannot be anything but a stubborn omission, given Foucault’s involvement with the prison abolition movement in France and in Algiers (Weheliye, 2014a: 62-63). Other authors have read this and other Foucauldian omissions as non-engagement with efforts towards dismantling the white, male epistemic subject (Rodríguez). In the case of Agamben, Weheliye engages in a thorough critique, detailing how the former’s constant universalizing of the state of exception and seeing “bare life and the state of exception as exclusively legal categories” (Weheliye: 83) undermines the possibility of a situated, embodied conception of the flesh. The point regarding both these authors remains plainly that “their major theoretical formulations were developed often in distinction or without recourse to the long histories of globalised racial power” as Dhanveer Singh Brar sharply notes in a review of Weheliye’s book (Brar 2014: 145).

In contrast, for Weheliye, habeas viscus posits “one modality of imagining the relational ontological totality of the human” (Weheliye: 4) in a given spatiotemporal context, a situated configuration that manifests in a determinate present, not a messianic tomorrow. I follow this Weheliyan route rather than the abundant Agambenian and Foucauldian interpretations produced in studies on anti-immigration law-making in Europe, as it produces a much more grounded position on what having flesh and having a body means as perpetual exception in the always already racialized assemblages of legal frameworks and policing powers, applied in this case to spaces of transit within the Schengen territories.

Furthermore, I will centre the discussion on how these racialized assemblages open up, once more, questions of being human. Weheliye critiques the notion of the human which emerged with white colonial thought, extends to the continued omissions and universalising which happens in French theory, and continues to white feminist critical thought, such as the influential work of Judith Butler in gender studies, violence, and law. He points out that these theories, like most of post-1960s critical thought do not engage seriously and attentively with the work of contemporaneous black authors, such as Aimé Césaire, who cautioned about the double danger of including black subjects in the universalising category of Man or their relegation to the particulars of ethnography, something that writers like Hortense Spillers, Sylvia Wynter and Saidiya Hartman expand upon and continue to explore in readings of documents and histories of black lived experience. Weheliye also calls forth some of the theoretical propositions of new materialism and certain posthumanist incarnations for comparatively summoning chattel slavery and black experience of that historical period to set up legal structures for animal rights. In the cases where the engagement is not simply superficial or tokenistic, Weheliye states, the question of racialization in relation to the notion of the human is another form in which “black subjects […] must bear the burden of representing the final frontier of speciesism” (2014a: 11).

On the specifics of how crossing lines and making frontiers and comparative processes meet, he continues:

Comparativity frequently serves as a shibboleth that allows minoritized groups to gain recognition (and privileges, rights etc.) from hegemonic powers (through the law, for instance) who, as a general rule, only grant a certain number of exceptions access to the spheres of full humanity, sentience, citizenship, and so on. (Weheliye 2014a: 13)

Thus, following this call against a larger “grammar of comparison”, which brings with it a jargon of tabulation, measuring and calculability of black suffering, I will focus on the ways in which current European Union immigration law and its promises of frictionless sovereignty in fact open up the racialized foundations of European law-making and the frictions made visible by the passing of bodies over borders. The roots of anti-black racism in legal structures and the ways in which academic knowledge has made anti-blackness into a universal thought currency is what allows for the questions Weheliye raises to be asked of the European context. The bodies are the borders, seeking not exceptional recognition as human, but always already holding full expression and power to show the law as a racialized assemblage and the Schengen area in which this takes place as a prime instantiation of racialized infrastructure at work.

The Rule of Exception: A Question of the Human

“The universalization of exception disables thinking humanity creatively.” (Weheliye 2014a: 11)

European states ruled by right majority governments, with leaders like Italy’s former Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of the Interior Matteo Salvini, have set the precedent of threatening to cease the implementation of the Schengen Agreement, aiming to stop free movement across intra-Schengen borders (the so-called Salvini Decree abolished the issuing of residence permits on humanitarian reasons). Such suspension can only be done in exceptional cases, the conditions for which had not been met at the point of this request as far as the European Trade Union Confederation was concerned. Thus, the friction at the border between Schengen member states has been enacted through legally vague states of exception, not declared as such but in fact existing through the instantiation of added codes and emergency provisions, on the bodies of those crossing. Sites where bodies as borders are made visible in current racialized assemblages are often infrastructural nodes, like train stations and bus depots, as has been my first hand experience in the border town of Villach in Austria. Fully embedded in capitalist infrastructure, in circuits and flows, these spaces have become more and more spaces of incarceration and deportation, alongside other forms of violence and abuse. This is not a new situation across Europe of the last five years. As a temporary prison or camp, like in the case of Budapest’s Keleti, the train station has also acted as centre-piece for legitimizing an illusion of alignment for Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s rule with his political agenda. Additionally, Brussels’s Central Station has been portrayed as the fear-mongering site at the “heart of Europe,” which right-wing media often uses as its visual trope for a refugee “take-over”.

Major European train stations are not the focus of this article but instead I will attend to a particular intra-Schengen border policing that currently happens between Austria and Italy, as witnessed in a rail station in the small town of Villach, one of the last Austrian stops before crossing into Northern Italy. Small nodes like this, under-observed by non—governmental organisations and activists due to reduced capacity are sites that can offer some understanding about how EU Law and its exceptions are made visible as racialized assemblages. Yet more importantly, what was made apparent in this case was not how the rule of exception functions on site but the “hieroglyphs of flesh” (Weheliye) onto which historical and current scales of colonialism and border crossing meet, as racialized assemblages and infrastructures. I expand upon these issues in section two.

In what follows, I will take up Alexander Weheliye’s critique of Agamben’s “state of exception” (1998) as temporally bound, to argue for the former’s proposition that “exception” is yet another instantiation of what he identifies as racialized populations “suspended in a perpetual state of emergency” (Weheliye: 2014a). Mirroring that thought, I claim in this article that my observation from witnessing policing of borders outside of border points themselves can be seen as an insight into how the entirety of the legal framework of the EU project can come under scrutiny. Such a route resists thinking this one instance as a state of exception, as the legal framework of Schengen law-making sets it up to be.

Countries like Italy and Austria, both holding their respective fascist pasts, currently right-wing party ruled[2] and sharing a border, have been making their own provisions, emergencies, exceptions and threats based on a particular set of codes added to the Schengen Agreement and EU Law and entitled the Schengen Border Codes.[3]

As the “Asylum Information Database”[1] (2018) built by the European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE) states:

Notwithstanding that the issue of refugees’ access to the territory has traditionally been associated with the external borders of the EU (and therefore a handful of countries), the reintroduction of internal border controls in the Schengen area in the last three years has resulted in border control becoming a regular activity throughout the continent. The intra-Schengen dimension of the debate, and practice in countries such as France, Austria, Sweden or Germany, remain highly pertinent in the light of successive prolongations of border controls. (Mouzourakis, 2018: 6, emphasis added)

The reintroduction of internal borders was possible because of the Schengen Border Codes, an addendum to the Schengen Agreement and EU Law. The premise for creating the Border Codes is unsurprisingly in line with what the ECRE has observed about EU policy discourse and how it “places particular emphasis on combatting irregular migration” yet without defining exactly what irregular means. Nevertheless, “irregularity” is what is being monitored and controlled not only at the “level of access to the territory” (Schengen Area entry points, a handful of states as mentioned above) but also on an intra-territorial dimension. The frictionless promise and premise of the Schengen area can be suspended on the basis of the above-mentioned irregularity, but also on a similarly ill-defined “context of foreseeable events”. The latter often includes “terrorist threats”, as well as the equally poorly defined term of “ secondary movements”, or simply having a “land border” with a state that is a Schengen Area entry point (e.g. Austria justifies its current period of reintroduction of Border Codes based on “secondary movements, risk related terrorist and organized crime, situation at the external borders; land borders with Hungary and Slovenia”.[4]

The exceptionality of irregularity and the future threat cast as foreseeable event are the two bases onto which countries part of Schengen Agreement can introduce these internal borders:

At the moment, temporarily reintroduced internal border controls are maintained by France on all of its borders, Austria on the Hungarian and Slovenian land borders, Germany on its Austrian land border, Denmark on its German border, Sweden on nearly all of its borders, and Norway on all of its borders. With the exception of France, which motivates the reintroduction of border controls on the basis of terrorist threats, these countries maintain internal border controls on the ground of ‘security threats’ arising from ‘continuous secondary movements’ of migrants in Europe. Where internal border controls are reintroduced, the relevant provisions of the Schengen Border Codes relating to controls at the external borders apply mutatis mutandis to such border crossings, implying that persons not complying with entry conditions and not belonging to one of the groups listed in Article 6(5) must be issued a refusal of entry. (Mouzourakis, 2018: 8, emphasis added)

As seen from these documents and the wide application of Border Codes under various ambiguous and unspecific terms, what happens at intra-Schengen borders in the EU is a state of generalised exception. Giorgio Agamben takes the camps as prime sites of exception and argues that it “has become an important, if not constitutive, metaphor of modernity, an ideal space of governance, order, categorization and discipline that in multiple forms functions as the necessary but uncomfortable and sometimes disavowed support of the reproduction of ‘normal’ citizenship and community life” (Agamben 1998: 166–80). What Weheliye, against Agamben, proposes is that the exception is perpetual for racialized bodies and therefore the exception does not provide any valuable interest or lens for understanding the law or how it works. The camp or asylum only leave one with “bare life” and the law. Moreover, having a body before the law (habeas corpus) only makes one more trapped in the inconsistencies, exceptions and, as seen in the Schengen Border Codes, vaguely defined territory of its conditions. In the case of “bare life” the predominant lexicon becomes that of resistance and in that of habeas corpus, subjection only takes place through legal agency. According to Weheliye, both rely on a conception and assumption of “full, self-present and coherent subjects” (2014a: 1). Thus, the crux of the matter is not having a body or being before the law but a much larger question of how the law defines the category of the human. In other words, for Weheliye this is a question of habeas viscus (having flesh) versus habeas corpus (having body before the law) or Agamben’s “bare life”. One exists other than before the law, as fleshly body, as embodied. The mode of being before the law assumes either subsumption or resistance as two major lenses and lexicons to see and speak the human through. These have a “prerequisite comparative tabulation of suffering” (Weheliye 2014a: 1) meaning that bodies are either granted status of human or gain it. This happens most often on the basis of the law, biology and economy and the result is a parsing out of fully human, not-quite-human, non-human.

This over-reliance on the law and having a body before it (habeas corpus) is one side of the coin to the Agambean “bare life”, of barely having a constituting position that does not amount to much because it is confined to the space of the camp. What Weheliye points out is how this reasoning, which Agamben undertakes, produces a trap for the conceptual potential of “bare life” as it “falls victim to a legal dogmatism that equates humanity and personhood with a status bequeathed or revoked by juridical sovereignty in much the same way as human rights discourse and habeas corpus do” (2014a: 131). But most importantly, for the context and situation discussed in the case of states like Italy and Austria and the current rise in right-wing immigration agendas seen in continuity with their respective fascist pasts, the promise of revolution in historical-materialist terms as expressed by Marx, W.E.B. Du Bois or Benjamin is excised in Agamben and what is left is a “defanged legal messianism far removed from the traditions of the oppressed” (2014a: 132). Weheliye critiques Agamben for his omission and disregard of the Benjaminian postulates which come from historical materialism and the role of the oppressed in instating a “real state of exception”, that is an excavation into the past and a revolutionary mission carrying with it the pedagogies of the oppressed. Instead, Agamben asks for rupture through redemption and fulfilment of a past inheritance or task. In turn, Weheliye argues for habeas viscus as he rests on the multitude of work done by black feminist authors such as Hortense Spillers and Saidiya Hartman in the histories of chattel slavery and the Middle Passage, and the varied pedagogies of the vagrant and fugitive flesh, which have amounted from these authors’ insights. What their lessons build towards, for Weheliye, against the overly cited white philosophers heralding the logic of measurement, calculation and law is that “habeas viscus diverges from the discourses and institutions that yoke the flesh to political violence in the modus of deviance” (2014a: 130). The critique to the subsumption and resistance binary, which Weheliye underscores his project on maintains the revolutionary as a constant in the experiences, histories and pedagogies emerging from black suffering. He is nevertheless mindful not to turn deviance into the spectacular and instead aims towards fugitivity as ground for thinking the human.

EU Law as Racialized Assemblage

“The dream of governance in general, is to go beyond representation as a form of sovereignty.” (Harney and Moten 2013: 56)

How does racialized infrastructure work in the Schengen Area and in the generalized case of application of Border Codes for intra-Schengen movement? Recently, Brexit as the sovereign fiction of the U.K. has become a reality and it will introduce even further friction at border points such as Calais. Concomitantly, it has triggered other European Union nation states, like Italy, to ask for “exits”. Italy considering leaving the European Union is arguably part of a larger “desperate times require desperate measures” type of discourse, which started with threats of leaving the Schengen agreement (Schengen Visa Info, 2019). What Matteo Salvini was hoping to achieve with this threat was precisely to make sure that asylum seekers are not able to cross in-between borders inside of the Schengen area. His argument had been constructed around EU states not respecting entry laws, as an issue of intra-European state friction: “We are forced to do so, as the Italian law is not being respected by the Dutch government, in compliance with the European Union.” What he then suggested was that a direct consequence of this would be that refugees and asylum seekers can travel between Schengen states freely, which was already not true, because Italy and Austria had imposed irregular checks since Border Codes were introduced. The exceptionalism of the law was already there and it already ruled at the moment it was demanded, based on even further exceptionalism.

The suspension of the Schengen Agreement can only happen in exceptional circumstances. The General Secretary of the European Trade Union, Luca Visentini made note of one founding premise of law-making, that every rule has an exception but claimed that there is no exception in this case; therefore, Italy’s demands to exit the Agreement were denied. Visentini even went on to state that suspension is not a solution because “asylum seekers […] are already being checked by the border police.” The argument is de facto the following: the Schengen agreement is in place and respected, there is no exceptional situation, therefore Italy’s claim is unfounded and there are no grounds for leaving the agreement. At the same time the border checks (not a norm but not yet considered an exception either) are also in place, so there cannot be free movement of asylum seekers in between Schengen states. Firstly, it comes as a consequence that some legal body or authority had already been decided this at some point in the past but not made public; it is already a form of exception since the free movement and no border checks of EU-registered population was supposed to be guaranteed by the Schengen agreement itself. Furthermore, once asylum seekers are registered in EU databases, they should also be able to move freely inside of EU. However, the Secretary’s statement suggests that a “more is more” approach is taken as the border controls are “going out of [their] way to check ‘free’ movement at the border, asylum seekers are identified and denied entrance in certain countries.” Secondly, this already existing exception that is perpetual is projected and amplified into the future: “border police, […] are currently doing a great job and are, if anything, short on personnel and resources, as the Police trade unions have rightly pointed out.” The increase in police powers and in the collaborative practices of police across Schengen states has already been enabled by the Prüm convention and treaty of 2005, when Schengen state police authorities were given capabilities for “cross-border observations and chases have been made possible as well as the exchange of data (fingerprints, DNA, vehicles)” (Van der Woude 2020: 125).

The over-arching consequence of increased policing powers and the experience in Austria show that once out of Italy, where they have been registered, migrants travelling across Schengen borders are going to be treated as un-registered “uncontrolled migrants” once more, as if they had just entered Fortress Europe. Austrian border police collaborates with Italian border police and also with non-border police forces in both states to enforce this logic of risk to national security–they are behaving as if Salvini’s threat has already taken into action, as if the “fore-seeable event” has been indeed foreseen and thus is being acted upon.

With the Border Codes being in place at different times and for various reasons, it is unlikely that the wider population would have knowledge of which and what exception stands, which intra-Schengen border checks apply and when they are deemed legal or not. However, the abuses around intra-border checks have already been documented by ECRE since 2017, for each country. Here are the notes for Italy:

Beyond well-reported barriers to disembarkation in Italian ports in the course of 2018, access to the territory by land is equally problematic. Since the end of February 2017, readmission measures have been initiated against people arriving in Italy from Austria via train. Controls have reportedly been based on racial profiling, intercepting mostly Afghan and Pakistani nationals. Italian authorities apply more stringent controls on regional trains arriving from Austria. If people do not hold valid documentation to enter Italy, they are immediately directed back to the same train by which they arrived, to travel towards Innsbruck, Wörgl and Kufstein [detention centers]. People are not provided with written notifications or explanations of the reasons for their readmission. They are not allowed to seek asylum or to benefit from linguistic assistance and their individual circumstances are not examined. (Mouzourakis 2018: 12, emphasis added)

The collaboration of these two states started before the exceptional provisions of the Border Codes applied and some of the observations from the reports now extend to those holding valid documents. It makes it not only confusing to those being checked but also a logical conundrum, as was the case in the policing instance I witnessed: holders of valid documents, having been issued asylum seeker papers in Italy, have exited the state to travel in a Schengen space of the neighboring Austrian territory. They are denied re-entry into Italy because they do not hold EU passports, and directed to re-start the asylum seeking process in Austria. Notwithstanding the complications and possible risk of detention camps or direct deportation, had they received asylum seeker papers from Austria, they would still be unable to return to Italy on the same grounds, namely that they do not hold EU passports but only travel permits, which again do grant them the right to pass by the 1951 Refugee Convention. It simply does not make sense and it also applies in reverse; the ECRE general report mentions for Austria:

A similar practice is applied vis-à-vis trains following the opposite direction along the Italian border. According to the testimonies of migrants returned to Italy, when police intercepts people coming from Italy, it orders them to return to Italy without starting of (sic) any formal procedure or without providing them with a written decision. Migrants have reported not being able to communicate with the Austrian police and to express their intention to seek asylum or–in some cases–to declare their minor age, namely due to the absence of linguistic mediators. (Mouzourakis 2018: 13, emphasis added)

Although these practices have been documented prior to the introduction of Border Codes, the “threat” had always already been there at least as far as these two countries were concerned and they were already acting on it, transforming the small nodes such as the Villach train station in Austria into detention-like spaces, extending the exception spatially into the racialized infrastructures of the Schengen space. The end goal and the undisclosed “threat” being fought against has been reducing the number of registered asylum seekers in the EU databases. As an excerpt from AIDA Austria country report (Knapp, 2018) goes to show, the quotas for asylum seeking applications granted are reduced every year: 37.500 (2016) to 30.000 (2017, 2018) to 25.000 (2019)–including family reunification cases. Further to the Schengen Border Codes, Austria released the Austrian Asylum Act in 2016, including the provision of quotas and an emergency regime, which will allow, when the quotas are reached, the Austrian authorities “to reject people who make an asylum application at the border before providing them with the opportunity to formally lodge their application” (Mouzourakis 2018: 10), as the general report mentions. The specific Austrian report goes on to explain that: “in 2016, ‘special provisions to maintain public order during border checks’ were added to the Asylum Act. When the provision (discussed publicly as ‘emergency provision’) enters into force through a decree of the federal government, asylum seekers no longer have access to the asylum procedure in Austria” (Knapp 2018: 18). Thus, not only is Austria using all the provisions that the Schengen Border Codes allow in terms of intra-state border controls, but it makes sure to stretch the realm of what a national-level legislator can do under a supranational legal framework like that of the EU. Van der Wounde’s (2020) study on multi-scalar border and criminal law aspects involved in the application of Schengen Border Codes supports what I have outlined so far in this article. Van der Wounde mentions article 23 of the Schengen Border Codes, which allows countries to exercise police powers and to carry out identity checks.[5] A set of issues are involved in this multi-scalar framework. Firstly, the performance of jurisdiction becomes negotiated on the ground inside and between different policing forces, depending on the capacities and structures of each nation state (with Italy and Portugal for instance reporting the involvement of armed forces, alongside immigration authorities, customs and border guard agencies). Secondly, as per provisions of article 23, these checks cannot be performed at the border, so they are done within a short range of the border (one small train station before the border, as in the case of Villach in Austria). Thirdly, the legal mandate on which these checks operate is “a mixture of administrative and criminal law” and thus “equipping enforcement agencies with both crime and immigration powers and responsibilities” (Van der Woude 2020: 119). The reason for this mixture is the initial basis onto which the Border Codes and the exception of free intra-Schengen mobility argument have been constructed–as a threat to national security.

Certainly, nation-state interest is directed to a racially-informed control of the population and the actions of measuring, calculation and tabulation are important for the exercising of this control, yet I argue that it is valuable to start from the propositions Weheliye makes about the everydayness and everynightness of having flesh/having a body in an always already racialized assemblage. This assemblage contains and is in relationship with law-making operations and policy, and the racist infrastructure part of racial capitalism, which became globally “hyper-apparent in the ‘War on Terror’, where the link between the two and how the terror-industrial complex feeds into (infra)structural violence of the everyday” (Rana 2016: 124). Infrastructural racism and biopolitical calculations form articulations “of the flesh as a racializing assemblage in the world of Man [which] cannot be apprehended by legal recognition and inclusion” (Weheliye 73). What is needed, according to Weheliye is the “disarticulation of the flesh from the law” as a disarticulation of flesh and property or more conceptually, a disarticulation and decoupling from both “bare life and from Habeas Corpus.” This sits in tension with Agamben and his conception of “state of exception” and “bare life” as “exclusively legal categories” and rests on a longer tradition of critical thinking on oppression coming from black writers such as Frantz Fanon and Sylvia Wynter, on whom Weheliye relies to argue that the major problem with “bare life” is that “Agamben fails to introduce any sort of invention into existence […] and for him invention can occur only after the abolition of present life” (Weheliye 2014a: 83). What modalities of existence does, in turn, the Weheliyan habeas viscus conjure up? The project at stake here is “imagining the relational ontological totality of the human” (2014a: 4) in the context of racial capitalism and racial infrastructures.

The railway station in the small town of Villach, Austria acted as the setting for witnessing acts of border policing that not only should not have happened at the border itself, given the right to movement of people across Schengen states (including, in this case, asylum seekers with registration papers from a Schengen country–issued by the Italian authorities), but should definitely not have happened in a town approximately 20 km away from the Austrian border with the North of Italy. This article so far has paid close attention to a single, small node and a moment of policing not as an exceptional case, but as a way of engaging with the multi-scalar issues of racialized infrastructure and bordering practices. It has shown how Italian and Austrian officers engaged in collaborative border policing of this town as if this was indeed the border, and not a simple node in the frictionless travel promises of the Schengen area, including for those already registered as asylum seekers in one Schengen state. Their actions, as Van der Wounde’s study clearly expresses, is a mixture of criminal law and immigration law being enforced at the intersection of Italian and Austrian jurisdictions. This not being in fact a border and those policing it not being in fact immigration officers but having been given legal jurisdiction over bodies, they drew the border with these bodies. Clearly not a question of being sans papiers, since documentation was held and shown, it remained unclear and unexplained by either Austrian police or Italian Carabinieri why passports were required in this case. As the reports cited in the previous section have shown, the push from Austria and Italy to introduce internal border controls in the Schengen area has been coupled with racial profiling and increased checks on trains. But if the studies cited mostly referred to those seeking asylum and aiming to get to Italy to do so, then the experience witnessed in this small train station shows how similar profiling, checks and refusal of entry applies to those who have already been documented and are seeking to return to the issuing country.

So far, I have argued that this experience shows how the added Border Codes to the Schengen Agreement and additional law-making that the Austrian and Italian governments have compiled in their creation of legal states of exception only contribute to an erosion of the human, producing “the universalizing of exception [which] disables thinking humanity creatively” (Weheliye 2014a: 11). It shows how modern racializing assemblages reinstate what Fred Moten and Stefano Harney have called “the dream of governance”, which they argue is “to go beyond representation as a form of sovereignty, to auto-generating representation, in the double sense. Those who can represent themselves will also be those who re-present themselves as interests in one and the same move, collapsing the distinction” (2013: 56, emphasis added). This node underlines the promise of the Schengen area towards state sovereignty and its ambition of going beyond representation, yet remaining inside the realms of governanance, of legal representation, of habeas corpus presenting itself before the law. What this instance shows is that the dream of sovereignty and that of biopolitical calculation, tabulation, measure and control need the state of exception to co-function in this particular space that is the Schengen Area.

Schengen as Promise of Frictionless Sovereignty

“Relationality is frictional.” (Tsing 2006, cited in Kaiser and Thiele: 4)

The European Schengen Area is arguably a specific type of imagined space for frictionless sovereignty. The promise of the Schengen area is free movement of goods and people, the promise of a friction-less territory, and also a promise of state sovereignty maintained. This double promise, as shown so far, has historically, even from its constituting moments, been hard to keep. The law is the point where the double bind in the promise becomes a tension, particularly in the hinging of frictionless sovereignty. The existence and application of Schengen Border Codes, when read in their relation to the racial infrastructures of Fortress Europe and the state of exception making bodies into borders, also bring into relation the areas that “rub the wrong way” in both the promise of free movement and the fiction that is sovereignty. This section will build on previously mentioned Weheliyan critiques of the messianic in Agamben’s conception, and juxtapose these to the notion of friction as situated, relational, and embodied. I interpret these frictions as opening up what Fred Moten calls the “the illusory coherence in/and spatio-temporal constitution of sovereignty” (2017, emphasis added). This maintained illusion of coherence is part of a larger condition of the sovereign, what Moten reading Frantz Fanon highlights as a neurosis, “the habitual attempt to regulate the general, generative disorder” (2013: 137). For the neurosis driven by the sovereign condition there is no space for expression, for affirmation given to flesh unless it is considered bare life, even if that space comes into being through the friction of nation states in various states of exception, legal or not. The questions of sovereignty and bodies, sovereignty and death in the sense of calculation, power, and control is something that Achille Mbembe takes up via Giorgio Agamben through a discussion of bare or mere life and necropolitics. Recognising Mbembe’s contribution, this is nevertheless a line of argument this article is aiming to critique, particularly insofar as in it, a passage happens from human “into the categories of meat and of flesh, of being reduced to mere and simple life” (Mbembe 2005: 161). Yet flesh, when not abstracted in this way, moves, shakes and makes visible the illusory coherence of sovereignty, as Weheliye argues. Flesh makes this illusion crumble in more than one way. The aspect of sovereignty that refers to exerting power on bare life as calculation and control is what comes into question when having flesh becomes central to understanding the infra-structural and legal constitutions of sovereignty as racialized assemblages. This stands in opposition to a view of sovereignty as “a mark of something originary, of a will that is self-born and unaccountable,” something apparent in Carl Schmitt’s work on political theology (Hansen and Stepputat 2005: 15).

As one of Agamben’s prominent influences, Carl Schmitt’s work has been picked up in critical theory with some consideration given to his central role in the German Nazi party but surprisingly, with a good degree of academic redemption. “In Schmitt’s view, sovereignty does not have the form of law; it lies behind, and makes possible the authority of the law” (Hansen and Stepputat 2005: 16). Weheliye states that Agamben “infuses [his work] with Carl Schmitt’s thoughts on sovereignty” (2014a: 33). Agamben takes from Schmitt the premise that the sovereign decides on the state of exception and that this is part and parcel of the law. Furthermore, Agamben engages with sovereign power over bodies and populations through bare life, making possible the reduction of life to an abstracted form of flesh, only visible when it appears in calculation. As Weheliye shows, Agamben insists on the bond with and abandonment to the law of every living being but does not address the fact that the “the state of exception does not apply equally to all, since the exclusion of and violence perpetrated against some groups is anchored in the law” (Weheliye 2014a: 87). For Schmitt, where Agamben takes his influence, “the Earth is bound to Law” (Schmitt 1950: 42) and “nomos is the measure by which land in a particular order is divided an situated” (Schmitt, 1950, 71) therefore tabulation, calculation and measurement are inherently bound to law. The nomos is of and in the Earth, and the law is in there too, bound up with the Earth. Thus, any exception to this relation between law and Earth belongs to the powers of the sovereign and it is a legal decision. In other words, the decisions of the sovereign are also bound up with law and Earth (soil and blood) and they are legal decisions. In Schmitt’s later work, The Nomos of The Earth (1950) there seems to be a shift from the sovereign decision central to his earlier work to nomos because this term “emphasizes much more the idea of ‘concrete order’” (Antaki 2004: 323). In the next section, I will focus on how Schmitt’s arguments about the nomos have been criticized for holding the illusory coherence of sovereignty, if not through decisionism, perhaps even more worryingly, though an argument of bounded-ness, of friction-less relation between law, soil, of divvying up and parcelling out that extends from colonial thought and disregards whole sections of populations as belonging to the category of the human.

Map and Territory: Also a Question of the Human

“The existence of black life disenchants Western humanism.” (Weheliye 2014b: 5)

To return to the main points raised in the first section of this article and the central argument in Weheliye’s project: the concept under critical revision is that of the human, as an assemblage accounting for gender, racialization, coloniality, slavery, political violence, especially shaped and sharpened in the work of Sylvia Wynter and Hortense Spillers. The challenge of this revision rests in centring black feminist epistemology “without mapping these questions [of the human] onto a mutually exclusive struggle between either the free-flowing terra nullius of the universally applicable or the terra cognitus of the ethnographically detained” (Weheliye 2014a: 24, my emphasis).

Terra nullius as principle in International Law has been set in place to justify claims that territory may be acquired by a state’s occupation of it. It implies, of course, that before occupation, this was the territory of feral beasts, human or non-human. Terra nullius is also, not surprisingly, the legal term connected to the Berlin Conference (1884-5) and the colonial occupation in the African continent. What conception of the human can then arise from the idea of “the free-flowing terra nullius of the universally applicable”? Whiteness, imperialism, the world of Man and that of colonialist occupation function as ontological and epistemological grounds.

On the other hand, terra cognitus designates the known, the acquainted with but also the tried and proved, the knowledge stemming corporeally, from the body and from lived experience. This, however is the knowledge of Man, hence the play on gender in the formulation Weheliye chooses in Latin; this is undoubtedly the terra cognitus of the world of Man. What conception of the human arises from “the terra cognitus of the ethnographically detained”? Weheliye argues that what arises is the particular epistemology, the exception and the particular land claim that are often relegated to identitarian claims and stuck in the space associated with the group identity, or of territory associated with that identity. He continues by stating that in the Western epistemological system of value, black studies has been relegated to the disciplinary particular of ethnic studies, ethnographically detained, and that this relegation has been doubled by a disregard for black life which “has represented a negative ontological ground for the Western order of things at least for the last five hundred years” (Weheliye 2014b: 5). He goes on to argue that the underlining ground for this epistemological parsing has at its core a dichotomy between black life and other types of life, whereas black studies understands the human “not [as] an ontological fait accompli” (Weheliye 2014a: 7). If the human is not a given, completed and bound up in legal structures dictated by the sovereign by decision, the human should also not be defined and bound up by the world of Man, particularly through nomos. Quite the opposite, as Anna Jurkevics underlines, following Hannah Arendt, “the nomos should stay open to contestation in the future. The world and the nomos are rooted and concrete, but not static, in the Arendtian conception” (Jurkevics 2017: 358).

If the nomos stays open to contestation then the question of the human can move between the universal and the particular, between identity and rootedness into a space or territory with the situated knowledge that arises from that position, conceptualizing and making sense of human experience as a whole. What we could define as human thus interfaces between these positions and spaces, mapping and parsing out through the entangled dimensions these open up, rather than belonging to one or the other.

For Schmitt, the word nomos (law) is primordially and primarily tied to land and opens up questions of excess and exception. In what follows, I will consider Jurkevics’s article, which engages with Hannah Arendt’s indirect critiques of Schmitt and particularly with his view of nomos as intrinsically imperial and racist, which will bring us back to Weheliye’s argument on the racialized assemblage of legal and institutional infrastructures and the question of the human, once more.

This critique of Schmitt is put together by Anna Jurkevics in her research resting on evidence from marginalia written by Hannah Arendt in her copy of Nomos of the Earth, pointing to what she calls “an incisive critique of Schmitt’s geopolitics and International Law” (2017: 346). Jurkevics argues that the relevance of this find is not purely identifying a never published historical conversation but that its implications are mostly contemporary. According to her article, in the U.S. context and academic debate Arendt’s notes on the book open up new and important questions on the use of Schmitt’s concept of nomos in scholarly work as “a tool against American empire in the post 9/11 era” (Jurkevics 2017: 1). One could say that by extension, this critique could have effect on how Schmitt’s work has been deployed in critical conversations around risk, terror threats and attacks. In the case of Europe, the EU and Schengen area, the intrinsically imperialist nomos that Fortress Europe is enforcing as violent geopolitics could expose the use of Schmitt’s concept into critical questioning as well. Jurkevics argues that a scholarly deployment of Schmitt “will have to grapple a contradiction, exposed by Arendt, that lies at the core of Schmitt’s geopolitics, namely that he both embraces conquest and repudiates imperialism” (2017: 346).

Europe is bound to law, exception is also law and to be human means to have a body before that law. This opens up implications for the Jus Publicum Europaeum–the principle of equality of states in International Law, as it was codified in Europe in 1814. If we follow Arendt’s critique of nomos, as a philosophical as well as historical concept, it is apparent that for Schmitt this concept is “based on the idea of land-appropriation, and is thus imperialist” (Jurkevics 2017: 352) and that this appropriation happens primarily through conquest. Such is the history of European Law defined through conquest of territories outside of it. This imperialist set of legal prescriptions in tied into the history of European law-making through colonialism and it has structural implications on how any current legal configurations, like the Schengen Agreement and the Schengen Border Codes can be considered as lawful, especially towards those bodies whom could be considered worthy of standing before these laws of Man:

Arendt’s concern about justice comes out most vehemently in her comments about Schmitt’s history of colonialism. In this account, some land-appropriations established a new nomos while others did not. Schmitt is interested in understanding the land-appropriations that constituted a new nomos; he is not interested in the wrongs that resulted from them. Arendt responds firmly: ‘‘that jurists do not know what justice is does not give Schmitt the right to equate injustice and law-making.’’ (marginalia: 50). Arendt wants him to admit that these land-appropriations are unjust, are the original sin of a new order, instead of equating them with law. (Jurkevics 2017: 351)

Essentially, the central questions that Arendt raises are around what the source of law is, according to Schmitt and also, where is it situated? Jurkevics clarifies that most likely Schmitt’s answer would be “that law springs from the soil in the moment that it is captured, cultivated, and bounded” (Jurkevics 2017: 349). Citing Arendt’s further marginalia in her own copy of The Nomos of The Earth, Jurkevics provides an answer to a later issue stemming from the same problem of nomos, as Arendt had seen it: the fact that “Schmitt misunderstood that Nazi ideology was, in the first place, racist, not geopolitical (marginalia: 211)” (cited in Jurkevics 2017: 349). As plurality does not feature for Schmitt in the same way that it plays a role in understanding the relationship between law and politics for Arendt, “she complains repeatedly that people, human beings, are cut out of his account” (Jurkevics 2017: 349) and the focus is on earth as soil and battleground. These sites of conquest are for Schmitt central to law-making and thus, as central sites of conquest and abuse, as the linguistic source of the word nomos itself indicates (from nemein, as nehmen/to take and as teilen/to divide).

Land-capture or occupation or conquest is obviously the sine qua non of land-division. But questions of right first arise with division, which accords each his own- …questions of right come about during the divvying up of the New World only once it comes to division…before the acquisition comes the division and not conquest! (marginalia: 108) (Jukevics 2017: 352)

This key point in Arendt’s critique rests on the fact that for Schmitt, appropriation comes before division, which is essentially an imperialist view. Parsing out land and making territory is preceded by conquest and Arendt raises questions of right around divvying up processes, like those involved in colonial conquest and their role in justifying and legitimating a historically fascist European rule. If Arendt’s marginalia notes have served here to compose a grounded critique of Schmitt, then that is their limit and the reason is mainly Arendt’s own anti-Black racism as pointed out in growing contemporary scholarship on Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism (1962), On Violence (1970) and most strikingly, Reflections on Little Rock (1959). For example, in a reading of On Violence, Chad Kautzer makes the case that mobilizing Arendt’s ideas about the instrumentality of violence as a resource in producing critical reading of contemporary violence could risk giving way to spaces where her thinking is “complicit with the violent logic of a different order” (Kautzer 2019: 2). That order, Kautzer goes on to argue, is that of legal and state violence, especially when considered as a racialized assemblage, meaning a constellation which enforces the role of the white vigilante and “charges those who resist it with breaching the peace” (2019: 1). The reason for the former is that Arendt did not directly address state violence which emerges through social issues and particularly structural racism and white privilege, even when writing at the time of International decolonial struggles and the height of the Black Power movement in the United States. She consistently ignored the issue of structural state racism and actively deemed black liberation movements that involved forms of violence as “irrational, provocative and […] clearly unjustified” (Kautzer 2019: 11), going as far as arguing that there is an inherent “lawlessness” to Black communities, which makes them responsible for further “white backlash” (Arendt, 1968 cited in Kautzer 2019: 10). These readings are echoed in Patricia Owens’ analysis of the ideas put forth in On Violence. Apart from “her consistent refusal to analyse the colonial and imperial origins of racial conflict in the United States” (Owens 2017: 403), Arendt also openly disagrees with Sartre and Fanon, refuses to recognize the Third World as a transnational site in decolonial struggles, and considers it a mere inversion of imperialist ideas of territory, concocted by the European New Left. She thus excises any agency from the proponents of these struggles in these sites in the world and re-centers European knowledge production as a site of power. Furthermore, if in The Origins of Totalitarianism Arendt makes “dubious attempts to sever the historical and political link between racism in America and the forms of imperial racism” (Owens 2017: 414) then in The Human Condition she states in no unclear terms: “universal experience is not a substitute for particularity and plurality” (Owens 2017: 416).

In short, translating to the issues raised in this article so far, Arendt, who has been extensively cited in contemporary scholarship on European migration deals with imperialism and colonialism in the same terms, drawing up divisions between nature and culture and between terra nullius and terra cognitus, tensions between the universal of the terra nullius and the particular of identitarian land claims. She replicates exactly the same division, which further down the argumentative line leads her to the question of the human. Most explicitly in works like The Human Condition, Arendt draws divisions between those “more or less ‘cultured’, more or less free, and thus more or less fully human” (Owens 2017: 412). She might not rely on evolutionism but reaches the same anti-Black conclusion, which makes her deem African tribal communities as never fully human (Owens 2017: 412). The Euro-centrism and anti-primitivism that Arendt upholds throughout her work thus falls into the same world of Man, as the white colonial rule over land and people, where law incorporates everything. Overall, this amounts to an argument that stands together with a third critic of Arendt’s most obvious anti-Black racist piece, Reflections on Little Rock, Michael D. Burroughs (2015: 52), who writes that it is “white ignorance [which] constitutes a fundamental epistemic error” for Arendt’s line of argumentation.

Divvying, even when division precedes conquest as Arendt’s correction of Schmitt shows, is an ontological and epistemological form of violence, when the human is conceived through the world of Man. It excludes the possibility of being for anything outside of the figure of Man as the secular, modern and Western version of the human. Weheliye’s propositions insist on disarticulating the flesh from the law, and call for imagining a modality of existence that is tied up neither with the sovereign nor the nomos. For Weheliye, miniscule moments, shards of hope, scraps of food “swarm the ether of Man’s legal apparatus, which does not mean that these formations annul the brutal validity of bare life, biopolitics, necropolitics, social death, or racializing assemblages but that Man’s juridical machine can never exhaust the plentitude of our world” (Weheliye 2014a: 131). In this process of disarticulation, which follows black thought and lived experience foremost, we could start to hopefully think and be with “enfleshed modalities of humanity” (ibid: 13).

Conclusion

This article has emerged from an experience of witnessing how European Law is enacted on racialized bodies during current anti-immigration efforts of nation-states that are part of the European Schengen territories, like Italy and Austria. It has offered an abstracted reflection on how the human body, in its enfleshed being, becomes the border, even when the promise of no borders marks the foundations of such a project of friction-less sovereignty. Europe is bound to law and an essential source of European Law’s mutation over centuries of application into its current wide-reaching iteration is imperial and colonial violence based in conquest of soil, bodies, and blood. Academic thought upon which we often rest our critiques of these laws replicate anti-black and other forms of racism stemming from the liberal humanities of the world of Man. Black scholars and black studies have consistently offered knowledge and experience, which should be considered sources and not alternatives to the current challenge of thinking the human and beyond. The aim has been to centre this knowledge in the interpretation of current bordering practices, which try to make bodies appear before the law through enforcement and articulation. What became apparent in setting an event against the legal framework of Schengen Border Codes, regulatory regimes, and jurisdictions is that the border becomes visible in the “hieroglyphs of flesh” Weheliye mentions, producing friction in the dream and promise of frictionless sovereignty.

Mihaela Brebenel is a screen and visual studies researcher. They are interested in feminist and queer practices, as well as the aesthetics and politics of screen (and other) technologies. They work as Lecturer in Digital Cultures at Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton and are part of Archaeologies of Media and Technology Research group.

References

Agamben, Giorgio (1998) Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Antaki, Mark (2004) “Carl Schmitt’s Nomos of the Earth.” Osgoode Hall Law Journal. 42:2, 317–34.

Arendt, Hannah (1959) “Reflections on Little Rock.” Dissent, 6:1, 45-56.

— (1962) The Origins of Totalitarianism. Cleveland: Meridian Books.

— (1970) On Violence. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.

Bove, Caterina (2018) “Country Report – Italy | Asylum Information Database.” European Council for Refugees and Exiles (ECRE). https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/italy. Accessed: 25 September 2019.

Brar, Dhanveer Singh (2014) “Hieroglyphs of the Flesh.” new formations: a journal of culture/theory/politics 83(1), 144-146.

Burroughs, Michael (2015) “Hannah Arendt, ‘Reflections on Little Rock,’ and White Ignorance.” Critical Philosophy of Race 3:1, 52–78.

Césaire, Aimé (1955) Discourse on Colonialism, trans. Joan Pinkham. Reprint, New York: Monthly Review Press, 1972.

Schengen Visa Info (2019) “ETUC: Italy Leaving Schengen, Means Isolating Itself From Europe”. Published: 8 July 2019, https://www.schengenvisainfo.com/news/etuc-italy-leaving-schengen-means-isolating-itself-from-europe/ Accessed: October 2019.

Hansen, Thomas Blom and Finn Stepputat (eds.) (2005) Sovereign Bodies: Citizens, Migrants, and States in the Postcolonial World. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Harney, Stefano and Fred Moten (2013) The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study. Wivenhoe: Minor Compositions.

Hartman, Saidiya V. (2010) Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press.

— (2019) Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Jurkevics, Anna (2017) “Hannah Arendt Reads Carl Schmitt’s The Nomos of the Earth: A Dialogue on Law and Geopolitics from the Margins.” European Journal of Political Theory European Journal of Political Theory 16:3, 345–66.

Kaiser, Birgit, M. and Katrin Thiele (2018) “Returning (to) the Question of the Human. An Introduction.” PhiloSOPHIA 8:1, 1–17.

Kautzer, Chad (2019) “Political Violence and Race: A Critique of Hannah Arendt.” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 21:3.

Knapp, Anny (2018) “Country Report – Austria | Asylum Information Database.” European Council for Refugees and Exiles (ECRE). https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/austria. Accessed: 25 September 2019.

Lewis R. Gordon (ed.) A Companion to African-American Studies, Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 107–18.

Mbembe, Achille (2009) “Sovereignty as a Form of Expenditure” in Hansen, Stepputat (eds) Sovereign Bodies: Citizens, Migrants, and States in the Postcolonial World. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 148–69.

— (2017) Critique of Black Reason, trans. Laurent Dubois. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

McKittrick, Katherine (ed.) (2015) Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Moten, Fred (2017) Black and Blur. Consent Not to Be a Single Being. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Mouzourakis, Minos (2018) “Access to Protection in Europe. Borders and Entry into the Territory.” Asylum Information Database: European Council for Refugees and Exiles (ECRE). https://www.asylumineurope.org/2018-iii.

Opratko, Benjamin (2020) “Austria’s Green Party Will Pay a High Price for Its

Dangerous Alliance with the Right.” The Guardian, 9 January 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jan/09/austria-greens-right-peoples-party-anti-immigration.

Owens, Patricia (2017) “Racism in the Theory Canon: Hannah Arendt and ‘the One Great Crime in Which America Was Never Involved’.” Millennium 45:3, 403–24.

Rana, Junaid (2016) “The Racial Infrastructure of the Terror-Industrial Complex.” Social Text 34:4, 111–38.

Rodríguez, Dylan (2016) “Los Angeles’ Coalition Against Police Abuse (CAPA) and the Obsolescence of White Academic Raciality” in Zurn and Dilts (eds.) Active Intolerance. Michel Foucault, The Prison Information Group, and the Future of Abolition. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.145-169.

Schengen Visa Info. 2019. “ETUC: Italy Leaving Schengen, Means Isolating Itself from Europe.” Accessed 15 May 2020. https://www.schengenvisainfo.com/news/etuc-italy-leaving-schengen-means-isolating-itself-from-europe.

Schmitt, Carl (1950) The Nomos of the Earth in the International Law of the Jus Publicum Europaeum. New York: Telos Press Publishing.

“Travel Documents – Italy | Asylum Information Database.” https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/italy/content-international-protection/movement-and-mobility/travel-documents, accessed 24 September 2019.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt (2015) Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Van der Woude M. (2019) “A Patchwork of Intra-Schengen Policing: Border Games over National Identity and National Sovereignty. ” Theoretical Criminology 24:1, 110–31.

Weheliye, Alexander G. (2014a) Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Weheliye, Alexander G. (2014b) “Introduction.” The Black Scholar 44:2, 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/00064246.2014.11413682.

Wynter, Sylvia (2006) “On How We Mistook the Map for the Territory, and Reimprisoned Ourselves in Our Unbearable Wrongness of Being, Of Désêtre” in Lewis R. Gordon (ed.) A Companion to African-American Studies, Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 107–18.

[1] “The Asylum Information Database is a database managed by ECRE, containing information on asylum procedures, reception conditions, detention and content of international protection across 23 European countries. This includes 20 European Union (EU) Member States (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Germany, Spain, France, Greece, Croatia, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Sweden, Slovenia, and United Kingdom) and 3 non-EU countries (Switzerland, Serbia, Turkey).”n.p.

[1] I would like to thank Ryan Bishop for his editorial guidance and patient support in the development of this article and beyond. Scott Wark, Grace Tillyard, Peter Rees and Charlotte Terrell have made this time of academic writing in quarantine feel nurturing by offering great support on versions of this article. Thank you also to peers Ilona Jurkonytė and Nikolaus Perneczky for your careful notes and attention to the script. And in the most heartfelt way to Ariya, for her ways of holding space and being present.

[2] In Austria’s case, the more recent and insidious collaboration of the Green Party with known conservative parties in supporting anti-immigration policies is particularly notable. See Oprakto (2020).

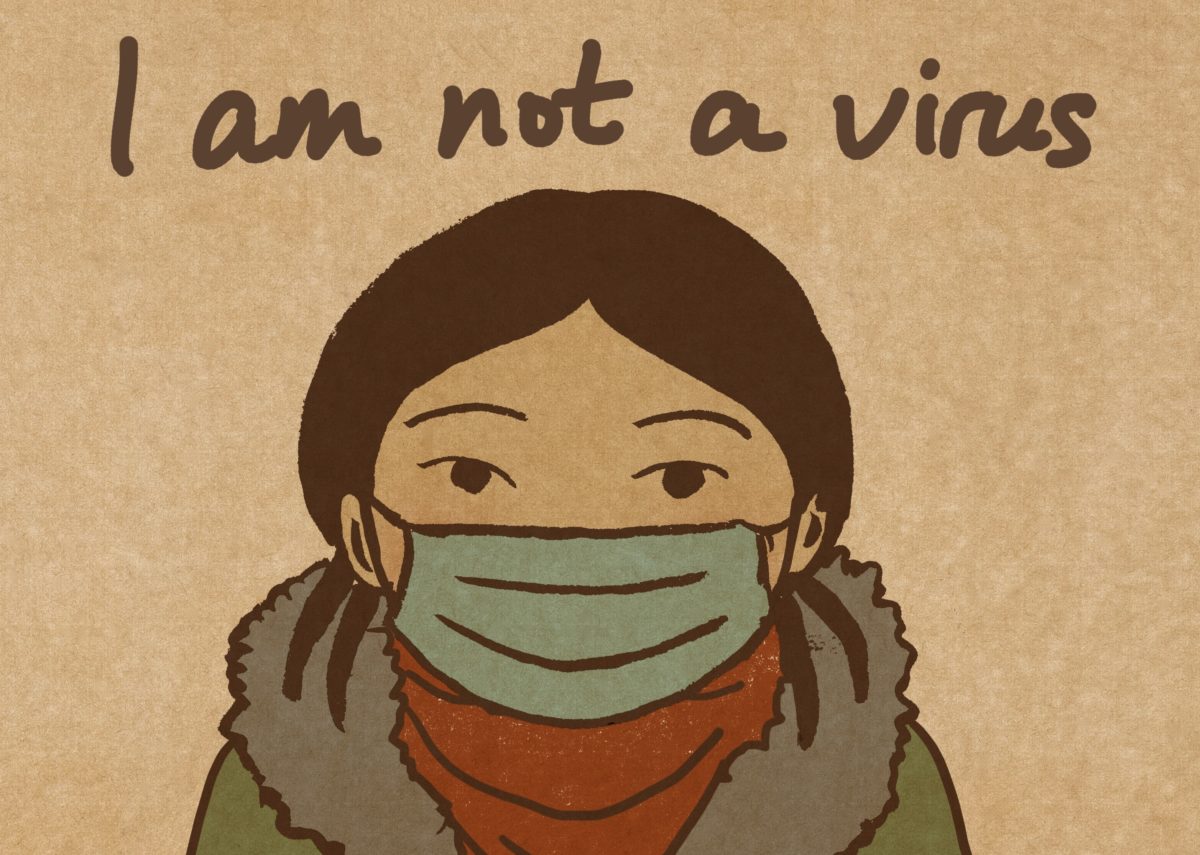

[3] The rush to close borders in between Schengen states has never been more clear than in the current pandemic, where with the outbreak of COVID 19, there has been a return to hard borders between all EU member states, again leaving refugees and asylum seekers outside of the structures of care they are legally and humanly entitled to.

[4] https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/borders-and-visas/schengen/reintroduction-border-control_en

[5] Article 23 states that these discretionary policing activities can take place as long as “(1) the exercise of these powers cannot be considered equivalent to the exercise of border checks, (2) the police measures do not have border control as an objective, (3) are based on general police information and experience regarding possible threats to public security and aim, in particular, to combat cross-border crime and, lastly, (4) as long as the measures are devised and executed in a manner clearly distinct from systematic checks on persons at the external borders and are carried out on the basis of spot-checks” (Van der Woude 2020, 118).