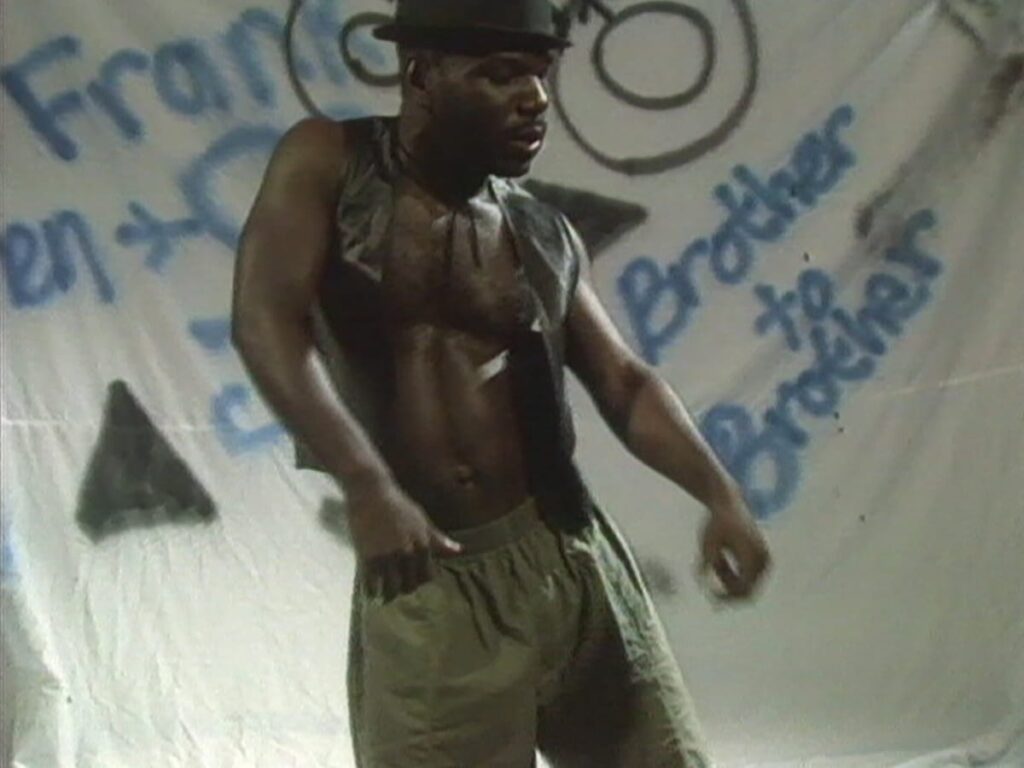

Marlon Riggs, Anthem, 1991, film still. Copyright Signifyin’ Works, by courtesy of Frameline Distribution.

This article is part of the b2o: an online journal special issue “(Rhy)pistemologies”, edited by Erin Graff Zivin.

Black Queer Cadence: Hearing as Diasporic Seeing

Jamal Batts

Rhythm is as central to Black film as it is to the blackness of life. I’m interested in thinking about sound as foundational to what scholar Darius Bost terms the Black Gay Cultural Renaissance of the 1970s, 80s and 90s, might provide a reading of works from this era. Here, I will take two paths toward a theory of sound in and as Black queer diasporic cinema. I will reserve my comments to two interrelated elements, rhythm and the voice. I will work to draw out how the filmmaker Marlon Riggs’s montage and poet Essex Hemphill’s voice in various experimental film works lay a rhythmic mark on the constellation of the varied labors referred to as Black film.

One unlikely source to begin thinking the itinerary of rhythm and Black queer film might be scholar Robeson Taj Frazier’s recently published book KAOS Theory: The Afro-Kosmic Ark of Ben Caldwell, about experimental L.A. Rebellion filmmaker Ben Caldwell’s astro-grounded aesthetics. Caldwell, the founder of KAOS Network—a media arts education center and performance space in historically Black Leimert Park—produces work that evinces an artistic hydraulics which moves across scales. In remarks delivered during the 1992 Black Popular Culture conference filmmaker, Arthur Jafa, Caldwell’s former student at Howard University, proposes an aesthetic agenda for the Black filmmaker—to transpose the tonality and movement of Black music into the making of Black film. In Jafa’s forward to KAOS Theory, he reveals that it is in Caldwell’s work where he first encounters what he terms a “fully realized jazz cinema” (Jafa 2023: 6). Frazier’s work guides the reader through the aesthetic maneuvers that visualize this improvisatory impulse in Caldwell’s visual practice, or what scholar Fumi Okiji might describe as “the play, the wrestling and cooperation, of disparate parts” that is the “fecund blackness” of jazz (Okiji 2018: 6, 4).

In the 1980s, Caldwell co-founded the performance ensemble Hollywatts which included actor Roger Guenveur Smith, musicians Mark Broyard and Vernon “King Oji” Vanoy, and filmmaker Wesley Groves. Hollywatts employed video work, hip-hop, reggae, vocalization, theater, and musicianship in order to forge uncommon connections amongst distinct community formations. Their performances and Caldwell’s film works were projected on site via monitors controlled by Caldwell and Groves. Their projections were manipulated in such a way that they would tremble, pause, deform, and play in reverse—a live improvised rhythmic visual response to the sounds of Hollywatts’s musical performance (Batts 2024). Hollywatts’s practice gave presence to the always immanent liveness of the moving image. Caldwell’s and Groves’ skill as filmmakers and projectionists “enabled Roger to engage in a call-and-response with the videos; he would ask the screen a question, and Ben’s edited videos answered with an image or cinematic sequence. Then the image was rewound and reshown when Roger repeated the question or made a statement, he and the screen engaging in back-and-forth chant” (Frazier 2023: 178).

In this essay, I argue that much of the Black queer experimental film of the 1980s and 90s, considered in the most expansive of terms, utilizes both sonic and visual rhythms to challenge the racializing mechanisms that seek to submerge the queer potency of blackness across the Black diaspora. This work, resonant with Hollywatts’s extension of the cinematic via Black sonic methodologies (i.e. call-and-response), is conversant with Michael Gillespie’s concept film blackness, which seeks to “[suspend] the idea of black film by pushing for a more expansive understanding of blackness and cinema” (Gillespie 2016: 5). Gillespie queries “What do we mean when we say black film? Black directors, actors, or content?…What does the designation black film promise, and what does it disallow?” (5). Part of the impetus for this line of questioning is to expand the objects and modes of study available for understanding how blackness becomes visible on screen and the variegated work its figuration performs. The avant-garde musical methodologies employed in experimental Black queer cinema offer a potent avenue for thinking the import of (Black) sexuality, in its filmic deployment, as a rhythmic-visual tool advancing a processual blackness.

Visual Polyrhythms

In his forward to KAOS Theory, Jafa describes a scene from Caldwell’s 1977 film I&I: An African Allegory that makes me see Riggs’s 1991 experimental film Anthem with new eyes. Anthem is an 8-minute short film/music video soundtracked by house music, punctuated pauses in the rhythm, and a whiplash sound effect. Riggs dances in front of a white tarp graffitied in memorialization to the late Joseph Beam, the progenitor of Black gay cultural production as the editor of the first anthology of Black gay men’s poetry and prose. Certain motifs flash briefly but effectively, punching through the frame and rhythmically playing as what could be termed imagistic beats interrupting the moving image. I’m most interested in the still images of drag queens and trans women, including the legendary activist Marsha P. Johnson, which work in the montage alongside Riggs’s image and stock footage of West African dance from the continent. Although, as Stuart Hall has argued, we always risk the flattening of Africa with the excision of context, the images of moving and leaping bodies conspire to both thicken and collapse our vision of time (Hall 1989). I would argue that this is accomplished through rhythm.

The house music that is played throughout is given a visual polyrhythm via figures whose appearance does not necessarily align with the metronomic back beat of the music, but form their own contrapuntal incision. This maneuver is heightened in scenes of dance filmed at Club Bella Napoli (the dancers are listed as the Bella Boys in the credits). The scenes give off the feeling of a strobe light, where vision oscillates between granular clarity and complete darkness. The metaphorical strobes do not align with the soundtrack, much like in Riggs’s experimental documentary from 1991, Tongues United, where still newspaper obituary photographs of those who have died from AIDS-related complications are flashed sullenly in and out of time with the sound of a heartbeat and then a fast-ticking clock, ending with a picture of the director himself in preparation for his own certain death. I would place the sound of (Riggs’s?) heartbeat in dialogue with the mimetic sound of the heart in another experimental short film/music video from the era; white filmmaker John Sanborn’s Untitled (1989), an impassioned exploration of choreographer Bill T. Jones’s grief for and memory of his late partner and collaborator Arnie Zane through dance, montage, and music. The video ends with Jones forcefully and rhythmically beating his chest, the sound and echo giving the impression of a powerful though slowing heart in motion as Sanborn gradually pans the camera away from Jones and the lights fade to black, leaving Jones in the otherworldly place of his deceased partner’s voice, which provides the background for the film.

In Anthem, as in Tongues and Untitled, it is as if the beat were a form of rhythmic visual accumulation. In Jafa’s elaboration of Caldwell’s film I&I, he focuses on “a sequence… composed entirely of black-and-white still images that triggered such a shift in my thinking, that I’m still working out its implications… There’s a staccato montage of images that demonstrated conclusively the possibility of imposing on cinema the feel and flow of black music” (Jafa 2023: 16). Caldwell’s mixing of photographer Diane Arbus’s imagery with Black representations leads Jafa to ask “How was it” then, “black cinema?” and Caldwell’s later work made Jafa question “Does cinema have any potential therapeutic value?” (7). I’m interested in this provocation to questioning because it speaks to Gillespie’s assertion that “black film is always a question, never an answer” (Gillespie 2016: 16). Potentially, a focus on the rhythm of film blackness, as opposed to the Black on film, can go some way toward keeping the collapse of racial “referent and representation” in abeyance (2). Other still images that Riggs calls upon to flash on screen are ACT UP’s slogan Silence = Death, the American flag, and the Pan-African flag in red, black, and green. At the end of the video, all of these images flash, waver, and visually layer as blues musician Blackberri sings “America” a cappella while Hemphill, looking directly at the camera, confidently recites in his deep voice, with a slight lisp, the words to his poem “American Wedding,” here an erotic suture to a mesh of moving imagery without certain confluence.

The film is, in an aslant way, conversant with Caldwell’s Hollywatts and what Frazier describes as the group’s use of certain “film/video images” and “audio cues” as “predetermined ‘constants [which] served as the groups collective metronome supplying them with the foundational indicators, cues, and steady pulse to perform and ‘play in time.’ It was within the gaps and breaks between these cues that they experimented, improvised, and cultivated new interpretations. Such improvisatory shifts were often rhythmic…” (Frazier 2023: 178). The use of improvisation as a technique in the cutting and editing of sound and video—a visual rearticulation of jazz improvisation—allows for readings of blackness as recombinant and always already in process as opposed to fixed (Linscott 2016). Thinking with Riggs’s Anthem as improvising with the prerecorded audio of Black queer house music, American and Pan-African visual and sonic iconography, archival still images of Black queer life, movement imagery, and stock and pre-recorded footage opens a new texture for considering the ways in which his work signifies an ongoingness, an enduring aesthetic and corporeal beat at some distance from the registers of mourning, melancholia, and political malaise and toward what Aliyyah Abdur-Rahman calls the Black ecstatic or “black queer… representational practices that punctuate the awful now with the joys and possibilities of the beyond (of alternate worlds and ways)” (Abdur-Rahman 2018: 344). Riggs’s non-linear, rhythmic, and arrhythmic experimental juxtapositions of video and sound picture compressed, dense, and compassionate relations out of step with normative scripts and clock time, allowing for dynamic, mutable, and vital interpretations.

The Black Queer Ensemblic

In the DVD extras from the Frameline distributed version of Marlon Riggs’ Tongues Untied there is footage of poet Essex Hemphill practicing his narration for the documentary. Unlike the talking head footage featured in the actual film, here Hemphill’s head is for the most part faced down, looking at the pages from which he’s reading as opposed to the direct and straightforward glare he delivers in Tongues. When he does look up from the page, it’s an obvious look behind the camera at Riggs as if for approval. He looks to the director, a fellow Black gay man, for confidence as to his delivery. Two things stand out to me about these images. The first, is my own surprise at seeing Hemphill unsure of himself. On screen, both visually and vocally there is an assuredness to his posture and tone that did not prepare me for Hemphill in rehearsal for his part, in the process of steadying his body for the screen.

There’s much yet to be written on Hemphill. There’s that striking voice, its particular grain evoking the work it was put to across open mics, college campuses, bookstores, and films throughout his life. His voice is special. There’s a reason it was so often utilized. It’s the anoriginary Black queer vocal, strong and sensual, the erotic considering the pornographic, a vocal caress (Lorde 1984). It has the quality of leadership in its steadfastness, found consequential under a context of heightened premature death. His voice could also be read at the level of pace, the quality of his pauses and repetition. His masterful control of his instrument, from the page to film, is why hearing difference in that voice is so shocking; like when his voice cracks when facing his mortality as an ambivalent Person with AIDS at the Black Nations/Queer Nations? conference in 1995. His is also a voice that requested a complement. His live performance work was often performed in chorus. What would it mean to read that replayed instrument that is the materiality of Hemphill’s voice on film as music?

The second aspect of this footage that draws my attention is its focus on the sound of the voice. Hemphill and Riggs share moments of poetic dialogue, reciting poems meant to be read in tandem, that require their voices to layer and rhythmically meld. At one point in this behind-the-scenes footage, Riggs admonishes himself for forgetting to pause as Hemphill had suggested. His rereading of the text is lovely, varying mightily in tone, intonation, and texture as to communicate the anguish of silence and the multitude of inscriptions it bears. The intense focus on sound between two stars of the Black Gay Renaissance reveals a keen understanding of its import in this moment. In particular, the sound of Hemphill’s voice is a leitmotif in Black queer cinema. It is utilized in Riggs’s films Tongues Untied, Anthem, and Black Is…Black Ain’t (1995), Isaac Julien’s Looking for Langston (1989), Aishah Simmons’ No! A Rape Documentary (2006), Ada Gay Griffin and Michelle Parkerson’s A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde (1995), and as the narrator’s voice in a documentary on Black gay men and transgender women based in Philadelphia titled Out of the Shadows.

If, as Amy Lawrence has argued, the projection of the seamless convergence of sound and image that is film produces a “fantasmic body” which Mary Ann Doane refers to as a “unity, cohesion, and hence, an identity… holding at bay the potential trauma of dispersal, dismemberment, difference,” then it could be reasonably argued that Hemphill’s voice is an indispensable joint that holds together a Black queer body (in pieces) (Lawrence 1992: 179; Doane 1980: 45). I, of course, use the term “joint” here in reference to Brent Hayes Edward’s deployment of the term in his elaboration of the underexplored gaps between the politics and cultural productions of diasporic and Pan-African artists and organizers thought to be a cohesive body. As Edwards theorizes, “The joint is a curious place, as it is both the point of separation… and the point of linkage… Articulation is always a strange and ambivalent gesture, because finally, in the body, it is only difference—the separation between the bones and members—that allows movement” (Edwards 2001: 66). I want to consider this difference as movement via the voice of Hemphill as it crosses the ocean between the United States and Britain in two films that feature his voice (as well as that of blues singer Blackberri).

Both Julien and Riggs highlight a number of Hemphill’s poems and share one entitled “Now We Think.” Julien, in Looking for Langston, uses the work during a sparsely decorated scene where a Black man sits while watching a pornographic film. Alone, Hemphill shares the well-known words “Now we think, as we fuck, this nut might, kill us” in a rather straightforward manner. The film pictures the Black man cropped in shadows, smoking a cigarette with close ups of his mouth. When the poem mentions the possibility of “a pin-sized hole in the condom, a lethal leak,” Julien cuts to a close up on his pursed lips with the slightest of openings. At the mention of a kiss, the lips reappear. When Hemphill utters “turn to stone,” there is a cut to the making of a statue. As with the majority of the film, the scene is full of potential associations and unanswered questions. Hemphill never appears but is gestured toward by imagistic substitutes. His voice is a specter, a potentiality for the image but not its dictation.[1]

In Riggs’s Tongues, Hemphill performs the work with his frequent collaborator Wayson Jones. The scene is embellished by a pig latin version of the line “now we think as we fuck” (repeated rhythmically by Jones in the background throughout) and quick visual fades between Hemphill and Jones that intensify in pace as the poem accelerates. For the majority of the poem Hemphill’s voice is contained and steady, but as his reading proceeds his voice becomes more brash and emphatic, ultimately leading to his sensual and panicked belting of the line “this nut might…” repeatedly in a crescendo that ends with his unexpectedly composed and quiet recitation of the words “kill us.” The scene concludes with Hemphill and Jones delivering shared orgasmic moans to the camera, mouths wide in ecstasy. The filmic rhythm of the poem is slowed and then quickened to enact an erotic intensity.

The scenes share an interest in the gaze. However, in Julien’s work the subject looks past the audience toward his own projected screen, whereas in Riggs’s work you are the desired, a direct interpolation into sensuality, the hoped for other to the “we.” There’s also an emphasis placed on the line “sucking mustaches” in Julien’s film not present in Riggs’s. The erotic intensity of these scenes, work with different vocal paces and volumes; they stimulate differing affects, punctuating and overlaying the deathly stakes of the AIDS crisis. They offer various direct and clipped orations and introspective muted tones, a Black queer ensemble under the influence of a singular voice.[2]

There are numerous understudied and untraveled pathways for thinking sound and Black queerness on film. The cacophony of sound and image that Black queer film instances may be the raucous band that forms the polyrhythm of blackness in and as what Okiji refers to as “sociomusical play;” here, around the terms of sensuality (Okiji 2018: 4). In the defiance of form located in the rhythms of jazz and house music, Black queer experimental cinema finds fugitive movements that refract and recompose the terms of blackness and sexuality in a moment of acute narrative constriction, risk, and crisis for Black life. Play and improvisation with the structure of visuality through rhythm provides lines of flight from the imperatives of racialized erotic restraint, punctuating convivial and unexpected relations across time. To focus on the sound of the visual, and the visual of sound might give us a peek into the unruly intramural sociality of Black and queer as entangled, relational, and stereophonic forces.

References

Batts, Jamal. 2024. “Toward a Black Alternative Media: On Robeson Taj Frazier’s ‘KAOS Theory.’” Los Angeles Review of Books, April 30, 2024. lareviewofbooks.org/article/toward-a-black-alternative-media-on-robeson-taj-fraziers-kaos-theory/.

Bost, Darius. 2019. Evidence of Being: The Black Gay Cultural Renaissance and the Politics of Violence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Carroll, Rachel Jane. 2023. “What Can Beauty Do?” In For Pleasure: Race, Experimentalism, and Aesthetics, 39–86. New York: New York University Press.

Doane, Mary Ann. 1980. “The Voice in the Cinema: The Articulation of Body and Space.” Yale French Studies 60:33–50.

Edwards, Brent Hayes. 2001. “The Uses of Diaspora.” Social Text 19 (1): 45–73.

Frazier, Robeson Taj, and Ben Caldwell. 2023. KAOS Theory: The Afro-Kosmic Ark of Ben Caldwell. Los Angeles, CA: Angel City Press.

Gillespie, Michael Boyce. 2016. Film Blackness: American Cinema and the Idea of Black Film. Duke University Press.

Gilroy, Paul. 1998. “It’s A Family Affair.” In Black Popular Culture, edited by Gina Dent, 310–15. New York: The New Press.

Hall, Stuart. 1989. “Cultural Identity and Diaspora.” Framework 36: 222–37.

Jafa, Arthur. 1998. “69.” In Black Popular Culture, edited by Gina Dent, 249–54. New York: The New Press.

Jafa, Arthur, Robeson Taj Frazier, and Ben Caldwell. 2023. “Forward.” In KAOS Theory: The Afro-Kosmic Ark of Ben Caldwell, 6–7. Los Angeles: Angel City Press.

Julien, Isaac, dir. 1989. Looking for Langston. Strand Home Video.

———. 1994. “Confessions of a Snow Queen: Notes on the Making of The Attendant.” Critical Quarterly 36 (1): 120–26.

Lawrence, Amy. 1992. “Women’s Voices in Third World Cinema.” In Sound Theory/Sound Practice, 178–90. New York: Routledge.

Linscott, Charles “Chip” P. 2016. “In a (Not So) Silent Way: Listening Past Black Visuality in Symbiopsychotaxiplasm.” Black Camera 8 (1): 169–90.

Lorde, Audre. 1984. “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power.” In Sister Outsider: Essays & Speeches, 53–59. Freedom, CA: The Crossing Press.

Moten, Fred. 2017. “The New International of Rhythmic Feel/Ings.” In Black and Blur, 86–117. Durham: Duke University Press.

Neumeyer, David. 2019. “Studying Music and Screen Media.” In The Routledge Companion to Music and Visual Culture, edited by Tim Shephard and Anne Leonard, 67–74. New York: Routledge.

Riggs, Marlon, dir. 1989. Tongues Untied. Frameline.

———, dir. 1991. Anthem. Frameline.

Sanborn, John, dir. 1989. Untitled. Electronic Arts Intermix.

Stilwell, Robynn. 2007. “The Fantastical Gap between Diegetic and Nondiegetic.” In Beyond the Soundtrack, edited by Daniel Goldmark, Lawrence Kramer, and Richard Leppert, 184–202. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Notes

[1] Robynn Stilwell refers to filmmakers’ play with diegetic (a part of the story) and nondiegetic (outside of the story) sound as the “fantastical gap,” a visual-sonic in betweenness that allows for the subversion of viewers’ aural expectations. Rachel Jane Carroll notes Julien’s use of this technique with house music and the sound of the ocean in Looking for Langston as ways of probing identification and diasporic loss and connectivity. See Stilwell 2007. See Neumeyer 2019. See Carroll 2023.

[2] In much the way that Fred Moten in “The New International of Rhythmic Feel/ings” reads a productive and “sexual politics” in the disagreements of Black diasporic musicians who seek to exceptionalize the national character of their Black music and its genres (while disallowed from entry into the national family) the work of Riggs found strife in diaspora; critics who, including Julien, read an essentializing impulse in Riggs’s work in terms of racialized desire and masculinity. Instead of plotting Riggs and Julien as combative aesthetic forces, I read the way they rhythmically play with the same instrument, Hemphill’s voice, as a shared though tenuous desire in the making and positioning of difference as an unfixed commitment to new creative potentialities. Their relation is generatively posed as disjunctively choral due to the history and present of blackness and its spatial dispersion. See Moten 2017. See Julien 1994. See Gilroy 1998.