This Intervention is published as part of the b2o Review’s “Stop the Right” dossier.

Nasty Politics[1]

Johs Rasmussen

No single heuristic can explain the current success of reactionary conservatism. The guiding thesis of this piece is nonetheless that a critical focus on feelings and aesthetics can help us identify some of the structural dynamics that buttress the popularization of far-right sentiments today.

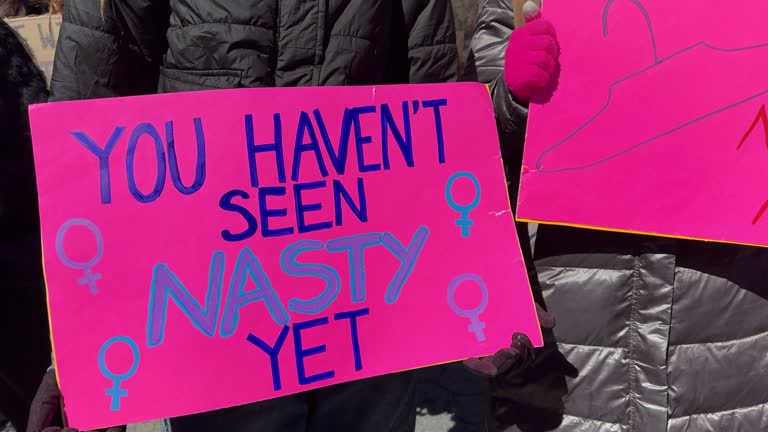

Consider Donald Trump, who, in addition to being in the engine room of the conservative “emotion machine,” also acts as a sort of incidental aesthetic practitioner and judge.[2] As the figurehead of a movement that is profoundly invested in aesthetics (in a memorandum published on January 20th this year, for example, the president directed that “Federal public buildings should… respect regional, traditional, and classical architectural heritage… to uplift and beautify public spaces and ennoble the United States and our system of self-government”),[3] Trump nurtures a distinct affinity—inseparable from his investment in a certain understanding of the beautiful—for the category of “the nasty.” Trump’s notion of the nasty cannot be untethered from his history with Hillary Clinton, whom he called “such a nasty woman” during the final debate before the 2016 presidential election. Since then, “nasty” has become a keyword in the Trumpian lexicon. While the term carries particularly spiteful connotations whenever he hurls it at women, the aspiring American strongman is nothing if not liberal in his exercise of this judgment.

“Nasty” is much more than a trivial term. From an analytical perspective, the rhetorical uses of the nasty only represent one aspect of its emotional, aesthetic, and political valences. Characterized by a relational hostility and the always-implicit judgment of that which is other to the nasty (beauty, pleasantness, or righteousness, for example), the category is not bound to a single figure. It rather signifies an important nodal point in a robust system of taste that prevails among the political right. Trump is its most prominent exponent, but the spirit of the nasty is embedded throughout the spheres of law, culture, and politics, as symptomatized by Republicans’ reallocation of government resources (for example, denying food assistance to the poor, or rapidly expanding the state’s ability to purge the nation of immigrants) and the Supreme Court’s rescripting of key legal principles (criminalizing abortion, or imposing censorship on LGBTQ+ inclusive literature in public schools). Even the conspicuously named One Big Beautiful Bill Act calls attention to the bifurcation of a right-wing notion of beauty and its nasty other. Originally framed as a personal attack, nastiness has evidently been recast as a structural feature of conservative rule in the United States, so that, as a feeling, aesthetic mode, and judgment, it now names the organizing logic of a system of taste that suffuses autocratic politics.[4]

Defining the Nasty

The affective and aesthetic register of “the nasty,” I argue, most effectively indexes the antagonisms of our catastrophe-ridden present. As Sianne Ngai remarks in Ugly Feelings (2005), emotions and their attendant aesthetic registers always call “attention to a real social experience and a certain kind of historical truth.”[5] In Stolen Pride: Loss, Shame, and the Rise of the Right (2024), Arlie Russell Hochschild likewise posits that the root causes of emotions, even though they feel utterly personal, always “lie in larger social circumstances.”[6] With this structural entanglement in mind, the emergence of the nasty as a prevailing emotion, aesthetic mode, and key of judgment in the twenty-first century suggests that its careful study can reveal something about the historical forces that permeate the rise of the right.

In recent years, a considerable amount of public-facing and critical scholarship has examined how emotions such as shame, fear, loss, and resentment are tethered to the widespread embrace of far-right ideas.[7] The nasty cannot be unmoored from these other affective states. For example, the paranoia and sense of cultural loss that undergirds “the conspiratorial belief that educators are indoctrinating innocent children against whiteness and heterosexuality” exhibit the structural characteristics of nastiness since such feelings intimate that the curriculum must be stripped of whatever elements that contaminate the conservative Weltanschauung.[8]

In some respects, the category of the nasty thus resembles what Ngai calls “ugly feelings.” However, unlike the affects she examines in her seminal book, the nasty can hardly be described as a “minor” mode of feeling and judging. If the postindustrial knowledge economy’s functional differentiation of labor called for the scrutiny of “animatedness” and “stuplimity,” then American conservatives’ general espousal of election denial, anti-vaccination propaganda, and autocratic governance suggests the need for a critical vocabulary that is explicitly curious about the politics of aesthetics and emotion. Hence the nasty, which appears to share the “intense and unambivalent negativity” of disgust, an emotion which Ngai regards as “an outer limit or threshold of… ugly feelings” that brings us closer to “more instrumental or politically efficacious emotions.”[9] As a political feeling, “disgust” bespeaks “a fundamental refusal of another person’s full humanity,” writes Martha Nussbaum, which, so conceived, “seems pretty nasty.”[10] Nastiness and disgust do not index identical affective responses, aesthetic modes, or keys of judgment, yet as Nussbaum indicates, they share overlapping properties that, in each case, bring the realms of aesthetics and politics into proximity.

The OED defines the adjectival form of “nasty” as being characterized by filthiness, contemptibility, nausea, spite, unpleasantness, cruelty, and even moral corruption.[11] These associative words are affective anchors for reactionary ideas about “proper” social norms. The renunciation of LGBTQ+ culture and references to “the woke mind virus” come to mind as exemplary instances of conservatives exuding nastiness towards people who defy the normative conventions to which they ascribe. As an analytic, then, the nasty comes with significant political stakes, but it is still important to distinguish between the visceral, corporeal sense of nastiness, on the one hand, and how the nasty can be discursively appropriated in the service of moral and political causes, on the other. The literal feeling evoked by something judged to be nasty is not always aligned with the figurative valuation of something or someone as nasty. I can look at a pool of vomit without suddenly becoming enamored of authoritarianism. Even when they signify vastly different objects as nasty, however, the literal and figurative notions of this category contain an identical structure of experience: the nasty is propelled by categorical discrimination and a desire to “clean up.” Typified by intolerance, the nasty always demands a dogmatic judgment that rejects the object of evaluation and calls for its sanitization.

The nasty is predicated on a “vehement exclusion of the intolerable.”[12] This intolerance, as well as the affective and aesthetic sensibilities it brings about, is coded into the rhetorical uses of the analytic. Take Trump, who during this year alone has described Democrats as “nasty people who actually hate our Country”[13] and called the Episcopal Bishop Mariann Budde “a radical Left hard line Trump hater” who is “nasty in tone, and not compelling or smart.”[14] During the summer’s anti-ICE protests in Los Angeles, the president likewise remarked, during a speech at Fort Bragg, that the federal government would “liberate Los Angeles and make it free, clean, and safe”—decontaminate the city’s nasty underbelly, that is.[15] These comments are not just data points in an ever-growing linguistic corpus.[16] Rather, the sweeping deployment of both implicit and explicit references to nastiness represents a semantic key into a regime of politics that exhibits the major characteristics of the nasty, even if the language, actions, and legislation that interlocks with this regime of politics don’t always go by that name. Put another way, the category of the nasty synthesizes discursive formations, modes of behavior, and ideologically tinged fields of perception that are animated by a logic of total exclusion. In its most extreme rendition, this logic aims to eliminate that which exudes nastiness since there is no redemption for the nasty. It must be cleansed and sanitized.

The nasty constitutes an absolute politics that intersects with ideas that convey strict inside/outside boundaries (biological norms, nativism, law-abidance, etc.). Even so, the category hints at something slightly different from Walter Benjamin’s canonized diagnosis that the aestheticization of politics is a distinct feature of fascism. Certainly, the nasty embraces aesthetics and their emotional affordances, but the regime of politics it labels does not exist in a historical vacuum. As other contributors to the “Stop the Right” dossier have pointed out, the infrastructure of nasty politics has been built over many decades, with self-identifying liberals and neoliberals being as complicit in its construction as conservatives bent on purging the nation of anti-Americanism. Republicans may be fond of calling Barack Obama a “socialist,” but he is still the “sovereign of drone strikes.”[17] ICE detention levels increased incrementally every year during the Biden administration.[18] The financial and military backing of wars in the Middle East is not a unique feature of the incumbent administration. The American government has undertaken covert pro-US influencing campaigns in geopolitically sensitive locations throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, as it is doing in Greenland right now. And Trump’s magnetic sway over half of the voting populace in 2016 was supplemented not just by the radicalism of the Tea Party but also by the fanatic, universal embrace of the free-market ideology that has hollowed out public institutions since the 1980s.

So, while the category of the nasty helps distinguish the current regime of politics from its previous iterations, it is important to stress the historical continuity that suffuses the contemporary rendition of the political right. The state’s targeted harassment of non-white and vulnerable communities is unexceptional, as is the securitization of the imperial core from outside penetration. What is different is the vitriol with which mainstream conservatives now legitimize their ideological agenda. The widespread embrace of nastiness represents a radical break with the normative framework of neoliberal democracy. As constitutional crises abound and state-sponsored violence enacted against political enemies escalates, it becomes evident that something unprecedented is going on. The outrageous suspension of institutionalized mechanisms for protecting the citizenry (for example, habeas corpus) outlines, in no uncertain terms, who is deemed to belong to the body politic. As a loud, boisterous affect, aesthetic mode, and key of judgment, the nasty has not only eschewed the veil of moderate contempt behind which adherents of neoliberalism enacted some of the same policies as the two Trump administrations; it has also imbued this regime of politics with an unprecedented and uncompromising level of intolerance directed towards both real and imagined dissidents.

Nastiness in Reverse

In Our Aesthetic Categories (2012), her follow-up to Ugly Feelings, Ngai observes that “in this hyperaestheticized world neither art nor beautiful/sublime nature remains the obvious go-to model for reflecting on aesthetic experience as a whole.”[19] The nasty might not constitute such an “obvious go-to model,” either. Yet, considering the ascendancy of regimes of nasty politics across the globe, it is worthwhile to ponder which critical insights the category’s imbrication of feeling, aesthetic mode, and judgment yields. Elevating nastiness in this way might readily prompt defeatist interpretations of the contemporary aestheticization of politics, of course. The system of taste that organizes the political right is highly potent, and regardless of how you turn the screw, it remains difficult to imagine new emotional and aesthetic horizons that are as forceful as the nasty. But emotions and aesthetics need not be the exclusive property of right-wing ideology. As Jacques Rancière has argued, “there has never been any ‘aestheticization’ of politics in the modern age because politics is aesthetics in principle.”[20] If the popular currency of the nasty can be depreciated, it may be possible to “redistribute the sensible,” in Rancière’s terms, and elevate creative practices and modes of feeling that offer compelling aesthetic alternatives to nastiness.

So far, the political opposition in the United States has failed to envision such alternatives. Instead, in response to the Republican gerrymandering and the federal government exercising unconstitutional power against individual states, Democratic officials have leaned into a species of nasty politics, too. California intends to counter Texas’s redrawing of congressional district maps, for instance, and with Gavin Newsom as the driving force, they are farcically mocking Trump’s appearance, age, and style of communication on social media. The double bind of the right’s embrace of the nasty is that a regime which identifies “illegal” immigrants based on skin color, refuses entry to tourists in possession of doctored photos of the Vice President, and hosts military parades in celebration of the administration’s leader, inevitably invites dissent from people who keep fidelity to another system of taste. The proclamation of something as nasty can reasonably be expected to elicit a counterclaim by another who subscribes to a different set of affective and aesthetic norms. Even when articulated in a left-wing key, however, the nasty’s core principle of intolerance sets inflexible boundaries that at best can be instrumentalized towards the cynical end of raw power. An absolute politics of nastiness, regardless of its ideological origin, cannot reconcile the polarization that typifies the contemporary, nor can it form the foundation of even basic, non-violent coexistence.

Furthermore, Democrats’ embrace of the nasty appears to entail a paradox since a system of taste that foregrounds the nastiness I have profiled above will be at odds with the ideas and values they purport to defend (equality, inclusion, and so on). The nasty is categorically organized by exclusion, which seems to undermine the principle of pluralism that pervades the history of liberal and progressive thought in the United States. Hillary Clinton’s “basket of deplorables” might not have been intended as a discursive catalyst for the systemic implementation of nastiness on the right, but such propositions of relational hostility can hardly be construed as, nor be transformed into, semantic building blocks crafted to revive the nation’s crumbling civic culture. Unlike their Republican counterparts, the Democrats’ embrace of the nasty thus seems poorly suited as the spine of a political program, let alone a cultural movement. A logic of discrimination propels the nasty. Either something is nasty, or it is not. The category is ideal for a regime of politics that thrives on ostracization and naturalizes people’s belonging to, or expulsion from, a sovereign territory. Even if left-wing iterations of the nasty inspire dissent, the category must eventually be reenvisioned so that feeling registers, aesthetic modes, and vocabularies of judgment that aim at building better futures become more prominent. Precisely because liberals, progressives, and activists further to the left self-identify as dissenting from the right’s regime of politics, they should not be satisfied with replicating the political architecture of conservatism. In turning away from the nasty as an absolute politics, something more profound than a mere victory at the ballot box seems to be at stake.

There is a less suspicious way of reading dissidents’ appropriation of the political right’s rhetorical and aesthetic schemes, namely, as a tactic for diffusing the binarism that inheres in the nasty. Newsom’s sardonic riff on Trump’s communications style on social media (all caps, name-calling, outrageous and unsubstantiated claims) has caused Fox News pundits to call the California Governor childish and unserious. In doing so, they are, of course, also implicitly criticizing the progenitor of this mode of expression. When adapted to emphasize its internal contradictions, a caricatured recourse to the nasty might accordingly diminish the category’s vitality as a key vector in the system of taste that prevails on the right. (Importantly, such invocations of the nasty deviate from Clinton’s “basket of deplorables” and the species of civility it signified because they are much more self-aware of their status as nasty.) Whether a politics of caricature can nourish genuine defiance in the long run remains to be seen. I suspect that, sans an ability to imagine alternative creative practices, modes of feeling, and strategies for succeeding in what Hannah Arendt called “human living-together,” the nasty logic of absolutism won’t be expunged from American culture and politics.[21] To that point, the songs, artwork, and solidarity that spawned during the anti-ICE LA protests epitomize a cluster of energies that dissidents could tap into if they want to avoid the iteration of nastiness in a left-wing key. The revolutionary spirit of the BLM protests, in 2020 and earlier, represented another mode of public feeling that promoted a form of cohabitation which defied not just the political right but also ossified ideas such as hyperprivatization and uncurbed policing that suffuse neoliberal rationality.

If we are to realize a shared future, the spirit of nastiness that suffuses the structural rule of conservatism must be unconditionally reformed. That much is certain. The key point I have tried to raise, in conclusion, is that such a lofty goal cannot be reached without tapping into the political affordances of aesthetics and emotions.

Johs Rasmussen is a PhD Candidate in the Department of English at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is completing a dissertation, titled Nasty Emotions, which uses a range of literary texts, figures, and phenomena to examine how feelings such as fear, loneliness, envy, greed, and grief intersect with the umbrella category of “the nasty.”

[1] I would like to thank Arne De Boever and Russ Castronovo for their feedback on previous iterations of this argument.

[2] Lauren Berlant, “Trump, or Political Emotions,” The New Inquiry, August 5, 2016, https://thenewinquiry.com/trump-or-political-emotions/.

[3] https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/promoting-beautiful-federal-civic-architecture/

[4] For more on the autocratic features that characterize Trump’s presidency, see: Masha Gessen, Surviving Autocracy (Riverhead Books, 2020).

[5] Sianne Ngai, Ugly Feelings (Harvard University Press, 2005), 5.

[6] Arlie Russell Hochschild, Stolen Pride: Loss, Shame, and the Rise of the Right (The New Press, 2024), 11.

[7] For a snapshot of this scholarship, see for example: Katherine J. Cramer, The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker (University of Chicago Press, 2016); Arlie Russell Hochschild, Strangers In Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right (The New Press, 2016); Eva Illouz, The Emotional Life of Populism: How Fear, Disgust, Resentment, and Love Undermine Democracy (Polity Press, 2023); Rahel Jaeggi, “Modes of Regression: The Case of Ressentiment,” Critical Times 5, no. 3 (2022): 501–37; Andreas Reckwitz, Verlust: Ein Grundproblem Der Moderne (Suhrkamp, 2024); Richard Seymour, Disaster Nationalism: The Downfall of Liberal Civilization (Verso, 2024).

[8] Elisabeth R. Anker, “Ugly Freedoms and Insurrectionary Conspiracies,” in Theory Conspiracy, ed. Frida Beckman and Jeffrey R. Di Leo (Routledge, 2024), 117.

[9] Ngai, Ugly Feelings, 354.

[10] Martha C. Nussbaum, From Disgust to Humanity: Sexual Orientation and Constitutional Law (Oxford University Press, 2010), xiii.

[11] https://www.oed.com/dictionary/nasty_adj?tab=meaning_and_use#35369820

[12] Ngai, Ugly Feelings, 344.

[13] https://truthsocial.com/@realDonaldTrump/posts/114764131885531801

[14] https://truthsocial.com/@realDonaldTrump/posts/113870397327465225

[15] https://www.wunc.org/politics/2025-06-10/trump-liberate-los-angeles-250th-anniversary-army-ft-bragg

[16] In Nasty Politics: The Logic of Insults, Threats, and Incitement (2023, Oxford UP), political scientist Thomas Zeitzoff conducts a discursive analysis of how political actors, especially from the right, use nasty rhetoric to advance their ideological cause. While studies of this kind illuminate the sweeping use of the nasty as a rhetorical form, it does not examine the affective and aesthetic dimensions of the analytic.

[17] Seymour, Disaster Nationalism: The Downfall of Liberal Civilization, 98.

[18] TRAC, Immigration Detention Statistics: A Retrospective and a Look Forward (Syracuse University, 2025), https://tracreports.org/reports/753/#:~:text=During%20the%20Biden%20presidency%20detention,the%20end%20of%20FY%202023.

[19] Sianne Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting (Harvard University Press, 2012), 20.

[20] Jacques Rancière, Dis-Agreement: Politics and Philosophy (University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 58.

[21] In Arendt’s vocabulary, “human living-together” designates a form of pluralized social life that has as its highest ideal the flourishing of everyone in the human commons. Hannah Arendt, Origins of Totalitarianism (Harcourt Brace & Company, 1973), 478.