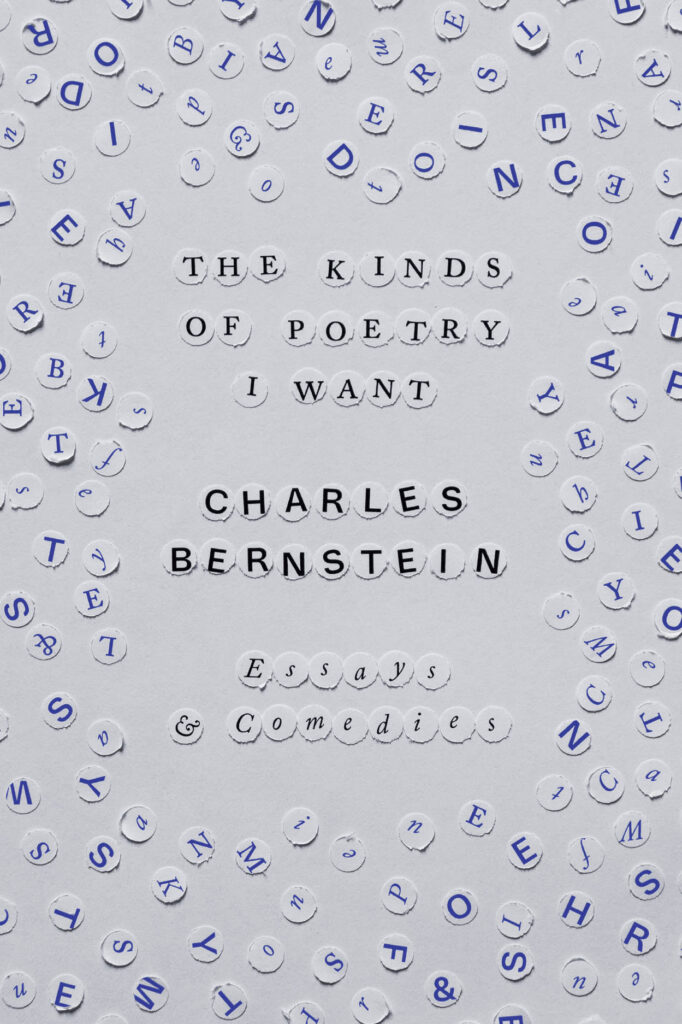

This text is part of a b2o Review dossier on Charles Bernstein’s The Kinds of Poetry I Want.

The Kinds of Responses I Want

Charles Bernstein

Manual Air Release

The end of the road

is the beginning

of the journey ––

so they say.

But I say

roads don’t

end, we just

lose our way.

Or is it find it?

The first time I was invited to give a talk at a university was at the invitation of William Spanos, co-founder of boundary 2 and a professor at SUNY-Binghamton. In The Kinds of Poetry I Want: Essays and Comedies, and as Bob Perelman recounts in his contribution to this special issue, I tell a story about leaving a copy of Paul de Man’s Resistance to Theory on the return plane ride. But I had first tried to make that trip to Binghamton months earlier. There was a fierce snowstorm that day in the early 1980s. I remember stopping at one of those on-the-road gas stations on the Jersey Turnpike — it’s probably still there. There was minus zero visibility, if there is such a thing. Still, characteristically, I decided to push on, and would have, if Susan hadn’t intervened. I could not contact Bill until I got back home to 464 Amsterdam Avenue, our tiny tenement apartment on the Upper West Side. He told me the storm had closed the university. I always felt connected to Bob Creeley’s “I Know a Man”: drive, he sd, for / christ’s sake, look / out where yr going. I am too often consumed by that impulse to drive, and too often I don’t exactly know where I am going. But I have my instincts.

I start with that story because you’ve got to begin somewhere, and I was reminded of it by Mark Wallace, who mentions a slightly later visit to Binghamton recounted in Kinds. Bill Spanos published my first “scholarly” article, “The Objects of Meaning: Reading Cavell Reading Wittgenstein,” in boundary 2 in 1981. I don’t recall any peer reviews or even comments by Spanos. That’s the way I like it — an iconic lyric of the time that Creeley repeated twice to make a poem: I like it / I like it.

My connection to this magazine has continued “through the years,” as another iconic lyric of that time goes — most recently with “Pre-Owned Poems,” published in boundary 2 last year. This forum follows up on Paul Bové’s Charles Bernstein: The Poetry of Idiomatic Insistence a few years ago, which mostly charted my non-US exchanges. Now, Arne De Boever and Christian Thorne have assembled this collective engagement with Kinds. Having a home base like this has been crucial, and I am grateful for it.

Mark Wallace writes his essay as a letter to me, knowing that I come alive most in conversation — both in agreements and disagreements (and some of the key works in Kinds are conversations and disagreements). That is where I tune up and test how far “offkey” I can be and still keep the melody or rhythm — or just hang on for sheer life when I lose both — as one lost in a snowstorm. Or found in it. Wallace quotes from Kinds: “I only know what I think when I am in conversation… Dialogue’s the center of what I do.” My essays, he says, “seem like responses not just to changing conditions but to the condition of change. Interactions. Questions. Avoidances. Refusals. Conversations.” That resonates with my own feeling that thought is a form of motion, and that sometimes, as he puts it, “a poem has to be dared into existence.”

Kacper Bartczak brings me back to Stanley Cavell’s “finding as founding,” another home base, and my echo of Cavell: losing as a faltering finding. Bartczak reads my poetics as radicalizing Cavell’s aversive practice, turning “finding as founding” into a poetics of provisionality and errancy. He sees the “event of the poem” as a suspension of settled meanings, where “losing as finding” becomes a mode of inhabiting language beyond rationalized closure. I don’t make light of loss, and I am surrounded by it — many essays in the new book are elegies or eulogies. Losing may just as well lead to nowhere, which is what it feels like to be bereft. But acknowledging that at least lets me find myself where I am.

Just as much as I wanted to get to Binghamton that day, I want to get reactions to what I write — want to hear how the work hits various ears: lands, or lands askew, or misfires. That’s what keeps me going, makes me feel I am working alongside other people. It buoys me in dark times and through thoughts turbulent.

Two of my closest poetry friends had different attitudes. Lyn Hejinian told me she didn’t like to read anything written about her work — didn’t want the response, even from supportive friends (and maybe especially from them), to spin her sense of what she was doing (though this may also have been related to the limited time she had left at the end of her life). She was referring to a new essay I had written about My Life (40 years after my first essay on the book), and it made me feel abandoned –– an unopened letter at the time of her death. (But Lyn always responded, and with full flower, to letters, right up to the end.) Maybe she was right — self-contained, not dependent on the heroin (or is it oxygen?) of response. Bob Perelman quotes the essay on My Life, reminding me that Hejinian’s refusal of closure intensifies the elegy, which is grouped with pieces by (then) living poets, rather than in the constellation of the dead called “Shadows.” My reflections on My Life is called “hung meanings.”

Leslie Scalapino was the opposite. She read responses religiously but would go ballistic when a proposed interpretation differed from what she intended. Her work is as “underdetermined” as you get, but she wanted readers to experience the aesthesis as she designed it. And she hated when enthusiastic readers read it in ways she did not intend. I would often say to Leslie that there is a sublime madness to that view, because you can’t control readers’ responses to such wildly open-ended work. But I appreciate that she extended intention to things the “intentionalists,” as described by Bartczak, would not countenance.

And it puts me in mind of what I meant … not to say, but to do. Because my poetry and essays are meant to create thinking/feeling fields, linguistic webs and folds in which readers and listeners become engaged and entangled, finding by responding. My intentions involve setting conditions, not conveying discrete packets of meaning. I find out what I mean in the making by testing my intentions against responses. It may seem counterintuitive, but my poetics is radically anti-solipsistic. Some people regard difficult-to-grasp poetry like mine as rooted in a private language and meant to be hermetic, abstract, or ungraspable. But I have been deeply affected by Wittgenstein’s aversion to “private” language and tend to think that the contained lyric of confessional and post-confessional poetry hangs on that more than, well, the kinds of poetry I want.

I am grateful to Bartczak for bringing me back to these issues of intention. In Kinds, I discuss the problem of lyric containment, but I might better have framed the problems as the containment of intention: the insistence on the poem’s meaning something specific, even thematic, over and against meaning as something that comes in response to a field of possibilities. Bartczak contrasts my anti-programmatic poetics with intentionalist theory, noting that I resist the “monolithic identity of meaning and intention.” Andrew Levy echoes this in his meditation on difficulty: “Poetry can be the making of an analogy for something non-linguistic and incomprehensible… good poems are incomprehensible.” Both frame my work as creating fields of possibility rather than discrete packets of meaning.

Intention here is like “plot” in David Antin’s sense rather than “narrative,” which necessarily involves transformation (as I discuss in the essay that is Andrew Levy’s focus, “UP Against Storytelling”). Levy reads that piece as a “meta-poem” resisting closure, noting that my “emphasis is on the ‘critical’ aspects of the ‘creative’ act’” and that its “play of subjects” is a refusal of the point. The intention of narrative is not the same as the intention of plot. By “lyric containment,” I mean poetry valued as plot (in the guise of utterance) and phobic to narrative transformation as a violation of the principles of intention. I want a poetry that builds in transformation: that is to say, something happens in the act of the poem that goes beyond rationalized intention but falls within the realm of intuition and aesthetic intelligence. It is not rational but part of reason (to use a Cavellian distinction).

My debt to Cavell is partly for his exorcism of skepticism, the idea that my thoughts are impenetrable to another or vice versa. And for his insistence that you know something not by “ocular proof” (a Cavellian echo –– from his essay “Othello and the Stake of the Other”–in the title of the first work Kinds) but by doing, responding, and acknowledging.

That’s why I can sometimes appear to be fighting for meaning, resisting the idea that everything goes and that there is no meaning. Mark Wallace comments on this adversarial dimension, likening my stance to Muhammad Ali’s “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee,” noting Kind’s “sheer amount of fighting” against institutional norms. Andrew Levy similarly observes my polemical energy. And Michael Davidson rightly focusses on my staging of aggrievement as a three-edged sword (that third edge is the killer). It comes down to not letting go or giving up. Drive he sd. I hate feeling that I have to intervene, but not as much as if I don’t. Yet, as Davidson underscores, I don’t shy away from the grief that comes with the zero-sum game of aggrievement.

(I admire Ali’s [Cassius Clay’s] 1963 spoken word album I Am the Greatest, primarily written by Jewish comedian Gary Belkin, who also wrote for Sid Caesar and Danny Kaye.)

I resist the term “experimental” if it suggests I don’t know what I am doing. In an odd twist, Stephanie Burt and I had an exchange in 2014 on the experimental, in which we switched roles: I argued against it from the point of view of knowhow and invention; she argued for it, but defined it as a controlled lab-coat microtinkering with small modulations of utterly conventional poems, as perhaps adding a syllable to fixed meter (https://asylum.short.gy/sb-cb). Even so, “experimental” is the term of art for just the kind of poetry Burt doesn’t want (with an occasional exception); that is, for the kind of poetry that rejects closure (to use Hejinian’s term) and is open to uncontrolled swerving (Lucretius, as Mark Wallace tags, is crucial).

As I was writing this, the Peruvian poet Mauricio Medo pressed me to push back against my rejection of “experimental” in an earlier conversation we had, collected in The Poetry of Idiomatic Insistence, asking if I agree with him that we are seeing, in effect, too little poetry of extravagant imagination, imagination that dwells, as Thoreau knew, in vagrancy. If experimental means rhetorical, performative, dynamic—an essay or try—and if its model is William Carlos Williams’s Spring and All … well then … To stop experimenting is to stop thinking, to become a shell of what you are, to become artificial intelligence. I am for the artifice of intelligence and the intelligence of artifice.

Elin Käck’s essay sharpens this point: she argues that Kinds — and my work overall—are not random trials but “provisional exhibitions,” curated constellations inviting permutation and reframing. Her emphasis on “frame” and “constellation” clarifies what I mean by experiment: not accident, but deliberate recontextualization, a movement among forms that generates new possibilities. Käck rightly links this lineage to Williams’s capaciousness, noting that my work extends the radical expansion of the poetry book into a multi-genre installation. To experiment, in this sense, is to keep language alive, to resist the calcification of thought.

Every day, I read or see a work of art that exceeds what I thought possible: some old, some new, some ordinary, and some out of bounds. And yet, and still, most (though not all) officially commended poetry and criticism is absorbed in the laborious task of containing thinking, deforesting the wilderness of thought, reining in language as if it were a bucking bronco (which, after all, it is). Forgive my mixed metaphors, but a mixed metaphor is better than a compliant simile.

As Michael Davidson observes, mine is a poetics of counterfactuals, process, and subversion through comedy. He links this to my discussion of Groucho Marx’s anarchic (“free thinking”) humor and Jewish traditions of resistance and cosmopolitanism, noting how I work celebrates rootlessness and neurodiversity. Davidson’s emphasis on “cripistemology” and the ethics of the erratic, as in his most recent book, Distressing Language: Disability and the Poetics of Error, has transformed my poetics. “Cripistemology”— knowledge derived from disability experience— is hardwired into poetic errancy. In his work, Davidson shows how neurodiverse poets, including those with dyslexia or dyspraxia, generate alternative modes of sense-making that resist normative literary expectations. So, one more time: these are not “experiments” in the narrow sense but cognitive registers. In this light, my own verbal pratfalls and linguistic inversions – my Groucho Marxisms –– are not defects but generative disruptions, part of a poetics that privileges error as insight, if one can say – topsy-turvy – privilege for what is stigmatized.

Bob Perelman highlights how my poetics détourn the expectation of tonal consistency and thematic closure, favoring an often dizzying interplay of voices and forms. He is generous in noting that I am not rejecting coherence but rather allowing meaning to emerge through engagement (what David Antin calls “radical coherence”). He values my refusal of seamless transitions as a challenge to an aesthetic conformity, where received modes of coherence are mistaken for value. Still, he gives a useful historical bounce to my comedic motif; for example, citing my opening epigraph of Lyly’s Anatomy of Wit (1578) where one Philautus responds to the eponymous Euphues in a mannered style of rhetorical embroidery—so laden with antithesis, alliteration, digression, parallelism, periphrasis, sound patterning, and outlandish allusion—that Euphues admits, as perhaps my readers might, he cannot grasp the argument and therefore cannot respond. But then Lyly paints both these characters as performance artists. Perelman’s sly implication is that flaunting what others perceive as a flaw does not extricate you from its grip.

Al Filreis, in his essay on “#CageFreePoetry,” underscores this unruliness: “Poetry constructed of verse sentences set free from their cages will always itself be a challenge to the cage.” My lab coat is my erring ear. If I were to say that much of what comes to my attention follows the straight path over the crooked and that its creators abhor those who don’t share their pride in right-thinking—what they may call “community” or even “politics”—then it would be right to say, “Hey!, old man!, the problem is you, that you fail to recognize the work we are doing, even when right in front of you: fail to see our struggle, our successes, our failures.” Andrew Levy is right that no matter how overblown my references are in this volume, they necessarily leave out more than they acknowledge, and that omission is exclusion. But I also think of Al Jolson’s line midway in his act: “Wait a minute, wait a minute. You ain’t heard nothin’ yet!” (Likely the first bit of spoken language in a talkie.) “What about all this writing?” as Käck quotes Williams. With Levy’s example of the “thickest” book, he ruefully notes that you can’t be comprehensively comprehensive. The absence of closure is not the closure of absence.

I know there are live wires out there. But the danger is that if those live wires don’t connect, there will be no sparks and no circulation. It’s the lack of any critical constellation—through periodicals or poetics or criticism—that I feel most acutely. It’s also in the middle of a disintegrating culture in the U.S., where much of the resistance seems to play out the roles the tyrants assign.

Too many poets are afraid of their own shadows, not realizing that the poetry is all shadows. But they are right to be scared: a shadow is part of the dark world. To follow the poem’s destination rather than your own, you lose traction in the world of peers and family and country, becoming outcast even to yourself. The sanity that poetry can produce drives others mad. The poets I admire are not mad, but they make others mad.

There has been a history of aesthetic invention in the US, perhaps, to let my rhetoric take over, starting with Poe (as Davidson notes). At various times, poets have come together less as schools than in negative solidarity: sharing a common opposition to the suffocating forces of virtue and conformism often iconized as craft. Such poetry, in its aversion of convention, opens meanings rather than nailing them down. The kinds of poetry I want signals not virtue but the unknown. And yes, to be sure, there have always been multiple, conflicting fronts, forming up out of egregious exclusions of each provisional formation.

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, journals, movements, and organizations have supported such new possibilities for poetry. However, right now, the distinction between mainstream and alternative is often viewed with disdain. A cynical attack on the so-called avant-garde as insufficiently “diverse” –– cynical not because it’s false, but because it’s no truer of such projected poetry groupings than it is of the mainstream. American poetry does need to be more diverse, but that includes aesthetic and language diversity; otherwise, the claim of diversity is a shell game; though I’ll always side with the shells. There is a righteous anger that marginalized poets should have done better than the prize-culture poets or, indeed, the larger culture, high and low. I share that anger. However, such marginalized and discombobulating poets are held to moral standards that they never claimed nor could plausibly have attained. So, the debunking began, but it is hardly new. Poe would have recognized it as the revenge of the mediocracy. Davidson recognizes the pitfalls of aggrievement.

Previously, “experimental” centers are now indistinguishable from their prize-oriented, “workshopping” counterparts. Places I once considered home now turn me away. Mark Wallace’s riff on “disappointment” is a needed rejoinder: Maybe the problem is my expectations. For most readers, critics, and poets, poetry is more about staying in line than “regaining unconsciousness,” as Harryette Mullen puts it. Yet through it all, individual poets continue to find ways to swerve –– and in so doing connect in subterranean ways.

To extend what I said moments ago, it may also be true that the U.S. is no longer as significant for new poetry because of its fervent parochialism. If poetry does not contribute to aesthetics, then it becomes another self-obsessed nationalist endeavor, similar to the standard cultural product all over the world.

Al Filreis, in his new book The Classroom & the Crowd, extends the rejection of closure beyond the reader and into the classroom. His book celebrates collective, nonspecialized, learner-centered reading as the necessary extension of a poetics of open possibilities and democratic vistas (echoing Whitman). So, it is unsurprising that he takes up my essay on taste, “#CageFreePoetry,” which argues for an expanded field of intention. As Filreis writes, “Poetry constructed of verse sentences set free from their cages will always itself be a challenge to the cage”—a principle he adapts to pedagogy by making the classroom a site of “wild nights” (echoing Dickinson) –– of interpretive freedom rather than deference to interpretive closure as authorized by hermeneutic expertise.

For Filreis and me, aesthetic judgment is crucial because it is not fixed, immutable, or transcendental. And, as Davidson points out, the “want” in my book title is a measure of desire rather than disinterested valuation; my desires are not “experimental” but are rooted in my body and psycho-social being, so that they are not the same as others, but the difference is what is common. The democratic space of poetry has to do with rubbing our tastes up against one another, not coming to agreements. Indeed, a value of a poem may be that it provokes sharp disagreements in judgment rather than the “assent” valued in official verse culture. Those incommensurable judgments allow the poem’s meaning not to be determined but to gel in/as process. If I say a poem is an act, not an intention, that’s because, as Filreis insists, I am less centered on saying than on doing, echoing Dewey and Austin but also Sondheim (“everybody says don’t / well I say do”). Acts are the three grand sections of the book; perhaps there is also an echo of the first century C.E. book of Acts, where “acts” stands for praxis. Käck mentions Goffman in this context: Interaction Rituals. She’s right to flag my incessant frame swaps from what I ought to say to what I do say. And sometimes the most powerful do is to do not.

Filreis and my credo is not quite, “If God does not exist, everything is permitted” (Ivan Karamazov). Interpretive openness does not mean abandoning critical intelligence but embracing dictions of differences. From a pedagogical point of view, judgment is not a matter of assent to a master narrative but acknowledging the qualities of a work are as open to dissensus as consensus.

Permit me a final divagination from the protocols of response. I want to bring in Paul Bové’s recent “Critical Poetic Grace” since it offers another caution to my emphasis on response (https://asylum.short.gy/bove). Truth is not found in “the hell of conversation” if conversation means consensus, but instead in disfluency, dissidence, and the “plentitude” of sound and sense that grace allows.

<button onclick=”openPopup”>

You said it! That’s right! The secret word for the day is disfluency.

</button>

We always quote Whitman: new poetry needs new readers, though he doesn’t quite say that. In “Ventures, On an Old Theme” (1892), he says: “To have great poets, there must be great audiences, too.” As in other forms of innovation, readers hooked on one experience of poetry may be the most resistant to a paradigm shift – even one that occurred well over a century ago. So, the work of poetry is to create (not simply find or confirm) those new audients –– and to support the poets creating this new work.

But now here’s Whitman in the “Preface” to the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass:

The messages of great poets to each man and woman are, Come to us on equal terms, Only then can you understand us, We are no better than you, What we enclose you enclose, What we enjoy you may enjoy. Did you suppose there could be only one Supreme? We affirm there can be unnumbered Supremes, and that one does not countervail another any more than one eyesight countervails another . . . The American bards shall be marked for generosity and affection and for encouraging competitors . . . They shall be kosmos . . without monopoly or secrecy . . glad to pass any thing to any one . . hungry for equals night and day.