This text is part of a b2o Review dossier on Charles Bernstein’s The Kinds of Poetry I Want.

“Float like a Butterfly, Sting like a Bee”: 95 Conversations with Charles Bernstein

Mark Wallace

1/ Charles, your essays frequently highlight the importance of conversation: “I only know what I think when I am in conversation. Conversation’s an art: my thinking comes alive in dialogue… I don’t have doctrines or positions, I have modes of engagement, situational rejoinders, reaction deformations…. Dialogue’s the center of what I do” (“Groucho and Me,” 41). Poetics thought of in such a way becomes a relationship, a dynamic, an involvement both with oneself and others that’s always available for revision and rewriting. Sometimes that involvement with others is also what writers need to find their way out of: “The kind of poetry I want is as averse to expression of solidarity and community as it is to univocal self-identity” (“The Body of the Poem,” 13). But obviously, an involvement that one wants out of is still an involvement.

2/ In recent years, when I begin reading one of your essays (my responses to your books of poems are different), I often think, “I’ve heard this before.” And that’s not surprising. Both your writing and your teaching (and the connections between the two) were essential elements of my Ph.D. education at SUNY Buffalo between your arrival there in 1989 and when I finished my degree in 1994. Of course there are always new details, new wrinkles, additional elements, but the basic framework, with concepts that may be phrased differently at different times, like “aesthetic justice,” and the body of writers to which you most frequently refer, are familiar to me (“The Body of the Poem,” 11). And yet, curiously, I find while reading that I feel startled by remembering just how familiar these things are. Your ideas, and the process of thinking through them that happens in your essays, have gone into my consciousness, and under it.

Your essays remind me especially of conversations that took place when I was a student in your classes. Reading your work brings me back to my own past, to how many of your ideas regarding poetics are foundational ideas for the work in literature that I’ve been doing in the years since. The question for me is what I’m going to do when I recognize the significance of your work on mine. What’s my role in this conversation between us?

3/ A thought is a form of motion, and it’s impossible not to move. Even if you stay mostly where you were, the ground that you stay on changes anyway, as the world around also alters itself. While other writers’ essays often tell me their conclusions, yours more frequently show the motion of your ideas, how they don’t stay still. Your essays seem like responses not just to changing conditions but to the condition of change. Interactions. Questions. Avoidances. Refusals. Conversations.

4/ “Where am I going to go with this?” is a question I find myself asking in response to the movement that goes on in your essays.

5/ Avoiding “doctrines and positions” or not, there remains a lot of fight in your essays, a struggle against the status quo, against institutional norms and institutionally powerful opinions, against overly assertive certainties coming from nearly every corner of the literary world. An arguing back against various points of view, especially those that want to limit aesthetic possibility. Sometimes the arguing back is direct, sometimes indirect. In your phrasing I sense echoes of Muhammad Ali: “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.”

In fact, one of the things I find notable in The Kinds of Poetry I Want is how much fighting it involves. It’s not that I didn’t expect this exactly, it’s the sheer amount of it over the course of the book. That’s not a criticism of the essays, but instead a recognition of the contexts in which they came into being, one in which avant garde and other experimental literary practices were routinely rejected by most, nearly all, of the most prominent and institutionally powerful poets and literary critics in the U.S. during the now over-fifty years that your work has been appearing in print.

Some of these essays, especially ones like “Stein Stein Stein” and “Summa Contra Gentiles,” are organized like catalogues of your conflicts with others. Some of the most distressing conflicts (to me anyway, and maybe to you?) are those with writers and scholars who might be in other contexts mostly in agreement with your point of view, like Barrett Watten (“Summa Contra Gentiles,” 317-318).

It’s no wonder that you have to mention (and more than once) that, physically, “I’ve never hit anyone” (“Summa Contra Gentiles,” 293). It’s like a necessary disclaimer: No writers were physically assaulted during the making of this poetics.

6/ The Poetics List (1993-2014) you founded at SUNY Buffalo was a forum in which many conversations often became something like verbal boxing matches, although that was hardly the only kind of dynamic in play on a forum designed around the possibility of conversation. On at least one occasion that a lot of people remember, a writer threatened to punch another writer. Of course we both know how gendered male the verbal boxing match over poetics is.

Although there is also, to state the obvious, a lot of fight in women poets too.

7/ Despite my sense of familiarity, I always find something new in a new book of your essays, even a book like The Kinds of Poetry I Want, which collects essays written over a long period of time, quite a few of which I’ve read before. Beyond classroom discussions of Louis Zukovsky and Bernadette Mayer that led us to Catullus, I don’t recall much conversation about Roman poetry in my time working with you at SUNY Buffalo. But there it is in The Kinds of Poetry I Want, an essay built partly around translations of Lucretius, especially what he tried to say about what could not be seen, could not be counted on, did not fit with people’s perceptions of the world: “A central problem for Lucretius was how to articulate a view of the world that is aversive to (that swerves from) what is visible, that seems to push against what intuitively seems to be the case” (“The Swerve of Verse,” 112). What is the importance of the exception to the rule? Of that which doesn’t fit our assumptions? Of the thing or moment that doesn’t conform to our predefined categories or ideas? Of the things we can’t see because they don’t fit the way we’ve been trained to see?

8/ Conversation has been central to my own poetics, as well as a key part of my fiction, in which dialogues are often where the action is. An interest in literary dialogue began for me before I was acquainted with your work. When I was an M.A. student at SUNY Binghamton from 1986-88, I co-authored, along with my friends Joseph Battaglia and Keith Eckert, a small set of chapbooks of multiple-author poems (rengas and variations on that concept) influenced by the book Renga: A Chain of Poems (1971), with an introduction by Octavio Paz and co-authored by him, Jacques Roubaud, Eduardo Sanguinetti, and Charles Tomlinson. One of the things I liked about poems from the time I began writing them seriously was the immediacy of interaction possible in a multi-author text. A line of poetry bounces off other lines, off other people, off problems in poetry and problems beyond poetry.

8/ The notion of a poem or a literary press as a conversation played a central role in the group publication projects I worked on while a Ph.D. student in the years I was studying with you. Leave Books was initially a chapbook press that the graduate student co-editors (Juliana Sphar, myself, Brigham Taylor, and later Kristin Prevallet and Pam Rehm) believed was a way of creating a dynamic interaction of voices. Poetic Briefs, edited by Elizabeth Burns and Jefferson Hansen in graduate school and afterwards, a publication to which I often contributed, frequently used the format of the conversation for its explorations in poetics. The one publication project from that time of which I was sole editor, the small poetry magazine Situation, was based on the idea of poetry as an interaction (that is, a conversation) with the materiality of the world. All these publications (and others came later) were funded wholly or in part by the Buffalo Poetics Program. You and other faculty in the program encouraged students to engage in conversation both in class and in publication. To rephrase Gertrude Stein, “the conversation was spreading.” As it did, and does.

9/ A key sign of one’s work having an effect on the world is that others pick it up and do something with it, move it with them somewhere. That doesn’t happen for every writer. Sometimes it doesn’t happen at all, or for a long time. Even excellent writers can be forgotten. But from early in your literary work, it seems, you have been creating or helping to create conversations between writers.

10/ In the academic context, quoting and citing authors is fundamental to making a work recognizable as criticism or scholarship. At its best, quotation becomes a way of continuing important conversations. At worst it becomes a marker of acceptance of conventional academic authority (with its potential access to the resources that such authority might offer), as you have often pointed out: “Professionalized scholarly writing often seems to play off a list of master-theorists who must be cited, even if the subject is overcoming mastery” (“95 Theses,” 15).

11/ In the last two decades I have not devoted much time to in-depth scholarly or critical writing. While remaining engaged with reading such writing, when I have time, I’ve found myself more engaged with the possibilities of poetry and fiction writing. And I’ve also found myself frustrated with how the dynamics of authority and access to resources operate on the way one is allowed to write an essay for publication in academic journals. I still love to write reviews of books. Most of them I simply publish on my blog.

12/ Certainly, poetry and fiction aren’t free of problems of authority and power. Yet I myself find in them a broader range of possibility than in academic writing. I might once have cared too much (why “too much”? do I mean “more than I wish I did”?) whether my essays would be academically acceptable. This is an issue many people who want to work in the academic context have to face. Maybe caring more than I wish I did about what is academically acceptable is one of the reasons I moved away from writing criticism and poetics, although of course there are many publications not directly connected to academia that will publish essays on poetics.

13/ An essential element of the conventional academic essay is that it focuses on a single main argument. In the usual hypotactic structure of argument, there is a main argument, and then there are secondary arguments that are subsets of the main argument. In contrast, many of your essays in The Kinds of Poetry I Want and elsewhere are what I might call “list arguments,” or more exactly, a list of different conversations, some of which might not even qualify as “arguments” (what makes something qualify as “argument”?). Maybe the term “list essay” is more accurate. A list is not inherently paratactical, since concerns are likely to reoccur. But the implications of its form are more paratactical than hypotactical.

14/ At first, while reading around in The Kinds of Poetry I Want, I’m not able to see how my loosely scattered responses to the book will add up to an “argument.” But one list essay especially catches my attention: “95 Theses.” Reading that essay helps me figure out how I will write an essay on your book.

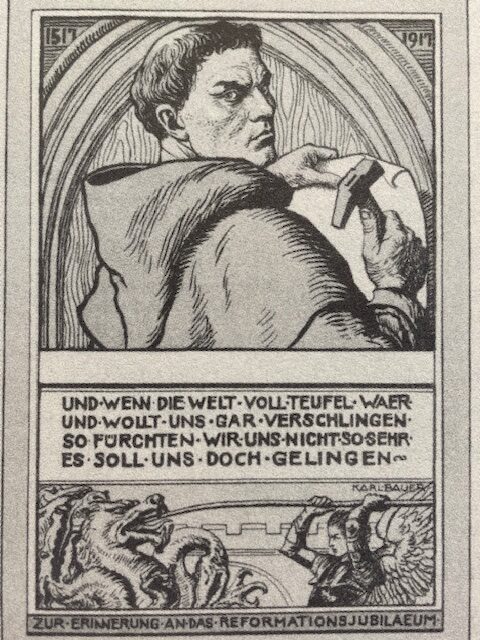

Martin Luther’s work titled “95 Theses,” published in 1517, stated the specific ways he wanted to break with the ideas and corrupt practices of the Catholic Church, a stance which reminds me of your own attitudes regarding the practices of the academic and literary professions. Luther wanted to redefine the religious tradition he had inherited. Seeing the title of your essay made me think of my father, a longtime historian of European and American Protestantism, who died in February 2021, and who often talked to me about Martin Luther.

Thinking of my father in this context reminded me of a brief conversation you and I had about my father, regarding something he once said to me: “I was halfway through writing my second book before it occurred to me that how I wrote a book was important.” As a historian, he wanted to get information and theories across to readers, but he found himself, unexpectedly, confronting both rhetoric and aesthetics. It’s possible to write a book without thinking much about aesthetics. It’s even common. It’s even common among people writing poems. People learn that poems are written a certain way and then they write them that way, without much questioning of “Why is this what a poem should be like?” Art and literature without a conscious exploration and questioning of its own aesthetics.

I can’t say that I think my father ever became an impressive stylist. But at least his prose became more energetic.

15/ You write, “I like to think the relation of one work to the next in one of my books is comparable to the twisting, inside-out movement of a Möbius strip” (“Offbeat,” 27). To the extent that metaphors (comparisons between things) can provide good descriptions (imperfectly but revealingly), I think this metaphor works well.

The idea of the Möbius strip reminds me of a conversation I’ve often had with you (or more accurately never with you, but with myself about your work) in relation to the concept of the poet-critic. To a greater extent than any contemporary I can immediately think of, your work blends the two roles, with every poem nearly an essay / work of criticism, and every essay nearly a poem. Disjointedness between the structures and goals of the two is inevitable, of course, and the slippages between them appear differently in different of your works. But there’s a more consistent drive to mingle the poem and the essay in your work than in the work of other contemporary poet-critics I can think of.

16/ Without active questioning, whatever one is doing slips back towards the conventional, the accepted, the conservative in the sense of I take it on faith (often without even knowing that I’m taking it on faith) that this is how it’s done. Towards accepting the world we have received. Which is one of the things that Martin Luther was criticizing about the Catholic Church, along with the decay and corruption that had crept into the Church because of its failure to examine the relationship between belief and action. As Luther realized, it can be a big mistake to take your own religion on faith.

17/ I think of Robert Creeley saying, “Sometimes I just want to sit in a chair and be there.” I heard him say this in person once. I don’t know if he ever said it in print. The desire to find a stable place from which one doesn’t have to question the world or one’s role in it can be very powerful. In my story collection Walking Dreams there’s a story called “Design For A Chair Not A Chair” that concerns the construction and destruction of chairs and of people’s lives. We might want to sit down and be there, but the chair we’re sitting in is part of history, and history is written in language… and so are we. We don’t become one with things but can only express and enact perspectives towards them. Of course, the ur-text now for all chairs of this kind is a pipe in an artwork by René Magritte: the exemplary text we’re bound to reference when we realize that when we try to understand and connect with the things of this world, we often end up among our own drawings and words.

18/ Speaking of Robert Creeley, one result of the fact that it’s (some of) my own education at stake when I’m reading your essays is that reading something you have written often throws me back into specific conversations I was part of as a student. In “Shadows” you discuss a conversation involving Robert Creeley that took place in a graduate seminar (59). I was a student in that seminar, and I was there that day. As these things tend to go, I remember another part of the conversation than the one recounted in your essay.

The class was taking place in the big seminar room that was also, if I recall correctly, partly your office as David Gray Chair of Poetry and Letters. It had a long row of windows and was on one of the top floors of the building. The day was cold, there was snow on the ground, and it was cloudy, maybe not snowing at the moment but sure to be snowing again soon, as is often true in Buffalo. There was another university building of similar height not far away. When a student claimed to be disappointed by Creeley’s response to a question, and either before or after (I think before) Creeley claimed that he was disappointed too, Creeley pointed out the window. On the roof of that opposite building, in the cold, standing in the snow, was a university maintenance worker leaning over something (I remember this clearly) then straightening up again. “How do you think he feels?” Creeley said.

The point seemed to me about labor, about class, about the nature of disappointment and how it was parcelled out to others. About (in a terminology I don’t remember using then but is common now) privilege. Leaving aside that some of us in the room, whether before or later, might have done maintenance work ourselves, for the moment at least we were indoors, discussing poetics among a group of ambitious and contentious people in a way that might lead to possible opportunities for us. It was only other people who had the responsibility right then of keeping us warm and dry in the building during our discussion.

19/ Oh, disappointment. The feeling that we have gotten less than we wanted or (more full of ourselves) than we deserved. How do we handle our own disappointment (and with writers there’s a lot of it) or the disappointment of others (and there’s a lot of it). Is there anything poetics can do about it? Will a conversation about it with others help? Even if we share our disappointments?

20/ Where do we get our thoughts from? From ourselves and other people. Which ones do we go on thinking, and which do we try to get rid of or change? People converse with others. People converse with themselves. I try to think of what language would be without conversation and I find I can’t imagine it. If sometimes we need words for ourselves alone, certainly most of the reason we need words involves the reality of others, that we don’t know what they’re thinking or feeling unless they talk with us.

21/ Of course there won’t be 95 conversations in this essay, just like there aren’t 95 theses in your essay with that name. I never intended that there would be. But the fact is, there easily could be. The conversations we have in our heads with others are ongoing and continue until we reach that point when there are no conversations in our heads anymore. There is always space available for them: “64. The rest of these 95 theses intentionally left blank” (“95 Theses,” 19).

23/ “Nearly touching are the ethical realm of our obligation to others and the aesthetic world of our freedom from such obligations” (“Offbeat,” 26). This line alone seems to me more valuable than many whole books of poetics have been. It raises and then answers a question I hear poets and critics wrestle with endlessly, often without satisfying answers. The way it’s more usually discussed: If my poems carry with them an ethical responsibility to others, doesn’t the way I write them also carry that responsibility, in that I have to write in a way that will foreground and make legible to those same others the ethical responsibility I have towards them? Doesn’t my responsibility to them require that I write in a way they can accept and understand?

23 bis/ But if I am required to limit what I must write about, and the way I must write it, because of what others want it to be, doesn’t that mean I may not be able to write it ethically? If the structures I might need or want to write in, and the content I might need to write, are constrained by what others are supposedly demanding of me before they give me permission to write, might the requirement that I receive their permission become exactly the block that prevents me from achieving what I’m trying to? That would not be ethical. That would be a world of language (and people) in chains. Which is too often exactly what we have.

24/ What if writing ethically sometimes requires that I refuse to write in a way I have been given permission to write? I think this question is part of what your point speaks to. Maybe what and how I write need to find their own way. If I take writing to be at least partly the discovery and development of my own relationship (in writing) to a given particular problem, don’t others have the responsibility to allow me the full range of freedom I might need to find how and what I want to say?

They do, of course. But that doesn’t mean they’ll behave responsibly.

25/ “There is no one sort of American poetry and certainly no right sort—this is what makes aesthetic invention so necessary” (“Offbeat,” 25).

Absolutely so, although much of your book points to the inevitable corollary: that the continued existence of new possibilities for what a poem might be depends on a writer considering what the ramifications of the subject matter, the aesthetics, and the relation between the two might become in a given work. It transfers the responsibility for the significance of the poem away from a predetermined standard of what that significance might be, because there is no outside authority that can give the writer certainty about what’s right or wrong. Decisions about aesthetics and ethics are part of what the poet has to think through, has to enact.

And of course your statement does not assert that all poems are by definition the right sort of poems. As you also say: “anything is possible but only a very few things get through that eye of a needle that separates charm from harm” (“#CageFreePoetry,” 162). Instead, whatever percentage of poems get through whatever critical needle eye is in question, many poems reveal difficulties and shortcomings in thinking through the problems connected to poetic invention, whether on the level of aesthetics or content or the relation between them.

What’s at stake in writing the way I’m writing? What’s at stake in speaking about this subject? Prior answers to these questions in prior poems do not provide enough help. They can provide guidance and example, but not certainty or an answer.

26/ The act of composition is the act of the radical risk inherent in the freedom (never absolute, because it is always constrained by what we can imagine and the circumstances in which we imagine them) of the moment of composition. Sometimes, a poem has to be dared into existence.

27/ In the face of the radical risk (offered and posed) by the moment of composition, I find a lot of the more conventional stances of the 20th century (and indeed the 21st) to rest on premises that feel so blatantly limited that I want to call them “prejudices.” And in fact if they were premises made about people, it would be much more obvious that they are prejudices.

28/ Consider the following lines from Charles Altieri that are part of your ongoing conversation with him:

“I will argue that only an explicit sense of purposive activity can fully engage the world in a way that addresses the density of our sense of the event-making poetic powers that have an impact on history, albeit usually local versions of history” (“Too Philosophical for a Poet,” 126).

“But the more poetry becomes an internal system, the more difficult it becomes to specify how it might affect life beyond the poem” (“Too Philosophical for a Poet,” 127).

What seems to me remarkable about Altieri’s points is his assertion that only some kinds of poems, written in some kinds of ways, can have an “impact on history.” He suggests that if a poem “becomes an internal system,” by which I think he means one that does not explicitly present its “system” to readers, then it becomes harder to “specify how it might affect life beyond the poem.” But what is the “system” of a poem? The philosophy that it explains as well as embodies? Is the “system” of it something other than itself? Some part of itself but not the whole of itself?

29/ Surely the life that a poem has beyond itself is not determined by itself, but by what others in conversation with it make of it, whatever or however the poem might say what it says.

30/ And surely it’s often not possible for anyone to specify exactly how a poem might affect, or did affect, other people and situations. It could be in some cases an appropriate question for a historian or literary scholar. Even if understood historically, much of the effect a poem has on life is found in the reactions of the people who respond to it, and most of those reactions are undoubtedly lost to time. Perhaps Altieri means “historical effects that can be documented”?

31/ Altieri seems to want a poem that will speak to history in the right way. Which is what? A poem that is “Addressing the density of our sense of the event-making poetic powers.” Whose density? Whose sense? Which particular poetic powers are “event-making”?

Whatever his answers to those questions might be, poems that speak to history in “wrong ways” (which would be what?) also make history. Given what history is, surely poems that speak in “wrong ways” have often made more history than poems that speak in “right” ones. I think for instance of Rudyard Kipling’s “The White Man’s Burden” (1899) and the racism and sexism involved in believing that only white men can make the world sane and rational, and in promoting a colonizing project of the Philippines as an attempt to achieve that end. Or the poems of Rupert Brooke, which promoted a romantic view of WWI which was widely believed in England, a war in which he was soon killed. Both Kipling and Brooke wrote immensely popular poems that reflected and influenced people and history for generations.

32/ It seems then that lurking in Altieri’s terms, many of which are hard to pin down, is an idea that only one kind of poem is the right kind of poem for affecting history.

33/ “There is only one kind of person that is the right kind of person for affecting history.” Leaving aside that it’s quite possible for someone to say that, when applied to a person it nonetheless feels more transparently absurd and, dare I say, prejudiced.

34/ Are persons, then, more complex than poems? Do poems need to be simpler than people in order to find the right way to be effective? Isn’t it more likely that, given that a poem is often a highly developed example of what a person can do with a language, that what we can do with language in a poem is, if not complex in the exact way that people are complex, at least contrastingly complex? Complex along parallel lines that sometimes meet and sometimes wander away from each other.

35/ I wonder why it is that people, and often the very smart and informed and sensitive people who read poems, often try to reduce poems to one main goal, and often a very simple goal. Your writing is nearly constantly fighting back against this problem. I think of the more common rhetorical frameworks I hear now: 1) A poem must have heart, must speak to the emotions of readers. 2) A poem must have a politics that speaks to the facts of injustice and inequality. There’s a third, though its profile is lower: 3) A poem must try to do something different than has been done before. This can be an issue either of aesthetics or subject matter or both.

36/ One thing that I like about your focus on aesthetics is that it doesn’t necessarily foreclose on the possibilities of emotions or politics. Instead, it allows poems to explore emotions or politics from new angles. So why is it that, so often, those insisting on a focus on emotions or politics demand foreclosure on the possibilities of aesthetics? And certainly, there have been some arguments in avant garde theorizing which suggest that some subject matters, such as “the personal,” are irrelevant.

Why can’t a poem speak of emotions and politics, or use aesthetics, differently than other poems, or explore them differently, or even sometimes avoid (some of) them? Why can’t they all be considered relevant elements of poems without having to state unequivocally that one must dominate the others?

37/ It occurs to me that people who care about poetry are often as concerned about controlling what people might become as they are about controlling what poems might become. And there are certainly important reasons for that, given what people are capable of, however unlikely it is that any such instance of controlling will succeed.

38/ And probably we should be at least as concerned about what people and poems have been until now.

39/ Perhaps the measure of poetry’s humanness, and relevance to the human, but equally its measure of resistance to the human, resistance to any single instance of treatment or understanding, is that poetry will always be more, and more various, than the kinds of poetry that you or I or anyone might want: want poetry to be, or want of or from it. Poetry retains in that uncontainable abundance a mystery that stands at a distance from us, a space for uncertainty that goes beyond any of our all-too-human intentions.

References

Bernstein, Charles. 2024. The Kinds of Poetry I Want: Essays and Comedies. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.