This text is part of a b2o Review dossier on Charles Bernstein’s The Kinds of Poetry I Want.

Groucho Marxism: Charles Bernstein’s Kinds of Poetry

Michael Davidson

“I am for avant-garde comedy and stand-up poetry” (350)[1]

“Am I just a voice crying in the wilderness, or am I a just voice pleading aggrievement?” (163)

The Secret Word

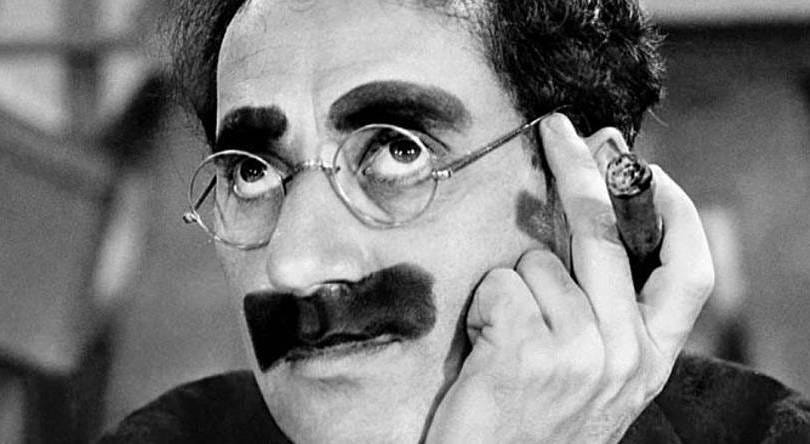

In the opening of the 1950s quiz show, You Bet Your Life, the MC, George Fenneman would introduce Groucho Marx: “And here he is, the one, the only…”–leaving a blank for the audience to shout: “GROUCHO!”–followed by the theme song, “Hooray for Captain Spaulding.” Groucho, cigar in hand, would then display the “secret word” for the day which, if one of the contestants said it, would drop down from the ceiling, attached to a duck with a cigar (on one occasion, the duck was replaced by Harpo and on another, by Mamie Van Doran), and Groucho would hand the lucky winner $25.00 (later this amount was increased to $100.00). Fenneman would introduce our two guests for today’s quiz and step off stage, leaving the floor open for Groucho’s witty, often acerbic, repartee with the couple. As for the duck falling from the ceiling, these were the halcyon days of early television when the medium was figuring out how far it could go, what visual tomfoolery one could get away with. Ernie Kovacs was the inventive impresario of the medium, Spike Jones was its resident composer, and comics like Cid Caesar, George Burns, Henny Youngman, Milton Berle and others exploited the physical limits of the black and white screen and the unpredictable qualities of a live audience. Groucho’s verbal wit and arch retorts were somewhat improvisational, but they also subverted the interview format by endless asides and miscues. Was this avant-garde comedy or stand-up poetry?

In Charles Bernstein’s terms, the secret word for today is “pataquerical,” a nonce formulation for his aesthetics that could easily apply to Groucho’s humor. What he calls the pataquerical is “a flickering zone of counterfactuals that allow for possibility, reflection, intensified sensation, and speculation” (11). In an earlier essay in The Pitch of Poetry, “The Pataquerical Imagination”, Bernstein finds one of its sources in Poe whose “Poetic Principle” expresses the scandalous belief that poetry “has no concern either with Duty or Truth” and that personal taste is superior to transcendent ideas” (Bernstein: 2016, 299). He also relates it to Marx’s critique in The German Ideology of young Hegelians for their belief in critique as a value for its own sake rather than as a dialectical process “that has no end point but like a Klein bottle doubles back on itself…” (Bernstein: 2016, 296). In its invocation of Alfred Jarry’s pataphysics, the pataquerical is a poetics of process, irresolution, and speculation and as a result cannot be confirmed by an appeal to “convention, accessibility, compromise, refinement, or humanist literary values,” qualities abundant in what he labels “Official Verse Culture” (OVC [296]). It is tempting to see the pataquerical as a version of what one interviewer calls Bernstein’s “Groucho Marxism,” his fusion of comedy and subversion, borsht belt humor and social critique. Against “aesthetic illiberalism” that neutralizes and normalizes, the pataquerical is like the duck, a “secret word” that drops down to interrupt the show and surprise the audience. Bernstein’s new book, The Kinds of Poetry I Want serves as a brief on the pataquerical in its multiple forms, both aesthetic and political.

The title and much of its imperative are taken from Hugh MacDiarmid’s 1961 book, The Kind of Poetry I Want, which advocates “A poetry that is—to use the terms of red dog–/ High, low, jack, and the goddamn game” (MacDiarmid qtd. 153). There’s plenty of the red dog in Bernstein’s poker hand–from Lucretius, Sartre, and Tao Te Ching (high) to Bob Dylan, Thelonious Monk, and Cid Caesar (low). And the variation on MacDiarmid’s title stresses the multiple “kinds” of poetry Charles wants, wanting itself being a value seldom mentioned in aesthetic discourse. Writings about poetic value that posit some universal standard or monadic formal closure are countered by a word for unfulfilled desire: the kinds of poems he wants are the kinds of poems he finds lacking.

The book is divided into three “acts,” each of which is subdivided into multiple “scenes” containing a wild mixture of genres: interviews, poems, homophonic translations, protestant letters, erasure texts, midrashic commentaries, concrete poems, and aphorisms. The range of genres is matched by the book’s heteroglossic display of idiolects—from broad-based comedy to stentorian jeremiad, from one-liners to flat-footed howlers, from scholarly analysis to cliché and bad puns. This variety reflects the venues in which earlier versions were published or given as talks. The lengthy interviews are among the most important statements of Bernstein’s poetics; his responses to questions from Vicki Hudspith, Thomas Fink, Braulio Paz, Andrew David King, Feng Yi and others give him a chance to elaborate on his favorite issues and incorporate often moving autobiographical information. He is a generous respondent, providing extended answers with attendant asides and detours that deflate some of the interviewers’ more ponderous questions. The book concludes with one of his most important essays, “Doubletalking the Homophonic Sublime,” that deals with the phenomenon of translations based on the sound of words rather than sense–from Zukofsky’s Catullus and David Melnick’s Men in Aida to his own collaborations with Leevi Lehto and Richard Tuttle. The tutelary genius of homophonic sublime is Cid Caesar whose doubletalking in nightclub routines involved a virtuoso highspeed imitation of various foreign languages, a routine that animates the essay’s opening remarks:

Never met a pun I didn’t like.

I’m a veritable Will Rogers, with plenty of roger but without the will to say enough’s enough already. All instinct. Like a Brooklyn Ahab stalking a whale in the backyard or a curmudgeonly Odysseus hurtling towards his sirens.

But wait a sec.

This is not the opening of a nightclub act. (349-50)

But in one sense the essay is a kind of nightclub act using homophony to provoke other kinds of associations beyond the auditory.

In keeping with the parodic qualities of Jarry’s pataphysics, Bernstein engages in a wide-range of speech genres—from mock-didactic oratory (“I come to you today at the 138th Annual Convention of the Modern Language Association…” [155]), literary prize announcements (“…no one can doubt that this work is one of the most ambitious books of poetry published in our time” [312]) and hyperbolic jargon in recommendation letters (“What distinguishes Danniello, and makes him such a strong candidate for admission to our doctoral English program, is his deep animosity to literature” [319]). Like Pope and Swift before him, Bernstein tilts at the canons of approved public discourse by mimicking their authorizing rhetoric. Idiolects are more than ventriloquized satire; they carry the weight of their institutional provenance, the authority of the professoriate, the publishing industry, the academic marketplace through which literary culture is formed and reinforced.

The Kinds resembles several of his previous collections, A Poetics, My Way, Attack of the Difficult Poem, The Pitch of Poetry, in its eclectic variety, but one through line is the work of Jewishness in an age of cultural cancellation and identity politics. He invokes T.S. Eliot’s infamous worry in After Strange Gods (1933) that “Reasons of race and religion combine to make any large number of free-thinking Jews undesirable” (Eliot qtd. 155). As a self-declared free-thinking Jew himself, Bernstein recuperates free-thinking for the kinds of poetry he wants—that of Gertrude Stein, Louis Zukofsky, Larry Eigner, Hannah Wiener, David Antin, Johanna Drucker, Jerome Rothenberg, not to mention the borscht belt comedians he invokes. At one point he modifies Charles Olson’s opening to his book on Melville, Call Me Ishmael, by saying, “I take RACE to be the central fact for those born in the Americas. I spell it large because it comes large here. Large and without mercy” (33). In a way the substitution of “race” for Melville’s “space” recognizes the degree to which American manifest destiny of expansion was authorized by the erasure, relocation, and marginalization of racial others—including Jews.

Which is not to say that Bernstein has not addressed Jewishness in previous works. Here, however, the theme is supported by his use of “midrashic antinomianism” that links Jewish rabbinical commentary with American Protestantism, or as Bernstein might say, Reb Ben Ezra meets Emily Dickinson (164). Both parts of the phrase stress the Word as an infinite possibility, unsettled in its meanings and tolerant of its misunderstandings. Midrashic antinomianism could apply equally to avant-garde writing or Jewish humor: “Groucho Marx’s jokes are allegories of escape and especially escape from being defined. The Jewish comic, like the Jewish poet, dodges, deflects, evades, ducks” (45). Bernstein devotes many passages in the book to his own relationship to secular Jewishness, growing up in an assimilated household, albeit, as he has said, with Jewish and Zionist identifications.[2] Antisemitism was prevalent in Bernstein’s early life at Harvard and became linked in his mind with more conservative literary traditions, often, ironically enough, traditions reinforced by Jewish academics and poets. In a lengthy letter to Paul Bové included in the book, Bernstein discusses Lional Trilling’s The Liberal Imagination as an example of cultural consensus among Jewish intellectuals of the cold war period who also “dodged, deflected, evaded and ducked” in order to assimilate. Trilling was not a Jewish neocon of the Commentary variety like Norman Podhoretz or Hilton Kramer, but he nevertheless embodied an “Arnoldian figure of a high culture where Jews might be heard if not seen as such“ (298). Thinking of Trilling’s student, Allen Ginsberg and his Columbia classmate, Louis Zukofsky, Bernstein sets up a contrast between the “illiberalism” of Jewish Cold War intellectuals and writers who confronted antisemitic headwinds by different means.

In The Kinds more radical strains in Jewish cultural traditions are linked to avant garde practices, but Bernstein realizes that experimental poetics itself has recently been attacked for its presumed racial exclusions. With events such as the Mongrel Coalition for Gringpo manifestos of 2015, Janet Malcolm’s attack on Gertrude Stein in the New Yorker, Dorothy Wang’s reconsideration of the “Poundian-Objectivist-New York School-Language-Conceptual tradition,” Juliana Spahr’s and Stephanie Young’s critique of the “white room” of academic writing programs, experimental writing is suddenly under the microscope for its whiteness and, in Malcolm’s case, Fascist complicity.[3] In Natalia Cecire’s terms, “Experimental writing is a white recovery project” (Cecire, 2019: 34). Implicit in these responses is the idea that formal experiment erases identity, both personal and cultural, and that its endeavor is purchased by silencing minority voices, histories, idioms. Kenneth Goldsmith’s conceptualist performance of Michael Brown’s medical autopsy would be the most notorious version of such practices and has been the object of numerous anti-racist critiques. Identity, as Bernstein acknowledges, “remains a volatile issue for the poetics of invention,” nowhere more evident than in antisemitic attacks:

Ezra Pound’s attack on Jews as rootless cosmopolitans echoes in today’s culture debates. The ahistorical/revanchist quest for a deep or authentic identity as the sole property of a single group, which has fueled the rise of the global right, is toxic for the kind of poetry I want. (39)

This toxicity, however divisive, fuels a good deal of the book’s tone of aggrievement (more on this later) and its attempt to understand the precarious status of Jewish writers as both outsiders (“rootless cosmopolitans”) and poetic innovators. Bernstein seeks to realign a politics of race and anti-racism with rootlessness as both a cultural and aesthetic value, not by advocating a revolution of the different but by bringing more of Groucho to the Marxian table.

Taste or What I Want

The pataquerical has an ethical component in its emphasis on the unfashionable, the mundane, the awkward, the banal. By exposing the all too familiar (and thus disparaged), Bernstein hopes to create an expanded field of knowledge against fixed and accepted standards. Poems that win prizes and appear in The New Yorker or New York Review of Books or that are taught in creative writing programs are, in terms Bernstein develops elsewhere, “absorptive,” drawing the reader into the poem, affirming what one already believes, while effacing the ideology and historicity of its production.[4] The agonized voice of Lowell or Plath gives way in the 1970s and 1980s to a more self-effacing voice, what Charles Altieri calls the “scenic mode”: “The task is not to transform the social but to make voice an index of how we can register the complexity of the given and thus develop our personal powers for responding to experience” (Altieri, 1984: 36). Official Verse Culture (OVC) is somewhat of a red herring today, however, since its confessionalist prototype is rather out of fashion. And more to the point, OVC now includes many of Bernstein’s friends and fellow poets who appear in those venues and teach in those programs. Perhaps mainstream poetry is a necessary fiction by which to measure the poetry one wants.

Bernstein asserts the positive value of taste in defining his poetics, and in this respect counters Kant’s privileging of aesthetic judgment and disinterestedness over taste by asserting his own will to choose. Kant says when we put something on a pedestal as beautiful, we presume that others must find it so (“the delight in an object is imputed to every one” [Kant: 1952, 53]). But if we speak of something being beautiful for me we judge based on interestedness and quotidian circumstance. In the aesthetic tradition from Kant and Baumgarten to Arnold, Eliot and the New Criticism, judgments based on personal taste are lesser forms of appreciation since they do not aspire to universal assent. But its minority position allows for greater freedom: “[Larry] Eigner may well be an acquired taste. But for the kind of aestheticism I want, all tastes are acquired. You feel it on the tongue before you prize it in the mind” (167). Here affect trumps reason; we taste pleasure before we digest it as pleasurable. There is a risk that in claiming personal taste as a value he engages in a specious form of aestheticism that argues for specificity as an end in itself. Occasionally that risk produces a kind of aesthetic nervousness: “Am I just a voice crying in the wilderness, or am I a just voice pleading aggrievement?” (163).

The term “aesthetic nervousness” is used by Ato Quayson to describe the encounter of an able-bodied person with someone with a disability. He explains that this encounter may be startling or uncomfortable, but it also instructs one about the body presumed to be normal. I’ve adapted Quayson’s term to describe the aesthetic nervousness deriving from an encounter with the “different text”–one that refuses absorption, veers in unpredictable directions, poaches on other idiolects and speech genres. The phrase also refers to Bernstein’s willed fence-straddling around his voice–whether a Cassandra or an Achilles. In both cases—the reader’s confrontation with the unsettling text or the poet’s ambivalence about the impact of their words—a kind of revelation is possible.

Disability theorists might call the knowledge gained by such a revelation as a form of “cripistemology,” how living with physical or cognitive difference produces alternate forms of knowledge, ways of seeing, hearing, thinking. Bernstein addresses this issue in his essay on the pataquerical in The Pitch of Poetry by referring to the work of disabled poets such as Jennifer Bartlett, Hannah Weiner, Jordan Scott, Amanda Baggs and others whose work is a direct outgrowth of neurological and developmental conditions. A cripistemological approach to their work is antithetical to what many people regard as triumphalist compensation where, because of a physical or cognitive limit, the poet “adapts” to another sensorium or medium. Rather, cripistemology describes a critical perspective on social norms and conventions derived from living in a different bodymind. Bernstein’s own perspective is formed by living with a form of cognitive dyslexia that impacts his spelling and word order and, beyond that, inspires his verbal wit:

Then again, the comedy I use is sometimes linguistic pratfalls: mistakes proliferate. That may be a way to cover my own cognitive dyspraxia, my tendency to invert words and letters and confuse left and right. Freud called such slips of the tongue parapraxis. And that’s another root of pataquerics (234)

For Freud “slips of the tongue” or parapraxes signal the eruption of repressed content, an unconscious substitution of a wrong word to cover a word with traumatic associations, often of a sexual nature. Dyslexia, however, is not about repressed sexual urges (Bernstein might beg to differ) but is a neurodevelopmental condition relating to language processing and the ability to form words and word sequences. His dyslexia is evident in poems like “Defence [sic] of Poetry,” a response to an essay by Brian McHale that deals, in part, with Bernstein’s work and whose academic prose is undermined by the poet’s dyslectic inversions:

My problem with deploying a term liek

nonelen

in these cases is acutually similar to

your

cirtique of the term ideopigical

unamlsing as a too-broad unanuajce

interprestive proacdeure. (Bernstein: 1999, 1)

I’ve discussed this poem elsewhere but see it as an instance of Bernstein’s displacement of reasoned discussion (a poet’s response to his critic) by neurodiverse means.[5] Its title invokes Shelley’s “Defense of Poetry” (also a response to a critic, Thomas Love Peacock) but its typographical errors, often based on McHale’s language, transform a speech or writing “defect” into a generative repurposing of the critic’s language. In his essay, McHale speaks of difficult poetry deploying a kind of nonsense (e.g. versus “common sense”) that “ should be valued for itself, not as “a critique and demystification of current language practices” as he claims language-poets advocate (McHale: 1992, 25). Bernstein would rather speak of the “ideological” importance of those practices, the degree to which nonsense makes sense by unsettling expectations, and undermining seriousness. What I have called the cripistemological is when an ableist truism—your speech defect must be fixed—is cripped by exploiting the means of vocal production differently–in other words, to use error as another kind of sense. “Poetry, the kind of poetry I want, is not the unmediated expression of truth or virtue but the bent refractions, echoes, that express the material and historical particulars of lived experience” (43).

What I’ve called the ethics of the pataquerical appears when the counter-intuitive, counter-factual aspect of the poem creates, to paraphrase A.N. Whitehead, speaking of propositions, a “lure proposed for feeling” (Whitehead: 1960, 284). The end of the poem is the opening of (lure to) possible alternative avenues of meaning, sensation, knowledge. The book’s opening work, “Ocular Truth and the Irreparable Veil,” illustrates–quite literally–how a text “opens” possibilities by “closing” off its textual surface. “Ocular Truth” is a heavily redacted version of several prose essays, words and phrases blacked out to reveal a second hidden or alternate text. The poem’s title, based on Othello’s demand of Iago that he provide “ocular truth” of Desdemona’s infidelity is here complicated by a poem whose ocular truth is both revealed and obscured by blacked-out passages. One discerns a complex unweaving of several political themes concerning racism and cancel culture in a work that cancels portions of its prose. In the poem’s most readable (least censored) section, Bernstein responds to a New Yorker article by Peter Schjeldahl about the controversy over the cancellation of several exhibits of Philip Guston’s work.[6] The art critic sees these cancellations based on Guston’s representation of Ku Klux Klan images as “exemplifying divisions that are splintering the United States,” including attacks on cultural institutions, curricula, and public forums (Schjeldahl: 2020, 78). In his article Schjeldahl refers to those “cosmopolitan” audiences who complain of such cancellations and who espouse openness to troubling material against those who argue that an exhibit displaying racist subjects curated by an all-white staff is repugnant. Schjeldahl is of two minds, wanting to see the show but sympathetic to those “who neither find humor nor seek subtlety in racist symbology” (Schjeldahl: 2020, 78; Bernstein: 2024, 8). Bernstein seizes on the contradiction of an art critic who uses “cosmopolitan” to refer to an elite, culturally blinkered art audience when the term has historically been applied to Jews—like Philip Guston. It is as though one racial client has erased another, a fact embodied in a text censored like parts of Pound’s Pisan Cantos or Cold War FBI files. “Surely the problem,” Bernstein says in the poem, “is that Guston’s [word blacked out] figures are too legible—especially when coming from rootless cosmopolitans and cultural Bolshevists” (8). This is the conundrum that pervades the tone of aggrievement: that the cancellation of one form of art for revealing racism cancels an artist who is the historical subject of racism. Bernstein’s erasures, then, are perhaps the most “ocular” way to illustrate this conundrum. It is probably significant that Schjeldahl’s article was written on the cusp of the 2020 Trump election, an event that anticipated a more pervasive and troubling erasure of culture.

A Voice Pleading Aggrievement

The inaugural poem of this book sets the tone of aggrievement that permeates many of the essays and interviews. In one section Bernstein provides a mock blurb for an imagined anthology called “Alter Kockers”, using the Yiddish term used in Jewish comedy for an “old shit” and that includes “centuries of poems of bad advice and denial, guaranteed to pour salt on wounds large and small from poets who developed exquisite expertise in nursing ‘old wounds in old age…” (285). This may be Bernstein’s rueful comment on the resentment that comes with aging, now satirized in an anthology distributed by the “You Bet Your Life! Press’s Dorothy Parker collection.” It may also be a reference to the feeling of world-weariness in the current political battle over relevance. The Right is aggrieved at Wokeness while the Left is aggrieved at the Right’s aggrievement. Aggrievement is different from Nietzsche’s use of ressentiment to describe the resentment of the slave class at their subservience, placing the blame for their oppression onto the dominant class. Trump-era aggrievement would seem to be transactional, a zero-sum game of accusations and retribution rather than a dialectic of masters and slaves. Today’s aggrievement is a vicious circle: “A nightmare is haunting America and Europe; its slogan could be: ‘I am aggrieved by your aggrievement’” (42). The danger as Bernstein points out is a depoliticization and a “reversion to instinctual loyalties” (42). Aggrievement takes several forms in the book, despair at the failure of the poetics with which Bernstein is identified to accomplish a revolution in aesthetic tastes and practices. He is also aggrieved at the ways that this poetics has been attacked for its whiteness, elitism, racism, cosmopolitanism, the latter term marking the return of the repressed antisemitism associated with rootlessness. And finally, aggrievement describes the historical moment of Trump’s ascendency, his attacks on knowledge, culture, science, immigrants, and people of color.

But a final association with the term is the hidden “grief” in aggrievement, and here Bernstein’s own grief over the tragic death of his daughter, Emma, haunts his concerns about a world in a perpetual agon. To hear “grief” in aggrievement, is to rescue feelings of loss out of social resentment and suffer the calamity of one’s aggrievement: “The enemy of my enmity is my calamity.” Or again, “When the child dies, the father dies. It’s a mortal wound. What disappears in death grows wild in imagination” (152). Aggrievement may be the ontological form of dialectics, the way bottomless melancholia may be harnessed for resistance and critique. The mortal wound of a family’s loss cannot be healed, but it produces a wild imagination in the breach.

Conclusion

Being aggrieved can lead to a vertiginous binarism: “hatred of the avant-garde is prerequisite for entry into any official verse culture worth its smelling salts. the avant-garde is a

good target because it is, indeed, populated by fascists, miscreants, and malcontents…” (157). But surely the former holder of the Gray Chair of Poetics at Buffalo, the Donald Regan Chair at Penn, Fellow of the Academy of Arts and Sciences, winner of the Bollingen Prize— protests too much. This contradiction between the scourge of OVC and its invited guest speaks to Bernstein’s pataquerical imagination, attacking binaries by occupying them. OVC may be a straw man for a condition that doesn’t exist, but that’s no reason not to witness its impact, suffer its disregard. The “essays and comedies” as his subtitle to The Kinds indicates are spirited responses to various occasions and provocations, a chance to talk back to interviewers and interlocutors who, in some cases, have a much too sedimented notion of what he’s up to. Like Groucho, he unsettles those assumptions by not sticking to the point, going off on tangents, quoting a few lyrics from a Rogers and Hart musical.

The Kinds of Poetry I Want, like much of Bernstein’s work, courts its own instability, Neither a book of criticism, poetry, vaudeville act, or some kind of hybrid genre it’s all of the above and a good deal more. The book’s willingness to be uncool, even silly, makes it vulnerable to attacks by both conservative critics and Marxist scourges, attacks he encourages. The provocative nature of Bernstein’s often unfashionable positions is an occasion for dialogue, contestation, response. But as I’ve said with regard to its treatment of aggrievement, there’s a cost to being rootless, and the book records the historic implications of this condition as well as his own relationship to that charged condition. Like his friend, David Antin whose talk pieces fall between the stools of poetry, philosophical discourse, and stand-up/ improv, Bernstein’s pataquerical imagination pursues a poetics of errancy, what he calls “Aversive thinking” (“Avoid frame lock, trouble consistency” (341). In this book’s mosaic of genres and literary styles he avoids frame lock almost successfully. Emily Dickinson in one of her letters to Higginson, says, “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.” (Dickinson: 1986, 208) In Bernstein’s case, if a word falls from the ceiling, he knows that’s poetry.

References

Altieri, Charles. 1984. Self and Sensibility in Contemporary American Poetry. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Bernstein, Charles. 2011. Attack of the Difficult Poems. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

—. 2024. The Kinds of Poetry I Want: Essays and Comedies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

—. 1999. My Way: Speeches and Poems. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

—. 2016. The Pitch of Poetry. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

—. 1992. A Poetics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cecire, Natalia. 2019. Experimental: American Literature and the Aesthetic of Knowledge. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Davidson, Michael. 2022. Distressing Language: Disability and the Poetics of Error. New York: New York University Press.

Dickinson, Emily. 1986. Selected Letters. Ed. Thomas H. Johnson. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Kant, Immanuel. 1952. The Critique of Judgement. Trans. James Creed Meredith. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McHale, Brian. 1992. “Making (non) sense of postmodernist poetry.” In Language, Text, and Context: Essays in Stylistics. London: Routledge): 6-35.

Olson, Charles. 1947. Call Me Ishmael: A Study of Melville. San Francisco: City Lights Books.

Plath, Sylvia. 1981. “Lady Lazarus.” In The Collected Poems of Sylvia Plath. New York: Harper and Row. 244-47.

Quayson, Ato. 2007. Aesthetic Nervousness: Disability and the Crisis of Representation. New York: Columbia University Press.

Schjeldahl, Peter. 2020. “Us Cosmopolitans.” New Yorker 96.32: 78-79.

Whitehead, Alfred North. 1960. Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology. New York: Harper and Row.

[1] Charles Bernstein. The Kinds of Poetry I Want: Essays and Comedies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2024. Page numbers for all subsequent references to this volume will appear in parens without the title.

[2] For a full account of Bernstein’s early life see his interview with Loss Pequeño Glazer, “An Autobiographical Interview,” in My Way, pp. 229-52.

[3] On the Mongrel Collective see Alec Wilkinson, “Something Borrowed.” New Yorker, Sept. 28, 2015. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/10/05/something-borrowed-wilkinson; Janet Malcolm, “Strangers in Paradise: How Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas Got to Heaven.” The New Yorker November 6, 2006; Dorothy Wang, Thinking Its Presence: Form, Race, and Subjectivity in Contemporary Asian American Poetry. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2014; Juliana Spahr and Stephanie Young, “The Program Era and the Mainly White Room.” Los Angeles Review of Books, Sept. 20, 2015 https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/the-program-era-and-the-mainly-white-room/.

[4] See Bernstein’s “The Artifice of Absorption,” in A Poetics, pp. 9-89.

[5] See Distressing Language: Disability and the Poetics of Error, pp. 78-81.

[6] Peter Schjeldahl, “Us Cosmopolitans.” New Yorker 96.32 (19 Oct., 2020): 78-79.