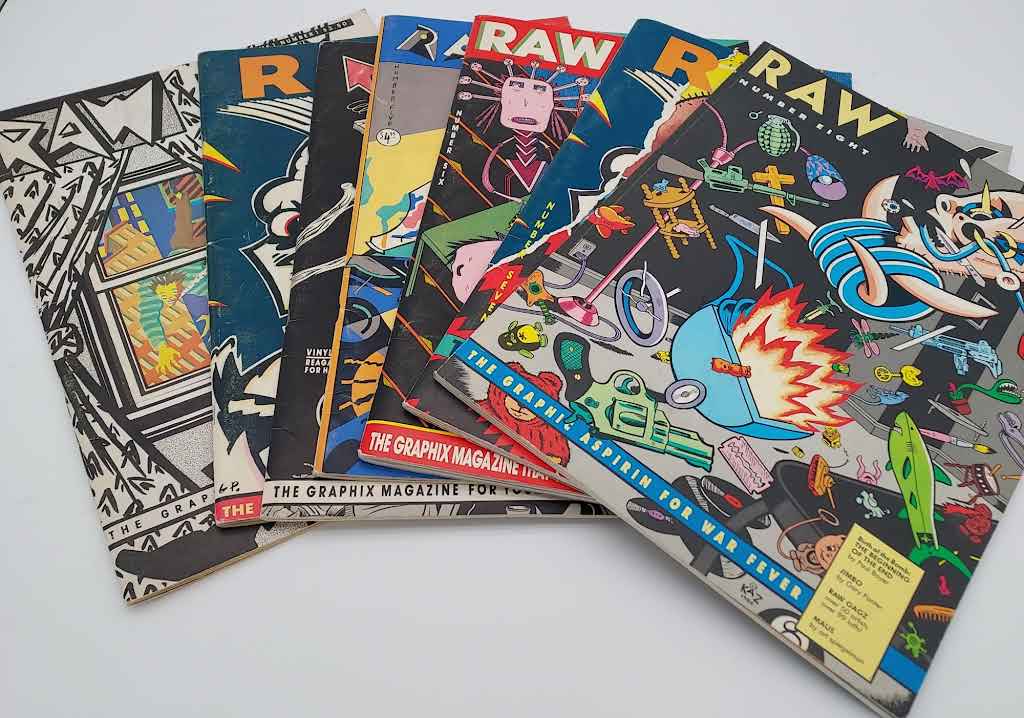

Fig. 1: Issues of the comics anthology magazine Raw, edited by Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly.

This article is part of the b2o: an online journal special issue “The Question of Literary Value”, edited by Alexander Dunst and Pieter Vermeulen.

To Understand Literary Value Today, Look to Visual Culture. Or, What the School of Visual Arts Tells Us About the Emergence of the Graphic Novel

Alexander Dunst

One of the more consequential developments in the study of literary value over the last two decades has been a renewed appreciation of literature’s institutional embeddedness. From James English’s study of the prize system (2005) and Mark McGurl’s focus on creative writing programs (2009) to more recent considerations of book reviewing (Chong 2020) and corporate publishing (Sinykin 2023), this attention has brought about a more fine-grained understanding of how different constituents collectively construct literature as worth their while. A similar interest characterizes a number of the contributions to the present cluster of essays, including Natalya Bekhta’s critique of the overemphasis on the (Anglophone) novel in literary studies, Günter Leypoldt’s argument for an ethnography of value, Maria Mäkelä’s consideration of literature in an age of social media, and Pieter Vermeulen’s interest in social acts of valuation.

While the research I have just mentioned elaborates on the changing processes of valuing literature, my own interest in these issues lies in how the nonliterary becomes valued, somewhat contradictorily, as literature. Practices of creative writing to use a purposively broad term, may be formalized in university education, or become enmeshed with digital platform affordances and the values espoused by prize committees that distinguish between the merely middlebrow and the award-worthy. In contrast, this short essay will trace how a particular medium sought to establish itself as literature, and what that history can tell us about literary value. As a consequence, I will be looking at the border regions of the literary field or, to use a phrase coined in a different context, at the “contact zones” of literature and the larger media ecology of which it forms a part (Pratt 1991, 33–40). My case study will demonstrate that literature continues to function as a term of value or distinction for media formats aiming to increase their prestige and attract new audiences within the larger cultural field.

Despite efforts to understand literature as part of a larger media system, most scholarship in literary studies remains reluctant to adopt this more wide-ranging perspective.[1] The reluctance, itself a largely institutional dynamic, is all the more surprising, and even detrimental to literary studies, as literary reading increasingly becomes one of many ways of engaging with culture rather than holding a privileged place within it. Bekhta’s argument that the equivocation of the novel with literature per se leads to blind spots in understanding its object of study may therefore be extended to the format that I focus on, namely the graphic novel (Bekhta).

Two curious, if minor, cases of oversight provide a gateway into the present inquiry. McGurl’s The Program Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing is one of the many examples of literary scholarship that speak broadly of contemporary fiction without engaging with graphic novels.[2] Only in a footnote does McGurl mention the “recent rise of the graphic novel to respectability” (2008, 447) and gives the examples of Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon’s Watchmen, the first two notable for being memoirs rather than works of fiction. However, McGurl does not connect the graphic novel to the topic of his own book, namely the historical significance of the rise of creative writing degrees for US literature. Extending this analysis, the edited volume After the Program Era explicitly seeks to remedy such lacunae, arguing on its very first page that:

[N]onfiction, drama, screenwriting, graphic novels, and electronic literature have increasingly become part of the creative writing curriculum, and work still needs to be done to understand the ways in which the form and content of these genres and modes have been influenced by this development. (Glass 2016, 1)

Somewhat surprisingly given this programmatic statement, the first mention of the graphic novel in the volume remains the only one throughout. How, then, have the “form and content” of the graphic novel—widely, if problematically, used as an umbrella term that subsumes nonfictional writing such as graphic memoirs and graphic journalism—been shaped by the inclusion into creative writing curricula?

A more complete study of that history remains to be written.[3] In its absence, I offer a brief sketch of how The School of Visual Arts (SVA) in Lower Manhattan, maybe the most prominent program teaching comics as an artistic practice in the United States, played its part in the transformation of comics into literature. For my account, I mainly draw on so-called “registration booklets”, which are kept in the SVA’s archive and during my visit there, in January 2020, were available for the years 1972 to 2015. These booklets, which elsewhere might be called module handbooks, list and describe courses, provide the names of teachers, and declare the aims and values of what is taught. Insofar as a course description cannot capture how students responded to their teachers’ aims and outlines, these documents are limited in scope. However, they provide insight into an element of comics and, indeed, literary culture that has rarely been considered.

The tradition of creative writing programs that McGurl traces only forms one contributing strand to this history. Comics writing and drawing is taught at different kinds of institutions, including research universities, liberal arts colleges, and most frequently at art schools. The degree denominations are similarly varied, ranging from hyphenated phrases like “Creative Writing: Graphic Novels and Comics” or “Creative Writing: Comics and Graphic Narratives” to more straightforwardly named MFAs in comics, in visual narrative, or in sequential art. Higher education as a place for training visual artists rather than literary authors then forms the other strand relevant to this account. In Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University, Howard Singerman traces the shift from nineteenth-century ateliers and academies to the emergence in the 1920s of the first master programs in fine art, better known under the abbreviation MFA, and their spread with the G.I. Bill after the Second World War. While the denomination has remained, this period saw a move towards reconceptualizing the fine as visual arts, influenced by the arrival of members of the Bauhaus from Germany (Singerman 1999, 69–70). It is no coincidence that the first institution training comics artists, founded as the Cartoonists and Illustrators School, renamed itself to reflect this development in 1955/56. Coming during a period of sustained growth for higher education, the name change reflected the ambition to understand cartoonists as visual artists.

Nonetheless, the education at the SVA remained focused on newspaper and magazine comics until the early 1970s (Gabilliet 2010, 503). Judging from the registration booklets, three teaching personalities dominated the program during the 1970s and early 1980s: Harvey Kurtzman, the founder of Mad, the serial comic books and magazine that ran from 1952 to 1956; Will Eisner, author of The Spirit comic series whose A Contract with God became an early, although not the first, example of the graphic novel; and finally Art Spiegelman, the co-editor of the magazines Arcade and Raw that brought an avant-garde aesthetic to American comics, who would go on to win a special Pulitzer for Maus.

The course descriptions of these years emphasize the artistic and, to a lesser extent, the literary ambition of comics. Kurtzman’s course, offered for several years, was titled “Political-Social Comics Art”, while Eisner taught a workshop in “Comic and Continuity Art” that aimed at creating both the more traditional comic strips and comic books (SVA, “Registration Booklet 1974–75”, 43 and 46). Other courses spoke of “visual literature” in their descriptions and emphasized adaptation from word to image, including poetry and the nineteenth-century novel (SVA, “Registration Booklet 1972–73, 65). When Spiegelman joined in the academic year 1977–78, he initially taught a historical overview titled “The Language of Comics”. Beginning in 1981, the cartooning major at the SVA started to advertise a new “Experimental Comics Workshop” taught by Spiegelman, which described itself as “devoted to testing the expressive possibilities of comics outside a commercial art context” and as grappling “with the problem of creating other new outlets for their [the students’] work” (SVA, “Registration Booklet 1981–82, 101).

The now traditional way of theorizing how teachers at the SVA conceived of comics at the time would be to speak, with Pierre Bourdieu, of an intensified phase of experimentation in the pursuit of a “pure aesthetic” (1993, 265). Bourdieu’s comment on experimentation remains pertinent. It’s less clear, of course, what “pure aesthetic” means in the context of comics, or whether that term captures something useful in the description of artistic change. If we want to move closer to how such experimentation might unfold, the dynamics of categorization and legitimation summarized by Michèle Lamont provide a more detailed model for how actors assign and contest value within institutions. Lamont mentions several categorization dynamics, including classification, equivalence, signaling, and standardization (2012, 204–205). Of these four, the first three are all present simultaneously, yet clearly in a state of flux. The course titles and descriptions classify comics as art and literature, sometimes directly with the help of compound phrases like “comics art” or “visual literature”. At other times, the language of adaptation from literary sources signals what might be called an aspirational equivalence with that source material: consider, for example, Spiegelman’s emphasis on “expressive possibilities” that more purposefully understands comics as a non-commercial, even potentially avant-garde, form.

What’s notable is the relative dominance of equating comics with art during this era and the absence of the moniker “graphic novel”, a term that appeared as early as 1964 in a fan publication and that authors and publishers increasingly used to refer to comic books during the 1970s (García 2015, 20). Two initial conclusions can be drawn from this, subject to correction based on a wider archival survey in the future. First, that the eventual adoption of the term “graphic novel” for book-length comics was by no means inevitable; nor was the book as a dominant format for the circulation and audience reception of contemporary comics. The repeated classification of comics as, and the equivalence sought with, art signals an alternative route that emphasizes drawing or other artistic techniques (watercolor, collage, linocut, etc.) over writing, image over text, and art exhibition over book publication. None of these elements are absent from contemporary graphic novels, but they tend to be overshadowed due to the eventual adoption of a term that established different priorities. Secondly, the relative preference for art rather than literature during this period of conceptual flux makes perfect sense for teaching comics at an art school like the SVA. But it begs at least two additional questions. Did a similar vocabulary of experimentation, proposing both art and literature as aspirational equivalences, exist in other institutions teaching comics?[4] And, most pertinently for the question of literary value: what led to the eventual adoption—or, in Lamont’s term, the “standardization”—of comic books as graphic novels?

After the breakthrough book publication of volume I of Maus in 1986, Spiegelman left the SVA while Eisner and Kurtzman continued teaching much as before. It took until 1992 for the term “graphic novel” to appear in the SVA’s registration booklets. Under the title “Graphic Novel for Cartoonists”, the course description promised “a unique blend of the excitement and flamboyance of the adventure comic book and the drama, authenticity and sophistication of serious illustration” (SVA, “Registration Booklet 1992–93, 158). Although the booklet repeatedly named the instructor as a “K. Jansen”, the emphasis on visual art makes it more likely that Klaus Janson taught the course. Together with Frank Miller, Janson had illustrated Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, a book that signaled the transformation of superhero fiction into graphic novels upon publication in 1986, the same year that Maus was released. Immediately below Janson’s, another course description emphasized writing skills for comics, including story, characterization, and plot, marking renewed attention to basic aspects of literature.

Over the next few years, uses of the designation “graphic novel” slowly expanded. In the 1994–95 booklet, a course titled “Science Fiction Art for the Graphic Novel Illustrator & Cartoonist” continued the somewhat awkward conjunction of literary and artistic terms, as if explaining the graphic novel’s relevance to art students. Similarly, a course on “Illustrating Words and Images” defined its aims as “an exercise to integrate literary and visual forms of communication” (SVA, “Registration Booklet 1994–95, 159-160). References to comic art or visual art did not disappear during these years but were increasingly accompanied by literary vocabulary. To return to Lamont’s sociological register, the course descriptions of the 1990s add elements of legitimation to the earlier categorization dynamics. The repetition of the term “graphic novel” can be seen as enacting its diffusion (Lamont 2012, 205).

At the same time, the course descriptions implicitly negotiate or contest the value of comics by arguing for the necessity of creative writing skills. The growing importance of such expertise for aspiring comics authors shows how creative writing pedagogy spread to other areas of artistic endeavor. At least in the case of the SVA, the adoption of novelistic storytelling in the medium of comics did not originate from within higher education but answered the example of established comics artists such as Spiegelman and the publishers keen on selling comics under the “graphic novel” label. Nonetheless, my case-study exemplifies how educational institutions have successfully promoted the value of literature even in areas where that might not be readily apparent.

In Lamont’s account, practices of valuing, diffusion, and negotiation work towards stabilization and standardization. Outside of the art school context, standardization arrived with the introduction of the shelf category “comics and graphic novels” in 2003 (Chute 2008, 462). Within the SVA, a stable conception of comics as graphic novels may similarly be traced to the 2000s. Starting with the 2002–03 academic year, a course in the “History of Storytelling” described a sequence from early comic strips and comic books to “the growth of graphic novels, and current developments in electronic media” (SVA, “Registration Booklet 2002–03, 162). The following year, an advanced storytelling workshop led by David Mazzuchelli emphasized “the voice of the author/artist”, a turn of phrase that privileges narrative elements. Perhaps most succinctly, “Storytelling I: Foundations of Comics Narrative”, taught by Jessica Abel, defined the graphic novel “as a personal mode of expression that achieves a meaningful balance between tradition and experimentation” (SVA, “Registration Booklet 2008–09, 210).

These descriptions accomplish the integration of visual and textual aspects very much on literary terms. Artistic skill continues to form the foundation of the graphic novelist’s craft but becomes subsumed under the demands of a narrative voice that prizes individual authenticity. In the process, Spiegelman’s experimentation outside of commercial contexts gives way to a “meaningful balance” that enables the graphic novel’s integration into the literary marketplace (Dunst 2023, 9). At the same time, the historical evolution suggested by the course on the “History of Storytelling” indicates that stabilization always remains temporary, with varieties of digital comics providing further horizons of change.

Drawing on earlier work in cultural sociology, Lamont suggests that institutionalization depends on the rhetorical force and resonance of specific acts of valuation, as well as the ability to successfully resolve conflicts (2012, 205). Addressing these points individually, it could be said that the conjunction of “graphic” and “novel” ties comics to the dominant literary genre of the novel in what I have called an aspirational equivalence. Literature functions as a reference value by which comics seek a metaphorical proximity that emphasizes forms of storytelling that can reasonably be called novelistic. The institutional resonance of this equivalence stems from the fact that US-American comics emerged within newspaper publishing and were already moving towards book publication when the graphic novel arose as a designation, with countercultural head shops and specialized comics stores replacing news vendors in the second half of the twentieth century. The challenges of shifting towards literary publishers and mass-market book stores should not be underestimated. This shift in production and distribution took another two decades to achieve but was accomplished precisely around the equivalence proposed by the term “graphic novel”. The conflict resolution mentioned by Lamont would seem to lie in the conception of the graphic novel as “a personal mode of expression” (in Abel’s words). Thus, the graphic novel channels “the voice of the author/artist” in a way that retains the emphasis on individual subjectivity promoted by countercultural and alternative comics in the 1960s to 1980s, which first established cartoonists as artists. In fact, there is a growing body of evidence that graphic novels, and contemporary US comics at large, have in the past decades only become more visual, with text diminishing in importance as digital printing has supported ever more detailed images and a wide range of artistic styles (Cohn et al. 2017, 19–37; Dunst 2023, 104–46). Thus, authorship subsumes and sustains artistry, both creatively and—what may count for more—by creating a profitable outlet for comics artists and industry within literary publishing.

Where does that leave the issue of literary value? For all the theorizing in this cluster of essays around use and exchange value, around more narrowly literary and wider societal values, the relationship between literature and other media remains largely absent from the discussion. This seems somewhat puzzling at a time when literature is ever more closely tied other cultural forms, whether by way of movie, television, audio or indeed comics adaptations, the integration of photographs and other visual material into literary texts, or the largely audiovisual marketing of literature and literary authorship on social media platforms (see Mäkelä, this issue).

This media ecology consists of different institutions, individual and collective actors including readers, artists, editors, and many others, as well as material objects and intellectual traditions of unequal prestige. Clearly, it was this power imbalance that attracted cartoonists to equate their visual narratives with novels. During the period of emergence that I have analyzed, the arguments for the graphic novel at the SVA drew less on the intra-literary (formal sophistication) and societal values (diversity and ethical witnessing) identified by Pieter Vermeulen and others for contemporary literature (2023). These become increasingly central with the integration into mainstream publishing, but the main equivalence remains with the novel tout court, its narrative possibilities and promise of cultural elevation. In this sense, the emergence of the graphic novel may offer a measure of reassurance to those who fear that the value of literature has eroded to a point where literature becomes indistinguishable from other commodities.

Ultimately, the history of the graphic novel at the SVA showcases the need to pay closer attention to the complex processes of assigning worth that take place within culture, or to what Raymond Williams famously described as “the relationships between elements in a whole way of life” (1961, 63). If that continues to pose a formidable challenge, it remains the case that any account of literary value that focuses solely on its socio-economic aspects or literature’s established genre system without taking account of larger media dynamics may end up with answers limited in scope and descriptive power.

References

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1993. “The Historical Genesis of a Pure Aesthetic”, in The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature, edited by Randall Johnson, 254–66. New York: Columbia University Press.

Boxall, Peter. 2013. Twenty-First Century Fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chong, Philippa K. 2020. Inside the Critics’ Circle: Book Reviewing in Uncertain Times. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Chute, Hillary. 2008. “Comics as Literature? Reading Graphic Narrative”, PMLA 123, no. 2: 452–65.

Dunst, Alexander. 2023. The Rise of the Graphic Novel: Computational Criticism and the Evolution of Literary Value. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

English, James F. 2005. The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Value. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gabilliet, Jean-Paul. 2010. Of Comics and Men: A Cultural History of American Comic Books. Transl. Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press.

García, Santiago. 2015. On the Graphic Novel. Transl. Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press.

Glass, Loren, editor. 2016. After the Program Era: The Past, Present, and Future of Creative Writing in the University. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Lamont, Michèle. 2012. “Toward a Comparative Sociology of Valuation and Evaluation”, Annual Review of Sociology 38, no. 1: 201–21.

McGurl, Mark. 2009. The Program Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Murray, Simone. 2025. The Digital Future of English: Literary Media Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pratt, Mary Louise. 1991. “Arts of the Contact Zone”, Profession: 33–40.

Singerman, Howard. 1999. Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Sinykin, Dan. 2023. Big Fiction: How Conglomeration Changed the Publishing Industry and American Literature. New York: Columbia University Press.

Vermeulen, Pieter. 2023. “The Indie Nobel? Stockholm, New York, and Twenty-First-Century Literary Value”, Journal of World Literature 8: 484–499.

Williams, Raymond. 1961. The Long Revolution. London: Chatto & Windus.

[1] See Simone Murray’s recent call for such an approach (Murray 2025).

[2] Boxall 2013 is another well-known example.

[3] The only critical engagement with teaching US-American comics that I am aware of can be found in Jean-Paul Gabilliet’s Of Comics and Men and concentrates on the early years of The School of Visual Arts (SVA) in New York City, the educational institution I will also focus on in what follows. However, his overview ends in the 1970s, the decade in which graphic novels really come into being (2010, 493 and 500–503).

[4] Most programs teaching comics as creative writing or artistic expression seem to be comparatively new but, once again, only a broader history would be able to establish an overview of past and current institutions.