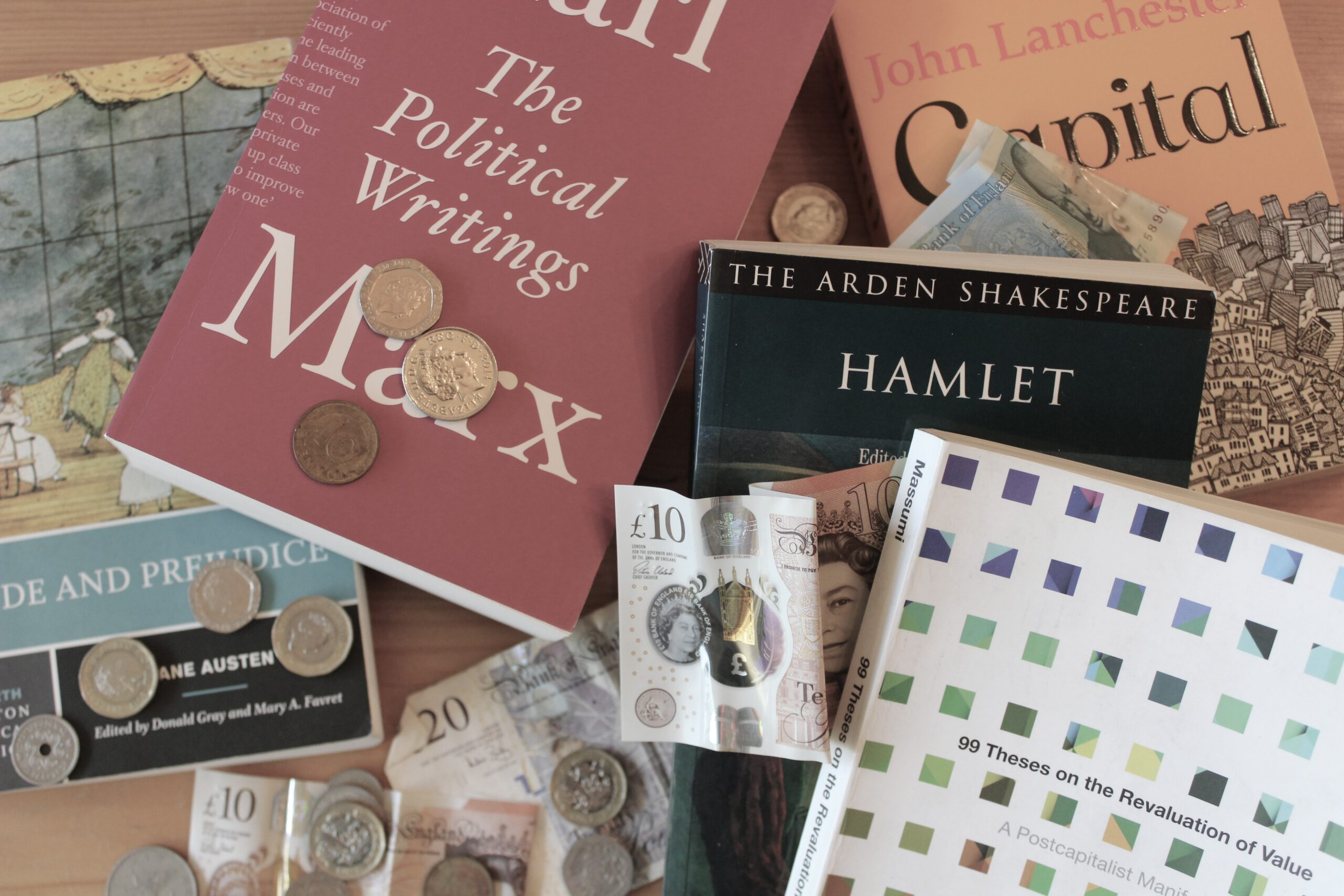

Photograph by the author.

This article is part of the b2o: an online journal special issue “The Question of Literary Value”, edited by Alexander Dunst and Pieter Vermeulen.

Literature and Literary Studies Can Contribute to a Revaluation of Economic Value, or, Imagining a Beyond to Capitalist Realism with Brian Massumi

Gerold Sedlmayr

In Thesis 8 of Theses on the Revaluation of Value: A Postcapitalist Manifesto (2018), Brian Massumi states: “The dominant notion of value in our epoch is economic” (2018, 5). While he therefore focuses on probing sustainable ways in which to rethink exactly this kind of value, the adjective “dominant” implies that other notions obviously exist but have been pushed into the background. These include, I assume, ethical and moral values. In the Oxford English Dictionary, such “values in the plural” (Nünning 2020, 330) are defined as “The principles or moral standards held by a person or social group; the generally accepted or personally held judgement of what is valuable and important in life” (Oxford English Dictionary 2025, def. II.6.d). Another notion that has been marginalized by the wide reach of the economic—the one that interests me here—is that of literary value.

Massumi’s manifesto rests on the idea that, in the twenty-first century, capitalism has subsumed all areas of life. As a postcapitalist, however, Massumi is not willing to follow theorists such as Mark Fisher, who, in his influential Capitalist Realism, claimed that an alternative to a society structured by a capitalist market logic is not thinkable anymore. With the notion of “capitalist realism” Fisher famously sought to capture “the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it” (2009, 2). Massumi, by contrast, claims that an alternative can be imagined. Not prepared to subscribe to the fatalistic “TINA” doctrine (“There Is No Alternative”), he demands

to take back value. For many, value has long been dismissed as a concept so thoroughly compromised, so soaked in normative strictures and stained by complicity with capitalist power, as to be unredeemable. This has only abandoned value to purveyors of normativity and apologists of economic oppression. Value is too valuable to be left in those hands (2018, 3; Thesis 1).

Although Massumi, as mentioned above, does not talk about literary value explicitly, it is conspicuous that many of the concepts which are crucial for his project of developing “a strong alternative conception of value” (3; Thesis 2) are concepts that are equally central to literary studies. Some of the most important of these are creativity, narrative, fabulation, affect, and beauty. In what follows, I suggest that interventions such as Massumi’s can give some productive impetus to discussions of literary and aesthetic value—and also, more generally, cultural value—particularly because they draw our attention to the interrelationship between these types of value and notions of economic value. After all, notions of aesthetic and literary value only emerged as specific objects of investigation once Western societies developed into industrialized market societies. In the second half of the eighteenth century, literary value and exchange value emerged in conjunction with and in distinction from each other. In the words of John Guillory: “A concept of specifically aesthetic value can be formulated only in the wake of the political economy’s discourse of exchange value” (1993, 316). Mary Poovey has shown that, still “at the end of the seventeenth century, one of the functions performed by imaginative writing in general”, of which she considers “Literary writing” to be a subset, “was to mediate value—that is, to help people understand the new credit economy and the market model of value that it promoted” (2008, 1-2). This mediating function, however, was given up at the turn of the nineteenth century: “it was not until Literature was declared to be a different kind of imaginative writing that a secular model of value completely at odds with the market model was articulated. When this occurred, Literary writing gave up its claim to be valuable in the old sense, precisely by insisting that it was more valuable in another, more novel sense” (2). Obviously, this view is still valid, at least among scholars of literature and culture: would not the great majority of us readily agree that we decided to study literature and not, say, economics, because we believed this pursuit to be of a ‘higher’, ‘truer’, and more ‘universal’ kind than the ‘shallow’ one of the ‘worshippers of mammon’? And is it not also the case that the issue of literary value has become so fashionable again in the last decade or so because we feel that the status of literature as cultural capital has begun to massively erode in the age of new media?

What genealogical enquiries such as Poovey’s into the historical becoming of the meaning(s) of value reveal is that literary value, precisely because its discursive emergence was so closely tied to the emergence of exchange value, cannot be properly re-considered without bearing the estranged kinship between literary and economic value in mind. This is all the more important because the respective attempts at demarcating a particular disciplinary field—whether it is ‘literature’ in literary studies or ‘the economy’ in economics—and hence at defining value in a manner specific to that field for a long time tended to gloss over the fact that lines of connection between those fields have never been wholly severed. On the one hand, ever since the early-modern patronage system ceased to exist, most literary writers have been dependent on the economic success of their works. Seen from this perspective, all attempts at distancing literary value from an economic ratio tend to become suspicious maneuvers: literary works, after all, are commodity products. On the other hand, in the words of Melissa Kennedy, “economics is a narrative of human interaction, invented and imagined into being with the help of figurative language and dominant story tropes” (2020, 158). Representations of ‘the economy’ make use of linguistic strategies that are also employed in literary texts, which is the reason why “literary studies’ interpretative and critical approaches open new ways of framing and engaging with economic criticism” (158). Economics is not as objective and, in the ethical sense, ‘value-free’ as it would like to be (see Sedláček 2011, 7).

This brings me back to Massumi. If we want to envision going beyond capitalist realism, Massumi writes, value will have to be “uncouple[d] … from quantification. Value must be recognized for what it is: irreducibly qualitative” (2018, 4; Thesis 5). Precisely because “[m]arket-based thinking”—by which he means, I assume, the kind of thinking represented by orthodox economics—is based on “the quantitative notion of value” (5; Thesis 8), the predatory tendencies of the prevailing economic logic can be disrupted and overturned by mobilizing the qualitative aspects that likewise determine the market. One example Massumi mentions early on is the real-estate sector, whose volatility cannot be wholly explained by way of endogenous factors—that is, factors internal to the market. If a neighborhood is expensive, this is also because it holds promises for the potential buyer that cannot be measured through mere quantitative means, namely a specific “quality of life” (8; Thesis 10) which in turn represents a specific form of symbolic capital. Therefore, “fluctuations internal to the operations of the market fundamentally hinge on a certain privileged non-economic factor: affect. Markets run on fear and hope, confidence and insecurity. … Affect cannot be considered to be squarely outside the market, but neither is it a formal market mechanism that is recognized as inside its system” (8; Thesis 11). Since for Massumi the term ‘affect’ refers to those qualitative factors which are both within and outside the market, they constitute what he calls its “immanent outside” (9; Thesis 11). To put his sophisticated argument in a nutshell: for him, it is precisely affects’ vital “excess-over”, their “overspilling” of quantitatively measurable market dynamics (9; Thesis 11) that we need to tap in order to return to a qualitative notion of value.

For Massumi, it is significant that the late-capitalist economy has itself created the conditions for its subversion through its ever-increasing financialization. Its prevalent tools, particularly financial derivatives such as futures contracts, predominantly operate in a virtual space in which a future outcome is imagined yet can never be securely predicted. According to Arjun Appadurai, “the derivative’s claim to value is essentially linguistic. Furthermore, its force is primarily performative, and is tied up with context, convention, and felicity” (2016, 4). In this way, financialization itself exceeds the limits of economic rationalism and protrudes into a virtual space whose aesthetic potential Massumi intends to mine, precisely because this space is only barely controllable by the financial sector. To put it differently, the speculative free-play of derivatives, Massumi believes, might provide a model for alternative instruments capable of turning over capitalist turn-over: “The turning of the turnover of capitalist surplus-value requires the alter-valuing of [capitalism’s] self-driving process. … A word for the alter-value that could drive a postcapitalist process is creativity” (19). This is exactly where aesthetics comes in. Quantitatively determined economic ways of thinking, Massumi suggests, might be deprived of their hegemonic status by putting a new stress on alternative and primarily qualitative forms of exchange. In order to identify such forms, he falls back on explicitly aesthetic categories: “Zest, beauty, wonder, and adventure provide aesthetic categories that might pave the way for the revaluation of values to go beyond normative criteria and judgment” (95; Thesis 77).

In a long section of his book that he tellingly captions “Fabulation” (2018, 111; Thesis 94), Massumi offers fourteen “[s]peculative strateg[ies]” (112–24). I would need a lot more space than I have here to explain them in any detail. However, even if I had, I would certainly question some of them, not least because I do not agree with everything Massumi characterizes as these strategies’ “anarchistic aspect” (119). More importantly, I would doubt their viability simply because I consider most of them as unrealistic, including those I support. This, however, is exactly the point. Their un-realistic, radical-utopian nature is meant to stimulate imagining an alternative to capitalist realism. Stimulating the imagination is precisely what they have in common with literary texts. At the same time, the fact that these strategies concretely aim at imagining a future makes for an uncanny analogy with futures contracts which, as their name indicates, allow speculators to envision a future profit. In Jens Beckert’s words: “The strongest similarity between literary texts and fictional expectations in the economy is that in both, actors proceed as if a described reality were true. … Expectations [of economic profit] are … fictional, based on imaginaries of the future or based on the ascription of transcending qualities, not on the foreknowledge of the future and the object as an empirical reality” (2016, 67). Yet whereas financial speculation is based on a quantitative notion of exchange value, Massumi’s speculative imagining is aimed at the release of a qualitative “surplus-value of life” (16; Thesis 16). In this sense, I read his approach as a radical-utopian suggestion to mobilize the potentialities of both literature and today’s hyper-financialized economy in order to eventually turn them against the latter.

My use of the phrase “radical utopianism” to characterize Massumi’s venture is taken from John Storey, according to whom “[r]adical utopianism confronts ‘realism’ with possibility. It gives us the resources to imagine the future in a different way. … [R]eality is the social ordering of the real into a hegemonic consensus. … When it is claimed that radical utopianism is unrealistic, it is against such constructions of reality it is contesting, rather than against some absolute reality” (2019, 1, 3). One of the concrete measures Massumi proposes to implement is the creation of a “digital affect-o-meter” with which to register “affective intensity” (121) in a “participation-based gift economy” (120). Whatever one might think about such a project, the point is not its immediate applicability but rather the development of a vocabulary for forms of speculation alternative to those that dominate the economy right now: “No account of value can do without criteria of evaluation. These terms [zest, beauty, wonder, adventure] provide elements of a vocabulary for the evaluation of the quality of the process coming to expression” (95; Thesis 77). As the section title indicates, this vocabulary is one of “Fabulation” (2018, 111; Thesis 94); it allows for imaginative, radical-utopian forms of speculation.

Taking my cue from Massumi, but in a much less grand and ambitious way, I suggest that we can put the insights of literary studies to valuable use in any project that investigates the narratives through which a specific economic system is legitimized in order to have a basis from which to develop alternative vocabularies. After all, is that not what literature ideally does and what therefore contributes to its value? In The Singularity of Literature, Derek Attridge describes literary “verbal creation” as “a handling of language whereby something we might call ‘otherness’, or ‘alterity,’ or ‘the other,’ is made, or allowed, to impact upon the existing configurations of an individual’s mental world—which is to say, upon a particular cultural field as it is embodied in a single subjectivity” (2004, 19) In addition, if the impact of the verbal creation is meant to be so strong as to disclose a genuine alternative, such an alternative can only be effectively envisioned once you have gained a proper knowledge of the reality, the “particular cultural field”, in relation to which it is supposed to introduce a difference. As John Clarke puts it: “Understanding the myths, stories, fantasies and fictions that work to sustain the apparent necessity of the dominant way of ‘doing’ the economy is a necessary critical moment” (2020, 30). Such understanding of economies as “imagined” (18), however, does not automatically mean (along the lines of Massumi’s anarchic manifesto) that every established way of ‘doing’ the economy has to be rejected as a whole. As I indicated above, I am actually skeptical about some of Massumi’s ideas, also because, in 2025, seven years after their publication, some of them may already require revision. For example, in times in which it has become abundantly clear how easily the digital space and AI technology can be manipulated and configured to roll back progressive thinking, Massumi’s trust in “[t]he possibilities for distributed agency offered by interactive digital platforms” (2018, 121; Thesis 94) has come to sound almost naïve.

Yet this is where another affordance of literature becomes relevant and so contributes to its value. The fact that it trains us in productive critical thinking by allowing us to read and interpret the world as a complex text also enables us to enter into negotiations over what is worth preserving. This might be, for example, the idea of the welfare state—an idea which was foundational for postwar democracies such as the UK or Germany but has been under severe attack for decades. Oddly enough, as voting behavior in recent years has illustrated, even many of those most likely to suffer from an erosion of the welfare state increasingly tend to support neoliberal agendas, obviously because the propagators of austerity policies are able to tell more effective stories—stories about, for instance, ‘benefit scroungers’, or about the inefficiency and sluggishness of state-run welfare institutions that allegedly do nothing but impede the pioneering spirit of entrepreneurs courageous enough to take a risk.

In 2009, at the height of the financial crisis, Fisher claimed that the naturalization of such narratives amounted to the abolishment of the ethical value system which had been the basis of the postwar consensus in Britain and elsewhere: “neoliberalism has sought to eliminate the very category of value in the ethical sense. Over the past thirty years [i.e., since the 1980s], capitalist realism has successfully installed a ‘business ontology’ in which it is simply obvious that everything in society, including healthcare and education, should be run as a business” (2009, 16–17). Although it is a commonplace among scholars of literature to claim that literary texts are exceptionally well-suited to mediate ethical values, it is perhaps less customary to likewise stress that literary texts also act as mediators of economic ideas.

Accordingly, it is worth pointing out that theories such as Massumi’s can only be effective if we, as scholars of literary and cultural studies, develop a genuine interest in understanding how the economy works. As Lawrence Grossberg puts it in “Considering Value: Rescuing Economies from the Economists”, a chapter of his book Cultural Studies in the Future Tense: “cultural studies”—as well as literary studies, I would add—“does need to take questions of economics more seriously, especially because of the specific realities, relations, and forces of the contemporary conjuncture. But … cultural studies [as well as literary studies] has to find another way of taking economies seriously, of incorporating economic questions into its analysis, which would not reproduce the reductionism of many forms of political economy” (2010, 105). In this sense, in the contemporary conjuncture dominated by populist political rhetoric, the zombie-esque revival of authoritarianism, and the rise of technocapitalism, a further important aspect that contributes to the value of literature can be found precisely in its anti-reductionism, in the ways in which it, through its status as a network interlinked with other networks (Meyer-Lee 2015, 341), keeps up a continuing exchange with the discourses that shape our lives, one of the most dominant of which is the economic discourse. The complexity of literature prevents the prefiguration of any one definitive value system, of course; literature is not positivistic in this sense. Rather, the production of literary value, not wholly dissimilar from that of exchange value, is dependent on a specific, historically contingent context and on the willingness of all parties involved to open up a space for genuine negotiation on equal terms. In a time in which digital media increasingly condition people to mostly read short and easily understandable texts in quick succession, the idea that literature, which requires patience and also the ability to tolerate ambiguity, can still function in this sense might be naïve. Whether it can still open up such a space is the litmus test it has so pass if it wants to remain relevant and be a purveyor of public value.

References

Appadurai, Arjun. 2016. Banking on Words: The Failure of Language in the Age of Derivative Finance. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Attridge, Derek. 2004. The Singularity of Literature. London and New York: Routledge.

Beckert, Jens. 2016. Imagined Futures: Fictional Expectations and Capitalist Dynamics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Clarke, John. 2020. “Why Imagined Economies?” In Imagined Economies / Real Fictions: New Perspectives on Economic Thinking in Great Britain, edited by Jessica Fischer and Gesa Stedman, 17–34. Bielefeld: transcript.

Fisher, Mark. 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Winchester: Zero Books.

Grossberg, Lawrence. 2010. Cultural Studies in the Future Tense. Durham: Duke University Press.

Kennedy, Melissa. 2020. “Imaginary Economies: Narratives for the 21st Century”. In Imagined Economies / Real Fictions: New Perspectives on Economic Thinking in Great Britain, edited by Jessica Fischer and Gesa Stedman, 157–74. Bielefeld: transcript.

Massumi, Brian. 2018. 99 Theses on the Revaluation of Value: A Postcapitalist Manifesto. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Meyer-Lee, Robert J. 2015. “Toward a Theory of Literary Valuing”. New Literary History 46, no. 2: 335–55.

Nünning, Vera. 2020. “Culture and Values”. In Key Concepts for the Study of Culture: An Introduction, edited by Vera Nünning, Philipp Löffler, and Margit Peterfy, 323–58. Trier: WVT.

Oxford English Dictionary, “value (n.),” September 2025, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/5277092424.

Poovey, Mary. 2008. Genres of the Credit Economy: Mediating Value in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Britain. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sedláček, Tomáš. 2011. Economy of Good and Evil: The Quest for Economic Meaning from Gilgamesh to Wall Street. New York: Oxford University Press.

Storey, John. 2019. Radical Utopianism and Cultural Studies: On Refusing to Be Realistic. London and New York: Routledge.