Jasper Bernes, The Work of Art in the Age of Deindustrialization (Stanford University Press, 2017)

Jasper Bernes, The Work of Art in the Age of Deindustrialization (Stanford University Press, 2017)

Reviewed by Laura Finch

Jasper Bernes’s The Work of Art in the Age of Deindustrialization inherits not only its title from Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility” (1936) but also Benjamin’s concern with the “developmental tendencies of art under present conditions of production” (Benjamin 2010 [1936]: 11). For Bernes this means tracing the dialectical relationship between poetry and labour over the course of the deindustrialisating era of post-1960s North America. One story that has been told of this relationship between art and late capital has been that of homology: the dematerialisation of both that can be seen in the correspondence between the related abstractions of the postmodern and the postindustrial. This argument has been made most famously by Fredric Jameson who depicts the post-1970s epoch of finance capital as the moment when “capital itself becomes free-floating [and] separates from the concrete context of its productive geography” (1997: 250-1), while analogously “the narrativized image fragments of a stereotypical postmodern language … suggest a new cultural realm or dimension that is independent of the former real world” (265). The converging narrative of aesthetics and labour that Bernes tells largely follows this logic of dematerialisation, where “the work of art and work in general share a common destiny” (Bernes 2017: 1, emphasis in original).

The story of deindustrialisation that Bernes narrates clearly and succinctly in his introduction describes the move from the profitable production-based economy of post-war industry towards financialisation, while automation led to a shift from a blue-collar to a white-collar workforce, a “massive demographic and occupational transformation, as workers moved away from goods-producing to service-providing sectors of the economy and as women entered the workplace in massive numbers” (179). Similarly, art turns away from making objects and in the wake of Duchamp increasingly treats its materials as things that need “rearranging, sorting, cataloguing, parsing, transcribing, excerpting” (21) such that “artwork becomes paperwork” (20).

However, where Jameson and Bernes diverge is in their analysis of the closeness of the relationship between art and capital. While for Jameson postmodern culture “cleaves almost too close to the skin of the economic to be stripped off and inspected in its own right,” (Jameson 1994: xv) [i], The Work of Art is interested in exactly the ways that culture and the economic inform one another. Bernes’s writing proceeds with a rigorous dialectical energy as he narrates the mutually influencing evolution of art and capital from the 1960s to the present day: that is, how does the shift in the North American economy in this period (from production and manufacturing to white-collar work) effect how labour is conceptualised, and how, in turn, does culture represent these changes? Rather than arguing that art and labour are exactly homologous or in direct opposition, The Work of Art details the convergence of art and work as a “complex set of reversible mediations” (1). Bernes works with what he terms a “loosely deterministic relationship,” where “the social and technical conditions of labor in a given society delimit a ‘horizon of possibilities’ for art” (33), an approach that “does not rely on simplistic notions of correspondence, homology or reflection” (33).

In Bernes’s account, the increasingly porous boundary between art work and work allowed the aesthetic to have agency in the transformation of the workplace. The corollary to the shift from factory production to office work also led to a change in the kind of demands workers were making on their employers: while during the first half of the twentieth century organized labour couched demands in a quantitative language, asking for better pay, shorter hours, greater job security, and safety protections, the latter half of the century brought a turn to explicitly qualitative demands such as “calls for greater participation in decision making, for a democratization of the workplace, for more varied and creative work, for greater autonomy, and even for [sic] self-management” (8).[ii] The relative difficulty of expressing a growing workplace ennui despite the quantitative gains made by the labour movement created a space for “various literary and artistic experimental cultures of the 1960s and 1970s … to articulate, though certainly not to create, these new qualitative complaints and demands” (8 italics in original), providing “tropes, motifs, and forms of articulation for [d]issatisfaction” (16) in the newly refigured workplace of deindustrialising North America.

The optimistic reading of the cultural response to the increased “alienation, monotony, and authoritarianism” (9) of the workplace is the commitment of artworks to critique the “division of labor between artist and spectator, writer and reader, which condemns the latter to inactivity” (15) by making of the art work “performances, conceptual elaborations, installations, environments, and earthworks” (11). However, this is not where Bernes’s account ends: under the pavement, the beach, but watch out for the dialectical kicker because “under the beach, the office” (130). While the turn to qualitative demands allowed for a shared vocabulary between art and work, this permeability came at a cost. While art helped to articulate problems of the workplace, these new articulations were then borrowed in turn by the workplace to further its own goals, such that “the critique of labor posed by experimental writers and artists of the postwar period became a significant force behind the restructuring of capitalism, by providing important coordinates, ideas, and images for that restructuring” (18). Here is the centre of Bernes’s argument, the case that he makes convincingly throughout the book: that, finally, “the qualitative critique of work passes into the quantitative worsening of work” ( Bernes acknowledges that he is not the first to make this claim, citing the work of Eve Chiapello and Luc Boltanski, Alan Liu, and David Harvey (17). However, he is interested in adding granularity to this claim by showing that while some aesthetic forms are co-opted wholesale (chapter one), at other times the art world and the corporate world are fighting it out over a set of terms made available by a third discourse (in chapter three, for example, the language of cybernetics).

Chapter one opens with of Frank O’Hara’s Lunch Poems (1964). O’Hara is a good choice – he is the poet of feelings and personal experience and this collection in particular, written by O’Hara in his lunchbreaks, is typically read in opposition to work: the stolen moments of artistic and bodily freedom as O’Hara walked through NYC on his breaks, “a lunch-hour flâneur in an urban landscape” (39). In contrast to this reading, Bernes reorients us to the ways that the Lunch Poems intersect with a vocabulary of work. In particular, O’Hara’s poems seem to foreshadow the turn from a focus on the commodity to the focus on aestheticised experience that was to become the central ploy of advertising, where “the commodity-object itself is simply a placeholder, an empty form that facilitates experience” (43). Retrospectively, O’Hara’s commitment to experience over the object (which puts him in line with a larger movement towards event and performance that Bernes traces throughout the art of the 1960s and 70s) seems to “prefigure and perhaps even contribut[e] to, indirectly” (41) the sale of experience by advertising. Bernes clearly shows this at work in the final lines of the poem “Having a Coke with You,” where O’Hara claims that the experiences of artists in the past were impoverished by their exclusive focus on objects: “it seems they were all cheated of some marvelous / experience / which is not going to go wasted on me which is why I’m telling / you about it.” Bernes’s sassy rejoinder to O’Hara’s call for pure experience is: “in other words: just do it,” (46) citing Nike’s ultimately motto as a bathetic reminder of the infinite recuperability of art by argument that 1960s counter-culture was swiftly recuperated by advertising is not new – in fact, Bernes gives a nice reading of how it is staged in the closing scene of Mad Men where Don Draper, with beatific smile, leverages his “proximity to liberated, bohemian spaces” (61) into Coca-Cola’s 1971 “Hilltop” commercial where the aesthetics of “perfect harmony” can be reached through “buy[ing] the world a Coke” (63). The likening of O’Hara to Nike and Mad Men works well, as do Bernes’s sharp close readings, for example when he makes the counter-intuitive claim that O’Hara is “a poet of service work as much as a poet of consumption” (39). Equally successful is the reading of O’Hara’s curatorial work at MoMA as a kind of training ground for his future shaping of New York as commodity, “cultivating an image of the worldly cultural space of New York for an equally worldly, international audience in the discursive context of the Cold War” (60).

Where I hesitate in Bernes’s reading of Lunch Poems is over the question of identity – a question that The Work of Art keeps bringing me back to. Let me pause on two readings of O’Hara mentioned by Bernes: Terrell Scott Herring’s “Frank O’Hara’s Open Closet,” and José Esteban Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia. Bernes turns to Herring’s theory of “impersonal intimacy” (2002: 422), a form of belonging that, Herring argues, O’Hara created as a queer counterpublic to provide (and create) sociality without the personalisation that would lead to the violence of surveillance. While Bernes recognises that O’Hara developed impersonal intimacy as a way “to solve the specific problems of queer counterpublics” (Bernes 2017: 50), his interest is in how this partial universalism made O’Hara’s work open to recuperation: for example, the creation of this affect through a circulating commodity (such as a can of Coke) was catnip to advertisers who sought exactly this kind of staged intimacy. Certainly, the tool of impersonal intimacy could, as Bernes writes, “anticipat[e] quite well the affective rhetorics that advertisers and retailers [would] use to lubricate the flow of commodities, generating rapport in the absence of familiarity” (50) (is “lubricate” being deployed by Bernes as a reminder of the queer history embedded here, or is it just a Freudian slip?). However, the too swift separation of the queer form from the content of O’Hara’s poems operates on the logic that O’Hara’s work and the history of labour are separable from O’Hara’s experience of sexuality.

We can see the consequence of this separation of queer from career in Herring and Bernes’s divergent readings of O’Hara’s “Poem”. Bernes reads the line “Lana Turner has collapsed!” as “available to us as mode and mood and model because it is not clearly addressed toward anyone or anything in particular” (53); Herring’s reading offers “Poem” as the “search [for] a localized public though it uses the techniques of mass subjectivity” (422). Further, Herring argues that “given O’Hara’s admiration for William Carlos Williams and for Williams’ belief that the poem should function as a material ‘thing’ in the social realm, it follows that individual men (or, potentially knowledgeable women) meet and attract each other through the circulation of the personal poem, a stimulant to desire akin to a tight pair of pants” (422).[iii] While for Bernes, O’Hara’s use of celebrity is an open invitation, Herring argues that Lana Turner’s position as gay icon attracts “a readership familiar with homosexual semiotic codes … the property of a mass public is now reclaimed for a particularized, more restricted audience” (422), and this audience is explicitly sexualised. Bernes’s claim to a mode, mood, and model of universalism is a move that effaces the erotic and the corporeal, both of which are necessary parts of Herring’s argument and of O’Hara’s life.

A similar move is made in relation to José Esteban Muñoz’s reading of O’Hara’s “Having a Coke with You” as “signif[ying] a vast lifeworld of queer relationality, an encrypted sociality, and a utopian potentiality” (6). Bernes terms this reading from Muñoz “exemplary” but swiftly closes down the queer potential by stating that Muñoz’s “dereifying maneuver … is itself rather easily reified” (44). Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia is exactly about the way that utopian queerness is so often silenced: “shutting down utopia is an easy move … social theory that invokes the concept of utopia has always been vulnerable to charges of naiveté, impracticality, or lack of rigor” (Muñoz 2009: 10).[iv] The thing is – Bernes is not anti-utopian. He is “not afraid to make claims for the effectivity of the aesthetic sphere” (6) and the book ends with the potential of a utopian horizon outside of work. Further, Muñoz’s reading is hardly against the history of labour: his O’Hara is a “queer cultural worke[r]” who can “detect an opening and indeterminacy in what for many people is a locked-down dead commodity” (9). I am not sure why Bernes is so quick to hand the coke bottle back to straight white masculinity, i.e. to Don Draper.[v] A queer reading is not antagonistic to a reading of the marketplace.

While Bernes is attendant to the specificities of O’Hara’s life insofar as they pertain to his work, spending a fair amount of time on O’Hara’s position as a curator at MoMA, the queer impetus that gives the poems their commercially recuperable form is quickly put to the side. This situates Bernes’s reading of O’Hara on a spectrum of criticism that separates identity politics and class criticism (whose bluntest proponent is Walter Benn Michaels and his frequently reiterated claims that identity politics are a distraction from the real work of class analysis[vi]). In the current moment, this feels like an impossible position to hold – although hasn’t it always felt impossible given the white supremacy that is the foundation and fuel for American capitalism? Bernes’s writing is not blunt; quite to the contrary, he is a generous and nuanced reader. However, this winnowing out of concerns that are outside of a very delimited idea of labour recurs throughout The Work of Art. I will return later to the epilogue of the book, titled “Overflow,” which uses the poetry of Fred Moten and Wendy Trevino to look at the relationship between race and labour. It suffices to say, for now, that the idea that a critique of wage labour could address sexuality or race only as an overflow is one that maintains the white, straight subject as the default and proper centre of labour history and separates vectors of social oppression from a class-based analysis.

Bernes is certainly aware of the problem of treating the straight white male worker as the only subject of history, and deals with this problematic universal in his second chapter. Rather than deny the central position of the white male worker to his narrative, Bernes argues instead that “such claims [to universality] derive from real features of white-collar work, since these workers were, in fact, often both bosses and employees, as well as mediators between executives and simple subordinates. This does not make their experience universal, but it does give such workers a uniquely privileged viewpoint, however full of contradictions” (66). It is through this idea of viewpoint that Bernes approaches John Ashbery’s writing. We begin with a setup: how on earth, asks Bernes, could we be expected to read Ashbery’s early work with the tools provided by poetry criticism when Ashbery’s use of proliferating points of view is more akin to that of a modernist novel? Citing a dozen lines from The Tennis Court Oath (Ashbery 1962), Bernes identifies five different viewpoints (as well as the multiple standpoints offered to the reader in the various pathways that can be taken through the poem’s exploded layout). In response to this proliferation of narrative standpoints and readerly viewpoints, Bernes suggests that free indirect discourse may be the best critical tool for navigation.

Turning to Marx’s work on commodities, Bernes reminds us that exchange occurs indirectly – we sell our time in order to make money, which we then use to buy the products of other peoples’ time. These transactions are also characterised by their appropriation by others, such that our work is not to create products for ourselves but to create products for an employer to sell. Bringing the analysis of poetic form and labour together we now see that “labor is both indirect (undertaken on behalf of others) and free (capable of being stripped from its producers and appropriated by someone else). We might say, therefore, that labor in capitalism is a form of free indirect activity, in which others act through us or we act on behalf of others” (78, italics in original). While free indirect activity is a consistent facet of capital, its formal centrality to Ashbery’s work is a sign of the newly slippery reversibility between layers of hierarchy within the corporation such that “management becomes more difficult to locate in a particular person, and the source of particular commands becomes more difficult to trace” (78). This confluence of Ashbery’s formal technique with economic theory is great: innovative and unexpected.

Bernes situates his reading of the universal voice of the white-collar worker in opposition to work such as Andrew Hoberek’s Twilight of the Middle Class: “whereas Hoberek wants to demystify white-collar pretensions to universality,” writes Bernes, “I argue that such claims derive from real features of white-collar work” (66). Again, it is unclear to me why these lines of argument have to be in opposition to each other. Both Hoberek’s and Bernes’s accounts of the formation of the white-collar worker are persuasive and accurate. Hoberek argues that the universal white white-collar subject was only made possible in its formation against a raced background of non-white blue-collar workers. Bernes’s reading of Ashbery serves to provide another dimension to the way that white privilege and capital work to prop each other up. A historical situation that presses white white-collar workers into a fractured and contradictory managerial position could certainly create a form of uniquely classed viewpoint; this managerialisation of the white-collar worker is also, as Hoberek writes, a “shift of focus from the manipulation of things to the manipulation of people[. T]he resulting, self-alienating collapse between person and thing is long established for African Americans … The white-collar class is formed in a crucible of the perceived [attack] both racially and economically” (2008: 68). Even if we set aside Hoberek’s desire to efface the universality of the white-collar worker, and accept that there was in fact a structurally new subject position open to the white managerial class, the formation of this white-collar position is created not just against blue-collar work but also against black bodies. That an argument about class feels the need to eject the specificity of certain bodies to make its argument speaks to the white elephant that isn’t in the room but is the room. As Glen Sean Coulthard (Yellowknives Dene) writes, capital is “a structure of domination predicated on dispossession … the sum effect of the diversity of interlocking oppressive social relations that constitute it” (2014: 15).

*

The next two chapters of The Work of Art burrow further into the mutual imbrication of work and leisure as we head further through the century. Chapter three details the brief but influential obsession with cybernetics in the 1950s and 60s, a distinctly masculine-gendered managerial approach that took on the same gender inflection in culture such that “if you were a white man and interested in experimentation in prose fiction in the 1960s and 1970s, then you were probably writing about machines, entropy, and information [i.e. cybernetics]” (85). In its promise of “social self-regulation based on horizontal, and participatory relations rather than explicit hierarchies” (29) cybernetics appealed as much to artists as it did to office managers who were looking to “trim administrative bloat” (29) and ease worker dissatisfaction. Chapter four continues this discussion of the dual exigencies of promoting worker morale and increasing profits by turning to the feminisation of labour where “not only [did] large numbers of women enter the workforce but labor methods and job positions [were] themselves feminized” (122). By importing ideas associated with leisure and home life into the workplace, the office was meant to be made more tolerable (29), while the further blurring of the line between life and work led to the now-familiar situation where “the entirety of life [is subsumed] by the protocols and routines of work” (30).

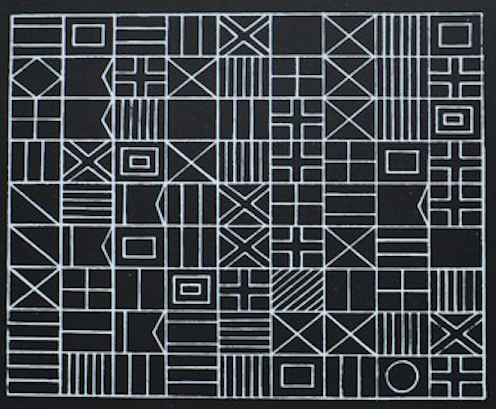

Bernes gives an impressively detailed history of the battle over cybernetics’ utopian possibilities. In line with the era’s general shift from control from above to self-management, cybernetics evolved from a Fordist/ Keynesian phase (a rigid and controlled structure) to the 1970s and beyond where “productive dynamism and creative disorder are valued over stability” (100). The post-1970s model led to management that was decentralised – workers do not get commands but are given “structures, protocols, and objectives” (104). This new freedom, is of course, not uncomplicated: “cybernetics presents an image of social self-regulation based on reciprocal, horizontal, and participatory relations rather than explicit hierarchies” (29). The open potential of cybernetics made it an interesting prospect across the political spectrum, both to employers hoping to cut costs by instituting self-governing practices of work and to artists who felt that cybernetics’ claims to totality offered the possibility of a utopian “global language” (101). This chapter is cautious in its assessment of the disruptive powers of the works it attends to. The ambivalence over what kind of freedom cybernetics would actually bring is at the centre of Hannah Weiner’s Code Poems (1968), which Bernes presents as a playing out of the conflicts over cybernetic potential: her poems are either “a model of the adaptivity, mutability, and openness to contingency that employers will demand from their workers” (106) or “a critique in advance of these new participatory models, revealing the violence and disorientation inherent in them” (106).[vii]

The false freedom of permutational choice was only one way that the tedium of the workplace was addressed: chapter four turns to the feminisation of labour as another corporate tactic to make work feel less tedious and automated. Through a reading of Bernadette Mayers’ Memory (a 1976 piece that mixes photography, performance, and text) Bernes criticises the way that the merging of private and public serves only to double the amount of labour the female worker has to do. Again, Bernes excels in his close attention to the texts – there’s a great reading of a scene in Memory where the staccato rhythm of a typewriter interacts with the rhythm of dishwashing to display the collapse of the once separate spheres of domestic life and office labour.

Bernes argues that this collapse is not only spatial – as the metaphor of spheres would suggest – but also creates “forms of interconnection that are temporal” (125): women must work the “double day … of paid and unpaid labor” (126). Time is also encountered through the growing role of technology in the 1970s. Here, Bernes takes another detour through Marx, describing a “temporality where the past remains present in an objective form, in the form of material accumulation that makes demands on, limits, and fates the course of the present. This is the sense in which Marx’s project is historical materialism – an account of history and historical change as materialized force” (140). This can be seen in Mayer’s Memory where “the superabundant complexity of her documented past comes to require continuous transfusions of present attention and creates … an explicit sense of tyrannical control in her presentation of the relationship between past and present” (142). The weight of this past is what Marx calls the “general intellect,” that is the huge amounts of knowledge stored in machinery that are external to man and therefore make the past an alienated and over-determined behemouth “speed[ing] onward, relentlessly, but not toward anything” (148). Beyond the faster pace of the growth of technology in the contemporary era, it strikes me that this description of Memory where “attempting to document the past in all its fullness, continually creates new, undocumented pasts” (144) could just as well apply to, for example, Samuel Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape (1958) as to the information age.

Perhaps a more surprising link not made (given the title of Bernes’s book) is to Walter Benjamin’s much theorised Angel of History, that celestial “historical materialist” who, like Mayer, “would like to pause for a moment so fair, to awaken the dead and to piece together what has been smashed” (Benjamin 2007 [1955]: 257) but cannot as the rubble piles up in front of him.[viii]

The motivation of both chapter three and four are a little less clear than the first two chapters. The readings of Weiner (chapter three) and Mayer (chapter four) interestingly flesh out histories of cybernetics and the accelerated work day. However, the conclusion that these chapters reach – that artworks have an ambivalence such that “what is potentially revolutionary in one moment can become definitively system reinforcing in another” (117) and that the past materialisation of capital makes “the present a mere adjunct to the past” (148) – are not specifically new to the deindustrialised age. Possibly this is an intentional move in order to show that there is continuity (with intensification) across the century as well as a break in the 1960s, but if so the argument is not brought out quite clearly enough for this reader to find it.

*

The final chapter of The Work of Art hops forward to the twenty-first century in order to look at the effect on art of this over-determination by the general intellect, i.e. “what happens when art confronts a workplace whose very technologies, attitudes, and structures are a materialization of its own defeated challenges?” (156)[ix] We turn first to Flarf poetry, an experimental form that emerged in 2001 that mines the internet’s propensity for ridiculous juxtapositions; as Flarf-er Mike Magee puts it: “you search Google for 2 disparate terms, like ‘anarchy + tuna melt’” and stitch the quotes captured by Google into a poem (qtd. on 157). Flarf is explicitly tied to the workplace, both by “fucking around on the man’s dime” (164) as another Flarf practitioner Drew Gardner claims, and also by re-purposing the language of technology. The anhedonic other of Flarf is conceptual poetry, which creates homologies with clerical work by framing itself, in the words of Kenneth Goldsmith, as “information management” (qtd. on 166). Bernes cites Vanessa Place’s Statement of Facts – a reproduction of the briefs she wrote as a public criminal Appellate defence lawyer – as “one of the most remarkable confirmations of the thesis that work activity and nonwork activity have become nearly identical at present” (167).[x] Faced with the qualitative demands of white collar workers, capitalism takes these demands and converts them into a banalised version (156): demands for community are replaced by team work; for variety by adding more responsibilities to job descriptions; to complaints of the domination of work over life, employers responded with contingent and flexible labour; and the demand for creativity was taken in and spat back as the playful workplace that might offer you a growing wall and granola while exploiting you for longer hours.

Articulating an exitlessness that is redolent of Adorno and Horkheimer’s view of the culture industry, Bernes asks: “what possibilities for the aesthetic critique of work remain now that workplaces have been designed to anticipate and neutralize such critiques?” (156). Seeing conceptual poetry’s “emptying out of the libidinal content of the work landscape” (168) as a return to the very workplace tedium that began the narrative of his book, Bernes suggests the work of British poet Sean Bonney as a possible escape from this bind. Writing from a place of long-term unemployment, Bonney locates his critique of labour from outside the productive sphere of the gainfully employed. Of course, unemployment is bound up with precarity and “given the tendency of release from work to become a lack of work, or unwork, such joys are inextricable from agonies various and sundry” (172). (In particular, the Jobseeker’s Act of 1996 shifted the terminology in the UK from “unemployment benefits” to “Jobseeker’s Allowance” such that not working is always also a form of work.) Despite the difficulty of positioning oneself outside the labour market, it allows Bernes to find a space of possibility: “perhaps the task of the aesthetic challenge of our time is not to demand freedom in work but freedom from work” (171). No one is going to disagree with that sentiment, although whether escape from work is the most useful utopian horizon of course depends on one’s subject position. This point is briefly addressed with the inclusion of the Mexican American poet Wendy Trevino, who swats away the idea that the desire to be freed from work is anything to do with poetic freedom: “I’ve been told grant writing / Will ruin my writing. In the long list / Of reasons I wish I could quit my job / What it’s doing to my poems is absent” (196). I would have liked to see more of a critique of the demographically-limited possibility of un-work than this brief moment spent with Trevino.

This brings us to the previously mentioned Epilogue, containing the “overflow” of the book. It opens with a history of the vagabond as a way of living outside of labour, where Bernes writes that “just as literary history provides numerous examples of a poetics of labor so too there is an abundance of formal and thematic resources from which we might elaborate a poetics of wagelessness” (184), citing examples that range from broadside ballads to Wordsworth, John Dos Passos to Claude McKay. Bernes then links the “fugitivity” of the vagabond to the theorisation of fugitivity in Fred Moten’s work (189). One model of this fugitivity, Bernes suggests, is Sean Bonney’s turn away from work. The application of Moten’s terminology to the white poet Bonney is justified, for Bernes, by Moten’s statement that the use of fugitivity can “expan[d], ultimately, in the direction of anyone who wants to claim it” (qtd. on 193). This leads Bernes to write that “the African American radical tradition, both poetic and political, provides examples that will be increasingly crucial for all antagonists to capital and the state” (193). On the one hand, this desire for an all-inclusive collaboration of anti-capitalist agitators is exactly what will be necessary when we crush the state. On the other hand, the attention to emancipatory African American aesthetics arrives only when they become relevant to the increasingly precarious position of white male workers. This clarifies what has been a cumulative experience over the course of reading The Work of Art, namely that even a book that is explicitly thinking about production still manages to theorise art outside of the full conditions of its production by circumscribing “work” to the limited sphere of class.

*

Instead of moving from particular to universal, I will conclude with a little specificity by spending some time with Wendy Trevino.[xi] The work that is addressed in Bernes’s Epilogue is her 2015 piece, “Sonnets of Brass Knuckles Doodles.” This sonnet is centered on Trevino’s job at a nonprofit organization and the fraught fact that she is there working for a white female poet whom she met through poetry circles. Bernes focuses on the way that Trevino documents “the vanishing of the boundary between work and life under the force of new, social media that instrumentalize the affective languages of friendship … [and] the incorporation of artistic technologies and relationships into the work place” (195). Bernes then, importantly I think, shows how Trevino resists this encroachment of work upon her life:

According to Human Resources, I’m white.

I have been confused for other women

With dark hair. Maybe I am them sometimes.

In the elevator, taking the stairs

Walking back from lunch, saying ‘it’s not me.’ (Trevino 2015)[xii]

Of this moment, Bernes writes that “work is all-encompassing but its compulsive identifications – its identity with the self – can be resisted. For Trevino, this means refusing the identifications of poetry as well” (195). This is true – Trevino wrestles with the structural difficulty of writing in the enmeshed sites of the workplace and the institutions of poetry. But these lines are also about race and ethnicity. Her refusal of work – “it’s not me” – is a refusal of all the things Bernes lists, but also a refusal of the inadequate racial categories offered by human resources and of the fungibility created between herself and other women based on ethnic markers.

In the penultimate verse of this ten-sonnet cycle, she also writes:

Next time we talk about race & poetry

I’d be interested in talking about

How many poets of color end up

Working for their white friends, who are also

Poets & how that might affect what they

Write & publish & do & how they talk

About it – instead of talking about

How many poets of color are in

This or that anthology. We always

Talk about that. More than half the staff of

The non-profit I work for are people

Of color. For various fundraising

Materials, they tell their stories. They

All sound the same & don’t take up much space.

Certainly, the collapse of work place and art work is evident in the parallel ways that these arenas both demand the inclusion of the voices of women of colour, while simultaneously disregarding them. But there is more. The stanza opens with the conjunction “race & poetry,” and while the workplace is discussed, it is under this interpretational rubric. Having posited this dyad as the centre of the stanza, Trevino directs the reader to the more and less important ways that race and poetry can be addressed. There is a clear “we” and “I” in this stanza. The “we” talks about the number of people of colour included in poetic journals, the alliterative “this and that” pointing to the banality of an abstract inclusivity when it is reduced to a statistic. The “I” points to a different form of sociality. It is plural, linked immediately with the other people of colour that Trevino works. From this plurality, the “I” is not interested in inclusion, when this inclusion means adding a single name to the contents page of a journal while leaving the material condition of the (indistinguishable, negligible) co-workers untouched. We can see here that without an analysis of race (and at other times in “Sonnets of Brass Knuckles Doodles,” gender) the material inequities of class cannot be approached.

Part of the difficulty of writing about certain topics is the whiteness of the archive. I find Sara Ahmed’s work good to think with here, in particular her idea of building a citational house that welcomes those beyond whiteness. To this end, Ahmed has a clear policy in her book Living a Feminist Life: “to not cite any white men. By white men I am referring to an institution … Instead I cite those who have contributed to the intellectual genealogy of feminism and antiracism” (15). This is a strong policy, which makes sense in the context of Ahmed’s book, which is a (brilliant) toolkit for thinking, feeling, living feminism. Not all books need, should, can, be as trenchant as this in their citational practices. However, as Ahmed writes, “citations can be feminist bricks: they are the materials through which, from which, we create our dwellings. My citation policy has affected the kind of house I have built” (16).

No matter how compelling the individual readings are in Bernes’s The Work of Art, as a whole it implicitly makes the claim that “gender and race are not material while class is material, an argument articulated so often that it feels like another wall, another blockage that stops us getting through” (Ahmed 147). The experience of reading a history of deindustralisation in the U.S. that sequesters gender to one chapter and race to an Epilogue confronts the reader with the inhospitality of a white house that serves only to remind her of the ways that her gender, race, sexuality, or ethnicity are barriers to entry. As Trevino shows us, we need to think about race when we write about white poets. We also need to think about gender when we write about male poets, sexuality when we write about straight poets, disability when we write about able-bodied poets. This, and only this, will destabilise the white male as the universal category where race, gender, sexuality, and disability can be sloughed off as the concerns of others – namely the bodies that bear those categories.

References

Ahmed, Sara. 2017, Living a Feminist Life. Durham: Duke University Press.

Benjamin, Walter. 2007 [1955]. “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility.” Trans. Harry Zohn. In Illuminations. Schocken Books: New York.

Bernes, Jasper. 2017. The Work of Art in the Age of Deindustrialization. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Coulthard, Glen Sean. 2014. Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Goldman, Judith. 2001. “Hannah=hannaH: Politics, Ethics, and Clairvoyance in the Work of Hannah Weiner.” differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 12.2: 121-168.

Herring, Terrell Scott. 2002. “Frank O’Hara’s Open Closet.” MLA 117. 3: 414-427.

Hoberek, Andrew. 2005. The Twilight of the Middle Class: Post-World War II American Fiction and White-Collar Work. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Jameson, Fredric. –. 1994. Postmodernism, Or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

–. 1997. “Culture and Finance Capital.” Critical Inquiry 24.1: 246-65.

McCarthy, Michael A. 2016. “Alternatives: Silent Compulsions: Capitalist Markets and Race.” Studies in Political Economy 97.2: 195-205.

Michaels, Walter Benn. 2016. The Trouble with Diversity: How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality. New York: Picador.

Muñoz, José Esteban. 2009. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: New York University Press.

O’Hara, Frank. 1995 [1959]. “Personism: A Manifesto.” In The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara. Ed. Donald Allen. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Roediger, David R. 2017. Class, Race and Marxism. London and New York: Verso.

Trevino, Wendy. 2015. “Sonnets of Brass Knuckles Doodles.” Boog City Reader. 8 (2015) http://www.boogcity.com/boogpdfs/bc95.pdf

Zultanski, Steven. 2012. “Short statement in five parts on Statement of Facts: A review of Vanessa Place’s Statement of Facts.” http://jacket2.org/reviews/short-statement-five-parts-statement-facts

Notes

[i] Jameson uses the terms synonymously at times: for example, “the economic preparation of postmodernism or late capitalism began in the 1950s” (Jameson 1994: xx).

[ii] Of course, quantitative demands such as shorter hours hopefully lead to a qualitative improvement of work conditions, but the distinction Bernes is making here is between the language that these demands are couched in.

[iii] The image of the “tight pair of pants” is a reference to O’Hara’s “Personism: A Manifesto,” where he celebrates poetry’s inextricable relationship with consumerism: “as for measure and other technical apparatus … if you’re going to buy a pair of pants you want them to be tight enough so everyone will want to go to bed with you” (O’Hara 1995 [1959]: 498-99).

[iv] Sara Ahmed provides an invaluable defense of the intellectual rigour of hope: “I am relatively comfortable in critical theory, but I do not deposit my hope there, nor do I think this is a particularly difficult place to be: if anything, I think it is easier to do more abstract and general theoretical work … The empirical work, the world that exists, is for me where the difficulties and thus the challenges reside. Critical theory is like any language; you can learn it, and when you learn it, you begin to move around in it. Of course, it can be difficult, when you do not have the orientation tools to navigate your way around a new landscape. But explaining phenomena like racism and sexism—how they are reproduced, how they keep being reproduced – is not something we can do simply by learning a new language. It is not a difficulty that can be resolved by familiarity or repetition; in fact, familiarity and repetition are the source of difficulty; they are what need to be explained” (Ahmed 2017: 9).

[v] In fact, not even Don Draper can keep a straight face: he only becomes Don Draper by closeting his birth name Richard “Dick” Whitman.

[vi] In particular, see The Trouble with Diversity: How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality (Benn Michaels 2016). For refutations of this argument see “Alternatives: Silent Compulsions: Capitalist Markets and Race” (McCarthy 2016) and Class, Race and Marxism (Roediger 2017).

[vii] While Bernes points out that cybernetics is a hyper-masculine domain, he does not make anything of the fact that Hannah Weiner is his key exemplar. For a reading of Weiner’s code in relation to gender, see Goldman, 2001. For Goldman, Weiner’s Code Poems reveal “gender [as] a code for code and additionally a code for the intrinsic failure of code to carry a stable meaning: gender as an error message” (2001: 128).

[viii] Thanks to Katy Hardy for pointing out this parallel with Benjamin, and more broadly thanks to Jessica Hurley, Isabel Gabel, and Thea Riofrancos for their comments.

[ix] A version of this chapter appeared as “Art, Work, Endlessness: Flarf and Conceptual Poetry among the Trolls” in Critical Inquiry in 2016. A version of chapter two appeared as “John Ashbery’s Free Indirect Labor” in MLQ, 2013.

[x] It feels strange to discuss Place and Goldsmith without referring to the controversies surrounding the anti-black sentiments of their more recent work (Place’s tweeting of Gone with the Wind in its entirety; Goldsmith’s reading of Michael Brown’s autopsy) or Marjorie Perloff’s response to Place’s Statement of Facts at the 2010 Rethinking Poetics conference, where she “caused the audience to collectively gasp when she claimed that what Statement of Facts reveals to us is that the victims of rape are ‘at least as bad as or worse than the rapists’” (Zultanski 2012).

[xi] Thanks to Arne de Boever for encouraging me to write this section. (Of course, all responsibility for its content rests on my head alone.)

[xii] The title is misspelled in The Work of Art as “Sonnets of Brass Knuckle Doodles.”