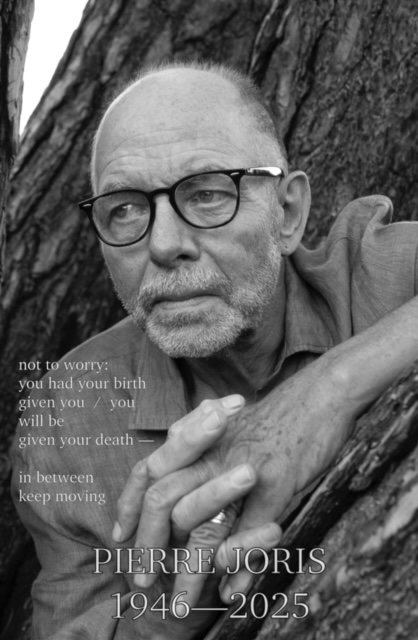

This article was published as part of the b2o review‘s “Finance and Fiction” dossier.

The Anxiety of Inflation (On Ben Lerner’s The Lights)

Peter Makhlouf

“Then he was aware of moving at an impossibly smooth rate, and there was the Brooklyn Bridge, cablework sparkling, Liza was cursing at the little touch-screen television in the taxi, which she couldn’t seem to turn off, and he reached out a hand to help her and experienced contact with the glass as a marvel, like encountering solidified, sensate air.”

—Ben Lerner, 10:04

Again the traffic lights that skim thy swift

Unfractioned idiom, immaculate sigh of stars,

Beading thy path—condense eternity[i]

Hart Crane’s inspired dedication to Brooklyn Bridge revisits ancient paradigms of influence. Originating as a late antique astrological concept, influence or influentia, as it was known, named the astral flux emitted from heavenly bodies. This starry stuff formed the material substrate for an otherwise immaterial soul. The common substance of star and soul underwrote the belief that stars exercise an outsized “influence” on our earthly fate, particularly our poetic faculty (or lack thereof). Crane’s invocation transmembers[ii] the astral idiom of the ancients: the influxus stellarum (“starry flux”) filling the soul of the poet becomes the artificial lights sweeping across the bridge’s steeled thews. Modern tectonic feats become a well of inspiration for modern American poetry.

According to this ancient doctrine, starry influentia shapes both our productive and reproductive capacities, both creation and procreation. The formative thrust of influence is thus bound to the projection of futures plastic and possible or fated and foregone. In newspaper columns, among the blogosphere exegetes of the zodiac, this ancient doctrine persists into our culture today—but transformed. Witness the determinist lore that populates modern astrological occultism, which so infuriated Theodor Adorno at mid-century.[iii] Adorno detected in Americans’ starry-eyed fascination with astrology a displacement of the fatal sense of helplessness incited by capitalism and its unfettered technological domination.

Inlayed in the ocean floor beneath the Brooklyn Bridge is one of North America’s densest concentrations of fiber optic cables.[iv] The proliferation of these vast undersea networks in the last half century has been driven by the exigencies of high-volume, high-frequency trading.[v] Beginning in the 1980s, telecommunications companies carried out Promethean feats of engineering in order to outfit Lower Manhattan with one of the globe’s most sophisticated infrastructures for lightspeed internet connection. The Brooklyn Bridge is just “[d]own Wall [St. -PM],” Crane reminds us in his invocation, and financial markets have served as the engine driving continued private investment in these local fiber optic networks. For competitive advantage often comes in the form of milliseconds won thanks to faster connections.[vi] “[M]odernization project[s] will make lower Manhattan ‘future-proof,’”[vii] Verizon proudly informs us. Such infrastructures will ensure that automated future trading can progress unabated even if New York City is swallowed up by the very environmental catastrophes that these energy-intensive systems exacerbate. The ancients figured starry influence as a luciform body (αὐγοειδές/φωτοειδής)[viii]; Crane romantically re-metaphorized physical lights as stars; the pulses of light that speed along fiber optic cables and transmit reams of data (whether a poem or a derivatives trade) literalize the metaphor once and for all.

Crane’s The Bridge and Whitman’s “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” are the two primary influences on Brooklyn resident Ben Lerner’s recent collection The Lights[ix], which, as the opening poem “INDEX OF THEMES” informs us, is composed of:

Poems

about stars and

how they are erased by street

lights (3) […].

We awake in a desolate wasteland of light pollution, a lambent storm of celestial rays, blue light, metaphors, materials, the “soft | glow of the screen [which] comes off on our hands” (4), as ink once might have. The poet is fretfully aware that technological development has eclipsed these once stalwart symbols of poetic influence:

At some point I realized the questions were the same questions. […] I’m tracking the advent of the credit economy. The implications for folk music of the fact that stars don’t twinkle—the apparent perturbation of stars is just a fluctuation in the medium—is something we want to understand. (18)

The stars have been erased first by street lights (still quaint) and, eventually, by the credit economy’s pulses of light, darting below the East River. Fluctuating media expose this primary trope of influence as an optical illusion. What Lerner here terms “folk music” names the object of his quest in these poems: a form of collective enunciation with which the lyric voice may or may not be commensurate. But why is the evanescence of starlight a matter for folk music? And why is this the same question as delving into the advent of the credit economy?

As I explore in what follows, the lights of Lerner’s title figure nothing less than the prodigious effectivity of today’s fusion of finance and media, which generates influence at a scale far surpassing that of literary writing. Rather than understand the anxiety of influence at play in Lerner’s work within the Bloomian drama of literary history—a gigantomachia of poet against poet[x]— the theory of poetry here proposed reconstrues the post-Romantic condition of belatedness as the fate of the poet in the age of digital technology, with its propensity to colonize futures through self-realizing financial models. Lerner’s poetry vies with the financial fictions of traded futures, which foreclose upon poetry’s ability to imagine alternative worlds. [xi]

On the example of The Lights, this essay seeks to reconceive “the exhaustions of being a latecomer” (to borrow a Bloomian locution) in light of the atrophy of imaginative power precipitated by market logics. Fernand Braudel famously christened the advent of financialization “a sign of autumn,” a late-stage in the palingenetic cycle of capitalist accumulation. For scholars of literature, such autumnal metaphorics are mainstays of the poetic tradition. In the feuilles mortes of Verlaine’s “Chanson d’Automne,” the “limp leaves” rounding out Eliot’s The Wasteland, fall surfaces time and again as a guiding trope for the burden of modern literature’s belatedness, the impotence of its influence.[xii] What could be an antiquarian project of constructing a genealogy of influence becomes rather a critique of the exhaustion of our social imaginary by economic speculation.[xiii] For the “sign of autumn” may have once figured a poet’s anxious stance towards predecessors. But today it names not only an anxiety in the face of finance’s power, but the consciousness of how the poetic act relates to the possible end of today’s economic system, of final-stage late capitalism in its lateness.

I. Voice (Flatus vocis)

Lerner is an undeniably intelligent bard of the digital age, whose recent writings offer a diagnosis of the increasingly belligerent tenor of our public discourse. His 2019 The Topeka School proleptically sketches the political consequences of our frenetic mediasphere, while his recent parable of the internet age, “The Hofmann Wobble,” asks what it means to write imaginative prose in an era in which contemporary literature and the information economy both depend on the discursive production of fiction.[xiv] His works of the last decade evince a “promethean anxiety”[xv] as to the perceived superiority of technology’s productive and creative—that is to say, poetic—capacities. Implicitly naming a literary dynamic, this anxiety is not simply directed at print literature’s uncertain place in the world of technical media (a facet of our media ecosystem that can be dated at least to 1900[xvi]), but at the fusion of finance and media particular to the past half-century of economic reforms. “Iridescent unregulated financial derivatives,” in Lerner’s words, are responsible for the “vast human poem” woven by today’s platform capitalism.[xvii]

Such platforms thus inherit the vision of a collectively laboring chorus envisioned by Bloom on the first page of his book proper: “Shelley speculated that poets of all ages contributed to one Great Poem perpetually in progress.”[xviii] We are far from a hermetic doctrine of poet against poet. The Lights asks what remains of poetry’s ability to shape collectivity (the implicit concern of Bloom’s above quote) in the face of the internet’s idée fixe of connectivity. “Imagine a song,” opens an early poem:

that gives voice to people’s anger. […] The anger precedes the song, she continued, but the song precedes the people, the people are back-formed from their singing, which socializes feeling, expands the domain of the feelable. (6)

In an age of rage and ressentiment, what generates collective forms of feeling is not poetry but the algorithms of social media so finely attuned to the mutual circulation of anger and profit.[xix] The poem remains uneasy about the potential for song being swallowed up by “talk” (6), the dizzying torrents of online chatter that found group identities through targeted feedback loops.[xx] The verb “socialize” rather impishly suggests that the social-democratic dream and the social-media nightmare are photographic negatives of one another.

The book’s third poem “Auto-Tune,” serves as an ars poetica for the whole. The title refers to the famous audio processing program used to correct the infringements of timbre and pitch once cherished as uniquely expressive elements of the voice.[xxi] The vocal frequency domain thus “signifies the recuperation of particularity by the normative” rather than Barthes’s “grain of a particular performance” (8). The verdict is delivered in an affectless prose whose line breaks coincide only too comfortably with punctuation. Instead of the age-old communitarian paradigms of sacred polyphony that unite individuals in a choral mass, Auto-Tune’s dumb mathematics sum up the world’s voices to produce the statistical illusion of human totality—in a single voice. The poet would like to occupy this position of enunciation, at once singular and collective, in order “to sing of the seismic activity deep in the earth and the | destruction of the earth for profit” (8). But the tweaked voice that could do so depends on the very computational logic that is today at the forefront of “permanent wars of profit” (11).[xxii]

This vocal bereftment is articulated in the language of influence. Lerner tries his hand at myths of priority. Caedmon, “the first poet in English” (8), discussed at length in his 2016 essay The Hatred of Poetry[xxiii], re-appears in “Auto-Tune” as one asked to sing “the beginning of created things”:

Here my tone is bending toward an authority I don’t claim

(“founding moment”),

but the voice itself is a created thing, and corporate; (9)

The reference to Cadmon is a mythologizing feign that allows Lerner to shroud the dilemma of technology’s monopoly on utterance in the garb of prophetic inspiration. Despair is re-cast as the hallowed origin of a poet otherwise riven by the stress of molestation and “authority”.[xxiv] For in the end, one “can only sing in a corporate voice of corporate things” (9). The pun has a way of truth about it. A better vision of collectivity is foreclosed upon if corporate control monopolizes the means and media to do so. If poetry can’t offer a vision of a better world, then all we are left with is “the sound of our | collective alienation” (10).

Not simply the voice but the breath that propels it returns throughout the collection as the medium of these “bad forms of alienated collective | power” (55): in the toxic waste of Fukuyama inhaled continents away (38, 55) or “all the beautiful conspiracies, which means ‘to breathe together,’ the ancient dream of poetry” (71). Social media’s conspiracies see to fruition what poetry could only fantasize. In The Hatred of Poetry, Lerner returns time and again to Whitman’s oneiric politics of an “I” that could serve as metonym for corporate fictions such as the nation or humanity. In the poetry, the problem returns as one of the medium. Lerner remains enthralled by a 50-second phonographic recording of Whitman reciting lines from his “America”:

what I miss most

is the distortion, noise of the wax cylinder,

the flaws in the medium that preserve

what distance it closes […]. (37)

The repetition of dis- in metrically proximate positions twice in three lines leaves a sonic trace such that “what distance it closes” stutters into “what distance it discloses.” Nostalgia’s love affair with distance is a kind of media effect because media bring us close to a given reality while also holding us at bay (the fate of celebrity images, Whatsapp voice notes from lost lovers, pornography, and Eucharistic adoration). Here, the media effect of nostalgia is a nostalgia for lost media effects. The distributed totality of poetic voice that Lerner dreams of through the Whitman recording is as chimerical as a longing for the phonograph in the digital age, or the living voice in the age of the phonograph. For all has been converted to bits of data anyway.

To hear Whitman’s voice, Lerner undoubtedly listened to one of the many recordings available on Youtube. Perhaps no such recording is more famous than the one found in a conversation between Paul Holdengräber and Harold Bloom at the New York Public Library, when Holdengräber plays the recording for an initially oblivious Bloom who only later realizes what he has heard: “Oh! That was the voice himself!” he exclaims, “Play it again.”[xxv] This primal scene of influence between the great theorist of the agon and “the voice himself”—did Bloom envision a capitalized V?—is shaped by medial conditions. Only fitting for the man whose memorious powers won him the popular image of “Literature, Incorporated” thanks to the medial metaphors of tape recorder and computer invoked in the endless string of articles hyping Bloom’s monstrous poetic recall.[xxvi] Indeed, Bloom found himself embroiled in his own anxieties of influence when, in answering his question “And what is Poetic Influence anyway?”, he was sure to distinguish his approach from the industry of “allusion counting […] that will soon touch apocalypse anyway when it passes from scholars to computers”. But Bloom’s anticomputational anatomy, like Lerner’s dream of a mass medium that could synthesize the masses, proffers figments of total vocal incorporation only to retract them through the spectral drift that recording technologies introduce into vocal presence. For technologies of inscription preserve authenticity on the condition of reproducibility. The a priori of the recorded lyric “I” reaching a collective audience is that it forfeits its status as authentic speech.

II. Lights (Influence)

Today, primordial scenes of influence do not involve the voice etched in the record but the cool blue-white of the laptop open to Youtube. The guiding trope of The Lights figures the prodigious effectivity of today’s culture of the screen—the TV, the smartphone, the laptop—in shaping communities, leveraging affects, channeling desires, fostering communication and crafting selfhood. Screens unite us in forms of greater or lesser sophistication, whether through network effects or the sheer fact that we’re all plugged in to an increasingly centralized mainframe.[xxvii] What is the place of poetry in today’s United States where Whitman is a recording (now watched, now heard) on Youtube and online influencers have arrogated to themselves the clout (and money) of the sorts that the literary ilk may once have earned?[xxviii] In a recent interview about the book, Lerner slinks towards an answer when asked about the collection’s persistent figuration of the lights as extraterrestrial contact. “Who or what are ‘the lights’?,” asks the reviewer, “Are they actual aliens? Muses? Ghosts?” Lerner replies:

All of the above. The lights are definitely the imagination of alien contact. In the title poem of the book, they are presented most explicitly as extraterrestrial. But it’s also about the human possibility of a certain kind of mis-reading—how we experience atmospheric effects or light pollution or whatever as a sign of possibility or mystery. Unexplained phenomena represent a kind of otherness or alterity, but then come back to us as just a way of understanding our own alienated version of the self or collective. Bad forms of collectivity can become a figure for collective possibility, an old and inexhaustible idea.[xxix]

We learn little that’s new here. The poems themselves reflect time and again on the warped perceptions and paranoid delusions fostered by online networks and the glowing screens that grant us access to them. Striking here, rather, is Lerner’s eminently Bloomian locution “mis-reading,” a gloss on “mis-prision,” which Bloom defines as “a misreading of the prior poet, an act of creative correction that is actually and necessarily a misinterpretation […] self-saving caricature […].”[xxx] Mis-prision is one of the many useful lies for parrying influence.[xxxi] Lerner’s imaginary of alien presences and ancient muses is a salvific etiology, a way of disavowing the fact that the lights are the screens and light pulses with which today’s poet must vie. This disavowal forms the flimsy pretext for reintroducing the Romantic language of (poetic) mystery or the MFA theoryspeak of ‘alterity’ in order to endow contemporary poetry with the hieratic sway of which fiber optic networks have dispossessed it.

Lerner’s response distances accordingly: the lights are not UFOs but rather “the imagination” thereof. Just as the imaginary of extraterrestrial contact is already a psychic displacement of our own collectivity, so is Lerner’s myth of alien contact a swerve away from the reality that digital infrastructures possess a near monopoly on crafting collectives. But just as…so clauses are, as every good high school literature student knows, rhetorical operations, which, it turns out, replicate at the level of figurative language a metaphoric operation inherent to computational technology itself.

I’m referring here to the manner in which the vast majority of us, civilians in matters of digital media, only have access to the ineluctable material infrastructures of fiber optic cables and computer hardware through the prosopopoeitic (>προσωποποιία, “to fashion a face, personify”) functions of the aptly-named interface. The reference of the eponymous “lights” slides from the “actual” pulses of light to the lit-up display of the screen on which are projected the metaphoric translations of computer processing. As Wendy Chun has argued, it is precisely the inaccessibility of the “Real” of computing that is responsible for the close link between fiber optics and paranoia.[xxxii] Re-formulating what Jameson first formulated as “cognitive mapping,” one could say that paranoia re-figures material processes as secret conspiracies in the same way that computers re-figure hardware as software.[xxxiii] The resulting “technical delusion” metaphorizes the relationship of media and power through an occult imaginary of spirits, flows, waves, aliens (in short: influences)—a representational process “deluded” because fictional, while also generative of the sorts of political delusion endemic to our conspiratorial Zeitgeist.[xxxiv]

Thus, Lerner’s anxiety of influence here is scarcely reducible to the dominance of new media over print or even the present-day forms of influence that threaten to outstrip the literary. Rather, it is in no small part the prodigious effectivity of these metaphorizing operations that challenges poetry on its own grounds. (Need we recall that at least as far back as Aristotle metaphor was considered the bread and butter of poetics?) It is with this in mind that we can read Lerner’s poetry anew, beginning with the title poem in which this luminescence is granted its faux-etiology:

At least the white poets might be trying to escape, using

the interplanetary to scale

down difference under the sign of encounter and

late in a way of thinking, risk budgets

the steal, the debates about face

coverings, deepfakes, we would scan

the heavens, discover what we’ve projected there

among the drones, weather events, secret programs […]. (14)

The hope that the singular white poet may speak for the body politic is ironized along with visions of the interplanetary.[xxxv] Extraterrestrial imaginings conveniently produce a humanity devoid of difference given that, from the perspective of the aliens, we are indeed a single race. In the wake of the January 6th attack on the U.S. Capitol Building, no one reading the fifth line can help but hear “The Steal,” another myth—facilitated by the media landscape—of alien invaders trying to seize power. (Who the aliens are depends on your party registration.) But against whom is the charge of belatedness levied? Is “late in a way of thinking” to be read in apposition to the poets who only now repurpose technical delusions as a literary technique? Or is it the commoditized “risk” traded in the form of personified light pulses (today’s form of personified capital) that are dismissed as epigones?

Literature and the internet uncannily resonate, as poetry anguishes over the influence of other media and the internet agonizes over the influence of anti-Semitic bogies, secret cabals. Both produce fiction: verse on the one hand, “deepfakes” vel sim. on the other. In 1973, Bloom insisted that “the meaning of a poem can only be another poem,”[xxxvi] his own swerve away from McLuhan’s pronouncement one decade earlier that “the ‘content’ of any medium is always another medium.”[xxxvii] McLuhan illustrated his claim on the example of “electric light [which] is pure information.”[xxxviii] Lerner’s “lights” level the difference between their competing sentences anyway.

For at the extreme, contemporary poetry is this mis-prision of literature’s impotence in the face of computers:

I came into the cities at a time when stray military transmissions

were confused for signs of alien life, a kind of poetry

I came into the cities at a time in which all but the poorest among us

had been colonized by blue light […]. (55)

But one need neither be an “intelligent” poet (the critical consensus on Lerner) nor possess an Eliotian idiom in order to employ aliens as a last-ditch effort to influence the public: all Orson Welles needed was a radio. In a now infamous 1938 CBS broadcast, Welles presented his adaptation of War of the Worlds. In the play’s carefully scripted opening sequence, an announcer “interrupted” the program to relay to listeners that alien troops had descended from Mars and begun their conquest of planet Earth. Panic ensued when a number of the listeners believed that Martians had indeed landed in Grovers Mill, New Jersey. Already in 1938, the test of literature’s enduring relevance was whether it could adapt to a new media format so as to leverage influence, where leveraging influence was defined as the ability to incite mass hysteria.[xxxix]

The transition from two-way wireless to one-way broadcasting formed the media-historical backdrop against which the War of the Worlds episode unfolded.[xl] From its advent, radio had been the object of popular fantasies of catching stray Martian transmissions. As radio transformed into a strictly receptive device for commercial programming from a select few companies, unease about the corporate control of this mass medium arose in turn. The paranoid reception of Welles’s broadcast thus figured the political economy of influence as an alien “invasion” in the homes and ears of the American listener, in part by reaching back to an imaginary of radio’s capacities prior to corporate control. In metonymically collapsing alien transmissions as a kind of poetry[xli], Lerner’s figuration follows the same arc in a different direction: he usurps for his art an effectivity akin to corporate-backed mass media. The efficacy of Welles’s extraterrestrial fable depended on a narratological metalepsis, a seeming intrusion of the extra- into the intradiegetic as the narrator “interrupts” this fictional program. Lerner’s collection proves to also depend on such a narrative legerdemain.

III. Money (Inflation I)

“THE DARK THREW PATCHES DOWN UPON ME ALSO,” (a quote from Whitman’s “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”) the longest and in some respects most significant poem of the collection, originally stems from Lerner’s unclassifiable 2014 work 10:04.[xlii] Part Four of the autofictional novel recounts the author’s residency in the city of Marfa, Texas, a cultural hub famous for the phenomenon of the Marfa lights. Believed to be atmospheric distortions of the headlights beaming across from Highway 67, the Marfa lights have been ascribed to an array of otherworldly phenomena, from UFOs to ghosts to errant spirits of the departed. Lerner the poet is keen to hold on to this “misapprehension” of “our own | illumination returned to us as sign” (36). What he terms a misapprehension is a process of re-estimation, the dumb medium of light now endowed with the significance, value, and meaning in which poetry transacts.

An allegory of influence emerges. For Bloomian misprision is fundamentally founded on a manipulation of values (“an ironical over-esteeming or over-estimation”[xliii]). Marfa’s light pollution and the static of Whitman’s recording, debris produced as technological side effects, here become the sources of poetic inspiration. Lerner’s quest for a medium of collectivity culminates in the ultimate fiction of value:

I deliver money to boys with perforated organs:

“unionism,” to die with shining hair

beside fractional currency, part of writing

the greatest poem.

[…]

the small sums

will grow monstrous as they circulate, measure:

I have come from the future to warn you. (33)

Much of the poem, like the 10:04 chapter from which it derives, is devoted to Lerner’s reading of Whitman’s 1892 autobiography “Specimen Days.” Of special importance is the scene in which Whitman darts through the wards of the Union wounded to leave behind “fractionals,” banknotes issued in place of the coinage that had fallen victim to currency speculation since the start of the Civil War. It is in this dissemination of money that Whitman comes closest to Lerner’s dream of fictionalizing a social body. “[W]riting | the greatest poem” is akin to investment, while the representative capacity of national currency serves as salve for the perforated bodies of the soldiery, metonymically: a body politic fractured by Civil War. Fear not that Whitman usurps his epigone’s task, for the contemporary poet rises up in admonishment in the final quoted lines: rampant inflation secures Lerner a victory, as poetic worth is measured in sheer number.[xliv] The voice from the future offers a poetic calque on influentia and its cognate inflatio. Indeed, our current use of the word “inflation” to mean the devaluation of currency derives from the monetary crisis of the Civil War, for which fractionals served as a stop-gap measure.[xlv] (Lerner terms it a time when “inflation rages” (30).) But since inflation’s inverse mathematics swell numbers while diminishing real value, we’re left wondering who exactly can be said in the end to possess the greater share of influence.

Both words ultimately derive from infl(u)are, to flow or breathe in(to), and carry with them an entire lexical field of currents, gusts, winds, and ultimately: specters, spirits and ghosts.[xlvi] According to the guiding conceit of the Marfa lights and the spectral projection that makes them possible, the poetry of The Lights is revealed to be but a secondary effect, like wave interference, produced by the circulation of money and its attendant inflated values. Just as these scenes of literary encounter with Whitman and other predecessors become imbricated in the dynamics of the credit economy, so too does the task of fictionalizing collectivity. In “Autotune,” Lerner’s ponderous “dream of a pathos capable of redescription, | so that corporate personhood becomes more than legal fiction” reveals him to be a careful reader of Ernst Kantorowicz’s The King’s Two Bodies. Among Kantorowicz’s exhaustive catalogue of corporate political fictions, we find his account of fiscus, the body of wealth and goods that figure the national body, a premodern precursor to today’s national treasuries. With the fiscus began a strand of political thought connecting corporatist metaphors with the circulation of money that ran through the veins of the body politic.[xlvii]

Poetic subjectivity’s constitution by the alien invasion of influence renders poetic personae dependent on porous passivity, that immoral seizure of the self that Wilde took to be the marring stain of influence.[xlviii] Like Whitman before him, Lerner retropes this passive “loafing”—which he defines in the corresponding passage in 10:04 as “a condition of poetic receptivity” (168)—as an active embrace shuttling between the one and the many. Being open to influence through one’s “perforated organs” becomes the sine qua non for the poetic production of the commons:

the almost-work of taking everything personally

until the person becomes a commons,

a radical “loafing” that embraces the war

because it also dissolves persons, a book

that aspires to the condition of currency. (36)

But the persistent figuration of poetry as monetary circulation warns us against reading for the intersubjective psychology of the Bloomian account. The classical desiderata of literary hermeneutics—assessing authorial subjectivity, qualitative influence (strong vs. weak poets), and semantic value—yield to an economy of social forms: personifications of the body politic, literature’s inflationary rhetorics, and the quantitative scaling-up of (internet) influence.[xlix]

When returned to its place within the narrative economy of 10:04, Lerner’s poem proves to be obsessively concerned with inflecting the the anxiety of influence towards the anxiety of inflation. Taken as a whole, 10:04 itself is organized by a plait of subplots. First, as Arne De Boever has amply reconstructed, the work is fixated on the financialization of the novel and the possible inflation of its value in the interstice between the virtual (the future novel for which Lerner receives a handsome advance) and the actual (the novel, 10:04, which we have in our hands).[l] Constructing “futures” through influence—a financial term to which Lerner returns time and again—extends to the second subplot: his attempt to impregnate his best friend Alex by various means. In accord with the ancient lexical field of influentia, the starry flux said to bear the immaterial soul was believed to be contained within the sperm. (The Latin word influxus named both the starry flux descending to earth and the act of insemination.) The final subplot concerns literary influence in the most literal sense, as the narrator hatches a plan to forge his own papers so as to sell his archive (at a premium) to a willing librarian.

Inflatio, influxus, influentia—three subplots each in some way organized around the financialization of influence, broadly conceived. The impregnation subplot is markedly queer, as we readers are left wondering whether the narrator’s “abnormal sperm” reaches its destination thanks to the wonders of financialized medicine (costly IUI treatments) or good old-fashioned sex, both of which he and Alex indulge in. “Biological and textual mortality”[li] are thematized in tandem, and the novel’s inflection of influence towards alternatively financial, biological and literary-historical senses probes narrative possibilities for fictionalizing the future beyond self-realizing market models. The late Mark Fisher, in his now epochal Capitalist Realism, made a compelling case for reading narratives of sterility in film and literature as a displaced “anxiety” of the inability to imagine a different future.[lii] Fisher invokes Bloom explicitly, whose poetic theory is based in the forging of genealogical relations between past, present and future through the medium of influence. Admittedly, Alex is not sterile; she becomes pregnant; a future is possible. The question is simply whether the obsessive talk of money grafted on the discussions of insemination means that the financial imaginary now completely dictates how that future may be envisioned.

Within the intradiegetic fiction of the text, all that the narrator produces upon his publisher’s advance is the poem “THE DARK THREW PATCHES DOWN UPON ME ALSO,” included in Lerner’s future collection The Lights. And though the narrator insists, “[n]obody is going to give me strong six figures for a poem,”[liii] Part IV, set in Marfa, is prefaced by an apodictic “Money was a kind of poetry.”[liv] What does it mean to inflate poetic value in this manner? Consider the textual history of the novel. Part III’s autofictional short story “The Golden Vanity,” rife with metaleptic intrusions of the narrator in his story, appeared first in the June 11, 2012 issue of The New Yorker, prefaced a day earlier by an interview in newyorker.com with the author(-cum-narrator?) Lerner about the interplay between self, author and narrator[lv], the very triad at play in this short story about an author forging his correspondence for money. The short story was subsequently included in this autofictional novel, organized around the same rebarbative triad of personae and devoted to recounting the writing of the very novel we have in our hands (10:04), within the frame of which all that is written is a poem (“THE DARK…”) published in Lana Turner Journal ahead of the novel and subsequently included in The Lights. Discourses on autofiction (which have shaped the reception 10:04 as much as The Lights) have tended to remain mired in moralizing plaints about narcissism.[lvi] But this refraction of writerly selves deserves, rather, to be understood as a function of how fiction is financed[lvii], how influence is inflated, in the contemporary literary market.

IV. Debt (Inflation II)

“Bundled debt” is Lerner’s choice phrase, repeated twice in the collection, for a form of society produced through money, one of “the bad forms of alienated collective power.” The imposition of financial policies since the 70s has led to a constitutive shift in the capital structure of social welfare, which no longer relies on interest-free state investment but rather the ruthless predations of financial markets. What facilitates this process is securitization, the transformation of debt into tradable assets on the market.[lviii] Securitization structurally shifts the risk of economic investments from private creditors and financial firms to state actors while, conversely, eliminating social services through austerity, privatization, and increasingly personalized indemnity. “Bundled debt” thus represents a kind of perverse contre-jour (the title of one of the poems on the Russian revolutionary Victor Serge) in which we find the image of our own socialized existence returned to us in the form of expropriated debt. Lerner manages to capture at the level of syntax the very ambiguity of the figure here in question (I cite again the lines quoted above):

late in a way of thinking, risk budgets

the steal, the debates about face

coverings, deepfakes, we would scan

the heavens, discover what we’ve projected there

among the drones, weather events, secret programs […]. (14)

One way of understanding the enjambed “risk budgets | the steal” is that the budget for risk in today’s debt economy is itself the steal (taken as predicate), the plundering of public wealth for the sake of a few private beneficiaries. According to the other reading, with its implied reference to the 2020 election, risk accounts for (“budgets” as verb) the public paranoia of “the steal” as an intrinsic part of how the financialization of debt and online media produce these deformed specters of society and its others. Together, economic deprivations are experienced by vast swathes of the disenfranchised American population as personal slights, a sense of being “owed” by elites, Communists, immigrants, Democrats, Jews, whomever “we’ve projected there.”[lix]

These lines rest on a delusional metaphorization of political economy into a paranoid panoply of figures (aliens, aura, waves), a process that could be traced back to the attempt to represent the otherwise unrepresentable hardware of digital technologies. Part and parcel of this metaphorization process is the re-figuration of predatory financial mechanisms (a material process) as the scheming of a secret cabal (a spectral undertaking), a process precipitated by recent developments in the economic sphere. For the fiscal orthodoxy regnant in recent decades figures class warfare as a neutral monetary policy, concealing economic machinations (a material process) beneath the necessary ghost of the “invisible hand” (a spectral undertaking). Post-Bretton Woods and, even more intensively, in the years following the 2008 crisis, the liberalization of credit through state treasuries has rendered monetary policy—most often under the pretext of combatting inflation—a feverishly politicized domain of financial decision-making. Inflation generates political delusion due to the delusional re-casting of austerity measures as apolitical, objective necessities.[lx] Of such concern to the modern poet is the manner in which bundled debt, risk, and currency—inextricably fused as they are with the digital media of today’s computer networks—are able to exercise an outside influence on the citizenry through this financial fabulation.

Thus the drama of influence staged in Lerner’s verse pits the poet not against the rival literary predecessor, as Bloom’s poetic agon would have it, but rather against the forces of finance. Bloomian agon here bends towards a political agonistics as theorized by Chantal Mouffe, who employs the term to name the interminable conflict of dissenting actors necessary for democratic participation.[lxi] Actualizing a political latency in Bloom’s theory, Lerner’s poetic agonistics stages the monopolization of the democratic sphere by capital personified. In opposing finance’s usurpation of the place of poetry, he agonistically opposes its usurpation of the space of democracy.

Lerner takes up this line of thought again in “The Circuit,” which opens with a fantasy of porous boundaries between flesh and light worthy of David Cronenberg. The dream of “hit[ting] the body | with a tremendous, whether it’s ultraviolet | or just very powerful light” is a verse arrangement of Trump’s April 2020 musings on the possibility of healing a body politic then ailing from the pandemic. Indeed, what passes for politics today is the passing of light through the body, from fiber to screen, screen to retina, corporate device to corporate collectivity. (Who knows this better than Trump and Musk?) The effulgent light of poetic influence is usurped. Fiber optic pulses can translate any media, any linguistic utterance, into the same form. Thus the late nineteenth century task of upholding semantic intractability against the language of the mass media is now defunct. Even if the poet offers a reboot of Mallarmé’s opposition to newspeak and writes in the language of today’s information systems—”malware | poets uploaded into language” (65)—the point remains that:

the fascist reaction and I

was mimetic of what I thought I opposed

with my typing […]. (66)

The singular “was” implies a singular subject, fascist reaction and lyric “I” now fused.

Poetic programs, modernist or postmodernist or neo-existentialist (“a new language of commitment” (66)) will not save us so long as any form of inscription is completely owned by a set number of conglomerates who dictate the terms of its circulation. Nothing short of seizing the means of poetic production will change the lyric landscape. The unholy marriage of fiber optic networks and financial markets issue in the birth of

the lightning-fast trades

of bundled debt, among the most beautiful phrases

in American English […]. (65)

Figured in this debt is not just the bundle of fibers that transmit securities traded on the market, but also what the poet owes in the drama of literary influence, his penury in the face of a technology that can craft the finest phrases.[lxii] Perhaps the last historic acts of writing were the paper blueprints on which Intel engineers sketched designs for the hardware architecture of the first integrated microprocessor.[lxiii] Today’s poet can only languish in nostalgia:

I want to make that sound

of setting something down

on paper as opposed to under

glass, ghostly opposition […]. (26)

When Lerner grafts the modifier “late in a way of thinking” onto his phrase “risk budgets” or describes how in today’s media ecology,

the book idles

In the chest, the new-old decadence

The fast-slow time of it

The arriving early to lateness (74)

the temporality that he is outlining is specific to the financial episteme under which we live. “[A]rriving early to lateness” articulates, in one fell swoop, anxieties about the fate of print media as well as a prescient definition of the financial markets that transact in securities and derivatives. Futures and options, two of the key assets traded in today’s economy, depend on a temporal involution by which the future is retroactively priced as a present-day asset.[lxiv] In Bloom’s genealogical saga, the temporality of influence functions in much the same manner, as paternity and primacy become negotiable, subject to refiguration. As Edward Said once described it: “The past becomes an active intervention in the present; the future is preposterously made just a figure of the past in the present.”[lxv] While his summary of influence’s labile tempo is particularly fitting, I cite Said because he had foregrounded (already in 1976) the historical and political dimensions of Bloom’s account, over and against its reduction to a rarified theory or closing exercises in canonicity.[lxvi]

In the above-cited interview with Hitzig, Lerner speaks of the “direct threat” to the “possibility of reception and transmission today” by the “debased rhythms and flattening and aggression of such ‘platforms’.” But the threat extends beyond the local anxieties of internet chatter to a felt impotency before the task of voicing collective demands, imagining alternative futures, and refusing the retreat of each into a private corner of rage. Luddism offers little succor. By the collection’s end, we find Lerner attempting to imagine what it might mean to recognize digital media as the sine qua non of our collective vision. Whitman’s omnivorous odyssey across Brooklyn Ferry and Crane’s mystical synthesis of America in The Bridge suddenly yield to a network of hyperlinks that recompose the organicity of the folk tradition (now composed of blue light):

the words of the song from and for the future I recorded on my phone in a common dream, for dreams are commons. The screen is badly cracked and I get glass in my finger every time I touch it. Something is lost in the transcription because it doesn’t have words, but room tone is gained, a sound bed is made. That’s why I’m sending my friends links: I want all my friends linked and listening as they fan out across the bridges until it is part of the folk tradition, the blue tradition, the wordless silent part I anonymously contributed by living. […] Its basic idea is that time can be defeated for an hour if everyone breathes together, but songs are not made out of ideas, they’re made out of glass, the aerosolized glass that damages performers. (112)

The cracked looking-glass becomes the precondition for (re-)finding totality. For when the screen breaks the illusion of interface is shattered and we are forced to come to terms with the dumb materiality in our hands. Lerner’s collection forces us to consider that which is repressed in order to produce the seamless spectacle of the lit-up display, alias, The Lights.

Peter Makhlouf is Lecturer in the Department of Comparative Literature at Princeton University. He has published widely in both academic and public-facing venues and is currently completing his first book on the decadence problematic in twentieth century German culture. His next book project explores the category of influence at the crossroads of poetics, media, and political economy over the past century.

[i] I cite from the excellent edition Hart Crane’s ‘The Bridge’, ed. Lawrence Kramer (New York: Fordham University Press, 2011), 4.

[ii] Transmemberment being the at once conjunctive and dissociative rhetoric integral to Crane’s poetic vision: see Lee Edelman, Transmemberment of Song: Hart Crane’s Anatomies of Rhetoric and Desire (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1987).

[iii] See the writings collected in Theodor Adorno, The Stars Down to Earth (London: Routledge, 1994).

[iv] For a readable introduction to the physical infrastructures of the internet see Andrew Blum, Tubes: A Journey to the Center of the Internet (New York: Ecco, 2012); on New York specifically see the fascinating little volume Ingrid Burrington, Networks of New York: An Illustrated Field Guide to Urban Internet Infrastructure (Brooklyn: Melville House, 2016).

[v] On the latest chapter, see https://www.wsj.com/articles/high-frequency-traders-push-closer-to-light-speed-with-cutting-edge-cables-11608028200

[vi] https://www.popularmechanics.com/technology/infrastructure/a7274/a-transatlantic-cable-to-shave-5-milliseconds-off-stock-trades/

[vii] https://www.verizon.com/about/news/critical-steps-completed-bringing-fiberoptic-connectivity-lower-manhattan

[viii] See Abraham Bos, The ›Vehicle of the Soul‹ and the Debate over the Origin of this Concept,” Philologus 151, (2007), 31–50.

[ix] Ben Lerner, The Lights (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2023).

[x] It has, to my view, never been noted that Harold Bloom’s epochal The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry (New York: 1973) appeared in that annus horribilis of 1973, which fell under the influence of an ominous star. Oil shocks rippled through the developed world; the collapse of the Bretton-Woods agreement spelled the end of the gold standard; and the industrial boom of the postwar period finally sputtered to an unprofitable end. The US economy’s transition from industrial to financial capital was well underway, facilitated by the Black-Scholes equation for derivatives trading which appeared in print in the same year. So began the epoch that Ernst Mandel in his 1972 book would term Late Capitalism. Though no one foresaw this conjuncture, Bloom’s concept of “influence” would go on to play a defining role in the financial markets and digital media that were, in 1973, just beginning their precipitous rise. The fullest account of the significance of 1973 in financial history may be found in Mikkel Frantzen, “1973: A Monument to Radical Instants,” in The Birth of the Financial Thriller: Making a Killing in the 1970s (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2024).

[xi] See Cédric Durand, Fictitious Capital: How Finance is Appropriating Our Future, trans. David Broder (London: Verso, 2017).

[xii] For the most thoroughgoing study of this theme, see Ben Hutchinson, Lateness and Modern European Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[xiii] My aim is thus neither to seek new digital tools for the study of influence nor to trace the shifts in literary form born of the pressures of new media. For the most concerted attempt to take stock of this new media landscape, see Alan Liu, Friending the Past: The Sense of History in the Digital Age (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018).

[xiv] Ben Lerner, The Topeka School (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2019); Ben Lerner, “The Hofmann Wobble: Wikipedia and the assault on history,” Harper’s Dec. 2023, 23-32.

[xv] Hannes Bajohr,”Algorithmic Empathy: Toward a Critique of Aesthetic AI,” Configurations 30 (2022), 203-31, cites this term as an expression of human’s alienation in the face of technologies’ superior creative powers and thus, implicitly, as a literary dynamic emerging from the anxieties of technology’s perceived poetic capacities.

[xvi] According to Friedrich Kittler’s account in both Discourse Networks 1800/1900, trans. Michael Metteer, with Chris Cullens (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press: 1990) and Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press: 1999).

[xvii] “The Hofmann Wobble,” 30

[xviii] Bloom, Anxiety of Influence, 19.

[xix] See Joseph Vogl, Capital and Ressentiment: A Brief Theory of the Present, trans. Neil Solomon (London: Polity, 2022).

[xx] See Brian Judge, “The birth of identity biopolitics: How social media serves antiliberal populism,” New Media & Society 26/6 (2024), 3273-89.

[xxi] On the history and cultural politics of autotune see the excellent essay by Simon Reynolds, “How Auto-Tune Revolutionized the Sound of Popular Music,” https://pitchfork.com/features/article/how-auto-tune-revolutionized-the-sound-of-popular-music/.

[xxii] See Justin Joque, Revolutionary Mathematics: Artificial Intelligence, Statistics and the Logic of Capitalism (London: Verso, 2022).

[xxiii] Ben Lerner, The Hatred of Poetry (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2016).

[xxiv] On molestation and authority in the endeavor to found a literary beginning, see Edward Said, Beginnings: Intention and Method (New York: Columbia University Press, 1975).

[xxv] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YWi0AMyniYc, 4:33f.

[xxvi] See Marc Redfield, “Literature, Incorporated: Harold Bloom, Theory, and the Canon,” in Theory at Yale: The Strange Case of Deconstruction in America (New York: Fordham University Press, 2016), 103-124.

[xxvii] See Benjamin Bratton, The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015). In her “Common Sensing? Machine Learning, ‘Enchantment’ and Hegemony,” New Left Review 144 (Nov/Dec 2023), Hito Steyerl probes how tech companies are carrying out data mining operations in the Global South in order to rope populations worldwide into new financial networks that wed blockchain to AI.

[xxviii] On the economics of influence see Emily Hund, The Influencer Industry: The Quest for Authenticity on Social Media (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2023).

[xxix] “Ben Lerner in conversation with Zoë Hitzig,” November (2023) https://www.novembermag.com/content/ben-lerner.

[xxx] Anxiety of Influence, p. 30

[xxxi] On the logic of lie and metaphor effected by the finance economy see Amin Samman, “Capital of Lies” in boundary2online, Special Issue: The Gordian Knot of Finance (Dec. 2024), https://www.boundary2.org/2024/12/amin-samman-capital-of-lies/.

[xxxii] On the dialectic of fiber optic enlightenment see Wendy Chung, Control and Freedom: Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005).

[xxxiii] Fredric Jameson, “Cognitive Mapping,” in Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg (eds.), Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1988).

[xxxiv] Jeffrey Sconce, The Technical Delusion: Electronics, Power, Insanity (Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2019); on the poetics of paranoid ideation, i.e., the way in which paranoid politics depends on the work of imaginative creation, see Zahid Chaudhary, “Paranoid Publics,” History of the Present 12/1 (2022), 103-126.

[xxxv] A theme that returns in The Hatred of Poetry.

[xxxvi] Bloom, Anxiety of Influence, 95.

[xxxvii] Marshall McLuhan, “The Medium Is the Message,” in Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1964), p. 8.

[xxxviii] ibid.

[xxxix] For the relevant texts, see John Gosling, Waging the War of the Worlds (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2009); for a study of the event, see Brad Schwartz Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News. (New York: Hill and Wang, 2015).

[xl] I follow here the account offered by Jeffrey Sconce, “Alien Ether,” in Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000), 92-123.

[xli] Note the ambiguity of “a kind of poetry” referring to either “signs of alien life” or “stray military transmissions” or the metaphoric process whereby the latter is translated into the former.

[xlii] Ben Lerner, 10:04 (New York: Picador, 2014).

[xliii] Bloom, Anxiety of Influence, xiii.

[xliv] A theme famously explored by the poet-turned-hedge-fund-employee Katy Lederer in The Heaven-Sent Leaf (Rochester, NY: BOA Editions, 2008).

[xlv] This is also the period when the term “fictitious capital” emerges in England; see Durand, Fictitious Capital, p. 41f.

[xlvi] See Rainer Specht, “Einfluß,” in Historisches Wörterbuch der Philosophie online, https://doi.org/10.24894/HWPh.793.

[xlvii] Ernst H. Kantorowicz, “Christus-Fiscus,” in The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology (Princeton: Princeton University Press 2016 [1957]), 164-92; cf. 342-346. Cf. Gerhard Scharbert and Joseph Vogl, “Zirkulation, Kreislauf,” in Joseph Vogl and Burkhardt Wolf (eds.), Handbuch Literatur & Ökonomie (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2019), 347-51.

[xlviii] Early in The Picture of Dorian Gray, Lord Henry Wotton declares: “There is no such thing as a good influence, Mr. Gray. All influence is immoral – immoral from the scientific point of view. […] Because to influence a person is to give him one’s own soul.”

[xlix] Franco “Bifo” Berardi has laid the groundwork for a critical theory of finance poetics in his The Uprising: Poetry and Finance Capital (Los Angeles: semiotexte, 2013).

[l] Arne De Boever, “Financing the Novel: Ben Lerner’s 10:04,” in Finance Fictions: Realism and Psychosis in a Time of Economic Crisis (New York: Fordham University Press, 2018), 152-180.

[li] Lerner, 10:04, 55.

[lii] Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Winchester, UK: zero books, 2009), 3.

[liii] Lerner, 10:04, 137.

[liv] Lerner, 10:04, 158.

[lv] June 10, 2012: Interview with Cressida Leyshon (https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/this-week-in-fiction-ben-lerner).

[lvi] For a recent example, see Rhian Sasseen, “Extremely Online and Incredibly Tedious,” The Baffler, June 12, 2024: https://thebaffler.com/latest/extremely-online-and-incredibly-tedious-sasseen.

[lvii] Something also highlighted in De Boever, “Financing the Novel.”

[lviii] On these developments see Maurizio Lazzarato, The Making of the Indebted Man (Los Angeles: semiotext(e), 2012).

[lix] On the structural relationship between finance and political paranoia, see Fabian Muniesa, Paranoid Finance (Cambridge (UK): Polity, 2024).

[lx] On this point see the two important recent contributions of Paul Mattick, “From the Great Inflation to Magic Money,” The Return of Inflation: Money and Capital in the 21st Century (Cornwall: Reaktion, 2023), 121-46 and Stefan Eich, “Silent Revolution: The Political Theory of Money After Breton Woods,” in The Currency of Politics: The Political Theory of Money from Aristotle to Keynes (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2022), 177-205.

[lxi] See Harold Bloom, Agon: Towards a Theory of Revisionism (New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982) and Chantal Mouffe, Agonistics: Thinking the World Politically (London/New York: Verso, 2013). On the necessity of contestation in opposing the anti-democratic nature of contemporary monetary politics see Stefan Eich, “Democracy and the Political Limits of Monetary Politics,” boundary2online, Special Issue: The Gordian Knot of Finance (Dec. 2024), https://www.boundary2.org/2024/12/stefan-eich-democracy-and-the-political-limits-of-monetary-politics/.

[lxii] On the implications of computer code for print media see N. Katherine Hayles, Postprint: Books and Becoming Computational (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021).

[lxiii] On this point see Friedrich Kittler, “There Is No Software,” in The Truth of the Technological World: Essays on the Genealogy of Presence, trans. Erik Butler (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2014), 219-229.

[lxiv] On transactions between poetics and economy in the wake of financialization see Joshua Clover, “Retcon: Value and Temporality in Poetics,” Representations 126/1 (2014), 9-30.

[lxv] Edward W. Said, “The Poet as Oedipus,” (a review of Harold Bloom, A Map of Misreading), NY Times Book Review, April 13, 1975.

[lxvi] See “Interview: Edward W. Said,” Diacritics Vol 6 no. 3 (1976), 30-47.