Palestine, Israel, and the Problem of Naming

Oded Nir

Problems of naming are many times seen as moral issues: we try to fix a bias hardcoded into the way we write or speak by inventing new names for people and things. But names are also historical problems disguised as simple words, problems that are sometimes much more intractable than what can be fixed by naming itself. I would like here to offer a brief example for the problem of naming which recently plagues any mention of Palestine and Israel in writing on the left: that slight hesitation, about whether to write “Palestine”, “Israel/Palestine”, or some other combination. One tends to swallow that hesitation and move on to whatever one had been planning to write. But this is clearly a case of repression, of however minor a kind. The act of naming in this case threatens to open up a hornet’s nest: a host of narratives and ideological positions that don’t quite fit what one means to say. The name one chooses seems constantly in danger of failing to capture its object—a kind of approximation that ends up letting what it names slip away.

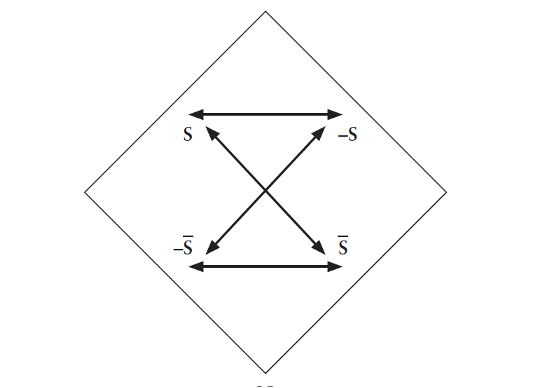

I use here the Greimassian rectangle, as Fredric Jameson and Phillip Wegner developed it, to propose a structure for thinking about this problem of naming “Israel-Palestine”. The Greimassian rectangle allows us to think of binary oppositions as opening up to include two kinds of negation: A primary one, in which one term is the strong, determinate negation of its opposite; this kind of opposition operates between our initial two terms. And a second negation for each one of these terms, a weaker and more general one, that indicates what is simply not-it. In the following diagram, S and -S designate the initial two terms; while the terms designate, diagonally, the weaker negations of each of the initial terms of the opposition:

At its best, the Greimassian rectangle can help us discern the structure of categories that underpin a narrative or discursive scene. This discerning does not necessarily solve anything, but should help us formulate new problems and redefine situations. To do that, the terms of the initial opposition and their weaker negations must be polyvalent enough to generate different kinds of synonyms and opposites.

Here I would like to plot the different, common enough, possibilities for naming “Israel/Palestine” on the square. It should be emphasized that there is nothing frivolous about using the square in the context of an urgent political problem. Political urgency should never trump thinking. The last few years surely teach us that there is nothing obvious about how to fight rising fascism or how to overcome the liberal capitalism from which the former emerges (and with which fascism entertains deeper affinities, as Adorno and Horkheimer argue in Dialectic of Enlightenment). And to repress thinking with moralization doesn’t seem like a useful option either. My use of the square here is an attempt to think through a political situation; maybe it is a failed attempt, but there is nothing frivolous about the effort itself.

As a point of departure, each one of these name-combinations for Israel/Palestine should be seen as a historical narrative in reified form. To turn a name back into a narrative means to be able to see it as self-contradictory, or as having a gap or discontinuity at its core. The Greimassian rectangle’s power resides precisely in that it operates somewhat like Walter Benjamin’s constellation: the seemingly arbitrary process of contrasting different names, as if they were external to each other, ends up exposing each name’s internal contradictions. That said, to narrativize each term is not just to recount the history of its use. The task, rather, is to eke out the narrative that each term seems to insinuate in the current situation. Teasing these out is a matter for intuition, an operation that remains outside any empirical verifiability, though it may be complemented later with a more dialectical form of historical inquiry, in which terms come to take on retroactively different meaning as time moves and paradigms shift. Insofar as each name will come to designate a narrative form, this is where History, and futurity, will be articulated with all their urgency.

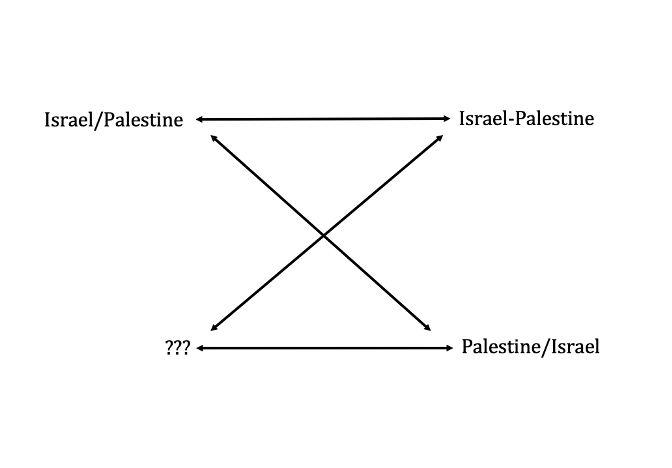

For the initial opposition, I suggest we take the two names “Israel/Palestine” and “Israel-Palestine”. What distinguishes these is only the difference between a separator and a hyphen. But this small change designates a crucial difference of historical and narrative relationship. “Israel/Palestine”, I think, designates today a narrative in which an antagonism is affirmed between Israel and Palestine. Palestine is here narrated as Israel’s other, some resistant element to it, while Israel itself is seen as a positive geopolitical unit. This antagonism may be regarded as either external, with Palestine constituting some external threat, or as internal, with Palestine serving as constitutive aberration, the “concrete universal” exception to Israel, on which the latter’s wholeness actually depends. Here belong both Golda Meir’s paradoxical “there is no such thing as Palestinian people”, and, on the more literary side, Amos Oz’s early stories, in which the Kibbutz is spatially threatened by external Palestinian presence.

As its opposite, “Israel-Palestine” is where the antagonism between the two is either denied or reconciled (after its assertion), in favor of a flat equivalence or continuity, either in an idealistic-humanist terms or in some cynical assertion that national difference is mere illusion. This continuity and equivalence is an important element in the horizon of the Oslo and 1990s peace process, in which, of course, the hope for peace was unfortunately constructed through a completely uneven (future) arrangement: the establishment of a Palestinian state subservient to Israel. Negativity itself is banished here: the continuity and equivalence are asserted immediately, with no labor of negation. Here belong, as well, sundry humanistic pronouncements on the “Israeli-Palestinian” conflict, ones whose explicit or implicit message is general regret over the loss of life and an ideological commitment to “balanced perspectives”—which, of course, is another name for supporting the status quo. This continuity between or equivalence of “Israel-Palestine” is politically shunned today on the left, as some well-meaning but ultimately misguided and thoughtless lip-service to peace.

These, then, form our initial opposition, in which an initial recognition of antagonism is replaced by arbitrary equivalence. The third term will then also be a negation of the first term, “Israel/Palestine” (diagonally represented in the square), but a more general one, designating what is simply not-it. I would like to suggest the name “Palestine/Israel” for exactly this term. It may seem like a simple transposition, in which the terms just switch places around the divider, which still affirms the antagonism between them. But the order here matters qualitatively, and neither “Palestine” nor “Israel” in “Palestine/Israel” mean the same thing as they do in “Israel/Palestine.” What “Palestine/Israel” invokes, I think, is a narrative in which Israel is a contingent, historical imposition on a preexisting Palestine. But Palestine here does not immediately designate an existing geopolitical entity, on which political scientists can wax boringly. Rather, it opens up the way to imagining a past collectivity that must impossibly be recovered, or a speculative collective project to come, free from external oppression. Meanwhile, Israel in this option is not some internal exception, but an external imposition, a dominant and oppressive one. This is the place of the colonial or settler-colonial narrative, in which the settler’s eliminationist tendencies must be defeated at all costs, as a precondition for any recovery of collectivity. Thus, we get the following basic square:

Once we place these options in the rectangle, what becomes clear is that there is one corner that remains yet unnamed: the bottom-left one. This fourth narrative option is the one that, for Jameson and Phil Wegner, is reserved for the Hegelian negation of the negation. It cannot be determined simply by a logical procedure out of the other three names, which are relatively easy to isolate, as Jameson notes. Positing it requires an imaginative leap and a wager of thought. It is a term that is not only the general negation of “Israel-Palestine” but also of the imaginative space opened up by the other two names: it is impossibly self-contradictory and unstable. In the context of our square, it is a term that requires something like a negation on two fronts: it subtracts itself from the easy continuity of “Israel-Palestine”, but it also refuses both the splitting of Palestine from Israel, or the past or future projection of a whole Palestine, free of Israel.

I want to suggest that what names this fourth option is to be found in our relationship to the aftermath to the horrible events of October 7, 2023. That these have come to mark in our symbolic order some decisive shift, some end of a previous status quo (itself hideously oppressive to Palestinians), should be clear enough, even if the precise contours of a new narrative have not yet fully emerged. One can see the signs of this potential shift in our responses to the new situation. The student encampment movement is a good example: its emergence seems to mark some new imaginary relationship to Palestinian struggle and Israel, the uncompromising demands for decolonizing Palestine and US institutions now seem to hold some stronger, more direct possibilities for identification. Institutional responses to these new challenges also seem to have something new about them: the crackdown on the protesters, the suspicion that any criticism of Israel is somehow antisemitic—a suspicion not dispelled by insistence on the difference between the two—all attest to the emergence of some new allegorical structuring to the events in our imagination (their signifying of something more than just themselves). Intellectual responses within the left also seem to signal some new situation waiting to be named, insofar as they waver between a condemnation of the Palestinian attacks and of the Israeli response, to a doubling down on an established narrative of anti-colonial struggle, itself borrowed from mid-20th century struggles. What I argue below is that the contradictory historical options opened up by this newness are the ones that inspire in us simultaneously both genuine hope and terrible fear: on the one hand, the symbolic revival of the possibility of Palestinian—and universal—liberation invoked by the October 7 attacks, expressed for example in Jodi Dean’s commentary. And on the other, the genocide of Palestinians by Israel, already underway, and the stemming of all hope for Palestinian liberation; but also the genuine Israeli or Jewish fear of elimination (unjustifiable, perhaps, but a real fear even so).

Thus, “The aftermath of October 7” comes to designate, impossibly, both negations that I mentioned: it decisively subtracts from the list of available categories the flat, unproblematic, continuity or equivalence of “Israel-Palestine” – the very antagonism (the Palestinian attacks or the genocidal Israeli response) cannot be plausibly contained in some notion of “business as usual.” But on the other hand, “October 7” also takes its distance from “Israel/Palestine” and “Palestine/Israel”: overt Israeli eliminationist glee towards Palestinian suffering cannot possibly anymore designate a repressed, Palestinian, “concrete universal” exception to supposedly universal Israeli law; it is instead Israel’s retreat into unapologetic particularism. Meanwhile, the celebration of the October 7 attacks threatens to collapse into an eliminationism of its own: misgivings about the emancipatory horizon of Hamas and about the denial of Jewish self-determination, and hesitation over whether to support of the attack itself—all of which mark the current moment’s distance from the “Palestine/Israel” option. Thus, “October 7’s aftermath” is, if anything, a figure for insistent negativity, one to which the previous names have trouble adhering. In other words, it is a textbook eruption of the Real into the Symbolic.

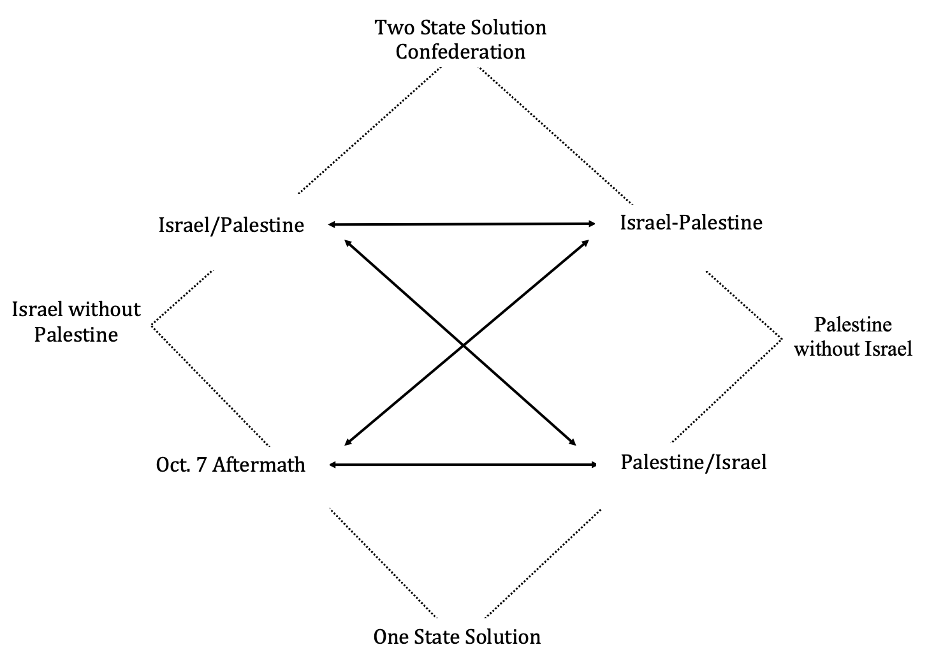

But what can this eruption mean? Since a new symbolic code has yet to emerge, the answer to this question requires us willfully to arrest the play of synonyms that fuels any process of naming—requires, indeed, that reification be allowed to take hold again, but hopefully in a novel and suggestive way, making concrete some new Historical horizons. Thus, as a way of answering this question, I return to the rectangle. So far, I’ve only charted the internal terms of the rectangle. But it offers us four other positions, external ones, as my initial chart discloses. These four external options allow us to position different combinations of the four initial terms, as contradictory as these initial terms may seem. And so I would like to suggest the following full Greimassan rectangle:

Of particular importance in this chart is the status of the top and bottom terms, called the complex and the neutral term, respectively. The top term is reserved for the operation of ideology: the imagined reconciliation of contradiction (a formulation that has its roots both in Levi-Strauss and Althusser). This is where “Israel/Palestine” and “Israel-Palestine” find their symbolic reconciliation: admitting a historical antagonism between Israel and Palestine, but asserting too quickly and idealistically the possibility of their equivalent coexistence as separate states. This is precisely the imagined reconciliation of the 1990s failed peace effort, which still functions as some hollow “common ground” to signal peaceful intentions. It is clear, today, that such splitting into two states is not really possible any longer, considering Israeli land theft, and that its implicit content is nothing but a formalization of a relation of subordination of Palestine to Israel—as it did back in the 1990s. That today world leaders can overtly express their support for the peace of a two-state solution, yet directly contribute to Israeli oppression, is perhaps the best demonstration of this position’s quintessentially ideological function.

But a new option has recently emerged to occupy this reconciliatory position: the confederation, which has gained some support in recent months. The confederative solution, in its many variants, seems to be even a more effective reconciliatory (or ideological) option than the two-state solution. The way core issues are addressed—territory, the Palestinian right of return and reparations, the degree of Palestine’s independence, etc.—is immediately revealed to be no different than how they’re imagined in either a two-state or that option on which I haven’t touched yet, that of the one-state framework (as for example in one variant’s positing of an open border, which is borrowed from the one-state paradigm, but with each state deciding on the differential rights of the various groups in its territory, which again returns us to all the familiar problems of the two-state solution). The confederation’s main novelty seems to reside in the establishment of a common governmental order, which in fact becomes its sole characteristic in the documents of The Israeli Palestinian Confederacy.[1] [2]

Here, only the coordinating governmental order is elaborated in a proposed constitution, and engagement with any important disagreements is refused and deferred to the future. Here, then, we have nothing but the last turning of the screw of an eternal present, extending from the oppression of Palestinians into what was supposed to end it—peace negotiations. To put it bluntly, in this confederated non-solution, we are permitted to have the dessert of eternal oppression as long as we eat the heaped up greens of eternal negotiation—the governmental institutions of the confederation.

But perhaps the biggest problem with the proposed confederation, one not addressed by any of its adherents or critics, is the absence in it of what Jameson calls collective feeling or Ibn Khaldun’s asabiyya: federalism “does not seem to work as a concept, as a value. Perhaps it still carries a little too much of the atmosphere of tolerance and altruism and too little of a vital narcissism to be viscerally attractive.”[3] In An American Utopia, Jameson offers a more sustained discussion of federalism as a solution and a problem in its own right, thematized precisely as one of envy and the theft of jouissance (which is just another way to get at the absence of collective feeling). He then offers a Fourieresque “non-solution” for it: the “Psychoanalytic Placement Bureau,”[4] which allows for people to chance occupations and forms of life as well as absorbing of therapy, both individual and collective, into a centralized state apparatus.[5] Yet, such an ambitious centralized supplement to federalism is precisely what is barred in Palestine/Israel confederation proposals, in positing differential rights of residents and citizens. My point here is that to the degree that one is able to imagine libidinal investment in a confederation (as a properly utopian narrative might do), it would become indistinguishable from the truly Utopian possibility, both threatening and promising, haunting our ideologues today: that of the single-state solution. The speculative rise of a different “collective feeling,” then, immediately implies a commonality of fate that today is still hard to imagine except as a single nation-state.

But before I address this option, which appears in the bottom corner of the outer square, a few words are in order about its outer left and right corners: “Israel without Palestine” and “Palestine without Israel.” One should remember here that “Israel” is not identical to “Israel without Palestine”: to mark an absence is itself a presence in the latter case. The latter differs from the former in that it introduces the exclusion of Palestine into the very notion of Israel. Such barring of Palestine is clearly a solution of sorts for the combination of “Israel/Palestine” and “October 7 Aftermath”: the continued genocide of Palestinians—murderous oppression, slow or fast, of a kind that no longer pays even symbolic homage to a just, peaceful, resolution, becomes part of what Israel means. It signifies the eradication of the Palestinian “exception” to Israel, implied by Israel/Palestine. Trump’s “peace plan,” which includes the barbaric intention of the forcing Palestinians into exile from Gaza, also belongs in this outer right corner.

But the opposite corner, that of “Palestine without Israel” as the combination of “Israel-Palestine” and “Palestine/Israel,” is less self-explanatory. This possibility may be counterintuitive, since it operates through a different valence of the equivalence asserted by “Israel-Palestine.” (In passing it should be noted that such switching of valences takes place in any Greimassian square worth its salt). Here, instead of the too-quick equivalence of an unjust peace, equivalence designates an equivalence of struggle, borrowed from the underlying materialism of “Palestine/Israel,” in which what is insisted upon is Israel’s continued “struggle” against the very existence of Palestine. The equivalence is then an assertion of continued struggle against Israel as such, when we see the latter’s entire existence as one predicated on the oppression of Palestine. Hence we get “Palestine without Israel”: the refusal of Israel’s “right to exist” or even the use of its name.

But the most interesting option is the bottom corner of the square, usually called the neutral term. Here, one is no longer dealing with a reconciliation, but with an uneasy shifting between irreconcilable options, which is identified by Jameson as the Utopian itself, and by Wegner as an equivalent of the Lacanian Real. The Utopian—“solutions without problems”—is the place of the possibility of a single state: that still hard-to-imagine, both material and ideological, decolonization of Israel (a cultural revolution would be the precise term here). It spells the symbolic end of Israel as such, already predicted by Ilan Pappe, Shir Hever, and others;[6] but at the same time, impossibly, it spells the end of a future return to indigeneity, as well—to a whole, self-identical Palestine. It weakly promises Palestinian emancipation without an independent Palestine; but also Jewish self-determination without a state predicted on Jewish exceptionalism. To be sure, the one-state solution poses a challenge to our imagination, challenging our ability to construct something new while simultaneously flushing out the limitations of what we can currently imagine. As a properly Utopian term, all existing historical tendencies seem to work against its realization, making far more likely that the sharpening contradictions collapse this Utopian possibility into one of its horrific doppelgangers: the fascist Israeli right’s “Greater Israel” vision,[7] in which not only does the genocide of Palestinians continues, alongside the annexation of Palestinian territory, but Israel seizes territory from adjacent countries, as well.

Maintaining’s one’s fidelity to the Utopian option of a One State has another name: a belief in a communist collective horizon, and its necessary insistence on a confrontation with the capitalist system that conditions the current situation in the aftermath of October 7 (a proposition that I will not be able to defend here). If there is a final referent to our response to the eruption of the Real on October 7, it can be speculatively identified with the sudden appearance of the anxieties produced by life under capitalism, overlaying the violent events and investing them with our most intimate fears. Whether such sudden eruption can turn into a revolutionary political program—whether it becomes a genuine Event—is still to be seen. It should be insisted that one should not forsake this horizon because of the general anti-utopianism that still has its ideological chokehold over our collective imaginations. Rather, we live in a time in which what was considered ideologically impossible until recently can suddenly become real options again (the global rise of authoritarianism, but also of flashes of socialist politics, are obvious examples). Thus, to insist on this utopian horizon is to take part in this slow, hesitant and anti-anti-utopian trend.

Oded Nir is the author of Signatures of Struggle, a 2018 book on “the figuration of collectivity in Israeli fiction.” He has edited volumes on Marxist approaches to Israel/Palestine and on the literatures of the capitalist periphery. He teaches courses on Israeli culture and literature at Queens College.

[1] “Israeli Palestinian Confederation Mission Statement,” Israeli Palestinian Confederation, accessed March 19, 2025, https://ipconfederation.org/mission/.

[2] https://ipconfederation.org/

[3] Fredric Jameson, Allegory and Ideology (London; New York: Verso, 2019), 195.

[4] Fredric Jameson, An American Utopia: Dual Power and the Universal Army (London; New York: Verso, 2016), 81.

[5] Jameson, 82–85.

[6] Ilan Pappe, “The Collapse of Zionism,” Sidecar (blog), June 21, 2024, https://newleftreview.org/sidecar/posts/the-collapse-of-zionism; Shir Hever, “The End of Israel’s Economy,” Mondoweiss, July 19, 2024, https://mondoweiss.net/2024/07/the-end-of-israels-economy/.

[7] Qassam Muaddi, “Inside ‘Greater Israel’: Myths and Truths behind the Long-Time Zionist Fantasy,” Mondoweiss, December 17, 2024, https://mondoweiss.net/2024/12/inside-greater-israel-myths-and-truths-behind-the-long-time-zionist-fantasy/.