Fig. 1. Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow. Bantam, 1974.

This article is part of the b2o: an online journal special issue “The Question of Literary Value”, edited by Alexander Dunst and Pieter Vermeulen.

Understanding Literary Value Requires Institutional Ethnography: The Case of Pynchon’s Pulitzer Scandal

Günter Leypoldt

Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow appeared in March 1973 and was soon nominated for both the National Book Award (NBA) and the Pulitzer. This may seem unsurprising in hindsight, but during the 1970s the still evolving system of prizes had not always been that open to such hard sells (“One of the Longest, Most Difficult, Most Ambitious Novels in Years”, the New York Times had titled its review [Locke 1973]). When the Pulitzer advisory board overruled the jury’s selection of Gravity’s Rainbow and paused the prize for the year, the scandal that followed in May 1974 reveals important changes of literary authority in the post-45 period. In what follows, I chart these changes and propose that in order to understand the making of literary value, we need to practice some socio-institutional ethnography. To that end, I define varieties of value, consider questions of relevance or “impact”, and distinguish ethnographers from critics.[1]

Gravity’s Rainbow became prizeworthy to the degree that the jury culture during the 1960s saw a subtle but consistent orientation towards academic peer review. The recent history of the NBAs makes this trend visible: founded as a book industry prize in 1936, its early selection committees included book traders and industry professionals that kept winners close to mainstream tastes (in 1937, the prize for most distinguished novel went to Gone with the Wind). With the more academicized literary culture of the 1960s, the nomination and consecration process came to be dominated by credentialed experts (prize-winning novelists, literary journalists, and academic critics). Book industry professionals tried to reverse this trend with a number of largely unsuccessful rear-guard actions. In 1970, for example, the National Book Committee introduced a nationwide poll that gave booksellers a vote in the nominations, a measure that ended badly when the 1971 poetry and fiction juries refused to consider the bookseller selections (Raymont 1971). The poll was abolished, and subsequent juries gave the NBA to John Barth’s Chimera (1973), Gravity’s Rainbow (1974), and William Gaddis’s J R (1976), hard pills to swallow for an already grumbling book industry.

The Pulitzer forced these tensions into the open because it required decisions to be ratified by its advisory board. So when the jury of three scholars—Alfred Kazin, Elizabeth Hardwick, and the Amherst English professor Benjamin DeMott—selected Gravity’s Rainbow, the board’s 14 newspaper executives and University of Columbia trustees overturned it as “‘unreadable’, ‘turgid’, ‘overwritten’, and in parts ‘obscene’” (Kihss 1974, 38).

Cultural historians channeling their inner critic might dismiss the Pulitzer board as a ship of fools, philistines too obtuse to recognize Pynchon’s greatness (the New York Times suggested they “should take a crash course in remedial reading” or “get out of the awards business altogether” [Leonard 1974]). If we look at this issue as ethnographers, however, it seems more coherent to posit a clash between two diverging reading cultures. The board members were perhaps passionate lovers of literature, but as people with day jobs who read fiction after work, they had different literary sensibilities—more attuned, perhaps, to Gore Vidal’s bestselling Burr (which the jury had ranked third, after Pynchon and John Cheever’s The World of Apples). In all likelihood they were invested in the prize system’s promise of serious or “higher” entertainment (as opposed to “mere” entertainment as pleasurably killing time) but for a number of reasons, including training-specific rhythms of perception and generational tastes, they did not resonate with the maximalist fabulism on display in Pynchon’s novel. By contrast, the jury members were steeped in what John Guillory has called the “culture of the school”, with closer ties to scholarly networks and academically housed avant-gardes. They were thus more at home with what then emerged as the experimental cutting edge.

Varieties of Values (Strong/Weak, Sacred/Toxic/Everyday)

While ethnographers can live with the view that Gravity’s Rainbow is both “great” and “turgid”—depending on reception networks—, readers and critics find lived relativism acceptable only in proportion to their disinvestment (their sense that choosing between Vidal and Pynchon is not that important to their lives). Such disinvestment shapes a specific readerly mode, which Charles Taylor (1985) describes as “weak evaluation”. In moments of weak evaluation, we resemble purpose-rational consumers pursuing short-term desires in relatively private spaces. Here, the choice between Vidal and Pynchon becomes a bit like negotiating a plate of pastry: you might adore sponge cake in the morning, despise apple crumble at night, yet have no difficulties in tolerating others with different tastes—pastry habits rarely rope us into culture wars.

Weak evaluation is a common enough practice of everyday reading—on the beach we want whatever suits our situational now (could be Pynchon, could be a TikTok feed). Universalizing weak-value attachments has encouraged the misconception that, literature being mostly about pleasure, pleasure depending mostly on your palate, and there being no arguing about taste, artistic value is an inherently soft target. Such assumptions have bolstered cultural-studies intuitions about the fundamental pointlessness of canons or prizes and an ideology-critical centering of politics as the artwork’s supposedly more tangible core.

However, in moods of “strong valuation” literature can invoke a felt “higher pleasure” that strikes readers with a sense of contact with an identity-defining charismatic center. Whereas the pursuit of weak values is about what we already want, strong valuation follows from what we feel we should want after trusted institutions (artistic or civil-religious) rank our desires into higher and lower kinds. Indeed, the notion of “guilty pleasure” exists because as moral beings we can want to be told what it is good to want, not just to signal legitimized taste (the snob’s efforts of social distinction) but also to orient ourselves towards a greater good (the moral or civil-religious need to connect with collectively defined hypergoods).

Whereas weak-value moods keep Gravity’s Rainbow invisible unless we have an everyday use for it, strong valuation can make it rise above the everyday, even make it look down upon us as a sacred or a toxic thing (the former pulls us into worship, the latter into culture-warriordom).[2] Blood pressures rise, and the Pulitzer scandal can feel as polarizing to us as, say, the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision on Roe v. Wade. In this state of hypertension, Pynchon’s proponents decried the Pulitzer’s mediocrity (Gass 1985), while Vidal came to the board’s defense with a series of essays—“The Hacks of Academe” (1976) and “American Plastic” (1977)—that denounced postmodernism as a scholastic fad ruining the novel.

Critics, Scholar-Connoisseurs, Ethnographers

Within English departments it is common to wade into such debates as critics rather than ethnographers. According to Michel Chaouli’s superb definition, as a critic you ask whether a text “speaks” to you and compels you to “tell [others] about it” (Chaouli 2024, 3). Good criticism can thrive on self-analyses of how Gravity’s Rainbow’s affordances have moved you or left you cold. An ethnography of value, however, also needs to factor in how it affected other participants in the field (Murray 2025).

While this seems intuitive to field-working disciplines, as literature scholars we can feel that our accumulated experience and academic training gives our artistic sensibility an objective edge over other audiences. Michael Clune seems to make this claim when in A Defense of Judgment (2021) he obliges English professors to use their acquired taste to help students improve theirs. But how does my academic expertise give me an edge in anything other than, well, academic expertise? Field-defining skills are key to negotiating the field that defines them (as per Jonathan Kramnick’s Criticism and Truth [2023]). In the case of my own field—academic literary studies—, those skills would be classroom habits of reflexive close-reading, and scholarly benchmarks of multiple re-readability. But few, if any, non-professional audiences feel bound to such skills. The assumption that prestige can be justified or disproven by acute textual analysis seems useful only within collectives with relatively homogenous taste cultures.

An often overlooked source of heterogeneity even within a single taste culture is the socially embedded character of perception: placed within different relational ties, Pynchon’s affordances produce different affective atmospheres (sacred, banal, toxic, indifferent, liberating, constraining, and so on). Since these atmospheres are relational—they emerge only during lived immersion within a network of people and things—attempting to justify Gravity’s Rainbow’s prestige with reference to the text occludes how our own group-specific atmospheric immersion shapes what we experience as the text. In order to see value as an embedded social thing, we need to unlearn the widely shared intuition that true literary-artistic excellence and/or its ideological-political imbrications precede markets and institutions.

Relevance, Impact, Consecrated Consecrators

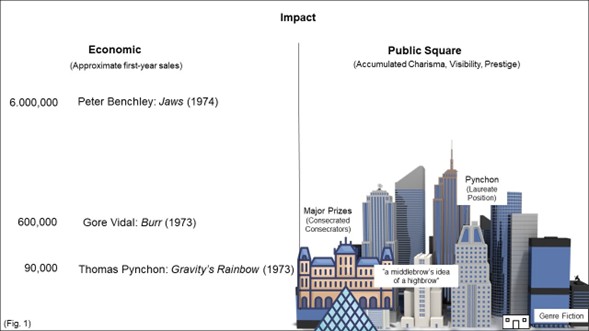

Ethnographies remain incomplete if they fail to trace the public relevance of values. While democratic societies contain multiple strong-valued horizons of higher pleasure, only few of these get to shape history books, classrooms, and museums. Curating institutions differ vastly in their “impact factor”, that is, their capability to shape what I call the public square, a spatially limited heritage-scape that materializes the literary field’s symbolic weights rather than its commercial or political assets.[3] Picture the public square as a cityscape whose buildings represent authorized prestige (see fig. 2). Here, the most iconic prizes inhabit the best real estate on the block while commercially more dominant institutions occupy more modest buildings (Danielle Steel and James Patterson sold more than one billion copies during their long writerly lives but are still nearly invisible in the public square).

Fig 2. Günter Leypoldt, “The Public Square”.

Whereas genre-fiction writers have a sense of their irrelevance on the public square (“I’d much rather sell books than get good reviews”, John Grisham recently told an interviewer, emphasizing how hard and liberating it was for him to learn over the years how to ignore literary authority [Liptak 2021]), the Pulitzer scandal was a conflict about who gets to inhabit literature’s strong-valued institutional center. And when the smoke of the heritage-making battles settled during the 1980s, Pynchon had become canonical while Vidal had been relegated, in Michael Lind’s description, to “a middlebrow’s idea of a highbrow” (Lind 2016). The reason that the Pulitzer board’s position now seems more “mid-cult” than it did in 1974 is that academic networks have further increased their impact on the public square.

To speak of “impact” is to use a term from scientific peer review that measures a journal’s capability to make a difference in its field. Peer-reviewed journals are curating systems that in theory should remain neutral (insulated from the higher or lower value of the research previously published in them), but that in practice become infected by the esteem that accumulates with selection histories and institutional affiliations (it would take years of bad editorial decisions to ruin the authority of Nature). A similar alchemy of contact charisma, I argue, pertains to cultural institutions: prestige awards like the Nobel, the Booker, or the Goncourt once began their social lives as ordinary curating institutions that over time morphed into “consecrated consecrators” (Casanova 2010, 300)—so enriched by their high-cultural affiliations over the years that they acquired a nearly civil-religious weight.

A common-sense response is to dismiss prestige prizes as establishment smokescreens that a minimal dose of readerly self-reliance will brush away. There is also ideology critique’s secularist habit of dismissing consecrated atmospheres as mere fantasy or fetishism that a more rational view of things should dispel. Yet the idea that readers or critics make informed strong-value decisions outside institutional trust relations, entirely on their own terms—mechanically sampling the texts that are “out there” to separate excellence from trash—is unrealistic not just because of the sheer volume of artifacts (120,000 new novels were published in the US in 2015 alone [English 2016]) but because as moral beings invested in “higher” entertainment we require orientation through collectively produced trust. Such orientation is mediated through institutions: stabilized social ties that connect people, things, and practices in hierarchical relationships. That these relationships are socially produced does not invalidate their relevance to how we experience strong and weak values.

The most tangible manifestation of impact is the well-known award effect: when a prestige prize propels a novel that no one expected to sell more than a few thousand copies into large-scale bestsellerdom. The award effect applies when atmospheres of consecration pull audiences towards aspirational reading, encouraging them to take on books they normally find too demanding or insufficiently entertaining but now approach as providing privileged access to a perceived higher cultural life of the nation. The career of Gravity’s Rainbow is a good case in point. Viking Press worried during production about how to recover the high costs for a difficult 700-page hardcover (Howard 2005), but their intense prepublication marketing campaign, in combination with immediate establishment rave reviews, produced so much Great-American-Novel buzz that a wave of orders lifted Gravity’s Rainbow briefly into the New York Times bestseller list. One year later the additional buzz of the NBA and Pulitzer nominations led Bantam to issue a mass market paperback. The Bantam edition looked like a cheap commodity, but centrally on its front cover it featured a pull quote in large letters as a stamp of consecration: “The most important work of fiction yet produced by any living writer” (see fig. 1).

All of this demonstrates the path dependency—hence relative autonomy—of literary consecration. Prestige effects can turn the most experimental works into aspirational bestsellers (think of García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, or Morrison’s Beloved), but commercial success as such yields no prestige. By the same logic, the more consecrated curators will sell more books (the Nobel even turns poets into bestsellers), but high sales have no consecration effects (as we can gather from the low heritage-making impact of genre-fiction prizes, Goodreads, or Oprah Winfrey). Although the term “bestseller” is often colloquially used to suggest cultural importance, numbers alone tell us nothing about impact: Gravity’s Rainbow sold about 90,000 copies in the first year, with the Bantam paperback reaching an estimated 250,000 over the next ten years (Howard 2005), astonishing figures for an experimental doorstopper. But they are well below Vidal’s Burr (which reached the higher six figures in its first year [Kihss 1974]), not to speak of mass-market blockbuster territory (Peter Benchley’s Jaws sold nearly six million copies in the year before the movie release in June 1975 [“Summer” 1975]).

That institutional authority cannot simply be bought, and sometimes withers through commercialization, is a lesson the Association of American Publishers learned the hard way after relaunching the NBAs as the American Book Awards in 1979. Remodeling them along the lines of the Oscars or Emmys, they added commercial categories, involved booksellers in the selection process, and produced a glamorous TV presentation. The decision-makers soon backpedaled when it transpired that the more commercial platform had not only failed to improve book sales (as prizes make little difference to mass-market blockbuster regimes) but also drained the NBAs of the institutional charisma that had just lifted the Booker Prize in England (McDowell 1983).

Conclusion: How Money and Singularity Reach a Good Match

The Pulitzer scandal shows how more commercial and more market-sheltered regimes of judgment can overlap and disaggregate. Of course, the Pulitzer board members were not just leisure readers but also representatives of a business model that between the mid-nineteenth-century industrialization of print and the more recent conglomeration of publishing has sought to stabilize profit margins by risk-reducing rationalization (Sinykin 2023). And the Pulitzer jury participated in this business model by contributing to the kind of reputational branding that remains important even to conglomerate portfolios (Thompson 2012). Yet the jury also represented a peer-review culture whose regimes of judgment significantly diverge from corporate rationales.

While since the 1950s, the rising conglomerate behemoths have raised the volume of a blockbuster-oriented entertainment industry, literature’s more recent academic patronage systems have provided experimental writers and prize juries with stronger market shelters. Contra neo-Frankfurt-school declension stories (closing minds in conglomerate-driven fetishscapes), the rising commercial turnover in the 1960s and 1970s helped to decouple the value judgments of prestige-prize juries and blockbuster curators in historically new ways. These developments are not reducible to straightforward ideologies because they involved figurational changes to literary culture, including the extension of tertiary education that between 1960 and 1975 produced larger college-educated audiences and more stable subsidies for experimental and avant-garde ecologies (McGurl 2009). These figurational changes are ill-explained by single binaries (Pynchon vs. the conservative mind) or large political-economy frames (cold-war liberalism, late capitalism, et cetera).

From a historical wide angle, the Pulitzer scandal was an iteration of an older conflict—beginning with the eighteenth-century print-market revolution—over how commercial appeal and literary singularity can be brought into a “good match” (Zelizer, 2011). Since money is always involved in cultural production, sustaining good matches requires ongoing boundary work, shielding the literary from self-enclosed ivory-towerism on the one side, and from pandering compromise on the other. As authority over such boundary work has shifted further towards expert curation, aspirational leisure readers occupy a more ambivalent position towards the institutional center. They largely finance the award effect, yet their limited agency within the high-impact prestige economies that dominate the public square means that their sense of strong value is reflected back to them as slightly askew—belated, too easily won, pandering, or simply “middlebrow”. But good or bad matches depend on standpoints unequally represented in social space. While it is relatively easy to determine a literary work’s economic value (measurable in sales), its literary worth requires more laborious ethnography. As a critic, I can know whether or not Pynchon speaks to me, and hope to persuade others about my own sense of a good match. But how can I know Pynchon’s actual life as a strong-valued object before I have studied the public square, as a relational space whose scales emerge from differing collectives that themselves differ in their performative impact?

References

Casanova, Pascale. 2010. “Consecration and Accumulation of Literary Capital: Translation as Unequal Exchange”. Critical Readings in Translation Studies, edited by Mona Baker, pp. 285–303. London: Routledge.

Chaouli, Michel. 2024. Something Speaks to Me: Where Criticism Begins. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Clune, Michael. 2021. A Defense of Judgement. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

English, James F. 2016. “Prestige, Pleasure, and the Data of Cultural Preference: ‘Quality Signals’ in the Age of Superabundance”. Western Humanities Review 70, no. 3: 119–39.

Gass, William. 1985. “Prizes, Surprises and Consolation Prizes”. New York Times, May 5. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/05/05/books/prizes-surprises-and-consolation-prizes.html.

Howard, Gerald. 2005. “Pynchon from A to V”. Book Forum 12: 29–40.

Kihss, Peter. 1974. “Pulitzer Jurors Dismayed on Pynchon”. New York Times, May 8: 38.

Kramnick, Jonathan. 2023. Criticism and Truth: On Method in Literary Studies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Leonard. John. 1974. “Pulitzer People Are No Prize”. New York Times, May 19: 421.

Lask, Thomas. 1979. “Book Ends”. New York Times, March 4: 12.

Leypoldt, Günter. 2025. Literature’s Social Lives: A Socio-Institutional History of Literary Value. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lind, Michael. 2016. “The Empire of Gore Vidal: The Legacy of an American Writer”. The Smart Set, Jan. 29. https://www.thesmartset.com/the-empire-of-gore-vidal/.

Liptak, Adam. 2021. “John Grisham on Judges, Innocence and the Judgments He Ignores”. New York Times, October 17. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/17/books/john-grisham-judges-list.html.

Locke, Richard. 1973. “One of the Longest, Most Difficult, Most Ambitious Novels in Years”. New York Times, March 11. https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/97/05/18/reviews/pynchon-rainbow.html?_r=2

McDowell, Edwin. 1983. “Publishing: New Life for American Book Awards”. New York Times, November 4: C28.

McGurl, Mark. 2009. The Program Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Murray, Simone. 2025. The Digital Future of English: Literary Media Studies. New York: Oxford University Press.

Raymont, Henry. 1971. “Judges of Book Awards Revolt on Use of Nationwide Polling”. New York Times, January 26: 22.

Sinykin, Dan. 2023. Big Fiction: How Conglomeration Changed the Publishing Industry and American Literature. New York: Columbia University Press.

“Summer of the Shark”. 1975. Time Magazine, June 23. https://time.com/archive/6846922/summer-of-the-shark/.

Taylor, Charles. 1985. Human Agency and Language: Philosophical Papers I. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Thompson, John. 2012 Merchants of Culture: The Publishing Business in the Twenty-First Century. 2nd Edition. London: Plume.

Zelizer, Viviana. 2011. Economic Lives: How Culture Shapes the Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

[1] For a more comprehensive account, see Leypoldt 2025. I am grateful to boundary 2’s anonymous reviewer and the issue editors, as well as to the organizers and participants of the Erlangen and UC Dublin conferences in June 2025, where I had the pleasure of sharing and discussing earlier versions of this essay.

[2] I use the semantics of the sacred in the spirit of Durkheim and Weber, denoting not religious belief but a practical sense of something larger about which one may have beliefs. Like strong values, the sacred is collective (transcending private purpose-rationalities), identity-defining (raising public monuments and calls for political action), and defined against two outsides: first, the sphere of the everyday, which neutralizes consecrated values (as when texts falling out of the canon become invisible); and second, the profaned or polluted pole of a consecrated hierarchy, which gives consecrated values a toxic presence that riles people into defensive action (think of the recent controversies over Cecil Rhodes, Peter Handke, or Woody Allen). For a more in-depth discussion, see Leypoldt 2025, 277–78.

[3] Note that my use of “public square”—as a metaphor for the limited space of material heritage-making in which plural prestige economies compete for public resources and authority—diverges from more familiar notions of the “naked public square” (as in Rawlsian debates on whether private morality and religion are to be kept out of procedural law) or the Habermasian public sphere.