Photograph by the author.

This article is part of the b2o: an online journal special issue “The Question of Literary Value”, edited by Alexander Dunst and Pieter Vermeulen.

Literary Value Emerges In and Against the Story Economy

Maria Mäkelä[1]

One of the global star authors of the 2020s, Édouard Louis, describes an emergent new literary aesthetic in an interview with the Los Angeles Review of Books in 2024:

the implicit doesn’t have a monopoly on beauty … There is a kind of revolution happening from certain points of the literary field, and I believe that interviews are a part of that, part of a possibility to say things without hiding. (Bell 2024)

By celebrating the freedom “to say things without hiding” Louis captures a shift in literary valuation that in the 2020s feels generational and converges with recent post-critical movements in literary theory. Students who primarily value authenticity and relatability in literature and look for authors who share these same values are taught by professors who continue to be steeped in a long twentieth century of literary theory and criticism founded on ideas of literariness and expert interpretations of the implicit, the paradoxical, and the difficult. For Louis, the “revolution” not only abolishes the tyranny of the implicit but also dissolves the generic and platform boundaries between the literary and the non-literary, as well as between text and paratext. In his vision, literary texts function alongside other types, genres, and platforms of storytelling, pursuing a shared rhetorical—and political—goal.

As an upwardly mobile author and a Bourdieu scholar, Louis is intimately acquainted with questions of literary value. His most ambitious autobiographical work Changer: méthode (2021) reads like a full endorsement of Bourdieu’s theories of literature as symbolic capital and its convertibility into other forms of capital:

I want to be clear: for me the key thing was change and liberation, not books or writing. I don’t think my primary obsession was with books. … What I’m writing shouldn’t be seen as the story of the birth of a writer but as the birth of freedom. (2025, 141)

By underscoring that his escape from poverty, violence, discrimination, and ignorance— conditions he endured as a homosexual growing up in proletarian Hallencourt in Northern France—could have taken any form other than a literary career, Louis stages a performance in which he trades literature’s symbolic capital for the urgency of class struggle and personal liberation. Again, as with the proclaimed aesthetics of the explicit, literature appears as interchangeable with or convertible into something else: it’s a tool or a means among many others. Morgane Cadieu (2024, 2) argues that “parvenue” authors like Louis “need more than one format to contain their cross-class trajectories”. Additionally, I would suggest that the popularity of socioautobiographies like Louis’s is to some degree related to the fact that social media amalgamate the social and the literary.

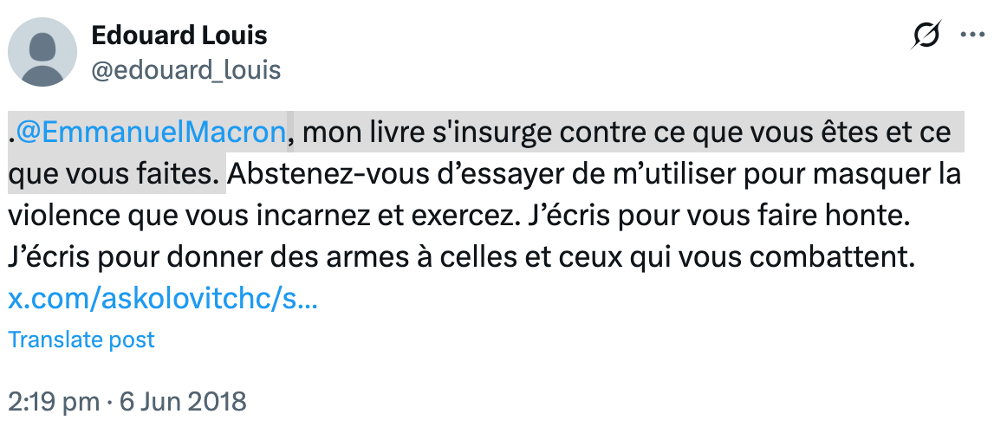

Louis is a prototypical author of the twenty-first-century story economy. He has successfully commodified a personal story of transformation, aligning with the imperative for authors to embody a consistent, shareable, and scalable story franchise. He maintains the kind of consistent transmedial authorial ethos that is rewarded not only by audiences, but— more significantly—by platform affordances and algorithms. Indeed, the continuity of Louis’s ethos across platforms and genres—from his autobiographical oeuvre to interviews, political pamphlets, essays, and social media profiles—forms an integral part of his aesthetics of the explicit. Paratexts extend both his personal story and its sociological analysis beyond the novels—and vice versa. In the wake of the Gilets Jaunes protests, Louis has successfully intervened in state politics and challenged Emmanuel Macron through a strategic blend of autobiographical narrative and online storytelling (see Cadieu 2024, 62–63):

@EmmanuelMacron, my book rebels against everything you are and do. Do not try to use me to mask the violence you embody and exercise. I write to make you feel ashamed. I write to arm those who fight against you. (Louis on Twitter, 6 June 2018, my translation)

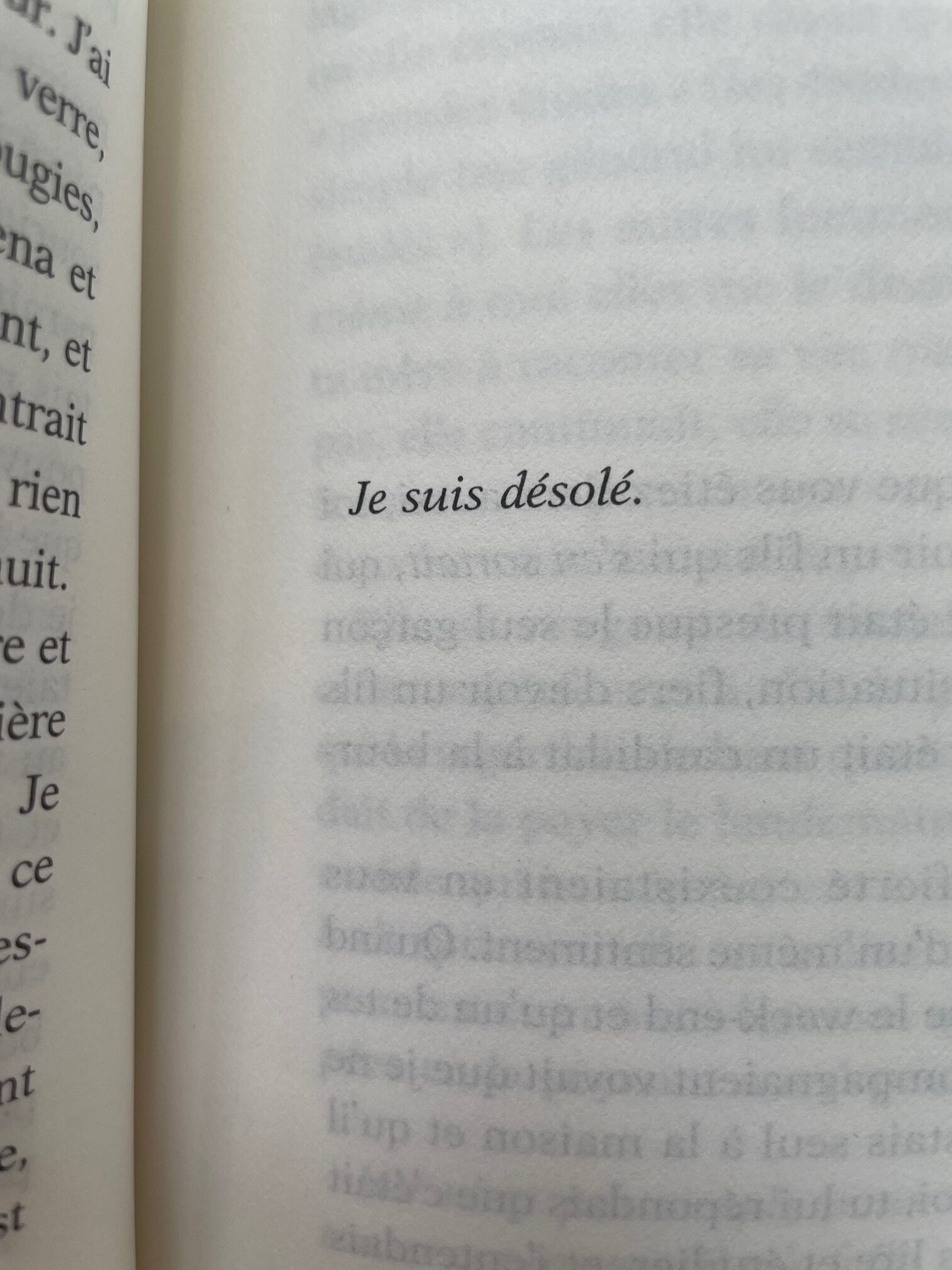

Moreover, in addition to the obsessive focus on the transformation of the self, it is also the repetitive, cyclical, and list-like visual and anecdotal poetics of his literary works that reflects platform value (apart from his participation in the tradition of experimental French autobiographical writing from Rousseau to Ernaux). Although Louis refrains from explicitly referencing social media storytelling, the structural and textual composition in his autobiographical novels evoke the aesthetics of digital platforms: highlighted captions reminiscent of Instagram stories, meme-like aphoristic wisdom, and a dialogicality akin to TikTok stitches or duets, where users juxtapose their argumentative videos with those of others. In Changer, one may find, for example, “Je suis désolé” (“I’m sorry”; 2021, 77; 2025, 55) spread across an otherwise empty page; or explicitness of intention and narrative positioning that verges on naiveté: “Je comprenais que Savoir = Pouvoir” (“I understood that Knowledge = Power”; 2021, 194; 2025, 151). Louis’s obsessive self-exposure and confessionalism does not unequivocally read as liberation but can also be considered – in the spirit of critical, symptomatic reading that predates the story economy – as a form of digitally induced self-surveillance.

While Louis may embody certain Foucauldian aspects of the story economy, he is simultaneously a shareable and scalable author whose compelling narrative conveys a clear, unambiguous sociopolitical stance—readily adaptable to a progressive discourse that thrives in digital spaces. From the perspective of modern or modernist ideals of ‘pure’ literature, the price to pay for relevance and visibility in the story economy is at least a partial loss of autonomy of the literary field as once defined by Bourdieu. Yet for a post-digital author like Louis, this loss marks a revolution, as for him, the boundaries between narrative genres and platforms, as well as the values they promote, have already collapsed.

***

Studies of literary valuation have not sufficiently dealt with the question of the digitalization and platformization of the literary field. Many crucial changes are introduced by the social media-fostered story economy that transform every user—from individuals to businesses and institutions—into storytellers. Research on the digital literary sphere (Murray 2018; Skains 2019; Thompson 2021; Pignagnoli 2023) focuses on the publishing industry, digital paratexts, the erosion of traditional institutions, the emergence of new literary platform elites, and parasocial relationships between authors and their audiences. Yet the effects of storytelling as a revenue model on the literary field and literary valuation remain insufficiently addressed.

Even less attention has been paid to how the platformized commodification of storytelling affects narrative rhetoric and literary form. I am not referring solely to the dominance of the autobiographical mode, to interactive writing practices, or to intermedial experimentations with digital interfaces within print literature, but to much deeper formal resonances between literature and digital platforms. Matti Kangaskoski (2021) names recognizability (manifesting as readability in literature) and a clear affective stance as platform norms that currently contribute to automated responses and a compression of both form and content in the literary field. To this should be added the most typically recognized affordances of social media, such as shareability, replicability, scalability, searchability, and persistence (see Ronzhyn et al. 2022).

The story economy has also prompted the “return” of the author, as the author figure functions now, perhaps more than ever, as a placeholder for intersectional or demographic representativeness and a “right to speak” (Busse 2013; Heynders 2023; see also Gibbons and King 2023, xix). The story economy commodifies personal narratives and capitalizes on experiences of trauma, transformation, and survival (Mäkelä et al. 2021). It elevates individuals’ lives and identities as exemplary and imposes an expectation of consistent ethos, habitus, and moral positioning sustained across media and platforms (Mäkelä et al. 2025). Authors may choose to ride the wave, fight against it, or turn away, but the overall platformization of the publishing industry and legacy media has made opting out very difficult. Today, the formation of literary value needs thus be understood in relation to the platform-driven imperative to produce and reproduce shareable, replicable, and scalable stories that are, moreover, capable of withstanding the critical scrutiny enabled by digital persistence and searchability.

The rise of new digital literary elites, such as BookTokers and GoodReads reviewers, and of the literary genres (such as romantasy) and values (such as relatability) they promote, drives many authors as well as legacy institutions to reinforce the prestige distinction of “Lit Fic” (Vermeulen 2023, 1232) more strongly than before. An author’s popularity on social media, or the affective, networked publics shaping a work’s or an author’s reception, or even the author persona’s ability to embody a particular narrative ethos may not feature explicitly in institutional “grammars of valuation” (1231). More likely, much of evaluative discourse by literary legacy institutions is implicitly positioned against the story economy, for example by celebrating such rarified genres as “nonautofictional metafiction” and complex entanglements of history, memory, and trauma (Vermeulen 1233), or authors who criticize or reject social media (Mäkelä et al. 2025; see also Gibbons and King 2023, xviii). Yet the difference between new digital elites and legacy arbiters may prove a generational rather than an institutional gap, as students in literary departments already represent a pragmatic, post-digital mindset, navigating digital environments where literary value is being “articulated and generated in concrete interactions” rather than stable and taken for granted (Vermeulen 2023, 1235). Therefore, studies on the grammars of literary valuation need to be able to account for platforms and algorithms, too.

The logic of digital storytelling platforms in literary as well as in any other context is completely reliant on what I call “emergent narrative authority”: while popular content is all about individual struggle and survival, no one storyteller can be held accountable for the rhetoric and ethics of the telling (Dawson and Mäkelä 2020). In the literary field, this means that the negotiation of authorial ethos is increasingly guided by algorithms and affordances that traditional literary institutions have no control over. Emergent narrative authority, as a concept, introduces a rhetorical perspective to what social media scholars study as context collapse (see Davis and Jurgenson 2014). In the literary field, contexts collapse and authorial ethos attributions are affected and complicated by platform affordances and values when, for example, citations are detached from novels and juxtaposed with social commentary by authors or audiences. In this context, we can surmise that the tendency in the contemporary literary field to foreground a strong, consistent, and pronouncedly embodied transmedial authorial ethos arises as a response or even as a defense against the emergent, distributed narrative authority of social media platforms and the narrative context collapse they induce. Édouard Louis as an embodiment of intergenerational trauma, structural violence, and literary prestige stands as an emblem of this simultaneously postdigital and reinforced authorship. Meanwhile, authors’ literary and non-literary gestures of rejecting social media can then be interpreted as attempts to evoke literary value as a counterforce to platformization.

Moreover, the algorithmization of the literary field risks eroding the distinction between discourses of valuation and instrumentalization. On social media, metrics—the number of shares, likes, comments, followers—form an integral part of both narrative rhetoric and its valuation (Georgakopouolou et al. 2020). Followers sharing an author’s inspirational story to engage in affective networks articulate their own identity through shared stories and thus accumulate their own narrative and digital capital. This surely suggests an instrumentalization of literature rather than a celebration of its autonomous value. Yet social media metrics currently constitute the most tangible and visible archive of collective literary valuations in the digital story economy. Quantifiable traces of valuation, from GoodReads reviews and their likes to social media shares of author interviews by the mainstream media, directly affect the public prestige of authors and their visibility.

***

While building his authorial ethos on ruthless authenticity and raw self-analysis, Louis nevertheless says nothing about his social media prominence in interviews nor in his autobiographical literary works. His fellow leftist intellectual star and frequent co-poster on Instagram, Geoffroy de Lagasnerie, asserts that “on Instagram, we seek to produce a different aesthetic of intellectuals: more real and more exciting” (qtd. in Menon 2023). What Louis does not reflect in his trans-platform narrative practice is the value of confessionality in social media and in literature. A ruthless analysis might suggest that in an economy driven by visibility, upward mobility is far more likely to be achieved through social media than through literary distinction.

What ultimately makes Louis so successful is his ability to play a double game when it comes to narrative and digital capital (see Ragnedda and Ruiu 2020) in the contemporary literary field (see Mäkelä et al. 2025). The storification of his split habitus (the fracture between his proletarian childhood and adolescence on the one hand and the identity of a world author celebrated by both the literary elite and online audiences on the other) requires emphasizing the autonomy and value of the traditional literary and intellectual establishments that he is able to conquer and challenge with his aesthetics of the explicit. Yet the tyranny of the explicit in literature, as I have argued, today inevitably means compatibility with platform affordances and values. Louis thus exemplifies the convergence of literary and platform elites, signaling a transformation in literary valuation and a corresponding decline in the autonomy of the literary field in the twenty-first century.

References

Bell, Stephen Patrick. 2024. “A Wound Is Objective: A Conversation with Édouard Louis”. Los Angeles Review of Books, 3 March. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/a-wound-is-objective-a-conversation-with-edouard-louis/.

Busse, Kristina. 2013. “The Return of the Author: Ethos and Identity Politics”. A Companion to Media Authorship, edited by Jonathan Gray and Derek Johnson, 48–68. Chichester: Wiley.

Cadieu, Morgane. 2024. On Both Sides of the Tracks: Social Mobility in Contemporary French Literature. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Davis, Jenny L., and Jurgenson, Nathan. 2014. “Context Collapse: Theorizing Context Collusions and Collisions”. Information, Communication and Society 17, no. 4: 476–85.

Dawson, Paul, and Mäkelä, Maria. 2020. “The Story Logic of Social Media: Co-Construction and Emergent Narrative Authority”. Style 54, no. 1: 21–35.

Georgakopoulou, Alexandra, Stefan Iversen, and Carsten Stage. 2020. Quantified Storytelling: A Narrative Analysis of Metrics on Social Media. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gibbons, Alison, and Elizabeth King. 2023. “Introduction: Authorship in Literary Criticism and Narrative Theory”. Reading the Contemporary Author: Narrative, Fictionality, Authority, edited by Alison Gibbons and Elizabeth King, xiii–xxxiv. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Heynders, Odile. 2023. “The Public Intellectual on Stage: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie”. Reading the Contemporary Author: Narrative, Fictionality, Authority, edited by Alison Gibbons and Elizabeth King, 3–22. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Kangaskoski, Matti. 2021. “The Logic of Selection and Poetics of Cultural Interfaces:

A Literature of Full Automation?” The Ethos of Digital Environments: Technology, Literary Theory and Philosophy, edited by Susanna Lindberg and Hanna-Riikka Roine, 77–97. London: Routledge.

Korthals Altes, Liesbeth. 2014. Ethos and Narrative Interpretation: The Negotiation of Values in Fiction. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Louis, Édouard. 2021. Changer: méthode. Paris: Seuil.

Louis, Édouard. 2025. Change: A Method. Translated by John Lambert. London: Vintage.

Mäkelä, Maria, Samuli Björninen, Laura Karttunen, Matias Nurminen, Juha Raipola, and Tytti Rantanen. 2021. “Dangers of Narrative: A Critical Approach to Narratives of Personal Experience in Contemporary Story Economy”. Narrative 28, no. 2: 139–59.

Mäkelä, Maria, Kristina Malmio, Laura Piippo, Matti Kangaskoski, and Markku Lehtimäki. 2025. “Social Media and the Value of Literature: Accumulating Narrative and Digital Capital in the Case of Johanna Frid’s Nora eller Brinn Oslo Brinn”. Tidskrift för Litteraturvetenskap 55, no. 1–2: 227–47.

Menon, Tara. 2023. “Parents and Sons: Édouard Louis’s Chronicles of Class”. The Nation, February 20. https://www.thenation.com/article/society/edouard-louis-class-politics/.

Murray, Simone. 2018. The Digital Literary Sphere: Reading, Writing and Selling Books in the Digital Age. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Pignagnoli, Virginia. 2023. Post-Postmodernist Fiction and the Rise of Digital Epitexts. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

Ragnedda, Massimo, and Maria Laura Ruiu. 2020. Digital Capital: A Bourdieusian Perspective on the Digital Divide. Bingley: Emerald.

Ronzhyn, Alexander, Ana Sofia Cardenal, and Albert Batlle Rubio. 2022. “Defining Affordances in Social Media Research: A Literature Review”. New Media & Society 25, no. 11: 3165–88.

Skains, R. Lyle. 2019. Digital Authorship: Publishing in the Attention Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thompson, John B. 2021. Book Wars: The Digital Revolution in Publishing. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Vermeulen, Pieter. 2023. “Reading for Value: Trust, Metafiction, and the Grammar of Literary Valuation”. PMLA 138, no. 5: 1231–36.

[1] This essay was written in the context of the consortium project Authors of the Story Economy: Narrative and Digital Capital in the 21st-Century Literary Field (consortium PI Maria Mäkelä, Research Council of Finland 2024–2028, decision 360931).