This text is published as part of a special b2o issue titled “Critique as Care”, edited by Norberto Gomez, Frankie Mastrangelo, Jonathan Nichols, and Paul Robertson, and published in honor of our b2o and b2 colleague and friend, the late David Golumbia.

Southern Circuits

Henry Neim Osman

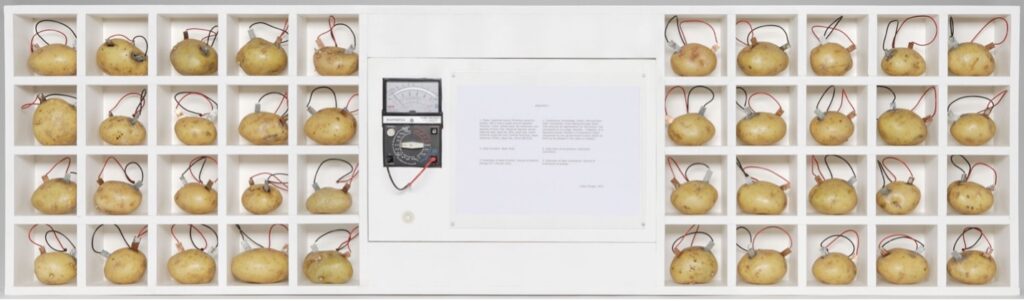

Victor Grippo, Analogía I, 1971, electric circuits, electric meter and switch, potatoes, ink, paper, paint and wood

Victor Grippo, Analogía I (2da. Version), Potatoes, zinc and copper electrodes, voltmeter, electrical cable and nylon monofilament, chair, wood, cloth, and text panel

Buenos Aires, 1970: Victor Grippo exhibits Analogía I. Forty potatoes are installed on the wall, their yellow-brown bulbous shapes inserted into a white grid. Each potato is placed in its own cell and connected to by two wires, red and black. In the middle, splitting the potatoes into two groups of twenty, is a voltmeter that measures the collective electric generation of this ensemble and a short text that elaborates the titular analogy in Argentine conceptual artist Victor Grippo’s Analogía I (1970/1) between the potatoes stored energy, connected by a grid of wires, and the burgeoning social conscience of a networked society.

Sao Paulo, 1977: Grippo remakes Analogía I. The voltmeter, text, and potatoes remain but the modernist grid has been disappeared as the potatoes are placed on a long banquet table. Strewn across a white tablecloth, with their wires tangled above, the clean lines of the first iteration have disappeared. Yet the analogy remains, transformed by the shift from the formal elements of the grid to the implied formlessness of the sheer mass of potatoes, from an organized matrix to a set of forms closer to how the potato itself might grow in the ground, as the set of potatoes behind the empty chair demonstrate. In the space between the grid and the tangle, between the modernist and organic networks, lies the politics of Grippo’s analogy.

Analogy comes from the Greek analogos, or proportion, meaning that it is the relation between two things unmediated by numeric counting. Analogy, and the analog, is not ontology, Kaja Silverman tells (or warns) us, but rather a similarity with a difference (2015). This essay takes up Grippo’s titular Analogía I as diagram, machine, and networked system, by attending to the synchronic difference of analogy and the diachronic difference of Grippo’s first and second versions. The first difference concerns the grounds for this analogy itself, in which biological and technical systems are analogized to the social. How was a political problem able to be understood as analogous to both interconnected vegetation and to the technical approximation of natural networks? In the same historical moment in which Grippo made his Analogías, and in response to similar concerns about how to, and whether one could, compare natural, technical, and social systems, Chilean biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela posited autopoiesis, or biología del conocer, as the theory of life’s self-production. Autopoiesis was always more than a theory of life, having distinct political and social dimensions both for Maturana and Varela, who disagreed on the organicism and holism underlying the theory’s political application, and the uptake of autopoiesis in varied realms, from Nikolas Luhmann’s legal theories to Sylvia Wynter’s theory of the overrepresentation of Man. Analogía I offers a parallel trajectory, one in which social, organic, and inorganic systems are circuited together and stages the same tension that lead Maturana and Varela to disagree on the possibility of a political autopoiesis.

If the first difference concerns analogy as a structural principle, and the theoretical grounds for Grippo’s analogy, the second difference takes up the precise meaning of the historical shift in the formal elements of Analogía I. At first glance, much has changed. The grid, with its clean lines and roots as a technology of organization and territorialization, would seem to be opposed to the interwoven wires and roots of a natural form. Does not a grid overlay and overwrite the contingencies of life? Does not there seem to be a startling difference between the cell-like grid and promise of a different, and perhaps more natural, mode of social organization in the second version of Analogía I, in which the potatoes are strewn across a communal table? At first glance the grid appears to be a technology that captures while the second version would be one that frees, bringing forward the tensions inherent in a work that claims to model, slightly tongue in cheek due to its elementary-school experiment, how a computer could model social conscience. It also restages centuries old debates between mechanism and vitalism. Yet the table, chairs, and plot of soil in the second installation maintain the sharp angles and rectilinear forms of the grid. These two iterations are less distinct than they appear, reducing the severity of the formal shift and the seeming antagonism between the two different network topologies. Rather than a crisis of meaning, in which the work calls forth a certain indeterminacy to the politics of the network form because of interchangeable topologies, what is left is a subtle critique of demands to model the interdependence of the social field and its web of mutual interdependence or care, located here in roots and wires, by overdetermining its relationship to natural and technical systems. The shift in the formal elements of the network here offers a path away from a holism of the network that emerges from the historical conditions of the Southern Cone in the 1970s, like autopoiesis, by allowing the social field to determine itself as an open site of contradiction.

II

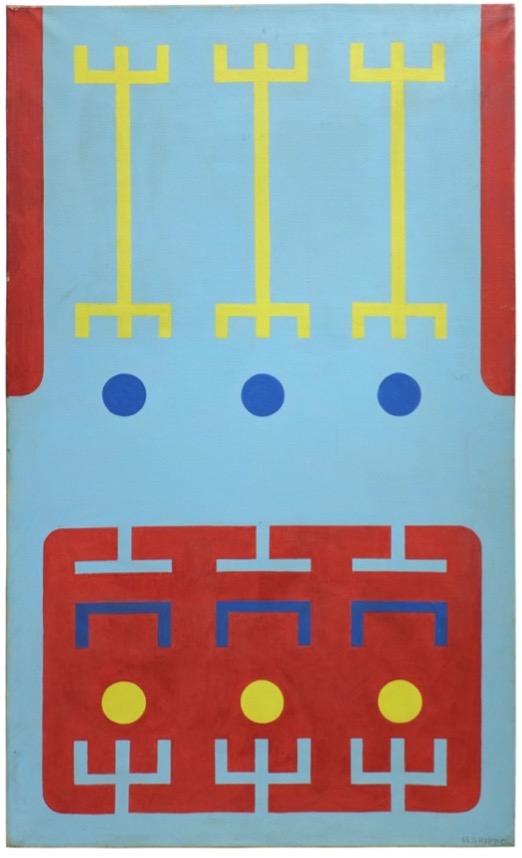

Grippo, Sin titulo, 1966, oil and graphite on linen

In 1966, Grippo began his investigation of energy and the circuit in a series of abstract paintings of geometric elements. In a work from this year, a simplified set of forms are rendered in primary colors of contrasting red, blue, and yellow, which transform the visual language of technical documents into a set of iconic relations. Here, abstraction is what enables analogy: stripped of their specificity, these works invoke everything from silicon chips to abstract textiles to concrete and constructivist art. The clean lines preface the machinic nature of Grippo’s later works, yet the individual icons are disarticulated from a larger circuit. Silicon chips have oft been compared to a range of visual forms. Media historian Lisa Nakamura, writing on the early production of silicon chips by Fairchild Semiconductor by Navajo women, notes how in 1969 Fairchild, in its own publicity material, would parallel the abstract design of Navajo woven rugs with the design of silicon chips. Placing images of rugs and chips next to each other to draw forth their shared formal elements, Nakamura underscores how the “resemblance between the pattern of the rug depicted on the first page and the circuit is striking and uncanny. It makes the visual argument that Indian rugs are merely a different material iteration of the same pattern or aesthetic tradition found within the integrated circuit,” (2014, 926). Computer scientist Bernhard Korte compares early integrated chip designs from the 1960s to the 1980s to works by Wassily Kandinsky and Josef Albers, because “the structures inherent in chip design and chip reality are, after all, nothing but simple geometric forms,” (1991, 63).

While Grippo’s circuit paintings make a parallel movement in the same historical moment, abstracting the set of shared simple geometric forms between chip design and abstract art, these paintings also recall the development of arte concréta or concrete art in Argentina. Concrete art as a term was first coined in 1930 by Theo van Doesburg and was widely embraced in Argentina and Brazil by artists like Lidy Prati in the 1950s. Deeply mathematical, concrete art was non-representational, meaning that geometric forms – point, line, and shape – referred to nothing more than themselves as representations of pure rationality. As a 1946 manifesto by the Argentine Association of Concrete Art contends, “A scientific aesthetics will replace the millenary, speculative and idealistic aesthetics” and “Concrete Art familiarizes man with a direct relationship with things, not with the fiction of things,” (Inventionist Manifesto, 1946, 8). Grippo’s later work pushes back against the anti-idealism of concrete art, and even the early paintings seen above pair the visual language of concrete art with a set of forms that recall a range of natural and technical systems. The open two and three pronged shapes, separated by small dots, recall the abstracted elements of a computer circuit and “were figurative… I went on to use abstraction and from there a certain symbolism,” (Grippo, 2004, 319). In bringing what he termed mechanical models into conversation with concrete art, these paintings bridged concrete art’s anti-idealism with a certain symbolism. In an interview, he described this process as moving from “painting them [mechanical forms] (like a step in a process of evolution) to incorporating them into a system of symbols, a language,” (Grippo, 2004, 321). The structuralist influence here presages how the later network in Analogía I is a one defined by the (negative) relations between its constituent parts.

In the following year, Jorge Glusberg, an Argentine artist and curator, founded Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAyC), of which Grippo was a part. CAyC’s first exhibition was Arte Sistema which brought together the cybernetic systems thinking that was already circulating in European and American art practices with an inherent social critique from the South.[1] Glusberg framed these interventions as an ideological conceptualism, a phrase borrowed from Spanish critic Simon Marchan Fiz (Zanna, 2009). This was a refashioning of conceptualism as a distinctly political project tied to third-worldism and anti-psychiatry. Glusberg deployed this term to distinguish CAyC’s projects, and later exhibitions and interventions organized by Glusberg as Grupo de los Trece, from Western conceptualism, which he argued failed to respond to the political and material specificities that CAyC and Grupo de los Trece faced. This echoes what Luis Camnitzer calls the “regional clock,” which distinguishes the distinct temporality of regional conceptualisms (of which Europe is one as well) to critique universal periodizations (Camnitzer 2007, 28). At the same time, this was not a group of works united by a singular ideology nor by a unified mode of critique. Rather, they were organized by their opposition to the dominant ideologies, both artistic and social, in contemporary Argentina via a wide range of dematerialized practices (Glusberg, 1972).

In 1970, amidst these shifts in Argentine art production, Grippo’s practice turned from circuit paintings to large scale installations, often using the potato, that grappled with social issues. Grippo writes that he:

[B]egan to work with potatoes as a material… ‘to consecrate’ an everyday object and discover its multiple significations. Art and science—logic and analogue—served as instruments. Later, almost without thinking about it, I articulated some symbols: man’s foodstuffs, the trades, energy and the rose, the disequilibria and consequent transformations. (Grippo 2014, 16)

The potato is a central part of Grippo’s complex visual language, along with roses and lead, due to his ongoing interest in alchemy and the history of science and served as a connection to life and liveness, in particular. He also writes, in verse, that:

I consider myself a realist

what is more real than a live potato

what is more real than Pb (lead) carried [sic]

shown in its fixity, in its behavior,

what is more real than seeds (Grippo, 2014, 19).

Life, then, is as much the object of Grippo’s work as the circuit. Change over time, growth, the ability to open and change with the world, the living material of the potato symbolizes the possibility for both individual and social growth. He also, in a conversation remembered by critic Guy Brett, cited post-war British military experiments aimed at building biological batteries powered by micro-organisms as one influence,(Grippo 2017, 8). Analogía I, then, can be read as a more liberatory re-reading of this military project that sought to imagine a biological battery for social conscience instead of for military power.[2]

At the center of this re-reading, both theoretically and literally, was the voltmeter and related text at the center of the first version of Analogía I. In it, Grippo lays out three analogies: (1) between “Papa (Quechua name)” and the Latin concientia, “the inner feeling through which man acquires an appreciation for his actions… freedom of conscience. Right recognized by any government to each citizen to think as he pleases.”; (2) between the potato as “daily function; basic food” and “daily form of conscience; individual conscience,”’ and (3) “extension of daily function” source of electric energy (0.7 volt per unit) and “extension of conscience. Source of conscience of energy.” [3] The potato here becomes the locus of a set of entangled analogies to energy, freedom, rights, and conscience, both individual and social, but also how we become aware of our own actions and their impact on others, which is to say, it asks about networks of care on a macro level.

Each tuber’s .7 volts of latent power are wired together, measured by the central voltmeter as an analogy for the general power of the social field. In connecting each individual potato with wires, the rhizomatic root network of a potato plant is replaced with the technical assemblage of wire, electrode, voltmeter and potato. Put differently, a technical network replaces a natural one, materializing and systematizing the formal relations between different parts of a single organism. Unlike the cybernetic analogy, which placed organic and inorganic systems on the same field, allowing for a set of equivalences and exchanges between distinct systems, Analogía I refuses distinctions between the organic and the inorganic in favor of a different network analogy, in which the social field is always already natural and technical. There is no distinction to be overcome. A series of distinct phenomena are thus rendered parallel, as potato is equated to person, energy to cognition, and a burgeoning techno-organic network to social relations. Further, the voltmeter computes the total electrical generation produced by the system which, following Grippo’s own analogy, is a computation of a social conscience and consciousness.

It is precisely this question of the politics of the network that returns us to the grid. Analogía I forwards an ambiguous politics that vacillates between the potential of a coming-together referenced in the written analogies to the severity of the grid itself, a move that celebrates mutual care while also subtlety critiquing the political potential of this analogy through the grid that mediates the network. Justo Pastor Mellado notes that as much as Analogia I is about an emerging consciousness, the potatoes are enclosed in wooden cages (Mellado, 2004, 308). The cell of the grid echoes the plant cell, which at the moment of its discovery was named after the Latin cella, for a small room reminiscent of a monk’s cell (Mazzarello, 1999). The plant cell was then always emergent from an architecture of power meant to organize bodies, or in this case raw being. Multiple parallel cells, separate but together, produce the vitality of multicellular life just as different potatoes, distinct but linked together, produce consciousness for Grippo. We could term this cellularity, denoting the collapse of social and spatial relations with biological ones through the figure of the cell. Pastor Mellado also argues that just to mention an electrode “reminds us of torture; in particular, the application of an electric current to the body,” (2004, 308). A computer that models social conscience and consciousness becomes as menacing as it is liberatory, capturing life as much as it emancipates it.

Yet more than the torture chamber, the grid here denotes a tension between the organic and the inorganic and the twin processes of regularization and normalization. As Bernhard Siegert notes, the grid is a cultural technique of ordering and representation that is first an imaging technology, because it projects a three-dimensional world into a two-dimensional plane, secondly a diagram that traverses the real and the symbolic, and finally it constitutes a world of objects imagined by a subject in his reframing of the Heideggerian gestell (Siegert 2015, 98). Put differently, the grid is a medium that merges representation and operation through deixis. Yet a second idea of the grid for Siegert emerges in which it symbolizes a cartographic imaginary emergent from South America and Argentina in particular. Here, the grid is the organizing principle of colonial topography, a division and organization of space that, while originally devised in antiquity, reaches its advanced form in the Spanish colonial city plan, which is infinitely reproducible and expandible (2015, 108-9). It is in the city that the grid re-emerges in three dimensions, moving from abstract deixis and cartography to a principle for the ordering of space through reproducible cells, which are both organizational technique and visual practice. And it is in Argentina that Siegert locates the apogee of the grid as a spatial technique in three dimensions. In 1929, Le Corbusier visited Argentina, where he developed his theory of the cell as the building block in architecture, both via his trip in an ocean liner to Argentina and his plane rides over different cities in South America, like Buenos Aires, La Plata, and Montevideo, which had distinct grid plans. For Siegert, “Le Corbusier’s real model for cellular construction was neither plant nor prison but the machine,” an idea that he claims only developed in his visit to South America (2015, 116).

Is not neither plant nor prison but machine the central principle of Analogía I? As neither holist organic networked, linked by mutual exchange and care, nor model for the prison cell, Analogía I is a model of a social machine that is always-already organic and inorganic, holding the potential for new ways of coming together just as much as it holds the potential for capture and control, a contradiction that structures for Grippo’s installation and that he never seeks to paper over. Yet, the grid here takes on a distinct valence, as, contra Siegert, it is not a cultural technique of ordering and of territorialization, emerging from cartography and Renaissance perspective, but a network architecture.

III

This second formulation of the titular analogy is thus not a return to a prelapsarian before, bringing a social conscience back to the soil, which in this version is constrained to a single square behind the chair. Each potato remains networked and connected to a single point: a voltmeter, albeit one that instead of dividing the installation into two equal parts is set off to the side like a pulpit or control panel. There are three major changes here: the grid has been replaced by a non-standardized and distributed network; some potatoes have been returned to the soil without being disconnected; and an empty chair holds not the head of the table but serves as a step for yet more potatoes as they move from ground to a set table, or vice-versa.

Analogía I (2da. Version) rejects the grid as organizing principle but does not reject the central analogy of the installation nor Grippo’s material theorization of the social as an (in)organic machine. If the first iteration was organized into a set of discrete elements, here there is a return to more seemingly natural forms that recall less the prison cell than woven knots of roots in soil. Despite organizational differences, Grippo’s intervention remains the same, asking the viewer to analogize a deceptively simple system of potatoes and wires to a broader theory of the social. In both, it is the voltmeter that serves as the interface between system and environment. The formal shift in organization between the two installations, alongside the maintenance of the analogy itself, may seem to point to an incoherence to the political claims that ground his analogy. However, it is the refusal of easy organicist interpretations that would prioritize organic networks as a model of the social or mechanistic interpretations that would prioritize technical interconnection that grounds Grippo’s work. The fundamental contradiction between the two different version of Analogía at the level of the politics of their networked form, between each potato being held separately or strewn across a table such that they can touch each other, speaks to the tension between the network as a mode of control and a new horizontal modality of care, even as they both remain more similar than they appear.

In 1972, between the two versions of the installation, CAyC organized an exhibition in a public plaza. Grippo installed a rural-style oven to make bread, handing out warm bread in an installation that merged proto-relational art, arte povera, and his own interest in transforming simple materials through heat and energy. The next day, the police impounded the installation and destroyed the oven. The epigraph to the exhibition has included a long quote from Louis Althusser, that “One could propose the hypothesis that a great work of art is that which acts within an ideology at the same time that it distances itself from it to constitute an act of critique of the ideology it sets forth, in order to allude to different ways of perceiving, feeling, hearing, etc., that surpass existing ideology by freeing itself from its latent myths,” a line of critique that aptly applies to Analogía I as well (Longoni 2004, 285). Analogía I proposes new ways of interconnecting and raising the social conscience while also subtending such a possibility, forwarding an ideology critique of both the network and attempts to organize the social following nature’s own systems of interconnection, holding up care as critique and critique as care.

A parallel debate on the relation between nature and the social and the politics of the model was occurring across the Andes, where Chilean biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela De Maquines y Seres Vivos began outlining their theory of autopoiesis or la biología del conocer and eventually diverged due to Maturana’s belief that a social autopoiesis was possible, an organicist turn that Varela strongly disagreed with. Autopoiesis is a theory of self-organizing systems that grapples with the foundational question of what is (cellular) life, but it is a theory of politics and social organization as well.[4] Autopoiesis, in its beginnings, concerned how nervous system activity, and thus the organism in general, is only triggered by the nervous system itself, and the “external world would have only a triggering role in the release of the internally determined activity of the nervous system.” (Maturana and Varela, 1980, 121). It is in this observation that autopoiesis is borne, as the circular activity of the organism (or the cell, or the system) constitutes the auto-, the self-production at the heart of the theory. A central question is thus how can an organism maintain its own identity as it constantly changes.

Maturana and Varela distinguished between the organization of a unity (an inside, a system, an organism) and a medium (in which the unity is embedded), which can also be phrased as the difference between the system of relations that constitute a unity and the actual structure of a unity in a particular moment (Maturana, 1972, 46-47). Organization is maintained even as structures change. Further, the relation of unity to medium, or how the unity is embedded and relates to its environment, is a pre-requisite for life. In a late publication, Varela reframed the central tenets of autopoiesis as whether the system has a semi-permeable boundary, is self-producing, and able to regenerate the components of the system (Varela 2000). Key to these distinctions is semi-permeability and operational closure. The former is how autopoietic systems are organizationally closed but structurally open, while the latter refers to how autopoietic systems are neither representational, because the terms of the systems reactions are determined by its organization, nor solipsistic, because the nervous the system does interact with the environment at the level of its structure. Outside inputs are triggers that are only registered if the system’s organization allows them to be. The relatively simple recursivity of first order cybernetics’ theories of feedback is now transformed to one in which the observer is not a neutral transducer of information but actively produces itself.

Analogía I is not an autopoietic system per se, but the tension between an autopoietic theory of a system and Grippo’s installation reveal something of a nascent Southern circuit, emergent from the political and material conditions of the Southern Cone, organized around the same central contradiction as the two versions of his installation. The network modeled in both versions of Analogía I contains something of a cybernetic enclosure, as it is only accessible through the voltmeter that selectively determines and processes the systems output. What is crucial here is not the network itself, in autopoietic terms the structure, which is of course not self-reproducing as a potato cannot wire itself nor produce new mechanical components, but rather how Grippo analogizes two distinct autopoietic systems of the organic potato and the social, united by a technical apparatus. It is here that the political implications of autopoiesis can be drawn forth, even as autopoiesis is often understood as either an epistemological or ethical rather than political quandary by interlocutors in the humanities and social sciences. This is the crux of Cary Wolfe’s critique of how autopoiesis contains a humanism that:

manifests itself in the philosophical idealism which hopes that ethics may somehow do the work of politics. What we find here, in other words, is (to borrow Fredric Jameson’s formulation) a kind of “strategy of containment” whereby the post-humanist imperatives of second-order cybernetics are ideologically recontaied by an idealist faith in the social and political power of reason, reflection, voluntarism, and what Jameson calls “the taking of thought (1995, 62).

For Wolfe, this is due to Maturana and Varela’s transformation of the particular values of their milieu into a universal theory of the system, particularly their focus on the necessity of love, which is transformed into imperative. This leads to a confrontation with the fundamental idea for him that all points of view are not valid because they have differentially distributed effects in the social field. Where then is social antagonism?

If Wolfe seeks to uncover a latent humanism in autopoiesis, Sylvia Wynter turns to autopoiesis to understand, and subtend, the production of the liberal human throughout her work, starting with her 1984 essay “The Ceremony Must be Found.” For Wynter, whose wide-ranging oeuvre is too expansive so be summarized here, autopoiesis serves as the mechanism for her hypothesis of auto-speciation and elaborate a “new science,” in conjunction with Caribbean thought (Wynter 2003, 328). Autopoiesis serves as the logic behind how sociogenesis functions, in material-semiotic systems, and how certain genres of the human have become overrepresented, leading to a world in which Man2, or the liberal homo oeconomicus has come to stand in for the human.

Wynter, while primarily focusing on autopoiesis as a biological theory that she brings into conversation with Black and Caribbean philosophy, attends to autopoiesis in its larger dimension as theory of the social. Yet, the focus remains on neuro-biological feedback, particularly among her interlocutors. For Katherine McKittrick, Wynter:

[R]eads biological theory to claim that autopoiesis—the consensual circular (not teleological-evolutionary) organization of human life through which we scientifically live and die as a species—draws attention to “a new frame of meaning, not only of natural history, but also of a newly conceived cultural history specific to and unique to our species, because the history of those ‘forms of life’ gives expression to [a] . . . hybridly organic and . . . languaging existence, (2015, 145).

Such readings of autopoiesis render it a theory of the cell and remove its epistemological, and political, valences. Similarly, in the same volume, Walter Mignolo charts a divide between autopoiesis as theory of perception in which:

[T]he living organism that fabricates an image of the world through the internal/neurological processing of information. Thus, Maturana made the connection between the ways in which human beings construct their world and their criteria of truth and objectivity and noticed how their/our nervous system processes and responds to information. (2015, 106)

What is missing here is precisely how autopoiesis was never just a theory of perception, except perhaps in its earliest form as Maturana and Lettvin’s experiments on the frog’s eye 1959, over a decade before Maturana and Varela first deployed the term autopoiesis. In rendering autopoiesis a scientific theory transferred to the social field, the particularities of autopoiesis’s emergence remain obscured.

Autopoiesis was always-already a critique of reason, at least for Maturana if not for Varela. In their later years, the two diverged on precisely this question of politics. Maturana, in a 1991 letter responding to a review of the Tree of Knowledge, critiques “the defense of truth, the defense of reason, or the defense of universal transcendental values under the claim that the defender is intrinsically right and the others are intrinsically wrong,” (1991, 92). Here, Maturana is suspicious of both reason and truth and their claims to universality grounded in an enlightenment idealism, because he distinguishes between “constitutive operational legitimacy of all manners of living in the biological domain,” which “does not carry with it the acceptance of all manners of living as equally desirable in the human domain of coexistence,” a distinction that echoes the autopoietic division between organization and structure (Maturana, 1991, 92). Central is how Maturana can never know what is “biologically, transcendentally good” or “biologically transcendentally bad,” (1991, 90-91). Maturana is not speaking abstractly about reason or truth, however. He grounds his critique in Pinochet’s dictatorship, which he opposes on political grounds rather than by that he is intrinsically right. This is clearest in a response Maturana wrote to Morris Berman’s review of The Tree of Life. Berman claimed that Pinochet was, when read autopoietically, “biological distortion” and that Allende was “biologically legitimate,” leading Maturana to contend that “Berman says that he is not ‘willing to display any tolerance; to people like General Pinochet. If he says so because he thinks that he is intrinsically right and that General Pinochet is intrinsically wrong, he is speaking like General Pinochet,” and that “Salvador Allende does not “represent one of the highest forms of biological integrity,” as Berman says. He was a human being who could not escape being trapped in the meshes of a network of ideological fanaticism. There is nothing like a biological distortion or like biological integrity in the domain of biology,” (1991, 91, 96) In a strange turn of phrase here, Maturana both rejects claims to biological legitimacy through an understanding of biology. Even as nature cannot be used as the grounds for making a political claim, he still deploys autopoiesis as a framework for politics: there is no operational legitimacy in biology, but only autopoietic operations are legitimate.

For Maturana, then, autopoiesis is a political response to organicist claims that ground politics in biology, or biologize and naturalize the political field, while, at the same time, contending that the very rules of the social are still emergent from biology – he wants to have it both ways. He applies autopoietic semi-permeability or operational closure to the political realm to ground the autopoietic organization of politics in nature or in his words biology, while disavowing such moves at the level of structure. Varela strongly disagreed with Maturana’s turn to autopoiesis as a theory of the social field because:

[A]ll extension of biological models to the social level is to be avoided. I am absolutely against all extensions of autopoiesis, and also against the move to think society according to models of emergence, even though, in a certain sense, you’re not wrong in thinking things like that, but it is an extremely delicate passage. I refuse to apply autopoiesis to the social plane. That might surprise you, but I do so for political reasons. History has shown that biological holism is very interesting and has produced great things, but it has always had its dark side, a black side, each time it’s allowed. (Varela, 2002)

In rejecting the inherent organicism and holism of Maturana’s autopoiesis tout court, Varela underscores the failures of politics emergent from biology, a charge that Maturana himself tries to avoid by distinguishing between how all life has operational legitimacy and the non-acceptance of all these legitimate autopoietic unities as good. Following Wolfe’s critique, this is also the effect of a latent humanism in autopoiesis both in its development of universal rules and in its inherent speciesism. Autopoiesis seeks to escape organicism by the same mechanisms with which it defines its own semi-permeability to the world: operational closure.

There is an echo in Maturana and Varela’s debates over autopoiesis’s political valence and how it can serve as a critique of reason and truth, due to how it destabilizes any claim to a universal even as, via sleight-of-hand, it functions through a set of seemingly natural laws itself, of the tensions between the two instantiations of Analogía I. Turning to autopoiesis uncovers a shared concern with how social systems are modeled on, nested in, and emergent from natural systems following natural laws that emerged in tandem. Yet Grippo never offers a hierarchy of one system to another, in which the social field is immanent from and reducible to, at the right level of abstraction, the organization of a cell. Instead, he makes a parallel move, destabilizing the network as a technology of either capture and liberation, restaging Maturana and Varela’s debate. Beyond showcasing a crisis of meaning of the network in this era, there is also a nascent critique against reducing mutual interdependence to a technical or natural system and the easy analogies between environmental and natural networks that impoverish both. In thus critiquing overdetermined theories of the social field by acting within it (via the model), Analogía I makes the network and circuit visible. In the move between the grid and the entangled network, between the plant, the prison cell, and the machine, what structures the scene is a social and political field that remains open and able to serve as the grounds for politics. The social can never be fully resolved because the same analogy can be organized differently such that one iteration can be read as a torture chamber and another as a cell. If for Maturana “the social is constituted in relations of love,” (1991, 89) which are also relations of care, Grippo’s installation models a different yet related circuit in which antagonism, difference, and contingency, which is to say politics itself, remain open. Systems, and here the social, can be organized differently – that is the work, rather than ascertaining a certain truth in nature or technics. Instead of elevating biologically inspired notions of care and love, at the risk of holism or organicism, pace Varela’s critique, Grippo holds them in delicate tension: machine and vegetable, electricity and life, grid and tangle.

Henry Neim Osman is a PhD candidate in the Department of Modern Culture and Media at Brown University. He works across media theory, science and technology studies, and philosophy of technology. His dissertation, “Analog Immediacy: Computation and Critique at the Ends of the Digital,” historicizes the recent resurgence of analog computing and AI and critiques how life is reconceptualized by new computers at the limits of the digital. His work has been published in Digital War, Film Quarterly, Surveillance & Society, and Media Fields.

References

“ICAA Documents Project Working Papers Number 5.” Houston: Museum of Fine Arts Houston (MFAH), 2017.

“Manifiesto invencionista”. Accessible: https://monoskop.org/images/1/18/Manifiesto_invencionista_1946.pdf.

“Victor Grippo,” Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporaneo (MUAC), 2014, 16. Accessible: https://muac.unam.mx/assets/docs/p-057-f_muac_016-int-grippo.pdf.

Camnitzer, Luis. Conceptualism in Latin American Art: Didactics of liberation. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007.

Gilbert, Zanna. “Ideological Conceptualism and Latin America: Politics, Neoprimitivism and Consumption.” rebus: a journal of art history & theory 4 (2009): 1-15.

Glusberg, Jorge. “Arte e ideología,” Hacia un perfil del arte latinoamericano. Buenos Aires: Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAyC), 1972.

Korte, Bernhard. Mathematics, Reality, and Aesthetics – A Picture Set on VSLI-Chip-Design. Berlin: Springer Verlag, 1991.

Longoni, Ana. “Víctor Grippo: his poetry, his utopia.” In Grippo: Una Retrospectiva, ed. Marcelo Pacheca. Buenos Aires: Malba, 2004. 283-291.

Maturana, Humberto R. and Francisco J. Varela, Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living. Dordrecht: D. Reidel, 1980.

Maturana, Humberto R. “Response to Berman’s critique of the Tree of Knowledge.” Journal of Humanistic Psychology 31, no. 2 (1991): 88-97.

Maturana, Humberto R., and Francisco J. Varela. The tree of knowledge: The biological roots of human understanding. Boulder: New Science Library/Shambhala Publications, 1987.

Mazzarello, Paolo. “A unifying concept: the history of cell theory.” Natural Cell Biology 1, E13–E15 (1999).

McKittrick, Katherine. “Axis, bold as love: On Sylvia Wynter, Jimi Hendrix, and the promise of science.” Sylvia Wynter: On being human as praxis (2015): 142-63.

Mignolo, Walter. “Sylvia Wynter: What Does It Mean to Be Human?”. Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis, edited by Katherine McKittrick. New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2015, 106-123.

Nakamura, Lisa. “Indigenous circuits: Navajo women and the racialization of early electronic manufacture.” American Quarterly 66, no. 4 (2014): 919-941.

Pastor Mellado, Justo. “Víctor Grippo’s Chilean novel.” In Grippo: Una Retrospectiva, eds. Marcelo Pacheca. Buenos Aires: Malba, 2004. 307-311.

Siegert, Bernhard. Cultural techniques: Grids, filters, doors, and other articulations of the real. Fordham University Press, 2015.

Silverman, Kaja. The Miracle of Analogy, or, The History of Photography. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2015.

Van Doesburg, Theo. Concrete Art Manifesto. Accessible: https://monoskop.org/images/9/91/Concrete_Art_Manifesto_1930.pdf.

Varela, Francisco “Autopoïese et émergence.” In La Complexité, vertiges et promesses. Ed. Réda Benkirane. Paris: Le Pommier, 2002.

Wolfe, Cary. “In search of post-humanist theory: the second-order cybernetics of Maturana and Varela.” Cultural critique 30 (1995): 33-70.

[1] Contemporary writers like Jack Burnham, writing in 1968, argue that this marks a shift “from an object-oriented to a systems-oriented culture. Here change emanates not from things but from the way things are done,” Jack Burnham “Systems Esthetics,” Artforum, September 1968; South here refers to a broader reorientation along the lines of Joaquin Torres García’s provocation that “Nuestro norte es el sur,” or that our north is the south.

[2] There are echoes of Joseph Beuys here as well, who two decades later began his own series using lemons as batteries. Beuys knew of Grippo but the level to which he was influenced by Grippo’s earlier practice is still debated.

[3] This text is the translation used by an English-language version of Analogía I (first version) bought by Harvard Art Museums in 2010.

[4] Autopoiesis can be traced back to Maturana’s foundational 1959 paper, co-authored with Jerome Lettvin, Warren Mculloch and Walter Pitts, “What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s brain.” Before this paper, the retina was seen as a light receptor that simply transferred light into visual signals that were then processed by the brain. What Maturana et al. showed was that, after implanting an electrode onto the optic nerve, there were feature detectors that processed visual information directly in the retina itself, prioritizing for the frog visual recognition of small, intermittent quickly moving dots, which were termed “bug detectors.” The retina was no longer an objective sensor passing information along, but proof that the frog never neutrally saw. Instead, the structure of its eye determined and constructed the frog’s view of reality such that perception was not automatically representational. This is a type of boundary work, producing what would later be termed an operational closure onto the frog. Autopoiesis took this intervention further to show how the observer produces what they observe, moving beyond the assumption in this early article that there was an objective reality to which the frog did not have full access.