by George Shulman

Since the 2016 election, and during Donald Trump’s Presidency as well as its violent aftermath on January 6, commentators on the left have engaged in two related debates. One has concerned the danger posed by Trump’s rhetoric and policies, by his base, and by the extra-parliamentary right. This debate involves contrasting assessments of the future of the Republican Party, and of the durability of the hegemonic center that has ruled American politics from Reagan to Obama. Running parallel is a second debate on the left, and intensified since the summer, about the meaning of the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) and the massive inter-racial protests it organized last summer, but also about the potential of the Democratic Party as a vehicle of social change. These debates involve judgments of the character of American political culture and claims about the fluidity or rigidity of its manifest polarization. At stake are contrasting visions of our political moment. One vision, influential if not dominant, implicit if not always explicit, circulates through Democratic Socialists of America and Jacobin, and has been articulated by notable commentators like Samuel Moyn and Corey Robin in The New York Times and The New Yorker. Since 2016 it has depicted our political moment as both reflecting and continuing an ongoing impasse in politics and ideology. I support a contrasting vision, which also circulates through activist and academic circles on the left, and which depicts our moment as a fraught interregnum bearing both a real danger of an authoritarian or fascist turn, and, incipient possibilities of radical change. While the trope of impasse presumes the reconstitution of the hegemonic center ruling American politics since the 1980s, the trope of interregnum imagines both breakdown and transformation.

I would begin by noting the elements of the orientation I am trying to capture with the trope of impasse. First, it has criticized ‘alarmism,’ and consistently minimized the sense that Trump’s presidency, his base, and the Republican Party posed dangers beyond historic patterns of harm. Second, it has minimized the extent and grip of racism, misogyny, and polarization in the political culture of whites and in general it discounts the power of political language and the potency of irrationality, in order to defend the premise that ‘common material interests’ (and demographic change) can and will underwrite a multi-racial, progressive, majority coalition. On the basis of that organizing fantasy, third, it attributes the character of the Democratic Party only to cowardice and corruption, bred by neoliberalism and elite complacency, and it has discounted how the party, as currently constituted, could undertake change more radical than tinkering. Fourth, it has imagined each party absorbing its radicalizing elements, thereby sustaining the hegemony of established elites. It expects that an ideological political center will be reconstituted, and that American politics will remain trapped in the deep structural impasse that it claims Trump merely manifested and never ruptured. The overall effect of such arguments, over the last five years, is to emphasize the undeniable inertial power of historical patterns and institutions, but diminish their contingency, fragility, and mutation. Such arguments minimize our sense of both danger and possibility, and magnify our sense of historical stasis. Though we hear an assumption that demographic change promises a brighter future, if only the Democratic Party supported truly progressive candidates, the repeated conclusion over five years is that the Trump moment and Biden’s election only continue the “interminable present”—the structural intractability and discursive paralysis—depicted by the academic left since the early 1990s.

We cannot definitively validate, or decisively disprove, these claims and anticipations, both because “evidence” also warrants contrasting interpretations, and because assessments of the strength or weakness of a president, a movement, or a party concern objects whose character and power depend on actions that can and do remake political reality, whether by unexpectedly shattering a consensus, contesting entrenched power dynamics, or mobilizing unforeseen support. By foregrounding that sense of contingency, I would raise questions about each element or step of the “impasse talk” I am trying to identify, and propose instead how the trope of ‘interregnum’ better grasps the danger and the possibility in our recent history.

My avowedly arguable premise is that politics cannot return to the neoliberalism and racial retrenchment of the last fifty years, and that post-Reagan conditions of political impasse cannot continue, either. Instead, I would propose that American politics has entered what Antonio Gramsci called an interregnum, in which the old gods are dying, the new ones have not yet been born, and we suffer ‘morbid symptoms.’ Though his Marxist teleology assured him which was which, we cannot be so confident about what is dying and what is emergent. For the last year manifested indigenous forms both of fascism, and of radical possibility, as enacted by M4BL and the multi-racial protests it organized and led. Each was incipient or inchoate, and each was amplified by COVID-19, one by the gross racial disparity and state abandonment, the other by manic denial of its mortal impact and political implications. Each rejected neoliberalism, each overtly named the centrality of race, each bespoke the extent to which liberal democracy has been hollowed out, each scorned the party system as failed representation, each refused the idiom of civic nationalism and its narrative of incremental progress, each depicted conditions of crisis and decisive choice. But the crystallization—or cooptation—of each emergent possibility is contingent, not only on organizing by white nationalists and abolitionists on streets, in localities, and by elections, but also on fate–ful choices by the Democratic Party about its policy and rhetoric.

To anticipate, I propose that changes in both cultural landscape and party politics preclude reconstitution of the impasse that has arguably characterized American politics at least Reagan, and instead have opened an interregnum in which mobilized and antagonistic political constituencies—70% of whites, in one party, increasingly committed to minority and racial rule, facing a party increasingly committed to multi-racial democracy—see decisive choices shaping antithetical futures. If the question posed by the developments on the right is how to distinguish the danger of fascism from minority rule committed to white supremacy, the question posed by developments on the left is whether the radicalization on the streets since last summer, and danger from the right, engender a significant modification of liberal nationalism on the order of a third reconstruction. I would thus intensify both danger and possibility by amplifying the contingencies—and the rhetoric—that can interrupt, inflect, or transform inertial patterns.

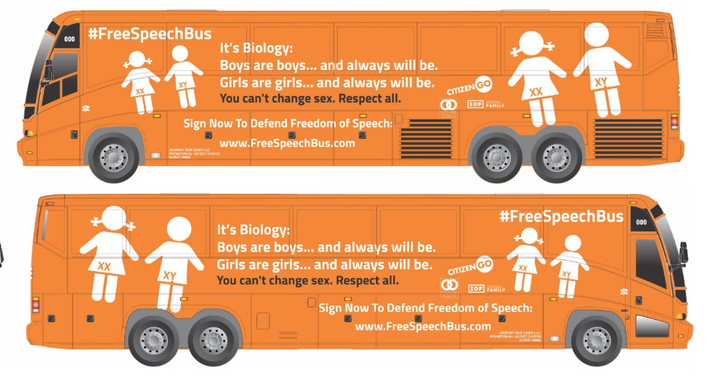

On the one hand, Trump was not repudiated in the 2020 election; he achieved a historic mobilization of working class, rural, and non-college educated voters to forge a coalition with explicit evangelical and capitalist elements, a long-sought Republican Party project, but he did so by disavowing creedal or civic nationalism, which had been the hegemonic rhetorical center that has long contained partisan difference. An explicitly anti-democratic and racially exclusionary Republican Party, no longer even evoking universalistic language, consistently won down ballot, protecting control of most states and redistricting, while retaining domination of the Supreme Court and the advantages bestowed by the constitution in the Senate and Electoral College. Roughly 70% of white voters, 40% of the electorate, deny legitimacy to the 2020 election, support the capitol invasion, and endorse not only voter suppression but overturning elections that Democrats win. Given the institutional grammar controlling elections, it is likely that a radicalized Republican Party will retake the Senate and perhaps the House in two years, and then win the Presidency in four years–unless the Biden administration produces tangible benefits clearly linked to electoral campaigns in states and nationally. Though a huge majority in public opinion polls support ‘bipartisanship,’ a default politics of ‘return to normal’ only allows the parliamentary obstruction that assures Republican electoral success. In turn, that success would cement an anti-democratic project of avowedly minority rule to protect authentic Americans from displacement, i.e. the native form of fascism that Du Bois and de Tocqueville–both seeing the imbrication of class rule, racial caste, and nationalism–called ‘democratic despotism.’ The newest iteration will amplify those inherited patterns, but in unprecedented ways it will abandon the universalist (creedal or civic) language that has both justified historic forms of domination, while also authorizing and yet containing protest against it.

On the other hand, experience of COVID-19 and last summer’s massive protests fostered notable shifts in how whites view both endemic racism and state action, opening unexpected and perhaps unprecedented possibilities for progressive politics. What some call a third reconstruction or new New Deal is now spoken of in ways that no one could have imagined even 6 let alone 12 years ago, and yet, importantly, it is also a political necessity. For the democratic coalition that elected Biden must address the suffering and rancor, as well as the political infrastructure and constitutional bias, that sustains its adversary, or it will become an ever-losing minority party despite its majority support. But given the polarization in American political culture –around race and gender, membership and immigration, the meaning of “America,” citizenship, and freedom, how can and should an openly social democratic and race-conscious approach be legitimated and narrated? That is the question of rhetoric, as Aristotle defined it: what are the available means of persuasion? Working through recent debates on the left will clarify possible answers.

The impasse argument

The first point of debate has been how to understand Trump’s electoral appeal and presidency, which has involved contention about naming -was Trump continuing conventional Republican goals (tax cuts and judges), or was ‘the F word’—fascism—appropriate to signal a mutation or intensification of inherited cultural and political patterns? These questions required judging the ways in which Trump simply repeated, or also modified, the white supremacy–and patriarchy–foundational in American history. One position feared the effects of ‘exceptionalizing’ Trump, which made him seem an anomaly in our history, rather than credit the racial and misogynist roots of his rhetoric and style, and rather than anchor his appearance in the failures of liberalism. The other position feared that ‘normalizing’ Trump would protect the ways that he represented a significant mutation of those historic patterns.

Against those who used the F word to signal those departures, two different kinds of claims were made, each normalizing Trump. One claim called Trump an inherently ‘weak’ president, as evidenced by his policy failures, whereas a contrary view traced how he was repeatedly thwarted by massive political mobilization. Likewise, by defining power only by what we “do” and not also by what we “say,” Trump’s actions were cast as conventional and ineffective, whereas a contrary view traced how overt racial rhetoric, performative misogyny, and the practice of the Big Lie were transforming inherited political culture and party politics. Anxiety about ‘fascism’ was thus dismissed on the grounds that Trump did not govern like European fascists and autocrats, rather than see him in relation to recurring but also mutating forms of what Alberto Toscano called “racial fascism,” entwining cultural mobilization, popular terrorism, and state violence.

The prevailing orientation, therefore, cast the “real” danger not as Trump or the right he was authorizing and mobilizing, but as the “alarmism,” even “hysteria” of those who used the F word. Why? Because the effect of “inflating” danger was to push the left to protect the regime of liberal democracy, as if it were the only and necessary alternative to fascism, whereas (and I agree) the failures and deep racial structure of liberalism in fact made Trump both possible and appealing. To reverse this argument’s logic, though, what is its effect? It dismisses those who see danger and precludes taking (the idea of) danger seriously. What is thereby being protected? If there really were danger from a growing and militantly anti-democratic right increasingly occupying an established political party, and if the U.S. had entered a version of a ‘Weimar moment,’ what would that mean? The left would have to re-imagine the cultural landscape (and working class) it has fantasized, and, it would have to decide if defending even the minimal terms of liberal democracy is a necessary to protect the possibility for radical possibilities. It would have to rethink the working class subject it is invested in sanitizing, rethink its assumption that hegemonic impasse will continue, and thus rethink its relationship to the loathed liberal object on which its future may depend.

The second point of debate involved the danger in the mobilization by the right, in increasingly networked and armed militias, in the alternate reality created by social media and FOX news, and in state and national sites of the Republican Party. The dangers have been consistently minimized by influential voices on the left, on the grounds that the extra-parliamentary right is not formally organized, and thus will be contained by the Republican Party. The capitol invasion and certification vote might have tested these claims, but influential judgment remains that the occupation ‘failed,’ as if that proved both the weakness of the right and the durability of the established order. Though the worst possible outcome did not materialize, that doesn’t mean the threat is not real and ongoing. The left faulted Biden for his fantasy of returning to normal that includes bipartisanship, but it has not traversed its own fantasy of the center holding until a progressive movement captures the Democratic Party and gains overt political power. Dramatizing a contrasting view, Richard Seymour responded to the capital invasion by inverting Marx: an “inchoate” and “incipient” fascism” has indeed appeared, as farce first; it can then reappear as tragedy. A first step has already occurred as the mobilized right has taken over and radicalized the Republican Party.

It is not consigned to irrelevance by demographics, as too many on the left assume; rather, Trump created a template for its resurrection. Indeed, his defeat further radicalized the party, even as it retained its grip on state and local governments. Given the electoral college, the rural bias in the Senate, voter suppression, and the composition of the Supreme Court, there is every reason to expect the party to remain committed to minority rule, and to electoral viability on terms that include overturning elections that Democrats win. No establishment element in the party is available for bipartisan consensus; every incentive encourages the party to obstruct Biden’s initiatives, diminish economic recovery, and prove that government is ineffective, thereby to feed the despair and rage that enable Republican majorities in Congress in two years, and a successor to Trump in four. Autocratic rule has been averted for the moment, but merely postponed, not forestalled. Alarm seems at the least prudent, and I would argue that prudence requires defending electoral (and so, liberal) democracy, not as an idealized alternative or revered object to defend against an alien form of despotism, but as a grossly flawed framework whose declared rights and recent advances nevertheless can authorize and enable emergent radical projects of democratization to develop further.

This broaches the third broad area of debate, concerning the character of public opinion and political culture. In simple terms, the election revealed that 72 million people, mostly white, across class lines, voted to reelect Trump–3 million more than in 2016, enough to have beaten Hillary in the popular vote and not only the electoral college. After the election, 80% of those voters remain convinced the election was stolen, a claim based on ‘disinformation’ that was taken as plausible because it confirmed prior racialized judgments about who is a legitimate citizen. Some of those voters were transactional, making a judgment on the basis of taxes and judges, but nevertheless, they knew they were voting for a candidate who refused to accept the peaceful transfer of power if he lost, as if Democrats could win only by fraud, i.e. by people of color voting. At issue is not only ‘denial of reality’ by enclosure within an alternate one, but mass investment in protecting white supremacy and patriarchy. The prevailing view of DSA and Jacobin would salvage this situation, to protect the vision of a class politics oriented by “material interest” rather than divided by the “identity politics” of race, gender, and nationalism. But for whites, class in the U.S. is lived through codes of race and gender, and by deep investments in both propertied individualism and nationalism. Indeed, a huge majority of whites has been wed to the death drive by the discourse of racial capitalism, aligning whiteness, work, and worth to masculinized self-reliance. Blocked grief at real losses has produced both the suicidal and manic features of melancholy. Rather than undergo mourning, many white men and women embraced death in the name of liberty, but they also are enraged, feel legitimized in their sense of victimization, and they are armed. The material realities of disease, precarity, and racial disparity must now include the invented reality of a stolen election, as well as the denial of reality embraced by the millions who voted for Trump. But the historic rationalism of the left, presuming the effectiveness of what Freud called the reality principle, prevents apprehension of the desires and fantasies–and so of the images and symbols–that constitute what class means in particular places and times.

I would call our historical moment an interregnum, therefore, partly because the historic marriage of citizenship and whiteness is being regenerated, not only as militias enact historic forms of popular sovereignty and local civic power, but also as the Republican Party increasingly recruits men and women of color into a newly emergent, multiracial and not only ethnic, form of whiteness. This anti-democratic form of ‘American democracy’ defensively asserts the individualism, popular sovereignty, and nationalism once taken for granted in the civic language that wed whiteness and citizenship, but now it is severed from even the pretense of universalist ideals and appeals. This zombie politics of the undead, this resurrection of American greatness may be dismissed as farce, but it will thrive and not truly die unless its premise—in gendered and racialized forms of individualism and resentment–is addressed, and unless its constitutional scaffolding is dismantled. This challenge has also prompted debates on the left about the Democratic Party.

The prevailing view, articulated by DSA and Jacobin, imagines a culture that is center-left in a readily accessible way, which implies that the only obstacle to a winning majority coalition is Democratic Party timidity, linked to the corrupt neo-liberalism of its established elites. If we recall that refusal to accept electoral norms has occurred before–when southern states seceded and then rejected open elections during reconstruction–it seems more plausible to say we have shifted from ‘polarization’ to a condition more like civil war, albeit so far a cold one, over antithetical visions of democracy and the future. Even if parliamentary stalemate persists, it reflects not so much structurally dictated foreclosure, as a condition of civil war whose outcome we cannot predict, because it is contingent on our action now.

In these cultural circumstances, the Democratic Party mobilized 8 million more voters and created the basis for a multi-racial coalition with some 30% of whites, more affluent and educated than not, and people of color across class lines. DSA and Jacobin still claim that Bernie Sanders could have won the election, despite the fact that even in the primaries he could not cross the 30% threshold, because he could not gain significant support from Black and Latinix constituencies (except in Nevada). The base of the Democratic Party, Black women, rescued Biden in the primaries because they credited the depth of racism and anxiety among whites across class lines, because they valued his appeal to competence, and, I would argue, because his profound (Catholic) understanding of grief linked mourning to public service in ways that really resonated with the Black church tradition. But in turn progressives and millennials still mobilized (in ways they did not for Hillary Clinton) because so many accepted Bernie Sanders’ dire judgment that we had indeed entered a Weimar moment in which the choice was really between Trump and democracy.

One incredible irony of our moment is thus that Biden’s reputation for moderation, his personal proximity to suffering, and his performance of a ‘common man’ version of a whiteness wed to decency not supremacy, were crucial to recruiting enough (suburban) whites to create a winning coalition with affluent progressives and people of color. Moreover, his first 100 days suggests that this persona may allow him to advance more progressive policies, perhaps a democratic version of Nixon going to China. Given our political culture, constitutional bias, and gerrymandering, the Democratic Party still needs both its moderate and its progressive wings if it is to fly, to use Cristina Beltran’s great metaphor, though this creates enormous parliamentary difficulty for progressive projects. And to complete the double bind, unless it produces benefits tangible to masses of people in the next two and four years, it is likely to be defeated electorally, but the actions that produce such benefits are likely to contradict the promises that are crucial to moderate voters.

Interregnum and Rhetorical Possibility

Rather than depict a durable center containing threats on the right as well as radical energies on the left, and rather than presume the readiness of working class Americans (across racial lines) to adopt a pointedly progressive political agenda, I see a darker and more dangerous situation in which a likely outcome is the victory of an openly anti-democratic Republican Party, anchored in an increasingly organized militia movement and a conspiratorial popular culture among the vast majority of whites, and recruiting enough people of color to appear nationalist rather than racist. Rather than moralize the character of the Democratic Party, I would emphasize that political culture among whites supports only some specific elements of the progressive or radical vision offered by the left, though to an uncertain degree some whites (across class lines) may be open to shifting affiliation. But tangible benefits are not self-evident in meaning and do not suffice to generate allegiance; rather, inferences from those benefits—that government can be effective for the many not the few, and that democracy is not a fraud—depends on the available means of persuasion. What are they? Which idioms might resonate, and with whom?

The symbiosis of Trump’s presidency and his base was made possible by the conjunction of defensive nationalism, racial retrenchment, and neoliberal precarity, the dominant strands in American politics since Reagan, which set the limitations of Obama’s self-defeating and disappointing presidency. But in ways the left has not credited, this conjunction reflects the failure of prior populist and progressive projects to address how citizenship is racialized standing and capitalism is always-already racial. The repeated failure of American social reformers to sever citizenship from whiteness, to show the price that whites and not only blacks pay for white supremacy, and thereby to join a class politics to an abolition project, is the ongoing condition enabling this iteration of American-style fascism. Conversely, a politically effective and durable response to Trump and his white base must address both precarity and structural racism, as twinned not separate. Progressives must show that separating whiteness and citizenship brings tangible benefits to those disposed by zero-sum racial logic to see only loss. But we also must explain what those tangible benefits mean–narrate their meaning–in ways that reattach profoundly alienated people—not only working class whites but millennials across class and race lines—to democratic ideals and practices they understandably deem fraudulent and/or exclusionary. Those ‘values’ are not manifestly valuable in a time of rampant cynicism, but must be turned from empty nouns into active verbs by political poesis and praxis that vivifies and enlarges their historic (and limited) meaning. Politics has entered an interregnum, though, not only because of danger on the right, but also because the conjunction of COVID and M4BL organizing has created just that possibility, by linking precarity and race in democratizing ways.

How might different ways of politically and rhetorically linking precarity and race address the danger of an emboldened and increasingly organized right? Aziz Rana, Robin Kelley, and many M4BL advocates have argued that the crisis in liberal nationalism and its creedal narrative, witnessed on the right and the left, is an opportunity to conceive a democratic politics no longer defined and contained by the nation-state. M4BL, drawing on traditions of black radicalism, is thus seen as a model of how social movements should sever projects of social justice even from a progressive version of civic nationalism and its redemptive narrative, to assemble instead coalitions that shape politics locally and influence policy nationally. On this view, radical social change requires not an over-arching national narrative, but a movement of movements, coalitions forged by transactional and strategic relations around intersecting issues, contiguous interests, and regional projects. The great benefit of this approach is to contest the settler colonialism presumed and erased by progressive versions of civic nationalism, and to instead foreground the patiently prefigurative politics that slowly but surely builds another world, a durable and vibrant res publica, within and against this one. Such ‘horizontalism’ may also offer a resilient practice of survival under conditions of a cold civil war, when political persuasion seems impossible, and mutual aid and mobilization seem paramount.

These arguments are credible and appealing, but I fear they cede state power to a mobilized right intent on crushing sanctuary cities, anti-racism insurgency, climate change activism, queer politics, and critical race curricula, let alone social democratic attempts to increase social equality and address racial disparity. They cede state power because they relinquish a large-scale (say national) effort to seek a majoritarian hegemony on behalf of a democratic horizon of aspiration, to legitimate equality, popular power in participatory practices, and through elections and truly representative institutions. I would argue that social transformation requires more than a coalition of constituent movements, which are always at risk of acting as narrowing interest groups; it requires hegemony, to denote the symbolic legitimation and organization of political power that at once advances and protects the constituencies it brings into relation as a majoritarian formation. Such hegemony requires symbolic or figurative language, an organizing vision and historical narrative, to explain circumstances, invoke a ‘we,’ and stipulate ‘what is to be done.’ For democratic ideas and participatory practices are not self-evidently desirable or legitimate; by praxis and imaginative poesis we turn empty nouns into embodied verbs, visible realities, rhetorically compelling objects, and durable affective attachments.

On the assumption that radical social change requires a persuasive idiom with broad appeal, my avowedly arguable proposition is for progressives to articulate a “third reconstruction” that, in Baldwinian terms, publicly reckons with the historical legacy, institutional features, and cultural meaning of white supremacy, while in Gramscian terms, symbolizes democratic renewal through a ‘national-popular’ idiom aspiring to hegemony. Because the toxic character of civic life and prevailing devaluation of public goods is inseparable from endemic racism, a third reconstruction is not only a program of ‘reparations’ directed to the ‘wealth gap’ suffered by Black communities, but is also the means and the signifier of a broadly democratic reconstitution of social life. That reconstitution requires the use of state power and public programs to break the grip of oligarchy and caste, but its democratic integrity depends on ongoing ‘movement’ in every locality and across of range of issues, to bear witness to historic injustice and present injuries, to sustain non-state infrastructures of mutual aid, to pressure elites, and to create stages on which people can see themselves assembled, enjoying civic life and public things. But as the freedman bureaus during the first reconstruction indicate, the survival, let alone vitality of any ‘democracy-from-below’ requires a state that challenges local tyrannies and supports insurgencies, which in turn requires a ‘national-popular’ idiom that shows the relevance of democratic ideas to people rightly cynical about them, and that recruits (some or enough of) those who inhabit the “non-intersecting” reality that is the legacy, not only of Trump, but of the failed liberalism that made him possible.

Rather than recuperate the tired teleological narrative of progress, the trope of a “third” reconstruction emphasizes two prior but “splendid” failures, as Du Bois put it, to suggest a revolutionary experiment to make anew, the contingency of any victory or accomplishment, and the necessity for ongoing popular struggle with entrenched forms of power. We cannot know if such language could achieve hegemony until and if it is genuinely attempted. In this interregnum, when we do not know what is in fact dying–is it white supremacy or democratic possibility?–drawing on ‘national-popular’ or vernacular idioms seems necessary to reckon finally with the past, project a potentially common horizon, and thereby protect the very idea of a democratic, multi-racial politics. Failure does not mean a return to neo-liberal impasse, but an opening for an aspirational fascism to shift from incipience and farce to resurgence and tragedy.

George Shulman teaches political theory and American Studies at the Gallatin School of New York University. In 2010, his second book, American Prophecy: Race and Redemption in American Politics, won the David Easton Award for best book in political theory. He is currently working on a book entitled Life Postmortem: Beyond Impasse.