by Darren Byler

When Tursun decided to become a police officer in 1992, it seemed like the opportunity of a lifetime.[1] The state had just opened up a pathway for Uyghur high school students who excelled in Mandarin and political theory to study in elite policing academies and other schools in Eastern China (Grose 2019). At the end of the 6 years of training, a secure posting in an urban police department was virtually guaranteed. For someone who came from a village near China’s border with Kazakhstan, it promised a way out of rural poverty and, Tursun believed, a way of creating a more just society. But at the time Tursun was not yet fully aware of the fact that resource disputes between native Uyghurs and newly arrived Han settlers in the desert oases of Southern Xinjiang was one of the reasons why he was being trained to join the Xinjiang police force.

As I write in my book Terror Capitalism (2022), the intensification of policing in Northwest China, coincided with a development of a Han migrant settlement campaign to “Open up the Northwest.” This campaign which centered on natural resource extraction and industrial farming in the ancestral lands of the Uyghurs in the Southern part of the region precipitated flashes of violence related to land theft, systemic ethnic discrimination and new restrictions on Uyghur autonomy. In April 1990, in the community of Barin, a village near the city of Kashgar, tension over access to irrigation and land, boiled over into a brief farmer-led Uyghur insurgency (Roberts 2020). A detachment of armed police and military arrived within several days and opened fire on the farmers who occupied a community government building armed primarily with hunting rifles and farming tools. Those who I interviewed who were in the surrounding communities at the time said that bodies of the insurgents were loaded in trucks and taken away.

But there was a more fundamental change in the community beyond the disappearance of those directly involved in the uprising. Now, it appeared, that state authorities viewed the majority of Uyghur villagers in the surrounding communities as “troublemakers” simply because of their ethnicity and their proximity to the farmer uprising. Over the next several months nearly 8000 people were officially arrested (Roberts 2020). Vast numbers of people in the prefecture were forced to attend self-criticism sessions and study political ideology. They were asked to search their hearts and consider how they might have contributed to a lack of loyalty to the Party’s mission to develop and extract regional economic resources for the benefit of “the masses.” Did they consider Uyghur possession of their own lands more important than contributing to the wealth of the county? Didn’t they know that when they questioned the settlement and land distribution policies they were challenging the correctness of the Party?

Uyghurs in this community said that it felt like the Maoist ideological campaigns that had ended with the Cultural Revolution in 1976 were returning, but that this time they were pointed not at “counterrevolutionary” enemies who supported the “capitalist road,” but rather at Uyghurs who opposed the preferential treatment for Han settlers in the new state-directed export-oriented capitalist economy. They came to understand that they were seen as impediments to the development of what was now becoming an internal settler colony in China’s post-Cold War economic rise. In the new social order, civilization itself was equated with state-led market development. Over the next two decades Uyghurs came to see how a discourse of terrorism could be used to deem them both an internal enemy of the state and of the civilized world in general if they opposed this disempowering form of development (see also Fischer 2013). As always-already potentially terrorists Uyghurs could be framed by an internal otherness that justified drastic policing measures and eventually led to mass internment and imprisonment. Over time, the specter of the terrorist produced a fear-driven economic and political logic for the state, and the corporations it partnered with, that resulted in billions of dollars of investment in counter-terrorism surveillance in Uyghur communities.

As social theorist Michael Dutton has argued (2005), since policing in China emerged out of this revolutionary context of the 1950s, rather than, for example, the hunting of slaves as in the United States or the pacification of the working class in Britain, Chinese policing was organized primarily around a friend or enemy distinction—with “friend” (pengyou) figured as the revolutionary masses, or the people, and the enemy figured as foreign imperialists and domestic counterrevolutionaries. Importantly, because of the revolutionary impulse of Chinese policing the latter category of enemies could at times be rehabilitated through education and carceral punishment if they were able to recognize the liberatory potential of socialist mass struggle.[2] They were, regardless of their ethnicity, still potential “compatriots” (tongbao) in the multi-national Chinese revolutionary project. But what happens when such compatriots are deemed “separatists” or “terrorists”? This is the central question this essay will explore.

Mao’s 1957 essay on the “Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People,” supplies a rationale for making fine distinctions between enemies and wayward friends. This sorting and productive capacity of policing as a tool of educating and persuading provided an opening for “thought work” (sixiang gongzuo)—communal struggle sessions where those deemed out-of-line proclaimed self-criticisms and professed their new understandings of Maoist thought. Such targeted individuals were often placed under concentrated surveillance in reeducation and labor camps as internal enemies, or at a minimum, they were stigmatized in their home communities and they were viewed as compatriots who had failed in their revolutionary resolve. Their fellow community members were tasked with observing their progress, looking for any slip-up in submissive attitudes. At the end of the Maoist campaigns in 1976, the spectrum of what counted as friend was expanded to include former political prisoners and these “wayward friends” were reunited with the masses through a process called “rehabilitation” (pingfan). This process was organized by “rehabilitation committees” (pingfan weiyuanhui) who considered formal appeals those on watchlists and petitions of family members on their behalf, and organized periods of close surveillance in the communities where the wayward friends returned.

Throughout the 1980s democracy movements, particularly on college campuses, accompanied an emergence of capitalist production and export-oriented economy. And for a time, it appeared as though the category of the internal enemy was on the verge of disappearing. Then in 1989 that prospect collapsed with the mass killing in Tiananmen Square and subsequent disappearances of thousands of democracy activists—mostly Han college students, but also Uyghur and other ethnic minority young people—all of whom were deemed internal enemies of the state.

With the violence in Barin in 1990, as noted at the beginning of this essay, a further reorientation of “enemies” and “friends” distinctions toward Muslims in Xinjiang demanded a new police force that was equipped to decode Uyghur opposition to the state—elaborating a new sub-category in the friend-enemy continuum—“separatists” (Ch: fenlie zhuyi zhe; Uy: bölgünchi)—and the threat it posed toward settler claims to possession of Uyghur lands (Tynen 2020). Over the next decade, teams of state workers, would be tasked with surveilling families in communities where discontentment was most pronounced. As one of these surveillance workers put it, “We worked for months on end without any days off, rummaging through the villages and homes of Uyghur farmers, making lists of names of so called ‘separatists’ and reporting their names to the upper-level officials. As human surveillance workers we searched people’s homes, sometimes even at late night hours, looking for any suspicious books that might be spreading a ‘separatist” ideology’” (Ayup 2022, 27).

In Xinjiang the term separatist, which emerged in Chinese state discourse in relation to Taiwan’s autonomy in the 1950s, rose to replace the Maoist term “counterrevolutionary” in the 1980s as changing cold war dynamics and the turn toward a market economy following Mao’s death made “national unification” (Ch: guojia tongyi) with Taiwan appear to be more of a possibility. The term was extended by Chinese state discourse beyond Taiwan to discussions in Tibet and Xinjiang in the 1990s in response to the rise to international prominence of the Dali Lama and Tibetan government in exile. As the Dali Lama garnered support in India and the endorsement of international celebrities, the Chinese authorities worried that the Free Tibet movement might spark a “ethnic separatist” revolt within China’s borders. This fear was given more force with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991 and the independence of the Central Asian republics. In Xinjiang these factors solidified a shift toward policing the perceived Muslim “separatist” threat (Becquelin 2000).

Chinese leaders viewed the Barin Uprising as a sign of Uyghur desires for greater self-determination. Increasing Han settlements in Uyghur majority areas had the benefit of both gaining access to natural resources, but also, as a result of the fracturing of the Soviet Union—China’s long-term rival—building new avenues for Chinese markets in Central Asia and attending to the resource needs of Chinese manufacturers. These economic and geopolitical factors precipitated a change in policing in Xinjiang—a change that Tursun, the Uyghur police officer whose story begins this essay, would be a part of.

But, of course, historical changes are difficult to recognize at first, especially when they are orchestrated behind closed doors in the headquarters of the Ministry of State Security. About the time Tursun graduated from the police academy another major incident occurred. In 1997, near his home village in Ghulja, Uyghurs protested the breakup and arrest of a youth organization that taught Islamic and Uyghur moral behavior and traditions (Roberts 2020). Although the state denies this figure, it is likely that more than 100 Uyghurs were shot in the streets and more than a thousand more were taken away, arbitrarily detained in an opaque process that ranged from “reeducation through hard labor” in camps to more formal imprisonment. Some Uyghurs fled across the border to Central Asia, eventually fleeing to Afghanistan to escape extradition back to China only to be turned over to the U.S. military and sent to Guantanamo Bay where they were eventually released without charge.

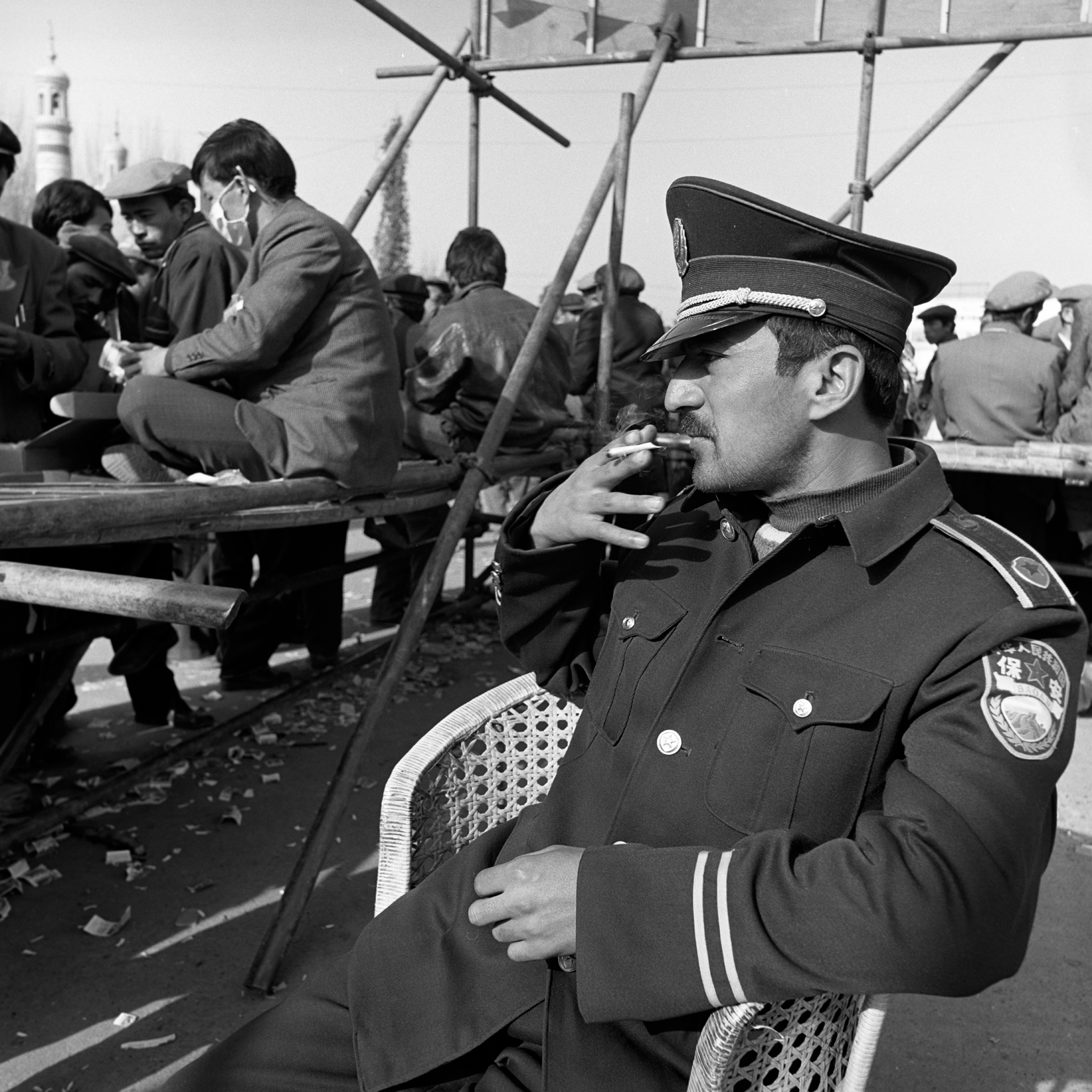

When Tursun graduated with a degree in policing science in a Chinese-language policing academy the next year, he found himself thrust almost immediately into a hunt for phantom “separatist gangs” like the protestors who organized the marches. Throughout the Xinjiang police force, officers were tasked with implementing a “hard strike campaign”—part of a series of campaigns that would culminate, as I will explain below, in the “People’s War on Terror.” One of Tursun’s roles was to act as interpreter and translator, turning Chinese language policing science and directives into action in Uyghur communities by interpreting Uyghur confessions for Han police commanders. His beat was nearly exclusively in Uyghur neighborhoods and villages where he was often accompanied by a non-Muslim partner. He was to be the eyes, ears, and voice of the state.

Then, almost immediately after September 11, 2001, a new category in the friend-enemy continuum was introduced in Chinese policing rhetoric and theory. “Now we were supposed to call them ‘terrorists,’” Tursun told me in Uyghur, interjecting the Chinese word for “terrorist” (Ch: kongbu fenzi). “The vast majority of the groups we found were not separatists or terrorists at all. These were labels we gave to people who committed other crimes, or didn’t commit any crime at all, but who had no one to defend them.” As Gardner Bovingdon (2010) shows in an encyclopedic index of state documents from this period, terrorism charges proliferated in the 2000s with crimes as minor as a Uyghur neighbor accused of stealing a cow from a Han settler being labeled a terrorist activity. Eager to associate the “Uyghur problem” with the Global War on Terror, Chinese officials removed most instances of the term “separatist” from official histories of the 1990s and replaced them with the term “terrorist.” The new term had a different utility. In the post-9/11 context “terrorism” allowed the Chinese state to position itself as an ally to the West and Central Asian republics in the global war against so-called Islamic “extremism” and terrorism. By offering Central Asian republics policing technology, training, and intelligence in addition to infrastructure development projects and trade incentives, Chinese authorities used a security framework to build strategic economic and political relationships that would eventually turn into its ambitious Belt and Road Development Initiative.

Even more importantly, back in Xinjiang the terrorism label also hardened the “enemy” categorization of Muslims who opposed state-directed development and settlement of their land. No longer were “enemies” viewed simply as counterrevolutionaries or separatists, that is, those who were nevertheless compatriots and who could potentially be rehabilitated.

For Tursun, “discovering” hidden terrorists became a primary objective. Police units that identified such “gangs” were given large rewards. From Tursun’s perspective, it was as though the policing came to serve a larger disinformation campaign. By “discovering” terrorists, the police units fulfilled their obligation in the crackdown and concealed the structural factors that caused Uyghur protest in the first place. Over and over again Tursun observed or participated in turning informants, forcing them to identify “terrorists,” and using them to break up community networks:

We had a policy which encouraged people to spy on each other. Often they did this for money, or because we threatened them or their families. Of course we knew that a lot of our tips were just false accusations. Some people did that for money, while some people did that to take revenge on others. But we would arrest people regardless of the truth of information. For example, if four or five people gathered together for activities such as visiting a friend or attending a funeral and someone said it was an illegal gathering to teach Islam or plan violence we would arrest everyone who attended and label the host the ringleader. Everyone knew that at a funeral, people are required to conduct religious rituals. This is normal since Uyghurs are Muslim. But the spy would exaggerate and say it was extremist or terrorist. People who were being accused have no way to prove that they are innocent. Often they ended up being sentenced to 4 or 5 years in prison or “education through hard labor” camps. The informant was given money and we received our commendation. This was so common.

Tursun found this form of state violence morally repugnant. “Most Uyghurs I met were disgusted by the very idea of terrorism,” he said, “They wanted a peaceful life, a better world for their children.” But he worried that a generation of Uyghur young people who grew up in this atmosphere, where disappearances of Uyghur community leaders became so common, would lash out. Indeed, as Sean Roberts has shown, in some instances the “terrorism” label became a self-fulfilling prophecy (Roberts 2020). While not the norm in Uyghur crimes labelled as terrorism, in a handful of cases in 2013 and 2014, Uyghurs did attack Han civilians in organized suicide attacks. These specific attacks did appear to meet international standards of what constitutes a terrorism crime—though even they may be more appropriately understood to be horrific incidents of mass murder that arise from colonial circumstances. Soon after the terrorism label arrived, Tursun tried to quit his job as an officer. He was told that he needed to serve at least 10 years before he could even begin to consider early retirement. Because he had been granted access to state secrets, quitting would be a slow process. He was told he could be arrested if he quit without a justifiable excuse.

Over time it became clear that the hopes Tursun had for criminal justice reform would never happen. When he first joined the Public Security Bureau he thought that the presence of college-educated Uyghur officers would help improve the situation. Instead, he saw his fellow Uyghur officers, many of them who he had known for over a decade be worn down by the system. He saw many turn toward alcoholism and become withdrawn from their families. Uyghur police officers were treated with deference and fear by other members of the Uyghur community. It was good to have a friend who was a police officer, since the officer might be able to protect them from the counter-terrorism system by vouching for them. But this friendship was a guarded, political relationship. After all it was a relationship with the eyes and ears of the state, and what stood between being deemed a terrorist-enemy and a friend.

Even though Tursun was eventually able to leave the Bureau and, through a loophole in the system, escape to Europe, he knows that had he stayed he would have been pressed into service of the mass internment camp system that was put in place in the mid-2010s. “At this point I can’t say that every Uyghur retains some aspect of their humanity,” he said quietly. “Some Uyghur officers will do anything to show their loyalty to the government, no matter what kind of suffering they cause. All they care about are the benefits and power they get from their position. I know there are some Uyghur police who feel bad about the torture that Uyghur detainees are going through now in the camps, but the percentage of those who care are not that high. At this point they are numb.”

Although policing in China began in a revolutionary moment and was driven at first by Maoist “counterrevolutionary” politics, in the 1990s and 2000s in Northwest China it gave way to colonial-capitalist and counter-terrorism logics that participate in familiar forms of ethno-racialization and dehumanization found in post-9/11 policing systems and counter-terrorism around the world in which Muslims are racialized as deviant others. Although, they emerge from different histories, extrajudicial detention and surveillance of refugees and other unwanted populations from Kashmir, to Palestine, to France and the United States produce similar effects at differential scales (Byler 2022). As China was pulled into a global capitalist economy and the logic of developmentalism settled on a Han-centric mythos of China’s reemergence as a global power, the revolutionary multi-national inclusiveness of China’s framing of political struggle was deeply diminished.

In 1990s China the Maoist frame of friends and enemies was folded into a concern with “unifying” the country to benefit the masses—understood as the Han majority to the East and the Han settlers who came to the frontier to claim resources for them. Here “friends” came to be those who supported this project, and “enemies” became Uyghur “separatists” who protested these settler claims. Then, in the 2000s, the discourse of Uyghur “separatist” enemies hardened into “terrorists.” Over time, the possibility of full citizenship as “friends” has severely narrowed for Uyghurs. Since 2017, hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs have been warehoused in an expansive prison system for alleged terrorism crimes (Byler 2022). Hundreds of thousands more whose “extremism and terrorism activities are not serious” have been placed in internment camps for reeducation (United Nations 2019). After an intensive period of Chinese language assimilation, ideological indoctrination, and brutal punishment, they are placed in securitized factories where they labor apart from their families and under intensive forms of technological and human surveillance. Together these carceral systems result in the largest internment of a religious minority since World War II. Uyghurs, as always-already “enemy” terrorists have become internal others, marking a turn from compatriot rehabilitation to new policing technologies of control and incarceration derived from global models of the war on terror.

Darren Byler is an anthropologist and Assistant Professor in the School for International Studies at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, British Columbia. He is the author of Terror Capitalism: Uyghur Dispossession and Masculinity in a Chinese City and In the Camps: China’s High-Tech Penal Colony. His current research is focused on policing and carceral theory, infrastructure development and global China.

Works Cited

Ayup, Abduweli. 2022. The Detainment Factory: A Memoir. Manuscript.

Becquelin, Nicolas. 2000. “Xinjiang in the Nineties.” The China Journal 44: 65-90.

Bovingdon, Gardner. 2010. The Uyghurs: Strangers in their own land. Columbia University Press.

Byler, Darren. 2022. Terror Capitalism: Uyghur Dispossession and Masculinity in a Chinese City. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Dutton, Michael. 2005. Policing Chinese Politics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Fischer, Andrew Martin. 2013. The disempowered development of Tibet in China: A study in the economics of marginalization. Lexington Books.

Grose, Timothy. 2019. Negotiating Inseparability in China: The Xinjiang Class and the Dynamics of Uyghur Identity. Hong Kong University Press.

Roberts, Sean R. 2020. The War on the Uyghurs. Princeton University Press.

Tynen, Sarah. 2020. “Dispossession and displacement of migrant workers: the impact of state terror and economic development on Uyghurs in urban Xinjiang.” Central Asian Survey 39.3: 303-323.

United Nations (UN). 2019. Information Received from China on Follow-Up to the Concluding Observations on its Combined Fourteenth to Seventeenth Periodic Reports. 8 October. Geneva: Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. Available from: undocs.org/CERD/C/CHN/FCO/14-17.

References

[1] Although “Tursun” is now living in Europe, he has asked me to use a pseudonym to protect his identity from Chinese authorities and the stigma associated with his past work as Xinjiang police officer.

[2] Dutton (2005) relies quite heavily on Carl Schmitt’s theorization of political struggle in his analysis of Chinese policing. Scholarship on Maoist intellectual and grassroots history since Dutton’s important contribution to Chinese political theory shows that the generative potential of Maoist framings of revolutionary struggle demands a re-examination of Schmitt’s work and the fascist context it reflects.