Saul Bellow’s Political Soul

by Ben Rogerson

~

What connects literature and politics? On first glance, the editors of A Political Companion to Saul Bellow, an eight-essay collection in the series Political Companions to Great American Authors, offer incongruous answers. For the series editor Patrick Deneen, American literature hosts the “teaching of the great authors,” which amount to a “democratic public philosophy” that meditates on issues of perennial political interest (vii)1. Conversely, Lee Trepanier and Gloria L. Cronin, the volume’s editors, initially provide a historicist justification for why Bellow warrants a political companion, explaining that his fiction “captures the general political shift in mainstream America from liberalism to conservatism” (1). But their introduction concludes on a counterintuitive note, in which American literature teaches us about democracy, or politics more generally, to the extent that such literature isn’t political. Any study of Bellow’s fiction inevitably collides with his “genius,” and the realization that “neither his work nor his biography can be reduced to a purely political investigation” (7). After all, he is an “artist,” not an ideologue, and his fiction was ultimately concerned “‘not [with] politics but [with] the soul’” (Gordon qtd. 7). Great American authors may be great teachers, but some mysteries must remain.

A Political Companion to Saul Bellow does not announce the intellectual positions that it has inherited from Bellow’s era and which clarify aims that are, on one hand, public and pedagogical and, on the other, private and aesthetic. But these positions are familiar to readers of Stephen Schryer’s recent book Fantasies of the New Class, which argues that Bellow’s fiction closely articulates a literary and cultural politics that parallels the changing practice and ideologies of the “new class,” or America’s rapidly-expanding professional middle class2. Following World War II, new-class intellectuals such as Bellow, Lionel Trilling, and Mary McCarthy began to distrust the prevailing practices of “social trustee professionalism,” whose “technocratic pretensions towards social reform” seemed to only further ossify the bureaucratic welfare state (Schryer 6).  Compared to “institution building” (4), the response of new-class writers and intellectuals has often been mistaken for a “retreat” into the “purely private aesthetic sensibility” of the autonomous artist (Schryer 5)—what the Companion editors celebrate as Bellow’s “‘soul.’” But Schryer argues that this apparent retreat instead signified a new Arnoldian form of “public service” that “[favored] a different, humanistic model of cultural education oriented toward the educated middle class” (6). In this model, the very “example” of a new-class intellectual—in Bellow’s case, the aesthetic complexity of his literature—presumed a political efficacy capable of correcting the narrow materialism of American society (and capitalism in particular). Even as his politics shifted rightward in the 1960s, Bellow did not abandon the methods of new-class pedagogy. While increasingly suspicious of “intellectuals’ will-to-power,” he still saw the ongoing need “to reconquer the cultural center, using it to reeducate the American public” (Schryer 24).

Compared to “institution building” (4), the response of new-class writers and intellectuals has often been mistaken for a “retreat” into the “purely private aesthetic sensibility” of the autonomous artist (Schryer 5)—what the Companion editors celebrate as Bellow’s “‘soul.’” But Schryer argues that this apparent retreat instead signified a new Arnoldian form of “public service” that “[favored] a different, humanistic model of cultural education oriented toward the educated middle class” (6). In this model, the very “example” of a new-class intellectual—in Bellow’s case, the aesthetic complexity of his literature—presumed a political efficacy capable of correcting the narrow materialism of American society (and capitalism in particular). Even as his politics shifted rightward in the 1960s, Bellow did not abandon the methods of new-class pedagogy. While increasingly suspicious of “intellectuals’ will-to-power,” he still saw the ongoing need “to reconquer the cultural center, using it to reeducate the American public” (Schryer 24).

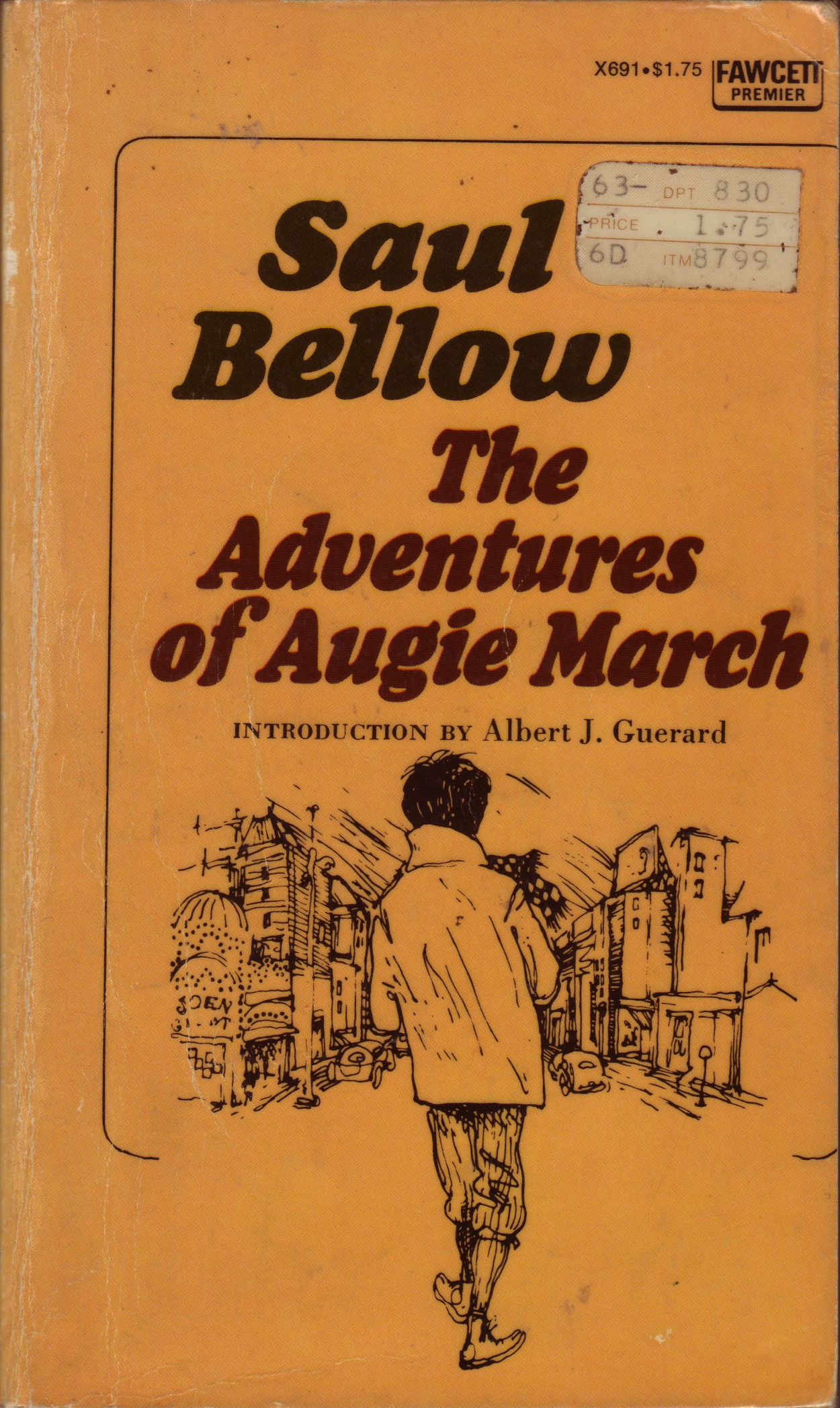

Without necessarily embracing the editors’ conservatism, intimations of the new-class pedagogical project seem to suffuse many of the volume’s essays. For instance, Judie Newman argues that Bellow’s neoconservative reputation has concealed the impact of Trotskyism on his early political and fictional writing. That impact is never greater than in short stories such as “The Hell It Can’t” and “Two Morning Monologues,” as well as his first novel The Dangling Man (1944), which question American intervention in World War II and the ongoing viability of capitalism. By 1942, Bellow’s “threshold” short story “The Mexican General”— a fictionalized account of Bellow’s 1940 trip to Mexico to meet Trotsky, who was assassinated beforehand—makes clear that his Trotskyite enthusiasms were waning (20). Thus, a subsequent novel such as The Adventures of Augie March signifies not only an artistic but also a political maturation; its early drafts more explicitly displayed Bellow’s nascent social democratic politics. But the essay concludes by giving the final word to a familiar idea. In “Mosby’s Memoirs,” a 1968 short story that reflects on Bellow’s political past, the writer “satirizes both sides of the political spectrum” in order to teach readers, it would seem, to recognize the naïveté of political ideologies—socialist, conservative, or otherwise (24).

Newman’s efforts notwithstanding, the neoconservative turn figures prominently in two essays on Mr. Sammler’s Planet, a 1970 novel that uses the Holocaust to frame shifts in Bellow’s political thought. Accepting the series’s moral-pedagogical challenge, Victoria Aarons explores the insights that Sammler and The Victim (1947), Bellow’s second novel, provide into “how to live in a post-Holocaust world” (134). For instance, Sammler, whose protagonist is a survivor, teaches us “that words, uttered irresponsibly, distort essential truths” (147). The novel charges Hannah Arendt with such irresponsibility, as she needlessly theorizes Nazi criminality—her famous conclusion about the banality of evil—“at the expense of clear, straightforward reckoning” (146) and, ultimately, “basic human decency” (149). But at the very least, Aarons’s conclusions are striking for their unreservedness. After all, Sammler is the novel whose only African American character is not only a pickpocket who steals, among other things, Social Security checks from elderly whites, but who maniacally pursues the protagonist so he can expose himself in animalistic fashion.

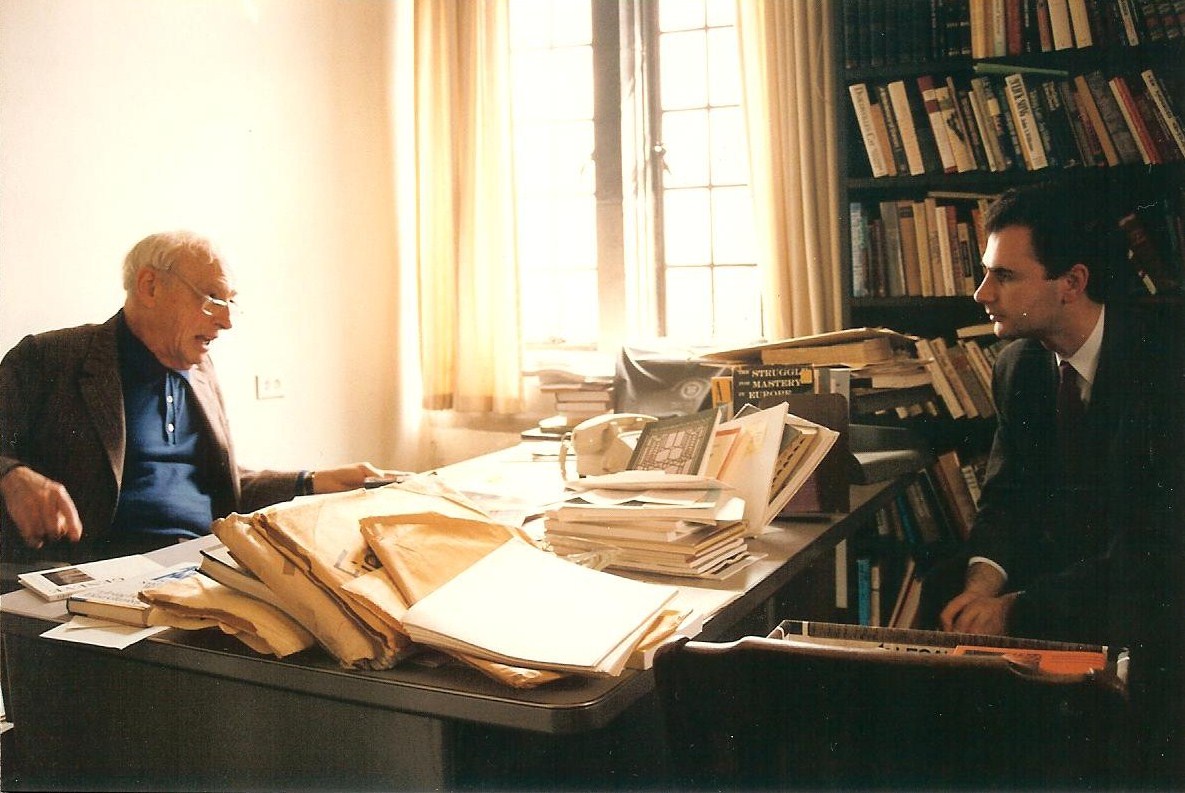

By contrast, Andrew Gordon’s essay acknowledges how Sammler deploys the Holocaust as part of a political polemic. In the novel, the pickpocket’s theft and self-exposure bookend Sammler’s visit to Columbia University to deliver a lecture on the British Left in the 1930s,  which Gordon compares to Bellow’s 1968 lecture at San Francisco State University on the role of writers in the academy. In both cases, New Left radicals rudely heckle the speakers, accusing each one of being an “effete old shit [who] can’t come.”3 (In fact, it was the Mexican-American writer and political activist Floyd Salas who heckled Bellow). More importantly, Gordon argues that Bellow exploits the differences between the two lectures in order to imply that fascistic tendencies within the New Left justify his own conservatism. In the novel, the student radical does not embarrass the self-assured, well-known, and combative Bellow during the Q&A; rather, Gordon points out that he victimizes an unknown and half-blind Holocaust survivor who has innocently mentioned George Orwell, another leftist guilty of breaking ranks.

which Gordon compares to Bellow’s 1968 lecture at San Francisco State University on the role of writers in the academy. In both cases, New Left radicals rudely heckle the speakers, accusing each one of being an “effete old shit [who] can’t come.”3 (In fact, it was the Mexican-American writer and political activist Floyd Salas who heckled Bellow). More importantly, Gordon argues that Bellow exploits the differences between the two lectures in order to imply that fascistic tendencies within the New Left justify his own conservatism. In the novel, the student radical does not embarrass the self-assured, well-known, and combative Bellow during the Q&A; rather, Gordon points out that he victimizes an unknown and half-blind Holocaust survivor who has innocently mentioned George Orwell, another leftist guilty of breaking ranks.

Two other essays primarily concern Henderson the Rain King, Bellow’s 1958 novel about an American millionaire whose spiritual search in Africa unexpectedly results in friendship with a tribal king. Carol R. Smith and Daniel K. Muhlestein stake out opposing answers to a single question: does this novel reinforce racist ideologies? Answering in the affirmative, Smith contends that Bellow’s latter-day anti-multiculturalism—his opposition to second-wave feminism and, especially, Black Power movements—realizes political trajectories initiated in his earlier fiction. As its protagonist rambles through deepest Africa, Henderson displaces “the history of the African passage with a history of the Jewish Atlantic” in order to produce what Smith calls an “assimilationist model of white America” (104). Jewishness is crucial to constructing such notions of “Americanness” because it signifies “elective immigration”—that is, Jewishness signifies a flight from European oppression (103). Following Toni Morrison, “Blackness” in turn necessitates the act of displacement because it persists as a troubling reminder of the “potentially disabling material circumstances”—enslavement and forced migration—that subtends American nation building and the transmission of liberal humanist values (106). Smith argues that Henderson ultimately attempts to nullify this racial unconsciousness through its symbolic geography. At the novel’s end, Henderson returns from Africa with a lion cub (itself the reincarnation of a dead African king) to realize renewal in the white snowy landscape of, of all places, Newfoundland.

~

In this model, the very “example” of a new-class intellectual—in Bellow’s case, the aesthetic complexity of his literature—presumed a political efficacy capable of correcting the narrow materialism of American society (and capitalism in particular).

~

Rather than the racialized lion, Muhlestein argues that the novel is preoccupied with a different animal—namely, the carnival bear from Henderson’s youth, and which he also recollects in the novel’s final pages. At first, this symbol seems only to confirm the presence of a carnivalesque aesthetic, in which the novel combines comic and grotesque elements to “torque” the “colonial library,” or those familiar tales of white exploration and evangelism in the heart of Africa (72). Deploying this aesthetic in scenes with King Dahfu and the Wahiri tribe, Henderson debunks the noxious ideology of the black Demonic Other so powerfully explored in Joseph Conrad’s fiction. But Muhlestein ultimately contends that the relationship between the carnivalesque and colonial politics is beside the point. Henderson is “not … a political novel per se,” a point on which Bellow insisted as well (96). Indeed, Muhlstein concludes that the novel’s “reason for existence” is purely vocational—the novel may use elements from the colonial library, but only incidentally, and only in order to “[facilitate] the creation of the carnivalesque” (96).

Like Muhlestein’s contribution, the cumulative effect of Ben Siegel’s essay on Bellow as a Jew and Jewish writer—an essay about how Bellow rejects the constraints of one “label” after another—is to grant the writer his self-proclaimed status as an artist whose obligations are to his vocation (47). Bristling at the “‘parochial’” description “Jewish writer,” Bellow called it the literary equivalent of “‘ghetto walls’” (qtd. 49). “‘No good literature is parochial,’” Bellow once claimed, because good literature “‘should appeal to anyone.’” Furthermore, Siegel has also described a writer who disavows ethnic labels as obstacles to becoming one of the ““great-public … artists” whose fiction reaches—and teaches—a mass readership (Bellow qtd. 50). As Bellow said in a 1971 interview, “what Americans want to learn from their writers is how to live.” And Richard Ohmann has noted that readers were on the same page, excited to play their part in this pedagogical project.4

In my opinion, Siegel’s brief sketch of how the writer conceived his relationship to his readership points to new directions for scholarship on Bellow—not for continuing the volume’s political-cum-pedagogical project as such, but for expanding the institutional context in which Bellow’s fiction and ideologies of professionalism circulate. Schryer typically addresses this writer-reader relationship through the university, the institution that educates the growing professional class that will comprise the mass readership for postwar writers. But this relationship is also an effect of another set of institutions, one which has garnered less critical attention—namely, the midcentury publishing industry, whose commercial success partly depended on promoting literary-pedagogical concerns complementary to those of the new class. Evan Brier has recently contributed to this discussion in A Novel Marketplace, his study of “postwar novel production” that suggests how publishers exploited “the genuinely felt alarm over the emergence of mass culture” in order to delineate “a space for the novel within a newly crowded commercial field” (9). To create such space, the industry marketed the novel “to an increasingly educated audience” as a commodity that “transcends commerce” (13). In isolation, this idea is unsurprising. Describing midcentury writers as “producers in a producer-oriented trade,” Brier’s insight is to demonstrate how they also “participated within their novels in the promotion of the novel in general as a cultural and political good, often in terms that echoed the industry’s promotional campaign and the rhetoric of culture critics” (15, emphasis in original).

Brier’s book concentrates on five novelists, but his method seems capable of wrestling with Bellow, whose work could also be said to “[celebrate] … the writer’s solitariness … against a corrupt, decadent, or totalitarian mass culture” (16).5 To bridge the gap between Bellow’s work and biography, this method could also build on Ohmann’s influential 1983 essay “The Shaping of a Canon: U. S. Fiction, 1960-1975.” In light of Brier’s scholarship, Ohmann’s argument can be read to suggest that “precanonical” American novels—his discussion includes Henderson, Herzog, and Humboldt’s Gift— satisfy the book trade’s twin mandates of literary value and cultural criticism by striking a particular relationship between style and narrative (208). For Ohmann, the stories are almost uniformly “narratives of illness” in which new-class protagonists endure alienation in confronting the supposed sickness of mass society and culture (217).6 Although their stories may “look very similar,” these novels are actually staking their strongest claims for their literary and political value through the mechanism of authorial style, or “the pursuit of a unique and personal voice” (209). And this idea of an inimitable style, as we have seen, is legible as an example of either Bellow’s new-class public service (Schryer) or his soul (the Companion editors). The more onerous task is connecting such style to Bellow’s relationship with his publishers. On first glance, Bellow does appear to view Viking Press in much the same way that readers regarded novels. More than just a commercial business, his longtime publisher was an Arnoldian collaborator in his supposedly lonely struggle.7 Indeed, Bellow’s letters express “love” for Viking; the press enables his style by recognizing his “pride as a workman” and by refusing to view his fiction through the eyes of a “canning concern,” a phrase evocative of the mass culture industries.8

Admittedly, the editors of Companion might view this approach with reservations since it implies that Bellow’s vocation motivates political beliefs—formal, cultural, or otherwise—that do not necessarily speak to the so-called perennial concerns of the American political condition. Nevertheless, I think that this approach shows how Bellow’s work can continue to teach us about, as Trepanier and Cronin put it, “the concrete and the complexity of life” (7).

endnotes:

1. Deneen complements this claim with a methodological one by promising that the essayists will “approach the classic texts not with a ‘hermeneutics of suspicion’”—the ubiquitous, corrosive tool of the left-of-center intellectual—“but with the curiosity of fellow citizens who believe that the great authors have something of value to teach their readers” (vii). But insofar as the phrase “hermeneutics of suspicion” describes a methodology, Deneen’s claim is overstated. Essays in this volume uncover the repressed histories of slavery, the Holocaust, the Vietnam War, and feminism “peek[ing] through the pages,” as one contributor puts it, of Bellow’s fiction (61).

Back to essay

2. Schryer, Fantasies of the New Class: Ideologies of Professionalism in Post-World War II American Fiction (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), 2.

Back to essay

3. Bellow, Mr. Sammler’s Planet (New York: Viking Press, 1970), 42.

Back to essay

4. Ohmann makes the connection between Bellow’s quotation and studies of reading. See Ohmann, “The Shaping of a Canon: U. S. Fiction, 1960-1975,” Critical Inquiry 10, no. 1 (Sep. 1983): 201.

Back to the essay

5. Evan Brier’s A Novel Marketplace: Mass Culture, the Book Trade, and Postwar American Fiction (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010) has chapters focusing on Paul Bowles, Norman Mailer, Grace Metalious, Sloan Wilson, and Ray Bradbury.

Back to the essay

6. It should be noted that Ohmann does not use the phrase “new class,” but instead refers to Barbara and John Ehrenreich’s description of a “Professional-Managerial Class,” or PMC (209).

Back to the essay

7. Founded in 1925 by Harold K. Guinzburg and George S. Oppenheimer, Viking Press incorporated hostility towards mass culture in its premise: to publish “distinguished fiction with some claim to permanent importance rather than ephemeral popular interest.”

Back to the essay

8. See Saul Bellow’s letter in James Atlas, Bellow: A Biography (New York: Random House, 2000), 225.

Back to the essay

cover art by Zoran Tucić

__________

Ben Rogerson is a Ph. D student in the Department of English at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. He is currently working on a book project that examines critiques of white-collar work in mid-twentieth century American film, fiction, poetry, and photography.