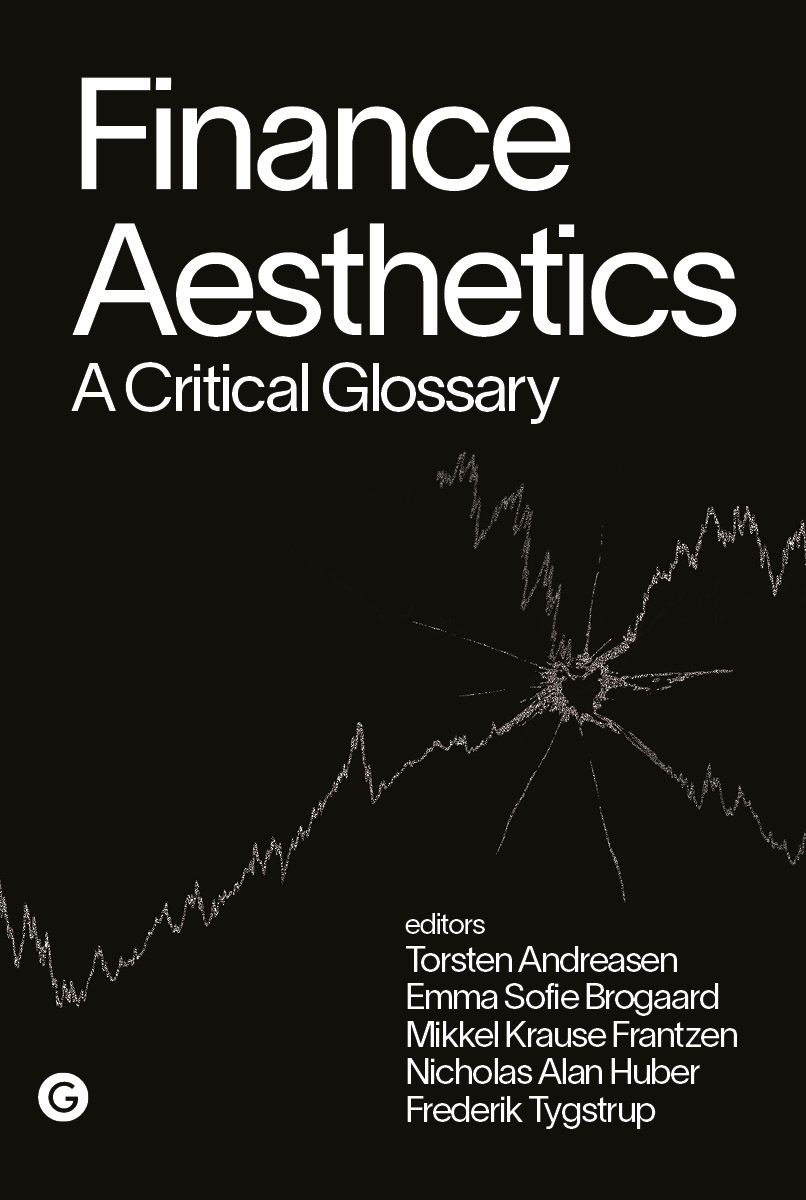

This article was published as part of the b2o review‘s “Finance and Fiction” dossier.

The Day the Music Died: Finance Fiction and the Affects of the Long Downturn

Torsten Andreasen

All About that Base…

Since the late 20th century, finance fiction has evolved through distinct affective phases – euphoria, schizophrenia, and resignation – both reflecting economic transformations and shaping the cultural logic of financialized capitalism. By bringing Robert Brenner’s theory of the long downturn into dialogue with Fredric Jameson’s waning affect, this article proposes a periodization of finance fiction that traces how affect mediates the contradictions of financial accumulation, not only registering crises in capitalism but also framing the ideological terms in which they are understood.

Robert Brenner’s theory of a “long downturn” in advanced capitalist economies since 1973 and Fredric Jameson’s description of the same period as a “waning of affect” have each inspired innumerable analyses and diagnoses of late capitalist society and its cultural artefacts[1]. The theory of the long downturn grapples with enduring low industrial profit rates due to persistent overcapacity despite decreased investment in labor and equipment (Brenner 2006). The waning of affect is characteristic of postmodernism as the superstructure correlate to the base of financialized economy’s compensation for waning industrial growth (Jameson 1991: xx-xxii): the transition from Munch’s Scream to Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe, from depth hermeneutics to simulacral surface, from a psychic experience and cultural language dominated by historical temporality to a fragmented hyper-spatiality transcending the modernist alienation of subjective anxiety and thus surpassing the capacities of the human sensorium and mutating the now ungraspable totality of the world system into impersonal schizophrenic experience.[2]

Brenner’s long downturn and the financial bubbles and busts obfuscating it, have been analyzed and debated in minute historical detail, while Jameson’s waning of affect has been an important reference for discussion of both other affects and other kinds of waning—for example, the waning of genre. However, it is much less frequent for the two to be considered together.

In an attempt to think through certain shifts in the historical development of cinematic and literary finance fiction, this article scrutinizes and further periodizes the waning of affect as a historical claim. It does so by considering affect in light of the long downturn, as specific affective reactions to concrete historical operations of financial capital after the post-war boom.

The concept of affect is often employed in a somewhat vague manner. Jameson considers affect to be the interior feelings or emotional states of a historically specific subject: the bourgeois ego. Since postmodernity entails the fragmentation of the subject, there is no longer any ego to contain the emotions of old, and instead of feelings and emotions, the postmodern subject is left with free-floating and impersonal intensities.

Holding on to Jameson’s notion of affect, I also consider a further, although more general, tradition of questioning affect: From Plato and Aristotle to Brian Massumi’s reading of Gilles Deleuze’s reading of Spinoza, the question of affect has been framed as the ability to “affect and be affected”. In Plato and Aristotle, the ability (δύναμις) to affect (ποιεῖν) and be affected (παθεῖν) is a fundamental “property of being” (ἴδιον τοῦ ὄντος) (Aristotle 1960: V, IX) or of that which has “real existence” (πᾶν τοῦτο ὄντως εἶναι) (Plato 1921: 247 d7-23). Focusing on human existence, Spinoza was in search of “that which so disposes the human body that it can be affected in many ways (ut pluribus modis possit affici), or which renders it capable of affecting external bodies in many ways (ad corpora externa pluribus modis afficiendum)” (Spinoza 2005: IV, prop. 38). Human affect, then, can be considered not so much a question of subjective or even impersonal emotion but as the ability to perceive, comprehend and react to the surrounding world: it is emotion as linked to perception, cognition, and, most importantly, agency.

Jameson’s periodizing analysis of the waning of affect as characteristic of postmodernity reminds us that although there exists a long and varied philosophical tradition of analyzing as “affect” the ability to affect and be affected, it should not simply be read as a transhistorical subjective category, where each encounter is one of either joy or tristesse. Affect relies on historically specific material conditions, and Jameson’s argument implies that in this stage of late capitalism, the joy or tristesse of Spinoza’s encounter are displaced by euphoria and schizophrenia.

Jameson himself defined the “ideological task” of the concept of postmodernism by referencing Raymond Williams’s concept of “structures of feeling” which, according to Williams, defines “forms and conventions in art and literature as inalienable elements of a social material process” (1977: 133) and describes how these structures constitute emergent, dominant, or residual social forms. I thus take affect to be a historically specific subjective ability to experience, feel, understand, and act within a given social material process – an ability enabled and mapped by cultural representation.

My question is, then, whether it would be possible to consider the waning of affect as discontinuous constellations of shifting cultural dominants and their accompanying residual and emergent forms in late capitalism. I tentatively answer this question by looking at the representation of financialized affect in a selection of films and novels ostensibly about finance to distinguish various affective modes in the cultural depiction of the financier subject.[3]

Jameson claimed that anxiety and alienation had been replaced by schizophrenia and euphoria as the two intensities available to the postmodern subject. I argue that within the cultural representation of the financier, euphoria and schizophrenia are historically separate modes, the second following the first, and both followed by a third. I thus propose to further periodize the conjecture of “waning affect” by sketching out three successive modes of perceiving, understanding, and reacting to one’s surroundings as they appear in finance fiction:

- “The Future’s So Bright, I Gotta Wear Shades”: euphoric hubris of the 1980s.

- “And as Things Fell Apart…”: schizophrenic horror of the 1990s and early aughts.

- “The Day the Music Died”: predominant resignation after the financial crisis of 2007-2008.

Through this periodization, I hope to analyze the cultural logic of financialized late capitalism as manifested in fictional renditions of finance in novels and movies.

The Future’s So Bright, I Gotta Wear Shades

The financialized economy that superseded the production-based economic expansion of the postwar boom is, in Marxian terms, based on the belief that it is possible to cut out commodity production from the general formula for capital, M – C – M’, so that money is exchanged for more money with no value-adding labor required. The formula for this is M – M’, what Marx called the “most superficial and fetishized form” (Marx 1981: 515) of the capital relation, it is “fictitious capital” (1981: Chapter 25).

The financiers in 1980s fiction all seem to subscribe to such a fantasy. Historically, this specific version of that recurring fantasy came out of the general slowdown in manufacturing profitability in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The slowdown was combatted by government facilitated debt creation – public, corporate, and private. Because of low profit rates, firms were unable to meet debt-fueled increases in demand by investing in production, and without an increase in supply prices went up (Brenner 2006: 157-159). The subsequent inflation peaked at 14.8% in March 1980, which was combatted by Fed Chair Paul Volcker by increasing the Fed funds rate to its peak of 20% in June 1981. The shift from Keynesian stimulus in the 1970s to Volcker’s monetarism at the end of the decade brought an abrupt end to subsidized demand and recession inevitably ensued.

Wall Street had suffered during this slowdown in production, and “Between 1968 and 1975 over 150 firms were absorbed or closed” (Bruck 1988: 29). But while Volcker’s decision to fix money supply and let interest rates float inaugurated a recession in the American economy from 1979-1982, it also marked what Michael Lewis called “the beginning of the golden age of the bond man” (Lewis 1989: 43). This period saw the invention of the securitized mortgage loan and its repackaging in the so-called Collateralized Debt Obligations and “between 1977 and 1986, the holdings of mortgage bonds held by American Savings and Loans grew from 12.6 billion dollars to 150 billion dollars” (142), i.e., more than a ten-fold increase over the course of a decade.

The early eighties also saw an explosion in Junk bonds (bonds rated below investment grade, i.e., BB+ or below) and the related debt-fueled hostile mergers and acquisitions which enabled the emergence of that crucial figure of the age: the corporate raider. This explosion in debt also drove stocks toward new highs before the crash in October 1987. The specific version of the fantasy of M – M’ which constitutes the clear cultural dominant of 1980s finance fiction should no doubt be seen in the light of this bull market run-up to the crash.

This first stage of my proposed periodization, the stage of euphoric hubris where the future is so bright that shades are strictly necessary, is the age of what has been called the “Masters of the Universe.” The financial masters were famously described in Tom Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities (1987) as the proud moniker which the protagonist, Sherman McCoy, awards himself:

[…] one fine day, in a fit of euphoria, after he had picked up the telephone and taken an order for zero-coupon bonds that had brought him a 50,000$ commission, just like that, this very phrase had bubbled up into his brain. On Wall Street he and a few others – how many? – three hundred, four hundred, five hundred? – had become precisely that… Masters of the Universe. There was… no limit whatsoever! (Wolfe 1987: 11)

These masters were also known as Big Swinging Dicks, as famously documented in Michael Lewis’s Liar’s Poker: “If he could make millions of dollars come out of those phones, he became that most revered of all species: a Big Swinging Dick” (Lewis 1989: 56). Limitless accumulation of capital through the technologically mediated and thus seemingly immediate exchange of paper: this is the fantasy of the masters of the universe. In terms of affect, Jameson’s euphoria is clear, even explicit. The ability of the financier to immediately affect the world renders the M – M’ relation sensible as the absence of material limits. Money is transformed into more money, just like that!

However, confronted with the stratified realms of production – the white working class (e.g., the airplane builders in Wall Street (1987) and ship builders in Pretty Woman (1990)) and racialized precarious labor (e.g., Eddie Murphy’s character Billy Ray Valentine in Trading Places (1983) and the depictions of Harlem and the Bronx in Bonfire) – these masters are generally depicted as incorporations of hubris. They are figures of Icarus who, in their euphoria, fly too close to the sun and fall as a result of their moral transgressions.

The immediate expansion of finance capital via M – M’ as cultural dominant is accompanied by the residual forms of the manufacturing sector, presented as the sound but betrayed foundation of the American economy. The machine maintenance workers of Bluestar Airlines in Oliver Stone’s Wall Street are the salt of the earth betrayed by the soaring immoral greed of Gordon Gekko and his protégé Bud Fox. When Bud’s analyses of publicly available stock data find little demand in his one-shot ideas pitch to Gekko, he proposes the airline in which his father is a machinist and union representative. His insider’s knowledge of the company’s troubled financial situation enables him to argue that there is money to be made if the unions agree to a 20% salary cut to be reversed if the company turns a profit. Gekko pretends to go along but in fact intends to break up the company, sell the parts, and siphon off the surplus in the pension fund.

As has been pointed out by Leigh Claire La Berge (La Berge 2015: 99), Bud is caught between his two fathers, the two ideals: on the one hand, the corporate raider for whom “Greed is good” and who clearly states “I create nothing; I own” and, on the other, the honest hard-working man who advises his son to “stop trading for the quick buck and go produce something with your life, create, don’t live off the buying and selling of others…”

The two confronting ideals are narratively deployed to organize a moral showdown between labor and predatory ownership, between “the real economy” and “fictitious capital”, between a post-war production economy and the financial “zero sum game” where “Money itself isn’t lost or made, it’s simply transferred from one perception to another. Like magic. […] The illusion has become real”, as Gekko puts it.

Wall Street and other finance fiction of the 1980s condemn finance in moral terms: the immorality of finance is to claim the reality of financial illusion, a claim rendered dubious in the film’s staging of the ideological confrontation between Gekko and Fox. During their heated exchange, the camera swivels restlessly around the two interlocutors, almost desperately avoiding a steady shot. But exactly at the transition from Gekko’s “I create nothing” to “I own”, the camera finally rests on Gekko in a satisfied pose, drink in hand, and New York skyscrapers as a backdrop. That brief image of capital’s self-satisfaction is only disturbed by the worker on a lift outside the building, cleaning the windows with long strokes from top to bottom.

Gekko’s demonstrative pose as master of the universe is only minimally tainted by the slow movement of manual labor. I disagree, here, with La Berge’s description of the window cleaner as an evocation of “cleansing” (110). I would argue, rather, that he is an almost comical stain on the fantasy of frictionless transition of money from illusion to reality. Even in the most glorious image of the dominance of finance capital, the residual head of manual labor pops into the frame and by the strokes of its servicing hands discretely insists on labor as the inescapable material reality behind financial euphoria.

A similar confrontation between the dominant fantasy of financial profit without cumbersome labor and the residual postwar ethos of a production-driven economic expansion appears in Pretty Woman where the corporate raider Edward Lewis is brought onto a more virtuous path by a sex worker with a heart of gold. The movie presents several forms of labor: the sex work of Vivian and her friend Kit, the corporate raiding of Edward and his icky lawyer Stucky, the service work of the hotel manager Barnard, the Rodeo Drive saleswomen, other service workers, and, finally, the family founders of the shipbuilding Morse Industries.

Although the movie hints at the troubles of sex work by briefly mentioning the death of Skinny Marie (who Kit repeatedly dismisses as a flake and a crack head who is thus not worthy of Vivian’s “Cinder-fucking-ella”-like social ascent), the material conditions that constitute such work are quickly occluded by the question of inner subjective nobility predetermining social destiny. Because Vivian flosses her teeth and weeps with emotion at the opera, she proves a true princess who should, surely, be rewarded with a true prince protruding from a limousine sunroof, that preferred steed of budding financial royalty.

Pretty Woman’s particular rendition of several age-old narrative schemata (e.g., Cinderella and Pygmalion) gets historically specific, however, when depicting the two mutually constitutive transformations in Vivian and Edward. In the opening scene, midway upon the journey of his life, Edward finds himself without a straightforward pathway. Lost in a Lotus, descending into the inferno of Hollywood Boulevard, Edward encounters real-world wisdom and grace united in the form of Vivian. The financier in the penthouse suite whose vertigo announces his inability to confront the material conditions of his social status is brought out of the euphoric hubris of his station by the straightforward humanity and nobility of the sex worker. The nobility of physical labor enables him to realize the ignominy of the M – M’ fantasy. As he says to Stucky: “We don’t build anything, Phil. We don’t make anything.”

Instead of buying Morse Enterprises to break the company apart and sell the pieces in a replica of Gekko’s plan for Bluestar, Edward decides to invest in the company’s production: “Mr. Lewis and I are going to build ships together. Great big ships” as Mr. Morse says, thus providing Edward with a new and more benevolent father of industrial production than the one of inherited wealth who divorced his music teacher mother and thereby drove Edward towards the immoral quest of corporate raiding – a quest initiated by taking over and splitting up his father’s company in a fit of oedipal frenzy.[4]

While Edward is obviously the knight in suit and shining armor, Stucky is the villain, insisting on maximizing profits through corporate raiding and even venting his frustrations with Edward’s newfound nobility by violating its source, Vivian, who, as a sex worker, is supposedly obliged to obey the proposition of an impromptu stint of wage labor. But the villainy of Stucky is the very condition of possibility of Edward’s nobility, just as Vivian’s nobility rests on the backdrop of a dead Skinny Marie. Only because the raw greed and dirty business tricks have been outsourced to Stucky – “That’s why I hired you, Phil, to do my worrying for me” – can Edward maintain the shine of his armor, and only because of the crackhead flakyness of certain colleagues can Vivian’s nobility stand out enough for her to ascend beyond her station and, from there, engage in the benevolent financing of Kit’s education. Carved of less noble wood than Vivian, Kit needs a philanthropic push from those of natural worth to work her way towards middle class respectability while Vivian takes the express elevator straight to the penthouse.

The problem with this plot where innate moral nobility redirects the dominant 1980s fantasy of M – M’ back towards the residual M – C – M’ of a supposedly healthy and noble postwar industrial economy, is that such a turn enacts an ideological intervention in the historical causality of capital. Contrary to the movie’s claims, a return to an earlier era of production is not a question of morals. The laws of capital demand profit and you can neither morally nor magically restore the profitability of the manufacturing sector.

The residual aspect of Pretty Woman does not solely spring from its fairy tale plot, then, but from the persistence of a postwar ethos of production as a valid response to the beginning cracks in the 1980s fantasy of finance, cracks that became exceedingly manifest on October 19, 1987, the day of the so-called Black Monday stock crash. The depiction of finance as moral corruption is a very real “imaginary resolution of […] objective contradictions” (Jameson 1981: 118). Pretty Woman and its contemporaries thus provide a residual affective response to the failing affective dominant of the 1980s. It is not simply a nostalgia for the good old days, but the claim that only the immorality of a few Gekko’s and Stucky’s inhibit the restoration of the supposedly more sustainable and more noble character of production and honest labor. The failure of this residual affect of the post-war boom to actually and not just imaginarily resolve the failing affect of euphoria becomes the main problem in my two subsequent periods.

And as Things Fell Apart…

Something emerged in the cultural representations of finance in the beginning of the 1990s. A new threat of a schizophrenic disintegration of signifying surfaces seems to accompany a shift in the cultural perception of the financial sector after the Black Monday stock crash on October 19, 1987. The bull market of 1981-1987 came abruptly to a halt, and what could, in relation to the crash, be considered the euphoric hubris of Wall Street traders bound to fail and fall soon turned out to be a systemic negation of reality.

Along with the authorities in other countries, e.g., Japan, the US Fed decided to alleviate the collapse in equity prices by cutting interest rates. Volcker’s successor as chairman of the Fed, Alan Greenspan, slashed short term interest rates to zero between 1990 and 1993 to help the market and it was widely believed that, as Robert Brenner’s critical account of this time would have it, “the stock market would never be allowed to drop too severely, and the bull run continued” (Brenner 2000: 16). Nobel Prize-winning economist Rudiger Dornbusch expressed the belief clearly in 1998: “This expansion will run forever” (Dornbusch 1998). Brenner more pertinently described the asset-price run-up in the late 1990s as a stock market “climbing skyward without a ladder” (Brenner 2009: 21).

Further, the recession of 2000-2002, i.e. the bursting of the dot.com-bubble, was quickly followed by yet another ladder-less climb, this time in bonds. Driven by an initially low interest rate and the explosion of subprime loans, another bubble violently separating the financial sector from its material underpinnings was underway and about to finally burst both the euphoric fantasy of the 1980s and its haunted schizophrenic counterpart in the 1990s and early aughts.

The year after Pretty Woman attempted to save financial capital from euphoric hubris by insisting on the possibility of profitable investment in manufacturing, Brett Easton Ellis’ American Psycho (1991) introduced a new cultural response to the market’s systemic negation of reality by exhibiting the collapse of fantasy into horror. As a chapter title announces, the novel stages the “End of the 1980s”. With the rambling confessions of the investment banker Patrick Bateman – the next generation financier, who is neither a new Master of the Universe “with a taste for human flesh”, as one commentator would have it[5], nor much of a master at all – we have gone from the dominant hubris of 1980s financial euphoria accompanied by industrial production as its residual moral counterpart to the dominant schizophrenic dissolution of the financier subject: “my depersonalization was so intense … I was simply imitating reality, a rough resemblance of a human being …” (Ellis 1992: 282).

In American Psycho, euphoric hubris joins the remnants of the industrial expansion as the residual affective forms accompanying dominant schizophrenic horror. The fantasy of a world of financial signs with immense exchange value but very little material reality behind them to limit their instantaneous circulation has begun to crack and fragment its correlated subjective form: “There wasn’t a clear, identifiable emotion within me, except for greed and, possibly, total disgust” (282).

These schizophrenic intensities of the pleasure principle with no reality in sight are manifested in the main formal characteristic of American Psycho which is repetition standing in for plot: The enumeration of brands, the more or less heated arguments about table reservations, the inability of anyone to recognize anyone else, the renting and returning of video tapes, the frantic and senseless cash withdrawals from ATMs, and, of course, the forced iterations of physical violence desperately exploring new extremes to escape the dullness of the very repetitions to which they contribute.

The bourgeois ego that reached its limit in the greed of Gekko and Stucky but retained a certain affective capacity for shame or remorse in Bud Fox, Sherman McCoy, and Edward Lewis, has now fallen apart and been reduced to a narrative structure with “… no catharsis. I gain no deeper knowledge about myself, no new understanding can be extracted from my telling. There has been no reason for me to tell you any of this. This confession has meant nothing” (388).

Nothing is to be learned, nothing to be gained, and the bizarre, automated telling machine convincingly described by La Berge (2014: 133-138) has no point but its own continuation: “I just want to… […] keep the game going” (Ellis 1992: 394). The Automated Telling Machine seems to be a ploy to render the reader just as empty and numb as its narrator: “expecting a heart, but there is nothing there, not even a beat” (116). The listing of brand names and consumables almost challenges the reader to not skim or skip ahead, just as the violence constantly probes whether the reader maintains the ability to be affected. The purpose of this, of course, is the interpellation of any unaffected reader as the hypocritical semblable of the narrator.

La Berge argues that “American Psycho destroys the very genre that it creates” (La Berge 2014: 113). If genre, as Lauren Berlant would have it, provides “an affective expectation of the experience of watching something unfold” (Berlant 2011: 6), the novel’s destruction of genre consists in the extensive use of repetition in lieu of plot to numb the reader’s sensorium so that, indeed, no hope of unfolding is possible for those who enter. Joshua Clover observes: “Narrative requires motion and change, not simple replenishment; motion and change are exactly what constitute the general formula [of capital]. Implied in M-C-M’ … is not simply change and motion but expansion beyond any limit …” (Clover 2011: 36). For Bateman, there is no possible catharsis, no possible development or systemic expansion, just the eternal continuation of the same game.

That plot development and economic expansion are both residual expectations haunting the dominant psychosis of a 1990s and early aughts bull markets with extremely distant material underpinnings is not just characteristic of American Psycho but can be read as part of a wider tendency. While the big swinging dicks of the eighties tried and failed to master the universe – they flew too close to the sun and got burnt – Bateman’s generation is frantically trying to navigate the financial imaginary in a world of signs increasingly haunted by their negated material referent.[6] Bateman’s killing spree is an attempt to break out of this postmodern Platonic cave, not to touch the sun but to reach the sunlight of actual reality.

If American Psycho is the first clear manifestation of this period of schizophrenic affect, Don DeLillo’s Cosmopolis (2003) can be read as its culmination. While American Psycho was an explicit step beyond Bonfire, Cosmopolis is, in many ways, a clear continuation of American Psycho. After having his Rolex stolen at gunpoint as revenge for one of his murders, and he sobbingly expresses his humble desire to “keep the game going”, Bateman is presented with an injunction: “As I stand, frozen in position, an old woman emerges behind a Threepenny Opera poster at a deserted bus stop and she’s homeless and begging, hobbling over, her face covered with sores that look like bugs, holding out a shaking red hand. “Oh will you please go away?” I sigh. She tells me to get a haircut” (Ellis 1991: 394).

Along with an inexplicably mounting yen, this task provides the central plot device in Cosmopolis.

The financier Eric Packer rides around in his limousine manifestation of the Big Swinging Dick fantasy of an immaterial connection to the market and the future as such: pure M – M’. The limousine is, however, also the vehicle bringing him to the goal of the day: a haircut – a financial term meaning the reduction in a given asset’s value, as compared to market value, when it is used as collateral for a loan. But in this case, Packer literally wants a haircut from his old family barber, Anthony, who knew his father and gave him his very first haircut. Of course, Packer is unable to go through with this emotional confrontation with his past and leaves in the middle of the haircut.

Here, the limousine is far from Edward’s princely steed in Pretty Woman. It is now the postmodern Platonic cave on wheels, an immaterial fantasy connected to material reality via screens and data.

Material and emotional reality is the weak residual expectation or goal haunting the fantasy of high finance. Through the limousine sunroof, Packer contemplates an urban scene, focusing on the bank towers a bit further away: “They were the end of the outside world. They weren’t here, exactly. They were in the future, a time beyond geography and touchable money and the people who stack and count it” (DeLillo 2003: 36). They are so abstract that he must concentrate to see them. The material world becomes the disturbing veil through which to glimpse the abstraction of something purer. But the abstraction of the “pure spectacle, or information made sacred, ritually unreadable” (80) holds its own haunting. Not just the difficulty of focusing on the abstraction of information through the materiality of the bank towers, but also the inability of the abstraction of the market to encompass concrete life and death: “People will not die … People will be absorbed in streams of information” (104). But when confronted with the televised images of a man in flames, reality beyond financial signifiers crack the surface of the spectacle of the market: “The market was not total. It could not claim this man or assimilate his act. Not such starkness and horror. This was a thing outside its reach” (99-100).

Packer’s asymmetrical prostate is the subjective, physiological counterpart of what cannot be assimilated by data and should therefore, according to his doctor, be allowed to “express itself”. This becomes the ethos of a financier staring at the impossible soaring of the yen on which his fortune depends. This subjective expression of objective contradictions – in this case the soaring yen as well as generalized misery and numerous deaths (real, fake, and threatened) – plays out in a realm of surfaces with no material backing. Like American Psycho, this is formally manifested through repetition: Finance requires a new theory of time to understand the repeated temporal glitches of the limousine security camera and television screens, where the mediated events often precede their actual occurrence; Packer has multiple chance encounters with and misrecognitions of his wife, recalling the misrecognitions in America Psycho; the semiotic construction of reality is explicitly questioned by the repeated claims of the referential obsolescence of words, objects, and subjects.

This problem of referentiality comes down to what Packer’s Chief of Theory terms “an aesthetics of interaction” (86) charting what Packer describes as a “… common surface, an affinity between market movements and the natural world” (86). This is the affinity that no longer applies. The yen soars skyward without a ladder and things no longer chart. The “new and fluid reality” (83) of cyber-capital is money “talking to itself” (77) and “lines of code that interact in simulated space” (124). And the subject desiring a realm of pure information excluding subjective agency, this self-contradiction, finally expresses itself in a longing for action[7]: “He was alert, eager for action, for resolution. Something had to happen soon, a dispelling of doubt and the emergence of some design, the subject’s plan of action, visible and distinct” (171-172). A subject’s plan of action which in this period leads only to death, but which, soon, will lead nowhere.

The Day the Music Died

In the 1980s, dominant euphoric hubris was accompanied by a residual belief in the continued viability of an industrial economic expansion. The resulting moral indictment of financial fantasy – the belief in production as the true driver of economic expansion itself becoming a driver of narrative development – however, soon disintegrated into the formal repetitions of schizophrenic horror during the 1990s and early aughts. Those formal repetitions were haunted by the failure of the residual expectations of plot development and economic expansion, no longer present to restore the balance and bring Icarus to justice. The falls of Icarus – first, from the penthouse to jail and, next, the quest for reality disintegrating into death – were both historically separate versions of “the feeling of M – M’, haunted by the C to come” (Clover 2011: 46). In the 1980s, the fantasy of M – M’ was haunted by the crisis of profitability in manufacturing, i.e. in the sphere of production, while, in the subsequent period, it was haunted by the circulation and consumption of commodities as empty signifiers and immaterial data. In my final period, post-crisis resignation can be described as the affective correlate of the reassertion of the economic law of value: “The law of value asserted itself with savage clarity, fictitious capital was destroyed, jobs were annihilated, exported immiseration refluxing toward the economic cores” (Clover 2012b: 113). As the profits of a hoped-for future production proved absent, the temporal fix collapsed in an instant and the spatial fix returned only misery.

There is a vast archive of narrative fiction representing the resignation of the post-crisis financier and questioning the narrative structuring of the financial economy through plot: Sebastian Faulks’ A Week in December (2009), Jonathan Dee’s The Privileges (2010), Adam Haslett’s Union Atlantic (2010), Justin Cartwright’s Other People’s Money (2011), John Lanchester’s Capital (2012), Zia Haider Rahman’s In the Light of What We Know (2014), Adam McKay’s movie The Big Short (2015), Paul Murray’s The Mark and the Void (2015), and Gary Shteyngart’s Lake Success (2018) all stage financiers, nostalgically longing for lived reality, and a financial profession no longer understanding what it is doing or why it is doing it.

Murderous horror in the quest for reality has been replaced by the longing for simple things like childhood memories, romance without consideration for social status, a sense of control of one’s destiny, a sense of nation, a sense of family… It is the hope to be delivered from abstraction while resigning to the acknowledgement that reality is not readily available. The hubris of finance remains as a residual affect but without the euphoria, i.e., only in the form of explicit renunciation of sensible reality and emotional ties in favor of a focus on the numbers and the ensuing profit – without desire, horror, or haunting. The dominant affect is therefore, quite clearly, resignation.

In J. C. Chandor’s movie Margin Call (2011), Jeremy Irons’ diabolic CEO, John Tuld – a less than subtle reference to Lehman CEO Dick Fuld – clearly states the dominant affect: “I am here for one reason and one reason alone. I am here to guess what the music might do a week, a month, a year from now. That’s it, nothing more. Standing here tonight, I am afraid that I don’t hear a thing. Just silence.”

It is the day the music finally died. The movie opens with layoffs at a large investment bank. Leading risk analyst Eric Dale is fired but, just before leaving, he hands a yet to be resolved riddle to junior risk analyst Peter Sullivan. Peter cracks it and communicates the extreme danger of the company’s current overleveraged position to higher management. This opening establishes the “epistemological distance between the players and the rest of the world” (Clover 2012a: 8) where a couple of risk analysists and higher management alone know what the markets would inevitably soon learn in the form of the 2008 crash. This epistemological distance structures both the staged separation of those who know from those who do not and the plot’s development toward dumping toxic assets onto an unknowing market at the price of annihilating all trust between trading partners and thereby ending the trader’s professional futures.

The epistemological distance clearly operates as an aesthetic instrument. While scrutinizing the numbers, Peter is acoustically cut off from the surrounding office space by his earbuds and, visually, by the illuminated screen against the darkened offices. The city is present merely as indistinct lights beyond soundproof windows. Even when Peter and his fellow analyst Seth go out to retrieve Eric, the fired source of knowledge who is nowhere to be found, the passing urban scenery is perceived as vague and hazy shapes beyond the windows of a chauffeured car. Only after dawn, when they finally find Eric and the epistemological distance is about to vanish, the world becomes distinguishable when perceived from an open convertible.

In this narrative, as in this final phase of my periodization more generally, the fundamental opposition is not between financial cynicism and the production economy but, as pointed out by Clover, between the greedy cynicism of management and the morally pure calculations of the analysts. The “ideological payload” is “precisely the proposition that quantification is not itself a problem: quantification is on no one’s side; the risk is in its misuse” (8). The hunt for the lost risk analyst is explicitly a matter of information control, but it also obviously implies that the party could have continued were it not for a new kind of hubris: this time, not the renunciation of the “sound” production economy, but of the “sound” and risk-controlled mathematical foundation of the financial system.

Although pure mathematics is the new position from which to launch the moral indictment of financial greed – a greed incorporated by Tuld who shrugs at the repeated financial crises: “It’s all just the same thing over and over; we can’t help ourselves” – the residual affect of the production economy persists. When they finally locate Eric, he continues the tradition from Edward’s “We don’t build anything, Phil. We don’t make anything” in Pretty Woman and Gekko’s “I create nothing; I own” in Wall Street: “Do you know I built a bridge once? … I was an engineer by trade.” After a lengthy calculation, he concludes: “[t]hat one little bridge has saved the people of those communities a combined 1,531 years of their lives not wasted in a fucking car.” The affect of the production economy persists, though no longer as a salute to honest and noble industrialized labor but as a means to optimize the productivity of human capital. The difference between these two perspectives on “building” – the difference between Pretty Woman’s Edward and Margin Call’s Eric Dale – is the one expressed by the transformation of Dolly Parton’s canonical song “9 to 5” (1980) from a 1980s lament of poorly waged and little-credited office work to a post-crisis advertisement jingle, “5 to 9” (2021), about the realization of human capital as the goal and meaning of life.

The dominant cultural affect in Margin Call and, indeed the whole period, however, remains resignation. At the end of the movie, the traders are paid to destroy their future ability to trade ever again by dumping worthless assets, i.e., they cut their relations to the market, their ability to affect and be affected by it. The traders lose their relation to the market, while others keep that relation but lose their personal, emotional ties. Head of Sales and Trading, Sam Rogers, is finally kept on at the company, paid to ignore his moral disgust with his own complicity. In the beginning, while preparing a pep talk for his traders about to be laid off, he is in tears, not in solidarity with his employees, but at the news of his dog’s terminal illness. At the end, after the liquidation of toxic assets, the firing of the remaining employees, and the collapse of the epistemological distance under the general market crash, after accepting management’s money offer to ignore his own inclinations and keep the game going, we find him digging the dog’s grave in his garden – the sounds of the digging continuing into the end credits.

This is the end…

By pairing it with Brenner’s long downturn, Jameson’s waning of affect can thus, I argue, be further periodized as a number of emergent and residual forms interacting in finance fiction from the 1980s until today. The emergence of the master of the universe during the run-up to the 1987 crash carried with it a residual faith in the continued viability of the post-war industrial boom and the related moral indictment of fictitious capital’s promise of economic expansion without manufacturing and thus without a certain exploitative societal distribution of wealth through wage labor.

In the 1990s and early aughts, the residual affective structure of noble industrial labor and its moral condemnation of the dominant euphoric hubris gave way to on a dominant affect of schizophrenic horror, fragmenting the subject and the ability of language to index reality. The residual structure, here, seemed less the nobility of labor and commodity production to sustain M – C – M’ but the circulation and consumption of commodities as empty signs and dubious data, exchange value without use value. The music had seemingly lost its base. Where, in the 1980s, the financier tended to end up in jail, he now surrendered himself to death and destruction, the absence of exit from haunted existence forcing an eternal repetition of violence, both exuberant in its transgressions and desperate for its own end.

As the haunted system crashed spectacularly during the financial crisis of 2007-2008, resignation emerged as the new dominant affective mode. Whether giving up on the illusion of financial mastery to recover a sense of control by retreating to personal emotional bonds or by giving up on emotional contact altogether to sustain the residual fantasy of self-sufficient financial products, resignation has become unavoidable. ‘Your money or your life’ is, indeed, the fundamental ultimatum of post-crisis finance fiction.

In a certain way, the masters of the universe subscribed to Marx’s ironic description of money from 1844: “The extent of the power of money is the extent of my power. … Do not I, who thanks to money am capable of all that the human heart longs for, possess all human capacities?” (Marx 1970: 324). But the master financier only considered one side of the coin, as it were. Marx continued: “If money is the bond binding me to human life, binding society to me, … [i]s it not, therefore, also the universal agent of separation?” (324).

The schizophrenic experience springs from the beginning realization in the finance fiction of the 1990s and early aughts that the problem of finance is not reducible to the pursuit of money by immoral means but, rather, that “[m]oney is the alienated ability of mankind”, that money turns ability “into its contrary” and operates as the “distorting power against the individual and against the bonds of society …” which “confounds and confuses all things” (325). The meaningless repetitions and repeated meaningless violence constitute the attempt to either end or transcend a world that has revealed itself as “the fraternization of impossibilities” (325).

Post-crisis resignation, then, poses the question of the possibility for a financialized “relationship to the world to be a human one” (326). The financier either attempts to abandon the exchange of paper to “exchange love only for love, trust for trust, etc.” (326), or he abandons love and material reality in favor of the magical self-sufficient power of money. These two forms of resignation are not the first glimpse of a future after capital, however. What was in the 1990s the schizophrenic ambivalence – the search for the exit and hope for the game to continue – has now been separated as two distinct forms of resignation, two roads – your life or your money – both leading nowhere.

However, Marx’s analysis of money progressed from a question of the human relationship between subject and world – where the alienating mediation of money is vanquished by love, trust etc. evenly given and received – toward an analysis where money is an expression of value within capitalist social relations. Similarly, the analysis presented here of the varying degrees of universal mastery wielded by the financier subject should progress toward not simply other subjective forms than the financier – those excluded from the narrative or forced into the background on the basis of race, class, or gender as conditions of possibility for the affect of the financial agent – but toward a questioning of the insistence of finance fiction to engage with finance in terms of subjectivity, thus occluding the analysis of the impersonal structural violence operated by financial capitalism. The purpose of the analysis is therefore not just to propose a periodization of financial affect but to lay the groundwork for a further study of the ideological operations of finance fiction, which, by various imaginary resolutions of objective contradictions, tend to limit our critical scope. Immoral hubris, schizophrenic horror, or the resignation of lost illusions all partake in the same ideological claim: that the problem is caused by our errant subjective agencies within the world of capital and not by the capitalist mode of production as such. The different phases of waning affect within finance fiction are active responses to a failing fantasy, a fantasy that survives in residual forms to this day. I have tried to present the phases as historically specific affective relations to developments within capital accumulation, but the goal must be to go beyond the crises of subjective fantasy and seek an active response to the failing self-reproduction of capitalist social relations which, along with its fantasies, deserve to be laid to rest.

Torsten Andreasen’s work currently focuses on the periodization of the correlation between culture and financial capital since 1980.

Works cited

Aristotle. “Topica.” In Posterior Analytics. Topica. Translated by E. S. Forster, and Hugh Tredennick. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1960.

Arrighi, Giovanni. The Long Twentieth Century. London & New York: 1994.

Berlant, Lauren. Cruel Optimism. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011.

Brenner, Robert. “The Boom and the Bubble”. In New Left Review, no. 6 (Nov Dec 2000): 5-43).

Brenner, Robert. Economics of Global Turbulence – The Advanced Capitalist Economies from long Boom to long Downturn, 1945-2005. London & New York: Verso, 2006.

Brenner, Robert. “What Is Good for Goldman Sachs Is Good for America: The Origins of the Current Crisis,” April 2009, http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/issr/cstch/papers/BrennerCrisisTodayOctober2009.pdf.

Bruck, Connie. The Predators’ Ball: the Junk-Bond Raiders and the Man Who Staked Them. New York: The American Lawyer, 1988.

Cartwright, Justin. Other People’s Money. London: Bloomsbury, 2011.

Clover, Joshua. “Autumn of the System: Poetry and Financial Capital.” Journal of narrative theory 41, no. 1 (April 1, 2011): 34–52.

Clover, Joshua. “Playing by the numbers.” Film Quarterly, Vol. 65, No. 3 (Spring 2012a), pp. 7-9.

Clover, Joshua. “Value | Theory | Crisis.” PMLA 127, no. 1 (2012b): 107–114.

Clover, Joshua. “Crisis.” Pendakis, Andrew, Imre Szeman, and Jeff Diamanti (eds). The Bloomsbury Companion to Marx. London: Bloomsbury, 2018.

De Boever, Arne. Finance Fictions – Realism and Psychosis in a Time of Economic Crisis. New York: Fordham University Press, 2018.

Dee, Jonathan. The Privileges. New York: Random House, 2010.

DeLillo, Don. Cosmopolis. New York: Picador, 2003.

Dornbusch, Rudiger. “Growth Forever,” Wall Street Journal (30 July, 1998).

Ellis, Bret Easton. American Psycho. London: Picador, 1992.

Faulks, Sebastian. A Week in December. London: Hutchinson, 2009.

Harvey, David. The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change. Cambridge, Ma.: Blackwell, 1990.

Haslett, Adam. Union Atlantic. London: Tuskar Rock Press, 2010.

Jameson, Fredric. The Political Unconscious – Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1981.

Jameson, Fredric. “Postmodernism, Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism.” New Left Review, no. 146 (July-August, 1984): 59-92.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. London & New York: Verso, 1991.

Jameson, Fredric. “Culture and Finance Capital.” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 24, No. 1 (Autumn, 1997), pp. 246-265.

Jameson, Fredric. “The Aesthetics of Singularity.” New Left Review, 92 (March-April, 2015), pp. 101-132.

La Berge, Leigh Claire. Scandals and Abstraction: Financial Fiction of the Long 1980s. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Lanchester, John. Capital. London: Faber and Faber, 2012.

Lewis, Michael. Liar’s Poker. New York: Norton, 1989.

Mandel, Ernest. Late Capitalism. London & New York: Verso, 1978.

Marx, Karl. “The Power of Money” in Marx and Engels Collected Works, Volume 3, Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1970.

Marx, Karl. Capital vol 3. London: Penguin, 1981.

Murray, Paul. The Mark and the Void. London: Penguin, 2015. Apple Books.

McClanahan, Annie: Dead Pledges: Debt, Crisis, and Twenty-First-Century Culture. Stanford, Ca.: Stanford University Press, 2017.

Plato. “Sophist.” In Theaetetus. Sophist. Translated by Harold North Fowler. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1921.

Rahman, Zia Haider. In the Light of What We Know. London: Picador, 2014.

Spinoza, Baruch de. Ethics. Translated by Edwin Curley. New York: Penguin Classics, 2005.

Shteyngart, Gary. Lake Success. New York: Random House, 2018.

Williams, Raymond. Marxism and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Wolfe, Tom. The Bonfire of the Vanities. New York: Picador, 1987.

[1] Jameson bases his economic periodization of the waning of affect on Ernest Mandel’s Late Capitalism (1978). However, in later engagements with finance capital (Jameson 1997; 2015), he turns to Giovanni Arrighi’s The Long Twentieth Century (1994).

[2] See Jameson (1984) and (1991: chapter 1).

[3] This financier protagonist of finance fiction is predominantly white and male, a dominance only partially challenged in the last of the three phases that I intend to lay out. I hope to present a study of those occluded from the both economic and narrative universe of the financial masters in a later publication.

[4] It should be noted here, that both Wall Street and Pretty Woman associate what they consider the morally sound capitalism of industrial production with international transportation: airplanes and ships, the essential foundation for the “spatial fix” of globalization. David Harvey famously argued that the fading postwar boom sought a “spatial fix”, i.e., the inclusion of new and geographically dispersed markets and labor forces in the capitalist system. The spatial fix of globalization, however, required a further temporal fix in the form of financialization, defined as “capital that has a nominal money value and paper existence, but which at a given moment in time has no backing in terms of real productive activity or physical assets as collateral” (Harvey 1990: 182). As formulated by Annie McClanahan: “it allows capital to treat an anticipated realization of value as if it has already happened. … financialization allowed capitalism to supplement the declining profitability of investment in present production with money borrowed from the profits of a hoped-for future production” (McClanahan 2017: 13). By morally contrasting the means of international transportation and trade with the immorality of finance, the two films almost seem to propose that the spatial fix will be sufficient for sustainable economic expansion and that the “temporal fix” of finance is but immoral exuberance. That the spatial fix is necessarily linked to the colonial enterprise and war effort of empire is only hinted at by Morse Industries’ potential contract to build destroyers for the Navy.

[5] Quoted in (La Berge 2014: 130).

[6] A similar development can be seen in the use of Talking Heads songs in Wall Street and American Psycho, respectively. In Wall Street, the decoration of Bud Fox’s new apartment is accompanied by the Talking Heads song “This must be the place”, whereas American Psycho opens, as mentioned with “and as things fell apart / Nobody paid much attention” from the songs “Flowers” about the inability to live in a new paradise, where consumer society is covered in flowers. The last words of the song: “Don’t leave me stranded here / I can’t get used to this lifestyle.”

[7] Arne De Boever argues that “Packer, throughout the novel, seems to be in search of such threats and their potentially fatal consequences in a desperate attempt to encounter something – anything – real” (De Boever 2018: 2). The same applies to Bateman, though both characters also share a desire to perpetuate the game—one within the realm of simulacral surfaces, the other within pure information.

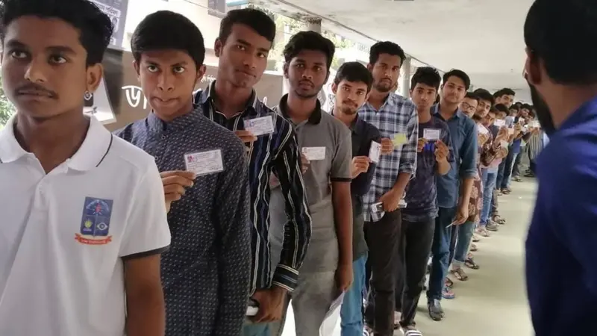

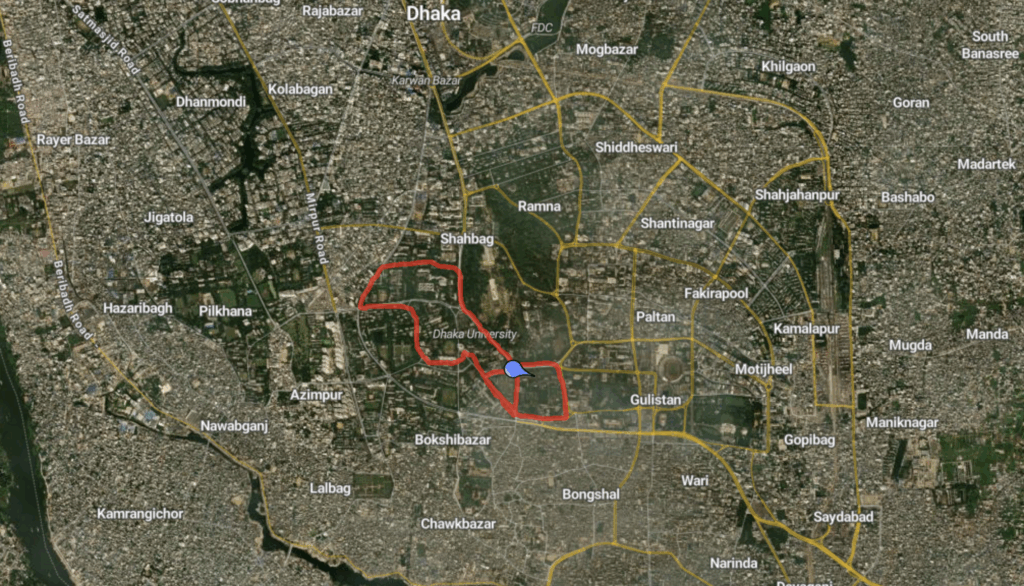

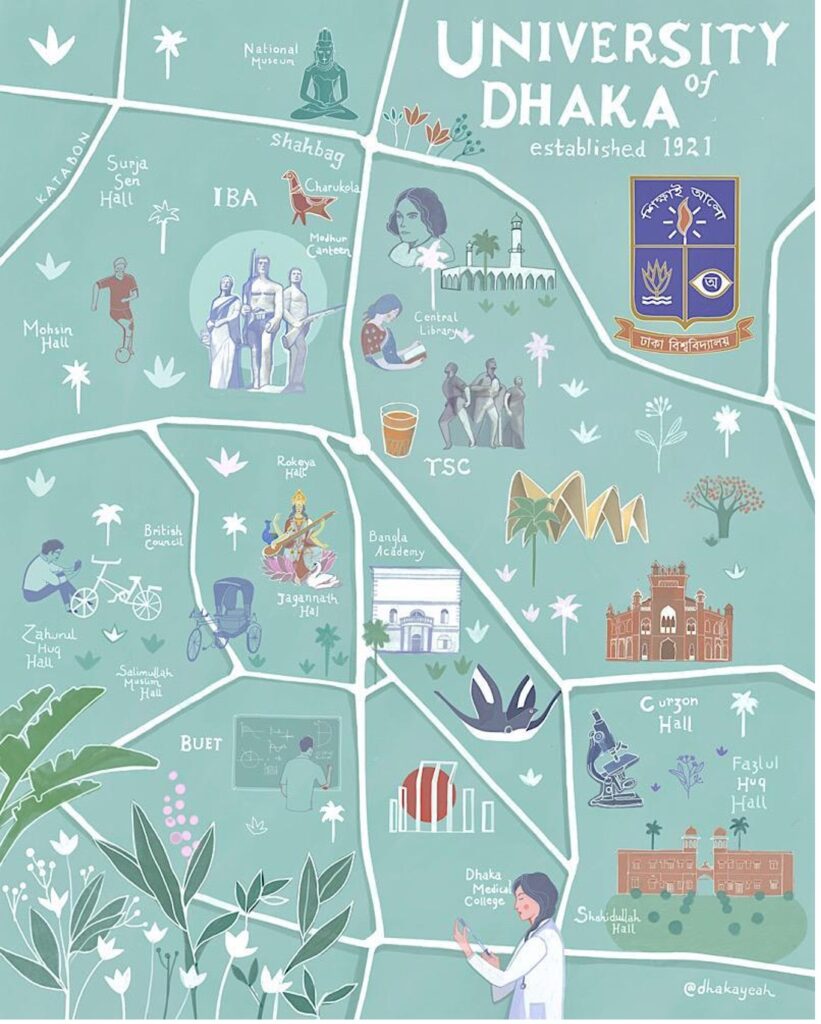

Figure 1: Dhaka University.

Figure 1: Dhaka University.  Map 1.

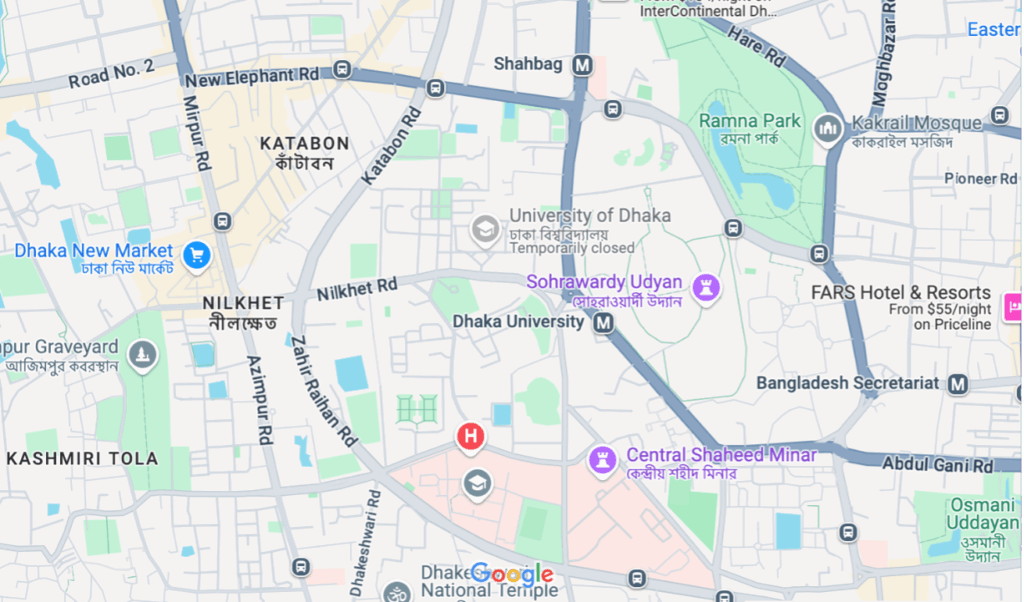

Map 1.  Map 2.

Map 2.

Figure 5, ©JagoNews24. Scenes from Shapla.

Figure 5, ©JagoNews24. Scenes from Shapla.  Figure 6, ©Syed Zakir Hossain.

Figure 6, ©Syed Zakir Hossain.

Figure 10, ©amarbarta.

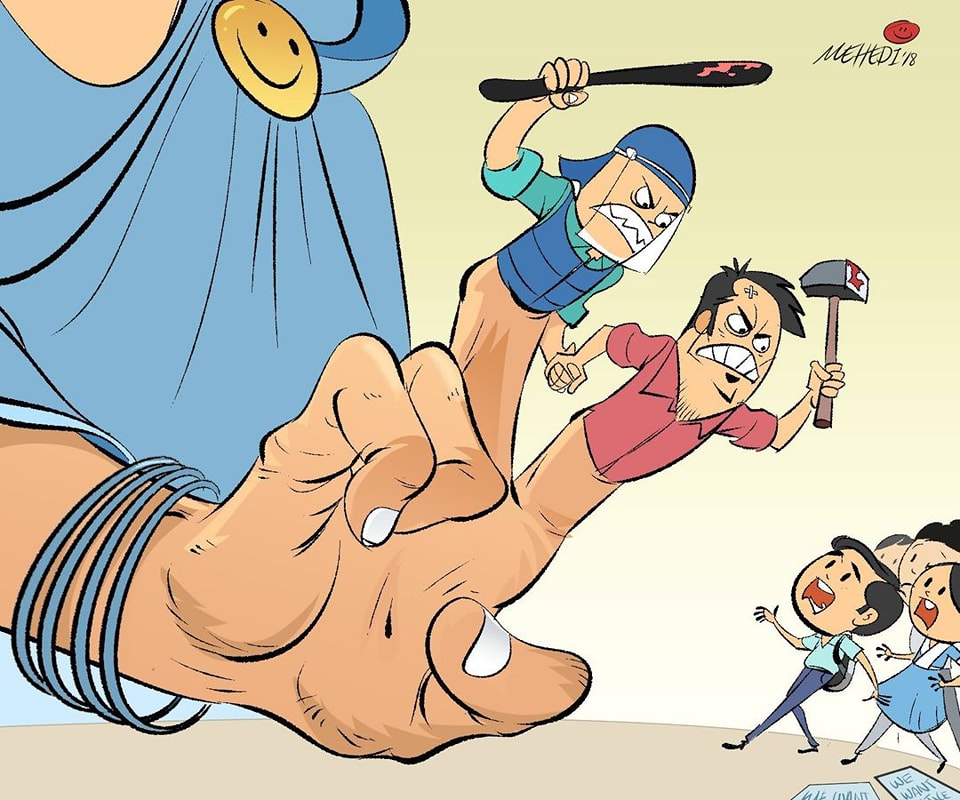

Figure 10, ©amarbarta.  Figure 11, ©Mehedi Haque.

Figure 11, ©Mehedi Haque.