This essay has been peer-reviewed by “The New Extremism” special issue editors (Adrienne Massanari and David Golumbia), and the b2o: An Online Journal editorial board.

Recently something rather unexpected happened. Curtis Yarvin began writing again. A decade ago, back in the spotty youth of the internet when blogs meant something, Yarvin, a Silicon Valley computer programmer, made a cult name for himself under the nom de plume of reactionary political philosopher Mencius Moldbug. Often memed, frequently cited as an important ancestor of the “alt-right” (but largely left unread) and father of the online political movement known as NRx/neo-reaction (which has been declared dead endlessly since at least 2013), Moldbug may well be the only notable political philosopher wholly created by and disseminated through the internet.

In his journey from Austrian Economics to attempting to update early modern absolute monarchy for the information age, Yarvin regularly churned out tens of thousands of word screeds on his blog Unqualified Reservations (UR) about the need to privatise the state and hand it over to an efficient CEO monarch to keep progressives out, the Christian roots of progressivism, and encomia to nineteenth century Romantic Thomas Carlyle. All of this was so liberally coated in rhetorical irony and Carlylean bombast that it was often difficult to tell what was supposed to be serious and what was not. Moldbug was among the first to discover the power of reactionary post-irony, though these days of course, playing long-read rhetorical games to affect ideological change seems a rather primitive affair. The work of post-irony can now be compressed into a couple of memes very easily.

Between 2007 and 2010 Moldbug was immensely prolific. Thereafter UR petered off as Yarvin turned his efforts increasingly towards developing a blockchain-based data-storage scheme called Urbit.[1] By 2014, when Moldbug began to become a household name across the internet as the social media platforms were increasingly politicised, Moldbug was pretty much finished writing. In April 2016 UR was wrapped up with a “Coda” declaring that it had “fulfilled its purpose.” The same month attendees threatened to withdraw from the LambdaConf computing conference because the “proslavery” Yarvin would be speaking at it (Towsend 2016).[2] To this Yarvin (2016a) wrote a reply insisting on the innocence of his Moldbuggian stage as simply a matter of curiosity about ideology. The same year in an open Q&A session about Urbit on Reddit, Yarvin (2016b) was more than happy to answer some questions about Moldbug and defend both projects as parts of a dual mission to democratise the current monopolies controlling the internet and to dedemocratise politics for the sake of enlightened monopoly.

In early 2017, following Trump’s election, rumours began to circulate that Yarvin was in communication with Steve Bannon, though nothing came of this (Matthews 2017b). Around the same time Yarvin was quoted as supporting single-payer healthcare (Matthews 2017a). News also surfaced that Yarvin was on a list of people to be thrown off Google’s premises, should he ever make a visit (Atavisionary 2018). Then, early in 2019, Yarvin (2019a) quit Urbit after seventeen years on the project, causing some to wonder whether Moldbug might now make a return. Old rumours also began to get about the place that Yarvin was behind Nietzschean Twitter reactionary Bronze Age Pervert (BAP), especially after Yarvin passed a copy of BAP’s book Bronze Age Mindset to Trumpist intellectual Michael Anton (2019) with the insistence that this was what “the kids” are into these days. And now Yarvin has started publishing again, under his own name, a decade on from the salad days of UR. On the 27th of September 2019 the first of a five-part essay for the conservative Claremont Institute’s The American Mind landed, titled “The Clear Pill.”

If Moldbug/Yarvin is famous for one thing, it is that he’s the fellow who put the symbol of the “red pill” into reactionary discourse. The “Clear Pill” promises to be a reset of ideology in which progressivism, constitutionalism and fascism will each receive an “intervention” through their own language and values to show up how “ineffectual” each is (Yarvin 2019b). Thus far this “clear pill” sounds all rather typically Moldbuggian–for Yarvin it has always been about resetting the state and the rhetoric of undoing brainwashing. Anyone passingly familiar with the oeuvre of Moldbug knows that Yarvin is more than capable of speaking all three of these political dialects reasonably well, even if, as Elizabeth Sandifer (2017) astutely notes, Moldbug is so deep in neoliberal TINA, he is unable to take Marxism seriously as a contemporary opponent at all. For Moldbug the American liberal pursuit of equality was always more “communist” than the USSR, which is to say, paranoid reactionary hyperbole aside, that he only ever regarded Marxism as an early phase of progressivism.

And yet, six months on from the first part of the “Clear Pill”, only a second of the promised five parts has thus far been published. Part two (Yarvin 2019c), or “A Theory of Pervasive Error” appeared on the 25th of November, and, so one might surmise, even the most die-hard Moldbug-fans must have found it somewhat lacking. The initial purpose of the piece seems to be to outline a theory of human desire that utilises the Platonic language of thymos (courageous spirit), but ends up sounding far closer to a Neo-Darwinian Hobbes than anything else. Human beings are petty and selfish beasts, we are encouraged to believe. The essay meanders on until it finally arrives at the simple old Moldbuggian point that because liberal “experts” in governance and science have a touted monopoly on truth, they should not automatically be trusted. That’s it. By taking such the long way around to say something so simple and banal, the result is more than a little anticlimactic. Perhaps after all these years the bounce has gone out of Yarvin’s bungy; his lemonade has gone flat.

The only other piece to appear on The American Mind from Yarvin since “A Theory of Pervasive Error” has not been part of this “Clear Pill” series, but a stand-alone essay published on the 1st of February 2020 titled “The Missionary Virus”. In this Yarvin argues that the recent coronavirus pandemic offers an unparallel opportunity to dismantle American “internationalism” and reboot a politically and culturally multi-polar world while economic globalisation continues. Imagine, Yarvin asks the reader, what it would be like if the virus did not go away and the travel bans lasted not a month, but a decade, or centuries. One thing can be said about this essay that cannot be said of the “Clear Pill” so far – at very least it is entertaining. Perhaps parts three to five of the “Clear Pill” will actually say something interesting after all.

Indeed there are all sorts of questions that are still left unanswered. Will the crescendo of part five simply restate the need to privatise governance and let the market system work? Will Yarvin take some drastic new turn or even disown Moldbug? Will he finally acknowledge eccentric death-cultist Nick Land, who, for the best part of this decade has largely been the “king” of NRx as a political ideology? We must wait and see.

***

Obviously, a great many people of all manner of political bents will be lining up to release their takes on the “Clear Pill” when it is finally done and dusted. I most certainly will be among them because, sad to say, I’ve been trying to work out Moldbug/Yarvin for years now. It’s very easy to brush him off as something archaic and nasty and even structurally predictable–a little racist ghoul who wants a CEO emperor–a desublimation of the Silicon Valley unconscious, a monstrous giving the game away about the fears and imperial pretensions of our techno-optimist masters. On this account Moldbug is very, very important indeed. Ten years ago, for Moldbug the solution was as simple as handing over California to Steve Jobs to run as a business, because Steve Jobs is very good at solving problems. The Moldbuggian wedge (esp. 2008a) was the belief that in the US, the two elite groups are “Brahmin” progressive intellectuals (who are bad) and the pragmatic businessmen (who are good), which is bizarrely very close to the recent terminology (but not ideology) of Thomas Piketty’s research (2018) on American and European elites in the Post-War Period.

Nevertheless, today the remnants of Moldbuggery as an ideology seem to spend their time bemoaning “woke capital”–that those with the talents and power to make something like Moldbug’s “patchwork” of privatised city states come true all seem to be believers in the various progressive gender and racial talking points of the present. But here’s the thing–Moldbug was never one to spend his time huffing and puffing about gender politics like just so many of his tradcath monarchist and other old school reactionary fans do, who somehow seem to imagine him as some new Joseph de Maistre. In spite of his night terrors about ghetto warlords and migrant invasion (see: Moldbug 2007d, 2008a), Moldbug/Yarvin always made efforts to appeal to “open-minded progressives”–there will always be room in the “patchwork” for dope and death metal (2008c); a privatised California’s welfare system of dividends would be so good it’d give the sick bionic wings (2008b: 99); prison in the future will be replaced by being put to sleep forever in VR (2009e); the American Empire sucks because it pretends that the world is made of independent countries, but rather than improving things, it keeps them as quashed clients and puppets (esp. 2008b).

But what if Moldbug always-already was “woke capital?” As I have written at length elsewhere (Ratcliffe 2018a, 2018b), the godawful possibility is that Mencius Moldbug was a kind of political basilisk that once thought, cannot be unthought–that he is a left liberal arriving from a cursed future, the obscene image of the juggernaut of hyper-capital with a human face haphazardly sutured to the front of it, like one of those awful homemade Thomas the Tank animations one finds at the bottom of YouTube at three in the morning. Although she doesn’t mention Moldbug, Vicky Osterweil’s diagnosis of a Silicon Valley liberal “left fascism” decidedly hits the nail on the head concerning certain aspirations of Amazon and friends to buy up whole towns and to remake the globe:

Rather than invoke Herrenvolk principles and citizenship based on blood and soil, these left fascists will build nations of “choice” built around brand loyalty and service use. Rather than citizens, there will be customers and consumers, CEOs and boards instead of presidents and congresses, terms of service instead of social contracts. Workers will be policed by privatized paramilitaries and live in company towns. This is, in fact, how much of early colonialism worked, with its chartered joint-stock companies running plantation microstates on opposite sides of the world. Instead of the crown, however, there will be the global market: no empire, just capital. (Osterweil 2017)

Does this not sound so terribly Moldbuggian that it makes the skin itch? Against this sort of thing what is needed is a healthy combination of strong local communities committed to telling Google and Amazon to shove it–or whatever else it is that might succeed them–matched with commitments by governments to break up these companies and prevent private police forces. Even better would of course be nationalisation of these companies and handing them over to worker-control. Nonetheless, the dismal old Guild Socialist localist in me finds contemporary dreams of simply nationalising the miserable and soulless infrastructure of our present, such as we find in recent texts like The People’s Republic of Walmart (Phillips and Rozworski 2019), not only supremely vulgarian, but at present as unlikely as the possibility that the neo-reactionaries will ever get their future of a consciously reactionary world governed by Megacorps.

For now, at least, we’re all stuck with the political and corporate monopolies we let happen–none of us can “head for the exit,” not even the Zuck. We’re all locked in the same room together. Leviathan is not going to be letting anyone’s people go, not for all the hyperstitional meme magic of a couple of cut-price Twitter occultists thinking that NRx v.2.0 is simply supporting all secession movements and waiting for a rich papa to make the private state a reality. Liberalism is a jealous “Mortalle God,” as its primordial violent father Thomas Hobbes would say. As we will see later, Hobbes remains the most important figure for understanding NRx, its “woke” corpocratic mirrored other, and liberalism in general.

The possibility of the “left fascist” Moldbug draws out attention to the oft-overlooked fact that there was more than one Moldbugpolitik outlined on UR over the years. I think I’ve managed to isolate at least three strains thus far. Moldbug 1 is the Moldbug we’ve been talking about. This is the “neocameralist” of the 2008 “Open Letter to Open-Minded Progressives” who is simply trying to make anarcho-capitalist Hans Hermann Hoppe’s “patchwork” of private states sound cooler by adding some extra monarchy aesthetics and criticism of the American Empire (Moldbug 2008b). This is the Moldbug from which (with an added injection of race and IQ sorcery and the removal of Carlyle in favour of Malthus) Nick Land builds his variant of NRx. You have ideology as a parasitic virus, the powerlessness of populist reaction, open borders chaos, shiny futuristic city states. While this Moldbug might on the surface look like he is all about the sovereign One–the single absolute ruler–the “king” is of course simply someone hired by a body of shareholders to get their city to make money. If the mediaeval Christian monarch had “two bodies”–one mortal and the other his immortal perpetuation down the generations–then the immortal body of the Moldbuggian CEO is that of the corporate personhood of the joint stock company behind the scenes. You may go to sleep for hundreds of years, but when you wake up Wayland-Yutani will still be there.

Moldbug 2, from the “Gentle Introduction,” on the other hand, is the Moldbug (2009d) of what its section 9d calls “The Plinth”: an unabashed attempt to theorise a vanguard party like Hitler’s or Lenin’s with cells everywhere and then simply taking over government. This is the “populist” Moldbug that Nick Land doesn’t want you to know about, though some of the more “trad” reactionaries have been interested in it, as I have discussed in the past on my Mechanical Owl blog (Ratcliffe 2018a, 2018b). Moldbug 2 is a total departure from Moldbug 1 because the earlier version seemed so adamantly convinced that popular reaction in America is instantly crushed by the liberal media: it is “a mile wide and an inch thick … like taking on the Death Star with a laser pointer” (2008b, 116). One wonders what Moldbug 2 thinks of Trumpism and its effectiveness thus far.

Then we come to Moldbug 3. This is a strange theocratic Moldbug (2013) we find in a single late post on UR, in which he praises the political coherence and mass appeal that Christian reactionaries in the US such as Lawrence Auster sometimes seem to possess. We are told by Moldbug that because of this it is highly likely that “when our dark age ends and the kings return, if ever, it will be under any banner but the Cross,” which of course the tradcaths have endlessly cut and pasted across the internet without context. What is most interesting about Moldbug 3 is that Moldbug/Yarvin is an avowed atheist “secular humanist.” In the post in question he even writes about telling his daughter that God is just Santa for grown-ups. It is, however, not so uncommon to find atheist reactionaries who believe that Christianity has an important utility as a “social technology”–whether for supporting patriarchy, keeping Islam at bay or providing a collective myth that can be used to bolster nationalism.

Nonetheless, this Moldbug 3 stands in stark contrast to the main Moldbuggian discourse we find in the 2007-8 Moldbug 1 in which Christianity is found historically to be the root behind “progressivism.” Moldbug 1 (2008b, 58 & 104-7) is especially fond of colourful language about American political history as “creeping Calvinism,” “Quaker thuggery” and “applied Christianity” concerning the pursuit of equality and universalism. This is perhaps why I keep coming back to Moldbug and giving him the time of day. Moldbug 1’s only truly remarkable idea was his grand narrative about millenarianism and modern liberal politics. Millenarianism is the idea of the imminent (and immanent) arrival of a “Third Age” of Christianity in which the world becomes a realm of plenty and universal equality after the old order is scoured from the Earth by the Apocalypse. As Revelation 21:4 promises: “And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away.” As we will see below, such notions have had a profound formative effect on the progress narratives of modernity.

Moldbug 1 avidly believed that progressivism is the mainstream American political tradition, a “W-Force” child of Calvinist and Quaker universalism that developed through the seventeenth century British Whigs. In a very early blog entry entitled “Universalism: Post-War Progressivism as a Christian Sect” Moldbug claims:

Universalists, as descendants of Calvin’s postmillenial eschatology, are in the business of building God’s kingdom on Earth. (The original postmillennialists believed that once this kingdom was built, Christ would return–a theological spandrel long since discarded.) The city-on-a-hill vision is a continuous tradition from John Winthrop to Barack Obama. In Britain, the closely-related Evangelical movement used the term “New Jerusalem,” which I’m afraid never really made it across the pond, but expresses the vision perhaps best of all… What’s really impressive about Universalism is the way in which this messianic teenage fantasy power-trip has attracted, and continues to attract, so many people who don’t believe at all in the spirit world, only smoke weed on the weekends, and think of themselves as sensible and down-to-earth. Of course, the belief that all Universalist ideals can be justified by reason alone is a necessary condition. But Christian apologists have been deriving Christianity from pure reason since St. Augustine. You’d think these supposedly-skeptical thinkers would be a little more skeptical. (Moldbug 2007a)

Moldbuggian rhetoric aside, it is difficult to find anything shocking about the millenarian ancestry of progressive thought. But then again it is not 2007 and thankfully our collective social neck is not quite as gormlessly bearded as it once was. I think it is a dashed good thing indeed that there is a long history of marvellous radical Christians like the Baroque Levellers and Diggers of the Civil War who “turned the world upside down” (Hill 1991), the Anabaptists of Thomas Müntzer who called for the princes to be killed (Cohn 1962), and even earlier, mediaevals like John Ball, who famously asked during the Peasant’s Revolt “When Adam delved and Eve span, who then was a Gentleman?” One cannot do nigh on two millennia of something and not have it rub off in a myriad of strange ways, even if the End always seems to defer and remain not yet. America especially is no exception to this.

As Jonathan Kirsch (2006, 185) in his astounding History of the End of the World pertinently puts it, America is the land of two millenarian “tectonic plates” that developed out of the radical protestant belief that the New World was where the New Israel would be built. The first plate, that of aspirations towards theocratic “dominionism” and purchasers of rapture insurance is the obvious one and remains primordial. The other, however, increasingly secularised from the 17th century under the belief that America was the exceptionalist future land of techno-commercial and social progress. The “two plates” give us all the worst parts of Moldbug 3 and Moldbug 1, the theocrat often predictably accompanied by the vilest forms of prosperity theology and racism and so too the Silicon Valley techno-optimist. But this weird mutant geology also gives us the only force Moldbug could really be scared of, the ghost of a radical “applied Christianity.” The gap between Moldbug 1 and Moldbug 3 must be drawn out in consideration of hidden theological core of NRx itself. So too will I suggest that to attempt to recuperate and come to love the Moldbuggian accusation of “Quaker thuggery” might be a very useful idea indeed.

***

There is nothing odd at all about the notion that a great deal of modern values are secularised theological ones. Nearly a century ago now Max Weber (1976) and R. H. Tawney (1948) famously had a great deal of insightful things to say about Anglo-American Calvinism, the protestant work ethic, and the spirit of capital. Moldbug, curiously, mentions Weber only once to my knowledge, concerning the ruler and “charisma” (Moldbug 2009a), yet somehow manages to avoid having to talk about the theological ancestry of his own very American arch-capitalist belief system. For that matter, he never says anything about one of the most frequently-cited (but generally rather shallowly analysed) heroes of monarchist reactionaries, Carl Schmitt.[3] In the 1920s Schmitt (2005) launched the field of juridical genealogical investigation called “political theology” that declared that the modern secular ruler is modelled on the voluntarist God of Ockham who acts with trans-rational potentia absoluta (absolute power) to create a miraculous “state of exception” during emergencies.

Through leftist thinkers such as Giorgio Agamben (esp. 2011) and Roberto Esposito (2015) “political theology” has undergone a revival in recent years, exploring the political-theological genealogies of subjects such as neoliberal economism, personhood, human rights, ownership, victim-blaming and imperialism. So too from Ernst Bloch (2000) and Walter Benjamin (1940) to Slavoj Žižek (with Gunjevic 2012) there has long been a recognition of the Jewish and Christian apocalyptic and universalist roots of Marxism. From the more conservative side, not only Schmitt, but Oswald Spengler (1926) in his discourse on “Faust” and “Gothic Christianity,” Eric Voegelin (2000a) on “Gnosticism,” and Carl Löwith (1949) too, all had a great number of valuable things to say about the history of secularisation and the pursuit of the millennium. Thus, when NRx torchbearer Nick Land claimed in a 2017 interview for reactionary podcast Red Ice Radio that “hardly anyone, still, has really begun to dig down into [the destiny of Western Christianity’s] contemporary relevance” concerning leftist universalisms (Land and Palmgren 2017, 27m.20s-28m.10s), it is hard to think how Land could be any more incorrect if he tried.

But from where did Moldbug get his “creeping Calvinism” thesis? I have often wondered if it was from Eric Voegelin, who occasionally garners a passing mention or two in American “paleocon” circles. Voegelin (2000b, 71-2 & 185-7) argued that in the Anglosphere something very strange had happened after the Reformation, a “Second Reformation” in which the newer branches of Protestantism, such as Wesleyanism and Methodism, had been instrumental in the push towards democratisation through their belief in social equality and community participation. This, so Voegelin believed, had immunised the Anglosphere against the worst of Fascism, Communism and Positivism compared with continental Europe. Voegelin (2000b, 61-2), however, was also very much aware of the less savoury aspects of this “Second Reformation.” The idea of building a totalising community of elect believers could end up in the sort of paranoid pressure cooker epitomised by Calvinist Geneva, or many of the other “perfectionist” efforts that we find in early America attempting to build the New Israel. It is a startling idea indeed to ponder whether the American reactionary religious commune and the experimental hippie commune might be two sides of the same coin of “election.” Even stranger would be to wonder if the inverse of the language of theocratic “dominionism” is that of egalitarian social justice.

Nonetheless, the only mention Yarvin has ever made of Voegelin was during his apologia of Moldbug in relation to the LambdaConf scandal (2016a). Here Voegelin is invoked in relation to his thesis that the variety of Christian thought that has informed so many of modernity’s “political religions” is Gnostic–that is, it makes a claim to totalising knowledge of reality and its manipulability in order to replace God with its own unshakeable race of supermen as the agents of history. To Voegelin in order to produce his total system, the Gnostic, whether Positivist, Fascist, Marxist or Liberal, must forbid the asking of questions about doctrine and must selectively forget extremely obvious problems that could get in the way of remaking the world. As Yarvin (2016a) quotes him:

In the Gnostic dream world…non-recognition of reality is the first principle. As a consequence, types of action that would be considered as morally insane because of the effects that they will have will be considered moral in the dream world. (Voegelin 2000a, 226)

Voegelin continues that the gap between the real and the desired world is then used to project the immorality onto some other for not behaving in accordance with the thinker’s personal fantasies. Yarvin (2016a) utilises this to claim that what he finds real may seem like a daydream to others and vice versa. Now, all this may well have simply been Yarvin attempting to find an obscure thinker he liked to feed back to left liberals the cliché cultural relativism and perspectivism he believed they would accept. There’s little chance anyone would have accepted the idea that it’s okay to be reactionary simply on the basis of it’s just, like, my opinion, man. The thought that deep down “free speech advocate” Curtis Yarvin (as his reply to his critics titles him) might really be Richard Rorty saying we’re all numinously entitled to our own truths and will just live together in pragmatic tolerance is rather hilarious. Moreover, it is hard to believe that he could possibly read Voegelin so badly as to think that he’s saying that we are all supposed to be deluded like this. To Voegelin, who was a highly complex Christian Platonic realist, this sort of consciousness was a very bad thing indeed.

Rather, the earliest articulations one might find of Moldbug’s “creeping Calvinism” thesis (2007a, 2007b) seem to come from a different place, from a previously undeveloped libertarian discourse that anarcho-capitalist Murray Rothbard had conspiratorially hinted at in “World War I as Fulfillment: Power and the Intellectuals”:

Also animating both groups of progressives was a postmillennial pietist Protestantism that had conquered “Yankee” areas of northern Protestantism by the 1830s and had impelled the pietists to use local, state, and finally federal governments to stamp out “sin,” to make America and eventually the world holy, and thereby to bring about the Kingdom of God on earth. The victory of the Bryanite forces at the Democratic national convention of 1896 destroyed the Democratic Party as the vehicle of “liturgical” Roman Catholics and German Lutherans devoted to personal liberty and laissez faire and created the roughly homogenized and relatively non-ideological party system we have today. After the turn of the century, this development created an ideological and power vacuum for the expanding number of progressive technocrats and administrators to fill. In that way, the locus of government shifted from the legislature, at least partially subject to democratic check, to the oligarchic and technocratic executive branch. (Rothbard 1989)

Can we trust Rothbard as an historian? When American libertarianism began to self-consciously develop after WWII and create for itself a grand narrative against the dominant Keynesian economic consensus of the time, it fixated on and hypertrophied conservative beliefs that the New Deal and events leading up to it were the Fall and betrayal of a “real America” of laissez faire and free trade, transforming the Gilded Age into a primaeval Golden Age now lost. In the earliest stages of his thought, Moldbug 1 simply seems to be working from this rather typical right-wing American position. He even insists (2008b, 193) that should 1908 America suddenly appear in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, it would be able to outcompete 2008 America hands down. Nonetheless, Rothbard appears to have opened up the religious dimension as an answer for this Fall to Moldbug. In early Moldbug 1 (2007a, 2007b) the Fall is augmented with obscure conservative texts on the role played by the evangelical churches in encouraging the New Deal, occasionally supplemented by more mainstream sources now forgotten.

For instance, in the June 2007 UR post “A Short History of Ultracalvinism,” we find a small 16th of March 1942 article from Time magazine cited, titled ‘American Malvern” that reports on “the high spots of organized U.S. Protestantism’s super-protestant new program for a just and durable peace after World War II.” These include “Complete abandonment of U.S. isolationism…International control of all armies & navies…A universal system of money so planned as to prevent inflation and deflation… Autonomy for all subject and colonial peoples” (with much better treatment for Negroes…).” Should it be at all shocking that the churches, both liberal and conservative, ever had a key role to play in encouraging the idea of a beneficent American imperialism? No, I do not think it is, not a jot. Moldbug, however, simply takes the article to indicate that in the intervening half century Time “has become as stupid as its audience,” the implication being that the average reader in 1942 would have been as suspicious as 2007 post-Iraq II Moldbug about America’s global “civilising mission.” Let us not forget that the tiny isolationist paleoconservative movement of people like Pat Buchanan was only rediscovered by Moldbug, Richard Spencer and others following the collapse of faith in the myths of neo-con missionary interventionism with Iraq War II. As Moldbug (2008b, 6) says at the start of his “Open Letter,” in recognition of both the openly religious and crypto-religious faith behind interventionism, the American military was now busy “doing donuts on the road to Damascus.”

Having been led by Rothbard back to the 19th century in search for a solution to the Fall, Moldbug then decided to go back much further into the 17th century to trace a history of protestant radicals undermining the power of the absolute monarch. Moldbug’s actual evidence for this period is very thin. We find Hooker’s complaints about non-conformists, but that is about it. One might expect Moldbug to cite something like Christopher Hill’s The World Turned Upside Down (1991) on the relevance of 17th century British radical non-conformism to twentieth century politics or the astounding appendix on the pantheistic and free-love heresies of the Ranters in the 1962 edition of Norman Cohn’s The Pursuit of the Millennium. He never does.

But why is Moldbug so interested in early modern absolutism? This he seems to have acquired from anarcho-capitalist Hans Hermann Hoppe’s anti-democratic screed Democracy: The God That Failed (2007) in which monarchism is celebrated for being simply the vast private ownership of land. The absolute ruler is thus reinvented as the ultimate capitalist landlord, the perfect model for creating a future world of privatized territories. One is strongly reminded of Xenophon’s Oeconomicus in which the Persian Great King is represented as simply a very big and powerful homesteader in a world of patriarchal homesteaders. Nevertheless, the fact should remain that Austrian Economics is infamous for its beliefs that capitalism has always existed and that economics began not in primitive accumulation or ritualized gift economies, but in barter. There are no changes in economic modes for the Austrian, and the long history of the temple in the development of money, loans and credit is completely ignored. The eternal foe is simply those who would threaten the natural right of the eternal “rugged individualist’s” private property.

Thus, for Moldbug, the history of modernity is reinvented as a wrong turn–the rise of Christian radical egalitarian movements through the Whig Party who sought to undermine the rights of the absolute ruler as private owner. One wonders what Moldbug would make of Carl Schmitt’s (2009) marvelous Hamlet or Hecuba in which Shakespeare’s character is found to reflect the absolutist James I as a weak decision-maker being undermined by the growing forces of piratical capital. For Schmitt modern techno-capitalism’s desire to “neutralise” political violence requires the quashing of the absolute ruler of decision. But then again, Moldbug seems absolutely blind to ever having to ask about the mercantile aspects of the birth of radical, egalitarian “creeping Calvinism” that Tawney in particular addressed so well. He is never able to realise, even in his belief that the American elite is the radical universalist intellectuals versus the merchants, that genealogically much of this is an “inhouse” Anglo political-theological problem.

The way Moldbug sweetens the anti-democratic rhetoric of Hoppe is with recourse to Thomas Carlyle. Although now largely unread, Carlyle was one of the most widely-popular political and historical authors of the 19th century, infamous for his impassioned appeals against laissez faire abandonment of the poor to poverty and starvation (see esp. Carlyle 1915, esp. 85-6; Carlyle 1971, 71-84). Carlyle’s answer to these problems was better rulers, Great Men, whom he could find in abundance and celebrate in just about every other period of history except his own. This caused Carlyle to become increasingly bitter and apocalyptic as time wore on, leading to what Voegelinian Richard Bishirjian (1976) aptly identifies as a thoroughly “Gnostic” outlook in search of some kind of soterical God-man ruler to save the world from chaos and to bring about the millennium.

While it is obvious that Yarvin loves Carlyle for his florid language (who doesn’t?), the real appeal seems to be his paternalism, the conviction that the true Great Man should care for those who are subservient to him. Moldbug 1 especially wants you to know that he cares, that in 2008 the Great Man looks like Steve Jobs because Steve Jobs is cool and cares too. When Moldbug (2008b, 117) argues that black Americans living in the ghetto should be forcibly re-educated in panopticon communities, this is because he cares compared with liberals who have abandoned them to crime and welfare. The obvious model here is Carlyle’s (1915, 302-33) “Negro Question” speech, in which he had insisted to his shocked 19th century liberal audience that he really did care when he argued that freed blacks in the Caribbean should be forced to labour for their masters for their own moral good rather than living on cheap pumpkins.

One should emphasise that Moldbug’s affection for Carlyle is in strict contrast to the few other libertarians who seem to have ever heard of him, predictably regarding him as a feudal remnant, a bad guy who defended slavery, compared with noble 19th c. laissez faire liberals (e.g. Levy 2000). On the slavery question, Moldbug (2009b) can certainly admit that his beloved Carlyle wasn’t “perfect,” but perhaps only because he dismissed the “financial” side of things. Yet, just when we might be expecting Moldbug to try to fold chattel slavery into some kind of wretched anarcho-capitalist discourse that it was just another form of harmless voluntary wage labour all along (and he does very nearly get there), he instead takes a sharp turn towards romanticising feudal hierarchy and comparing it to the strict efficiency of Japanese companies. In a direct homage to Carlyle we find him castigating liberalism for allowing Haiti to become a failed state. Nonetheless, Moldbug is, without a doubt, a “proslavery” thinker: he even believes some people (especially those with a low IQ) are “natural slaves,” but this shouldn’t mean that they need to be treated cruelly. The new corporate Great Men feudalists of the 21st century will treat them very nicely, thank you very much indeed.

It is ponderously obvious that Silicon Valley has long possessed a penchant for believing that its “thought leaders” are of equal historical importance to the Great Men of the past, as is evidenced by the great sea of pulpy awfulness on learning the business secrets of Julius Caesar and Genghis Khan that spills out of the self-help section of crummy bookstores everywhere. Most notable is former student of anthropologist René Girard and NRx-ally Peter Thiel’s gormless Zero to One (2014) that pulls no punches in comparing today’s entrepreneurs and celebrities to sacred kings. Seen in this context, Moldbug is doing very little that is original. It’s certainly easy to scoff at the notion of Divus Marcus Zuccus and so on, but, as has been emphasised, one should not underestimate for a moment the possibility of a Silicon “left fascism” with its garish attempt at appearing kind and “progressive.” It is perhaps not necessarily that our Silicon masters literally wish they were pharaoh, but, far worse, that perhaps they think that they already benevolently determine the direction of the world and should simply branch out slowly into governance in order to formalise it for its own good. Maybe like Carlyle they’ll even pay their wage-slave chattels the compliment of saying how handsome and cheerful they think they look when put to work for a pittance with no toilet breaks. Hang on–Amazon already does that.

***

What Moldbug is doing with his discourse on “creeping Calvinism” is not a “secularisation thesis” in the manner of Weber, wherein one is simply looking for the roots of current social formations, however dour they might be, or a “political theology” as Schmitt and his Foucauldian leftist successors do, wherein it is often debated whether an “exit” to the political-theological machine is even possible. What Moldbug is doing is part and parcel with a certain kind of Enlightenment ideological discourse and genealogical fallacy–compare anything to a religion, you demystify and delegitimise it; if you find that something actually has religious roots this is thus even better for delegitimising it as fantasy. One only need think of John Gray’s Black Mass (2007), written around the same time Moldbug was actively blogging, in which the Christian millenarian ancestry of modern ideologies from Communism and Anarchism to the American liberal “end of history” all testify to the idea that progress is a rather worthless religious delusion.

Perhaps this sort of thing is simply a vulgar attempt to “own the libs” by rubbing in the educated leftist sceptic’s face the idea that he is a religious lunatic. As an educated leftist religious lunatic, I am not fazed one iota by this. One could simply stop here and say no more, but what Moldbug (and Gray) are up to has in itself very particular crypto-theological roots worth discussing. Both Moldbug and Gray are deployers of a cynical materialism most clearly presaged in Thomas Hobbes’s need to cut down the competing religious claims of his dissonant age of Behemoth (Civil War) by reinforcing the image of man as little more than a dangerous animal that needs to be kept in line. Man is a wolf to man; life is nasty, brutal and short under the state of nature. For Gray the political religions have been a psychotic disaster unable to grasp Neo-Darwinian cosmic indifference. Climate change is the only real Apocalypse, likely to bring what fellow climate-cynic James Lovelock calls “global decline into a chaotic world ruled by brutal war lords on a devastated Earth” (Lovelock 2007, 154; cf. Gray 2007, 202). For Moldbug the Behemoth is instead liberal naïveté about “open borders.” He wants to tell you that America is run by a “Cathedral” of crazed post-Christian hippies who are so blinded by their ideological “blue pill” called “Millennium” (2008b, 241), that they cannot possibly understand that what they are doing is dangerous. The perfect Hobbesian Moldbuggism is perhaps found in Yarvin’s Urbit “Ask Me Anything” session on Reddit of all places:

I think that when we use the word “human” we often really mean “angel.” So, yes: we are all subhuman. Black people included. I’m not just saying this: I think the main flaw of 20th-century political systems is that they’re designed to govern angels. If you plan for apes and allow for angels, I think you get a much better result (especially when there’s a Y chromosome in the mix). (Yarvin 2016b)

What hard cruel realism! Surely Yarvin is the modern sceptical Hobbes speaking the truth to the deluded, just as Hobbes’ works were blamed in parliament for being a cause of God’s wrath visiting England in the form of the Great Fire of 1666! But, strangely, Moldbug has close to nothing to say about Hobbes, except perhaps a passing comment or two that in the 17th c. as a materialist he was the “leftist” compared with the divine right absolutism of his contemporaries such as Robert Filmer (Moldbug 2009c). Amusingly some Ur-Catholic reactionary thinkers have considered Moldbug little more than a godless “leftist” for his materialism and have compared him explicitly to Hobbes (Charlton 2013; cf. Nostalgebraist 2016). Several centuries earlier of course the idea of an absolute monarch on the basis of divine right would have been regarded as equally radical and heretical for its usurpation of the authority of the church and the complex myriad of local political institutions, as John Milbank (2019) has recently pointed out to the NRx and “post-liberal” crowd at Jacobite. But then again Moldbug has nothing to say about the Middle Ages at all. History starts with absolutism as though it had always been in place. More than anything this should draw our attention back, once again, to the fact that Moldbug 1’s claim to “Jacobitism” is all shallow aesthetics to stitch together Hoppe and Silicon Valley aspirations towards governance. Nonetheless, Moldbug cannot escape from Hobbes and his legacy so easily.

As John Milbank and Adrian Pabst (2015, 22-24) argue, in the tradition of Tawney’s secularisation thesis on British Calvinism and capitalism, with Hobbes what we see is not some new cynical variant of a reborn version of antique materialism, but the materialist rendering of the Anglo Calvinist belief in absolute human depravity and selfishness. This attitude developed from the rising emergence of a society that had uprooted and alienated agricultural labour, professionalised governance and established its grip on the New World primarily through piracy. Man is a very fallen and wicked little animal indeed to the cynical leveller and this, so Milbank and Pabst claim, continues to haunt the Anglo mindset through John Locke, Bernard Mandeville and Thomas Malthus, down to liberal selfishness in the present. That which appears sceptical and “realist” concerning human nature stems from a debased Christianity that cannot imagine the human soul to have anything good in it at all but a selfishness that might be put to use making contracts, consuming and perishing.

This alternative aspect of “creeping Calvinist” especially seems to leak out of Nick Land’s “Dark Enlightenment” (2013 pt1) of “Hobbesian undercurrents” like there’s no tomorrow. So too his race and IQ “naturalism” and neo-reactionary deity Gnon (Nature or Nature’s God) that punishes those who go against the “nature of things.” Land’s decades-long revulsion and boredom with the human and demonology of entities like Cthelll (2011, 498-9), the primaevally wounded world-soul of the Earth passing on its misery and horror to all its children, were already more than half-way there. If anything, this earlier more bombastic, body-horror-obsessed phase of Land’s thought has always smacked to me of the worst of Christian “vale of tears” masochism, as epitomised in Luther’s hyperbole that the Earth is “a gaping anus,” the “Devil’s arse,” a “worm bag” and a “rotten chicken’s crop” because of its domination by evil merchants. Perhaps Norman O. Brown’s (1959, 222-7) old Freudian political theology was correct to read in these sentiments of Luther’s the origin of the protestant work ethic and its fixation with accumulation as an extended “anal stage”–a masochistic falling in love with the world as shit. Land’s attempts in the 90s to embrace the consciously worst aspects of neoliberal TINA to its masochistic limits simply seems to recycle this process.

By now just about everyone with an internet connection is familiar with Land’s (2017a) eccentric views that the forces of capital are the real agent of history, some kind of “intelligent” insentient egregore. Nonetheless, as Jean-Pierre Dupuy (2014, 91-101) has argued in Economy and the Human Future there is something very similar to the dominant neoliberal view of the almighty economy today and the Calvinist belief in predestination–that only God knows who is saved and who is damned and that any and all human good and bad works are powerless before it. Land is torn between, on one hand. a kind of deterministic triumphalism sneering at any and all mass action as failed (2016), and, on the other hand, a kind of deep terror that salvation is very unlikely indeed–that the Anglosphere will collapse under immigrant invasion, that high IQ states with low birth-rates are “IQ shredders” (2017b), and that only some fantastical vision of “Neo-China” completing the system of cyberpunk idealism can make up for this. That, or simply the weak theurgy of “hyperstition”: trying to force memes into reality under the bizarre belief that what one is actually doing is bootstrapping an already-realised future that is retrojectively invading the present.

It is very much worth noting that while Land may have developed this invasion from the future idea from watching too many sci-fi films (see: Reynolds 2009), as Catherine Pickstock (2013, 55-8) has observed this retrojective motion is an integral part of his old hero Gilles Deleuze’s cosmology in Difference and Repetition (1994). Here, so she noted, “difference” bootstraps itself by invading from the future in a blatantly theurgical gesture reliant on mediaeval millenarian Joachim of Fiore’s belief in a Third Age that completes history (Deleuze 1994, 296-7; cf. Pickstock 2013, 57). Land, so one might say, seems to have exchanged the fantasy of pure difference in favour of all too ponderous identity in the form symbols like cyborgs, post-human supermen and AI overlords. These were symbols cooked up in the atmosphere of the Post-War Boom, when people were a great deal more confident that both Paradise and imminent Judgement Day were at hand; but then, like the millennium, these have remained put off, not yet, for all the rumours otherwise. That scholar of “Accelerationism” Benjamin Noys (2014, 63) made reference to Norman Cohn’s (1962) study of millenarianism Pursuit of the Millennium when he referred to Land’s ideas as “apocalyptic acceleration” was very much on the right track.

Land has a long history of being a hyperbolic contrarian, a sort of pantomime Satanist of theory. Elizabeth Sandifer (2017) has even considered whether the entire thing, from Land’s early left cyber-anarchism in the 1990s to his embrace of neo-reaction in the early 2010s, is one long postmodern “dirty joke.” Maybe Land became a neo-reactionary simply because he had run out of edge to lord, so to speak, and decided it was worth LARP-ing the evil capitalist Kantian white man attempting to immunise himself from the world he was pillaging, as Land’s first famous essay “Kant, Capital and the Prohibition of Incest” (Land 2011, 55-80) set out to oppose. Perhaps resentment for the cyberpunk future not arriving as quickly as he had imagined in the 90s was what led him to the “Dark Enlightenment’s” (2013 pt 1) condemnation of the welfare state as the chief means of the capacity for capital to waste itself rather than liberating technology. This self-wasting (though not on welfare) in order to cheat liberation with “antiproduction” was one of the few instances in which Deleuze and Guattari (1983, 262) took Freud’s dread “death instinct” seriously, it being Land’s (2011, 123-44 & esp. 261-88) pet cause for reinsertion into their work in the 1990s. Maybe Land dwelt so much on the “death instinct” that he ended up turning Deleuze and Guattari’s Reichian-Rousseauian rejection of Death back towards a more Freudian-Hobbesian position out of fear of human beastliness cancelling the future. All manner of things might be posed, but Land seems to have a strict policy of not explaining his shift, instead claiming that he was always an anarcho-capitalist all along and that much of his early work was simply naïve.

***

Thus, one thing then seems clear about NRx. It wants to tell you that human beings are fallen and dangerous creatures and that “progressivism” naively and conveniently forgets this fact. But does it really? Let us turn things around for a moment. It is very easy to acknowledge that the old meme of conservatism and reaction being based entirely in irrational fear and ignorance is a popular one, evidenced, obviously, by recourse to the shorthand of bigotry as -phobias. However, when I have put it to common or garden progressive types that they also seem to draw a great deal of their politics from threat perception and fear (climate change, the return of fascism, theocrats, that bigoted language is implicitly violent), one is often met with the reply that yes, but these threats are real. Out come the charts, out come the think-pieces and rarely is anyone ever convinced that anything but strategic silence and bad faith is at work. From all sides the world is filled with a great tribal refrain of “But why don’t you take X seriously? It is very dangerous!” “Because they do and they are terrible people who believe other terrible things.”

The internet is very good at endlessly reminding us of the existence of this species of communicational deadlock, but it is an aspect of human being that has existed long before the electronic “echo chamber.” For Schmitt (2005) this is the “friends vs enemies” division of the political-theological emergency, a great irrational Two based in the dualism of God and his people versus the Other. Thinkers such as Roberto Esposito (2015) have gone to great lengths to try to deconstruct this Two and its violent aspects–to the point of eccentrically claiming that to rid ourselves of it, the whole concept of “personhood” (theological and legal) would have to be done away with first. Esposito never tells us what such a “depersonalised” world in which all thought, guilt, authority and existence is deprivatised would look like. It seems almost impossible to imagine such a thing. Instead we remain stuck with incommensurate claims to the “right side of history” imagining that the apocalyptic day shall eventually come on which the Other is, at very least ideologically, completely eradicated.

This faith lies at the core of Moldbug’s “Open Letter” (2008b) and its dreams that his reactionary future will be so well-run, hi-tech, luxuriant and happy that socially “progressive” ideas will be reduced to the position that reactionary ones held in 2008: if not a hilarious lost cause, then something virulently dangerous that must be suppressed. In our era when it is often lamented, especially by the Left, that it has become impossible to conceive of a “different world,” perhaps the goad towards imagining such things again should be that the reactionary right is frequently not quite as afflicted by the omnipresent fear of recuperation and failure. Cross this with Silicon Valley techno-optimism, and no matter how ridiculous or facetious Moldbug’s visions of VR prisons or handing over the state to airline pilots to privatise it might seem (2008b, 216-7), the fact remains that he was naïve enough to stake a claim on the future when hardly anyone else would dare do such things. That should be concerning (and perhaps a little shameful).

But how did Moldbug get there? Social habitus of course plays a very important part in the formation of the political Two in our age. This is especially obvious regarding NRx, which seems mostly peopled by college-educated middle-class white guys reacting with boredom towards the largely left liberal cultural pod in which they have been raised and educated. Reaction promises a totally different series of moral imperatives and threat-perceptions, an exciting virgin land untouched by hardly a soul smarter than a rock since the days of Real Existing Fascism. The mixture of excitement and resentment at the fact that a whole ideological continent had long been reduced to Neo-Nazis in the trailer park was palpable in Moldbug writing a decade before the “alt-right.” At the opening of his early declaration of a search for a new politics, entitled “A Formalist Manifesto,” Moldbug says:

My beef with progressivism is that for at least the last 100 years, the vast majority of writers and thinkers and smart people in general have been progressives. Therefore, any intellectual in 2007, which unless there has been some kind of Internet space warp and my words are being carried live on Fox News, is anyone reading this, is basically marinated in progressive ideology. (Moldbug 2007c)

Even though a complex reactionary news-ecosystem now exists, there still remains a profound need for reaction to distance itself from the image of the conservative as the angry uncle shouting at Fox. As a friend once put it–you piss off anarchists by telling them to move to Somalia, you piss off Marxists by telling them to move to North Korea, you piss off Neo-Reactionaries by telling them to move to Alabama.

Nonetheless, a particularly curious side-effect of this acting out against “the libs” is the fact that Moldbug, like a great many reactionaries today lurching between fantasies of some Sorosian League of Doom and “clownworld,” can never make his mind up whether his “Brahmin” enemies are evil geniuses trying to unite “high and low against the middle” by teaming up with “Dalit” POCs to replace white America (2008a), or zombified morons unable to perceive that: “History is not over. Oh, no. We are still living it. Perhaps we are in the positions of the French of 1780 or the Russians of 1914, who had no idea that the worlds they lived in could degenerate so rapidly into misery and terror” (2008b, 264-5). Thus, it will be particularly interesting to see which threats Yarvin will acknowledge in the rest of the “Clear Pill” as the Real upon which to found his touted new alternative to Progressivism, Constitutionalism and Fascism. Will he concede things to each of these ideologies? Can we imagine a Yarvin who believes in catastrophic climate change, “the great replacement” conspiracy and civic nationalism all at once? That one would not be hard at all to imagine, nor a Yarvin of slavery with UBI, nor a Yarvin that simply repeated everything from between Moldbugs 1-3 all at once. However, it is highly likely that the “new” alternative will simply be another modification on the same basic ingredients of authoritarian capitalism, and it is on this matter that we should draw this essay to a close.

Perhaps the soberest approach to Yarvin/Moldbug would be to contextualise him as but one example on a growing list of specimens of the now obvious American “libertarian-to-alt-right pipeline,” in which one might enrol the Tea Party and a fair slab of the recent US “alt-right” (especially the Hoppe enthusiasts), but also things much older. Perhaps we can find rumours of it first in Thomas Hobbes’s belief that if the monarch of Leviathan is installed to keep the religious factions down then supply and demand will simply make everything work out: “The Value of all things contracted for, is measured by the Appetite of the Contractors: and therefore the just value is that which they be contracted to give” (1651, 208). A number of thinkers including George Dyson (1997, 159) and Philip Ball (2004, 34 & 221) have taken note of this line in Hobbes and consider it possibly the first example of economics represented as an autopoetic system. But, of course, one can only “let the market system work” under the authoritarian conditions that neutralise selfish, violent human brutes into homines oeconomici.

This machine is the “lizardbrain” of liberalism, a reactive Calvinist mess terrified of what men might do if the market were not there to tame them. The libertarian inversion of this, to find the market eternal and the state a parasite, is a marvellous delusion indeed, and one of very recent invention that is belied by the fact that the movement so easily flirts with authoritarianism and even outright Fascism when it gets frightened. The Austrian Economics dons Ludwig Mises and F.A. Hayek were more than happy to shill for both Mussolini’s promise of a “free market stage” and Augusto Pinochet’s brutishness under the belief that at very least a temporary dictatorship to keep out the communists was not an entirely bad idea (Robin 2013). Nonetheless, of course the libertarian refrain always remains that Fascism is a leftist qua collectivist movement. No one wants to be left holding that hot potato any more than the mainstream American libertarian scene is willing to acknowledge the problem that the work of Hoppe keeps on churning out self-titled “fascists” dreaming of playing Pinochet and “physically removing” people.

For instance, in early 2017 there was a great internal furore among American libertarians over the Hoppe Caucus’s invitation of Richard Spencer to the 2017 International Students For Liberty Conference. This ended in a punch up and several of the website Liberty Conservative’s writers being “doxxed” by self-titled “Antifa libertarians” for covering the event (Lucente 2017). In October 2017 in a speech titled “Libertarianism, the Alt-Right and AntiFa” Hoppe responded by simultaneously expressing his disappointment in Spencer’s embrace of “white nationalist socialism” and commending the “alt-right”–in spite of its ideological disorganisation–for its ethnocentrism, belief in natural hierarchy, refusal to be cowed by Antifa, and distrust of academia. As far as Hoppe was concerned, much of the “alt-right” seemed part and parcel with the tradition of American “paleoconservatives” such as Pat Buchanan and thinkers like Moldbug, links with whom he admits have earned him “several honourable mentions” from the SPLC over the years. Moreover, in early 2018, following concerns by the Mises Institute over the white nationalism of an upcoming book titled White, Right and Libertarian, for which Hoppe had agreed to write a foreword, Hoppe retracted the foreword and distanced himself from the author (Rachels 2018).

What can we make of all this? Should we concentrate on the phylum of reaction that is clearly fascism qua hypertrophied authoritarian capitalism and desire to get a better look at its subspecies, we find ourselves caught in a strange triangle of a sort. On one side we have NRx as a Utopian patchwork of shining privatised Neo-Singapores, as Moldbug 1 and Land would seem to desire. On another side by the sort of shiny Google “left fascism” of “woke capital” Land and his minions would obviously abhor. On a third we have good old fashioned, blood-soaked Pinochetian brutalism, Leviathan with its sword raised. In this triangle no single side can be folded into another–each continues to haunt the others. It would be too easy to turn them into a spectrum running Left Fascist-M1-Pinochet in increasingly open brutality, but this would of course obfuscate the “niceness” that the information age society of cybernetic control likes to affect through technological means of repression in order to appear to soften the blow (including futuristic fantasies of VR prisons).

In this we should not pass over the fact, once again, of the plurality of Moldbugs. Moldbug 2 is far closer to Pinochet, as too would Moldbug 3 very likely be. The Landian accelerationist “patchwork” vision of things doesn’t stand a chance in hell of existing because there’s nothing to support its fantasies of secessionism, not even in some tiny imagined gap between the US Empire’s decline and some Neo-Chinese Empire rising. Nonetheless, “left fascism” will certainly have a go at eating the world given half a chance, even if it must beg the existing liberal Leviathan to turn a blind eye, for Leviathan increasingly cannot do without the informatic monopolies of Google and friends to maintain governance. So too, one can never underestimate the possibility that at some point the “libertarian-to-alt-right pipeline” will bring forth something truly nasty, blunt and simple in the manner of a Pinochet in America and that it is only likely that it will lean on a certain sort of cold, cruel Calvinist Christianity in order to support itself.

It is against both of these forces that one would do well to look back over the counter history of “creeping Calvinism” and “Quaker thuggery,” for, in America at least, Christianity still retains the power to build images of alternative worlds, some hellish, some paradisiacal. That the American Left in the second half of the 20th century was so keenly and myopically willing to abandon Christianity as something primitive and irredeemable, fit only for the bigots, is perhaps one of the most politically foolish decisions ever made. Back in the 1960s epochal thinkers like Norman Brown (1959) and Theodor Roszak (1973) understood well that they were the inheritors of the tradition of radical non-conformists like William Blake. This was soon forgotten in efforts to be as far away as possible from anything even vaguely mystical for fear of its commercial recuperation, lifestylism and naïveté.

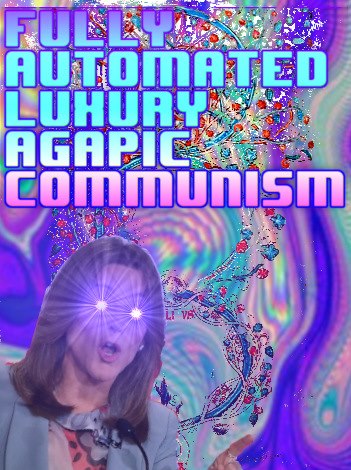

But strangely, this old spectre recently re-appeared again in the online “Orbgang” meme-factory of Democratic presidential candidate Marianne Williamson that managed to unite all sorts of people across political, racial, age, gender and religious spectra (Figure 1, Figure 2). More than any public figure in recent memory Williamson with her message of politics-as-love and Course in Miracles embodies a bizarre distillation of the weirdest aspects of non-conformist Christianity that could only still be cooked up in America. It’s very easy, of course, to put down Williamson as a New Age hack and a joke (though the memes about her are a great deal of fun and we do live in a meme-war economy in these times). But one rarely finds a New Age hack interested in politics, let alone one with practical proposals on matters such as reparations and climate change to the left of just about all of her competitors. Williamson was always very unlikely to get anywhere, and the American Left were particularly cruel to her. But one does wonder whether something very powerful could be done against our age’s overwhelming atmosphere of pessimism, fear, jealousy and bad faith if the powers of both Christian and post-Christian love, harmony and mercy could be harnessed once again for political purposes.

_____

Jonathan Ratcliffe was educated by mad Guénonians, holds a doctorate in Mongolian Studies from the Australian National University, and writes the occasional piece on political theology. He blogs at Mechanical Owl.

_____

Notes

[1] Back in mid-2017 the main page for the Urbit website contained the very Moldbuggian libertarian motto that: “If Bitcoin is money and Ethereum is law, Urbit is land.” This seems to have been removed as part of an overall renovation of the page between then and now–likely following Yarvin’s departure. One should also note Moldbug’s (2010a) old idea of Feudle, a feudal search engine where the trustworthiness of information was controlled by tiers of experts.

[2] Also note that in 2015 Yarvin’s invitation to another conference, Strange Loop, was cancelled. This drew a fair amount of momentary media attention. See Auerbach (2015) in Slate, and, for comparison, Bokhari (2015) in Breitbart on the issue.

[3] Perhaps the most profound difference in vocabulary between Moldbug and Carl Schmitt is that while both of them take the sovereign absolute ruler to be the superior form of government, Schmitt of course regards this as “the political” historically threatened by attempts to neutralise it using religion, technology, metaphysics. In comparison Moldbug (2008b esp. 55, 2010b) is avidly against “politics,” which is what happens once more than a few people are involved in the decision-making process. Moldbug even as a quasi-Platonic scheme of degeneration of a sort. Imperium in imperio (absolute sovereignty of the ruler) passes from the decisionism of a monarch “…to oligarchy, oligarchy to aristocracy, aristocracy to democracy, democracy to mere anarchy” (2010b). Schmitt fears a world without conflict; Moldbug fears chaos.

_____

Works Cited

- Agamben, Giorgio. 2011. The Kingdom and the Glory. Translated by Lorenzo Chiesa and Matteo Mandarini. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

- Anton, Michael. 2019. “Are the Kids Al(t) Right?” Claremont Review of Books (Aug 14).

- Atavisionary. 2018. “Curtis Yarvin (Mencius Moldbug) Backlisted and Banned by Google.” Atavisionary (Jan 9).

- Auerbach, David. 2015. “The Curious Case of Mencius Moldbug.” Slate (Jun 12).

- Ball, Philip. 2001. Critical Mass: How One Thing Leads to Another. London: Arrow Books, Random House.

- Benjamin, Walter. 1940. “On the Concept of History.” Translated by Dennis Redmond.

- Bishirjian, Richard J. 1976. “Carlyle’s Political Religion,” Journal of Politics 38:1. 95-113.

- Bloch, Ernst. 2000 [1923]. The Spirit of Utopia. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

- Bokhari, Allum. 2015. “A Tech Conference that Bans Speakers Must Be Consistent.” Breitbart (Jun 15).

- Brown, Norman. O. 1959. Life Against Death. Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press.

- Carlyle, Thomas. English and Other Critical Essays by Thomas Carlyle. New York: Everyman Library, J. M. Dent and Sons.

- Carlyle, Thomas. 1971. Selected Writings. London: Penguin.

- Charlton, Bruce. 2013. “The Leftism of Mencius Moldbug.” Bruce Charlton’s Notions (Jul 13).

- Cohn, Norman. 1962 [1957]. The Pursuit of the Millennium. London: Mercury Books.

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1994. Difference and Repetition. Translated by Paul Patton. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1983 [1972]. Anti-Oedipus.Translated by Robert Hurley et al. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Dupuy, Jean-Pierre. 2014. Economy and the Future: A Crisis of Faith. Translated by M. B. DeBevoise. East Lansing MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Dyson, George. 1997. Darwin Among the Machines. London and New York: Penguin.

- Gray, John. 2007. Black Mass. London: Penguin Books.

- Hill, Christopher. 1991. The World Turned Upside Down. London: Penguin.

- Hobbes, Thomas. 1651. Leviathan. London: Andrew Crooke.

- Hoppe, Hans Hermann. 2007 [2001]. Democracy: The God That Failed. London and New York: Transaction Publishers.

- Hoppe, Hans Hermann. 2017. “Libertarianism, The Alt-Right and AntiFa,” The Unz Review (Oct 20).

- Kirsch, Jonathan. A History of the End of the World. New York: Harper Collins.

- Land, Nick. 2011. Fanged Noumena: Collected Writings 1987-2007. Falmouth UK: Urbanomic.

- Land, Nick. 2013. The Dark Enlightenment.

- Land, Nick. 2016. “Sore Losers.” Urbanomic.

- Land, Nick. 2017a. “A Quick and Dirty Introduction to Accelerationism.” Jacobite (May 25).

- Land, Nick. 2017b. “The Atomization Trap.” Jacobite (Jun 6).

- Land, Nick. and Heinrichs Palmgren. 2017. “The Dark Enlightenment: Neoreaction and Modernity.” Red Ice Radio (May 15).

- Levy, David. 2000. “150 Years and Still Dismal.” Foundation for Economic Education (Mar 1).

- Lovelock, James. 2007. The Revenge of Gaia. London: Penguin.

- Löwith, Karl. 1949. Meaning in History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lucente, Rocco. 2017. “Antifa ‘Doxxes’ The Liberty Conservative Writers, Hoppe Caucus.” The Liberty Conservative (Mar 1).

- Milbank, John. 2019. “An Offering to Athens.” Jacobite (Jan 29).

- Milbank, John and Adrian Pabst. 2015. The Politics of Virtue. London and New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Matthews, Dylan. 2017a. “Neo-Monarchist Blogger Denies He’s Chatting With Steve Bannon.” Vox (Feb 7).

- Matthews, Dylan. 2017b. “Why the Alt-Right Loves Single-Payer Healthcare.” Vox (Apr 4).

- Mencius [Curtis Yarvin]. 2007a. “A Short History of Ultracalvinism.” Unqualified Reservations (Jun 12).

- Moldbug, Mencius [Curtis Yarvin]. 2007b. “Universalism: Post-War Progressivism as a Christian Sect.” Unqualified Reservations (Jul 17).

- Moldbug, Mencius [Curtis Yarvin]. 2007c. “A Formalist Manifesto.” Unqualified Reservations (Apr 23).

- Moldbug, Mencius [Curtis Yarvin]. 2007d. “Why I Am Not a White Nationalist.” Unqualified Reservations (Nov 22).

- Moldbug, Mencius [Curtis Yarvin]. 2008a. “A Theory of the Ruling Underclass.” Unqualified Reservations (Feb 14).

- Moldbug, Mencius [Curtis Yarvin]. 2008b. “An Open Letter to Open-Minded Progressives. Chapter 1: A Horizon Made of Canvas.” Unqualified Reservations (Apr 17). Complete 14-chapter document also available in PDF on GitHub.

- Moldbug, Mencius [Curtis Yarvin]. 2008c. “Patchwork: A Positive Vision.” Unqualified Reservations (Nov 13).

- Moldbug, Mencius [Curtis Yarvin]. 2009a. “A Gentle Introduction to Unqualified Reservations. Chapter 1: The Red Pill.” Unqualified Reservations (Jan 8).

- Moldbug, Mencius [Curtis Yarvin]. 2009b. “Why Carlyle Matters.” Unqualified Reservations (Jul 16).

- Moldbug, Mencius [Curtis Yarvin]. 2009c. “A Gentle Introduction to Unqualified Reservations. Chapter 10: The Mandate of Heaven.” Unqualified Reservations (Oct 11).

- Moldbug, Mencius [Curtis Yarvin]. 2009d. “A Gentle Introduction to Unqualified Reservations. Chapter 11: The New Structure.” Unqualified Reservations (Nov 19).

- Moldbug, Mencius [Curtis Yarvin]. 2009e. “The Dire Problem and The Virtual Option.” Unqualified Reservations (Nov 12).

- Moldbug, Mencius [Curtis Yarvin]. 2010a. “The Future of Search.” Unqualified Reservations (Mar 11).

- Moldbug, Mencius [Curtis Yarvin]. 2010b. “Divine Right Monarchy for the Modern Secular Intellectual.” Unqualified Reservations (Mar 18).

- Moldbug, Mencius [Curtis Yarvin]. 2013. “The Greatness of Lawrence Auster.” Unqualified Reservations (Feb 19).

- Moldbug, Mencius [Curtis Yarvin]. 2016. “Coda.” Unqualified Reservations (Apr 16).

- Nostalgebraist. 2016. “NAB Notes: Moldbug and Counter-Revolution.” Trees Are Harlequins, Words Are Harlequins (May 10).

- Noys, Benjamin. 2014. Malign Velocities: Accelerationism and Capitalism. Winchester UK: Zero Books.

- Osterweil, Vicky. 2017. “Liberalism is Dead.” The New Inquiry (Sep 15).

- Phillips, Leigh, and Michal Rozworski. 2019. The People’s Republic of Walmart: How the World’s Biggest Corporations are Laying the Foundation for Socialism. London and New York: Verso.

- Piketty, Thomas. 2018. “Brahmin Left vs Merchant Right: Rising Inequality & the Changing Structure of Political Conflict (Evidence from France, Britain and the US, 1948-2017).” WID.world WORKING PAPER SERIES N° 2018/7 (Mar).

- Pickstock, Catherine. 2013. Repetition and Identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rachels, Chase. 2018. “Clearing Up the Hoppe Foreword Controversy.” Radical Capitalist (Jan 25).

- Ratcliffe, Jonathan. 2018a. “Political Theology in the 21st Century 4: The Return of the King,” Mechanical Owl (Apr 1).

- Ratcliffe, Jonathan. 2018b. “Reactionary Voegelin and the Coming of the Basilisk.” Mechanical Owl (Apr 1).

- Reynolds, Simon. 2009 [2000]. “Renegade Academia: The Cybernetic Culture Research Unit.” Energy Flash (Nov 3).

- Robin, Corey. 2013. “The Hayek-Pinochet Connection–A Second Reply to My Critics.” Crooked Timber (Jun 25).

- Roszak, Theodor. 1973. The Making of a Counter Culture. London: Faber and Faber.

- Rothbard, Murray N. 1989 “World War I as Fulfillment: Power and the Intellectuals,” Journal of Libertarian Studies 9:1.

- Sandifer, Elizabeth. 2017. Neoreaction, A Basilisk: Essays on and around the Alt-Right. Ithaca NY: Eruditorum Press. eBook.

- Schmitt, Carl. 2005 [1923]. Political Theology. Translated by George Schwab. Chicago and London: Chicago University Press.

- Schmitt, Carl. 2009 [1956]. Hamlet or Hecuba. Translated by Dan Pan and Jennifer R. Rust. New York: Telos Press.

- Spengler, Oswald. 1926. The Decline of the West. 2 Vols. New York: Alfred A. Knopf Publishers.

- Tawney, R. H. 1948. Religion and the Rise of Capitalism. London: John Murray.

- Thiel, Peter with Brian Masters. Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future. London: Virgin Books.

- Towsend, Tess. “Controversy Rages Over ‘Proslavery’ Tech Speaker Curtis Yarvin.” Inc (Mar 31).

- Voegelin, Eric. 2000a. The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin Vol. V: Modernity Without Restraint. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- Voegelin, Eric. 2000b. The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin, Vol 11: Published Essays, 1953-65. Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press.

- Weber, Max. 1976 [1930]. The Protestant Work Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Anthony Giddens. London: Allen and Unwin.

- Yarvin, Curtis. 2016a. “Why You Should Come to LambdaConf Anyway.” Medium (Mar 26).

- Yarvin, Curtis. 2016b. “I’m Curtis Yarvin, Developer of Urbit. AMA.” Reddit (Mar 25).

- Yarvin, Curtis. 2019a. “A Founder’s Farewell.” Urbit.

- Yarvin, Curtis. 2019b. “The Clear Pill, Part 1 of 5: The Four-Stroke Regime.” The American Mind (Sep 27).

- Yarvin, Curtis. 2019c. “The Clear Pill, Part 2 of 5: A Theory of Pervasive Error.” The American Mind (Nov 25).

- Yarvin, Curtis. 2020. “The Missionary Virus.” The American Mind (Feb 1).

- Žižek, Slavoj and Boris Gunjevic. 2012. God in Pain: Inversions of Apocalypse. New York: Seven Stories Press.