This essay is published as part of the b2o Review’s “Stop the Right” dossier.

The Way-Out-There Right: The Claremont Institute

Paul Bové

How the American Right has gone about ordering a new political hegemony in the US is an important if no longer an interesting question. Counter-revolutionary movements follow a recognizable path with few essential differences despite the newer tools available to later movements: from pamphlets and sermons, newspapers, mobs, crowds, radio, and other acoustic devices, up to now digital technology. Right-wing movements study history to find tactics that ease their way to power. Not surprisingly, they also study the mechanisms of left-wing revolutions finding, for example, in Lenin both a historically proximate example and a written record of strategies and tactics for clearing the terrain of competitors for power by defeating those that resist. The intellectuals of the contemporary American Right study Antonio Gramsci, whose careful analyses of fascism’s socio-economic foundations show the Right how to prepare the ground, the socio-economic culture of a nation, to make it available for seizure and control. Along with Lenin, Gramsci’s thinking shows on which points in the society that it intends to overthrow the counter-revolution should focus its attacks.

In earlier Rightist intellectuals’ work, the new American Right finds accommodating mediations to understand its own situation, locate a needed familiar, that is, the political-historical justification of its desires, and perhaps most important learn how to fracture the society it wants to seize. While Leo Strauss is a significant resource with broad influence on the Right, Carl Schmitt’s thinking matters more in practical terms for the Right and more reveals its aims for the rest of us. Especially since George W. Bush launched a war on terror to protect the newly conjured “homeland,” American academic humanists especially, following European writers such as Giorgio Agamben emphasized Schmitt’s persistent discussion of the state of exception for its explanatory power and supposed political affect against (liberal) state action as a sovereign force outside constitution and Law. The Claremont Institute, however, finds more value in Schmitt’s creation of the “partisan” as a necessary figure to strike against the state and then to hold it. Schmitt in Claremont’s doings projects a handbook of tactics, intent, and theory for the violent breaking of a society to seize power as the sole alternative to what its visionary fever propagandizes as chaos and anarchy.[1]

The Claremont Institute is home to much of the Right’s intellectual provisioning, including mythologies of national fall from innocence, the necessity of recovery, and the requirement that inherited carnage requires curative treatment by a post-democratic, extra-constitutional Caesar, established with impunity and plenary power.[2] I assemble Claremont’s poses and facades to see it and call it by its proper name to place before us the Right’s most basic motives, intents, and desires. If you will, this little essay is an exercise in summoning out and displaying an active but deeply shadowed will.[3]

The political Right in the US has an expansive, fluid, well-funded, and varied system of both digital and analog institutions that generate propaganda, intrude in news cycles, and develop theories of state power and tactics for its control. A few examples give some sense of this structure’s variety and influence: Stormfront publishes and endorses what to many seems to be hate speech; the Heritage Foundation intends to overturn the Madisonian system of power balancing to concentrate unchecked power in the Executive; and the Claremont Institute supports and advances intellectual and tactical politics that justify and enable a post-democratic American state led by a historically necessary Caesar.

Claremont has a lower public profile than other nodes in the Right’s ecosystem, and its façade hides its beliefs, procedures, and goals. Claremont effectively transforms the Right’s desires into high ideas and provides national narratives through which a massed political cohort sees US history and its present moment. Also, Claremont trains its agents—interns, fellows, and willing allies—in the intellectual discourse organic to the political Right’s desires, self-understanding, and political aims. It produces a thorough and saturating double-speak of an aspirant nationalism that would destroy the American constitutional republic to redeem what it dishonestly calls the lost origin of the American Nation. Claremont is something like a seminary for training priests or a Lukáscian vanguard, releasing mostly young men into the political ecosystem prepared rhetorically and ideologically to destroy the given, to redeem lost innocence. In toto, Claremont is both an instrument for the tyrannical seizure of power and a principal element in that seizure’s masking. It calls, as an instance, for a Caesarist post-democratic sovereign order in the guise of putatively restoring the ideals of the Declaration of Independence’s anti-monarchical politics. It thrives in comedy for tyrannical purposes.

Claremont invites serious examination on its own terms. Intellectuals must resist this siren’s call.[4] Claremont defines its own intellectual origins in the writings of Leo Strauss and his ephebes. The invitation to study Claremont to expose its heritage plays Claremont’s game, which is multi-faceted and monumental, far less in need of explication that bothers with its “depths” than with description or naming that show what it is in its motives and desires. These last we can name if we resist the urge to examine Claremont in the complex terms with which it explicitly masks itself.

Extended scholarly study of the Claremont Institute will add layers to the markings that hide the Institute’s threats to humanity, democracy, freedom, and creativity. Interpretive processes and misplaced curiosities that layer their expositions to understand Claremont make it seem complex and interesting, at best deferring its danger to continue to study its background, origins, and alignments; at worst, erroneously to deny those threats. Learned and cautious readers will hesitate to assent to the fact that Claremont threatens in these terms, deflecting the charge as exaggerating or misreading the status and effect of what is, after all, a “think tank” that publishes book reviews, holds conferences, and funds interns albeit in right-wing political rhetoric. For the hesitant, Claremont is the kind of serious intellectual diversity that liberally biased universities suppress or misunderstand. For the hesitant, then, conversation or dialogue, respectful exchange seems the best course to understanding Claremont and to the display and benefit of greater virtuous tolerance. Scholars might hesitate to declare Claremont a threat in my terms unless and until fuller scientific research provides adequate evidence to characterize the Institute. Those who refuse (yet) to accept that Claremont does, indeed, threaten in these ways typify the mind-set and political behavior on which Claremont relies to defeat those who, deferring judgment, become inactive or so slow as to be already belated. Claremont understands such deferral and hesitancy as a given, inherent political weakness on the part of its enemies, as not only the disablement of criticism, but more important in democratic republican politics as fleeing political struggle rather than making sacrifices in partisan combat.

How then are we to know Claremont? Primarily by its actions especially as they link these to the purposive actionable motives of their writings and statements. We must read their motives, their will’s formations, and the strategies exposed in their tactics. For all this, reading them in themselves is essential with the help of excellent journalism. Or we might take another approach. Claremont’s and the American Right’s invocations of the so-called classical writings of the Eastern Mediterranean as sources of proper philosophy entitle us to recall Socrates’ encounter with Callicles to see Claremont’s attraction to physis and sophistry as a world-view and rhetorical practice with worrying political consequences, even for the non-democratic Plato. As Callicles turns away from Socratic criticism, refusing to defend rationally his own selfish claims to advantage the stronger in society, so Claremont rests immovably in its ideological commitments to Caesarism, limited liberty, and rule by the strong men who win and tightly hold power. Along the way, like Callicles, they show no concern with justice, truth, and language. Like Callicles, one of their predecessors, they use rhetoric to achieve their goal of rule by natural superiority and, presumably, its satisfied pleasures.

The once mainstream newspapers report on the institute’s existence, its political alignments, and more rarely on its history or its funding sources, which Claremont obscures. Journalists mostly report on the façade not as such but with occasional interest in what putatively lies behind it. Taking the façade seriously would be productive good journalism, but, reports on Claremont’s connection to powerful politicians such as Vice-President JD Vance, whom the Institute celebrates as a favorite son, go almost nowhere.[5] The institute influences policy and political action, especially in legal theory, often with the support of prominent political actors. Claremont stresses its own commitment to litigation to restore what it calls the Founding after its distortion by democratic-republican politics.

The litigation it promotes or supports is tactical; it often targets two elements in law. First, something the media will accept as at once important to what Claremont’s liberal enemies consider vital (a paper like The New York Times serving a large part of its audience), but second by undercutting the political legal formations upon which a democratic republic can exist. Following Schmitt to the letter, Claremont politicizes the legitimacy of law and of established institutional, constitutional arrangements both to encourage a mass cohort’s oppositional identity and to leave everything up for grabs by the organized and well-prepared Right that desires the sort of violent litigation Claremont encourages.

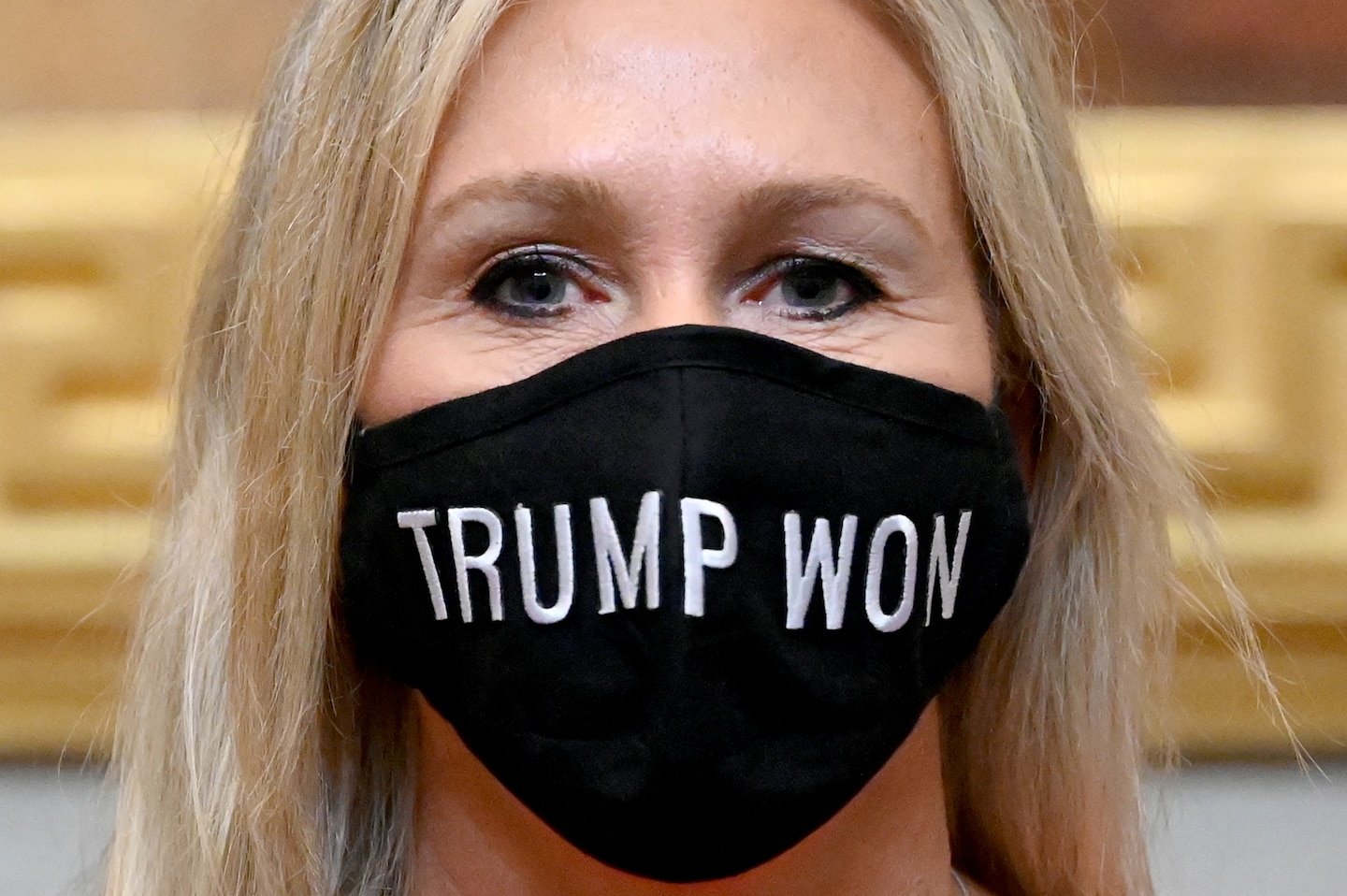

When, for example, the federal government ordered an end to the practice, long set up in constitutional law of recognizing people born in the United States as citizens, The New York Times traced the government’s legal theory that justifies repealing the law and customary historical expectation to the now legally suspended California attorney John Eastman, a member of the Claremont Board.[6] The Times is not alone in noting Eastman’s association with Claremont and as the “idea man” behind the Right’s efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election. As part of daily political and legal news, Claremont sits next to matters of ordinary state business.

Readers and viewers of written and visual news media became a little acquainted in various contexts with the Institute’s existence, its alignments, as a source of new thinking, often generated to the needs of its political allies. Like any such school for ideas, Claremont must circulate its own controlled news of itself and it does so always, sometime in print media, but regularly and widely on social media and, crucially in the case of Claremont, through its own text-based media—The Claremont Review on printed paper—and The American Mind, an online publication of the Claremont Institute attending, as the editors put it, “To the ideas that drive our political life.”

Through these instruments and in response to curious requests for information and in interviews with its leading figures, The Claremont Institute tells stories of its own origins. In most versions, the Institute (1979) results from the simple efforts of a small group of ephebes, doctoral students of Harry V. Jaffa, under the influence of Leo Strauss. Claremont’s institutional existence started in a small propaganda project, called Public Research Syndicate, which flooded newspapers with conservative Op Eds. The Institute received generous seed funding from the NEH (Directors William Bennett and Lynne Cheney) during the Reagan administration and ever since from rightist oligarchs. Claremont has developed institutional affiliations and substantial ideological connections with and for allies among fellow travelers especially in intellectual and higher education circles. One thinks of Hillsdale College and Notre Dame University as examples of different sorts of alignment. With allied people and institutions, Claremont supports smaller ideological centers to house its offspring and their efforts, embody its influences, stabilize its projects, and enhance its prestige. For example, one of Claremont’s and the new Right’s leading figures, Michael Anton, both a fellow of the Claremont Institute and a member of government, became, when out of office, a research fellow at Hillsdale College’s Kirby Center in DC.[7] An ever-noisy Claremont never states the aims, effects, and desires behind its actions and maneuvers. To come near to the secrets not told, one must first see, describe, and warn of the projects, intentions, and consequences already set up and in motion.

Public discussion links Claremont to a generalized Rightist politics that media and scholars too often call conservative or authoritarian. Journalism often calls the Institute a “think tank.” There are two errors in all this and both result from not calling a thing by its right name. In the spirit of Claremont’s often pretentious adoption of Shakespeare’s texts, let me say that his Juliet is wrong when she says a rose by any other name is just as sweet.[8] Tragedy teaches us she is wrong. Juliet is a child, grown only enough to feel romantic love and sexual attraction. “Tis but thy name that is my enemy,” she says to the night. She loves a Montague, which means as she knows that she has, in best Aristophanic fashion, found that part of her once cut away by jealousy and force. That cut away part has in history become her founding enemy; “Montague” is the ring fence limiting her possibility as agent and dreamer: “O, be some other name,” she demands. He must have another name improper to him and outside the essential inescapable relationship between them, namely, enmity. Romeo will be “new baptized” and left nameless: “I know not how to tell thee who I am. / My name, dear saint, is hateful to myself / Because it is an enemy to thee.” Yet, despite this and her earlier desire to detach proper name from an identity that has made her Juliet, she cannot escape: “I know the sound. / Are thou not Romeo, and a Montague?” Juliet’s efforts not to call Romeo by his name stabilize a tragic form. What does it do? How does it work? She cannot transform a murderous enemy by love. She cannot change force and historical burden by renaming, or worse, by ignoring all that which the inescapable name arrests and predicts. Her enemy draws her into a desire for a reality that mirrors her wish, that the enemy were like her, were part of her, were not the poison that would lead her to extinction. All these results come from not calling a thing by its proper name, believing renaming is a transformative power while all it does is misprise the situation, the state of power, and the enemy. Such misprision, feeling itself to be love, does not despise or undervalue except ultimately. It devalues the grasp of established power, and it undervalues threats in what she hopes to pacify or nurture by transforming the dehumanizing threat found precisely in the proper name. Long ago, we learned the proper name owns, but not that changing the name does no more than mask a reality the aspirant or lover cannot confront, defeat, a call to use its proper name. Baptism or rebaptizing deludes. Priests do not have the power to escape or transform what they would rebaptize—a superfluous, secondary, inert ritual—and together with their followers, they capitulate.

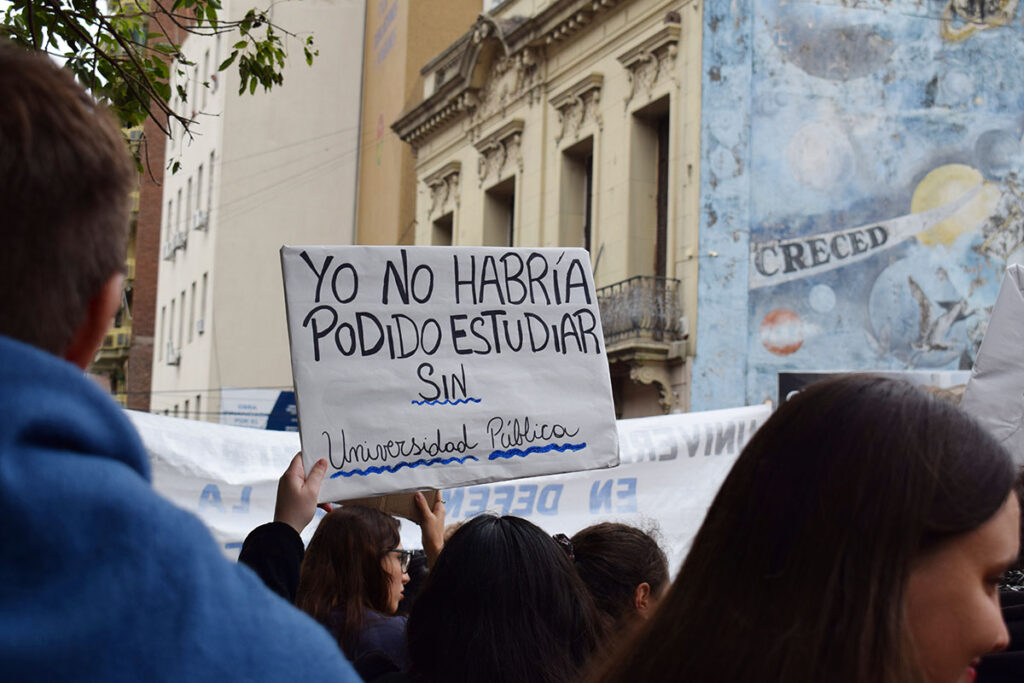

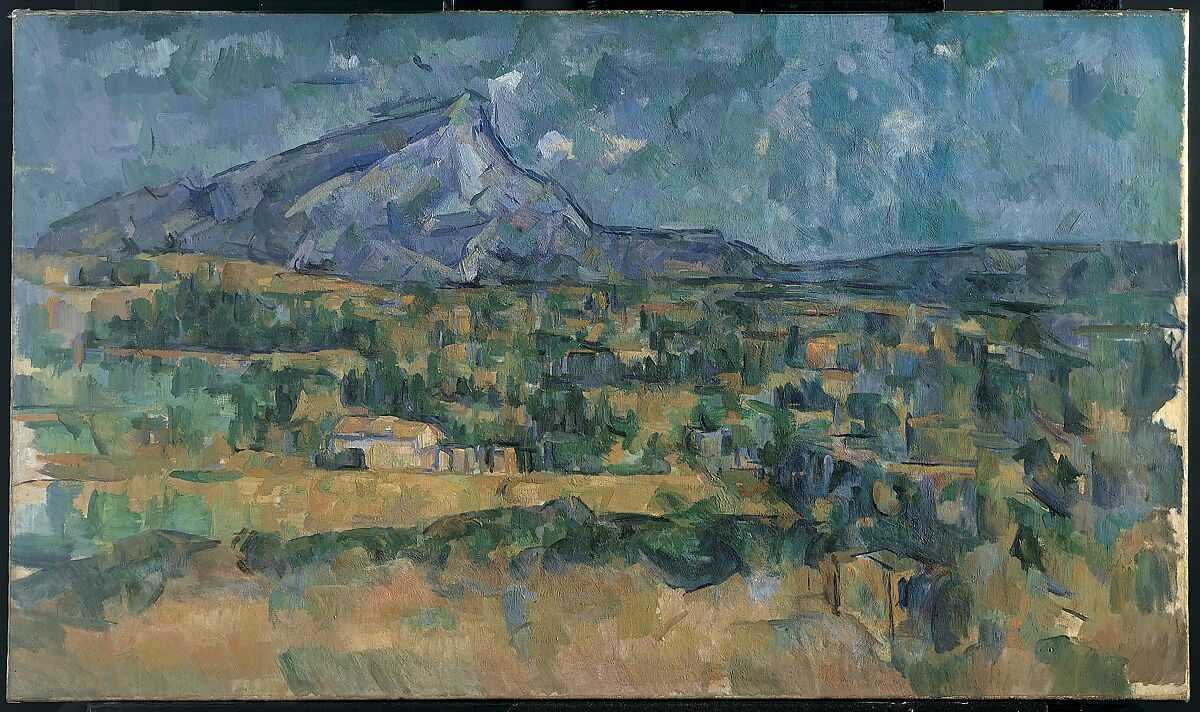

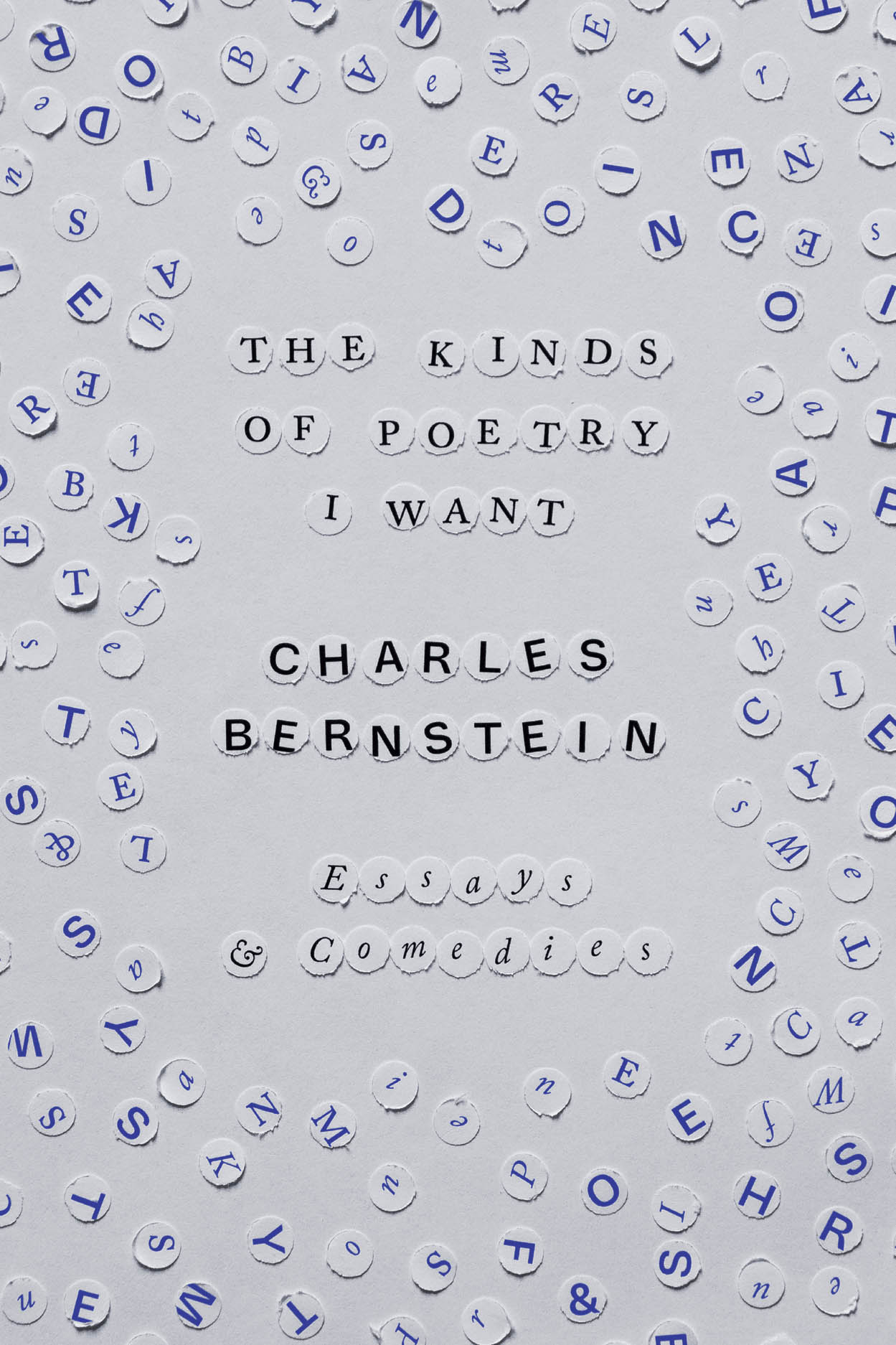

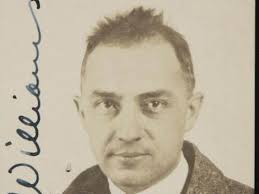

Take Confucius as an example: call things by their proper names. Poets and critical writers insist on calling things by their proper names. “No ideas but in things” means things come before the names that ideas might provide for what they are. Names might even gesture towards the ideas or partially derive from them. Only a naïf, a selfish, a fearful or desiring critic believes they can change the thing with a word that flows like a tertiary effluent. History is replete with the inhuman consequences of this error, from early modern horrors of the Code Noir (1685) to the ongoing debasement of “aliens” who infect “our blood” (2023). Only the applied power of violence and money enforce these names against that which has lost its name. Shakespeare’s dawn song vignette unsettles the cliché popular and medium-brow culture derive from it. Claremont is not a “think tank” any more than it serves an authoritarian or conservative politics. Claremont is secretive, well-established, and influential. It may shade itself on the horizon, which means lights of distinct colors cast on it let it appear not each time “differently” but each time additively so that gradually the thing itself appears. To Rightists it might appear as the green ray. Critical reflection on a center of counter-revolutionary planning and training needs a poetic artistry, like a Cézanne patiently, actively, persistently intends to make a mountain and light itself seen. A mountain by any other name is not just as monumental. A secular critical mind does not bother with Claremont in a study of think tanks, of civil society institutions, of academies for conservative thought. Such studies, whether disinterested or not, whether detached and professional or angry and aggressive, oddly enough are less creative, less poetic than Claremont itself whose raison d’être is the creation of a new culture upon the rubble, after the carnage, of battering down the walls of its enemies’ bastions and institutions. In the end, all of that is to make sure “enemies” cannot return and that Claremont’s vision defines all life practices on the fields of social and cultural poiesis.

How dangerous is this? Consider its antagonism not only to its racial, class, and ethnic enemies and the forms that gathered standing with them, but also its extermination of imaginations like Cézanne’s whose analyses made light an instrument of seeing, and of poets like William Carlos Williams who in the movements of time made life still for knowing and feeling. Cézanne or Williams were analytic and geometric—to uncover what names obscure and empower—so that their still lives would make new relations between forms, words, and things available for use, feeling, and repetition—for the freedom of poetic liberty. No ideas but in things, becomes with them no ideas but in poiesis. There are good and evil even in the working out of poetics. Confucius teaches that the only route to wisdom is to call things by their proper name. Claremont would decide and delimit who can name or have the power to make a name proper, that is, settled and all-embracing. If only one can name then there is no freedom, but only slavish incapacity in the face or grasp or trance of things. (Perhaps Orwell is a dystopian Claremont has studied.) The critic who opposes this usurpation of freedom must at least call by its proper name the agent of tyranny that will project its own, enduring unreformed sublime monumentality which might be called King, Caesar, or tyrant.

The Claremont Institute has a geometry and the same sort of stable being in place as any mountain or wheelbarrow, even if Claremont is not yet called St. Victoire. And so, we can dissolve and rearrange its forces, pressures, and fissures. Balance gives it a normal place on a regular terrain of institutions, ambitions, and ideas. To see it, let ideas come from what it is, not what it says it is. Its founders made it normal and indistinct, inconspicuous. Cézanne worked with his mountain repeatedly over years because it had value as his art. Hardly inconspicuous, it was a settled regional monument, always well-known and unseen by cohabitants. Is it an illusion to think the same is true of Claremont? For a journalist or political writer, Claremont, well-financed, secretive, and intellectual, is part of the landscape, lodged in a suburb, withdrawn from view. Yet, knowing its actions and intents, it tempts, as the mountain must have tempted Cézanne to reassemble its fixed status, to explore its constituents. It is there inviting the exercise of the suspicious critical mind. In a Disney-fied Meta worldscape.

Established hermeneutics and philological procedures let investigators study Claremont along two lines. First, the standard practice and ideological claim of historicists who study, map, and understand the contexts in which an object exists, words work, or nations extend themselves, make history expanding contexts, generating horizontal or adjacent relations along flows of power and interest as a field of reading. We now call this the “cultural text.” Claremont might call it the geopolitical or the new Imperium. Second, ahistorical hermeneutics, formalists, or allegorists, by attending to appearance, generate the conditions for genealogical questions, for forms of study that answer the question, how did it come to be? Nietzsche and Foucault are exemplary of this method. The thing is not ahistoricality as such, but the result of expressly nonlinear entanglements of will, desire, and often anonymous transformative forces.

The much-admired German-American musicologist, Christoph Wolff, a renowned scholar of Johann Sebastian Bach, formulates in less than a paragraph the felt necessity of contextual location as essential to a serious understanding of Bach. At first, Wolff’s statement of intent, desire, and necessity is straightforward and enabling: “In the case of a painter, poet, or musician, the primary interest focuses, without a doubt, on the works of and their aesthetic power, but a deeper understanding of works of art presupposes also a special awareness of their historical context” (8).

Such a normative approach to Claremont could interest readers, citizens, and politicians. Too often, however, historicism turns intelligence from the object or thing, the study of which in this manner turns the mind elsewhere and away. Contrast this to Cézanne’s unrelenting focus on the mountain’s light. Simple paraphrases of Claremont’s self-explanatory and self-justifying stories entice minds toward Leo Strauss and Harry Jaffa to highlight the intellectual ground of its ideology in action. Historicists, unsatisfied, will then question Claremont’s account and place it in relation both to contemporary sympathetic institutions and to predecessors with differing rhetorics and political nuance. What about Burke or Berkeley? What of the John Birch Society or the Southern Baptist Conference? Or the Opus Dei elements among Catholic reactionaries and traditionalists? And, finally, of what value are the answers to such questions and the endless debates they enable that then follow on to and encircle them? At the end, readers know a great deal around and about Claremont, but that knowledge is merely accretion upon a stable and still obscure part of Rightist politics that becomes increasingly monumental and eventually like the mountain is simply there, unseen. To describe Claremont or to refer to it as journalists sometimes do as an intellectual hotbed of conservative thought and aspirations polishes the stone façade of its facticity as a geopolitical, legal, and sociocultural agent in the landscape. And so, it becomes a mirror reflecting others back in their accounts. Claremont has succeeded in a task Lucifer could not carry out: To transform a place where the fallen and excluded could assemble, hatch a plot, act in revisionism and revulsion to promote resentment, or more precisely, ressentiment, on the expressive effect of which its creative power and destructive influence rest.

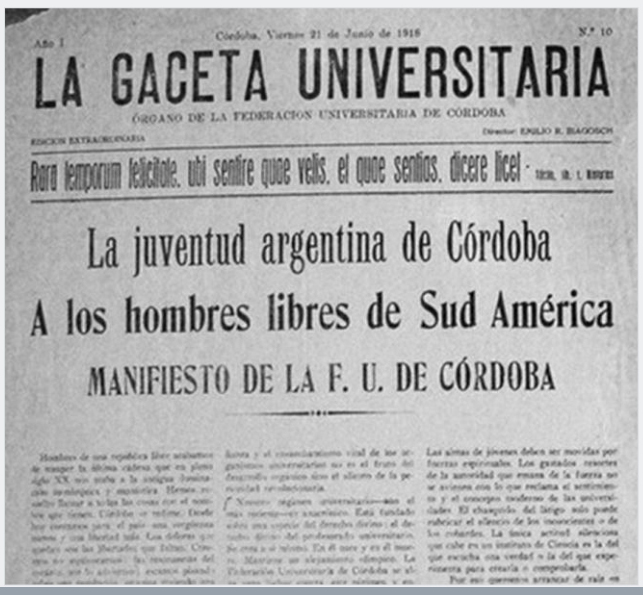

We can say simple and plain things about Claremont. It develops narratives along two lines. As a normal counter revolutionary tactic it puts in place, naturalizes, a grand narrative of national decline from ambitions expressed and set in motion at what Claremont regards and repeatedly calls the “founding.” In US terms, this means Claremont tells stories about the US as if the nation were something that had an origin from which it sprang rather than the immensely complicated entity with diverging histories of a kind and number one could expect of a continental political entity that never at any time in its history existed as a nation-state that like Spain or France set an organic relation between ethnic and linguistic unity and state institutions. As far as those relations came to exist, violence and often extermination played a role (1209, 1492). Making the US into something with a sacralized origin, what Claremont calls the founding, is the first step in Claremont’s contribution to the counter-revolution against secular liberal developments since 1688. Claremont’s most important ideological contribution to the Rightist cause is a secular version of the myth of the fall. The institute sets in place the linear narrative of a fallen origin that sets the stage for a counter revolutionary recovery of something that never existed outside this story. In simple terms, Claremont’s narrative sets out from a counterfeited version of Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence filtered through Straussian orthodoxy. For the Right, the Declaration renews classical beliefs in natural right. From this pure high point, itself a recovery—and therefore from the first a counter-revolutionary document—Claremont’s story makes the US an inherently Rightist entity. From this simple and pure original and yet recuperative impulse Claremont would create a new world and make of Americans a set of new Adams. Conventionally, of course, the Founding, like the Garden of Eden begins a secular story of a fall into the sinfulness of liberalism. In this reading, the Declaration is a messianic document for a new world that liberal politics shattered and weakened with relativism, theories of civil and human rights, and stories that desacralized the origin and substituted stories of complex historical beginnings. The unity of the origin and its Founding impulse was decimated and dispersed. The origin became political and originally human. To recover the messianic counter-revolution of the Declaration requires a new counter-revolution.

The Right adopts Claremont’s fantasy of origins as a mask for the simple evil corruption of the tyrannical seizure of power to set up a Caesar as an extra-legal, post-constitutional sovereign in what had seemed the democratic republic of the US. As Claremont’s story develops, the 1776 origin affirmed administratively in the Constitution of 1787 fell into a secular historical world of struggles, crosscurrents, battles over right and wrong, and most important, a protracted process to suppress the aspirant tyrannical right. In Claremont’s propagandized fantasy, the purity of the origin, lost in and to a history called “liberalism” justifies restoring a tyranny the Declaration only seems to reject. This is a wonderful instance of Claremont’s remarkable Calliclean sophistry: the “founders” justified their rebellion against monarchical tyranny, which was in fact a revolution against the settlements of 1688, with an appeal to natural rights. After liberalism undermines the restorative origin, dirties its purity, then, now only a tyrant, a Caesar can reclaim the origins’ legitimacy justifying not only the destruction of historically organized society but the seizure of plenary power with impunity. Why? As the natural and needed sovereign form available for a return, the necessity of which from atop and out of the origins’ ruins leaves no choice but to reclaim its own power as the origin.[9]

Claremont logically advances the claim that Caesarism is the only political form based on and capable of sustaining a recovered natural right politics. As it set up, codified, and put into action the principles of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution betrayed the origin, created the condition for administration that masks power in law and regulation and over-throws the very founding of America as the return of classical and biblical ideals. In telling this story, Claremont helps create the mass cohort essential to seizing electoral power and in so doing, by alignment with power, to erase from practice, common sense, and memory competing stories of the American nation discrediting other stories that might interrupt its own identity with sovereign power. With feverish purpose it mocks the story, advanced in part by the New York Times, that the US began in 1619, the year enslaved Africans arrived in the US.

For Claremont, the innocence of 1776 dissipated with ever increasing centralization of power, expansion of state administration, and a politics that restricted or regulated freedom that conflicted with natural rights by placing liberty and sovereignty in a controlling state. To authorize itself, Claremont finds resistance to this development throughout national politics, in figures such as Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln whom “liberals” see as antagonists in the conflict of different political ideals put into action. Claremont intends its own story as a disruption of consensus, an end to struggle, and thus a replacement of political common sense. Harry V. Jaffa saw Lincoln as a Straussian hero, antagonistic not only to the liberal sentiments that began to seize power after 1776, but those of 1688 and earlier. In that antagonism, Lincoln, as his contemporary antagonists insisted, according to Jaffa, had become Caesarist and had broken the balancing order of the state Madison established. In an emergency, he not only stepped beyond the law, but over it when, for example, he ignored the Supreme Court’s order to grant habeas corpus to Confederate sympathizers and separatists. Most important, however, Lincoln, a minority president, made the rhetorical claim that national sovereignty rested in the people and upon that authority conducted the war and militarized the socio-economic fabric of the United States.

Often Claremont draws on the ancient texts of the eastern Mediterranean searching, as did Strauss, for authoritative grounds for its worldview. Claremont’s desires lie behind its claimed discovery of the proper world view upon which, putatively, lie its sophistic and self-interested claims to find the desired world view in the US “origin.” Only the decay of such origins, which leave Americans with carnage, justifies its seizure of power, which would end the persistent, if episodic, struggle of certain leaders and movements against liberalism by for the last time monopolizing power under the sign of rebirth. In a purely secular sense, American history—barring moments of Jacksonian resistance—is a record of sin against a recovered origin. The permanent recovery of that origin requires means necessary to end opposition to its regulative power.

In other words, to anyone who has even the most basic grasp of western story-telling—an art Claremont claims for itself—the Institute’s basic repertoire is grossly familiar: identify an origin, a point of innocence capable of projecting force and motive both affiliatively and expansively. In the all too tired but effective instrumentalization of primal fears, needs, and ambitions, sin in the form of a liberal politics masks and sustains the violence of tyranny in an administrative state that surveils the people’s sovereignty that Lincoln invoked and followed to defeat slavery and sustain the Union. In other words, Claremont makes operational in a secular society an unsophisticated, fully cynical version of the Myth of the Fall, which Christians should recognize and readers might know, in more intelligent and liberatory fashion in such paragons of Western Civilization as Dante and Milton. To prefer Jaffa to these names should alone disqualify Claremont for poor judgment, ignorance, and mere sophistry.

In the American electoral system of 2024, the narrative of the fall produced a paradox: a reactionary anti-elitist elite that had manufactured a mass cohort of voters seized power to disassemble the democratic republic, and remake politics to permanently keep power. In the counter revolution, the raw power of the police state forces cultural change across the spectrum of human life. A cadre of leading figures institutionalizes themselves and their heirs—and here we return to the affiliative nature of the origin in the Claremont stories—, because fulfilling the Counter-Revolution requires a permanent seizure of power, to make monumental its inaccessibility to competitors. Journalists, intellectuals, and politicians bemoan the Right’s desires and actions to fulfill its “authoritarian” or “anti-democratic” ambitions. Too rarely do they call it tyranny, or, to use Claremont’s own preferred proper and public term, Caesarism.

“A fallen world requires redemption,” at least, common religio-political myths say as much. From this narrative comes millennial thinking, utopists, apocalyptics, and accelerationists. Claremont’s leading figures embrace various forms of millenarian necessity that Plato condemned as a tragedy. Since Claremont routinely claims it rests on Classical Greek thinking, remembering Plato points to what Claremont well knows, the falsity of its classical beliefs and the bullshit justifications of its hegemonic aspirations of its own stories.

A star among Claremont’s peculiar progeny is Michael Anton. He is the Jack Roth Senior Fellow in American Politics at Claremont Institute. He took master’s degrees in liberal arts from St John’s College, in Annapolis and did advanced study in Claremont Graduate Universities. He worked on Wall Street for Blackrock and Citigroup, and he has served during both of President Trump’s administrations. In September 2025, he stepped down from his position as Director of Policy planning at the State Department, a position first held by George Kennan.

For all its own disposition to practice ideology in language and print, Claremonters carry their message throughout the social media networks of Rightist public politics. The New Founding Podcast (10.3k subscribers) hosts “The Matthew Peterson Show: Conversation,” the first episode of which Anton helped launch as the de facto center of an explanation for the historical necessity of Caesarism. As an emergent higher form of sovereignty rising from the simple rules of post democratic and post constitutional governmental ruins, Caesarism’s establishment will require new stories for its advocates to sell it as the needed “the New Founding.” The videocast named as a site to host propagandists for this idea has lost financial support, not in 2025 an especially important fact. More to the point was Anton’s extended defense of Caesarism launching this site in the early 2020s. A simple search of online sites and traditional news outlets clarifies Anton’s interest in Caesarism, even as a state official, who had sworn loyalty to the constitution of a democratic republic.[10]

For all of Claremont’s pretension to high intellect, its stock in trade is propaganda in two forms. First, its leaders, fellows, and adjuncts use Claremont’s story of the American Fall to encourage and justify actions that only the most extreme crises in civilizational collapses can justify. Claremont’s project had an immense success in President Trump’s first inaugural in which speech writers reduce the Claremont mythography of the Fall to the low mimetic mode in one now famous and effective meme: “This American carnage stops right here and right now.” Journalists and electoral opponents objected that America in 2017 was not a scene of carnage. In offering evidence to prove the President’s statement “wrong”—GDP numbers, data from crime reports—they showed, on the contrary, that they not only misunderstood the President’s statement but the politics it stood for and aimed to impose. Considering Claremont’s public statements and those of its ephebes like Anton, “carnage” signifies three things: first, it declares that the conditions for counter-revolution exist; second, that counter-revolutionaries can openly display their intent to seize state power; and most important, that their intent is to instrumentalize state power for their interests alone. Note that before the word “carnage” comes a Claremontian meme, standing for its project to define the “founding” as an “origin” that calls for its own redemption. Before “carnage” comes the anodyne sounding declaration that “We, the citizens of America, are now joined in a great national effort to rebuild our country and to restore the promise for all our people.” How can a world of carnage not demand redemption? Indeed, as always, redemption requires its own violence, its own carnage. What more effective way to find a just violence than in the verbal echoes of the original violence against liberal England in the name of natural law? Jefferson’s messianism that invoked a universal equality among men gives way to the first inaugural’s emphasis on citizenship as the qualifier to decide the political fate of “all our people.” And here that “our” is not anodyne because of its fully possessive force—all the people of we, the citizens of America. This points to an essential part of the Right’s politics and tactics as advanced especially by Claremont. The citizens of the first inaugural of 2017 have no interest in the universality of ineluctable rights nor, it becomes clear by 2025, in the cohort or partisan mass it gathered for electoral victory.

The president’s speechwriter meant carnage metaphorically, referring to social decay, political disorder, moral disruption. In its sophism, carnage conveys images of disorder, ruination, or devastation. In this conjuring, carnage comes from violence, the stopping of which requires, of course, counter-violence, the direct application of the state’s defining monopoly on violence, political power in extremis deployed to effect the shaping of citizenry and carry out its desires. A new carnage destroys to save—an exhibit of long-standing US power politics, and in this way familiar from revolution to displacement, mass kidnapping, and enslavement, including economic war-making to show power in a unified state.

In an explicit preemptive echo of Lincoln’s account of his authority as a derivative of the sovereign people, the executive in 2017 calls on “we the citizens” as the sovereign basis of its own authority. Given Claremont’s belief, inherited from Jaffa, in the priority of the Declaration over the administrative Constitution’s secondary status as mere implement, it neither defines nor constrains whatever violence “we, the citizens” conduct or institutionalize as administrative potential in redeeming the Declaration from carnage. In other words, the 2017 inaugural means the executive, speaking to define “we the citizens” as its authority and creation, as the executive’s declared sovereign will deploy violence as needed to create a new carnage to displace the old, which by the inaugural’s logic, in its liberalism prohibited the redemptive executive from acquiring salutary power.

Of the customs, laws and institutions historical subjects built, Claremont’s fantasy of natural salvation demands negation, erasure, and lingering violent destruction. To achieve the mythological sovereign power capable of all this, negation cannot stop at laws, customs, and institutions—certainly not in recognition of an opposition’s legitimate interests. It must endlessly constrain the extent of “citizenship,” the concept which empowers the agency of belonging, meriting, benefiting. As such, for the content of this sign, “the citizen,” to keep its value, the Caesar must curate its content with the agreement of those already included in the inaugural we. Take this as an instance of this ambition: since 2024 the executive’s commitment to deport non-citizens (“illegal immigrants”) and to contest the 14th Amendment’s clear statement that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state where they reside.”

Along with the 13th and 15th amendments, the 14th remade the US Constitution by assigning citizenship to all former slaves and by overturning the heinous three-fifth compromise in the original 1787 implementation of a crippled version of the Declaration’s universalist principles. Notoriously, the three-fifths compromise agreed to win slave states’ commitments to the constitutional arrangements and mechanically counted three of five enslaved persons when calculating a state’s proportional representation in the House of Representatives. The three-fifths compromise settled the slave power in control of Congress until 1865.

The anthropology of the compromise is notorious and obvious in its dismemberment of enslaved persons and homicidal in its negation of enslaved people’s humanity, their degradation into less than integral units, bodily fragments without unity. The compromise gave power to a slave logic that could extrapolate its dehumanizing rule into the basis of an unreformable state system. The slave power had become the constitutional Caesar.

Caesarism’s historical form gives plenary power to the executive and absolute impunity against all human and material laws. In the oddities of US history—and here I rely on the eyewitness expert testimony of Henry Adams—the slave power was Caesarist in its control of state power, most often by command of the government based on control of the Congress. Beginning with Andrew Jackson, slave power presidents, until Lincoln, gave the US over to a tyrannical executive Caesarism.

The Claremont Institute aspires to create a new Caesar for the US and knows that to do so it must, as a counter-revolutionary measure, overthrow the 14th Amendment particularly to reverse again, in effect, the abolition of the three-fifths compromise. If that compromise set up power by controlling votes and consolidating partisan control to delimit state decisions, then its establishment need not take the same racist form of African slavery as had occurred in 1787. What mattered was what that original compromise implied and proved: the controlling power’s right and ability to define humanity by making citizenship an openly partisan prize, that is, making the ability to be “human” within the socius, an open question. To achieve these ends, that is, the defining control over population and humanity the Right desires in its “new form” executive Caesar—the “unitary executive”—it must win over the common sense. So, Claremont creates counter-revolutionary memes—stories, talking points, friend/enemy lines—that make what Claremont and its allies call “birthright citizenship” a controversy, an unsettled question, rather than a right proven by the 14th Amendment. On October 15, 2025, an online search of the institute’s website returns thirty-five results arguing the need to disestablish the 14th Amendment. On this question and others that the institute helps generate, Claremont, as it often does, provides the arguments that create a national need that the politics essential to the Right’s seizure of power alone might meet. For its ephebes and allies, it describes the tactics to put in play the question it creates and the maneuvers to achieve it. In this instance, as is often the case, the Institute offers grounds and procedures for bringing a case to the Supreme Court confident it will concede the Institute’s arguments against “birth right citizenship.”

Amid the Right’s militarization of society by its deporting “illegal and other aliens,” “birthright citizenship” prepares steps against the 14th Amendment’s fundamental achievement, which is a legal, liberal, and common-sense obstacle to the Right’s new Caesarist ambitions. The post-civil war amendments stand as the basis for a refounding of the Republic along the universalist lines of the Declaration. As such, it is an obstacle to and proof of Claremont’s essential storyline that the nation needs a political movement that will return the US to its origins in natural law. If you will, the Right must overcome the hegemonic idea that the Declaration extends universal human rights and that the US must prove and defend them. Such a liberal notion is anathema to propagandists of natural law politics in which plenary power embodies and defends the priority of natural law against all encroachments by rights-based practice and discourse. Claremont’s second refounding, to return to natural law origins, requires sweeping away from power and politics the value, meaning, and effect of the post-Civil War amendments. Claremont takes aim through the birther movement at the 14th, so Caesarist power is unencumbered by limits on its basic power to control life and its humanity.

Caesarism extends the neo-liberal state’s power over the population in absolute ways. Deportation purges the population, settles fear as the mode of governance, and places militarized force everywhere among the people, often pre-empting the police power and the independence of states’ rights. (That shibboleth, a long enduring phrase of the conservative right, having advanced a politics tinged with the old slave power Caesarism, has disappeared from the Right’s rhetoric and irony has no power make it a roadblock to the new Caesar’s absolutely empowered national government.) Conservatives’ appeal to “states’ rights,” a residue of Jeffersonian and Virginian theories of the original founding was only an aggressive defense against the democratic republic’s assertions of federal power over states’ “peculiar institutions.” Under a Caesarist Right, those institutions more likely extend those “peculiarities” than threaten them.

Claremont prepares for SCOTUS, the Supreme Court of the United States to limit the 14th Amendment’s plain language. The tactics are clear enough. In early days of a renewed Caesarism’s control of government and given the Right’s naturalist and nationalist narrative, given its increasing control of information production and distribution as well, “birthright citizenship” rises up the chain of media importance and “culture wars” prominence. Caesarism, following Schmitt on the partisan, then uses this importance not primarily to prevent what the right vulgarly calls by the pejorative phrase, “anchor babies.”[11] That grotesque meme solidifies group identity and develops the leader / follower structure while giving popular form to the Right’s worst ambition, the nakedness of dehumanization, so clear to Plato as long ago as in the Protagoras.

The 13th Amendment ended the worst peculiar institution and with the 14th and 15th amendments enabled Congress to institutionalize the legal force enabling the national government to supersede the states’ power to define humanity along racial and sexual lines citizenship within their territories and on occasion beyond. “States’ rights” meant, after all, rights that were the states to entitle or not. Claremont and its allies ask the Supreme Court to deny the constitutionality of Congressional capacities to limit the dehumanizing power of politicized identity and, in so doing, assure the recognition of all persons’ humanity manifest in their citizenship in the nation state.

The Supreme Court’s willingness to engage Claremont’s problematic claim, that the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof,” is not transparent, suggests legal arguments that the 14th and 15th Amendments that protected free slaves and later minorities discriminated against by political power should be inverted. The Rights’ refounding must overthrow the post-Civil War’s refounding to conclude Congress does not have the power to correct discrimination against minorities, since the claim contends such action discriminates against a majority that suffers from such racially intended revision. In effect, the Right, by law, would make the first refounding part of its own carnage that turns instruments of reform that would fully humanize all persons in the nation into instruments that expose minorities to the desire of groups with definitive impunity, the holding of power that gerrymanders its own perpetuity. The new Caesarism echoes the slave power’s first grasp on power.

The Caesarist Right’s refounding renders unto Caesar alone the authority to decide who is and who is not human. Within the new arrangements, as Hortense Spillers declares, only one man is free.

Claremont has formulated maximalist tactics within the current shell of US electoral politics. Claremont’s commitment to litigation, often guided by John Eastman, a disbarred attorney who theorized the means to overturn the certified results of the 2020 presidential elections. California’s bar and courts took away Eastman’s license to practice law for practicing outside constitutional limits. Eastman might pursue his reinstatement in what he imagines will be friendlier federal courts. If he succeeds along these lines, the right will also succeed in normalizing extra-constitutional law practiced on the basis purely of power, seized and held with impunity.

Revolution against the administrative state masks a final seizure. Claremont’s role in this is large, even if not as at once pragmatic as, for example, that of the Heritage Foundation. Claremont envisions both means to and the achieved enduring Caesarism of an anti-democratic tyranny. Its refounding refers not back to the Jeffersonian Declaration or Madisonian constitution, but to pre-revolutionary forms of centralized single-person rule that often appeared after 1787 and 1789 in figures such as Bonaparte, Stalin, and Mussolini. Given the Caesarist success in creating its own paramilitary while purging the professional military of potentially unreliable leaders who famously swear loyalty not to Caesar, but rather to the Constitution, this then further parallels even the Caesarism of German National Socialism.

Although Claremont publicly associates itself with Leo Strauss and his student Harry Jaffa, in its practical activities as mythmaker, as the acid-bath of legitimacy, and as a proponent of autocracy, it belongs to a cluster of extremist political organizations of a kind once bemoaned by President Reagan’s Ambassador to the United Nations. In a famous article distinguishing among political forms of oppression and justifying American support for anti-Soviet authoritarians, Jean Kirkpatrick described an evil political form of government antagonistic to American interests and ideals. She described these enemies of America in precise terms. They were autocratic, anti-democratic, Caesarist, and uniformly self-serving. The Leninist model, which Steve Bannon openly embraces as his own model for MAGA revolution, was the perfect anti-American model of government. It took freedom from Russians and others that it ruled. It made everyday life poor and riddled society with fear. It narrowed culture to the vulgar purposes of a ruling class mostly interested in its own power and wealth. Like Bannon, Claremont and its associates took Kirkpatrick’s account of a collapsing state form that once was America’s main enemy as a blueprint for its own revolutionary action. Kirkpatrick sees that other authoritarian Caesarist regimes had the same characteristics as the Soviets. She points to the revolutionary national religious government of Iran under the control of ayatollahs, who, “display an intolerance and arrogance that do not bode well for the peaceful sharing of power or the establishment of constitutional governments, especially since those leaders have made clear that they have no intention of seeking either.”[12] Claremont is quite willing to turn the US into a regime type that America identified as repulsive and threatening in a report by the extremely conservative figure of the New Right, itself. Where once the competition between the US and Iran presented itself as a conflict of ideas and values, now, competition between a Caesarist US and a Caesarist Iran exists only as a struggle for power in which the greater power abandons its values to adopt the virtues of its lesser enemies.

We are in an American moment in which propaganda has done enough to make an extreme conservative like Kirkpatrick an implicit enemy of Claremont and the Right. In part, this is because Claremont and other Rightist thought leaders have studied Gramsci to understand the theory and practice of achieving cultural hegemony, to create a common sense in which such a moment as Kirkpatrick’s is forgotten and abandoned.[13] Current Leninist quick strike politics comes from the Right’s studying revolutionary texts, no doubt in the very universities they persistently undermine for bias. Certainly, Claremont has read and learned from both analysts of Caesarist regimes, such as Kirkpatrick, but also from Strauss’ most prominent student, Carl Schmitt. (Serious readers of early Schmitt remember that Strauss corrected his unreformed liberalism.)

If the likes of Kirkpatrick, Lenin, and various extremists lay out the mechanisms of tyranny, then Schmitt’s catastrophic study of the partisan explains the value, the effectiveness of politics made into relentless partisan warfare, but also how to achieve permanent war. The technology that in Schmitt’s analysis shows the partisan is a congruous permanent irregularity. The partisan does not fight within the regular order, hence the need to replace leaders loyal to that order with irregular political cadres. The partisan is not an extension of official power during a state of exception. Importantly, the partisan and guerrilla are not the same, for the latter does not work in the open, as a public figure, immune and empowered. The guerrilla works in the spaces opened by war, struggling against an enemy as, for example, the French Resistance filled with maquis, rural unprofessional fighters who relied on their local knowledge of terrain, fought against the Nazis. At first, the Right imitates the form of the guerrilla to place partisans everywhere in the political world of decisions and actions. Just as the guerrilla is a temporary form in a targeted struggle so the guerrilla form of carefully placed partisans in the machinery of institutions passes quickly into the partisan who knows a line, holds to it, enrages opposition, and creates a purely partisan oppositional relation in what had been republican politics.

The partisan is not only public, but professional despite being outside regular order, where partisans, having seized power, pose themselves forever. Schmitt’s partisan’s technological advantage, then, is not secrecy, local knowledge, or victory over an enemy. Rather, and Jacques Derrida noticed this decades ago, the partisan’s advantage within Caesarist politics is a permanent state of enmity: not merely an enemy it first defeats and displaces, but enmity for all that is not itself, forever. Claremont works for this final form that organizes state and techno power over and against all else, call it society, nature, culture, or questioners. While the “Left” concerned itself, as I suggest above, with the problem of the state of exception and its hypocrisies within liberal regimes, it failed to politicize an opposition to the Schmittian tactics, theory, and goal of partisan counter-revolution.[14] Often unrecognized, as part of the continuing revolution, the partisan brings war and violence everywhere. Given the Schmittian positions against the liberal state in all its post-17th century forms, one line of thought lies at the center of his condemnations and those of his followers at Claremont and in the US Right’s ambitions. Put very simply, for Schmitt, the liberal democratic republic always pretended to remove violence from politics and when secure look to suspend politics within and from the order of its own imperium. (Left critics of liberalism found Schmitt’s program useful here.) Hence, if you will, his theorizing the state of exception. According to Schmitt, to overthrow a liberal republic, however, requires partisans to bring political violence everywhere as essential element of Caesarist politics.

At this point, to hurry to an end, review Michael Anton’s video defense of Caesarism as regrettable necessity after the carnage of the liberal state.[15] The Schmittian paradigm is clear. The tactics stand out: weaken the Republic with actions and stories that calmly announce civilizational failure, a process easier than imagined when the republic has no eloquent or organized defenders. In Anton’s performance, we see the Claremont playbook: regret that a Caesar is necessary but understand that it naturally emerges from the garbage heap of democracy’s decay. Caesar appears to reground civilization threatened with anarchy. Something about the executive’s politics appears historically necessary. But to what end? Who benefits? Those who have authority, control wealth with its power, and define people as inhuman and so as waste. Partisan politics is everywhere. To create fear, a new carnage. That leaves all final authority in Caesar’s hands.

Intellectuals could devote themselves to endless discussion of the sources, qualities, and aims of this Rightist movement, accounting for the conditions of its success, the chances to displace it, and worries about its permanence. As valuable as those works will be and as happy I will be to continue to read them as they appear, for the moment it seemed best to peel back some of the cover from an important locale of the Right’s preparatory and persistent work: In the present moment, the idea that worse might come as intellectuals organic to the counter-revolution work out its end-goals and the means to sustain its winnings.

Paul A. Bové is the author of Love’s Shadow (Harvard UP), Intellectuals in Power (Columbia UP), and several other books on criticism and theory. He has also written a book on torture (HKUP). For thirty-five years, he edited boundary 2, an international journal of literature and culture for Duke UP. He retired and lives on the ridges of Southwestern Pennsylvania.

[1] James Hankins, “Hyperpartisanship,: A Barbarous Term for a Barbarous Age, Claremont Review of Books Vol. XX, no. 1 (Winter 2020): Hyperpartisanship – Claremont Review of Books. “As it happens, the most sophisticated theoretical languages for discussing issues of cultural dominance were created by Marxists during the 1930s: by Antonio Gramsci, a founder of the Italian Communist Party; by the Frankfurt School with its Critical Theory; and by Mao Zedong, who put his theories into action in the 1960s during the Cultural Revolution.”

[2] Stephen Miller, Deputy Chief of Staff to the executive and recognized planner of deportations in the second Trump administration, said on CNN that the president has “plenary authority.” (October 8th, 2025)

[3] I add this phrase to oppose (throw light on?) the clerk, Patrick Daneen of Notre Dame who strongly objects to the judgmental nature of leftist cultural politics. He makes this point at length and to great applause in Why Liberalism Failed and Regime Change: Toward a Postliberal Future. Daneen mistakes judgment for opinion when he objects to social protest and profit-motivated market formation as judgment but his own opinions on these and other matters as statements of truth. The Right’s intellectuals and petty political actors share the sophistry perfected by Claremont and its ephebes. Daneen’s defense of traditional culture comes from the pinnacle of elite academic formation and employment security. Contrast Daneen with Paul Kingsnorth to see how the rhetoric of traditional culture, profitable always on the Right, implicitly disdains a working eco-traditionalist.

[4] I do not present myself as deaf to this seduction. I began to study and write about Claremont in 2024, and I presented papers on Claremont late in the year. I have posted the talk paper I presented in late 2024 on my blog. See PAB, “The Claremont Institute: Sophistry and the Power Grab,” Critical Reflections. Inside that post is an entry to a rump essay on the machinery of Claremont. The direct link to my rump paper that does some of the work I no longer want to do here is @ https://paulbove.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/talk-paper-for-hopkins.pdf last accessed October 31, 2025.

[5] “Vice President JD Vance Honored with Claremont’s Statesmanship Award,” July 8, 2025 @ Vice President JD Vance Honored with Claremont’s Statesmanship Award – The Claremont Institute. Politico reports that “Vance is closely tied to Claremont circles, frequently speaking at their events and appearing alongside their scholars. In a statement to the American Conservative on Monday, Claremont President Ryan Williams called Vance “the ideal pick for Trump’s Vice President,” adding: “It’s hard to find a more articulate and passionate advocate for the politics and policies that will save American democracy from the forces of progressive oligarchy and despotism.” @ The Seven Intellectual Forces Behind JD Vance’s Worldview – POLITICO. last visited on 10/22/25.

[6] John C. Eastman, Senior Fellow, Founding Director of the Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence @ John C. Eastman – The Claremont Institute. Eastman earned his J. D. from the University of Chicago, clerked for Mr. Justice Thomas (1996 – 97) and served in a senior position in the Federalist Society. “In January 2023, OCTC filed 11 disciplinary charges against Eastman, alleging that he engaged in misconduct to plan, promote, and assist then-President Trump in executing a strategy, unsupported by facts or law, to overturn the legitimate results of the 2020 presidential election.” @ State Bar Court Hearing Judge Recommends John Eastman’s Disbarment – The State Bar of California – News, last accessed 10/2225.

[7] Michael Anton was Deputy Assistant to the President for Strategic Communications on he National Security Council after 2017 @ Trump’s national security spokesman Michael Anton is resigning, last visited on October 22, 2025.

[8] Mary Beth McConahey, “Publius Fellow,” Claremont Institute, answering the following question: “What’s your fondest memory of the Claremont Institute”: “I have so many memories and they’re all happy! I’m very nostalgic about my time as an intern—those halcyon days! Working down the hall from Professor Jaffa seemed the realization of an impossible dream. He was always teaching and, as interns, we couldn’t even use the microwave without getting a pretty extensive lecture on Lincoln or Shakespeare or Aristotle or Aquinas or Churchill or all of them combined. It was awesome.” @ Mary Beth McConahey – The Claremont Institute, last visited October 22, 2025.

[9] Reread Wallace Stevens, “The Man on the Dump,” which includes the line, “One rejects / The trash.” Claremont, we can say, fears this possibility of rejecting its own ruination because as Stevens says, “and the moon comes up as the moon / (All its imagines are in the dump) and you see / As a man (not like an imagine of a man).”

[10] The New York Times January 18th, 2025, reported that “The incoming State Department official Michael Anton has spoken with [Curtis Yarvin] about how an American Caesar might be installed into power.” Yarvin is best known as an advocate for monarchy, kingship, as the best, proper, and necessary form of sovereign executive for the post-constitutional United States. In The Claremont Review, Yarvin’s name appears only once. during a word search of the magazine, and this in an article by Michael Anton, “Are the kids Al(T) Right?” who refers to Yarvin as “the well-known anti-democracy blogger” (Summer 2019).

[11] On CNN’s New Day, August 19. 25. Cf. CNN Transcript, CNN.com – Transcripts and per Politifact, on August 19, 2015 in New Hampshire, then candidate Donald Trump said “his plan to roll back birthright citizenship for children of illegal immigrants will pass constitutional muster because ‘many of the great scholars say that anchor babies are not covered.’” PolitiFact | Trump: ‘Many’ scholars say ‘anchor babies’ aren’t covered by Constitution. All last accessed November 10, 2025.

[12] “Dictatorships and Double Standards,” Commentary (November 1979), reprinted by America Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1979, p. 34. Ambassador Kirkpatrick was then a fellow of his Institute.

[13] For a belated and seemingly surprised recognition of the Right’s sophisticated Leftist grasp of liberal politics’ weaknesses, see the civilized conservative, David Brooks, “Hey, Lefties! Trump Has Stolen Your Game,” The New York Times, October 30, 2025, @ Opinion | Hey, Lefties! Trump Has Stolen Your Game. – The New York Times, last accessed October 31, 2025.

[14] Cf. Edward Luce, “Democrats are locked on campus: In politics you are what you talk about,” The Financial Times October 31, 2025, @ Democrats are locked on campus, last accessed on October 31, 2025.

[15] It would help to understand Claremont’s aims, the effectiveness of its training, and the sufficiency of its tools to look through Anton’s book, The Stakes: America at the Point of No Return (Regnery, 2020). The book is fine and revealing propaganda, spreading fear, stoking nostalgia for a lost “origin” (California before immigration). Most important is its style, marked by the declarative sentence, easy accessibility, and the partisan’s battle against qualifications, evidence, and alternatives. Linearity to produce false memories to create nostalgia stoking resentment, and willing to adopt partisan stories as its own.