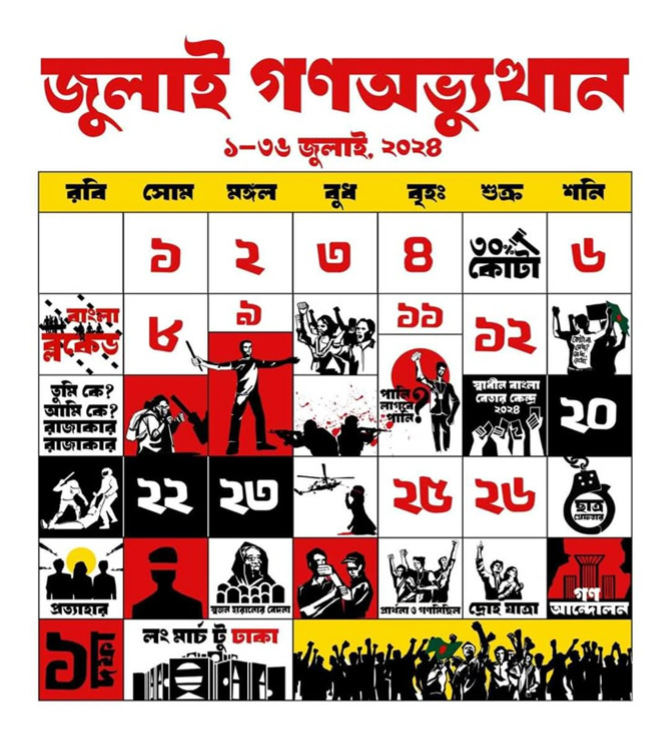

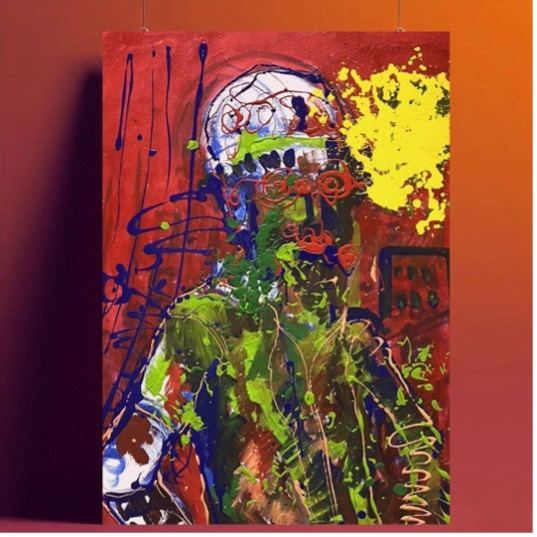

Figure 1, © Reesham Shahab Tirtho, Calendric Rendition of the Events of July 2024

This post is Part Four of “The Bangladesh Chapter” of the b2o review’s “The University in Turmoil: Global Perspectives” dossier.

How to Reclaim a University: Further Lessons from Dhaka

Bareesh Hasan Chowdhury, Shrobona Shafique Dipti and Naveeda Khan

Introduction

On 5 August 2024, the student-led Anti-Quota Movement that lasted the “36 days” of July culminated in a large gathering of people in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh.[1] The Long March to Dhaka (as it was called) indicated the tremendous support that the students had from ordinary Bangladeshis. It effectively brought about the fall of the Awami League-led government that had ruled Bangladesh with an iron fist since 2009. Sheikh Hasina, the then Prime Minister, was compelled by the military to flee the country, fearing the force of popular anger against her. The July Uprising has since gone down in Bangladesh’s short history as one of the most important student-led movements. Whether it has changed or will change the course of the nation’s history is still being deliberated.

Several points are important to underline with respect to this movement. The movement took shape and built momentum within Dhaka University, the premier public university of Bangladesh, which (as we showed in our earlier installment) was thoroughly captured by the student wing of the ruling party, the Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL). The university-based origin of the movement might surprise us given the extent to which party hacks and thugs were entrenched within the university administration and the student body. However, it ought not to be surprising given the long history of general student dissatisfaction with the intrusion of national politics into the university. Furthermore, student commitment to collective action had been repeatedly demonstrated from the 1990s onwards. The real surprise, rather, lay in the movement’s successful toppling of a political regime, an outcome which went well beyond the movement’s seemingly modest intent of reforming the quota system for government jobs.[2]

In this fourth installment of the “Bangladesh Chapter” of the b2o review’s “University in Turmoil” dossier, we provide a careful plotting of the events marking the month of July leading to the August 5 denouement to track how the movement built momentum, how it spread to other educational institutions, and how Dhaka University was ultimately reclaimed. As we will show, attention to the micropolitics of organizing, including the mobilization of symbols and symbolic behavior, can shed light on the success of this movement, while nevertheless retaining the perspective that the movement’s ultimate success was a surprise to all. We want to emphasize how different sections of the population came to exert ownership over the movement even if the issue which launched it was not theirs. After all, the issue of getting government jobs was surely of remote interest to the young secondary school children or working-class people who came to be involved in the protests. The enthusiastic participation of female university students in the Anti-Quota Movement was even more paradoxical, as they were effectively asking for the removal of gender-based quotas, a mode of affirmative action long vaunted for ensuring women’s participation in the workforce; their removal could only harm those women students. While we have written about these women’s understanding of their participation earlier and will dive deeper into it in a future installment, in this submission we focus on certain events and deaths during the movement that produced pathos and an inadvertent alignment of sympathies across different constituencies of Bangladeshi society, leading to broad based support for an initially more limited movement.

Figure 2, Downloaded from Facebook “Medha Chottor,” Quota Movement 2013

Figure 3, ©Rahat Chowdhury, Quota Movement 2018

Figure 4, ©Palash Khan, Quota Movement 2024

Grounds of Protest

The 2024 Anti-Quota Movement was the third of its kind. The first in 2013 was entirely scuttled by government forces. The second in 2018 also encountered state violence but eked out a concession from the government to scale back quotas from 56% to 35% and to scrap the quota for freedom fighters, a decision that was announced through a governmental circular. However, following the High Court of Bangladesh’s 2024 decision to “revert” the government circular and reinstate quotas on government jobs, including the controversial 30% quota for freedom fighters and their children and grandchildren, the students again took to the streets.

An entrenched quota system deprived youth in the general population of access to desired governmental jobs. A quarter of Bangladesh’s population of 171.5 million people are youth, that is, 45.9 million people are between the ages of 15 and 29. The Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics’ 2023 Labor Force Survey estimates that there were almost 2 million unemployed youth in the country. As not all youth sought employment in the formal sector, with many in agriculture and the informal economy, this number of unemployed youths was considered very high. Of this number, 31.5% had completed higher education beyond the secondary level. The percentage of those with higher education indexed aspiration to employment either in government or the private sector, with a preference for governmental jobs, as these have typically provided job security and benefits.[3]

Governmental jobs were also desirable for being endowed with a high status that derived from the Bangladesh Civil Service (BCS) originating in the Imperial Civil Service in colonial India. The British put into effect an elaborate structure by which to bring Indians into government, investing the bureaucracy and its competitive entrance exam with considerable exclusivity and entitlement. It effectively produced a new class of Muslims within Indian society deemed the salariat, a class whose aura surrounds government employees even today. Consequently, the exam for entry into BCS exerted tremendous attraction and pressure on the youth population as a means of upward mobility, with many taking years out of their lives to prepare for the test, taking the exam repeatedly, if necessary, in order to keep alive the opportunity of entering government service.[4]

To compound youth unemployment rates at this moment, there were several worrying trends that undermined the ruling party’s long-standing narrative of development, growth and prosperity, suggesting, indeed, that the Awami League’s much vaunted economic development was illusory. Until this point, the AL government had extolled 6% annual growth, positioning itself as the party of development, with its development agenda heavy in infrastructural works, specifically bridges and tunnels, to improve the interconnectivity of the country. However, inequality had risen over the past few decades, followed by a cost-of-living crisis since 2022, itself intensified by rising food and energy prices, all of which the government had failed to so much as acknowledge. And Bangladesh was not immune from the global economic slowdown in the aftermath of the Covid 19 pandemic. Those in the middle class who had experienced prosperity and higher standards of living suddenly felt themselves banging against a hard ceiling. Those who had come out of poverty fell back into it. Beggars whose presence on the streets of Dhaka had waned once again grew in numbers. It appeared that the AL’s economic miracle was on shaky ground.

In the University and Outwards: The Events of 2024

The students who led the 2024 Anti-Quota Movement began as a group calling themselves the Students Against Discrimination (SAD). While the leadership of the prior 2018 Anti-Quota movement had moved on to national politics, the young who had participated in that earlier movement now provided the leadership of SAD. SAD came to be reinforced by more youth who had been exposed to other social movements throughout their young lives, often against the inadequacies and injustices of the authoritarian state. Notable among these was the Road Safety Movement of 2018. SAD operated with a new understanding of organization, that there would be no centralized structure or leadership hierarchy within the movement. These reforms came out of the movement prior experience of state violence. As we have explored in an earlier installment, this decentralization may have been the key to sustaining the movement in the face of heavy repression. In the rest of this section, we explore, by recounting the events of the summer of 2024, the other elements that also came into play when scaling up the movement into a mass protest.[5]

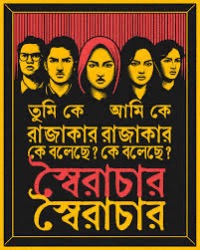

Figure 5, ©Debashish Chakrabarty, Poster used by Protestors, “Who am I Who are you Razakar, Razakar Who Said This? Who Said This? The Dictator, The Dictator”

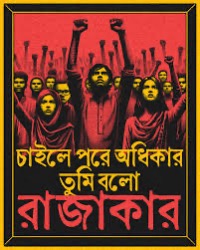

Figure 6, ©Debashish Chakrabarty, Poster used by Protestors, “Upon Asking [You] for Rights, You Say, Razakar”

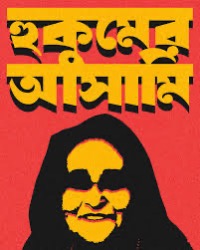

Figure 7, ©Debashish Chakrabarty, Poster used by Protestors, “Accused by Command”

Following the High Court’s decision in early June, university students across the country took part in peaceful protests, with Dhaka University serving as the center of dissent. Female students at Dhaka University took the lead here. The protests gradually escalated over the course of the month until in early July, SAD called for the “Bangla Blockade,” the name given to the street sit-ins that blocked roads. Among other sites, this blockage took place on the Shahbagh intersection adjacent to the university campus. On 14 July, at a press conference held to mark her return from a state visit to China, which had ended none too well, with the prime minister returning early on the pretext that her adult daughter was sick at home, Sheikh Hasina was asked her opinion about the student unrest, specifically about the fact that the students were seeking to scrap the quota for freedom fighters. Hasina exasperatedly said “Why do they have so much resentment towards freedom fighters? If the grandchildren of the freedom fighters don’t get quota benefits, should the grandchildren of Razakars get the benefit?” In Bangladesh, the term “razakar” (literally collaborator) is used as a pejorative term to mean “traitor” in order to refer to those who collaborated with the Pakistan Army during the 1971 War of Liberation. Hasina’s trivializing of the protests enraged the students, and in a remarkable reversal of the usual repulsion felt towards the category of the “razakar,” they decided to embrace it. They demonstrated with the slogan “Tumi ke, Ami ke, Rajakar, Rajakar,” (Who are you, Who am I, Razakar, Razakar), followed by the slogan “Key Bolechey, Key Bolechey, Shoyirachar, Shoyirachar” (Who said this, Who said this, The Dictator, the Dictator). In taking on the label of razakar, in defiance of its bad associations, they marked Sheikh Hasina as a capricious authoritarian figure who delegitimized her opponents and dissidents by calling them razakars. Their words also questioned the right of the Awami League to serve as the custodian of the Liberation War if it was going to instrumentalize the liberation struggle to stifle criticism. Hasina’s thoughtless comments recruited a new round of protestors, and soon the above slogan unfurled everywhere.

In a clear indication that the standing government conflated the party’s muscle with the nation’s police forces, the General Secretary of Awami League (Obaidul Quader) and the President of BCL (Saddam Hossain) called on Dhaka University BCL students to control the student protestors. BCL members openly declared their intent to teach a lesson to the student protestors for what they claimed was their disrespect towards Sheikh Hasina, freedom fighters and “the spirit” of the war of independence.

On 15 July, quota reform protesters gathered and set off from the Raju Memorial Sculpture near the Teachers Students Center (TSC) on campus. This memorial was erected in 1997 in memory of the 1992 student protests against the political capture of their campus. Consequently, the gathering around it at this moment was seen to reanimate the call for an education without political interference. The location and organization of the protest were redolent with choreographed symbolism.

Figure 8, Downloaded from Jamhoor, Image of BCL Violence on Women that Went Viral

The student protestors were ambushed by BCL members who carried sticks, hockey sticks, rods, GI pipes, and other weapons. At least five individuals were observed firing pistols on campus. Student protestors received beatings at various locations of the university. In flagrant disregard for university governance, beatings occurred in full view of the Vice Chancellor’s residence. BCL members even stood outside of nearby hospitals, such as the Dhaka Medical College, attacking wounded demonstrators as they were taken there for treatment, at one point even entering the emergency department to attack protesters and eject them from the premises. Although both men and women protestors were hurt, the images of women being attacked were most shocking for onlookers. An image went viral showing a young woman wincing, her face covered in blood, while a BCL member raised a stick to beat her. This incident, along with others at which mostly women were beaten by the BCL, sparked public outrage and incited strong sentiment against the group.

On 16 July, the protesters came prepared to fight back, gathering at the Shahid Minar, the memorial to the martyred student activists of the 1952 language movement, also on the Dhaka University campus. This choice of memorial may be seen as communicating a symbolism different from the Raju Memorial’s, as it expressed resistance to foreign occupation, indicating a growing sense of the Awami League government as an occupying force. The police, who had finally joined the fray, stood between the students gathered at the Shahid Minar and the BCL members who held the area around the Raju Memorial, having seized it from the student protestors the day before. They were gathered to stop the students from marching on the Raju Memorial and to prevent further bloodshed, since the protesting students were by now resolved to return the beating that they had been getting. However, the police were soon causing the very bloodshed they had been deployed to prevent.

Figure 9, ©Zabed Hasnain Chowdhury, Women of Ruqayyah Hall, Dhaka University

Figure 10, ©Zabed Hasnain Chowdhury, Women of Ruqayyah Hall, Dhaka University

On the night of 16 July, the women students took the lead in the pushback against BCL. In one instance, the women residents of Dhaka University’s Ruqayyah Hall chased BCL leaders out of their “halls,” as their dormitories on campus were called. Once vacated, the rooms occupied by BCL student leaders showed the luxury in which they had been living while subjecting their fellow students to deprivation and intimidation. Students enraged by this sight destroyed the rooms. Whereas they had up until this point engaged historic sites and symbols (razakar, Raju Memorial, Shahid Minar) to place their movement on a continuum with known history, their mode of protest now shifted into an iconoclastic mode—instead of mobilizing symbols and images, the protestors began destroying symbols of power and desecrating images.

Typically, such women’s halls maintained strict curfews, with the gates to their halls locked by a certain time at night. On that night, the residents of Ruqayyah Hall also broke the locks to pour out into the streets to protest. Other halls soon followed in chasing out BCL leaders and taking their protests to the streets, joined by their male counterparts.

Student protests spread and intensified across the country. Jahangirnagar University, the University of Rajshahi, Begum Rokeya University in Rangpur, and many other universities joined. And reports of fatalities began to surface of students either killed at the hands of the BCL or the police.[6] In the city of Rangpur, Abu Sayeed, a student of English at Begum Rokeya University, was shot dead while he stood with his arms spread, clearly unarmed, as if daring the police to shoot. He was killed by rubber bullets shot at close range. He was the first to be martyred in the Anti-Quota Movement, which was quickly earning the moniker of the July Uprising or Bloody July. A total of six people across the country were killed that day.

Figure 11, ©Faysal Zaman, Gayebana Janaza

On 17 July, in keeping with the use of symbolism to affect a politics of protest, the Anti-Quota Movement organized a gayebi janaza, an absentee funeral for those who had disappeared or were killed to draw attention to the deaths of protestors. In Dhaka University, it was performed in front of the Vice Chancellor’s residence to shame the university administration for its failure to protect its wards. In many places the police prevented this service from being performed, which was taken to be a stark act of erasure. And in a show of yet more shameful dereliction of its duties towards its students, the university administration announced the shutdown of Dhaka University, ordering students to vacate their residential halls. The students tried to resist by barricading the gates to the dormitories. In a now familiar modality of mocking through mimicking, they sent a counter-notice to all university administrators requesting them to vacate their official housing on the grounds of failing to uphold their duty as guardian. Ultimately, sound grenades and tear gas were mobilized to force students to vacate, with many seen leaving in a hurry with their bags and baggage. If previously the government had merely attempted to swat away the movement using their student forces, now their efforts to dismantle the Anti-Quota Movement were in full swing, with the police, the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB, an elite paramilitary force), and the Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB) stationed in major cities around the country. The army was not brought in until later.

From 18 July onwards, the scene of action shifted from Dhaka University, vacated of students, to other sites of confrontation. For instance, we have already seen how students in major cities such as Chittagong and Rajshahi were involved. They were now joined by students in tertiary cities such as Rangpur, Khulna, Comilla, and Sylhet. It is notable that the universities initially central to the movement in Dhaka, Chittagong and Rajshahi were public institutions. But now students from smaller, private universities joined the protest wave.

On 18 July, the big private universities in the Rampura-Badda area of Dhaka brought out large solidarity protests, congregating in front of BRAC University. Universities serving the children of the country’s elite came out in solidarity with public university students. The private universities, having outlawed political parties from their premises, were historically known for their apolitical nature. And the students themselves were seen as largely apolitical, more oriented towards starting international careers than the less privileged students, who were both more committed and more entrenched within the Bangladeshi context. This congregation of private university students was met with police violence and threats of open fire – an unprecedented attack on the children of wealth, who had previously been exempt from this type of state brutality. While other private schools in the area kept their gates closed to student protestors, BRAC University opened its gates to them and converted their space into a makeshift medical bay. One protester from the nearby Imperial College died on the BRAC University campus, one of at least 30 who were reported dead on that day from across the country.

How do we understand the spread of the movement from DU to other institutions and across the country? As we have pointed out earlier, one reason the was able to fan out when faced with blockages from the state was its decentralized organization, with multiple coordinators stationed autonomously across the country. However, this cannot be the full story. For how are we to understand the coming on board of the students of private, elite institutions, who were not part of the initial planning of the movement? How, too, can we explain the participation of children from secondary schools? It was in all likelihood the graphic death and martyrdom of Abu Sayeed and the others who soon followed him that fueled the expansion of the movement to include many more students and ultimately ordinary working people.

Figure 12, Downloaded from Wikipedia “Abu Sayeed”, Artistic Rendition of Abu Sayeed, one of 100s

Figure 13, Downloaded from Mahadi Mishu Instagram, Artistic Rendition of Mir Mughdo, one of scores

Figure 14, Downloaded from Reform Bangla, Artistic Rendition of Shaykh Ashabul Yamin

Figure 15, ©Hrifat Mollik, Artistic Rendition of a Member of the Security Force, Whose Green Blood Shows Him to be an Alien

Abu Sayeed was killed in Rangpur on 16 July. The video of his murder went viral in no time: it showed him being shot repeatedly by police in riot gear, with him flinching, yet stretching out his arms several times, falling into a crouch on the ground, and finally having his prone, presumably dead body hauled off by a group of young men. This video had a profound impact on the minds of people, including the young. Almost immediately the students at secondary schools, such as the Residential Model College in Mohammadpur in Dhaka, came out in protest. And the shock and pathos of Abu Sayeed’s unprovoked death was amplified by the death of one of these young students, Farhan Faiyaz, on 18 July. Farhan Faiyaz’s death was followed by the death of a university student activist Mir Mugdho, a student at the Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP), who was killed in the act of handing out water to protestors in Dhaka. Dhaka’s Military Institute of Science and Technology student, Shaykh Ashabul Yamin’s death in several parts is probably seared in people’s minds as the most terrifying display of state violence in recent memory. In videos and photographs we see how he was thrown from the top of an armored personnel carrier. He fell on the road with his arms outstretched, and his legs folded behind him, still visibly alive. The police then dragged him across the road and hurled him across the divider onto the service lane at which point he likely died. As mentioned above, this was the most brutal day of the movement thus far, with thirty dead the country over.

Figure 16, ©Doha Chowdhury, The Daily Star. Students Renaming the Gate Rudro Arcade

These deaths galvanized the country into reacting with tremendous grief and anger openly voiced. Of course, Bangladeshi society was no stranger to the deaths of its citizens in the hands of state forces. To understand why these deaths would produce such outpourings it may be necessary to investigate the antipathy that had built against Sheikh Hasina’s repressive and violent regime but most immediately it would appear to be the senselessness of the deaths. Student protesters immediately started to give gates and streets the names of those killed, as if to restore meaning to these deaths. On 17 July, right after Abu Sayeed’s death, students demanded that Rangpur Park be renamed Abu Sayeed Chottor (Square). At Shahjalal University of Science and Technology (SUST), a gate was renamed Rudro Toron (Arcade) for Rudra Sen, killed on 18 July, while Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP) renamed a floating bridge Shaheed (Martyr) Mir Mughdo Bridge. These were not just tributes. They were refusals to let the state dictate who was to be mourned and how. On 30 July, when Sheikh Hasina attempted to grasp the reigns of memorialization by declaring it the day of mourning or “Jatiya Shokh,” students rejected her bit outright, saying “Rokter daag ekhono shukay ni,” (the stains of blood have not yet dried) and turning all their profile pictures on various social media platforms red in protest.

By this time, it was clear that social media was by far the most important media element within the movement, getting images, videos and commentary out before news media were even alerted. On the evening of 18 July, the government imposed a shutdown on social media and internet access, which extended to mobile and broadband internet, and platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and WhatsApp. However, through various technical workarounds and diasporic connections, videos of protests and state violence continued to be distributed abroad, although inaccessible to those within the country. At home, all one could do was watch TV and read the dailies, which reported assiduously, though given the extent of censorship in the country, official coverage was treated skeptically. Many reported feeling that the established media made them doubt the veracity of what they were themselves seeing and experiencing at the time.

The international media gave the events some sputtering attention, being more captivated by the transfer of candidacy from Biden to Harris in the United States. However, a few reporters of Bangladesh origin such as Tanvir Chowdury of Al Jazeera and Shafiqul Alam of Agence France Press (AFP) Press kept their focus on the country. Al Jazeera covered Yamin’s brutal death, for one thing. Offshore news outlets, such as Netra News, and overseas bloggers, such as David Bergman, Zulkarnaen Saer and Tasneem Khalil, kept snippets of news flowing.

Diaspora Bangladeshis, including students, came out in the hundreds to draw attention to the death-dealing activities of the AL government. There were massive protests in front of the Bangladesh consulates in New York City, London and Berlin. Some risked punishment to protest, such as a group of migrant workers in the UAE who were promptly put to jail (they were later released upon the intervention of Muhammad Yunus, the head of the interim government that came to replace the AL-led government). Migrant workers stopped sending remittances through official channels to express their anger against the government, effectively compounding the pressure on the government, making its survival even less likely.

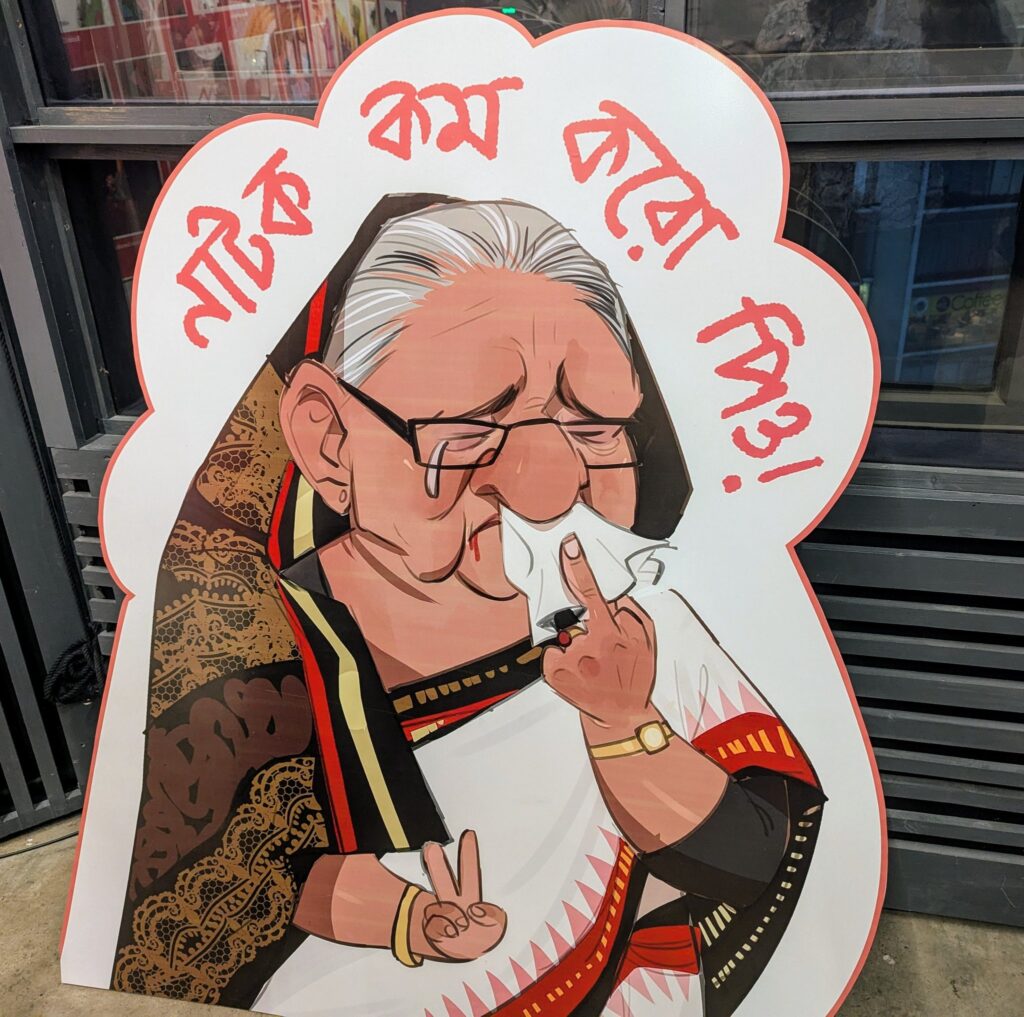

Figure 17, ©Mehedi Haque

In Bangladesh, opposition political parties, such as BNP and Jamaat-i Islami called for general protests. Civil war raged in the cities, with the burning of several official establishments. Newspapers reported Sheikh Hasina’s eyes tearing up seeing the damage done to a Dhaka Metro Station newly inaugurated by her regime. These tears prompted many rebukes and jokes about her love for property over people. The police effort to dismantle the movement now took the shape of intimidating student leaders. Nahid Islam, a student coordinator who had been particularly visible in the press, was picked up on 19 July and found unconscious with clear marks of abuse on his body on 25 July. He was again detained and kept in police custody with five others between 26 July and 2 August. The army was deployed on 19 July, but it was reported that the army would not shoot; instead, it would provide protection to the police and RAB. This effectively allowed the security forces to use lethal force without fear of being overwhelmed by the increasingly angry masses as the army stood guard over them. The police took to the skies in helicopters and snipers to the tops of skyscrapers to shoot indiscriminately upon gathered protestors, even hitting those sheltering in their homes, including young children.[7]

On 21 July, a rattled Awami League government began to seek compromise, saying that they would abide by whatever the Supreme Court decided regarding quota reforms. On 22 July, the appellate division of the Supreme Court reduced quotas from a total of 56% to 7%, with 5% reserved for freedom fighters and 2% for ethnic minorities, transgender people and those with disabilities. But by this time many more people had died.[8]

The sense of the moment was that quota reform could no longer be an adequate appeasement for the sheer numbers who had given their lives in protest. The nine-point demands that were articulated at this moment were: PM taking blame and formally apologizing for the mass killings, the resignation of various ministers who were also in the AL leadership, the firing of police officers present at the areas where students were killed, the resignation of the Vice Chancellors of Dhaka University, Jahangiranagar University and Rajshahi University, the arrest of those police and individuals who attacked or instigated attacks on students, compensation for families of those who were killed or injured, the banning of BCL, the opening of university halls, and an end to the harassment of protestors.

At the same time, SAD announced a suspension of the movement after the appellate decision on 22 July, while demanding the lifting of the ban on the internet. Between 22 and 28 July, there were no student protests. Instead, there was an efflorescence of many small protests by teachers, lawyers, artists, and other members of civil society, including actors and celebrities. Various figures called press conferences asking for student leaders to be released and student demands to be heard and constructively engaged. Between 22 and 26 July, the government declared that the student movement had been infiltrated by external forces, hinting that the USA was inciting the protests. It turned its focus on opposition parties, such as BNP, Jatiyo Party, even the small parties, such as Gono Odhikar, that had emerged from the 2018 Anti-Quota Movement. It declared a ban on the religious party Jamaat-i Islami. Everyone in the leadership of these parties was picked up and jailed through dramatic and terrifying block raids at their places of residence and neighborhoods. The government imposed a curfew from 26 July onwards, with street traffic allowed for just a few hours each day to allow people to get necessities.

From 29 July onwards the momentum of the movement, which had left Dhaka University to enter the streets, returned to the university, this time through the agency of teachers. On 29 July, teachers across campuses and political divides organized as the Teachers Platform Against Oppression to hold a rally at the foot of the Aparajeyo Bangla monument on the campus of Dhaka University. The choice of this monument commemorating the 1971 Liberation War struggle as the place of gathering and criticism of the government suggested that no one, much less the Awami League, could claim a monopoly over the Liberation War. One teacher even gave the example of a teacher, Professor Shamsuzzoha, who had died protecting his students in 1969, claiming him as their inspiration, thus putting this rally in a direct line of continuity with the struggle against Pakistan. Teacher after teacher gave moving speeches on the right of students to protest, excoriated the inordinate violence against them, and demanded the release of those detained. And, most significantly, they called on ordinary people to fight their fear and come onto the streets.

On 2 August, thousands convened in front of the National Press Club close to the university before slowly marching to the Shahid Minar as part of the Droho Jatra (literally, Rebellion/Revolt Journey). Here the variously changing demands coalesced into one calling for Sheikh Hasina’s resignation. On 3 August, the gathering at the Shahid Minar was even bigger. The student anti-quota movement originating in Dhaka University had met with state violence, been forcefully evicted from the campus, and now returned to the premises with tens of thousands from all sections of society behind the students.

Figure 18, ©Abdul Karim Khan, Gathering for the Long March

On 4 August, there was a nationwide call for a Long March to Dhaka for 6 August, later brought forward to 5 August. The Awami League government continued its violence against protestors, which now included more ordinary people than students. The BCL famously took to social media to declare it would take “7 minutes” to clear the protesters in a defiant last stand. The battle raged on the streets across Dhaka and the country. A 100 people lost their lives on 4 August, more than half of whom were BCL and AL activists and the police.

Ultimately the public turned to burning police stations to express their anger at the indiscriminate use of lethal force against those unarmed and the cruel disposal of the dead and in some cases yet living bodies. On 5 August, hundreds of thousands of people poured into the city of Dhaka despite attempts to prevent entry, an imposition of curfew and a short internet blackout in the morning. The army refrained from shooting, despite Sheikh Hasina’s pleading for it to do so. Instead, the Head of Army Staff and Hasina’s family persuaded her to get into a helicopter that flew her and her sister to India, her departure leading to the fall of the AL government.

Conclusion

Through plotting the events of July 2024, we hope to have shown how a student led movement, which started within a university thoroughly captured by the state, and with only a limited goal of winning a few compromises from the state, ended up overturning the state. At each point as the students encountered state violence where they expected state engagement, their demands ratcheted up to keep faith with those amongst them who died simply trying to get the state’s attention. The strategic arrangement of student leaders across the country ensured that the movement continued even as the most visible figures within it were taken into “safe custody” by the security forces. The pathos surrounding those killed unprovoked and senselessly brought more and more students and ultimately the general populace into the protests. And, at one point, the sacrifice in human lives became so steep as to make nonsense of the initial demand for quota reform, bringing on the demand for Sheikh Hasina’s resignation.

A further set of perspectives on the nature of Sheikh Hasina’s regime may be culled from our focus on Dhaka University as the site of capture by the ruling party’s student wing, the BCL, and the subsequent efforts to reclaim it. In some respects, by trying to establish their authority within the university and take control over its resources, the BCL was only doing what student groups associated with national level political parties had always done. Afterall, it was assumed that the ruling party, any ruling party, and their affiliates would engage in extortion as a benefit of being in power.[9] But what was different in this instance of Sheikh Hasina’s rule was her determination that AL would rule in perpetuity and that its control over all resources and opportunities would be absolute. And the BCL in Dhaka University projected this sense of permanence in its thoroughness of extortion, providing an important vantage on the thinking and workings of the government. It also made the BCL not only the object of fear and loathing but a proxy for the government. Thus, attacking the BCL was felt to be tantamount to launching an attack at the state, with the defeat of the BCL making the downfall of the state a real possibility.

The student-BCL inter-dynamics and conflicts within the university played out in miniature relations between civil society and state, going so far as to provide a template for how civil society may resist an oppressive state. As the capture of the university had taken place one site after another, one cherished student tradition after another, so was its reclamation site by site, starting with the female students throwing the BCL out of residence halls to be followed by others. Some within the BCL even flipped sides, while others who stayed loyal targeted for reprisals after 5 August. After the fall of the government, it was disclosed that several members of BCL’s leadership were students of other political groups who had infiltrated the group to undermine it from within, but that is a story for another time.

The students, first seeking to advocate for administrative reform and later to withstand the force of the state embodied by the BCL and then the police and RAB, deployed a range of well-known techniques within the activist’s toolkit. For instance, they undertook peaceful demonstrations and marches. They took advantage of the symbolic importance of monuments and other historic sites within their campus at which to express themselves, associating their struggles with prior moments and struggles. They maintained a unified voice albeit refracted through many different leaders and coordinators. And in a venerable tactic, not only did they resort to violence to defend themselves, they, along with the general populace instigated destruction, including the burning of police stations and the killing of the police, to express their anger at the violence directed at them.

They also introduced new elements into the revolutionary’s toolkit by ventriloquizing those who sought to discredit them, a risky discursive strategy in the best of times, such as when they took on the slur of razakar. They performed funeral services for those who had been disappeared, giving their movement not just the ebullience of resistance but also a funereal affect. They widely used social media not just for the purposes of reportage but for bearing witness and bringing onlookers into the tragedy of death and the proliferation of martyrs, which had the effect of drawing sympathizers into the protests.

Since 5 August 2024, Dhaka University has once again become the political center of the city. Shortly after the fall of the government, there have been many Bijoy Michil or victory marches in Shahbag. Chobir Hat, a place of gathering of progressive students, reopened after being shut for over a decade with a concert honoring those who had died. There have been enumerable academic and journalistic events hosted on campus inquiring into different dimensions of the uprising, such as enforced disappearances or the art of the uprising. There has even been a concert by the rap artist who had been persecuted by the regime because he was an early and vocal supporter of the Anti-Quota Movement. Most importantly, it has become a place where everyone returns to stage their protests directed at the current interim government. The protests are to be found at the base of the Raju Memorial.

Bareesh Hasan Chowdhury is a campaigner working for the Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association on climate, policy, renewable energy and human rights.

Shrobona Shafique Dipti, a graduate of the University of Dhaka, is an urban anthropologist and lecturer at the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh with an interest in environmental humanities and multi-species entanglements.

Naveeda Khan is professor of anthropology at Johns Hopkins University. She has worked on religious violence and everyday life in urban Pakistan. Her more recent work is on riverine lives in Bangladesh and UN-led global climate negotiations. Her field dispatches from Dhaka in the middle of the July Uprising may be found here.

[1] It was colloquially said that July did not end until the movement ended and, as such, 5 August has come to be referred to as 36 July.

[2] To remind the reader, this demand was brought on by the criticism of the large quota for the freedom fighters associated with the 1971 Liberation War of Bangladesh and their family members, one considered to be widely abused to favor Sheikh Hasina’s party members. Despite the increasing authoritarianism of the AL government, previous student movements had been able to eke out limited compromises from the government, which spurred the 2024 Anti-Quota Movement.

[3] It is noteworthy that there had been a meteoric rise of private educational institutions across the country to manage the rising numbers of people desirous of social mobility through education and employment, particularly as public education systems had either started failing due to governmental disinvestment or being structurally unable to absorb the growing numbers.

[4] Among the reforms the interim government, in place after the fall of Hasina’s government, has undertaken to the BCS exam is to raise the age cap to 32 from 30 but to restrict the number of times a candidate may take the exam to three. See: https://www.thedailystar.net/news/bangladesh/news/exams-public-jobs-govt-raise-age-limit-32-years-3735386?fbclid=IwY2xjawGG8P9leHRuA2FlbQIxMAABHe2vaTdmMKINRzH8CFYZYD5EbAMmfx6UbgzFoUMLux5sqr12-VZT_Y3zRg_aem_dl61jR5NJn2sdGRHtAn7lg

[5] There are by now several important accounts with timelines of the July Uprising. Our intention in providing yet another one is to more self-consciously center the Dhaka University in these accounts and timelines in order to ultimately show how the university was reclaimed.

[6] It is notable that several BCL activists were also killed in retaliation, which led them to be outraged at the leaders of Awami League who they felt had effectively set them up.

[7] The deaths in the July Uprising included a disproportionate number of young people, including very young children.

[8] Later speculation about the numbers killed over the course of long July would bring the number to 1000, later marked up to 1400+ by the Office of the Human Rights Commissioner and 1500+ by the Students Against Discrimination.

[9] And in keeping with that practice, no sooner did the AL led government collapse, than BNP members stepped into the extortion rackets abandoned by fleeing AL party members.