Image taken by author.

This article is part of the b2o: an online journal special issue “(Rhy)pistemologies”, edited by Erin Graff Zivin.

Rhythmic Concepts and New Knowledge

Maya Kronfeld

My collaboration with Michael J. Love (see video below) is an attempt to work against the all-too-common backgrounding of rhythmic forms and their epistemic contributions.* Rhythm in jazz and Black music more generally is often trivialized and denigrated even when it is being applauded – the proverbial “damning with faint praise.” Specifically, when the complexities of polyrhythm and swing are admired, they are increasingly treated as decontextualized, ready-made ratios to be labeled and then implemented according to some “cheat code.” Unlike melodic and harmonic virtuosity, the rhythmic language that takes decades of study to acquire, develop and master often does not even register as a zone of competence. Reducing or denying rhythmic knowledge-making and the central role it plays in the music has always formed part and parcel of the fear and control of blackness and black form, especially as jazz gains what Rey Chow calls “cultural legitimation” (Chow 2010; E. Davis 2025; Ramsey 2004; Lewis 1996).[1]

“One of the most malevolent characteristics of racist thought,” Toni Morrison writes in her foreword to the novel Paradise, is “that it never produces new knowledge… It seems able to merely reformulate and refigure itself in multiple but static assertions” (Morrison 1998: xv). In a photo from Morrison’s 1994 collaboration with Max Roach at the Festival d’Automne in Paris in 1994, one glimpses the new forms of inquiry that emerge from the interplay between verbal and rhythmic art.[2]

I elaborate the literary dimension of my argument elsewhere (Kronfeld 2025), but I include Morrison’s critical observation here to clarify what’s at stake for Love and me in our artistic and scholarly practice and help us shake off some tired old binaries about the relationship between aesthetics and politics. Jazz’s emphasis on the new emerges precisely in the context that Morrison describes: jazz and other experimental art forms are not inherently radical (a fact which is crucial to their radical potential) but rather contain the prerequisites for radical action and change, namely to be able to produce new knowledge, in contradistinction to self-replicating discourses. Not having had the luxury of resting well with conventional meanings, Black musical aesthetics continue to be necessary for clarifying the sociohistorical and racial contexts that make modernist crisises of referentiality so salient (Best 2018; Moten 2018; Gilroy 1995).

Elsewhere I have discussed the elision of jazz drummers’ epistemic contributions within the context of modernist aesthetics and critical theory (Kronfeld 2019, 2025). But as Samuel A. Floyd, Jr. reminds his readers in The Power of Black Music, “Rhythms… are not solely situated within the confines of drums” (Floyd, 2017: xxvi). Here I focus on the rhythmic contributions of pianists in order to de-essentialize the rhythmic imaginary while simultaneously emphasizing time’s primacy as jazz’s most salient text. These pianistic traditions can be seen as the afterlife of those “other percussive devices” named by Baraka in the wake of the criminalization of the drums and their communicative power (Baraka 1963: 27). In what follows, I draw on theorizations of swing by Louis Armstrong, Thelonious Monk and Georgia Anne Muldrow, and of the blues by James Baldwin and Ahmad Jamal.

It bears reminding here that rhythm qua aesthetic dimension provides space for the recovery of past forbidden, as well as the discovery of new, not-yet-available concepts, for past/future thoughts not yet thinkable (cf. A. Davis 1997: 163-64). This emphasis on process carries affinities both with Frankfurt School aesthetics (Kaufman 2005, 2000) and with Brenda Dixon Gottschild’s characterization of Africanist aesthetics (Gottschild 1996; Love 2021); but it also sets into sharp relief the divergences between these critical traditions. Angela Davis navigates this critical juncture between Frankfurt School and Black aesthetics in her Blues Legacies and Black Feminism, which remains ever salient: “My use of…the aesthetic dimension rejects its association with ‘transhistorical,’ ‘universal’ truths. I propose instead a conceptualization of ‘aesthetic dimension’ that fundamentally historicizes and collectivizes it.” (A. Davis 1997: 164). In a section from her Billie’s Bent Elbow (2025) entitled “Aesthetic Form in the New Thing,” Fumi Okiji draws a distinction between aesthetic form and musical form: “aesthetic form is ultimately processual even when it is encountered in the objectified work thing” (84). Okiji continues: “Aesthetic form is as much the means toward our congregating in performance or rehearsal, practice, or listening as our (co)habitation of musical space is the means to aesthetic form” (85).[3]

The potentialities that swing encodes in jazz and Black music more generally are never finished being known, rendering them answerable to unforeseen future circumstances, as well as to past and present experiences that have been occluded from view by structures of oppression, domination and appropriation (Okiji 2025, Kronfeld 2025). As jazz musicians have always taught, the innovative spatio-tempo/ral building blocks of Black music are attuned to the now precisely by virtue of being historically saturated, encoding what Georgia Anne Muldrow calls “new paths of articulation” (pers. comm 2023; cf. Ramsey 2004; Floyd 1996). [4]

Think of the way that Thelonious Monk’s rhythmic phrasing disrupts racialized aesthetic conventions of beauty qua the “pleasant” or “agreeable” while opening new, disruptive possibilities within the beautiful, what Monk called “ugly beauty” (Monk 1968). It is, in fact, this capacity for disruption that is beauty’s philosophical legacy (Ginsborg 2015, Moten 2017). In the process of his simultaneous rejection and illumination of the beauty ideal, Monk repurposes and radicalizes Charles Baudelaire’s postromantic metaphor in Les fleurs du mal (Baudelaire 1994 [1857]).

It is crucial to theorize from what rhythm artists say and do before “applying” theory to them (Defrantz 2001:43). As Dizzy Gillespie maintains in Notes and Tones, the landmark musician-to-musician collection of interviews, the history of Black music in recorded form – the sound – ought to be the primary text of jazz studies: “We are documented in records, and the truth will stand” (A. Taylor 1977:127). That primary text can be fruitfully interpreted and put into dialogue with any number of theoretical frameworks – if, that is, the sonic text itself has not been erased by being conflated ontologically with its transcriptions.[5] Increasingly, as musician-educators around the world can attest, jazz theory and even the widely-circulating jazz transcriptions of recorded standards and original compositions (e.g., The Real Book) not only pre-empt but often replace entirely the listener’s (and musician’s!) direct encounter with the musical text itself, cancelling out the epistemic interventions embedded within rhythmic, harmonic and melodic form.[6] This has created an unhappy correspondence between what Barbara Christian called “The Race for Theory” and the racist exclusion of the musicians from the study of the music (Christian 1987).

So what does it mean to theorize new categories from Monk, from Ahmad Jamal, etc.?

Let’s attune ourselves to the new forms of knowledge embedded, for example, in the first bar of Monk’s twelve-bar blues “Straight No Chaser.” One aesthetic theory perspective here might see Monk as producing inchoative knowledge (knowledge-in-process), or as engaged in a negative mimesis that encodes the violent attempts at the erasure of earlier Afrodiasporic rhythmic traditions of communication (Adorno 1997; for critiques see Okiji 2018 and Kronfeld 2019).[7] But does this sit comfortably with the epistemic theories embedded within Monk’s left hand and the traditions it both registers and transcends? In contradistinction and perhaps even in challenge to the interpretive framework of inchoative knowledge that I have gestured at above, the term jazz musicians often use for what the music offers –without invoking the usual positivist-empiricist baggage – is information. More accurately, the positivist-empiricist connotations of the term are both ironized and re-signified. This is how pianist Fred Hirsch, quoted in Paul Berliner (1994) puts it: “A Charlie Parker tune like ‘Confirmation’ should give you information” (231). And Amiri Baraka explains, invoking a Black Music epistemology that dismantles the alienating distinction between life and art: “Music is a living creature…The sounds carry whatever information rests in those frequencies and rhythms and harmonies” (Baraka 1996:141).[8] As Monkish re-imaginings and critical analyses by contemporary pianists continue to attest, the beginning of “Straight No Chaser” is replete with information (Jason Moran 2015; Eric Reed 2011; Fred Hirsch 1998). On the 1960 recording of “Straight No Chaser,” there is a flat-9 (a B-natural in the key of Bb) in Monk’s left hand that destabilizes the later oversimplified popular reception of the tune (listen to the accents at 0:00, 0:02, 0:08 and 0:13). Monk sounds like he is playing a G, Ab and a B-natural – the kind of “closed-position voicing” with a minor-second interval on the bottom that Robin D. G. Kelley rightly characterizes as a Monkish signature (R.D.G. Kelley 1999). As I have described elsewhere (Kronfeld 2021), the kind of listening that jazz practitioners engage in often runs counter to what Monk disciple Steve Lacy once described as “the bad habit of thinking in chords” (Eiland 2019, 95; R.D.G. Kelley 2009: 291).[9] Now, I love chords as much as the next piano player, but I understand why they have come to represent a characteristically American paint-by-numbers epistemology.[10] The “chord” applied as a pre-conceived, static generality (as in “Oh, just play a Bb7 chord in the first bar of ‘Straight No Chaser’”) risks obscuring the singularity of these notes, these intervals and voicings that need to be given credence and discrete attention. A Monkish theory of knowledge warns against allowing a pre-determined category to co-opt or occlude what’s in front of us. It may not be too much to read this as an allegory against white supremacy that is embedded in jazz listening practice – and offered to all listeners.

Just as Monk’s harmony requires unlearning the “bad habit of thinking in chords,” fully internalizing his rhythmic language calls for acquiring a new episteme, even as this language in turn sets the terms for basic fluency after Monk. Prof. Thomas Taylor, who instructs his drum students to study Monk’s piano comping, describes the studious listening required for such language acquisition when it comes to Monk’s rhythm: “If you haven’t listened to this 200 times, you don’t know it. And 200 is actually really on the short end.” [11] Even Miles Davis famously commented that it took him ages to properly learn “Round Midnight”: “I used to ask [Monk] every night after I got through playing [‘Round Midnight’], ‘Monk, how did I play it tonight?’ And he’d say, looking all serious, ‘You didn’t play it right.’ The next night, the same thing and the next and the next and the next” (M. Davis 1989: 78).

In the piano intro to “Straight No Chaser,” before being joined by the rest of the band, Monk plays through one chorus (12 bars) of the melody (from 0:00 to 0:14). Monk’s left-hand chord (a cluster more than a chord), with its modernist flat-9 harmonic intervention expressed as if it were a simple statement, alternately reinforces and plays off of the right hand’s melody by first accenting beat 1, then the “and” of beat 2, then beat 1 again, then beat 4, then the “and” of beat 4, then beat 2, then beat 2 again, finally landing on the “and” of beat 2. Thomas Taylor observes about Monk’s spatialization of rhythm: “He is a master at playing in unpredictable places. So unless you really know this version, you won’t ever put your left hand where he’s playing. It is as if Monk is doing an exercise where he plays every possible beat, but you don’t know which will come when.”[12] The spaces generated in between the accents are, of course, a crucial component of the rhythmic structure. John Edgar Wideman writes, letting his own elisions do the talking: “Silence one of Monk’s languages, everything he says laced with it… An extra something not supposed to be there, or an empty space where something usually is” (Wideman 1999: 551; cf. Sawyer 2025; Holiday 2023; Moran 2015). After this Intro, Monk plays the changes under “Straight No Chaser”’s melody in a more conventional way. But because we have become attuned to those dissonant clusters and accents in the Intro, now the expected itself sounds unexpected (T. Taylor, pers. comm. March 2, 2025).

From a drummer’s perspective, Thomas Taylor criticizes the overwhelming tendency to flatten out Monk’s rhythmic concepts. Take Monk’s comping under Charlie Rouse in “Bright Mississippi,” for example. The bouncing right-hand figure that Monk plays high up on the piano in response to the melody is neither swung eighth notes, nor straight eighths, nor triplets. “Maybe they are triplets that get slower, stretched and straighten out,” offers Taylor. The drummer’s perspective demonstrates the inchoative, in-process forms that real rhythmic concepts take – as opposed to the cookie-cutter molds and oversimplifying labels that prevent such rhythmic phrases from being heard accurately.

The very idea that harmonic analysis can be pursued independently of rhythmic phrasing is one of the fallacies that we need to shine a light on, and it’s a deeply ingrained problem in institutionalized jazz pedagogy (Murray 2017: 118; Wilf 2014; McMullen 2021; Baraka [Jones] 1967). Monk’s swing is the refutation of the “straight” in his title “Straight No Chaser” – even and especially when the left-hand harmonic accent lands squarely on the 1 –akin to what Amiri Baraka calls a “negation of a negation” (Baraka 1996: 22). Thus, it is not just that Monk swings what is straight, but rather that his rhythmic phrasing undoes the binary between swung time and straight time. As composer Anthony Kelley (pers. comm., May 6, 2023) pointed out to me, Monk’s composition “Misterioso” and its left-hand phrasing is an excellent example of the way in which the straight is also swung—is in effect reclaimed by swing as a parody of rigid conventionality. (Monk 2012 [1958]; A. Kelley 2024).[13] Monk shows the connection between rhythmic syncopation and harmonic dissonance. They operate in tandem. Rather than taking for granted syncopation as rhythm manqué (displaced rhythm; rhythm ‘minus’ something), Monk’s polyrhythmic vernacular lays bare the distortion that results from the presupposition that something called “straight time” is primary. As saxophonist Howard Wiley suggests, the construct of syncopation itself is perpetually in the process of being freed by its practitioners, although, by the same token, this generates the ever-present danger that it can be “‘taken back’ [by hegemonic powers] at any time” (Wiley, pers. comm, 2019; Kronfeld, 2019: 35)[14].

Just as Morrison rhetorically asks in relation to Ralph Ellison’s novel—“Invisible to whom?”, one may ask about Monk’s fame for his off-beat syncopations—syncopated to whom?[15] In other words, what is perfectly logical, to quote Monk himself (Kelley 2009, 2020), only appears as a deviation when going out of one’s way to negate and ignore the epistemologies embedded in Black Musical Space (in James Gordon Williams’ terms; Williams 2021). Thus, contrary to popular belief, what makes jazz unpredictable is precisely what makes it a language (cf. Moten 2018 on Chomsky 1986). Monk’s unpredictability becomes the language one needs to know. Monk’s swing is the refutation of the “straight” in his title “Straight No Chaser” – even and especially when the left-hand harmonic accent lands squarely on the 1 –akin to what Amiri Baraka calls a “negation of a negation” (Baraka 1996: 22).

I center Monk in the context of this issue on R(hy)pistemologies because Monk’s rhythmic prowess on the piano has been vastly underacknowledged by critics.[16] To put it bluntly, Monk’s harmonic interventions have fit more comfortably within modernism as it is traditionally construed than has his sense of rhythmic groove, swing and danceability.[17] In contrast, Robin D.G. Kelley offers a key discussion of the racial politics of “swing” and their impact on Monk’s conditional acceptance into the avant-garde (RDG Kelley 1999:52). Indeed, musicians have always emphasized the primacy of Monk’s time.[18] James Gordon Williams writes that Monk “encapsulated Black musical space” (Williams 2021: 15). Williams describes the profound impact of Monk’s teaching on the master drummers of his generation and after: “From Monk, [Billy] Higgins received observational lessons about space and time” (Williams 2021:54). Williams “view[s] African American improvisation as a deployment of oppositional spatial knowledge that reflects the material conditions and imaginations that shape Black lives on a daily basis” (Williams 2021: 9). Williams’ theorization of “musical place-making,” the improvisational mapping, even the “spatial insubordination” of Black music draws on Katherine McKittrick’s Black Geographies and bell hooks’ “radical creative space” (Williams 2021:6). The black sense of place reflected and generated in “African-American improvisatory and compositional practices” both indexes and calls into question the “spatial domination” and “hegemonic spaces that have displaced Black people” (Williams 2021:6-8).[19] Black musical space becomes especially salient in the context of policing and the racialized state violence inflicted on Monk himself.[20]

In his solo piano recording of “Evidence” (Monk 1954). Monk’s rigorous implication of the “one,” [i.e. beat 1], evoked via negation, becomes particularly salient.[21] A complete rhythm section unto himself, Monk breaks the silence on the “and” of beat 1, opening up the possibility of a half-time feel – the kind of implied time that evokes the clave and a whole past and future of progressive Afro-Cuban music. As is well known, Monk’s composition was based on the standard tune “Just You Just Me,” which he later retitled “Justice” spelled “JUST – US” – an ironic criticism of the Justice that is “just” for the racially unmarked (Edwards 2001; Leal 2023). His new title, “Evidence” takes apart rhythmically the feigned coherence of dominant evidentiary norms.[22]

But Monk’s use of time and rhythmic form, as we have seen, also points—both ways, as it were—to past and future transnational developments within Black American music from timba to funk to R&B and hip-hop. Here is Miles Davis in 1989:

I think a lot about Monk these days because all the music that he wrote can be put into these new rhythms that are being played today by a lot of young musicians – Prince, my new music… a lot of his music reminds me of the West Indian music being played today”… You could adapt some of his music to what’s going on now in fusion and in some of the more popular veins; maybe not all of them, but the ones that got the pop in the motherfucking head, you could. You know, that black rhythmic thing that James Brown could do so good, Monk had that thing and it’s all up in his compositions (80).

Davis’ remarks toward the end of his life foreshadow emerging theoretical paradigms drawing on Black musical aesthetics in recent years to theorize non-linear, trans-generational temporality (Okiji 2017; Sawyer 2025). They also resonate with recent intergenerational jazz practice by contemporary drummers like Kendrick Scott, who during COVID organized thirty-eight drummers to perform a virtual communal version of Monk’s “Evidence” (Scott 2020).[23]

In my dialogue with Michael J. Love about this, inspired by Love’s own work on the marginalization of the rhythmic vernacular within contemporary dance, I shared that an issue closely related to Monk’s often misunderstood rhythmic syncopation are the “grace notes” that are often illegible because they are taken as mistakes and sometimes kept out of the transcriptions, rather than attended to in their complexity as being where the music is actually happening.[24] This has to do with the idea that the rhythmic vernacular is the core text; but as Love has shown, drawing on Brenda Dixon Gottschild, it is precisely this Africanist dimension that is repressed (Love 2021, Gottschild 1996). Love and I have both witnessed with frustration from the dance and piano sides of jazz performance that in mass culture, extensive, convoluted maneuvers are often performed to avoid acknowledging the existence of Afrodiasporic rhythmic intelligence on its own terms.

In his important but still underappreciated 1936 philosophical monograph on the music of the Harlem Renaissance, Alain Locke writes that “jazz is in constant danger” from commercialization (Locke 1936: 174). In fact, this is one of the main preoccupations of his book on the Black music of his time (Porter 2002:45-47).[25] Locke quotes at length from Louis Armstrong’s own book Swing that Music, which was also published in 1936. Armstrong’s Swing that Music has frequently been mistaken for “mere” biography or memoir, rather than offering the radical theoretical and historiographical critique of the music that he in fact contributes in this work (Veneciano 2004: 272; O’Meally 2022). Armstrong writes: “The reason swing musicians insist upon calling their music ‘swing music’ is because they know how different it is from the stale brand of jazz they’ve got so sick of hearing. But in the early days, when jazz was born, jazz wasn’t that way at all… We can now look back [remember, he is saying this in 1936!] and see where jazz got side-tracked. We won’t have many excuses… if we let today’s swing music go the same way” (Armstrong 1993 [1936]:122, qtd. in Locke 1936: 110). Armstrong anticipates the critical stance Baraka takes as LeRoi Jones in his 1963 Blues People in the chapter “Swing: From Verb to Noun,” where the noun is the grammatical correlate of reification. But already for Armstrong, “swing music” is itself the name of the attempt to wrest jazz back from the co-opting forces that dilute it and threaten its newness. Margo Natalie Crawford’s readings of “anticipatory, liminal” texts of the Harlem Renaissance provide an important context for Armstong’s observations. Crawford demonstrates that Langston Hughes and Zora Neal Hurston “anticipate” (a technical notion Crawford imbues with both historiographical and rhythmic aesthetic valences) the Black Arts Movement in their trenchant critiques of black music’s commercialization (Crawford 2017).[26] Enriching the dialogue with the verbal art of his day, Armstrong draws an analogy in Swing that Music between the linear plots of pulp fiction and the commercialized versions of jazz. He writes: “I do know that a musician who plays in ‘sweet’ orchestras must be like a writer who writes stories for some popular magazines. He has to follow along the same kind of line all the time” (29). Armstrong continues: “[The conventional writer] has to write what he thinks the readers want just because they’re used to it. But a real swing musician never does that” (29). He speaks here from the center of the Afromodernist call for experimental renewal, for a novel musical language that will continually resist the stultifying linear progressions demanded by white commercial markets.

After drawing on Louis Armstrong’s critical poetics of swing, there is another artist Alain Locke specifically identifies as being able to preserve his art in an unadulterated way – Jimmie Lunceford. In the 1935 recording entitled “The Melody Man” (Lunceford 1935) you can hear a syncopation that evades capture. Propelled by drummer Jimmy Crawford’s brushes, the tightness between the horns and rhythm section prefigures James Brown’s band. I take this to be an example of the swing under the swing that continues to inform contemporary creative practice.

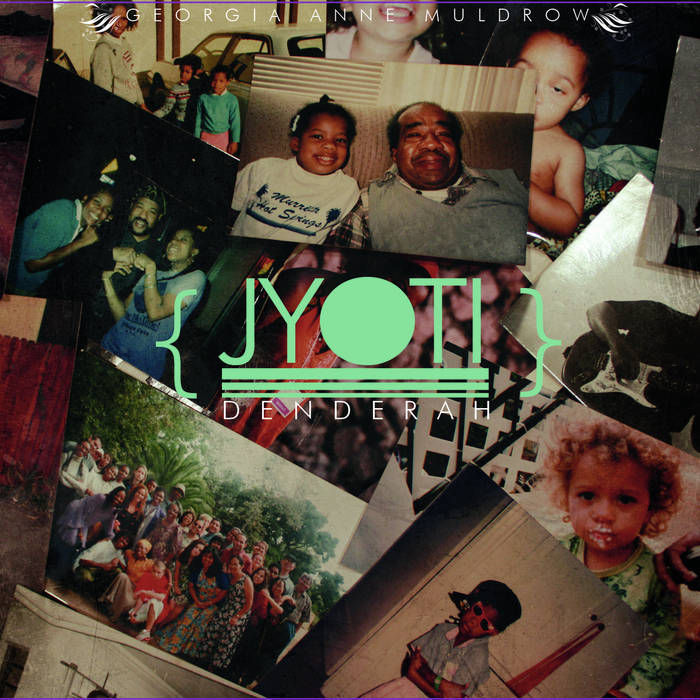

Mama, You Can Bet! (2020); Denderah (2013). Written, produced, arranged & performed by Georgia Anne Muldrow.

Georgia Anne Muldrow (b. 1983) is a composer, multi-instrumentalist and producer whose works brings together rhythmic and harmonic innovation, new epistemologies, and community-based activism. She recorded the 2013 album Denderah and the 2020 Mama, You Can Bet! as Jyoti, the pseudonym given to her by Alice Coltrane and reserved for what Muldrow calls her “one-woman jazz ensemble.” Here, as on all her studio albums, Muldrow plays every instrument. On Denderah’s fourth track, “Sup,” which echoes the BPM (beats per minute, or tempo) of “Melody Man,” listen for the drum language of the brushes – done on synthesizer. Muldrow is taking apart the syncopation even further. Peeling back the swing behind the (co-opted) swing, she layers her brushes over existing syntax of the 1920s and 30s, disclosing that era’s own repudiation of the commercialized “pulp fiction” music diagnosed by Louis Armstrong. Her brushwork on synthesized drums here illustrates the avant-garde reach of both past and present: “The syntax is there for you to be able to create a new path of articulation, but there always comes a time when it comes back to where it began” (Muldrow, pers. comm, October 30, 2023).

Georgia Anne Muldrow with Maya Kronfeld on keyboards as part of Justin Brown’s NYEUSI. 2018 Nublu Jazz Festival at SESC Pompeia in São Paulo, Brazil. Featuring Josh Hari, Chad Selph, Nadia Washington, Jaime Woods, Josh Hari. Photo courtesy of the author.

This intergenerational focus on rhythm lays bare the shortcomings of critical discussions of improvisation that center exclusively on melodic instruments, rather than on rhythm section instruments (drums, piano, bass) in their rhythmic functions. These trends are related to the willful misperception that blues is merely jazz’s more simple precursor, an erroneous historiography that is all too often used to justify the exclusion of Black artists and teachers from educational spaces. Counteracting these tendencies, Rhonda Benin reminds us in her vocal performance course of the same name that “Jazz Ain’t Nothing but the Blues” (Benin 2024). Benin, a vocal artist-educator and member of the Linda Tillery Cultural Heritage Choir makes clear that Blues as avant-garde roots music is precisely jazz’s chief template for ongoing revision, mutation and innovation (Tillery 1999, 2014; cf. Hunter 1998).

In James Baldwin’s essay “On the Uses of the Blues” (1964), he argues that black music is engaged in a form of direct truth-telling that makes good on the very communicative function that hegemonic language has abandoned. Baldwin makes the surprising move of correlating blues singer Bessie Smith with fiction writer Henry James, arguing that both artists fulfill the promise of creating non-reductive, non-deadening knowledge in a dominant culture whose expertise lies in the “distinctly American inability (like a frozen place somewhere)…to perceive the reality of others” (Baldwin 1986: 14). This provocatively interracial, trans-disciplinary rewriting of the American canon is based on black music as the irreplaceable model for truth-telling (“information” in the language of jazz artists) in a culture of evasion and denial. Baldwin writes: “‘Gin House Blues’ is a real gin house. ‘Backwater Flood’ is a real flood. This is what happened, this is what happened, this is what it is” (59). Baldwin’s own rhythmic reiteration asks us to grapple with the idea that the blues song is a real gin house, rather than a reference to one—flying in the face of the sacrosanct use-mention distinction in Anglo-American analytic philosophy of language (Cappelen, Herman, Lepore, & McKeever, 2023). But we can correlate Baldwin’s astonishing claim (his subsumption of the mere mention of the blues to the uses of the blues) with an idea shared across Frankfurt School and Afro-modernist aesthetics that art works, particularly in social contexts of violent erasure, must embody rather than describe (M. Davis 1998; Kaufman 2005). Baldwin’s twist, however, is to insist on the primacy of these acts of artistic embodiment, claiming—from the standpoint of Black music—that the possibility of literal truth-telling hinges on such artistic acts.

The modernist trope of exhaustion with available descriptions is greatly clarified by its Black critique of referentiality. But this critique is only possible thanks to the complex legacies of Black rhythmic forms in the music itself, legacies which are still often feared by and excluded from academically-codified philosophical aesthetics (and we can argue, are not fully theorized even in Baldwin’s essay, where discussions of lyric and lyricization are most prominent).

Baldwin’s own use of “the blues” would have been invoking a holistic notion of the oneness of Black music (Wiley, pers. comm. May 15, 2009) that even now emphasizes the continuities among and between jazz, blues, gospel, R&B, funk, hip-hop and even those genres later coded as white, such as rock n’ roll and punk. Genre distinctions between jazz and blues are widely regarded among practitioners of the music as artificial, and too often marshalled to perform a colonizing function (Baraka 1963). I’ve suggested that Black music according to Baldwin catalyzes the modernist critique of descriptive, propositional knowing. At the same time, however Baldwin also calls into question Kantian/Frankfurt School notions of aesthetic autonomy by insisting on the claim that in a coercive society, Black music is literal description.

The salience of rhythm in the U.S. and other regions of the African diaspora is due not only to the textural – and indeed textual! – richness and complexity of Black rhythmic forms but also to the systemic racism that has prevented descriptive content from being encoded in other channels; for example, in the lyrics, as Tyfahra Singleton has shown (Singleton 2011). James Baldwin writes: Americans are able to admire Black music only to the extent that “a protective sentimentality limits their understanding of it” (Baldwin 1951; my emphasis). And what is being protected, he’s saying, is the white sense of self. The sentimental in American culture, we might say, is a defense against the tragic and the critical.

As a closing counterpoint, I’d like to offer an example from Ahmad Jamal’s album Happy Moods (Jamal, 1960). I’ve selected the track “Excerpts of the Blues” because we are often taught harmony on the model of a binary cliché between major chords as happy and minor chords as sad; but applying that false binary to the blues make the innovations of the blues form illegible (recall that Monk’s “Straight No Chaser” is also a blues!) The blues take us behind that notion of major as opposed to minor thirds, but more importantly, they take us beyond the emotional binaries that Baldwin diagnoses as so uniquely American, where “happiness” is a vapid, saccharine substitute for real joy. This is what makes Ahmad Jamal’s Happy Moods so interesting. In the piece entitled “Excerpts from the Blues,” Jamal demonstrates that major seven chords are part of the blues (whereas in codified jazz pedagogy, blues harmony is most frequently associated with dominant-seven chords). This then becomes a point of departure for other colors and hues, as when he lets C major 7 (the piece’s tonic or “home” key) get inflected by its minor 4 (F minor). Like Monk’s swinging of straight time, Jamal reclaims this major 7 sound not as empty optimism but as containing within it all the emotional complexities of the blues. The form of the composition itself holds all that together: the A section is built on a 1 chord that is a major seven; then the B section is a traditional blues as we might expect it to be, based on the dominant sound.

Every bar of “Excerpts of the Blues” is a masterclass; indeed, it is sometimes observed that one bar of Ahmad Jamal contains within it the whole future of recorded music. I have created a two-bar loop out of the material from 0:11-0:14, which I have notated (imperfectly!) as a bar of 4/4 followed by a bar of 2/4. At the “(Rhy)pistemologies: Thinking Through Rhythm” Conference, I improvised on the piano along with this six-beat loop, joined by Paris Nicole Strother, founder of the group We Are KING.[27]

Along with trio mates Israel Crosby on bass and Vernel Fournier on drums (brushes), Ahmad Jamal expands existing concepts of rhythm and harmony, but does so out of a capacious sense of spaciousness. The array of interlocking parts means that it’s never just one thing. There is 1) the relationship between the drums and bass; 2) the relationship between Jamal’s two hands at the piano (note the unexpected accent on the triplet in the left-hand chord just as the harmony darkens and deepens); 3) the change in rhythmic feel within a single line in the right hand, where Jamal’s melodic phrase switches mid-stream from triplet time (swung) to march time (straight), and back again. With Ahmad Jamal, you feel the “both/and” of it all. The trio is playing different facets of the blues simultaneously, just as Jamal himself is showing us so many different facets of the harmony and rhythm, all at the same time.

Many thanks to Thomas Taylor and Tobin Chodos for help with notation-interpretation.

References

Adorno, Theodor W. Aesthetic Theory, ed. Gretel Adorno and Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Armstrong, Louis. 1993 [1936]. Swing That Music. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press.

Atkinson,Daniel E. 2016. “‘Feets Don’t Fail Me Now”: Navigating an Unpaved, Rocky Road to, through and from the Last Slave Plantation’, in Civic Labours: Scholar Activism and Working-Class Studies, eds. Dennis A. Deslippe, Eric Fure-Slocum, and John W. McKerley. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Baldwin, James. 1986. Interview with David Adams Leeming. “An Interview with James Baldwin on Henry James,” The Henry James Review 8, no. 1: 47-56.

Baldwin, James. 2011 [1964]. “The Uses of the Blues.” In The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings, ed. Randall Kenan. New York: Vintage International.

Baraka, Amiri. [LeRoi Jones].1963. Blues People: Negro Music in White America. Wesport, Conn.: Greenwood Press.

Baraka, Amiri. 2009. Digging: The Afro-American Soul of American Classical Music. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Baraka, Amiri [LeRoi Jones]. 2010 [1967]. “The Changing Same (R&B and New Black Music).” In Black Music. New York: Da Capo Press.

Baraka, Amiri [LeRoi Jones]. 2010 [1963]. “Jazz and the White Critic.” In Black Music. New York: Da Capo Press.

Batiste, Jon. 2021. “Jon Batiste on THELONIOUS MONK: STRAIGHT, NO CHASER.” Turner Classic Movies: TCM. Juneteenth – 6/19. https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=868065477121956

Baudelaire, Charles. 1994 [1857/1869]. Flowers of Evil & Paris Spleen, trans. William H. Crosby. Rochester, NY: BOA Editions.

Benin, Rhonda. “Jazz Ain’t Nothing But the Blues.” The Jazzschool and California Jazz Conservatory. https://jazzschool.cjc.edu/event/jazz-aint-nothing-but-the-blues/ Accessed August 31, 2024.

Berliner, Paul. 1994.The Infinite Art of Improvisation. London & Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Best, Stephen. 2018. None Like Us: Blackness, Belonging and Aesthetic Life. Durham, NC.: Duke University Press.

Cappelen, Herman, Ernest Lepore, and Matthew McKeever. 2023. “Quotation.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, eds. Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman. <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2023/entries/quotation/>.

Carr, Raymond. 2023. “The Dancing Monk and the Rhythm of Divine Life.” Harvard Divinity Bulletin. https://bulletin.hds.harvard.edu/the-dancing-monk-and-the-rhythm-of-divine-life/.

Christian, Barbara. 1987. “The Race for Theory.” Cultural Critique 6: 51-63.

Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Knowledge of Language: Its Nature, Origin and Use. New York: Praeger.

Chow, Rey. 2010 [1998]. “The Postcolonial Difference: Lessons in Cultural Legitimation.” In The Rey Chow Reader, edited by Paul Bowman. New York: Columbia University Press.

Cobo-Piñero, Rocío. 2022. “Beyond Literature: Toni Morrison ‘s Musical and Visual Legacy for Black Women Artists.” Feminismo/s 40: 27-51.

Coleman, Kwami. “Free Jazz and the ‘New Thing’: Aesthetics, Identity, and Texture, 1960-1966.” The Journal of Musicology 38 no.3: 261-295.

Crawford, Margo Natalie. 2017. Black Post-Blackness: The Black Arts Movement and Twenty-First Century Aesthetics. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Davis, Miles. With. 1989. Quincy Troupe, Miles: The Autobiography. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1989.

Davis, Angela Y. 1998 Blues Legacies and Black Feminisn: Gertrude “Ma”Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday. New York: Pantheon Books.

Davis, Eisa. 2025. The Essentialisn’t (paperback). New York: Theatre Communications Group.

Defrantz, Thomas F. 2001. Dancing Many Drums: Excavations in African American Dance. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Deveaux, Scott. 1999. “The Jazzman’s True Academy.” In Bebop: A Social and Musical History. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 202-235.

DiPiero, Dan. 2021. “Race, Gender, and Jazz School: Chord-Scale Theory as White Masculine Technology,” Jazz and Culture 6, no.1: 52-77.

Dunning, Jennifer. 1985. “DANCE REVIEW; 3 Icons Exploring Life’s Horrors and Joys.” The New York Times, July 27.

Eiland, Howard. 2019. Notes on Literature, Film and Jazz. New York: Spuyten Duyvil.

Edwards, Brent Hayes. 2001. “Evidence.” Transition, no. 90: 42-67.

Feurzig, David. 2011 “The Right Mistakes: Confronting the ‘Old Question’ of Thelonious Monk’s Chops.” Jazz Perspectives 5, no. 1: 29-59.

Floyd, Samuel A., Jr. with Melanie L. Zeck and Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr. 2017. The Transformation of Black Music: The Rhythms, the Songs, and the Ships of the African Diaspora. Oxford: Oxford University, Press.

Floyd, Samuel A. The Power of Black Music: Interpreting its History from Africa to the United States. 1996. Oxford: Oxford Universeity Press.

Gilroy, Paul. 1995. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double-Consciousness. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Gottschild, Brenda Dixon. 1996. Digging the Africanist Presence in American Performance: Dance and Other Contexts. Westport, Connecticut & London: Praeger.

Greenfield-Sanders, Timothy. 2019. Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am. Magnolia Pictures.

Hirsch, Fred. 1998. Thelonious: Fred Hirsch Plays Monk (Nonesuch).

Haywood, Mark S. “Rhythmic readings in Thelonious Monk” Annual Review of Jazz

Studies 7, (1994-1995): 25-45.

Holiday, Harmony. “The Fraught Dance Between Artist and Interviewer in ‘Rewind & Play.’” March 18 2023. The New Yorker.

Hunter, Tera. 1998. To ’Joy My Freedom: Southern Women’s Lives and Labors After the Civil War. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Jamal, Ahmad. 1960. Happy Moods. Argo

Kaufman, Robert. 2000. “Red Kant, or the Persistence of the Third Critique in Adorno and Jameson.” Critical Inquiry 26, no. 4: 682-724.

Kaufman, Robert. 2005. “Lyric’s Expression: Musicality, Conceptuality, Critical Agency.” Cultural

Critique 60: 97-216

Kelley, Anthony. Interview with Jerad Walker, Anisa Khalifa, and Charlie Shelton-Ormond. 2024. “The Hunt for a Long-Lost Musical Masterpiece.” WUNC Radio, May 30. https://www.wunc.org/podcast/the-broadside/2024-05-30/mary-lou-williams-jazz-history-duke-anthony-kelley

Kelley, Robin D. G. 1999. “New Monastery: Thelonious Monk and the Jazz Avant-Garde.” Black

Music Research Journal 19, no. 2: 135-168.

Kelley, Robin D.G. 2009. Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original. New York: Free Press.

Kelley, Robin D.G. 2020. “‘Solidarity Is Not a Market Exchange’: An Interview with Robin D.G. Kelley.” BLACK INK. https://black-ink.info/2020/01/16/solidarity-is-not-a-market-exchange-an-interview-with-robin-d-g-kelley/

Kronfeld, Maya. 2019. “The Philosopher’s Bass Drum: Adorno’s Jazz and the Politics of Rhythm,” Radical Philosophy 205: 34-47.

Kronfeld, Maya. 2021. “Structure in the Moment: Rhythm Section Responsivity.”

Kronfeld, Maya. 2025. “Spontaneity.” In Political Concepts: A Lexicon 7. Literature Edition. https://www.politicalconcepts.org/category/issue-7/

Kronfeld, Maya. 2025. “The Indispensability of Form: A Kantian Approach to Philosophy and Literature.” In The Cambridge Companion to Philosophy and Literature, eds. Lanier Anderson and Karen Zumhagen-Yekplé (in press).

Lacy, Steve. 2006. “Steve Lacy Speaks,” interview with Paul Gros-Claude, in Steve Lacy: Conversations, ed. Jason Weiss. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Leal, Jonathan.2023. Dreams in Double Time: Refiguring American Music. Durham: Duke University Press.

Lewis, George E. 2002. “Improvised Music After 1950: Afrological and Eurological Perspectives.” Black Music Research Journal 22: 215-246.

Locke, Alain. 2022. The New Negro Aesthetic: Selected Writings, eds. Jeffrey C. Stewart and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. New York: Penguin Classics.

Locke, Alain. 1936. The Negro and His Music. Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Press.

Love, Michael J. 2021. “’Mix(tap)ing’: A Method for Sampling the Past to Envision the Future,” Choreographic Practices, 12:1 (March 2021): 29-45

Lunceford, Jimmie. 1935. “The Melody Man.” The Complete Jimmie Lunceford Decca Sessions (Mosaic)

McMullen, Tracy. “Jazz Education After 2017: The Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice and the Pedagogical Lineage.” Jazz and Culture 4, no. 2 (2021): 27–55.

McPherson, Jadele. 2025. “Fugitive Acts: One Hundred Years of Afro-Cuban Performance,” in “Overcoming the Difficulty: The Racial and Gender Politics of Cuban Performance in Tampa.” PhD Dissertation, CUNY Graduate Center.

Monk, Thelonious. 1968. “Ugly Beauty.” Underground (Columbia Records).

Monk, Thelonious. 1954. “Evidence.” Piano Solo (Disques Vogue).

Monk, Thelonious.2012 [1958]. “Misterioso.” Misterioso (Concord).

Moran, Jason. BlindFold Test with Dan Ouellette. Downbeat April 2018.

Moran, Jason. 2015. In My Mind: Monk At Town Hall, 1959. Jazz Night in America. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2015/10/08/446866440/jason-moran-plays-thelonious-monks-town-hall-concert

Morrison, Toni. 1998. Paradise. New York: A. A. Knopf.

Moten, Fred. 2018. Stolen Life, vol. 2 of consent not to be a single being. Durham, NC.: Duke University Press.

Moten, Fred. 2017. Black and Blur, vol. 1 of consent not to be a single being. Durham, NC.: Duke University press.

Muldrow, Georgia Anne. 2023. Author Interview, Durham, N.C., October 30.

Muldrow, Georgia Anne [as Jyoti]. 2020. Mama, You Can Bet! (SomeOthaShip Connect).

https://someothaship.bandcamp.com/album/mama-you-can-bet

Muldrow, Georgia Anne [as Jyoti]. 2013. Denderah (SomeOthaShip Connect).

https://someothaship.bandcamp.com/album/denderah

Murray, Albert. 2017 [1976]. Stomping the Blues. 40th Anniversary Edition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Okiji, Fumi. 2018. Jazz as Critique: Adorno and Black Expression Revisited. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Okiji, Fumi. 2017. “Storytelling in Jazz Work as Retrospective Collaboration.” Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Okiji, Fumi. 2025. Billie’s Bent Elbow: Exorbitance, Intimacy, and a Nonsensuous Standard. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press

O’Meally, Robert G. 2022. Antagonistic Cooperation: Jazz, Collage, Fiction and the Shaping of African American Culture. New York: Columbia University Press.

Prouty, Kenneth E. “The History of Jazz Education: A Critical Assessment.” Journal of Historical Research in Music Education 16, no. 2.

Ramsey, Guthrie P. 2004. Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop. Berkeley, CA.: University of California Press.

Ratliff, Ben. 2016. “Review: ‘We Are King,’ With Its Deep R&B Strategies, Is a Musicians’ Album.” February 13. New York Times.

Reed, Eric. 2011. The Dancing Monk (Savant).

Reed, Anthony. Soundworks: Race, Sound, and Poetry in Production. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Sawyer, Michael. 2025. “So What: Kind of More or Less Than All Blue(s).”Boundary 2 Online. Special Issue: “(Rhy)pistemologies: Thinking Through Rhythm.”

Sawyer, Michael. 2025. The Door of No Return: A Phenomenology of Black(ness). Forthcoming.

Singleton, Tyfahra.2011. “Facing Jazz, Facing Trauma: Modern Trauma and the Jazz Archive.” Ph.D. diss., UC Berkeley.

Somers, Steven. 1988. “The Rhythm of Thelonious Monk,” Caliban 4: 44-49.

Taylor, Art. 1977. Notes and Tones: Musician-to-Musician Interviews. New York: Da Capo Press.

Taylor, Thomas E., Jr. It’s All About the Ride! The Ride Cymbal and Snare Drum Book. Forthcoming, 2025.

Taylor, Thomas E., Jr. “Comping With Miles and Wynton.” Jazz Drummers’ Workshop. Modern Drummer 285 (Aug. 2003): 94-96. https://www.moderndrummer.com/article/august-2003-volume-27-number-8/

Tillery, Linda. 1999. Oral History Interview with Linda Tillery. March 29. University of Denver. https://mediaspace.du.edu/media/Oral+history+interview+with+Linda+Tillery%2C+1999/0_vy0u97zv/168664692

Tillery, Linda. 2014. Interview: 2014 Community Leadership Awards. San Francisco Foundation. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CDyEJoR1zUI

“Toni Morrison/ Max Roach: Performance lecture et batterie.” Festival d’automne, archive. https://www.festival-automne.com/en/edition-1994/toni-morrison-max-roach-performance-lecture-batterie. Accessed August 31, 2024.

“Toni Morrison et Max Roach: la voix et le rythme.” 2020. Les Nuits de France Culture. https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceculture/podcasts/les-nuits-de-france-culture/toni-morrison-et-max-roach-la-voix-et-le-rythme-6555310April 18.

Veneciano, Jorge Daniel. 2004. “Louis Armstrong, Bricolage, and the Aesthetics of Swing.” In Uptown Conversation: The New Jazz Studies, edited by Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin.

Wideman, John Edgar. 1999. “The Silence of Thelonious Monk.” Callaloo 22, no. 3: 550-557.

Wiley, Howard. May 5, 2019. Personal Communication.

Wiley, Howard. 2019. The Angola Project, 12 Gates to the City. Compact Disc. https://www.discogs.com/release/10414938-Howard-Wiley-And-The-Angola-Project-Featuring-Faye-Carol-12-Gates-To-The-City?srsltid=AfmBOoqCHCqH4JKgIGmliHsr6t9dylE8TKgYmJFuortQWNDh2NLUpYnu

Wilf, Eitan Y. 2014. School for Cool: The Academic Jazz Program and the Paradox of Institutionalized Creativity. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Williams, James Gordon. 2021. Crossing the Barlines: The Politics and Practices of Black Musical Space. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi.

Wolfson, Susan and M. Brown, eds. 2000. Reading for Form. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Notes

* I am grateful to Erin Graff Zivin, Jonathan Leal, Michael J. Love, Paris Nicole Strother, Georgia Anne Muldrow, Thomas Taylor, Inger Flem and the participants of the “‘(Rhy)pistemologies’: Thinking Through Rhythm” conference at the USC Experimental Humanities Lab, and to Art Share Los Angeles. Special thanks to my longtime interlocutor, Michael Sawyer. Earlier drafts were presented at the 2024 ACLA in Montreal, and at the University of Pittsburgh, 53rd Annual Jazz Seminar. Special thanks to Aaron J. Johnson, Michael C. Heller, and Yoko Suzuki. My discussion of Ahmad Jamal here benefited from “Ahmad Jamal: In Appreciation,” moderated by Dr. Michael P. Mackey with panelists Dr. Alton Merrell, Dr. Nelson Harrison, and Judge Warren Watson. November 3, 2024. University of Pittsburgh Hill Community Engagement Center. I thank Stephen Best, Anthony Kelley, Philip Rupprecht, Davina Thompson and the two anonymous reviewers for valuable discussions and feedback. I would like to acknowledge my late father Amichai Kronfeld (ז״ל) for teaching me drum exercises before I could walk.

[1] Guthrie P. Ramsey discloses “the ways in which blackness troubles the disciplinary boundaries among the subfields of music scholarship” (Ramsey 2004: 19). See George E. Lewis on “an ongoing narrative of dismissal, on the part of many…composers, of the tenets of African-American improvisative forms” (2002:216). My participation in Eisa Davis’ sound-based conceptual art work “The Essentialisn’t” informs my thinking here. For full text see E. Davis 2025 . See also https://www.jackny.org/whats-on/the-essentialisnt-5 .

[2] Audio available via Les Nuits de France Culture 2020; cf. Cobo-Piñero 2022; Dunning 1995; Kronfeld 2024.

[3] Recall that Amiri Baraka insisted that the term “Aesthetic” in the “Black Aesthetic” is “useful only if it is not depoliticization of reference.” See Baraka’s 1989 essay entitled, “The ‘Blues Aesthetic’ and the ‘Black Aesthetic’: Aesthetics as the Continuing Political History of a Culture” (Baraka 2009: 9-28). He writes, “The Blues is not even twelve [bars] necessarily, the insistence on that form is formalism” (24). Baraka’s notion of “functional music” has offered a key challenge to reductively formalist paradigms of aesthetic autonomy (Baraka [Jones] 1963). For in-depth discussion of Baraka’s explicit and implicit poetics, see A. Reed 2021. Kwami Coleman illuminates the “ostensible [and ultimately untenable] wedge” in jazz criticism of the mid-60s “between writings on the avant-garde that focused on the music’s design and writings that addressed its social politics” (2021:268). The deeper readings of aesthetic form offered by Okiji and Davis all too often fell out of view in formalist criticism of the twentieth century and beyond. Kaufman (2000) and Wolfson (2000) critique and correct this reductive reception.

[4] Guthrie P. Ramsey, following Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., writes: “The process of repetition and revision that characterizes these musical styles shows how black musicians and audiences have continually established a unified and dynamic ‘present’ through music” (Ramsey 2004: 36; Floyd 1996). See Baraka, “The Changing Same (R&B and New Black Music)” (Jones 1967). For critical engagement with Baraka’s influential essay, see Ramsey 2004: 36.

[5] See Berliner (1994), DiPiero (2021), Lewis (2002), Monson (1996), Wilf (2014) for critical perspectives on the dominating “paper-based” approach. See Prouty (2005) for an illuminating study redressing the limits of “prevailing institutionally based narratives of jazz education’s history.”

[6] For an illustration via divergent interpretations of Monk’s “Round Midnight,” see DeVeaux 1999, 223-24. See Baraka as LeRoi Jones (1964) on the racial and epistemological problematics of notation when it comes to Monk’s and Louis Armstrong’s solos (14).

[7] For an account of embodied knowledges and Afro-diasporic rhythmic form that denies the success of such attempts at erasure, see McPherson 2025.

[8] See also Fumi Okiji’s discussion of Muhall Richard Abrams (Okiji 2018).

[9] See also pianist Barry Harris: “Coleman Hawkins would say, ‘I play movements; I don’t play chords’” (Harris 2011). https://tedpanken.wordpress.com/2013/12/15/its-barry-harris-84th-birthday-a-link-to-a-2011-post-of-a-downbeat-article-and-several-verbatim-interviews-conducted-for-the-piece/.

[10] See Lewis (2002). See DiPiero (2021).

[11] See the unprecedented article by Taylor in Modern Drummer featuring trumpet and piano transcriptions from Kind of Blue rendered for drumset, “Comping With Miles and Wynton” (T. Taylor 2003) and his forthcoming book, It’s All About the Ride!: The Ride Cymbal and Snare Drum Book (T. Taylor 2025). For further resources, see https://www.thomasdrum.com/teaching

[12] See Samuel A. Floyd: “In Monk’s playing, almost every event is unexpected” (Floyd 1995: 82)

[13] See Kronfeld, 2019. See also Kelley on his recent completion of Mary Lou Williams’ unfinished last work “History: A Wind Symphony,” performed by the Duke Wind Symphony on April 13, 2024. Interview in Walker, Khalifa and Shelton-Ormond, 2024

[14] For a major musical and ethnographic intervention in the historiography of swing, based on research at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, see Howard Wiley & The Angola Project, 12 Gates to the City, 2010, compact disc. See also Atkinson 2016.

[15] See Morrison’s challenge to Ralph Ellison: “Invisible to whom?” (Greenfield-Sanders 2019)

[16] In contrast, see Robin D. G. Kelley on Monk’s “rhythmical melodies” and his stride piano mastery, as heard from the perspective of Herbie Nichols (RDG Kelley 2009: 98-99). And see Somers 1988, Haywood 1994-1995.

[17] See R.D.G. Kelley 2009: 46, 231-232 on Monk’s dancing reflecting his desired rhythmic pulse for the band; for further philosophical implications centering swing see Carr 2023.

[18] Jason Moran comments in a Downbeat Blindfold Test on Carmen McRae’s lyricized arrangement of “Straight No Chaser,” entitled “Get It Straight”: “The lyric that jumped out was ‘The time is a dancer’ because that’s one of the most important things about… Monk” (Moran/Alouette 2018: 98).

[19] See also Baraka on polyrhythm as a Pan-African “acknowledgment of several…‘places’ … existing simultaneously” (Baraka 2009: 23).

[20] See Robin D.G. Kelley for an account of Monk’s beating by police in Delaware: “According to Nica…one cop started beating on his hands with a billy club, his pianist’s hands” (R.D.G. Kelley 2009: 254). See also Art Blakey on Charlie Parker, Bud Powell and Monk: “I watched… how they destroyed [Bird] and Bud and the way they’re destroying Thelonious Monk now” (A. Taylor 1979: 248).

[21] “The one” (i.e. the first beat of the measure or phrase) is the implicit temporal marker that serves as the point of departure for each rhythmic phrase and is loaded with metaphysical significance. Pianist Jon Batiste describes Monk’s “Evidence” as exemplifying a technique he calls “the rhyming of notes” (Batiste 2021).

[22] Both Brent Hayes Edwards and Jonathan Leal have written brilliantly on Monk’s composition as making palpable “fragmentary evidence” (Edwards 2001; Leal 2023). Amiri Baraka’s earlier reading flips the script by stressing an Africanist epistemology: “Evidence, Monk says… [Black] life is meant, consciously, as evidence…Everything is in it, can be used, is then, equal — reflecting the earliest economic and social form, communalism” (Baraka 1996: 21-22).

[23] See Kendrick Scott, “A Community Post: Thelonious Monk’s Evidence ” Recorded May 23 2020 at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W9MKcem0tAs. For Scott’s latest release Corridors (Blue Note, 2025), see http://www.kendrickscott.com/

[24] See citations of Ran Blake and Chick Corea in Feurzig 2011.

[25] See Eric Porter’s discussion of Locke’s ambivalence: “Locke’s optimism was tempered by a recognition that the popularity of jazz threatened the integrity of the music as a black expression”(Porter 2002: 47; Locke 2022).

[26] Crawford focuses on Langston Hughes’ Ask Your Mama, written after Newport Jazz Festival, where the speaker asks “What’s gonna happen to my music?” (Crawford 2017, 28).

[27] https://www.weareking.com/about. See “‘We Are King,’ With Its Deep R&B Strategies, is a Musicians’ Album” (Ratliff 2016).