Image 1. Picture posted to Facebook by a current advisor to the Interim Government, Mahfuj Alam

Bangladesh as a Civilizational Confluence:

The Dhaka University Students Dream a Dream

Naveeda Khan, Shrobona Shafique Dipti and Bareesh Hasan Chowdhury

Within a month of the fall of Sheikh Hasina’s regime and the establishment of the interim government in Bangladesh it became clear that far from the progressive types who the literati had hoped had led the July Uprising, it is instead students of a quixotic blend of nerdy scholarliness (one kept dropping the name of Talal Asad, the anthropologist, in their speech) and social conservatism who gave leadership to this movement. Once analysts like us got over our disappointment, we turn to trying to understand who are these students and what do they desire? It feels important to hear them out. After all, they risked much to go up against the security apparatus of the previous government and it was their initial deaths that pulled the middle- and working-class people into rising up. And their continued presence in the political scene represents a challenge to the usual elites who have monopolized politics in this country since its birth in 1971. And the students themselves appear willing to grow and change in light of criticisms of them.

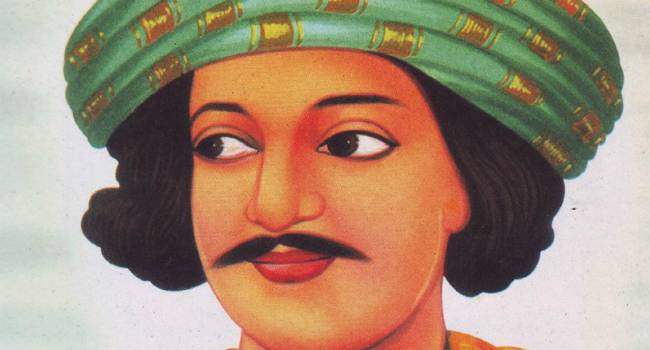

Our exposition of their thinking begins with a picture (Image 1), posted to Facebook by a current advisor to the Interim Government, Mahfuj Alam, who was previously a coordinator in the student-led 2024 Anti-Quota Movement that sparked the July Uprising in Bangladesh. A few weeks into the tenure of the interim government, Muhammad Yunus, the new head of the government, declared Alam to be the “mastermind” behind the movement. It is a claim that has since come to be disputed but that put him at the center for articulating the student position on the previous government and the political formation yet to be at the early point of the new government.

With the above picture, Alam proposes a pantheon, in the mode of a Mount Rushmore, of the historical personages that Bangladesh may rightfully claim as its spiritual founders. Alam offers them in opposition to the cult of personality that has surrounded Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who took on the mantle of founding father in 1971 and whose legatees have asserted his singular importance to the exclusion of all others. Who then are these figures?

The first on the left is A.K Fazlul Huq (d. 1962), also referred to as Sher-e Bangla (Lion of Bengal), a statesman of huge repute credited with the cultural efflorescence dubbed the Bengali Muslim Renaissance. The second, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (d. 1963), was similarly a famous statesman in East Bengal, later East Pakistan, regarded as the mentor of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and famous for proposing that an independent Bengal be created during the Partition of India in 1947. The third is Abul Hashim (d. 1974), a leftist politician who was very active in the Pakistan Movement. The fourth in the pantheon, Jogendra Nath Mondol (d. 1968), was a Dalit leader who rose to prominence within the new state of Pakistan but left for India in protest of Pakistan’s treatment of its minorities. Finally, the fifth, Maulana Bhasani (d. 1976) was a leftist Islamic politician and one of the founders of the Awami League, which was later to be led by Sheikh Mujib and Sheikh Hasina. Bhashani would split from the Awami League to form a leftist party of his own.

Together these personages bring to the fore a Muslimness that is distinct to Bengal, even perhaps specific to East Bengal, later East Pakistan and now Bangladesh. This Bengali Muslimness moves between a leftist, peasant-focused politics and a more explicitly Islamic orientation while accepting the claims of East Bengali Hindus through the inclusion of Mondal within the pantheon.[1]

Most Bangladeshis know at least a few of these figures. Yet they are not the household names that Sheikh Mujib became by means of the state-imposed historical narratives under Sheikh Hasina’s careful watch (explored under the theme of “Mujibism” in our previous instalment). The students in the interim government that now runs the country have demanded that a different history be recounted to include these figures and to spark a different imagination of Bangladesh as a political entity, beyond that of the nation-state birthed and ruled by Sheikh Mujib and his progeny. The image they favor presents Bangladesh, a coastal country with a large port, as a confluence of many civilizations, but one in which the cultural and historical contribution of Bengali Muslims is noted and in fact, is paramount.

This harkening back to “civilization” in a confluence of civilizations as a political alternative to the theater of nation-states is an emergent phenomenon. The Civilizationism Project co-hosted by Stanford University and the University of Göttingen locates its emergence within countries such as Russia, China, India and Turkey. Among the many elements of this phenomenon tracked by the project is a reanimation of imperial pasts by these countries. But this is not just a nostalgia for bygone eras. It is an expression of desire for a polycentric world as an alternative to the current economic and political world order, which exclusively centers the west. Consequently, while “civilization” as an organizing principle carries a threat of populism, even tipping into authoritarianism, this politics is outward looking and heavily mediated, emphasizing global interconnectedness.

Previously we explored how the students at Dhaka University came to be not simply discontent with the government holding Bangladesh in its authoritarian grip for fifteen years but also plagued by the question of why Bangladesh was susceptible to such capture. And their analysis came to rest on how founding figures, principles, texts and ideologies were transformed into weapons of cultural and political domination by the very party that ushered in the country’s independence from Pakistan in 1971.

In this sixth installment, we continue our study of the statements and actions of key student ideologues, such as, Mahfuj Alam, Mamun Abdullahi, and Mohammad Asaduzzaman to show how alongside crafting their diagnosis of Bangladesh’s political and economic ills, the students also explicate a civilizational state as its therapy. We ask, what was the knowledge infrastructure by which the students worked around the capture of their educational institutions by the ruling party and its student wing? How did they evade state surveillance to undertake an analysis of their condition? What are the national, regional and international lineaments of the civilizational state as articulated by the students? Why does such a framing appeal, given its ties to non-democratic, even authoritarian countries with problematic relations to its minority populations? And how is such a dream to be materialized to save Bangladesh from its fate of falling victim to fascism as understood by the students?

In what follows, we do not claim to be exhaustive. Nor do we want to give too much coherence to something that is quite piecemeal and inchoate. Rather we intend to identify a few important features of the thinking and planning that informed the 2024 July Uprising, which happened spontaneously but which in retrospect showed some cultivation of ground. Whether this dream that the students dream has legs is, of course, yet to be seen.

Self-Education in the University of Dhaka

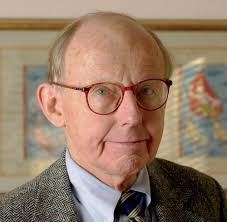

Image 2. Gurubar Adda Study Circle

In a previous installment, “How to Capture a University: Lessons from Dhaka,” we described how the AL government’s student wing, the Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL), encroached upon and took control of the university physical space from the 1990s onwards: student residences, dining halls, the sites of student government, of recreation and culture. Perhaps the only place left uncaptured were the libraries to which students retreated, particularly if they were affiliated with any of the political groups that had been driven from campus. However, a different group of students, those unaffiliated with any political parties, who sought an education unmenaced by party hacks and thugs, found ways of congregating to forge shared values. They also sporadically broke into political protest, as indicated by the many monuments to such protests across the university campus. What, then, were the practical means by which these seemingly unaffiliated students managed to come together within Dhaka University despite the clamp of the BCL upon all gathering and organizing, and what kinds of fresh thinking did they evolve?

Study circles, online journals and roaming libraries provided the occasion for discussion outside of the grip of BCL. Most notable among the discussion circles that drew upon students from the university but operated largely independent of the university was Chinta Pathchokro (“The Study Circle on Thought”), which was presided over by the poet and thinker Farhad Mazhar and had been ongoing for over a decade. This circle produced pedagogical material such as reading lists on thinkers including Aristotle, G. W. F. Hegel, Karl Marx, Carl Schmitt, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault and Talal Asad. The group sought to educate itself in critical theory as it relates to state formation, capitalism, communism, fascism, postmodernism and postcolonialism. This group advertised and organized over a Facebook site, meeting biweekly, most often at the Narigrantha Prabartona, a library managed by an organization with which Mazhar was long affiliated, with assigned leaders leading the group through lectures and close readings. The reading materials were available in both English and Bengali, with some of the participants translating and posting discussion material on Chinta’s website or publishing through its magazine, also called Chinta. This group was vital in bringing together people, including students, from vastly different political orientations who were keen for analyses of their moment and critiques of dominant narratives. Some members of the Students Against Discrimination group that organized the 2024 Anti-Quota Movement were involved with this circle from 2013 onwards.

Among longstanding journals that gave the students succor was Totto Talash, published by the Department of Bangla in Dhaka University under the editorship of Professor Muhammad Azam. The journal put Bangladesh-based scholars in conversation with well-known Indian historians and social theorists, such as Dipesh Chakrabarty and Sugato Bose. For published books the student could count on the Bangla Academy, a public research institute located within the Dhaka University campus, whose shelves held a deep stock of publications on some of the central thinkers in the history of Bangladesh, as well as well-known puthis—manuscripts from pre-partition Bengal on Islamic religious and spiritual figures, which were read out by the literate to audiences of their non-literate neighbors and which are considered an important historical source on rural Bengali Muslims. In the marketplace at large, however, the publications of the Bangla Academy had been edged out by the large-scale production of books on Sheikh Mujib, with titles such as The Making of Mujib and The Voice of Freedom.

Image 3. Rastrokolpo Library

The non-partisan students also took inspiration from the tradition of roaming libraries, which was a long-standing practice within Dhaka University. One prime example of such an effort by these students was an online library titled Rasthrokolpo Library (“Library of Imaginaries of the State,” Image 3), which occasionally laid out books on the university lawns and led discussions under the banyan trees in front of Kola Bhavan, the building for the arts at Dhaka University. The titles of some of the books pictured on their website include the autobiography of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Indian Philosophy by Sayed Abdul Hai, The Bengal Partition by Joya Chatterji, Ethnopolitics in South Asia by Altaf Parvez and so on. They suggest a more regional focus than the wider ranging readings of the Chinta Pathchokro.

The students also created circles of their own, each with one magazine or more associated with it. A study circle associated with Mahfuj Alam was Gurubar Adda (Thursday Chat). The group maintains a Facebook presence, in which we see pictures of meetings of the study circle with people gathered around tables deep in discussion, and posters of upcoming discussions (see Images 2 and 4). Among some of the topics advertised in the posters are “State and Ideology,” “Rabindranath Tagore’s Swadeshi Society,” “The Pre-History of the 1952 Language Movement” and book discussions on The Culture of Bangladesh by Abul Mansur Ahmed and Dhaka University and East Bengal Society: A Conversation between Abdur Rajjak and Sardar Fazlul Karim. These topics seem to hew even closer to Bangladesh’s history and present than the Chinta Pathchokro and the Rastrokolpo Library.

Image 4. Poster for Discussion in Gurubar Study Circle

A close look at a poster of an advertised discussion (see Image 4), similar in design to all others advertised in the website for Gurubar Adda, indicates a certain iconoclastic aesthetic that abjures figural representations[2] in favor of Bengali rendered in prosaic typeset to indicate serial number, title and place of discussion, and contact phone number, while Rastrokolpo, the sponsor, is rendered in calligraphic Bengali. The “adda” in the title of the group may indicate the strong influence of historian Dipesh Chakrabarty who has written on this form as pre-Partition Bengal’s equivalent to the public sphere. The magazine associated with this study circle was Purbopokho (“East Side”).

Image 5. Cover Page of Ronopa

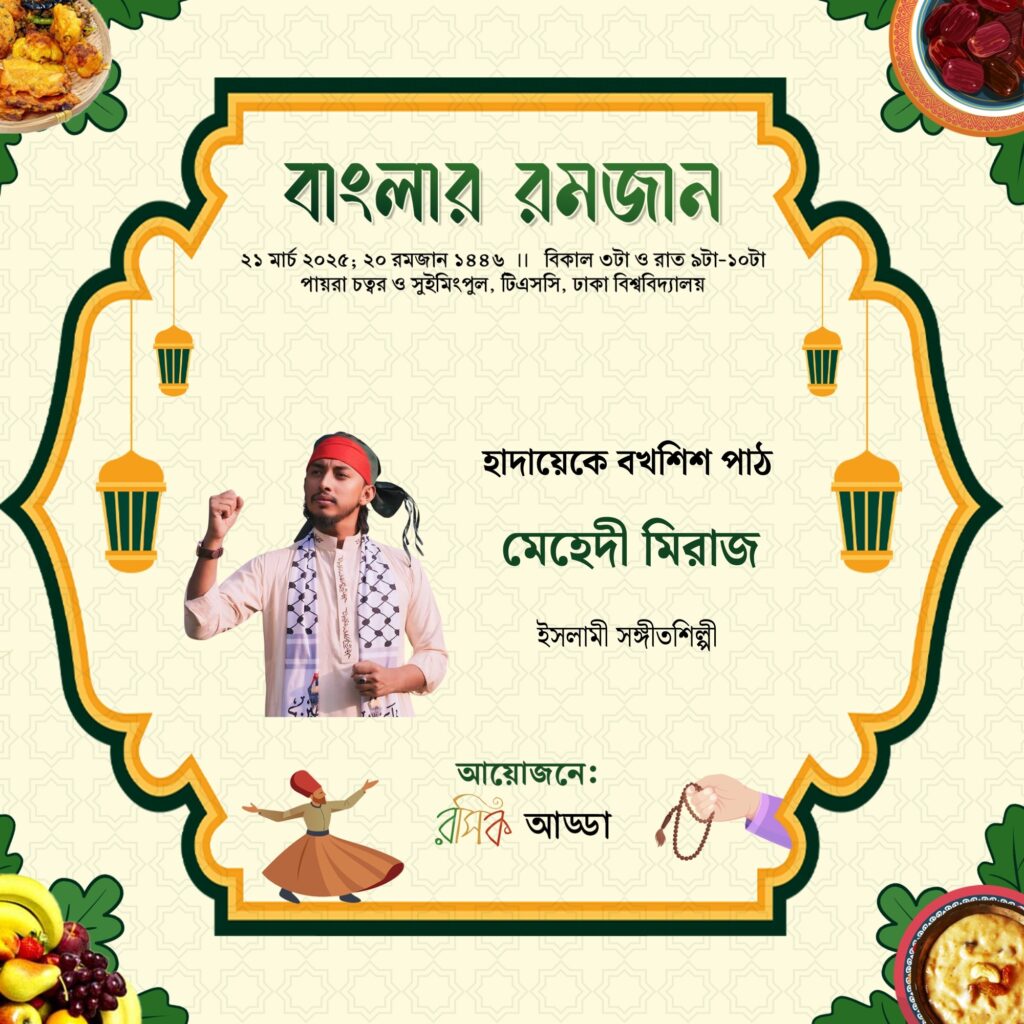

Image 6. Poster for Banglar Romjan

If Gurubar Adda and Purbopokho focused on more explicitly political and historical topics, Roshik Adda (“Humorist Adda”), linked with the magazines Ronopa (“Stilts”), Cinejog (“Connection with Cinema,” founded by Alam on 2018) and Kalondor (“Sufi Mendicant”), carved out a distinctive space for experimentation with religious, cultural and musical forms. For instance, Cinejog co-hosted events such as Banglar Romjan (“Fasting in Bengal”), which blended Islamic texts (Hadaiq-e-Bakhshish, an early 19th century text by Ahmed Raza Khan), Sufi qawwali (music), and Bengali aesthetics, along with global references, such as the keffiyeh and the whirling dervish (see Image 6). At spaces such as traditional food exhibitions, they showcased foods that had fallen out of fashion, such as the district Sylhet’s Akhnī (rice dish), Barishal’s Molida (pina colada), and Old Dhaka’s Bakarkhani (crackers), to revive regional culinary memory. Kalondor explores music across the spectrum, from the Maizbhandari Sufi lineage to Pink Floyd, mapping a cultural terrain that is both rooted in the region and expansive.

What seems to be emergent in these study circles and their associated magazines is a mix of the political and cultural, loosely held together by an interest in articulating a Bangladeshi Muslimness that incorporates references to the wider region of Bengal as a delta and Bangladesh as laying a specific claim upon this particular regional identity. In the editorial in the first issue of the magazine Ronopa (Image 5), the editors declare themselves uncertain as to what to call their publication–a magazine of art and literature or simply a “small mag”? Who, they wonder is even drawn to such a thing in the digital era? Nonetheless, the editors feel that such a venture is worthwhile, a possible resource for people when they feel themselves hollowed out by their addiction to the digital and the visual and require sustenance. Ronopa promises to give people a zoomed-out perspective on their lives, as well as some ideas for how to overcome the many divisions among them. These words implicitly criticize the Hasina state for inciting division—a criticism that is later amplified by students during the Anti-Quota Movement. The editors of Ronopa ask its readership to welcome the magazine as their new, encompassing and nourishing environment, as if in anticipation of a new Bangladesh.

National and Regional Alter-histories

Image 7. Ali Miyan

Image 8. Dara Shikoh

Image 9. Raja Ram Mohan Roy

Image 10. Kazi Nazrul Islam

The civilizational state envisioned by the students involved with the July Uprising is spoken of along two axes, regional and national, and international. The regional and national axis provides the historical content for the vision of Bangladesh as a civilizational confluence while the international provides examples on offer by different nation states leaning into the civilizational discourse. In this section we discuss the regional and national dimension of the students’ vision before moving to the international in the next.

The students’ view of Bangladesh as a regional-national entity moves between two temporalities. Along one, Bangladesh is seen as a young country, born in 1971, a mere 54 years ago, a sovereign nation among other nations within South Asia. Along the other, it is seen as a recent name for a historical node of the many movements on land and water across the ancient landmass of the Indian subcontinent. Leading up to the July Uprising, the first temporality prevailed. But in contrast to the usual historical narrative of liberation and progressive development, the students deploy the language of trauma to indicate state violence against its own people, specifically students. This history is not particularly deep, starting in the 1990s and extending to the present, and is marked by fateful years of encounters with the state and the names of martyred students (see “How to Capture a University”). The students’ insistence on recounting this history show them to be positioned as memory keepers in the face of what they view as a generalized amnesia among the polity, specifically Bangladeshi intellectuals and political leadership.

While, as we saw in the earlier section, the students read widely and deeply, they are drawn to specific texts and storylines. One among those texts is K.N. Chaudhuri’s Trade and Civilization in the Indian Ocean, which describes the Bay of Bengal as a hub of civilizational confluence, with a focus on the Arakan port. In this history of the long durée of Bangladesh, tales of Hindu, Muslim and Buddhist communities living alongside one another dominate. And in keeping with their commitment to recovering the deep past, the students recall historical figures such as Atish Dipanker Shrijnan, the Buddhist scholar born in Bengal in 923 CE, whose travels and teachings brought many communities into interrelation.

Statements by Mahfuj Alam, who once quipped that “Sultan Zauq Nadvi received the taste (zauq) of knowledge from Ali Miyan,” indicate a clear appreciation of the Islamic intellectual tradition of the Nadwat ul-Ulama of India. They show an inclination to complicate the secularism historically attributed to Bangladeshi Muslims and to unveil the genealogical, intellectual and spiritual links between Bangladesh’s ulama with important religious personae in the region.

There is also a tendency in the opposite direction, which is to reclaim secularism from the maws of Mujibism. This reclaimed secularism is attributed to an older series of historical figures, notably Dara Shikoh, the Mughal emperor; Raja Ram Mohan Roy, the head of the Brahmo Samaj, a socio-religious reform movement in colonial India; and Kazi Nazrul Islam, the Bengali Bangladeshi poet reputed for his revolutionary zeal and pan-religious expressivity, among others. We may see this trio as counterposed to Islamist and Hindu extremes.

The students advocate the learning of languages, such as Pali, Persian, Arabic and Urdu to revive past lines of connection between Bangladesh and the wider region. Several geographic locations in the region are marked as particularly sacred and historically important, notably Sylhet, seen as the gateway to the Himalayas, and Chittagong, the site of a major port of the Indian Ocean.

Even as the students emphasize this deep historical past by listing notable texts, figures, languages and sites, their presentation rarely proceed beyond the generic. Even before the students rebelled, this alternative vision of the past had been present within the Dhaka University campus for many years, including Atish Dipanker Shrijnan, the Bengali Buddhist scholar in 923 CE mentioned above; Baro Bhuiyan, the group of chieftains who held sway in 13th Century Bengal and who for a while successfully spurned foreign intrusion into the area; and Alaol, the 17th Century Bengali Muslim poet who wrote epic poems which brought him into the pantheon of famous poets in the region. This rival vision of the past included the puthi manuscript tradition, mentioned above, by which the Bengali Muslim masses of the countryside were educated into the Islamic tradition, as well as the pala gaan, the musical form which recounted important historical events within Islamic history and emerged as a space of contestation and connection between Muslims and Hindus. The somewhat superficial character of this historical list—selectively and at times even pastiched, scarcely attentive to women and minorities—raises questions as to whether the students are proposing a vision for Bangladesh which is indeed new, concrete and actionable or whether they are simply recycling comfortable alter-histories ready at hand for them. Nor is it clear by what criteria one is to go looking in the history books for details of significance for this vision.

International Coordinates of the Civilizational State

Image 11. Zhang Weiwei

Image 12. Aleksandr Dugin

Image 13. Samuel Huntington Image 14. Recip Tayyip Erdogan

In addition to looking at regional and national histories and traditions for the civilizational state, the students looked for international alternatives. In study circles, such as those sketched above, the focus often fell on the concept of the state and civilization (rashtro o shobbota) in countries other than the U.S. Here are some countries which may or may not have appealed to the students, but which provide exemplification of the civilizational state.

China is put forward as an example of a country with a history of state formation different from the Western model. The students explored how Confucian principles operated within the Chinese context to unify diverse ethnic groups under a single civilizational identity. Among those studied was the scholar Zhang Weiwei, who advocates China’s unique governance system as a model for global adoption.

Aleksandr Dugin, the Russian nationalist thinker who has made right-wing thinking almost hip and has a large following among young men the world, is also read in the Bangladesh context. His advocacy for a multipolar world order is used by the students to help build on Weiwei’s critique of American hegemony. Samuel Huntington’s famous clash of civilizations thesis, with its characterization of seven world civilizations, is similarly studied from the perspective of imagining such multipolarity.

India’s BJP-led government is examined to understand how it grounded its territorial and cultural expansion within a civilizational rubric. Among other countries that also come up for examination and possible inspiration are Russia and Turkey. The students are particularly fond of Recip Tayyip Erdoğan, the President of Turkey. Mahfuj Alam gushes over his meeting with Erdogan when they are introduced by Yunus, the head of the Interim Government of Bangladesh, at the Developing-8 (D8) Summit in Egypt, appropriately themed “Investing in Youth and Supporting SMEs.”

One may speculate that the civilizational state recommends itself to the students because the nation state framework feels exhausted, while liberal capitalist democracy seems evacuated of any values by which to hold people together. Certainly, the act of mythologizing so as to put forward new values as ancient ones is central to the discourses of the countries mentioned above. For instance, China speaks of 5000 years of its history as though it is contiguous to the present, calling upon this past in support of nationalist values such as those of prosperity, civility and harmony.

Something similar may be seen to be at work in the students’ insistence on returning to the Bengal Sultanate. Bringing together all of Bengal, this sultanate dominated the region from the 14th to the 16th centuries. It ruled by land and by sea. It fostered a series of small towns along the Bay of Bengal that served as important points of relay between land and sea, and the sites of a vast circulation of peoples and goods. The students seek to make this past the one to emulate rather than the intervening centuries. Perhaps they see in it the values of connectivity and cosmopolitanism that marked this era. Or perhaps it marks a moment of consolidated power that attracts them after the profound disenfranchisement they felt under Awami League and in the hands of its student members.

An important part of their current discourse is to ask how Bangladesh may be newly imagined within the world system and not only through marginality. Of course, this too was the discourse of the previous regime, which claimed to have developed Bangladesh to the point of becoming a middle-income country from being a low income one. However, this narrative has been shown to be overblown, and one that the students reject entirely and not only because of the growing inequality and democratic backsliding of the last few decades. They see the previous government as having made Bangladesh into a vassal state of India. Thus, the past of Bengal Sultanate may also attract in providing a picture of the last time Bengal experienced perfect autonomy, thereby linking it to present-day Bangladesh newly freed of authoritarianism and vassalage.

This revival of interest in the Bengal Sultanate will likely animate many conversations within Bangladesh as evidenced by the large international conference hosted by the Dacca Institute of Research and Analytics (DIARA), a think tank associated with some of the students, over August 2025, and that takes its name from the landmass presided over by the Bengal Sultanate. The Bengal Delta Conference, advertised here, is introduced by a video of high production value titled “The Power of Hope” which is worthy of analysis as an act of mythmaking. It puts the 2024 July Uprising in line with Bengal as a geological formation arising out of the Himalayas, and a historical site, notably from the 17th century onwards.

At the same time as they take up the civilizational language with alacrity, the students also highlight the problems plaguing those countries claiming to be civilizational states. For instance, they note that there are large swathes of the population within the countries who are not merely marginalized but actively discriminated against, such as the Uyghurs in the case of China, Muslims in the case of India, and Ukrainians in the case of Russia. Instead, they propose recasting the civilization state, to separate it from its hubristic, imperial past, and to link it instead to a wider and older geography of movements before the advent of national borders, with diverse communities held together by an ethic of hospitality. It may be speculated that Dugin’s advocacy of Euroasianism as an identity that was neither Europe nor Asia may have proven attractive because of its tendency to emphasize geography as the grounds for theorizing new political identities. This seems in line with the students’ emphasis on Bangladesh — or rather Bengal — as a geological formation, a deltaic basin and the site of civilizational confluences.

In the students’ reframing, the reanimation of the civilizational state ought not to trigger the exclusions and purifications undertaken by these other states drawing on their imperial heritage or desires for national homogeneity. The civilizational state can instead be brought about through what the students consider a cultural transformation. It is to understand the theory of change underlying this vision of the civilizational state that we next turn to Mahfuj Alam’s many speeches and writings.

Mahfuj Alam’s Theory of Change

In his first speech (August 11, 2024) to the public shortly after the July Uprising, Mahfuj Alam declares as the call of the moment:

Now you have to redefine each community (borgo). If you have to do politics in a new way, you have to redefine each community to progress (agano)….What will be the “reconciliation process” for this “nation?” How will people of this country be one collective (jot)? The people of this country, these 20-25 days, one thought (dharona) in one place came together into one opinion (moth). And there was no division. How will you “reenact” that lack of division? We raised this question, and for this reason we used two terms, a society of compassion and accountability (dai o dorod er shomaj).

These statements, restated in many ways, echoed in many different sites, including Facebook, and mainstream newspaper and television outlets, capture Alam’s thinking on what he considers the main accomplishment of the July Uprising, which is to provide the template for Bangladesh transforming into a civilizational state. He points out that in the middle of the movement, people were united, of one opinion, with no divisions among them. While we know that this movement was the product of organizing by students across the country, with its scaling up to a mass movement largely providential, we take his remarking on this unity to be drawing our attention to both a momentary reality and a horizon of aspiration. And, as we know from his diagnosis of the problems besetting Bangladesh in the shape of Mujibism, for this reality of a division-free people to rematerialize, the moment calls for clarity on what happened in 1971 during the war for liberation. It also calls for clarity on the years that followed during which Awami League set up a nation state. And it calls forth moral resolution to face this violent and selectively rendered past with honesty, to seek out truth and justice for all, and to do so from the ground up rather than the top down.

It is unclear how this task of historical reckoning is to be undertaken. Rather than offer any concrete methods, Alam offers compassion and accountability as the orientation by which it is to be undertaken. But the yoking of the two is also ambiguous, as accountability recalls disinterested procedure whereas compassionateness is a sentiment that could have no place within such a procedure (although of course it may be seen as emphasizing the pastoral aspects of government).

Alam’s thoughts on what comprises the civilization state is rent by contradictions. In some of his accounts, as in the August speech, Bangladesh is already a civilizational state by dint of its geography:

Why should the state called Bangladesh keep standing on its own? This is if you consider the “Bengal Basin,” we are sitting on the “Bengal Basin,” the “basin” is our land, our country is a “basin land.” A “civilizational confluence” has occurred here, all these different civilizations have come together.

But in other moments, he calls for a “civilizational transformation” yet to come:

May a society of mutual responsibility and compassion be established in the Bengal delta and Bay of Bengal region.

Interestingly, even in this newly recollected older Bangladesh as basin, the orientation is not quite right, being vectored towards the northwest, the Indo-Gangetic, North-Indian milieu, along what is called the Hindi-Hindu-Hindustan axis. Bangladesh is to be newly vectored to the Bay of Bengal and the lower southeastern region to generate new circuits of interrelatedness, specifically through Chittagong-Madras-Colombo-Aceh rather than routed through Delhi-Lucknow-Varanasi as before.

Despite his commitment to change from the grounds up, Alam sees constitutional reform as the most expeditious way to bring about this civilizational state. He differentiates between the 1971 Constitution, which he refers to as being ideology based, and the one that he proposes which will be value-based, specifically those of democracy, equality, human dignity, and justice. He feels that divisive issues, presumably issues on which there is not yet universal or near universal agreement, should be excluded from the constitution to prevent it from being overly proscriptive, thereby preventing further division and conflict in society.

While noting the achievements of the July Uprising and sketching out, albeit in very schematic ways, the means to secure these accomplishments, by grounding them in a cultural transformation of Bangladesh from a rapacious nation state to a hospitable civilizational state, Alam remains alert to the forces that threaten his ambitions. As he says in his August speech:

We know that after revolution comes the counter-revolution. I wrote this even before the revolution that they will come through a counter-revolution but it is not that we should be panicked, who will take us away, who will kill us. The thing is not like this. The thing is, you the people, what I said, this moment that was created in those 20-25 days, this moment, you must keep reenacting.

Citing theater work that he has done in the past in which the method is one of enactment and re-enactment:

We might need another mass uprising. I will repeat myself again and again. We must think about reenactment.

In some ways we may hear this as a threat that if Bangladesh does not change to the satisfaction of the students and their supporters, then they will enact and reenact the uprising as needed. However, we may also read his words in another way, which is that Bangladesh as a civilizational state should not commit to one form once and for all but build self-correction into its make up. In a manner of speaking, we may think of Bangladesh as fashioned on the structure of a study circle, constantly reading, discussing, assimilating the best its history and the world has to offer, and revising as needed.

Concluding Discussion

Image 15. The Insignia of the National Citizen Party

In conclusion, we may ask what have the students been able to achieve by way of laying the foundations for this much vaunted civilizational state of Bangladesh in the year since the uprising? Let us reprise some of the main events since August 5, 2024. The demand for a new state by the students led the interim government of Yunus to create eleven commissions to reform different parts of government, including the Constitution, police, women’s affairs, etc., yet inexplicably not one on education. The commission to reform the Constitution has been the one that has acquired the greatest symbolic significance in terms of restructuring the existing template of the state. It has called for a new upper body of government to be created to oversee the activities of the Parliament, while the main opposition party (Bangladesh National Party or BNP) maintains that such changes can only be brought about by an elected government. Following the completion of the work of the eleven commissions, the National Consensus Commission (NCC) was created to forge consensus among the various political parties over a whole slew of fundamental reforms. It drafted a July Charter as a kind of Magna Carta to orient such reforms. Even though the NCC was putatively to initiate reforms of the state, it is not clear whether they retain the authority to do so. After all, the students themselves have gone on to create a political party, National Citizen Party (NCP), independent of the interim government. And the NCP has joined with other political parties in raising reservations over this charter. We might say that the grand ideological vision that the students proposed through the civilizational state appears to have given way to the pragmatism and jockeying for power in advance of elections tentatively scheduled for February 2026 that characterizes politics in Bangladesh. Or we might consider that that vision served its purpose of inspiring a movement, widely seating a desire for state and societal reform and, perhaps in time, may foster accountability and compassion within society (dai o dorod er shomaj) as the students hope. For now, we can say that it has boosted a new generation of leaders from among the students.

Bareesh Hasan Chowdhury is a campaigner working for the Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association on climate, policy, renewable energy and human rights.

Shrobona Shafique Dipti, a graduate of the University of Dhaka, is an urban anthropologist and lecturer at the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh with an interest in environmental humanities and multi-species entanglements.

Naveeda Khan is professor of anthropology at Johns Hopkins University. She has worked on religious violence and everyday life in urban Pakistan. Her more recent work is on riverine lives in Bangladesh and UN-led global climate negotiations. Her field dispatches from Dhaka in the middle of the July Uprising may be found here.

[1] It is important to note that while Mondol may be considered a Hindu, it is more appropriate to indicate that he is a Dalit, that is someone in the lower castes, outside of the main castes making up Hindus.

[2] A speculation for this stylistic choice may be to appeal to a wider range of students, including those more pious who disapprove of figuration.