This text is part of a b2o Review dossier on Charles Bernstein’s The Kinds of Poetry I Want.

Constellation, Frame, and Provisionality in Charles Bernstein’s Kinds of Poetry

Elin Käck

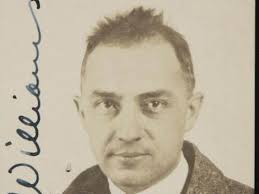

“What about all this writing?” This question, which sounds like it may have come straight from the mouth of the executer of some literary estate who has just found an entire room full of boxes of unsorted texts and wonders what to make of them, was uttered by William Carlos Williams in the poem labeled IX in Spring and All (1923). It arguably constitutes an important meta-poetic statement (1986: 200): for it directs our attention to the uncertain—or provisional—status of the work presented in the volume itself: daring and, for lack of a better word, experimental, breaking with all sorts of expectations. It is as though the work itself is being negotiated by the poet as we go along, moving through the disorienting sequences of his poetry.

Perhaps because I happen to be a Williams scholar and Bernstein references Williams in his new book (and elsewhere), this question—“What about all this writing?”—lingers with me throughout the volume of Bernstein’s genre-defying The Kinds of Poetry I Want: Essays and Comedies (2024). The book’s overt genre labels do not entirely account for everything that goes on between its covers. When Williams asked the question in his own genre-defying volume interspersing poetry with prose sections—a book that we might now view as an early prototype for the merging of poetry, theory and criticism at which Bernstein excels—he had no way of knowing which answers future readers would propose to his question.[1] He probably even wondered in earnest what his contemporaries would make of all that particular writing—the very kind found in Spring and All—and suspected that most of them would not appreciate it. In relation to Bernstein’s work, published almost exactly a century later, I understand the question very differently, with an emphasis on the “all” rather than the “this.” The question is not so much what to make of this kind of writing—although some people still seem perplexed at the difficult poems with which Bernstein attacks his reader, deeming him “incomprehensible, incoherent, and hypertheoretical,” as Marjorie Perloff once summarized it (2021b: 167). Rather, it concerns how to deal with the sheer mass of it. Even more so, it is a question of how to calibrate any statement about Bernstein’s work or his poetics against the many essays he himself has written on poetry and poetics, not to mention all the other forms of commentary in which he has engaged, from speeches to interviews, in various formats. Here he joins both Stein and Williams among the modernists in having created an oeuvre where it is entirely possible to read Bernstein through Bernstein, just like we can read Stein through Stein, or Williams through Williams. While thrilling and often gratifying, such a method rarely offers a final, conclusive key to their work, but instead tends to generate more questions and lead to further labyrinthine routes of reading and rereading. Yet, this is precisely what a book like The Kinds of Poetry I Want invites its readers to do, given that its title suggests the presentation of a poetics, however plural. With its many references to the author’s other essays and works, it constantly breaks its own bounds and sends its reader (this reader, at any rate) on labyrinthine routes through decades of writings. The “all” is a cumulative aggregate.

If Williams’s “all” is an apt starting point for discussing Bernstein’s work, it might be because he himself hints at a fascination with this capaciousness à la Williams in the essay “Free Thinking: Spring and All versus The Waste Land at 100.” Bernstein delivered the essay with characteristic verve at the 2023 MLA Convention in San Francisco, on a panel which I convened for the William Carlos Williams Society to celebrate a century of Spring and All and the fortieth anniversary of Bernstein’s own “The Academy in Peril: William Carlos Williams Meets the MLA” speech, once presented at the very same conference.[2] At one point in the essay, in his discussion of Spring and All, Bernstein makes it clear that it is indeed the “all” that entices: “We are all strangers in the wilderness of language. Spring and All imagines that. And it’s not the ‘spring’ but the ‘all’” (2024a: 161). In the 1983 MLA speech, this all which Bernstein so strongly advocated for included what had previously been termed mere “rhetoric,” meaning the prose sections interspersing the short poems that would come to be canonized (2001: 246). Today, most people would agree that Spring and All really needs “all” in order to be fully understood as an avant-garde masterpiece. All the writing of which Williams asks his readers in poem IX of Spring and All is now deemed indispensable, integral to the work. What was once a source of uncertainty and seen as mere excess, out of place and muddling the sight of the actual items of poetic value, is now perhaps even one main reason for the work’s continued canonization. To speak with Bernstein’s own abbreviation system in the essay, Williams seems awfully close to having become part of OVC, official verse culture, first on the basis only of the lyric poems, and now for the work as a whole (but maybe this is calling it too soon; after all, I was asked as late as 2010—in disparaging terms, no less—why I would want to spend my time writing about the prose of Spring and All).

If Williams daringly expanded the poetry volume and reimagined its scope so as to accommodate criticism, essays, cantankerousness, speech, and philosophical ideas, then it is safe to say that Bernstein’s work has taken this capaciousness and sense of accommodation even further, expanding not only the frame (a crucial word to which I will return later) of the poetry volume, but of scholarly writing as well as of writing and/as performance. Indeed, it is impossible to read some of the pieces in his new book without simultaneously hearing them performed in one’s mind, in the loud and powerfully engaging way Bernstein has of delivering his speeches. This innate aurality comes as no surprise, given his profound interest in sound, theorized as a dichotomy between “sound and unsound” writing (2024a: 350).

In “Sounding the Word” in Pitch of Poetry, Bernstein has his text self-consciously point to its use of an italicized that as “a script code to tell you that if you read this out loud you should give an extra emphasis to that, pausing slightly before it” and then suggests to the reader just how the essay would sound in a parenthetical paragraph: “For the real experience of this script, play it on your computer’s voice reader and set ‘Ralph’ for a rate of 35, pitch of 36, intonation of 82” (2016: 30, 32). But there is really no need for overt directions, whether real or made in jest; anyone who has ever heard him read is able to imagine just how a line or sentence might sound when delivered in his voice. At the 2016 MLA Convention in Austin, the panel next door even came in to ask him to pipe down, as they were having trouble hearing their own presentations with the noise from our crowded room emanating through the walls when Bernstein read “The Pitch of Poetry,” presumably a pitch or two too high, in the panel Reconceptualizing the Lyric. The conference frame encroached on the performance frame, to the amusement of everyone in the audience and, if my memory serves, to Bernstein himself, who took it in his stride, but who did not significantly lower his voice (I doubt he could even if he tried).

While this anecdote might suggest that the MLA convention is not conducive to the kinds of conference presentations Bernstein wants, not to mention the kinds of poetry, such a conclusion would be too rash. In “95 Theses,” Bernstein explains his view on the MLA as a context for his work: “Contrary to what some members feel, I have always found the MLA convention, with its knowledgeable and often enthusiastic listeners, an ideal place to present my work” (2024a: 15). In the recent essay “Which Side Are You On?” he spells out even more clearly how the conventions that, in his terms, “often seemed like a giant sensory deprivation tank” were essential contexts: “The positive reception of my Ciceronian style, not to say stand-up, was greatly enhanced by this environment” (2024b: 93). What’s the use of a frame if you can’t break it? Or, rather, how break a frame if there is none? With these considerations in mind, of course the MLA convention is ideal.

Characteristically, for Bernstein, writing always generates more writing (again, all this writing); texts bring about texts, poems bring about poems, bring about essays, bring about speeches, bring about criticism, bring about poetry as criticism, bring about email conversations and interviews and letters that then later become new essays or even poems, which in turn is only a fraction of an enormous output of everything from email lists to radio programs to cult online repositories such the Electronic Poetry Center and PennSound, all of which can and do generate more writing. There is a capaciousness that seems to know no bounds and thrives in excess.[3]

There is also an “endless quest for material,” as he admits in an interview with Perloff, elaborating on the practice of collecting spoken language from different contexts and in different registers, using it for his poems (Bernstein 2011: 248). This endless quest seems to me to pertain just as much to the repurposing, or recontextualization, that forms such a vital part of Bernstein’s method: culling material from the surrounding world and wealth of language in the everyday (much like Williams did in his poems of the everyday and in works like The Great American Novel with its vast collection of competing registers) is really only the first step, just like the poem is only the second.

There are also third, fourth, maybe even fifth steps, where materials get transposed, recontextualized, rethought, or reframed—where the quest for material turns toward the already-collected materials to think anew about their potentialities. Nothing is really ever final, as demonstrated most aptly by the revised obituary for David Antin, included in its original form with the author’s hand-written notations in The Kinds of Poetry I Want, with the explanation of how, at a memorial event for Antin, “I presented a commentary on my obituary, adding to it and contradicting it, based on notes I made during the first part of the program” (2024a: 338). The movement of material, as it were, is at least as important as its careful emplacement on the page of the poem, where it resides permanently but also, as it turns out, sometimes provisionally. In “Dichtung Yammer,” Bernstein elaborates on one particular iteration of this method, the frequency one, where the most common words of chosen previous works are sampled to create new ones: “I’m mining (and minding) the earlier works to create alternate versions via vectoral data slices,” a method that he notes recalls the “distant reading” of digital humanities (2024a: 266). The new context for the already-written is in itself generative, for “the same line is not the same depending on who said it or what the context is,” as Bernstein explains in Pitch of Poetry (2016: 199).

It is telling that the anecdote of the publication of All the Whiskey in Heaven contains an observation on the process of selection to the effect of sculpting “from a large mass of writing” (2024a: 118). Bernstein elaborates on this in the 2010 interview “Chicago Weekly” with Daniel Benjamin, collected in Pitch of Poetry, where he describes this collection of selected poems as one in which

. . . the poems, taken from thirty years of work, are repurposed to be part of this new serial work, with the book as organizing principle. For the selected, I wanted to suture together disparate, even opposing, forms, in order to create a mobius rhythm out of the movement among the discrepant parts; the meaning is as much in the space in between as in the poems themselves. Each poem does have its autonomy, but the book as a whole works more as an installation than a collection. (2016: 243)

Installation seems an apt term also for the most recent book with its bringing together of various forms not with the aim of creating a sense of perfect balance or unity, but with movement at the center of the project: movement in both spatial and temporal terms. We are journeying through decades of conversations and ideas, but always somehow in tune with the most pressing questions of our current moment, just like texts moved from a previous context generate new ideas and spark new connections in new arrangements.

The pieces collected in this book at times strongly imply more writing to come, as in “95 Theses,” where the final thirty-one have been left blank, to be filled in by the reader, but, one thinks, why not, at some later point, by the author himself, picking up a thread begun years earlier. Blanks and gaps open up for new takes and essays expanding on or developing something already-written further. This ties in with Bernstein’s own claim of his work’s provisionality, in the essay/conversation “Too Philosophical for a Poet: A Conversation with Andrew David King,” where he states that “I see my books as provisional exhibitions” where “other constellations are implicit” (2024a: 119). Here we see an example of Bernstein’s preference for the term constellation, which he elaborates on in “Dichtung Yammer”: “Books inside books create more possibilities, clusters, webs, matrices—echoes. More strings attached” (2024a: 271). Uttered as a comment on the organization of Topsy-Turvy (2021), this also provides a fruitful guide to other works, even if the units might not be “books,” but something else. While provisionality as such might be construed as a charge against his work—as a sign that a Language Poem ends randomly, by chance, rather than design—I take the provisional exhibitions to be highly and most consciously curated at each stage, in each iteration.[4] Provisionality does not here mean impressionism or incompleteness, but instead an affordance for movement and reconfigurations that produce new meanings and potentialities.

Constellation and frame, along with provisionality, emerge as central terms for Bernstein’s practice: terms from the worlds of avant-garde art and pragmatics respectively. Taken together, they seem particularly able to accommodate the vast span—volume, spread—of his work in different genres. They provide a language for discussing essays, speeches and comedies just as they do for approaching long, slender poems replete with mid-word line breaks, centered on the page, like “Thank You for Saying You’re Welcome” and “Truly Unexceptional,” in Near/Miss, the latter so slim that it almost “dis-/sol-/ves” as its words are stretched out, like a Giacometti sculpture, across the two pages it spans (2018: 56). They are also helpful in approaching one-sentence poems like “A Unified Theory of Poetry” in Topsy-Turvy, which is briefer than its title and simply reads “I don’t think so” (2021: 75). They allow for a description of the poem on the page just as they accommodate the movement inherent in repurposing or reframing when items from one poem or essay are morphed into something else, be it a poem or a work in another genre, or are remediated through performance.

It is not surprising that these terms largely come from and are employed outside of the realm of literary theory or literary studies. Bernstein’s poetics is founded on the interactions between fields, unceremonious in the face of the disciplinary. I spend my everyday academic life in the company of linguists working within interaction, multimodality, and Conversation Analysis (CA), so when I came across Erving Goffman’s name in Bernstein’s description of framing in “Dichtung Yammer,” I realized that we have mutual friends. Goffman is a household name in my department for his importance to pragmatics (from this perspective, it figures that Bernstein would term his poetics largely “pragmatic” in “The Humanities at Work” in Pitch of Poetry [2016: 225]). Goffman’s Interaction Rituals (1967) was one of the readings for the obligatory linguistics course in my PhD training some fifteen years ago. Maybe this type of work, more than anything else, is what best prepares someone for reading a poet like Bernstein?

At the beginning of Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience (1974), Goffman takes the reader for quite a ride. This occurs already in the book’s preface, which constantly draws attention to itself as a preface that is commenting on its status as a preface, and which also posits a number of ‘what ifs’ for the reader to consider. While a preface is known to be a place in which to adjust reader expectations and speak candidly about a book’s limitations, often apologizing for what is to come and thus actively framing the work for the reader, what would happen if a writer instead did something else, like comment on the preface or state who didn’t help with the book’s making, rather than who did? What if, Goffman asks, “I had said: ‘Richard C. Jeffrey, on the other hand, did not help’” (1986: 18).[5] As he concludes the preface and this series of examples, he states: “That is what frame analysis is about” (20).

Characteristically, The Kinds of Poetry I Want offers no guiding preface by the author to manage reader expectations, but its wonderful foreword by Paul Auster (also repurposed, from a 1990 reading as well as from the 1996 Why Write?) provides the reader with important clues, calling Bernstein a “trouble-maker” as well as “unpredictable” (2024a: ix). Playing with the frame, altering expectations, and shifting cues to move the reader from one realm to another, one genre to another, one set of ideas to another—all of these are prevalent elements in Bernstein’s constantly evolving repertoire. He states it himself in the essay “Offbeat”: “Poems, the kind of poetry I want, use reframing as a process” (2024a: 29). Reframing is also something that the reader actively does: “Reframing is the reader’s response, at least if the reader wants to take the ride offered. . .” (2024a: 29).

The frame as such is almost imbued with magic, or, as Bernstein writes in the poem “Nowhere Is Just Around the Corner” in Near/Miss: “A frame / is like a rabbit pulled from a / hat in Dallas, 1948” (2018: 23). Bernstein’s shifting or provisional frames are deeply connected to surprising leaps of language—to catachresis and the unexpected pairings of words—let’s call them slant pairings, to echo the concept of slant rhymes, known for their defamiliarizing and vaguely troubling effects. It is no coincidence that the word “ostranenie” occurs in the poem “Catachresis My Love” (2018: 33). When “words pop up in surprising slots,” as Perloff has termed this practice (2021b: 168), it is also a matter of framing: the slots are frames, emplaced within other frames, but inside the frame we find something completely different from what the frame (and here it may be a syntactical frame as well as a semantic one) promises. While the term slot might seem to signal mostly something quite stationary and fixed, conditioned by the syntagmatic axis, there is a strong sense of movement unleashed by this element of surprise. Thus, we manage to maintain in two or more places at once; we are on our way somewhere (what the statement ought to say) only to discover upon arrival that we were going somewhere else all along (what Bernstein says). As he explains in “Dichtung Yammer,” “Substitutions are the tissue of my text, whooping and Whorfing and generally making merry, at least for a time, before the mood turns black” (2024a: 262). Calcified sayings, connotations, and rote language use all ensure that we recognize the expected end point, so that we are sure to realize that we have in fact ended up somewhere else. Perloff has a handy description of this practice too, as Bernstein’s proclivity for “creating whole poems out of faux-aphorisms” (2021b: 169).

Embedded in the exploration of the versatility and at the same time boundedness of language, we actually encounter another link to Williams, who would return to the idea of language as enslaved and in dire need of being set free in a fashion that only the poem could bring about. To his mind, only Gertrude Stein had ever managed to effect anything coming close to such a liberation. “It’s the words, the words we need to get back to, words washed clean. Until we get the power of thought back through a new minting of the words we are actually sunk,” Williams writes in the essay “A 1 Pound Stein,” (1969: 163). Stein, according to Williams, “has gone systematically to work smashing every connotation that words have ever had” (163). In a relationship between language and capitalism, where the latter has enslaved the former, words need new minting: they need to be entextualized. I do not propose that Bernstein’s goal is some kind of end of referentiality or final loosening of language from connotations, and even if it might be possible to find traces of such a stance by searching through every single recorded statement he has ever made, a statement to the contrary comes to mind, where in fact he claims that we rely on referentiality: “You really can’t strip yourself of the associative qualities that words have” (2024a: 24). Mikhail Bakhtin would have agreed. As he pointed out in “Discourse in the Novel,” an essay that I have always found useful rather for the discussion of poetry, “Each word tastes of the context and contexts in which it has lived its socially charged life; all words and forms are populated by intentions” (1981: 293).

Despite this inherent stickiness of language, there is something in the movement between frames and registers that allows for that “power of thought” that Williams was after and hoped to reclaim in his essay on Stein. In “Poetics and Performance as Critical Perspectives on Language and Social Life,” Richard Bauman and Charles L. Briggs propose the idea that “performance potentiates decontextualization” (1990: 73). Performance has the potential to make discourse “extractable,” specifically through “entextualization,” which loosens it from the previous contexts in which words have occurred (73). While Bernstein relies on the echoes of his echopoetry to carry over into the new context, so that the reader’s references are activated, it would not do to have the old contexts move in too heavily on the new work. The trick is to achieve a state in which they are both equally activated at the same time. As Bernstein notes in “Thelonious Monk and the Performance of Poetry,” “all reading is performative / & a reader has in some ways to supply the performative / element when reading—” (1999: 19).

Constellation, the other term suggested here as a fruitful way of getting at what happens in Bernstein’s work, is linked to frame and framing, since what is framed can appear in different constellations or frames can cut through the material at various points, including or excluding something. Provisionality, too, is related to this practice, as it allows for a reframing, or a rethinking of constellations, which can become reconstellated, if there is such a word. “Don’t revise. Rethink,” as Bernstein writes in “Catachresis My Love” (2018: 35). This brings us back to Spring and All and the prose that Bernstein defended at a time when others dismissed it as rhetoric, a term used to communicate dislike, rendering this prose especially suspicious, as the opposite of the poem, or at least of the venerated lyric poem. In “95 Theses” in The Kinds of Poetry I Want, Bernstein directs us to what I have always found the most compelling feature of his work: the dialogue between poetry and criticism. The twentieth thesis states: “Criticism, scholarship, and poetry are all fonts of rhetoric. The aversion of rhetoric is an unkind kind of rhetoric” (2024a: 16). A statement like this explains why Bernstein found it important to criticize those who, as he viewed it, undervalued what they saw as Williams’s “rhetoric” in Spring and All, as opposed to what they understood to be “poetry,” by which they meant lyric or lyric-adjacent poems, taken out of their context in the work as a whole. If, indeed, poetry is a font among several “fonts of rhetoric,” as Bernstein suggests, then the separation was incomprehensible to begin with. If there is some precedent for what Bernstein so often does in mixing poetry and criticism in Williams’s work, and especially in a text like Spring and All, then it is here that we find it. As Alan Golding has pointed out, for Bernstein, “Williams’s disjunct critical prose influences later prose poetry” (2022: 207). Bernstein has developed the call for the blurring of boundaries much further, but the impulse was there in Williams’s work too. As Hazel Smith has argued, “Bernstein’s enthusiasm for Williams’s work stems at least partly from Williams’s penchant for the unusual and his contempt for a passive acceptance of traditional conventions” (2024: 33–34).

In thesis fifty-eight of “95 Theses,” Bernstein states that “the aversion of disciplinarity requires discipline” (2024a: 18). This aversion was shared by Williams, who wanted to tear down the walls between disciplines to create interactions between English and the sciences, and to whom thesis fifty-seven would also have made perfect sense: “Redefine English in ‘English department’ as the host language not the disciplinary boundary, where English is understood neither as origin nor destination” (Bernstein 2024a: 18). Williams was thinking along the same lines. In the piece “(A Sketch for) The Beginnings of an American Education” in the posthumously published The Embodiment of Knowledge, largely composed in the 1920s, Williams too questions the emphasis on English: “A good beginning in this case would be to abolish in American schools (at least) all English departments and to establish in [their] place the department of Language—of which the English could be a subsidiary—one of the divisions—or not, as it may be desired” (1974: 146). “It is not a language that is desired—but language,” Williams stresses (146). As for the centrality of literature, “all scholarship begins” in “the department of letters” (147). In “Frame Lock,” an essay that began as an MLA speech and upon which the ninety-five theses constitute a comment, and which relies on ideas from Goffman’s Frame Analysis, Bernstein even suggests that English should be seen more as “the host language” of a course of study that is actually about literature in a broad sense, about the humanities, and the history of ideas (1999: 96). Indeed, that students should read beyond literature in English and also delve into other literatures, including, but not limited to, continental European literature. The Bernstein of “Frame Lock” is reminiscent of the Williams of The Great American Novel, with the use of an antagonistic voice built into the text, constantly questioning the writer, asking things like “But aren’t you conflating literary and academic writing?” (1999: 97). In Williams’s 1923 anti-novel, the mocking, questioning voice says: “Do you mean to say that art does any WORK?” to which Williams’s speaker replies “—Yes” (1970: 170). These voices in opposition represent the traditionalist views maintaining the hegemonic status quo of academic discourse as well as of poetry.

The speech delivered at the 2023 MLA Convention ended up not being collected in a Special Issue I was editing for The William Carlos Williams Review on the same topic, as Bernstein rightly saw his new book as the necessary context for the essay. For Bernstein, as we know, the context matters and is essential for the constellation. It forms a frame, just like the MLA convention itself does, and this movement between frames, and from speech to text, is in itself crucial. When I first asked him if he would consider doing something on the anniversary of his 1983 MLA talk, he wrote, characteristically, “put me down for ‘The Academy [Still] in Peril: William Carlos Williams Meets the MLA at 40.’ As I type that, I can feel a whole ’nother speech coming on!” (pers. comm., February 25, 2022). Sure enough, by the time of the conference, the title of the presentation had been changed to “Free Thinking: Spring and All versus The Waste Land at 100,” like the essay now featured in The Kinds of Poetry I Want. A shift in frame, yet again.

At the beginning of this essay, I stated that Bernstein often mentions Williams in The Kinds of Poetry I Want. A glance at the index, in a number game gesturing to the one Bernstein himself performs in the essay “Free Thinking,” with its “highly unreliable tally for the combined mentions of a poet by the New Yorker and New York Review of Books” (2024a: 159), reveals Williams’s place in the larger ecology of references, with Eliot appearing on nine of the book’s pages, Pound on twenty, and Stein on thirty-one. Williams appears on sixteen, coming in ahead of Eliot, but after Pound and Stein. Even if Williams is not the most frequently mentioned poet in The Kinds of Poetry I Want, there is an unmistakable kinship in the insistence on aesthetics, in how poetry matters as form. As Bernstein admits in the essay he ended up writing for the Special Issue of the William Carlos Williams Review, “It’s the performative nature of Spring and All that inspired me” (2024b: 93). Much of the prose in Spring and All is devoted to a testing of the boundaries between poetry and prose, a teasing out of the potentialities of forms of language. Williams concludes that poetry is “new form dealt with as a reality in itself,” as opposed to prose, which is “statement of facts concerning emotions, intellectual states, data of all sorts—technical expositions, jargon, of all sorts—fictional and other—” (1986: 219). As for the form of poetry, to Williams, it “is related to the movements of the imagination” (219). He writes: “Poetry is something quite different. Poetry has to do with the crystallization of the imagination—the perfection of new forms as additions to nature—prose may follow to enlighten but poetry—” (226). On the formal difference between poetry and prose, Williams proposes that “form in prose ends with the end of that which is being communicated” (226). It is always tempting to focus on Bernstein’s recurring discussion of the opposition between the lyric poetry condoned by official verse culture, on the one hand, and avant-garde poetry on the other, in terms of the former’s reverence for personal experience and sincere feelings and the latter’s insistence on form and materiality. However, this opposition is in many ways just a prelude to the most intriguing aspect, which, to me, is the exploration of poetry’s aesthetic affordances. In “The Swerve of Verse,” discussing Lucretius, Bernstein contends that Lucretius’s “verse . . . is there to ensnare, to pull readers into an aesthetic/conceptual experience that cannot be put into prose. It goes beyond the resources of prose in making palpable its (initially) counterintuitive philosophy. . .” (2024a: 111).

If The Kinds of Poetry I Want promises a poetics, the essay “Offbeat,” offers a relatively clear summary of what that poetics might entail: “I want poems that are ecstatic in the sense that they exceed moral and political discourse. Poems as sensation, as performance, as aesthetic, doing rather than stating” (2024a: 33). Exceeding the bounds of discourse, breaking frames, and cumulatively moving through contexts in shifting constellations, propelled by but also critically interrogating the resources of our ever-expanding media ecology—such, it seems to me, are the kinds of poetry Charles Bernstein wants. And while there are important points of divergence and significant differences between the two—surely enough to fill at least a couple of essays—by and large, Williams would probably have agreed.

References

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. 1981. “Discourse in the Novel.” In The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays by M. M. Bakhtin, edited by Michael Holquist. Translated by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist, 259–422. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Bauman, Richard, and Charles L. Briggs. 1990. “Poetics and Performance as Critical Perspectives on Language and Social Life.” Annual Review of Anthropology 19: 59–88.

Bernstein, Charles. 1999. My Way: Speeches and Poems. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bernstein, Charles. 2001. Content’s Dream: Essays, 1975–1984. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. Originally published in 1986 by Sun & Moon Press, Los Angeles.

Bernstein, Charles. 2011. Attack of the Difficult Poems: Essays and Inventions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bernstein, Charles. 2016. Pitch of Poetry. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bernstein, Charles. 2018. Near/Miss. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bernstein, Charles. 2021. Topsy-Turvy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bernstein, Charles. 2024a. The Kinds of Poetry I Want: Essays and Comedies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bernstein, Charles. 2024b. “Which Side Are You On?” The William Carlos Williams Review 41, no. 1: 86–96.

Goffman, Erving. 1986. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Boston: Northeastern University Press. First published in 1974 by Harper & Row.

Golding, Alan. 2022. “‘What About All This Writing?’: Williams and Alternative Poetics.” In Writing into the Future: New American Poetries from the Dial to the Digital, 197–217. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. The essay was first published in Textual Practice 18.2 (2004): 265–282.

Perloff, Marjorie. 2021a. “‘Funny Ha-Ha or Funny Peculiar?’: Recalculating Charles Bernstein’s Poetry.” In Evaluations of US Poetry Since 1950, Volume 1: Language, Form, Music, edited by Robert von Hallberg and Robert Faggen, 221–244. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Perloff, Marjorie. 2021b. Infrathin: An Experiment in Micropoetics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Smith, Hazel. 2024. “No Ideas but in Technology: William Carlos Williams, Concepts of the New, and Electronic Literature.” The William Carlos Williams Review 41, no. 1: 30–57.

Williams, William Carlos. 1969. Selected Essays. New York: New Directions.

Williams, William Carlos. 1970. Imaginations, edited by Webster Schott. New York: New Directions.

Williams, William Carlos. 1974. The Embodiment of Knowledge, edited by Ron Loewinsohn. New York: New Directions.

Williams, William Carlos. 1986. The Collected Poems of William Carlos Williams: Volume 1, 1909–1939, edited by A. Walton Litz and Christopher MacGowan. New York: New Directions.

Notes

[1] Alan Golding (2022) clarifies the relationship between Spring and All and the merging of poetry and criticism in Bernstein’s and other Language writers’ work excellently in an essay whose title also zooms in on that very same Williams quote from Spring and All.

[2] This panel resulted in a Special Issue of The William Carlos Williams Review, in whose introduction I write more about the historical moment in 1983 and its relation to the 2023 panel. See “Spring and All no Longer in Peril.” The William Carlos Williams Review 41, no. 1 (2024): 1–11.

[3] While I here consider excess in relation to sheer mass, it has previously been used to describe Bernstein’s poetry and what Perloff has termed its “baroque excess” (Perloff 2021a: 238).

[4] For a discussion of this alleged “formlessness,” see Perloff 2021a: 222.

[5] To be sure, Williams knew how to make use of the preface as a space for artistic innovation, not least in the prologue to Kora in Hell that includes letters from Pound, Stevens, and H.D., but also in the preface-like introductory section of Spring and All in which he simply declares about his ensuing experimental work that it is likely that “no one will want to see it” (1986: 177).