by Nathan Brown

The body is the inscribed surface of events (traced by language and dissolved by ideas), the locus of a dissociated Self (adopting the illusion of a substantial unity), and a volume in perpetual disintegration.

– Michel Foucault, “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History”[i]

A troubling and enabling fact about the body is that it is never exactly “here” nor “there.” The existence of the body evades its coincidence with language, with thought, with the I, such that it can be described as “the locus of a dissociated Self.” The body is the self, but it is the self as dissociated. Its existence is an index of the dissociation the self is, of the self’s non-identity with itself, with language, and with thought.

Writing on Nietzsche’s physiological attunement to philosophical thinking, Foucault offers three determinations of the body: 1) the inscribed surface of events; 2) the locus of a dissociated Self; 3) a volume in perpetual disintegration. These determinations abjure the apparent self-evidence of the body’s organic integrity (“the illusion of substantial unity”) in order to consider it as the site of certain operations (inscription, dissociation, disintegration) and as a spatially extended object (surface, locus, volume). The body records events and it instantiates the self’s dissociation. It holds together the dissociated self with those events that traverse it, but the very site of this holding together, its volume, is at the same time coming apart, disintegrating. Language traces events inscribed on the body; ideas dissolve them. Language and ideas separate events from the body, from the surface upon which they are inscribed, exteriorizing their inscription (tracing) or absorbing them into thought (dissolution). The perpetual disintegration of the body is the process by which the surface of its volume ceases to make available such exteriorization or absorption. The disintegration of the body is the gradual coming undone of language and of thought, of the registration of events.

How might we situate art with respect to these determinations of the body? As a practice, art takes place at the boundaries of language and thought: it is involved with language and thought, yet not (only) linguistic or ideational. To describe the body as “a volume in perpetual disintegration” is to consider it formally: disintegration implies a measure of integration, and this measure, considered as volume, is form. Can this disintegration of form be exteriorized? As the body disintegrates, can it produce a double of its disintegration? Or, if not a double, at least a counterpart, a semblable? If philosophy takes place as the conjunction of language and thinking, how can art, at the boundaries of philosophy, disjoin these by doubling the perpetual disintegration of the volume that the body is, by displacing the locus of a dissociated self?

These are the questions that will guide my approach to the art practice of Alexi Kukuljevic,[ii] through which I hope to limn a certain science of the logic of disintegration.

CAPUT MORTUUM

At Caput Mortuum, Kukuljevic’s solo show in 2012, a plaster cast of the artist’s teeth, his bite, sits atop the highest plinth in the room, spray painted gold and titled The Subject-Object (Fig. 1). The cast displays a pronounced overbite, the upper incisors caving in at the center and thus protruding out diagonally at irregular angles. On a plinth behind and to the left, another cast of the same teeth is presented at the opening of the show, this time in frozen black ink resting on a neon green edition of Hegel’s Phänomenologie des Geistes. The piece is titled The Object-Subject (Fig. 2 & 3). As the duration of the opening unfolds, the frozen cast melts into a liquid black pool, soaking the book beneath and forming a minimally differentiated volume of black ink against the background of the black plinth below. Watching over this process of disintegration from the wall above is a silkscreen print of Hegel’s portrait, his forehead exhibiting an unseemly goiter of spray foam with a nail driven through its center, neon green paint seeping from the wounded brow of the great thinker, running over the left eye and down the philosopher’s face across the surface of the print.

This configuration establishes a basic dialectic of the artist’s practice. A singular or signature trait of the artist’s embodied subjectivity—his irregular bite—is cast as a sculptural object and presented to the viewer’s eye coated in the color of value, gold. A frozen double of this object, cast in the color of negation and the medium of inscription—black ink—displays the impermanence of its objecthood, the temporal finitude of its form, by melting into an indistinct pool. The subject becomes object on the condition that the object becomes subject, yet the doubling of the object (molded in plaster as well as black ink) enables it to sustain its form even as it melts into fluidity. The formal and fluid excess of this doubling is suggested by the seepage of paint from the pierced surface of Hegel’s printed portrait, as if the provocation of the thinker’s absolute judgment—that “the being of Spirit is a bone” (Hegel 1977 [1807]: 208)—called for a trepanation, by way of verification. Can we find the substance-subject in the skull? In the Phenomenology’s chapter on “Observing Reason,” philosophy reaches the point at which thought thinks its unthinking substrate and thus sublates that substrate as thought. It then becomes the vocation of art to render the residue of this sublation—the persistence of thought’s unthinking body—as the obdurate, curiously inconceivable, condition of its possibility.

Art thus inhabits the disjunction between the highest and the lowest, the spiritual fulfillment of self-comprehending life and the physical function, as Hegel puts it, of taking a piss (210).[iii] From the point of view of philosophy, it “must be regarded as a complete denial of Reason to pass off a bone as the actual existence of consciousness” (205). From the point of view of art, the materials in which consciousness is inscribed are the ineliminable ground of formal specificity. “The body” is a relay between subject and object, but one that cannot simply be “lived.” Thinking itself as a thing that thinks, the thinking thing finds its particularity in the material substrate and remainder of this operation: not just any skull, but this skull; this skull which is, impossibly, “mine.” “My body” is that which is not (quite) either mine or me, yet which is I. The being of Spirit is not just any bone. What dissolves into fluidity through the becoming subject of the object, or resolves into solidity through the becoming object of the subject, is the specificity of these teeth, the irregular contours of this bite, and it is on the condition of encountering resolutely material form that universality can include particularity.

Within the cut between the Subject-Object and the Object-Subject, art tarries with this relay between the specificity of the material particular and its insistence, as specific, within the genericity of the universal. This is one of the rifts that art inhabits.

RIFT

Absolute knowledge requires the reconciliation of subject and object. This is not an option for art. If art knows anything (this is unclear) it is that the subject can not even be reconciled with itself, let alone with the object. The art object is an unreconciled remainder of the rift between the I and the Me. “Me” is the object form of the pronoun “I.” When I say “I,” the “me” is the unfortunate residue of my enunciation. “I = I” enunciates the genesis of the subject, but, for better or for worse (for worse), the subject has a body that remains unequal to the equals sign, that is unreconciled with the I to which it supposedly belongs. There “I” am (me), just when I hoped to be “here.” The golden egg of self-equivalence is held aloft (Fig. 4), supported by the doubled singularity of the irregular bite, by the mold of the split jaw that is the ground of articulation, the structure of the mouth, the condition of enunciation, or “The Limits of Grammar” (as another title has it).

I = I splits into the dissociation of the I and the Me, held together as the body, exteriorized as the art object — the residue of such dissociation. In A Little Game Played Between the I and the Me, Kukuljevic’s contribution to the Nouvelles Vagues show at Palais de Tokyo in 2013 (Fig. 5), the central piece titled The I and the Me consists of two formally similar but morphologically discrepant sculptural masses, one of which is placed solidly upon a pedestal while the other hangs precariously from its edge, as if having just climbed up on stage or about to fall off.

From a speaker within these asymmetrically relational forms, not-quite mirror images, a slow, dry, tired voice emanates into the gallery space:

I say: I, I, I. You say: me. Me say, you. You say: I, I, I. I say, me.

You answer to human. You grind your teeth. You point with the jaundiced nub of a finger. Your jaw drops on its hinge. Your thumbs bend at the joint. You toss word upon word. Live in abstraction. Skip stones. Sip whiskey. Polish silver. Lay claim to the luxury of fine cotton. Vomit champagne. And know how to sharpen the blade.

….

There is an unease in your cadence. Your pace is hobbled. Your bones lack alignment. Your stare a milky grey. That hole in your head oozes something unrefined. Something is making you reach for your nail file. Adjust your posture. (Kukuljevic 2013)

Art is a pastime, a distraction, an indulgence, or a chore, like skipping stones, sipping whiskey, or polishing silver. It is a luxury, a guilty pleasure, like fine cotton or champagne, yet also something of an impediment, a burden, a limp, or perhaps the cane a limp requires. The hangover after the champagne. It is at once a decadent practice and the tick of the uneasy, the correlate of both the hobbled pace and the easy profligacy of the dissolute aristocrat. A goiter. A gouty toe. An overgrowth. Something that makes you reach for your nail file. It can hardly keep its balance on the pedestal upon which it is placed. The I stands firm, but the Me falters. Or the Me pretends to solidity, as the I wavers. Art is the imbalance of their mutual reckoning, their teeter-totter, the milky grey substance of their self-regarding stare, the hinge upon which the jaw issues abstractions, the sharpened blade with which one arm stabs the other.

The rift between the I and the Me is the rift within the I = I, and consciousness of this rift demands its object, “the locus of a dissociated Self,” in order to convey its dissociation. The recognition of this dissociation solicits its displacement. Yet the object into which this locus is displaced must itself be doubled if it is not merely to suggest an exteriorization of the self, but rather the exteriorization of the self’s dissociation. The doubling of the object is the double of the dissociated (rather than unified) subject. Art which knows the riven conditions of its own possibility duplicates the singular form of its object, breeds its replication, demands reiteration, refuses the originality of the origin. Art repeats.

(C8H8)n

In his sculptural work, Kukuljevic’s preferred material is styrofoam (expanded polystyrene).[iv] The I and the Me, for example, is composed of rectangular polystyrene panels stacked unevenly or clumped together vertically, coated with cement, and globbed with spray foam. Kukuljevic shapes the material by cutting it, burning it with a blowtorch, or melting it away with acetone, a substance with roots in alchemical practices (see Gorman and Doering 1959). Thus, one of The Subject’s Alchemical Residuals (Fig. 6) is a curved wedge of styrofoam with a conical hole melted through its center, the pocked surface around the base of the conical hollow marking the damage done by splashes of the corrosive substance. Like The Subject-Object and The Object-Subject, this might be read as something of a demonstration piece, a formal synechdoche or concentrated reduction of the artist’s concerns and methods, a minimal unit of his practice.

The subject makes a hole in the object, which thus becomes an art object. The hole is not made by digging, by a practice of removal that would merely shift its material off to the side. It is made by dissolution, dissipation, dispersion: the hole itself, not the material subtracted from it, is the visible remainder of its production. What is produced is not a pile but an absence, a negation. The material bears the trace of this negation without remainder; that which remains is spirited away. Thus the art object becomes the residue, the residual, of an act of negation, its damaged remnant. It is an alchemical residual insofar as, qua art object, it has acquired value. Value is acquired by the material remnant of the negation of matter; it is its immaterial companion, inscribed as an absence within the object that makes it art.

If the production of acetone has its roots in premodern alchemical practices, the production of polystyrene (beginning in the 1930s at IG Farben and 1941 at Dow Chemical) can be traced to the emergence of aromatic polymer chemistry, predicated upon Kekulé’s modeling of the benzene ring in 1865, and thus coeval with Marx’s theory of the commodity. The coincidence is merely suggestive, yet the chemical fabrication of organic compounds (“synthesis”) shadows the history of real subsumption and the attendant rise of mass consumption like an uncanny double (see Leslie 2005). Not only industrially produced objects but the molecules of which they are composed become artificial. Marx tells us that

If we subtract the total amount of useful labor of different kinds which is contained in the coat, the linen, etc., a material substratum is always left. This substratum is furnished by nature without human intervention. When man engages in production, he can only proceed as nature does herself, i.e. he can only change the form of the materials. (Marx 1990 [1867]: 133)

This remains the case, but with the rise of chemical synthesis the production of the material substratum itself becomes a matter of labor, such that the only remaining substratum “furnished by nature without human intervention” are atoms of carbon and hydrogen — not even the molecular forms in which these are combined. As if in uncanny response to the metaphorical provocations of Marx’s chemical analogies in the first volume of Capital, the commodity becomes artificial in its very substance. The abstraction of socially necessary labor time saturates not only the object produced from natural materials, but also the molecular structure of the materials themselves, such that even the latter are soaked in the immaterial substance of value.[v] “It is absolutely clear,” writes Marx,

that, by his activity, man changes the forms of materials of nature in such a way as to make them useful to him. The form of wood, for instance, is altered if a table is made out of it. Nevertheless, the table continues to be wood, an ordinary, sensuous thing. But as soon as it emerges as a commodity, it changes into a thing which transcends sensuousness. (163)

Synthetically produced organic compounds, such as polymers, are in this sense not “ordinary sensuous things” (“materials of nature”) but rather materials that already “transcend sensuousness,” materials that are never not already commodities. Not only the process of production but also the materials upon which it works are fully subsumed.

Thus a styrofoam cup is a commodity made of a material that has no “natural” existence outside of the commodity form, as is a polyester dress. So is a rectangular panel or a molded form of expanded polystyrene packaging material, but in this case the relation of the commodity to its consumption is rather curious. Here we are dealing with a commodity whose use value is to protect commodities as they circulate. A consumer buys something else, and some styrofoam comes with it, a necessary if unwanted accompaniment. Indeed, styrofoam packaging is in a particularly abject position insofar as it does not even carry out the other functional purpose of packaging, that of advertising the product within, in the manner of the all important box. Styrofoam is a mere intermediary between the alluring surface of the disposable exterior and the desirable utility of the interior object. A material byproduct of circulation, expanded polystyrene packaging is both invisible at the point of sale and already waste at the point of consumption. Even the consumer’s cat, who loves to sleep in cardboard boxes, wants nothing to do with molded styrofoam once it has been cast aside. Artificial even in its molecular constitution, unwanted by the consumer to whom it is destined, expanded polystyrene packaging is the paradigmatically unnatural detritus of the capitalist transformation of nature.

The rendering of this destitute material as art is its salvation, or one more indignity to which it is subjected. At last, in any case, it is put on display, forming the curious substance of something someone might even buy.

PERSONAE

In the hospital rooms on either side, objects—vases, ashtrays, beds—had looked wet and scary, hardly bothering to cover up their true meanings. They ran a few syringesful into me, and I felt like I’d turned from a light, Styrofoam thing into a person. I held up my hands before my eyes. The hands were as still as a sculpture’s.

– Denis Johnson, Jesus’ Son

“From a light, Styrofoam thing into a person”: Kukuljevic’s art practice reverses this conversion. The movement from person to styrofoam thing is productive not only of sculpture, but also of personae: those artificial figures of personhood through which one presents oneself to the public.

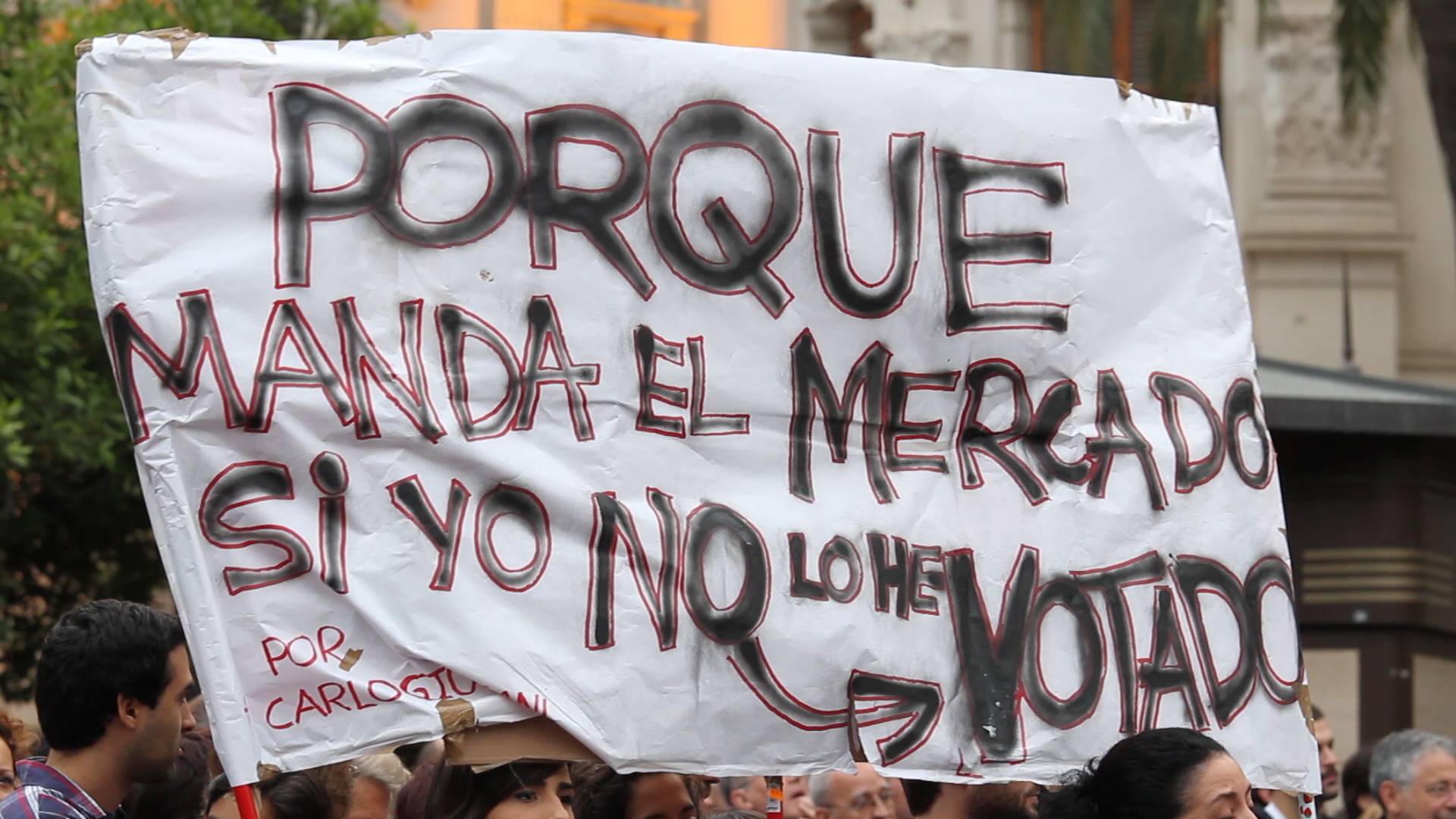

Spending some time at his 2012 solo show, Don’t Be a Dreamer, Mr. Me, one comes to feel an odd sense of consolation among its major pieces: An Orgy of Stupidity (Fig. 7); Idiot (Fig. 8); A Gangrenous Fop (Fig. 9). The titles suggest a shared lack of intelligence, foregrounding a common trait of cognitive degeneracy. Indeed, not much can be expected by way of sparkling conversation from chunks of burned and painted styrofoam. “Everything about the show appears to be unhealthy — mentally and physically,” found one reviewer (Schwartz 2013). It is true, a sojourn among these initially unattractive, mildly poisonous forms seems not to promise the edification of a trip to the gym or the library. Yet one nevertheless develops a certain fondness for them, this cast of characters; an improbable affection gradually accrues in their mere presence.

Deleuze recognized that stupidity is both the enemy of and the condition for philosophical thinking. One thinks in order to combat stupidity, yet in order to begin thinking at all, one has to be stupid. There must be an interruption of the order of the given, of the already known, of what Deleuze called “the image of thought” in order for thought to encounter its own ungroundedness: in order for thought to know that it does not know, and thus begin to think. In order not to be stupid, one has to be stupid: this is a contradiction with which philosophy has been embroiled since Socrates. What Konrad Bayer called “the sixth sense,” says Kukuljevic, involves “knowing when to risk being a dummy” (Kukuljevic, 2013-2014). But Deleuze goes beyond merely knowing when to take this risk, claiming that “Stupidity (not error) constitutes the greatest weakness of thought, but also the source of its highest power in that which forces it to think” (Deleuze 2004 [1968]: 345). Just as “the mechanism of nonsense is the highest finality of sense,” he argues, “the mechanism of stupidity (bétise) is the highest finality of thought” (193).. Do these styrofoam forms impart some of their stupidity to the viewer? Do they thus solicit thinking?

One notes their vaguely anthropomorphic aspect. An Orgy of Stupidity looks like an enormous malformed grey skull accosted by pink spray foam, brooding dull-wittedly upon its table. Holes are melted into the “front” of the piece, resembling hollow eyes, while deeper crevices puncture it behind and below, visible when viewed in the round. Deceptively simple, the formal construction of the piece is in fact carefully articulated. Positioned at the back of the room, the bulk of this sculpture anchors the space, at once drawing the gaze and looking on, surveying the assembled art without having much to say about it. The show seems to turn upon this piece, a dead-head like a humanoid boulder measuring the depth or frivolity of our contemplation, of our chatter, against the taciturn obduracy of its inorganic impassivity.

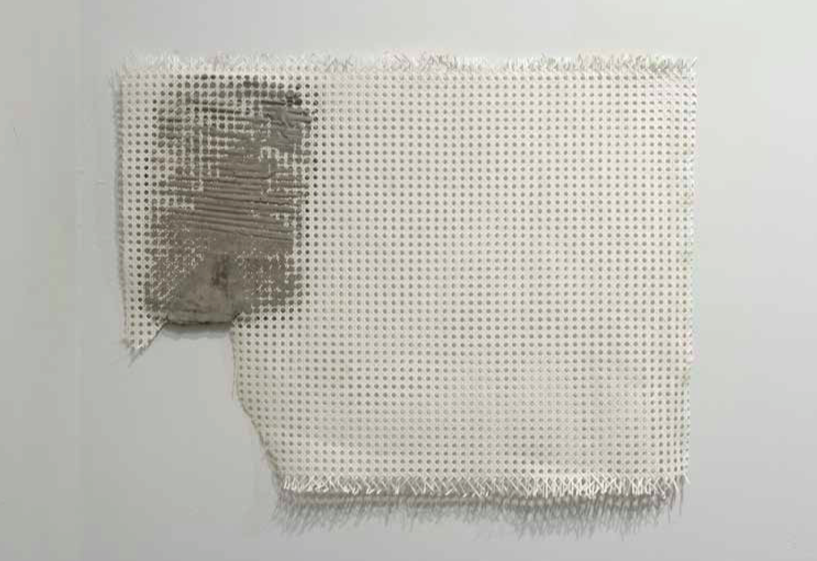

While An Orgy of Stupidity rests solidly upon its base, Idiot is propped against a load-bearing column, while the large, roughly rectangular form of A Gangrenous Fop balances upon a single dowel anchored in a styrofoam base resting on a plinth. The fragile support of the latter piece drives home the lightness of what seem to be massive forms, the interior airiness of imposing exteriors, often sealed with a layer of concrete. This counter-intuitive play between the heaviness of surface and the lightness of depth is mediated by the technique and motif of perforation running through Kukuljevic’s practice. It is enacted by his melting away of surfaces in order to bore into sculptural forms and also thematized in wall pieces involving concrete and chair caning (Fig. 10), a material he values for the concomitant complicity and cancellation of surface and depth suggested by its woven form.

The surface is more weighty than the interior — that is the sort of judgment one might venture looking at a piece like A Gangrenous Fop, with its lightly balanced heft. Yet the concrete surface itself is punctuated by holes that confuse or undo this distinction, leading us into the form along its surface in pursuit of depth, which thus becomes surface. Likewise, the use of spray foam to combine sculptural masses and to fill in crevices between them suggests an eruption — or at least a slow, coagulating leakage — of the interior. Meanwhile, color mediates this formal dialectic. Synthetic, superficial fluorescent shades seep from interiors or coat their exposed crevices, highlighting absences opened by corrosion, or the white sublation of color constitutes a pure yet perforated surface through which solid grey concrete seeps.

If the somewhat familiar sculptural forms (one of them is titled A Human-Like Creature) exhibited at Don’t Be a Dreamer, Mr. Me come to seem sympathetic, perhaps it is because they have been through so much. Punctured, corroded, seeping foam and stained with garish colors, carefully poised or precariously propped up, they have an air of weary endurance about them, as if about to collapse or retire yet in for the long haul by virtue of their molecular inertia and their improbable value as art. They seem fated to be tired for a long time, with no choice but to make a display of themselves. This wry anthropomorphism solicits transferential self-pity, such that a title like Idiot may come to feel like a way of insulting the audience — a rhetorical inclination to which Kukuljevic is happily prone. In the end one takes it well. There is something like a communal self-loathing to be gleaned from such a show, the circulation of self-recognition as the concession of its weary stupidity, its dissolution (Fig. 11).

Given the dissociation of the self, its perpetual disintegration, perhaps an encounter with the stupidity of self-recognition is one among the most precious objects art has to offer — or at least its most sincere gift. It snaps one out of a bland tete-â-tete with oneself, or with another, such that one begins to think. We come to feel affection for the forms that gift takes.

SMOKE

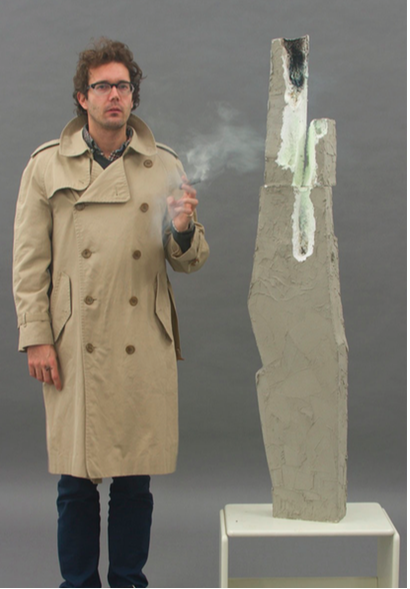

Having started with bone, why not end with breath? Both have been said to be spirit. Yet even as Hegel could subsume the materiality of the skull within the ideality of the concept, breath is a materialization of the ineffable. This is a recognition readily available amid a cloud of cigar smoke, which constitutes for Kukuljevic not only a medium in its own right but a method of attunement, a dissociated Stimmung:

Trapped between index and middle finger, a cigar traces a delicate line, its stump more unseemly. However, if held with poise, a cigar is a simple and elegant machine, much like a crowbar, that provides the mind with the material impetus for prying off an impression of the soul, as one peels off a latex mold.

“Each cigar is a snapshot,” he writes, “of the soul’s decomposition” (Kukuljevic 2014). The cigar is a prop, like a sculpture. Yet it is a prop whose substance becomes interchangeable with that of the subject who wields it, to the detriment of both the subject and the object. The cigar is the temporary site of a chiasmus whereby both the subject and the object burn down to a material remainder, the former more slowly than the latter but no less surely. The billowing form of the cloud of smoke “focuses the mind on life’s dissipative march” (Fig. 12).

Marcel Duchamp understood the pitfalls of relating to art primarily through the figure of the object, or “the art object.” For if something is an object, how can it be art? And if it is art, how can it be an object? Implicit in these questions is the immaterial surplus exhaled by any object that comes to be called “art,” the ineffable imprimatur invisibly stamped upon that which the term designates, an imprimatur that converts it into something other than what it is. Duchamp thus focused his attention upon what he called the infra-thin: “when the tobacco smoke smells also of the mouth which exhales it, the two odors marry by infra-thin.” The two odors, he says. Yet this figure of the infra-thin involves not only a marriage of two odors, but also of the object, the subject, and the fumes it exhales, mediated by the corporeal hollow of the mouth. Here the infra-thin is a complex of the subject-object, or the object-subject, which entails not only the ephemeralization of the corporeal but the corporealization of the ephemeral, a physics of the metaphysical and a materialization of the ideal, like “prying off an impression of the soul, as one peels off a latex mold.”

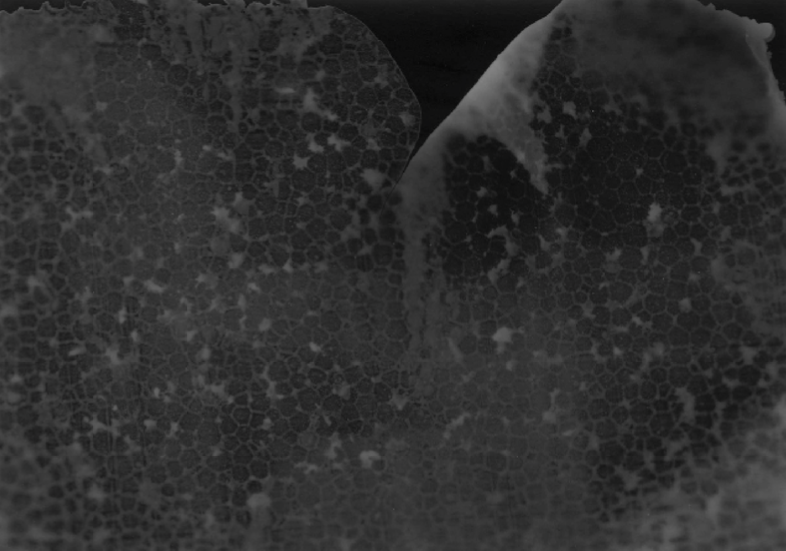

If the smoking of cigars is properly considered part of Kukuljevic’s art practice (evident in his habit of filling the gallery with cigar smoke before openings), the photogram is its saleable analog (Fig. 13 & 14). Like his silkscreen prints of coral, or his wall sculptures with chair caning, his photograms tarry with the perforations constitutive of surface and with the permeability of the object. Just as the cigar burns into ash, a fragile record of its temporal dispersion, the retentional action of the photogram gives us to see the legible transparency of material structure, the ghost of the incorporeal that haunts all bodies.

Yet the record of the cigar’s dispersion, its ash, is also its material residue — like styrofoam packaging that arrives alongside the consumer’s commodity. It needs somewhere to end up, to repose, and thus calls not only for the light touch of the photogram but also the hospitable embrace of the ashtray (Fig. 15). The propped up body of the sculpture would then support the papery corpse of the cigar, leaving the viewer to contemplate the degree to which form follows function in the case of so fleshly a friend of the infra-thin. This is the highest form of practicality we will encounter in Kukuljevic’s practice: the making of a place, barely contained within itself, to put the leavings of disintegration. Perhaps “the object” is better understood as such a place — and this is the sort of place, indelicately distended and on the verge of collapse, that the artist might call art.

It is in this sense that I view Trading Places (Fig. 16) as a particularly notable piece in Kukuljevic’s oeuvre. Whereas most of the sculptural works are either tenuously propped or heavily settled, this one rests upon a stable base, yet one that is mobile. Its form is again vaguely anthropomorphic, but in this case diminutive — a sidekick of sorts, like Lear’s clever fool or an R2D2 suffering the fate of Tithonus. The figure is burned out, carved away, its interior exposed and its surface rough-hewn, yet its dominant shade is a light azure that lends it a certain celestial freshness amid the charred remains it barely holds together. At the center of the piece, the same thin wood stick that bends under the burden of supporting some of the sculptures in this case holds aloft its own offering, cradled in a bright yellow latex glove, as if in supplication of the viewer. Here, the piece seems to intimate, this is what I have for you.

What is thus presented is a bit of ash, the stump of a cigar, cupped within an indeterminate grey residue. Perhaps this is a present, maybe a presentiment. Sculpture, trading places, offers up a volume in perpetual disintegration as if posing its own question to the viewer, to the body of the subject who is not allowed to touch it: what do you have to offer me?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Deleuze, Gilles. Difference and Repetition. (1968). Translated by Paul Patton. London: Continuum, 2004

Gorman, Mel and Charles Doering. “History of the Structure of Acetone.” Chymia. 5 (1959): 202-208.

Hegel, G.W.F. Phenomenology of Spirit. (1807). Translated by A.V. Miller. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977

Kukuljevic, Alexi. Audio Track, A Little Game Played Between the I and the Me. Nouvelles Vagues, Palais de Tokyo, 2013.

Kukuljevic, Alexi. Exhibition Text for Don’t Be a Dreamer, Mr. Me. (December 6, 2013 – January 19, 2014). http://www.marginalutility.org/exhibitions/2013/alexi-kukuljevic-dont-be-a-dreamer-mr-me/.

Kukuljevic, Alexi. “More or Less Art, More or Less a Commodity, More or Less and Object,More or Less a Subject: The Readymade and the Artist” in The Art of the Concept. Edited by Nathan Brown and Petar Milat. Frakcija 64/65 (2013): 62-70.

Kukuljevic, Alexi. Exhibition Text for You Can’t Rely on the Joke as the Only Mode of Social Relation…. (March 14 – April 30, 2014). http://www.kunsthalle- leipzig.com/kukuljevic.html

Leslie, Esther. Synthetic Worlds: Nature, Art, and the Chemical Industry. London: Reaktion Books, 2005.

Marx, Karl. Capital: Volume 1. (1867). Translated by Ben Fowkes. New York: Penguin, 1990.

Schwartz, C. “Alexi Kukuljevic Dares Not to Dream at Marginal Utility.” Knight Blog (December 10, 2013). http://www.knightfoundation.org/blogs/knightblog/2013/12/10/alexi-kukuljevic-marginal-utility/

NOTES

[i] Thanks to Petar Milat for drawing my attention to this passage.

[ii] Kukuljevic’s work has been included in exhibitions at Tanya Leighton Gallery (Berlin, 2016), Kavi Gupta (Chicago, 2015), Palais de Tokyo (Paris, 2013), De Appel (Amsterdam, 2012), and has been shown in solo exhibitions at Å+ Gallery (Berlin, upcoming 2016), Kunsthalle Leipzig (2014); ICA Philadelphia (2013), Jan Van Eyke Academie (Maastrict, 2013), and SIZ Gallery (Rijeka, 2012). He holds a Ph.D. in Philosophy from Villanova University, where he wrote a dissertation titled “The Renaissance of Ontology: Kant, Heidegger, Deleuze” (2009). He was a researcher at Jan Van Eyke Academie (2012-2013). His book Liquidation World: On Forms of Dissolute Subjectivity is forthcoming with MIT Press. He is the author of an artist’s book, Cracked Fillings, available at alexikukuljevic.com.

[iii] Hegel writes, “The infinite judgement, qua infinite, would be the fulfilment of life that comprehends itself; the consciousness of the infinite judgment that remains at the level of picture-thinking behaves as urination [verhält sich als Pissen]” (210).

[iv] Strictly speaking, “Styrofoam” is the brand name of extruded polystyrene produced exclusively by Dow Chemical, which is used in craft and insulation applications and is usually blue or green. The term is more loosely and commonly applied to expanded polystyrene in general, such as that used for foam cups or molded packaging. Following this common usage, I will refer to expanded polystyrene and styrofoam interchangeably.

[v] Kukuljevic has published an essay on the relationship between the commodity form, the readymade, and the figure of the artist. See Kukuljevic 2013.