a review of Mark Jarzombek, Digital Stockholm Syndrome in the Post-Ontological Age (University of Minnesota Press Forerunners Series, 2016)

~

All existence is Beta, basically. A ceaseless codependent improvement unto death, but then death is not even the end. Nothing will be finalized. There is no end, no closure. The search will outlive us forever

— Joshua Cohen, Book of Numbers

Being a (in)human is to be a beta tester

— Mark Jarzombek, Digital Stockholm Syndrome in the Post-Ontological Age

Too many people have access to your state of mind

— Renata Adler, Speedboat

Whenever I read through Vilém Flusser’s vast body of work and encounter, in print no less, one of the core concepts of his thought—which is that “human communication is unnatural” (2002, 5)––I find it nearly impossible to shake the feeling that the late Czech-Brazilian thinker must have derived some kind of preternatural pleasure from insisting on the ironic gesture’s repetition. Flusser’s rather grim view that “there is no possible form of communication that can communicate concrete experience to others” (2016, 23) leads him to declare that the intersubjective dimension of communication implies inevitably the existence of a society which is, in his eyes, itself an unnatural institution. One can find all over in Flusser’s work traces of his life-long attempt to think through the full philosophical implications of European nihilism, and evidence of this intellectual engagement can be readily found in his theories of communication.

One of Flusser’s key ideas that draws me in is his notion that human communication affords us the ability to “forget the meaningless context in which we are completely alone and incommunicado, that is, the world in which we are condemned to solitary confinement and death: the world of ‘nature’” (2002, 4). In order to help stave off the inexorable tide of nature’s muted nothingness, Flusser suggests that humans communicate by storing memories, externalized thoughts whose eventual transmission binds two or more people into a system of meaning. Only when an intersubjective system of communication like writing or speech is established between people does the purpose of our enduring commitment to communication become clear: we communicate in order “to become immortal within others” (2016, 31). Flusser’s playful positing of the ironic paradox inherent in the improbability of communication—that communication is unnatural to the human but it is also “so incredibly rich despite its limitations” (26)––enacts its own impossibility. In a representatively ironic sense, Flusser’s point is that all we are able to fully understand is our inability to understand fully.

As Flusser’s theory of communication can be viewed as his response to the twentieth-century’s shifting technical-medial milieu, his ideas about communication and technics eventually led him to conclude that “the original intention of producing the apparatus, namely, to serve the interests of freedom, has turned on itself…In a way, the terms human and apparatus are reversed, and human beings operate as a function of the apparatus. A man gives an apparatus instructions that the apparatus has instructed him to give” (2011,73).[1] Flusser’s skeptical perspective toward the alleged affordances of human mastery over technology is most assuredly not the view that Apple or Google would prefer you harbor (not-so-secretly). Any cursory glance at Wired or the technology blog at Insider Higher Ed, to pick two long-hanging examples, would yield a radically different perspective than the one Flusser puts forth in his work. In fact, Flusser writes, “objects meant to be media may obstruct communication” (2016, 45). If media objects like the technical apparatuses of today actually obstruct communication, then why are we so often led to believe that they facilitate it? And to shift registers just slightly, if everything is said to be an object of some kind—even technical apparatuses––then cannot one be permitted to claim daily communion with all kinds of objects? What happens when an object—and an object as obsolete as a book, no less—speaks to us? Will we still heed its call?

***

Speaking in its expanded capacity as neither narrator nor focalized character, the book as literary object addresses us in a direct and antagonistic fashion in the opening line to Joshua Cohen’s 2015 novel Book of Numbers. “If you’re reading this on a screen, fuck off. I’ll only talk if I’m gripped with both hands” (5), the book-object warns. As Cohen’s narrative tells the story of a struggling writer named Joshua Cohen (whose backstory corresponds mostly to the historical-biographical author Joshua Cohen) who is contracted to ghostwrite the memoir of another Joshua Cohen (who is the CEO of a massive Google-type company named Tetration), the novel’s middle section provides an “unedited” transcript of the conversation between the two Cohens in which the CEO recounts his upbringing and tremendous business success in and around the Bay Area from the late 1970s up to 2013 of the narrative’s present. The novel’s Silicon Valley setting, nominal and characterological doubling, and structural narrative coupling of the two Cohens’ lives makes it all but impossible to distinguish the personal histories of Cohen-the-CEO and Cohen-the-narrator from the cultural history of the development of personal computing and networked information technologies. The history of one Joshua Cohen––or all Joshua Cohens––is indistinguishable from the history of intrusive computational/digital media. “I had access to stuff I shouldn’t have had access to, but then Principal shouldn’t have had such access to me—cameras, mics,” Cohen-the-narrator laments. In other words, as Cohen-the-narrator ghostwrites another Cohen’s memoir within the context of the broad history of personal computing and the emergence of algorithmic governance and surveillance, the novel invites us to consider how the history of an individual––or every individual, it does not really matter––is also nothing more or anything less than the surveilled history of its data usage, which is always written by someone or something else, the ever-present Not-Me (who just might have the same name as me). The Self is nothing but a networked repository of information to be mined in the future.

While the novel’s opening line addresses its hypothetical reader directly, its relatively benign warning fixes reader and text in a relation of rancor. The object speaks![2] And yet tech-savvy twenty-first century readers are not the only ones who seem to be fed up with books; books too are fed up with us, and perhaps rightly so. In an age when objects are said to speak vibrantly and withdraw infinitely; processes like human cognition are considered to be operative in complex technical-computational systems; and when the only excuse to preserve the category of “subjective experience” we are able to muster is that it affords us the ability “to grasp how networks technically distribute and disperse agency,” it would seem at first glance that the second-person addressee of the novel’s opening line would intuitively have to be a reading, thinking subject.[3] Yet this is the very same reading subject who has been urged by Cohen’s novel to politely “fuck off” if he or she has chosen to read the text on a screen. And though the text does not completely dismiss its readers who still prefer “paper of pulp, covers of board and cloth” (5), a slight change of preposition in its title points exactly to what the book fears most of all: Book as Numbers. The book-object speaks, but only to offer an ominous admonition: neither the book nor its readers ought to be reducible to computable numbers.

The transduction of literary language into digital bits eliminates the need for a phenomenological, reading subject, and it suggests too that literature––or even just language in a general sense––and humans in particular are ontologically reducible to data objects that can be “read” and subsequently “interpreted” by computational algorithms. As Cohen’s novel collapses the distinction between author, narrator, character, and medium, its narrator observes that “the only record of my one life would be this record of another’s” (9). But in this instance, the record of one’s (or another’s) life is merely the history of how personal computational technologies have effaced the phenomenological subject. How have we arrived at the theoretically permissible premise that “People matter, but they don’t occupy a privileged subject position distinct from everything else in the world” (Huehls 20)? How might the “turn toward ontology” in theory/philosophy be viewed as contributing to our present condition?

* **

Mark Jarzombek’s Digital Stockholm Syndrome in the Post-Ontological Age (2016) provides a brief, yet stylistically ironic and incisive interrogation into how recent iterations of post- or inhumanist theory have found a strange bedfellow in the rhetorical boosterism that accompanies the alleged affordances of digital technologies and big data. Despite the differences between these two seemingly unrelated discourses, they both share a particularly critical or diminished conception of the anthro- in “anthropocentrism” that borrows liberally from the postulates of the “ontological turn” in theory/philosophy (Rosenberg n.p.). While the parallels between these discourses are not made explicit in Jarzombek’s book, Digital Stockholm Syndrome asks us to consider how a shared commitment to an ontologically diminished view of “the human” that galvanizes both technological determinism’s anti-humanism and post- or inhumanist theory has found its common expression in recent philosophies of ontology. In other words, the problem Digital Stockholm Syndrome takes up is this: what kind of theory of ontology, Being, and to a lesser extent, subjectivity, appeals equally to contemporary philosophers and Silicon Valley tech-gurus? Jarzombek gestures toward such an inquiry early on: “What is this new ontology?” he asks, and “What were the historical situations that produced it? And how do we adjust to the realities of the new Self?” (x).

A curious set of related philosophical commitments united by their efforts to “de-center” and occasionally even eject “anthropocentrism” from the critical conversation constitute some of the realities swirling around Jarzombek’s “new Self.”[4] Digital Stockholm Syndrome provocatively locates the conceptual legibility of these philosophical realities squarely within an explicitly algorithmic-computational historical milieu. By inviting such a comparison, Jarzombek’s book encourages us to contemplate how contemporary ontological thought might mediate our understanding of the historical and philosophical parallels that bind the tradition of in humanist philosophical thinking and the rhetoric of twenty-first century digital media.[5]

In much the same way that Alexander Galloway has argued for a conceptual confluence that exceeds the contingencies of coincidence between “the structure of ontological systems and the structure of the most highly evolved technologies of post-Fordist capitalism” (347), Digital Stockholm Syndrome argues similarly that today’s world is “designed from the micro/molecular level to fuse the algorithmic with the ontological” (italics in original, x).[6] We now understand Being as the informatic/algorithmic byproduct of what ubiquitous computational technologies have gathered and subsequently fed back to us. Our personal histories––or simply the records of our data use (and its subsequent use of us)––comprise what Jarzombek calls our “ontic exhaust…or what data experts call our data exhaust…[which] is meticulously scrutinized, packaged, formatted, processed, sold, and resold to come back to us in the form of entertainment, social media, apps, health insurance, clickbait, data contracts, and the like” (x).

The empty second-person pronoun is placed on equal ontological footing with, and perhaps even defined by, its credit score, medical records, 4G data usage, Facebook likes, and threefold of its Tweets. “The purpose of these ‘devices,’” Jarzombek writes, “is to produce, magnify, and expose our ontic exhaust” (25). We give our ontic exhaust away for free every time we log into Facebook because it, in return, feeds back to us the only sense of “self” we are able to identify as “me.”[7] If “who we are cannot be traced from the human side of the equation, much less than the analytic side.‘I’ am untraceable” (31), then why do techno-determinists and contemporary oracles of ontology operate otherwise? What accounts for their shared commitment to formalizing ontology? Why must the Self be tracked and accounted for like a map or a ledger?

As this “new Self,” which Jarzombek calls the “Being-Global” (2), travels around the world and checks its bank statement in Paris or tags a photo of a Facebook friend in Berlin while sitting in a cafe in Amsterdam, it leaks ontic exhaust everywhere it goes. While the hoovering up of ontic exhaust by GPS and commercial satellites “make[s] us global,” it also inadvertently redefines Being as a question of “positioning/depositioning” (1). For Jarzombek, the question of today’s ontology is not so much a matter of asking “what exists?” but of asking “where is it and how can it be found?” Instead of the human who attempts to locate and understand Being, now Being finds us, but only as long as we allow ourselves to be located.

Today’s ontological thinking, Jarzombek points out, is not really interested in asking questions about Being––it is too “anthropocentric.”[8] Ontology in the twenty-first century attempts to locate Being by gathering data, keeping track, tracking changes, taking inventory, making lists, listing litanies, crunching the numbers, and searching the database. “Can I search for it on Google?” is now the most important question for ontological thought in the twenty-first century.

Ontological thinking––which today means ontological accounting, or finding ways to account for the ontologically actuarial––is today’s philosophical equivalent to a best practices for data management, except there is no difference between one’s data and one’s Self. Nonetheless, any ontological difference that might have once stubbornly separated you from data about you no longer applies. Digital Stockholm Syndrome identifies this shift with the formulation: “From ontology to trackology” (71).[9] The philosophical shift that has allowed data about the Self to become the ontological equivalent to the Self emerges out of what Jarzombek calls an “animated ontology.”

In this “animated ontology,” subject position and object position are indistinguishable…The entire system of humanity is microprocessed through the grid of sequestered empiricism” (31, 29). Jarzombek is careful to distinguish his “animated ontology” from the recently rebooted romanticisms which merely turn their objects into vibrant subjects. He notes that “the irony is that whereas the subject (the ‘I’) remains relatively stable in its ability to self-affirm (the lingering by-product of the psychologizing of the modern Self), objectivity (as in the social sciences) collapses into the illusions produced by the global cyclone of the informatic industry” (28).”[10] By devising tricky new ways to flatten ontology (all of which are made via po-faced linguistic fiat), “the human and its (dis/re-)embodied computational signifiers are on equal footing”(32). I do not define my data, but my data define me.

***

Digital Stockholm Syndrome asserts that what exists in today’s ontological systems––systems both philosophical and computational––is what can be tracked and stored as data. Jarzombek sums up our situation with another pithy formulation: “algorithmic modeling + global positioning + human scaling +computational speed=data geopolitics” (12). While the universalization of tracking technologies defines the “global” in Jarzombek’s Being-Global, it also provides us with another way to understand the humanities’ enthusiasm for GIS and other digital mapping platforms as institutional-disciplinary expressions of a “bio-chemo-techno-spiritual-corporate environment that feeds the Human its sense-of-Self” (5).

One wonders if the incessant cultural and political reminders regarding the humanities’ waning relevance have moved humanists to reconsider the very basic intellectual terms of their broad disciplinary pursuits. How come it is humanities scholars who are in some cases most visibly leading the charge to overturn many decades of humanist thought? Has the internalization of this depleted conception of the human reshaped the basic premises of humanities scholarship, Digital Stockholm Syndrome wonders? What would it even mean to pursue a “humanities” purged of “the human?” And is it fair to wonder if this impoverished image of humanity has trickled down into the formation of new (sub)disciplines?”[11]

In a late chapter titled “Onto-Paranoia,” Jarzombek finally arrives at a working definition of Digital Stockholm Syndrome: data visualization. For Jarzombek, data-visualization “has been devised by the architects of the digital world” to ease the existential torture—or “onto-torture”—that is produced by Security Threats (59). Security threats are threatening because they remind us that “security is there to obscure the fact that whole purpose is to produce insecurity” (59). When a system fails, or when a problem occurs, we need to be conscious of the fact that the system has not really failed; “it means that the system is working” (61).[12] The Social, the Other, the Not-Me—these are all variations of the same security threat, which is just another way of defining “indeterminacy” (66). So if everything is working the way it should, we rarely consider the full implications of indeterminacy—both technical and philosophical—because to do so might make us paranoid, or worse: we would have to recognize ourselves as (in)human subjects.

Data-visualizations, however, provide a soothing salve which we can (self-)apply in order to ease the pain of our “onto-torture.” Visualizing data and creating maps of our data use provide us with a useful and also pleasurable tool with which we locate ourselves in the era of “post-ontology.”[13] “We experiment with and develop data visualization and collection tools that allow us to highlight urban phenomena. Our methods borrow from the traditions of science and design by using spatial analytics to expose patterns and communicating those results, through design, to new audiences,” we are told by one data-visualization project (http://civicdatadesignlab.org/). As we affirm our existence every time we travel around the globe and self-map our location, we silently make our geo-data available for those who care to sift through it and turn it into art or profit.

“It is a paradox that our self-aestheticizing performance as subjects…feeds into our ever more precise (self-)identification as knowable and predictable (in)human-digital objects,” Jarzombek writes. Yet we ought not to spend too much time contemplating the historical and philosophical complexities that have helped create this paradoxical situation. Perhaps it is best we do not reach the conclusion that mapping the Self as an object on digital platforms increases the creeping unease that arises from the realization that we are mappable, hackable, predictable, digital objects––that our data are us. We could, instead, celebrate how our data (which we are and which is us) is helping to change the world. “’Big data’ will not change the world unless it is collected and synthesized into tools that have a public benefit,” the same data visualization project announces on its website’s homepage.

While it is true that I may be a little paranoid, I have finally rested easy after having read Digital Stockholm Syndrome because I now know that my data/I are going to good use.[14] Like me, maybe you find comfort in knowing that your existence is nothing more than a few pixels in someone else’s data visualization.

_____

Michael Miller is a doctoral candidate in the Department of English at Rice University. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in symplokē and the Journal of Film and Video.

_____

Notes

[1] I am reminded of a similar argument advanced by Tung-Hui Hu in his A Prehistory of the Cloud (2016). Encapsulating Flusser’s spirit of healthy skepticism toward technical apparatuses, the situation that both Flusser and Hu fear is one in which “the technology has produced the means of its own interpretation” (xixx).

[2] It is not my aim to wade explicitly into discussions regarding “object-oriented ontology” or other related philosophical developments. For the purposes of this essay, however, Andrew Cole’s critique of OOO as a “new occasionalism” will be useful. “’New occasionalism,’” Cole writes, “is the idea that when we speak of things, we put them into contact with one another and ourselves” (112). In other words, the speaking of objects makes them objectively real, though this is only possible when everything is considered to be an object. The question, though, is not about what is or is not an object, but is rather what it means to be. For related arguments regarding the relation between OOO/speculative realism/new materialism and mysticism, see Sheldon (2016), Altieri (2016), Wolfendale (2014), O’Gorman (2013), and to a lesser extent Colebrook (2013).

[3] For the full set of references here, see Bennett (2010), Hayles (2014 and 2016), and Hansen (2015).

[4] While I cede that no thinker of “post-humanism” worth her philosophical salt would admit the possibility or even desirability of purging the sins of “correlationism” from critical thought all together, I cannot help but view such occasional posturing with a skeptical eye. For example, I find convincing Barbara Herrnstein-Smith’s recent essay “Scientizing the Humanities: Shifts, Negotiations, Collisions,” in which she compares the drive in contemporary critical theory to displace “the human” from humanistic inquiry to the impossible and equally incomprehensible task of overcoming the “‘astro’-centrism of astronomy or the biocentrism of biology” (359).

[5] In “Modest Proposal for the Inhuman,” Julian Murphet identifies four interrelated strands of post- or inhumanist thought that combine a kind of metaphysical speculation with a full-blown demolition of traditional ontology’s conceptual foundations. They are: “(1) cosmic nihilism, (2) molecular bio-plasticity, (3) technical accelerationism, and (4) animality. These sometimes overlapping trends are severally engaged in the mortification of humankind’s stubborn pretensions to mastery over the domain of the intelligible and the knowable in an era of sentient machines, routine genetic modification, looming ecological disaster, and irrefutable evidence that we share 99 percent of our biological information with chimpanzees” (653).

[6] The full quotation from Galloway’s essay reads: “Why, within the current renaissance of research in continental philosophy, is there a coincidence between the structure of ontological systems and the structure of the most highly evolved technologies of post-Fordist capitalism? [….] Why, in short, is there a coincidence between today’s ontologies and the software of big business?” (347). Digital Stockholm Syndrome begins by accepting Galloway’s provocations as descriptive instead of speculative. We do not necessarily wonder in 2017 if “there is a coincidence between today’s ontologies and the software of big business”; we now wonder instead how such a confluence came to be.

[7] Wendy Hui Kyun Chun makes a similar point in her 2016 monograph Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media. She writes, “If users now ‘curate’ their lives, it is because their bodies have become archives” (x-xi). While there is not ample space here to discuss the full theoretical implications of her book, Chun’s discussion of the inherently gendered dimension to confession, self-curation as self-exposition, and online privacy as something that only the unexposed deserve (hence the need for preemptive confession and self-exposition on the internet) in digital/social media networks is tremendously relevant to Jarzombek’s Digital Stockholm Syndrome, as both texts consider the Self as a set of mutable and “marketable/governable/hackable categories” (Jarzombek 26) that are collected without our knowledge and subsequently fed back to the data/media user in the form of its own packaged and unique identity. For recent similar variations of this argument, see Simanowski (2017) and McNeill (2012).

I also think Chun’s book offers a helpful tool for thinking through recent confessional memoirs or instances of “auto-theory” (fictionalized or not) like Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts (2015), Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be (2010), Marie Calloway’s what purpose did i serve in your life (2013), and perhaps to a lesser degree Tao Lin’s Richard Yates (2010), Taipei (2013), Natasha Stagg’s Surveys, and Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station (2011) and 10:04 (2014). The extent to which these texts’ varied formal-aesthetic techniques can be said to be motivated by political aims is very much up for debate, but nonetheless, I think it is fair to say that many of them revel in the reveal. That is to say, via confession or self-exposition, many of these novels enact the allegedly performative subversion of political power by documenting their protagonists’ and/or narrators’ certain social/political acts of transgression. Chun notes, however, that this strategy of self-revealing performs “resistance as a form of showing off and scandalizing, which thrives off moral outrage. This resistance also mimics power by out-spying, monitoring, watching, and bringing to light, that is, doxing” (151). The term “autotheory,” which was has been applied to Nelson’s The Argonauts in particular, takes on a very different meaning in this context. “Autotheory” can be considered as a theory of the self, or a self-theorization, or perhaps even the idea that personal experience is itself a kind of theory might apply here, too. I wonder, though, how its meaning would change if the prefix “auto” was understood within a media-theoretical framework not as “self” but as “automation.” “Autotheory” becomes, then, an automatization of theory or theoretical thinking, but also a theoretical automatization; or more to the point: what if “autotheory” describes instead a theorization of the Self or experience wherein “the self” is only legible as the product of automated computational-algorithmic processes?

[8] Echoing the critiques of “correlationism” or “anthropocentrism” or what have you, Jarzombek declares that “The age of anthrocentrism is over” (32).

[9] Whatever notion of (self)identity the Self might find to be most palatable today, Jarzombek argues, is inevitably mediated via global satellites. “The intermediaries are the satellites hovering above the planet. They are what make us global–what make me global” (1), and as such, they represent the “civilianization” of military technologies (4). What I am trying to suggest is that the concepts and categories of self-identity we work with today are derived from the informatic feedback we receive from long-standing military technologies.

[10] Here Jarzombek seems to be suggesting that the “object” in the “objectivity” of “the social sciences” has been carelessly conflated with the “object” in “object-oriented” philosophy. The prioritization of all things “objective” in both philosophy and science has inadvertently produced this semantic and conceptual slippage. Data objects about the Self exist, and thus by existing, they determine what is objective about the Self. In this new formulation, what is objective about the Self or subject, in other words, is what can be verified as information about the self. In Indexing It All: The Subject in the Age of Documentation, Information, and Data (2014), Ronald Day argues that these global tracking technologies supplant traditional ontology’s “ideas or concepts of our human manner of being” and have in the process “subsume[d] and subvert[ed] the former roles of personal judgment and critique in personal and social beings and politics” (1). While such technologies might be said to obliterate “traditional” notions of subjectivity, judgment, and critique, Day demonstrates how this simultaneous feeding-forward and feeding back of data-about-the-Self represents the return of autoaffection, though in his formulation self-presence is defined as information or data-about-the-self whose authenticity is produced when it is fact-checked against a biographical database (3)—self-presence is a presencing of data-about-the-Self. This is all to say that the Self’s informational “aboutness”–its representation in and as data–comes to stand in for the Self’s identity, which can only be comprehended as “authentic” in its limited metaphysical capacity as a general informatic or documented “aboutness.”

[11] Flusser is again instructive on this point, albeit in his own idiosyncratic way. Drawing attention to the strange unnatural plurality in the term “humanities,” he writes, “The American term humanities appropriately describes the essence of these disciplines. It underscores that the human being is an unnatural animal” (2002, 3). The plurality of “humanities,” as opposed to the singular “humanity,” constitutes for Flusser a disciplinary admission that not only the category of “the human” is unnatural, but that the study of such an unnatural thing is itself unnatural, as well. I think it is also worth pointing out that in the context of Flusser’s observation, we might begin to situate the rise of “the supplemental humanities” as an attempt to redefine the value of a humanities education. The spatial humanities, the energy humanities, medical humanities, the digital humanities, etc.—it is not difficult to see how these disciplinary off-shoots consider themselves as supplements to whatever it is they think “the humanities” are up to; regardless, their institutional injection into traditional humanistic discourse will undoubtedly improve both(sub)disciplines, with the tacit acknowledgment being that the latter has just a little more to gain from the former in terms of skills, technical know-how, and data management. Many thanks to Aaron Jaffe for bringing this point to my attention.

[12] In his essay “Algorithmic Catastrophe—The Revenge of Contingency,” Yuk Hui notes that “the anticipation of catastrophe becomes a design principle” (125). Drawing from the work of Bernard Stiegler, Hui shows how the pharmacological dimension of “technics, which aims to overcome contingency, also generates accidents” (127). And so “as the anticipation of catastrophe becomes a design principle…it no longer plays the role it did with the laws of nature” (132). Simply put, by placing algorithmic catastrophe on par with a failure of reason qua the operations of mathematics, Hui demonstrates how “algorithms are open to contingency” only insofar as “contingency is equivalent to a causality, which can be logically and technically deduced” (136). To take Jarzombek’s example of the failing computer or what have you, while the blue screen of death might be understood to represent the faithful execution of its programmed commands, we should also keep in mind that the obverse of Jarzombek’s scenario would force us to come to grips with how the philosophical implications of the “shit happens” logic that underpins contingency-as-(absent) causality “accompanies and normalizes speculative aesthetics” (139).

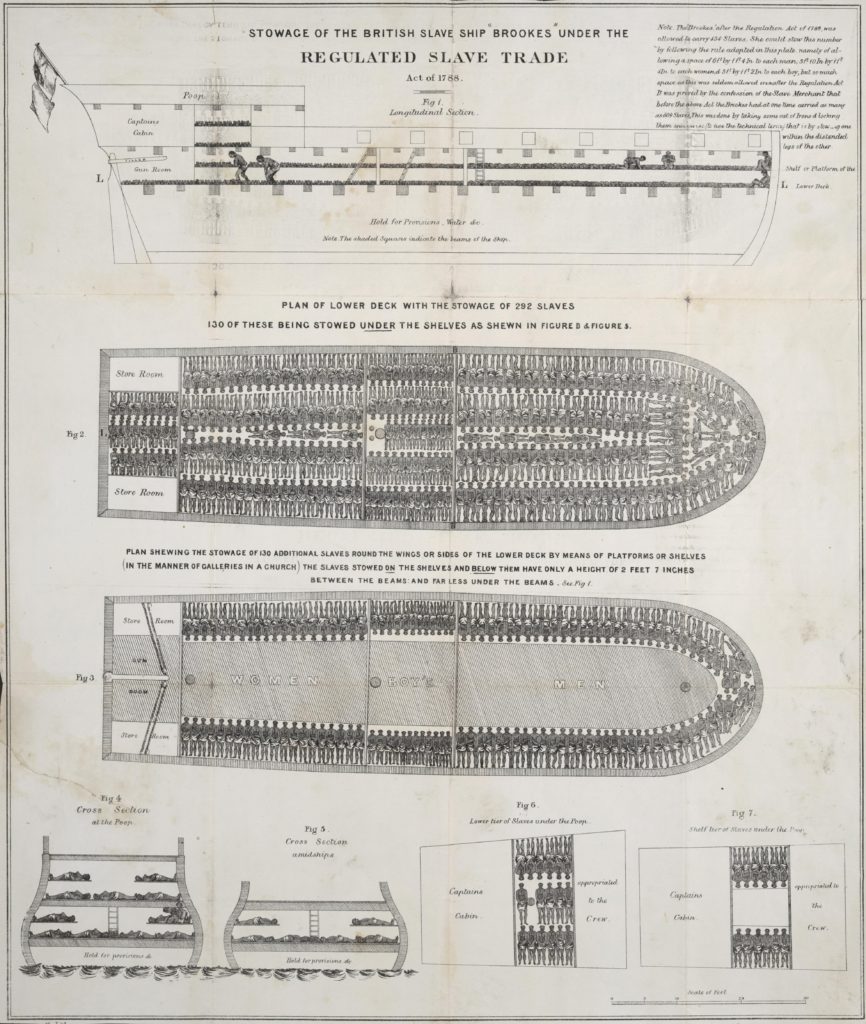

[13] I am reminded here of one of the six theses from the manifesto “What would a floating sheep map?,” jointly written by the Floating Sheep Collective, which is a cohort of geography professors. The fifth thesis reads: “Map or be mapped. But not everything can (or should) be mapped.” The Floating Sheep Collective raises in this section crucially important questions regarding ownership of data with regard to marginalized communities. Because it is not always clear when to map and when not to map, they decide that “with mapping squarely at the center of power struggles, perhaps it’s better that not everything be mapped.” If mapping technologies operate as ontological radars–the Self’s data points help point the Self towards its own ontological location in and as data—then it is fair to say that such operations are only philosophically coherent when they are understood to be framed within the parameters outlined by recent iterations of ontological thinking and its concomitant theoretical deflation of the rich conceptual make-up that constitutes the “the human.” You can map the human’s data points, but only insofar as you buy into the idea that points of data map the human. See http://manifesto.floatingsheep.org/.

[14] “Mind/paranoia: they are the same word!”(Jarzombek 71).

_____

Works Cited

- Adler, Renata. Speedboat. New York Review of Books Press, 1976.

- Altieri, Charles. “Are We Being Materialist Yet?” symplokē 24.1-2 (2016):241-57.

- Calloway, Marie. what purpose did i serve in your life. Tyrant Books, 2013.

- Chun, Wendy Hui Kyun. Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media. The MIT Press, 2016.

- Cohen, Joshua. Book of Numbers. Random House, 2015.

- Cole, Andrew. “The Call of Things: A Critique of Object-Oriented Ontologies.” minnesota review 80 (2013): 106-118.

- Colebrook, Claire. “Hypo-Hyper-Hapto-Neuro-Mysticism.” Parrhesia 18 (2013).

- Day, Ronald. Indexing It All: The Subject in the Age of Documentation, Information, and Data. The MIT Press, 2014.

- Floating Sheep Collective. “What would a floating sheep map?” http://manifesto.floatingsheep.org/.

- Flusser, Vilém. Into the Universe of Technical Images. Translated by Nancy Ann Roth. University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

- –––. The Surprising Phenomenon of Human Communication. 1975. Metaflux, 2016.

- –––. Writings, edited by Andreas Ströhl. Translated by Erik Eisel. University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

- Galloway, Alexander R. “The Poverty of Philosophy: Realism and Post-Fordism.” Critical Inquiry 39.2 (2013): 347-366.

- Hansen, Mark B.N. Feed Forward: On the Future of Twenty-First Century Media. Duke University Press, 2015.

- Hayles, N. Katherine. “Cognition Everywhere: The Rise of the Cognitive Nonconscious and the Costs of Consciousness.” New Literary History 45.2 (2014):199-220.

- –––. “The Cognitive Nonconscious: Enlarging the Mind of the Humanities.” Critical Inquiry 42 (Summer 2016): 783-808.

- Herrnstein-Smith, Barbara. “Scientizing the Humanities: Shifts, Collisions, Negotiations.” Common Knowledge 22.3 (2016):353-72.

- Heti, Sheila. How Should a Person Be? Picador, 2010.

- Hu, Tung-Hui. A Prehistory of the Cloud. The MIT Press, 2016.

- Huehls, Mitchum. After Critique: Twenty-First Century Fiction in a Neoliberal Age. Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Hui, Yuk. “Algorithmic Catastrophe–The Revenge of Contingency.” Parrhesia 23(2015): 122-43.

- Jarzombek, Mark. Digital Stockholm Syndrome in the Post-Ontological Age. University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

- Lin, Tao. Richard Yates. Melville House, 2010.

- –––. Taipei. Vintage, 2013.

- McNeill, Laurie. “There Is No ‘I’ in Network: Social Networking Sites and Posthuman Auto/Biography.” Biography 35.1 (2012): 65-82.

- Murphet, Julian. “A Modest Proposal for the Inhuman.” Modernism/Modernity 23.3(2016): 651-70.

- Nelson, Maggie. The Argonauts. Graywolf P, 2015.

- O’Gorman, Marcel. “Speculative Realism in Chains: A Love Story.” Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities 18.1 (2013): 31-43.

- Rosenberg, Jordana. “The Molecularization of Sexuality: On Some Primitivisms of the Present.” Theory and Event 17.2 (2014): n.p.

- Sheldon, Rebekah. “Dark Correlationism: Mysticism, Magic, and the New Realisms.” symplokē 24.1-2 (2016): 137-53.

- Simanowski, Roberto. “Instant Selves: Algorithmic Autobiographies on Social Network Sites.” New German Critique 44.1 (2017): 205-216.

- Stagg, Natasha. Surveys. Semiotext(e), 2016.

- Wolfendale, Peter. Object Oriented Philosophy: The Noumenon’s New Clothes. Urbanomic, 2014.