This text is published as part of a special b2o issue titled “Critique as Care”, edited by Norberto Gomez, Frankie Mastrangelo, Jonathan Nichols, and Paul Robertson, and published in honor of our b2o and b2 colleague and friend, the late David Golumbia.

Ravishing Regulations and Digital Bodies: Metabolizing #Metoo

Jeanette Vigliotti King

“It matters which stories tell stories, which concepts think concepts. Mathematically, visually, and narratively, it matters which figures figure figures, which systems systematize systems.” – Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene

In the late 2000s, David Golumbia claimed examining the rhetoric of computation allowed for an interrogation of “those aspects of institutional power aided through belief in the superior utility of computerization as a form of social and political organization” (2009: 3). Golumbia provides a compass for navigating the slippery ways in which computers and digital life continue to obscure harm. As Golumbia states, the rhetoric of computation always carries veneers of newness and radical breaks—social media spaces are know exceptions for striking poses of liberation, newness, and connection. Like David before me, I aim to understand the ways in which digital social networking sites can be read as texts with “cultural and historical contexts” (Golumbia 2009:2). In this essay, I read metabolism, zombies, and the hashtag as interconnected logics of digital circulation: a way which bodies and stories affectively move through digital space and are rendered legible on digital bodies. This framework is particularly helpful for reading the emergence, spread, and afterlife of #Metoo.

The October 2017 #Metoo[1] campaign spoke wounds to life, narrating a historical story of repressed violence (Geiseler 2019). #Metoo produced largely absented, shamed narratives of sexual assault survivors. The conventions for online participation and meaning making were strategically and tactically deployed to force marginalized, nondominant, and traumatic narrative into focus—causing these stories to metabolize and explicitly enter forums of knowledge production. As such, the digital wound named by #metoo told stories about normative health presentation and bodies on social media sites. I offer the concept zombie hunger to theorize more broadly how the unstable categories of consumer/consumed were levied during the October 2017 #Metoo multiplatform media event.

Zombies are potent metaphors, a cultural figure that can be mobilized to track what persists after a body has been designated as abject, abandoned, or made socially dead. Zombie hunger refers to a structural condition of unending need: a repetitive reaching toward recognition, repair, and justice that fails to be fully satisfied under platform capitalism. In other words

Zombie hunger accounts for the ways personal, uploaded social media information metabolizes with human and nonhuman others. In this sense, zombie hunger tracks how digital bodies become-with. Uploaded information is not passive, but an integral part of knowledge production in Facebook and Instagram. If uploaded information fits within certain criteria, the information circulates freely, touching many digital bodies, bringing them together. Metabolized data allows users to become-with human and nonhumans alike. (King 2025: 2)

Its affordances lie in naming how survivors’ stories circulate as both vital and emptied material which human and nonhuman platform actants metabolize, creating moments of rupture and visibility. Its limit is the zombie metaphor risks reinscribing dehumanization. Therefore, I find the zombie useful for foregrounding the structural hunger associated with social media platforms. As a mode of cultural critique, the figure of zombies describes viral, collective and grotesque consumption, giving name to the textual cannibalism that occurs within digital social media platforms. As a descriptive figure, zombies are helpful for naming ruptures in protocol. As in films and books, zombies spread by using existing networks of contact and proximity—planes, trains, malls—anywhere people gather, are seen, and see others. Zombies are not liberators, but like all monstrous figures, can reveal harm and warn against ways of being in the world. In this way, zombies offer a Golumbian critique: “we have to learn how to critique even that which helps us” (Golumbia 2009: 13). Read this way, the figure of the zombie is both critique and care practice: a critique of the logics of consumption in social media space which translates articulated trauma into data and a care practice for its insistence that what haunts, what returns, what stalks does so because it has not been tended to.

Zombies metabolize—a process that regulates which bodily functions happen. Metabolism, Hannah Landecker argues, is not autonomous but dependent on multiple actants which destabilize agential positions of life (as active) and death (as passive). Consequently, the fixed hierarchy of consumer and consumed cease to be stable markers defining a body. Metabolism offers language for the divergent ways temporality, life, and death manifest for digital life. Since zombies are never singular, but always part of a horde, the metaphor is useful to think with for the ways a collectivized metabolism operates. Zombies as a figure help think about ways in which traumatic narratives are spread compulsively, blurring distinctions between self/other, consumer/consumed, alive/dead, health/sick.

Hashtags, which are clickable links that organize and bind an uploader’s personal information to others on social media sites, can be thought of as metabolic in nature. The hashtag marked users, compelling others to witness and consume their narratives. Since regulation as a process leads to physiological change, #Metoo forced digital consumption through uncanny, repetitive exposure. Hashtags, like zombies, rely on collective meaning making, their power drawn from contact and hybridity.

#Metoo can be understood as a monstrous story of hunger, a tale of what one cannot speak alone. In the case of #Metoo, zombie hunger is enacted through: 1) the uploader self-reporting information; 2) the uploader selecting a hashtag; 3) the hashtagged post is algorithmically selected to join other user’s feeds; 4) other users consuming the hashtagged post on their feed; 5) other users clicking the hashtag; 6) other users becoming an uploader. This process mirrors the ways the mid-twentieth century zombie operates—through consumption, transmission, and integration. #Metoo narratives transformed as they circulated, shaping and being shaped by the digital social media bodies. #Metoo resists single authorship, instead forming an overwhelming mass of testimony.

The archive of #Metoo represents metabolized stories, kept alive through repetition and reproduction of the dominant social values of imagined communities. Paying attention to metabolized stories, I provide a close reading of October 2017 #Metoo to interrogate how repetition in digital spaces is operationalized to reveal normative practices and procedures. Which and whose stories are digestible? And why and how?

I examine infrastructures that successfully metabolized certain textual and imagistic #Metoo testimonies and how these regulated what other testimonies were marked in poor taste, perverse, or unpalatable. I close read texts in the public domain—newspaper articles about #Metoo, the viral media event in 2017—and the structural nature of the Facebook profile picture. Finally, I read and analyze artist and graphic designer @witchoria (Victoria Seimer)’s #Metoo image that circulated in the initial days of #Metoo to show how #Metoo offered a tactical, temporary disruption in how social media users collectively engaged with systemic sexual violence.

Going Viral: #Metoo 2017

In what follows, I will contextualize the 2017 #Metoo media event to demonstrated how metabolic and monstrous frameworks manifest within these narratives. In October 2017, actress Alyssa Milano tweeted “Suggested by a friend: If all the women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote ‘Me Too” as a status, we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem. If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet.”[2] Alyssa Milano’s tweet was initially considered the origin point for this particular media event, but activist Black feminist activist Tarana Burke had already created the campaign a decade earlier and has run programming to support survivors of sexual trauma (Vagianos 2017). Celebrities and non-celebrities alike added their voices on Twitter, and soon the hashtag #Metoo was trending. #Metoo made familiar platform conventions—like the live feed and the hashtag—a site of zombie- hording and hunger. #Metoo exposed the ways in which certain bodies – those that are disproportionately women, transwomen, and women of color—experience violence when they were figured as objects, fleshed commodities.

According to CBS News Report from October 17, 2017, 12 million posts featuring the hashtag “me too” flooded Facebook (CBS 2017). Although this was not the first—or last—viral hashtag campaign about a social and political issue, #Metoo affords legible conversations about the yoked nature of the digital and physical body and how an appetite to consume content can be used to upend the normative operations of social networking spaces. Through the seemingly mundane #Metoo, this translated trauma effectively organized multiple organic and inorganic entities, human and nonhuman actants.

As more users added their voices to #Metoo, zombie hunger became a powerful, partially disruptive force. #Metoo participants used the conventions of the platform—of the pleasures of being seen and the pleasures of being consumed— to call attention to narratives not normally deemed polite or sayable. The repeated presence of #Metoo caused these stories to metabolize. In the specific case of #Metoo, the hashtag itself acts through this understanding of metabolism. The digital body of women who posted now bore a mark and thereby helped constitute what users, other users, and nonhuman actants were forced to “see” and “devour” while engaging with their live feed. Paraphrasing Hannah Landecker, the #Metoo status update is some of the “stuff out of which bodies are made.”(Landecker 2013: 4) Since regulation as a process leads to a “physiological change,” then #Metoo forces consumption through banal tactics that are rendered unfamiliar and uncanny (Landecker 2013 : 4).

I focus on hashtags as a mechanism of self-production and zombie hunger because hashtags have an agential capacity to shape and be shaped by existing and emergent bodies of knowledge. Zombie hunger in the form of agential hashtags operates within the framework of testimony.[3] Gilmore explains:

Testimony crosses the boundary between life and death, but also it tarries at the border and inhabits it as an extracorporeal entity. The testimonial body is both a surrogate for those who cannot testify and possess a life of its own. It persists across jurisdictions and can travel the globe. Its future is defined by its capacity to communicate about the past. It exceeds the bodies of the dead, but it carries their voice where it cannot go. Testimony constantly traverses the boundaries of the living and the dead and it derives its affective charge from its disembodied and authentic location. Testimony is haunted: by the dead to whom it bears witness, as well as the living who offer it and hear it. It carries histories of the past that are difficult to narrate, and it makes a claim on the present about current situations. (Gilmore 2017: 75).

#Metoo functioned as a kind of testimony as an “event and practice” which exists in spaces like autobiographies, memoirs, and digital social networks. When #Metoo was operationalized, the linked nature of the hashtag sent stories of sexual assault and violence skittering across the internet, infecting and replicating on Facebook, Reddit, Instagram taking over the live feeds of users. Every post with the hashtag carried a “disembodied” and “haunted” narrative through repetition in the testimonial network of multiple social media platforms.

Haunting seems to share a lot in common with hashtags: they are both patterns, repetitions, frequencies Haunted time is inherently an affective, nonmetric one. As Avery Gordon describes, haunting “alters the experience of being in time,” relies on repetition, and marks the re-emergence of social violence, disrupting stable notions of progress (Gordon 1997: xvi). With #Metoo, the familiar body presented a haunted and temporally displaced trauma for consumption that forced its consumers to look at absented, invisible wounds. The narrative form of hashtags draws power from repetition and dissemination. In this way, repetition combined with the desire to look becomes metabolic because meaning and power are not autonomously generated, but generated and regulated in concert with algorithms, hashtags, and other users.

By adhering to the temporal logics of repetition, every affective engagement in social media –reactions, shares, hashtags–amplifies the larger message. According to Nicole Brodeur (2017), a columnist for The Seattle Times who also participated in #Metoo, if “the Me toos’ keep coming. Some from transgender women, some from gender nonconforming people…. we’ve not just opened a dialogue here. We’ve exposed the abuse of power and shown there is strength in numbers.” Brodeur (2017) explains how she watched “drips” of #Metoo until there was a “deluge.” The repetition, the connection, or as she says, “strength in numbers,” demonstrates the capacity of what narratives are going to be digested, which ones will force their way into public discourse (Brodeur 2017).

The case of #Metoo shows how hashtags are nonhuman others, co-producing both desires and hunger. Hashtags have the capacity to work alongside humans to flip normative scripts and shape reality and knowledge systems, allowing for communities to form and transform understandings by forcing consumption through the logics of the live feed. Like hashtags, the zombie’s integrity and meaning-making capacity is dependent on contact with others, by the act of consumption as a moment of transformative power.

Similarly, in postapocalyptic literature, it is the presence of the zombie that is more urgent, more important than understanding who that zombie is or was; in the #Metoo movement, the name of the participant is not nearly as urgent as the admission itself: “me, too.” When the hashtag flooded feeds, an overwhelming mass of trauma images became accessible merely through acts of repetition. But the integrity of #Metoo, like other hashtags, is dependent upon its contact with other matters. A singular hashtag, unattached to other signifiers, has diminished meaning, reduced capacity to create (digital) physiological change to the linked social body. Zombies, too, are seldom singular; they gain full recognition in a zombie horde in which individual distinction is not the defining feature. Zombies gain meaning in relationship to each other, read against orderly, healthy bodies free from disease. Zombies are an act of translation, moving between life and death, consumer and consumed. Like the pronoun “you,” zombies occupy a space of general and individual distinction.[4]

Iterative Practices: Metabolizing Life-Writing and Trauma

Sexual assault, like all trauma, exists at the space where language bucks, becomes undomesticated, caught between an embodied moment then and an embodied moment now. #Metoo offered a tactical, temporary disruption in the how social media users collectively engage with systemic sexual violence. In #Metoo, users and hashtags were webbed, related, co-authors in a story that extended beyond the body of one individual. Read retroactively, #Metoo is a monstrous story of hunger, a tale of what one cannot speak alone. Instead, #Metoo now signifies through volume, each story tacked on, made alive—hunting and haunting—through the nonhuman actor of a hashtag, growing more powerful through what doesn’t have to leave the lips of the user. Haunting is fraught with repetition, what demands to be re-seen again and again. Repetition is also a temporal displacement, a scene which materializes through various structures brushing up against each other. When applied to digital spaces, haunting’s affective uncanny persistence is rendered visible, particularly with recurrent encounters with traumatic events slicing into scrolling sessions via algorithmic circulation. In a digital social media site, users are likely to encounter content in shuffled time and order, rather than a strict linear fashion.

Life-writing in digital spaces expands opportunities and forms to report, share, and connect self-representation stories; like the haunted bodily form of the zombie, it constantly weaves between interiority and exteriority. Rippl et al. (2013: 7) prefer the term “life-writing’ over autobiography…[because] the latter tends to privilege certain ways of writing about the self [and] conform to the Western Enlightenment narrative of the autonomous self determined (and at least implicitly male) individual which usually favors narrative regularity.” Life-writing is a way to center those narratives “by women, people of color, post-colonial subjects, and other historically marginalized groups, whose stories of violence and oppression are often rendered in non-linear and fragmented forms.” (Rippl et al 2013: 5). Since digital narratives rely on indexical access (rather than linear pagination), the digital temporal space of haunting provides the necessary language and strategies to think-with the lives and experiences of marginalized others.

Thinking about the processes which enable #Metoo as life-writing focuses on which bodies, even while articulating collectivized trauma, are still subjected to systemic and structural harm. Operating from a feminist philosophical position of strong objectivity, classing #Metoo as a life-writing names the co-narrators (human and nonhuman alike) as historically and socially positioned, constructed at-once through available technologies, languages, and forms.[5] Trauma tests the limit of self-representation–it is extremely difficult to verbalize trauma. This testing necessitates a reconceptualization of the genres of self-representation that adhere to “legalistic definitions of the truth, sharply distinguish between the private and the public as well as the individual and the collective and presuppose a sovereign self as the teller of the tale” (Gilmore 2017: 7). #Metoo is haunted by this systemic violence in which a sovereign self is not the narrator. Corporeal experiences are given to digital bodies, formed both through the chain of production for the digital device, and the network of nonhuman others within the social media platform itself. #Metoo is a co-production whose potency and failings are deeply related to form or how the life-stories moved in a zombie-like horde.

Complicating Picture Perfect Health

Social media platforms offer a mirage of freedom. While users are free to upload their own images and contribute text, they must do so within strict boundaries. These platforms, though modifiable, follow an orderly format in which only images of certain sizes can be selected and uploaded. For instance, an uploader on Facebook has a hierarchy on their profile: an anchoring profile image, a banner image, a bolded name, and a wall where posts produced by the uploader and other users are visible. Every post follows a particular visual hierarchy: the profile picture in miniature, the uploader’s name, the content of the post (which includes things like a video or image uniformly formatted in a neat box) with text and the ability to incorporate hyperlinks in the form of hashtags or social tags to other profiles.

There is no variety, despite the platform’s insistence on wanting the uploader to express “What’s on your mind?” For uploaders, the question “what is on your mind?” can only be addressed in the same uniform way. The ability to choose what to upload obscures the ways in which the platform itself, to use Golumbia’s work, creates a “central perspective; whatever the diversity of the input tory, the output is unified, hierarchized, striated, authoritative” (2009: 208).

There are also unwritten social conventions governing the construction of digital profiles—only particular kinds of images and life events, those usually associated with positive experiences, are generally circulated for public consumption (Calderia et al. 2020). Lauren Berlant explains, “Health itself can then be seen as a side effect of successful normativity, and people’s desires and fantasies are solicited to line up with that pleasant condition” (Berlant 2007: 765). Berlant’s assessment is readily extended to Facebook and Instagram. Bodies on these sites are positioned as healthy through a careful absenting of trauma and health woes. This adherence to “unification haunts” every post (Golumbia 2009: 208).These infrastructural practices of small digital repetitions such as uploading, reacting, sharing, and hashtagging uphold projects of normativity and reify the clean, upwardly mobile, white, able-bodied liberal subject.[6] Through such infrastructurally-encouraged repetitions, social norms and structural harm from “offline” continue to metabolize experiences “online.”[7]

Zombie hunger adheres to logics of repetition: #Metoo’s power depends on the collapse of consumer/consumed, forcing users scrolling on “their” feed to consume abject experiences that survivors have been taught to repress and whose narratives have been denied life in many institutional spaces. The violence to the body returns from the dead as a hungry hunter. Every move towards eating is repeated not only by an “individual” participant but amplified by the horde’s consumption rhyt as well. When users post comments on Facebook live feeds, a smaller image of the profile picture is to the left to the textual information—whether that is a link, another photograph, a few sentences, a life event, etc. In this way, the photograph and status update form a new photographic experience—the inclusion of the linguistic message that is inseparable from the image proper (Barthes 1977). The profile picture serves two primary purposes: to identify and authenticate the user. The profile picture becomes a digital handshake, carrying a user’s identity in the selected image. Many profile pictures are headshots, or artistic spins on headshots.

The Facebook profile picture inherits from portraiture producing healthy bodies for circulation. Tanya Sheehan explains the nineteenth century practice still permeates contemporary relationships with digital photographs as people “seek to create ‘healthy’ public images…that reproduce narrowly defined ideas about what it means to belong to an ‘American’ social group” (2011: 144). Facebook’s embedded photo tools focus primarily on brightening and lightening, while other non-native applications like Snapseed allow users to digitally enhance the body by removing blemishes, freckles, pounds–procedures and operations to make a digital body reproduce normative health which is always already positioned as white, heteronormative, and able-bodied. These apps, within and outside of Facebook, “generally ‘balance skin pigmentation idealize ‘pure’ whiteness as the desired norm” (Sheehan 2011: 144). Sheehan notes both “physical ‘excess’ and aging” are traits associated with “the lower class” whose lives are valued differently, particularly when class intersects with the vectors of race and gender. Although whitening practices are not the heart of my analysis, it is imperative to understand that the mechanisms for disseminating information reproduce normative health practices. Illness is absented and mitigated through healing tools, camera angles, and social conventions of reporting certain kinds of information.

Unification and repetition are mechanisms of zombie hunger for #Metoo. During the media event, the live feed of many users’ Facebooks were flooded with a jarring juxtaposition: a profile picture (likely in line with normative conventions) and the textual testimony of sexual assault or violence. This same structure which transmits fantasies of frictionless life was used to make one story viral, a story that testifies abuses to the physical body.

The presence of #Metoo next to a profile picture disrupts the healthy body through a haunted temporality. #Metoo haunts and intervenes norms of the profile picture and status box[8]. The contingent nature of the photograph is reinscribed with admissions of sexual assault and violence, altering the unwritten conventions of sharing only positive events and news associated with capitalist and white values of success (Wells et al. 2021). Instead, users scrolling through their Facebook live feeds are met with bodies and cannot help but taste.

Often, sexual assault and sexual trauma are invisible wounds that afflict 1 in 3 women and 1 and 6 men.[9] However, that trauma is not absented from the survivor’s experiences. With the inclusion of #Metoo beside the profile picture, each participating user generated a consuming horde, affecting and infecting other users. A 2019 study found that #Metoo did impact public awareness–there was an increase of google searches for the following keywords: sexual assault, sexual abuse, sexual harassment, and rape (Kaufman et al. 2021). Users were spurned, at the very least, to seek additional information about a health issue that disproportionally affects women and in which women of color, women with disabilities, women in low socioeconomic classes, and trans women are overrepresented. Kaufman et al (2021) explained:

The National Sexual Assault Conference held in August 2018 is one example of how the hashtag has been turned into action. The conference’s opening plenary featured Tarana Burke talking about where the #Metoo movement needs to go next (National Sexual Violence Resource Center, 2018; North, 2018). The #HowIWillChange follow-up movement is another example of hashtag activism resulting in clear ways to change behavior, although whether social media users actually engage in these promised behaviors is unknown. While a hashtag seems simplistic, and the #Metoo movement has been accused of being unfocused, without a clear purpose, and at times a threat to men falsely accused (North, 2018), the movement has upended public conversation about this health issue for women and others globally. How the sustained attention on the movement and related issues is used for addressing these women’s health, safety, well-being, and policy change remains to be seen.

The digital body can be transformed into a political stance by a digital act and one that can translate into material changes. Tarana Burke explains she thinks the “destigmatizing effect #Metoo represents a greater gain than anticipated risks” and that “There is inherent strength in agency. And #Metoo, in a lot of ways, is about agency” (Brocke 2018). The way #Metoo has been discussed in a variety of news articles echoes this sentiment—participants often felt empowered, part of something larger, less ashamed when adding their voice to the #Metoo community.

#Metoo: What Did Not Metabolize

Although #Metoo generated space for sexual assault narratives by forcing viewers to consume content, I want to pay attention to Landecker’s statement that metabolism “run[s] the operation of being a body” (Landecker 2013: 4). #Metoo certainly disrupted public discourse, allowing certain women to feel safe enough to express their tales of assault or harassment by feeling connected to a larger community. However, not all #Metoo narratives were integrated seamlessly into the “operation of being a body” (Landecker 2013). Verity Trott explains that not all survivors felt the same way, calling the feminist hashtag campaign “voyeuristic trauma porn” that disregarded the “high level of emotional labour from survivors but demands nothing from the perpetrators” (2021: 1125). Moreover, not all survivors felt safe in sharing their stories of sexual assault—despite the presence of other stories.

Here, Golumbia’s exploration between users and CRMs becomes generative ground for thinking through the ways in which platforms have historically both catered to individuals and abstracted their specific needs. He explains:

While the rhetoric of CRM often focuses on ‘meeting customer’s needs,’ the tools themselves are constructed so as to manage human behavior often against the customer’s own interest and in favor of statistically-developed corporate goals that are implemented at a much higher level of abstraction that the individual[.] (169)

Following Golumbia’s account of computational logics that automate and naturalize political power, I read the hashtag as a kind of techne structuring stories to cohere as movement. This formulation of tools that meet the customer’s needs—in this case, a platform’s so-called democratic dialog prompt to share using the hashtag #Metoo—is levied against the interest of individual contributors. In fact, the hashtag is, itself, a construction that manages human behavior at a high level of abstraction. Individual contributions are absorbed into larger historically specific, deeply political projects. #Metoo participates in the logics Golumbia outlines: it amplifies, recirculates and constrains testimony through platform architectures which privilege certain repetitions.

Not all bodies, #Metoo reveals, are valued the same. Importantly, then, some kinds of zombie hunger remain indigestible, despite the ways #Metoo forces the consumption of particular digital identities. Technological tools and digital media are not absented or immune from their situatedness.[10] Kember and Zylinska offer some insight as “to what extent and in what way ‘human users’ are actually formed–not just as users but as humans–by their media” (2014: 12). For #Metoo, understanding that media –and its consumption– as imbricated in human cultural, social, political, and economic systems is important to push against narratives of technology as liberated from the concerns of race, class, and gender.[11]

#Metoo is not physically present, but a product of the Anthropocene where bits/bytes are organized across bodies. #Metoo organizes data in a horde–a very different kind of archiving practice than the traditional archive which is in a locatable space with defined parameters of what types of content are worthy of memorialization. Again, social media archival sites pose different challenges for contemporary historians such as privacy concerns, methods of swift retrieval, deleted accounts among other things. Foucault explains that archives exercise a particular kind of discursive power, functioning as the “system that establishes statements as events and things” (Foucault 1972: 137). Value, significance, and authority become associated with items stored and cared for in an archive. By transitioning items into an archive, values of cultures are rendered visible–these are the ways an archive helps form “events and things” which, in turn, outline what types of events are permissible.

Another important contour: “you” are implicated, “you” are metabolized. When survivors uploaded their stories and used the hashtag, they participated in a decentralized archive. The platforms of sites such as Facebook and Instagram enable self-archiving practices that depart from traditional archiving power structures. As Rebecca Lemov (2017: 254)) explains:

Self-initiated nonstate archives tend to embody a different set of power and control nodes, a difference perhaps most easily embodied in the contrast between the relations Michel Foucault described in Discipline and Punish (in which the pervasive ‘eye of power’ spread disciplinary and dressage-like techniques that are absorbed through a network of power relationship) and the processes he examined in The History of Sexuality volumes 2 and 3….self-archive, a powerful paradox is at work. The imperative to optimize the self through archiving it is accompanied by a concomitant desire to ‘outsource; responsibility for choices.

Lemov is right to focus on the ways “nonstate archives embody a differ set of power and control nodes” that have to do with panoptic impulses, regulated behavior to “optimize” the self for absorption and consumption. Digital self-archives, such as Facebook and Instagram, are unquestionably sites of knowledge production. Social facts, as Ann Laura Stoler (2017) indicates, help shape which knowledge is considered qualified. In digital spaces, the process of converting social fact to authoritative knowledge is imperative to the reconfiguration of power. Only certain knowledges are saved, waiting to be resurrected. On Facebook and Instagram, this inherited imperial practice shifts, becomes harder to see, and requires a different assemblage of historically specific materials to trace how power is exercised over bodies.

Even in this moment of rupture, #Metoo’s imagined community still largely upholds what Gayle Rubin calls a “hierarchical system of sexual value. (Rubin 2007: 171). Due in part to criminalization and a long tradition of dehumanization, the vulnerable population of self-identifying and self-reporting sex workers failed to be integrated successfully into the larger narrative of #Metoo. Melony Hill, Baltimore resident and sex worker, explained after disclosing her experience with sexual violence that “she’s gotten messages saying she deserved to be sexually assaulted…‘They don’t want to include women like me….They’ll say we’re just whores anyway — ‘How can you sexually assault a whore?’ I’ve had that said to me multiple times” (Cooley 2018). The piece continues with stories from the women whose sex worker status positions them outside the generative potentiality of #Metoo. Sex workers occupy a space on the bottom of the hierarchy as a part of a “criminal sexual population based on sexual activity” (Rubin 2007: 171). Because sex work falls outside normative sexual activity, cultural narratives often dehumanize these laborers as “dangerous” or “inferior undesirables.”[12] Professional dominatrix J. Leigh Brantly expresses this concern when she states, “they aren’t ‘perfect victims” (Rubin 2007: 172). These examples illustrate how the conventions of social media’s zombie hunger do not promise full liberation—many other socially constructed others remain outside bandwidths of acceptability for horde hunger.

Sex worker experiences are not the only vulnerable, less metabolized. There are other intersectional concerns–women of color and working-class women are often left out of the conversation. A white actress launched #Metoo into the cultural imaginary, despite Tarana Burke’s Me Too campaign which started a decade before. Vice President for Education and Workplace Justice at the National Women’s Law Center Emily Martin explains, “‘There has not been enough attention to the way sexual and racial harassment intersect and the ways a woman’s racial identity can target them for harassment” (Jones 2018).

Without attention to intersectional goals, digital movements run the risk of unintentionally reproducing the subordination of certain bodies. Trott (2021) explains intersectionality is a crucial framework to address some of the issues women of color, women with disabilities, women outside the United States,[13] and queer women faced while attempting to have their experiences successfully metabolized. She explains the framing of Milano’s tweet alongside the spreading sentiment that “we’re all victims and should stand together” excluded “experiences of men, transmen, and nonbinary folk, with the latter groups experiencing a higher rate of sexual violence” (Trott 2021: 12). The exclusion of trans and nonbinary folks in #Metoo speaks to a larger rupture within mainstream feminist activism. Trott indicates the flattening of all survivors as the same within digital platforms fails to properly account for how marginalized groups operating within systemic oppression often have greater chances of experiencing sexual assault and violence. Intersectional frameworks reveal not only which narratives are deemed consumable (or hungered for) but also traces how both algorithms and digital norms work in tandem to amplify certain narratives at the expense of others.

#Metoo, Tactical Media, and Possibilities

From a certain vantage point, #Metoo might appear to be a neoliberal life narrative for the ways in which individuals named systemic harm and major white businessman were held legally accountable.[14] Gilmore explains that the neoliberal life narrative “features an ‘I’ who overcomes hardship and recasts historical and systemic harm as something an individual alone can, and should, manage through pluck, perseverance, and enterprise. In short, the individual transforms disadvantage into value” (Gilmore 2017: 89). However, there are distinct differences due to the interrelated, composite, zombie-like mass of people connected by a hashtag, and the words “me too.” This is not the story of an individual, but a story of scale.

Attention to these collapses of self/other and consumer/consumed helps us think about #Metoo where the same kind of zombie hunger forced users to consume the horror of sameness. The sameness here is the horror of the volume of sexual assault survivors, of violated physical bodies and newly wounded digital bodies. Being forced to consume content in this scaled-up way furthers the zombie hunger because it calls attention to differential life chances which exist under capitalism but typically disappear from notice.

The normative social protocol of going online and checking the live feed is part of the platform level mechanisms that allowed these testimonies to be seen and consumed. Understanding the slipperiness of the subject and self within neoliberal conventions of branding and self-commodification can reveal the gendered, classed and raced impacts of capitalism and how hunger can be used as tactical media, a disruption in normative procedures. Rita Raley explains that tactical media “engage in a micropolitics of disruption, intervention, and education” and that “tactical media activities provide models of opposition rather than revolution,” operating within the system of global capitalism and neoliberalism. Since tactical media are forms of art that form “temporary autonomous zones,” they open rather than foreclose possibilities for political transformations beyond their ephemeral temporalities (Raley 2009: 1, 151, 27).

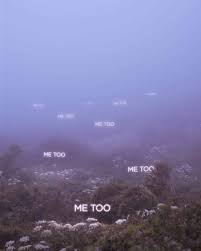

I read Victoria Seimer’s viral #Metoo digital artwork through zombie hunger as a form of tactical media (Seimer 2017). On Instagram, a particular image created by user @witchoria (Victoria Seimer)[15] and promiscuously[16] circulated by other users provides an example of a story that (as noted earlier) names wounds. User @witchoria which presents a haunted, foggy field in which no bodies are present. Instead, “me too” is spectrally rendered, repeated throughout the image. On Instagram, user zero @witchoria made her image accessible to “anybody who wishes to repost,” allowing her image to circulate in testimonial networks (Seimer 2017).

Zombie hunger is a flexible close reading strategy, one that can also be applied to visual texts; in turn, @Witchoria activates the same pleasures of consuming and being consumed. Since this image was created and meant to be shared, the image itself has the capacity to link bodies, and “make of others do” (Latour 2005: 9).

This agential image is noteworthy for a few reasons and requires a few different, yet knotted readings. Mitchell argues photographs have ritualistic value in social life meaning images desire and perform work, occupying an uncanny space as nonhuman actors that, through social imaginings, have power to regulate meaning or produce panic (2005). He indicates images are lifeform that occupy media ecologies where “personas and avatars [can] can address us and be addressed in return” (Mitchell 2005: 203). @witchoria’s photograph presents a natural landscape: a night-dark field, greenery, flowers, and a thick fog. However, this familiar woodland scene immediately becomes uncanny. The natural world fades away and the unnatural prevalence of sexual violence manifests in the glowing “ME TOO” that is repeated throughout the image, fading into the mist. @Witchoria’s composite photograph demonstrates the naturalization of systemic sexual violence. @witchoria flips the script of presenting idealized, normative, healthy bodies, choosing instead to withhold any bodies. She doctored her photograph to demonstrate the presence of an ill, highlighting wounds and trauma rather than shying away from such presentations. Rather than taking a photograph of something “true,” @witchoria generates a narrative photograph, blending elements of fiction and metaphor into her work. This imagining or phantasy is necessary for the recognition of her trauma.

@wichoria conjures a haunted space replete with zombie hunger which complicates the idea of the individual, both biological and social. On Facebook and Instagram, a digital body is always a composite being, warranted and circulating from the uploader, in tandem with other users, text, algorithms, and photographs. Such complex becoming builds from biologist Scott Gilbert declaration “We are all lichens,” meaning from a biological standpoint, humans are composite, symbiotic entities and not singular autonomous individuals.[17] If the individual is no longer a unified, singular biological entity, then this dispersed, composite fact is made reticent online, particularly in the case study of @witchoria’s widely disseminated image. Zombies are seldom singular; they gain full recognition in a zombie horde in which individual distinction is not the defining feature. Zombies gain meaning in relationship to each other, and when read against orderly, healthy bodies free from disease. Zombies are an act of translation, moving between life and death, singular and plural. Like the pronoun “you,” zombies occupy a space of general and individual distinction.

In contemporary imaginings, zombies lose their names–they cease to be individuals. Instead, they become a zombie horde, a collective monstrosity that is both human and nonhuman. @witchoria’s disseminated photograph, the name of the particular user is not nearly as important as the admission: “me too.” Articulating the violence and generating a wound gains potency through the horde-like mechanism of the hashtag. When the hashtag is followed on Instagram, an overwhelming mass of images—of trauma—materializes. Here we have a haunting. Here we have a story that translates wounds.

Each user that elected to use @witchoria’s image for #Metoo participated in an act of translation, which strikes me as being related to the classic sense of repetition. Writing “Me Too” simultaneously decenters and preserves the author–or uploader.[18] The traumatic experience is distilled into a caption, gaining new life when posted online. Attaching an individualized narrative, however long or sparse, does the work of “living on” through “repetition with a difference” (Massumi 2002: 16). It is actually the frequency and pattern that given the #Metoo endemic and temporal meaning (Massumi 2002: 39).

Within the specific case of #Metoo, the “me” occupies a different type of first-person experience. The “me” of #Metoo names frequency as its temporality. The “when” of trauma is less important than the prevalence. Like the “ME TOO”s in @witchoria’s piece, users gain meaning through their relationship to each other, the archival tool of the hashtag, and the algorithms that mark posts for visibility and circulation.

#Metoo also functions as a “component of passage that transforms engaged bodies into something other than what they have been.” In this case, the Facebook or Instagram body is transformed by a digital act, by its relationship to other users and nonhuman actants. Through the frequency of #Metoo, the wound of the corporeal body is transformed into a viral wound of the digital body.

Conclusion

The limited integration of all stories of sexual assault is indicative of zombie hunger—the story of the mass, of the horde, of what normative conventions demand stays repressed and other— dead, even. By understanding #Metoo as a narrative structure that utilizes metabolic functions, it becomes possible to better trace the conventions which govern possibilities for users.

But like the zombie, there is power in fragmentation, in recognizing the human within the horror. Even with flaws and limitations, #Metoo wakes collective hunger, places power in abundance, in survivors using the platform conventions of looking and eating which often replicate violences of the material world as a mechanism to name structural harm. Such uncanny acts of zombie hunger cause a reckoning, a confrontation of this is how the world works.

Metabolized narratives account for cultural tastes. They enforce boundaries, regulating which lives are awarded value. While these value designations certainly happen “offline,” the digital world renders the process of regulation more visible. The zombie like #Metoo will not be satiated, nor will liberation come through this act alone. Although Mark Zuckerberg claims a kind of celebratory ownership over the way movements such as #BlackLivesMatter and #Metoo connect people, Golumbia points out the same tools “contribut[e] to the destruction of the democratic social fabric, the destabilization of journalism’s critical function in democracies, and the promotion of hate and disinformation.” (Golumbia 204: 38). This is the danger of zombie hunger—all kinds of narratives can metabolize through the pleasures of consumption.

Without material action, the social body has remained haunted. In a post-Covid internet during the second Trump administration, the afterlife of zombie hunger has mutated. New hashtags speaking similar structural wounds have emerged. This is the affordance of the zombie: the afterlife of #Metoo persists, refuses rest, and is a continued site of undead political energy. At time of writing, #Standwithsurvivors, a hashtag associated with the victims of Epstein’s sex trafficking ring, is stirring, hungry for justice in legislative bodies.

Jeanette Vigliotti King is an Assistant Professor of Classical and Liberal Education at Flagler College Florida. She received her PhD from Virginia Commonwealth University in Media Art Text. A former graduate student of David Golumbia, she is interested in digital body construction within social media spaces, particularly the way digital bodies operate at the intersections of life/death, healthy/unhealthy, self/other.

References

Barthes, Roland. 1977. Image Music Text. London: Fontana.

Berlant, Lauren. 2007. “Slow Death (Sovereignty, Obesity, Lateral Agency).” Critical Inquiry 33, no. 4: 754–780.

Bloom, Jessica. 2017. “The #Metoo Photo Going Viral on Instagram.” Format, October 17. https://www.format.com/magazine/resources/art/me-too-wichoria-victoria-siemer-instagram.

Boellstorff, Tom. 2016. “For Whom the Ontology Turns: Theorizing the Digital Real.” Current Anthropology 57, no. 4: 387–407.

Bracewell, Lorna. 2021. Why We Lost the Sex Wars: Sexual Freedom in the #Metoo Era. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Brodeur, Nicole. 2017. “Strength in Numbers: A Mountain of #Metoo.” Seattle Times, October 17. https://www.seattletimes.com/life/strength-in-numbers-a-mountain-of-metoo/

CBS News. 2017. “#Metoo Floods Social Media With Stories of Sexual Harassment and Assault.” October 17. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/me-too-campaign-floods-social-media-sexual-harassment-abuse/

Caldeira, Sofia P., Sander De Ridder, and Sofie Van Bauwel. 2020. “Between the Mundane and the Political: Women’s Self-Representations on Instagram.” Social Media + Society (July). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120940802.

Carter, Julian B. 2007. The Heart of Whiteness: Normal Sexuality and Race in America, 1880–1940. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. 2008. Control and Freedom: Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. 2016. “Big Data as Drama.” ELH 83: 363–382. doi:10.1353/elh.2016.0011.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. 2017. Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Cooley, Samantha. 2018. “‘They Don’t Want to Include Women like Me.’ Sex Workers Say They’re Being Left out of the #Metoo Movement.” Time, February 13. https://time.com/5104951/sex-workers-me-too-movement/

Derrida, Jacques, and Lawrence Venuti. 2001. “What Is a ‘Relevant’ Translation?” Critical Inquiry 27, no. 2: 174–200.

Gieseler, Carolyn. 2019. The Voices of #Metoo: From Grassroots Activism to a Viral Roar. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Gilbert, Scott F., Jan Sapp, and Alfred I. Tauber. 2012. “A Symbiotic View of Life: We Have Never Been Individuals.” The Quarterly Review of Biology 87, no. 4: 325–341.

Gilmore, Leigh. 2017. Tainted Witness: Why We Doubt What Women Say About Their Lives. New York: Columbia University Press.

Gitelman, Lisa. 2006. Always Already New: Media, History, and the Data of Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Golumbia, David. 2009. The Cultural Logic of Computation, Cambridge: Havard University Press.

Golumbia, David. 2024. Cyberlibertarianism: The Right Wing Politics of Digital Technology. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Haraway, Donna J. 1991. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. London: Free Association Books.

Haraway, Donna J. 2013. “SF: Science Fiction, Speculative Fabulation, String Figures, so Far.” Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology, no. 3 (November).

https://doi.org/10.7264/N3KH0K81.

Haraway, Donna J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Harding, Sandra. 1992. “After the Neutrality Ideal: Science, Politics, and ‘Strong Objectivity.’” Social Research 59, no. 3: 567–587.

Harding, Sandra. 2008. Sciences from Below: Feminisms, Postcolonialities, and Modernities. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Jones, Charisse. 2018. “When Will MeToo Become WeToo? Some Say Voices of Black Women, Working Class Left Out.” USA Today, October 5. https://www.usatoday.com/story/

Kauffman, Michelle R., et al. 2021. “#Metoo and Google Inquiries Into Sexual Violence: A Hashtag Campaign Can Sustain Information Seeking.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36, no. 19–20: 9857–9867. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519868197.

King, Jeanette Vigliotti. ““I Feed You My Limbs”: Haunting and Hunger in Sally Wen Mao’s “Live Feed””, Screen Bodies 10, 1 (2025): 1-12, https://doi.org/10.3167/screen.2025.100102

Landecker, Hannah. 2013. “Metabolism and Reproduction: The Aftermath of Categories.” Life (Un)Ltd: Feminism, Bioscience, Race 11, no. 3: 1–10.

Landecker, Hannah. 2015. “Being and Eating: Losing Grip on the Equation.” BioSocieties 10, no. 2: 253–258.

Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lemov, Rebecca. 2017. “Archives-of-Self: The Vicissitudes of Time and Self in a Technologically Determinist Future.” In Science in the Archives: Pasts, Presents, Futures, edited by Lorraine Daston, 247–270. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Loney-Howes, Rachel, Kaitlynn Mendes, Diana Fernández Romero, Bianca Fileborn, and Sonia Núñez Puente. 2021. “Digital Footprints of #Metoo.” Feminist Media Studies (February): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2021.1886142.

Massumi, Brian. 2002. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Noar, Seth M., et al. 2018. “Can a Selfie Promote Public Engagement with Skin Cancer?” Preventive Medicine 111: 280–283.

Raley, Rita. 2009. Tactical Media. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Rippl, Gabriele, Philipp Schweighauser, and Manuel Löffelholz, eds. 2013. Haunted Narratives: Life Writing in an Age of Trauma. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Rubin, Gayle S. 2007. “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality.” In Culture, Society and Sexuality, edited by Richard Parker and Peter Aggleton, 143–178. London: Routledge.

Sheehan, Tanya. 2011. Doctored: The Medicine of Photography in Nineteenth-Century America. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Siemer, Victoria. 2017. “#Metoo.” Instagram, October 16. witchoria.com/post/166469451587.

Smith, Sharon G., et al. 2017. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010–2012 State Report. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/46305.

Stoler, Ann Laura. 2010. Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Trott, Verity. 2021. “Networked Feminism: Counterpublics and the Intersectional Issues of #Metoo.” Feminist Media Studies 21, no. 7: 1125–1142.

Turner, Fred. 2010. From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Vagianos, Alanna. 2017. “The ‘Me Too’ Campaign Was Created by a Black Woman 10 Years Ago.” Huffington Post, October 17. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/the-me-too-campaign-was-created-by-a-black-woman-10-years-ago_n_59e61a7fe4b02a215b336fee.

[1] For consistency, the hashtag associated with this event will be stylized as “#metoo.”

[2] Alyssa Milano (@Alyssa_Milano), “Suggested by a friend: If all the women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote ‘Me Too” as a status, we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem. If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet.” Twitter, October 15 2017. https://twitter.com/alyssa_milano/status/919659438700670976

[3] For an explanation of how Facebook hashtags work and the date of introduction, see Joanna Stern,”“#Ready? Clickable Hashtags Are Coming to Your Facebook Newsfeed,” ABC News online, last modified June 12, 2013, https://abcnews.go.com/Technology/facebook-adds-clickable-hashtags-newsfeed-posts/story?id=19383505

[4] For fuller discussion of the pronoun you in social media spaces, see Wendy Chun’s “Big Data as Drama.” ELH, 83: 363-382 and Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

[5] See Sandra Harding. “After the Neutrality Ideal: Science, Politics, and ‘Strong Objectivity.’” Social research. 1992;59(3):567-587

[6] For a fuller discussion of the idealized, white, thin body see Julian B Carter.. The Heart of Whiteness: Normal Sexuality and Race in America, 1880–1940, (Ukraine: Duke University Press, 2007);

[7] For further discussions of online/offline. Please see Tom. Boellstorff “For whom the ontology turns: Theorizing the digital real.” Current Anthropology 57, no. 4 (2016): 387-407; For a robust discussion of the politics of search, please see Safiya Umoja Noble, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2018).New York University Press, 2018.

[8] For a case study of the inverse (a selfie displaying bodily sickness) that generated public awareness see Noar, Seth M. Noar et al., “Can a selfie promote public engagement with skin cancer?,” Preventive medicine, 111 (2018): 280-283.

[9] Smith SG, Chen J, Basile KC, Gilbert LK, Merrick MT, Patel N, Jain A., 2017, The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010–2012 state report. Center for Disease Control and Prevention https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/46305 and Kearl H The facts behind the #Metoo movement: A National Study on Sexual Harassment and Assault. 2018 Stop Street Harassment, Reliance, and the UC San Diego Center on Gender Equity and Health http://www.stopstreetharassment.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Executive-Summary-2018-National-Study-on-Sexual-Harassment-and-Assault.pdf

[10] See Sandra Harding, Sciences from Below: Feminisms, Postcolonialities, and Modernities. (United Kingdom: Duke University Press, 2008). Harding says knowers are composite beings–complex and embedded in sociohistoric situations, claiming there is “no impartial, disinterested, value-neutral, Archimedean perspective.” (59). See also Donna Jeanne Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, (United Kingdom: Free Association Books, 1991) and Gitelman, Lisa. Always Already New: Media, History, and the Data of Culture. (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2006). Gitelman explains media are not just tools of research but are sites “dynamically engaged within and as part of the socially realized protocols that define…sources of meaning” (153).

[11] See Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Control and Freedom: Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics, (United Kingdom: MIT Press, 2008) for a good discussion of the rhetorical work of the word “cyberspace.” See also a critique of widespread digital utopianism: Fred Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010). See also Noble who argues “(s)earch results are simply more than what is popular. The dominant notion of search results as being both ‘objective” and ‘popular” makes it seem as if misogynist or racist search results are simply a mirror of the collective” (Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines are Racist, 36).

[12] Rubin, 172.

[13] For a global non-US perspective on 2017’s #Metoo, see Pain, Paromita. ““It took me quite a long time to develop a voice”: Examining feminist digital activism in the Indian# MeToo movement.” new media & society 23, no. 11 (2021): 3139-3155 and Loney-Howes, Rachel, Kaitlynn Mendes, Diana Fernández Romero, Bianca Fileborn, and Sonia Núñez Puente. 2021. “Digital Footprints of #Metoo.” Feminist Media Studies, February, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2021.1886142.

[14] See also Lorna Bracewell, Why We Lost the Sex Wars: Sexual Freedom in the #Metoo Era, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021). While not a discussion on stories that fail to integrate, Bracewell’s Why We Lost the Sex Wars examines how the criticisms of #Metoo from both the conservative right and progressive liberals often reinforce the neoliberal idea that sexual assault is linked to personal responsibility and not related to structural harm. Bracewell argues for the need to reject a liberal sexual politics to instead imagine a feminism that can contest the classed, raced and gendered structures and norms which support and sustain sexual injustice.

[15] See Jessica Bloom, “The #Metoo Photo Going Viral on Instagram.” Format, last modified October 17, 2017, https://www.format.com/magazine/resources/art/me-too-wichoria-victoria-siemer-instagram.

[16] See Donna J. Haraway. 2013. “SF: Science Fiction, Speculative Fabulation, String Figures, so Far.” Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology, no. 3 (November). https://doi.org/10.7264/N3KH0K81.

[17] For further development of this idea, see Gilbert, Tauber, and Sapp. “A Symbiotic View of Life: We Have Never Been Individuals,” 326.

[18] See Derrida, Jacques, and Lawrence Venuti. “What is a” relevant” translation?.” Critical inquiry 27, no. 2 (2001): 174-200. He explains the act of translation not only “prolong[s] life, living on, but also life after death” (199). Derrida’s formation of translation also pushes boundaries between life and death, much like the undead aspect of the zombie.