by Natania Meeker and Antónia Szabari

I.

The second half of the twentieth century witnessed the rise of a peculiar cinematic genre: plant horror. This somewhat embarrassing product of post-war Hollywood proliferated throughout the century and soon went global, although without much critical fanfare. Its ascension has its origins in the burgeoning consumer culture of the 1950s, which cultivated an audience for low-budget sci fi and horror, and in the onset of the Cold War, which provided a fertile environment for fears of invading aliens, vegetal or otherwise. Yet the genealogy of plant horror is multiple. Defining influences include both developments in plant science and changing literary and visual representations of an animate natural world. At least in the North American context, its genesis can be traced as far back as Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “The Fall of the House of Usher” (1839) and the latter’s fascination with the disturbing effects of “the sentience of all vegetable things.”[1]

The Duffer Brothers’ television series Stranger Things (2016-present) can lay claim to plant horror as part of its pedigree, although initially it does so almost discreetly, with fleeting references to classic entries in the plant horror tradition either evoked in passing or positioned in the background of various shots, such as a poster from Sam Raimi’s 1981 The Evil Dead. As the series develops, these references multiply and eventually move more consistently into the foreground. A tree serves as a portal to another dimension; a monster resembles an animate, blood-thirsty flower; forests provide not just greenery and escape but also a means by which the dark terrain of the Upside Down can take hold of reality; and a blighted field of pumpkins leads to the discovery of a kind of supernatural root system undergirding the small town in which the series is set.

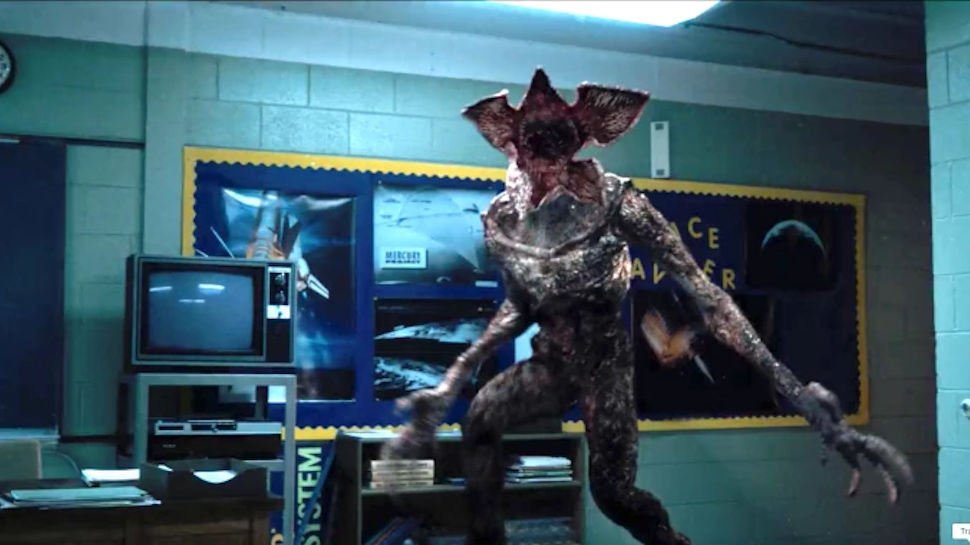

Stranger Things tells the story, often from the perspective of children on the cusp of adolescence, of the gradual interpenetration of two worlds: the “normal” world of Hawkins, Indiana and the alternative dimension of the Upside Down. This second world, connected by portals to Hawkins, is a horrifying, indeed apocalyptic, zone into which various characters stumble or are thrust. The specifically vegetal qualities of the Upside Down are initially less striking than the humanoid shape and animalistic thirst for blood of the first season’s central monster: the Demogorgon, named after the Dungeons and Dragons character known as the Prince of Demons. Yet this figure, which roams the Upside Down in search of prey and eventually moves into the space of reality as it is represented in the series, has a face in the shape of a monstrous carnivorous plant—which is to say no face at all, but only a mouth, exposed by fleshy petals that open to reveal a central orifice filled with teeth. In another nod to the plant horror tradition, the Upside Down, described in terms borrowed from Dungeons & Dragons as the “shadow material plane of necromancy and evil magic,” is overwhelmed by vegetal matter, albeit decaying and often intermixed with animal qualities or organs.

The Upside Down dimension is at once horrifyingly in touch with the human world, invading and penetrating it at inopportune times and in many different forms, and this world’s uncanny and alien bad copy—its disgusting and disturbing duplicate. In this double operation the Upside Down is reminiscent of the pods from the 1956 and 1978 Invasion of the Body Snatchers films, in which plants serve as replicas of the humans whose bodies they take over. The thematic preoccupation with “fake” vegetal copies of “real” human beings or worlds is underscored not just by the vegetal attributes of the Upside Down generally but in an early scene from the first season of Stranger Things in which cotton is being pulled from the counterfeit corpse of the young Will Byers (played by Noah Schnapp). Will is the first human to be lost, as far as the viewer knows, in the alternate dimension. In short, the aesthetic forms and tropes of plant horror structure and inform the series, although they are not always its most obvious focus.

At the same time, the Duffer Brothers (Matt and Russ Duffer) famously borrow heavily from the defining features of well-known 1980s genre films, including perhaps most prominently the oeuvre of Steven Spielberg.[2] As a master of the contemporary melodrama, Spielberg updates the genre by mixing it with speculative or fantastic elements. Stranger Things is set in the early 1980s—the first season begins in 1983—in a more or less middle-class housing development that strongly evokes the Southern Californian suburban settings of films like Spielberg’s E.T. (1982), although it does not fully replicate these settings. The series gestures with care and a certain obsessive love toward experiences and cultural artifacts from the “real” 1980s as well as the most memorable episodes from those of Spielberg’s (and, to a certain extent George Lucas’s) films that appeared during this same period. The Duffer Brothers’ portrayal of Hawkins also emphasizes, in a highly Spielbergian mode, the experience of children who are profoundly and in a sense irretrievably alienated from their parents, whose bourgeois domesticity covers over pervasive trauma. The invading alien force of the Upside Down exposes the hypocrisy and power dynamics that structure private life, as parents are forced to confront their own inability to care for their children, and children are obliged to bear witness to the stupidity, witless desires, and empty conformity of their parents.

Hawkins is also in thrall to an institutionalized, government-sponsored scientific agency—supposedly a branch of the Energy Department—that not only has unleashed the monster to begin with but has been engaged for some time in a series of sinister and family-destroying experiments.[3] Here we are reminded of the paranoia around “big government” fostered in the Reagan 80s, and indeed the series contains direct references to the election of 1984, with the display of yard signs (Reagan/Bush in the home of the Wheelers, the most self-consciously bourgeois household in the film, and Mondale/Ferraro in the yard of the Henderson family, consisting of a single mother and her quirky son Dustin).

The various tropes drawn from films of the period are gradually resituated in vegetal contexts, so that the Energy Department turns out to be engaged in a kind of strange harvesting operation, which involves culling and pruning the invading tendrils of the plant life from the Upside Down. The characters’ familial traumas and divisions are themselves not only infected by but restaged within the vegetal world of the Upside Down. Moreover, the wide streets down which groups of kids ride their bikes, and other archetypal “small town” attributes of Hawkins, are repeated within the Upside Down, this time covered in vines, branches, and strange floating spores, as if not just the human characters but the space itself had been consumed by rapacious vegetality. The Upside Down and Hawkins turn out to be connected to one another by root systems that allow passage both between dimensions and across any given zone.

Stranger Things thus references not only vegetal monsters—which act to a certain extent as individuals and share characteristics with animals—but also forests and fields where plant life maintains a less individuated presence. Unlike the suburbs of Southern California that often serve as a privileged setting for the 80s films referenced in the series,[4] Hawkins is notable for its vegetation: forests, hanging vines, fields full of pumpkins and houses that are framed by plants of many kinds, both wild (or “feral”[5]) and domesticated.[6] The camera lingers over images of vine and root systems to evoke a more explicitly rhizomatic vegetality: in these contexts, plants appear as networks, rather than as animal-like desiring individuals. In episode six of season one, the iconic red letters of the title fade into an image of dark forests framed by the outlines of the words, suggesting that the strange, speculative elements of the series reside within these collective plant bodies. This de-individuated vegetal mode is visible both in Hawkins and in the Upside Down. In fact, it seems to be the connection, on the visual plane of the film, between the two realms. For example, the portal that appears in the forest outside Steve Harrington’s (Joe Keery) house takes the form of membranous, decaying vegetal matter which opens a cut in the bark of a tree; this opening is later sutured and solidified into bark as soon as Steve’s girlfriend Nancy Wheeler (Natalia Dyer) is rescued from the Upside Down and comes back out through the portal. In this scene, the individual tree is a point of entry into a space where plants appear not as individuals so much as masses, groups, bunches, and lines, but the tree itself is part of the forest, which represents its own kind of rhizomatic multitude.

Stranger Things’ extensive citations of 1980s middle-brow cinema and culture come across as much more poignant and, paradoxically, more authentic than the somewhat generic images from plant horror. Indeed the former are what the films are probably best known and appreciated for. Yet the many evocations of plant horror nonetheless remain worthy of consideration in the series even though, or precisely because, they are not invested with as intense a nostalgia as some of the other pop culture references. In fact, taken as mere throwbacks to an earlier moment in U.S. culture and politics, the references to specific plant horror films might be considered a red herring. It is not so much the recollection of a particular time—in this case, the 1980s—in its minute details that matters where the plants are concerned, but the way in which the tropes drawn from this era are subtly reconfigured by Stranger Things to invest the memory of the decade with a vegetal quality. The lingering vegetal presence in the series draws the past closer to our own, more ecologically-focused moment. In other words, where the plants are concerned, the 80s nostalgia of Stranger Things points toward the future. But it does so not just by (re)writing the earlier period as infested by plants but by invoking the structuring force of this particular decade on our present.

The increasingly marked vegetality of the series is situated in the context of a general reflection on the relationship of the 1980s to consumption and commodification. Stranger Things stresses the attachment of this period to cultural artifacts as sources of affect and identity formation, a dynamic that has arguably grown only more intense over time. The series lingers lovingly over images of the ambivalent commodification of culture, including narratives and “souvenirs” of 1960s rebellion, that is one of the hallmarks of the 1980s, as Jeffrey T. Nealon has explored in his book Post-Postmodernism.[7] Economically, as Nealon points out, the decade was shaped by the ongoing deterritorialization of capital, “floating flexibly free from production processes,”[8] and the rise of the finance sector and financial speculation, which brought with it increasing concentrations of wealth and heightened social, economic, and political inequality. At the same time, the consumption of particular cultural products began to work as a form of biopolitics, which allowed for identities to be formed and defined. As Nealon puts it, “The rock n’ roll style of rebellious, existential individuality, largely unassimilable under the mass-production dictates of midcentury Fordism, has become the engine of post-Fordist, niche-market consumption capitalism. Authenticity is these days wholly territorialized on choice, rebellion, being yourself, freedom, fun . . . .”[9] The series plays with this tension throughout, with its images of bands of children working hard to outrun the adults who seek to control them. Yet these images themselves inevitably evoke not just the pleasures of childhood resistance to adult authority but Spielberg’s own representations of such bands, which continue to circulate as highly successful (nigh iconic) commodities.

B-grade horror, which takes on cult-like status in and around the 1980s, particularly in the films of Sam Raimi, John Carpenter, and Wes Craven, is likewise caught in the contradictions symptomatic of an era that is nostalgic for earlier moments of social and political critique and activism. This is true of plant horror as well as of other entries in the genre. Is the vegetal Upside Down the figuration, in fleshy, pulpy terms, of the invisible, speculative agency of capital that invades the lives of so-called ordinary Americans without always being acknowledged, at least in the suburban context of the series? Is Stranger Things an Invasion for the twenty-first century? Plant horror has often delighted in lending capitalism a particularly vegetal power. For instance, Philip Kaufman’s 1978 remake of the Invasion of the Body Snatchers (set in San Francisco) protests the globalization of U.S. cinema that arrives, a year earlier, with the Star Wars franchise. But Kaufman’s film also reveals the power of this globalization to interpellate audiences in ways they find appealing. Here the global economy is shown to function along vegetal lines; plants both attract and replace the humans who are drawn to them. Kaufman’s Invasion rewrites the 1956 pods as the figures of a standardized globalized culture, while also making them seductive or at least fascinating envoys from an active alternative reality.

Stranger Things suggests that there are new pleasures and dangers to be found in the strange, niche appeal of plant-themed horror and its critical take on globalization. The decentered operations of the plant-like forces inherent in the Upside Down (both monstrous and rhizomatic) contribute to but also upend and destabilize the work done by the evil government agency, itself in thrall to a Cold War project. The first portal to the Upside Down is opened in a misguided attempt to make contact with a Soviet agent; the Upside Down works as a zone of global connectivity even before it is fully vegetalized. As the series develops, conspiracy theories generated out of an older Cold War paranoia meet those of the globalized free markets, and both are reconfigured as the networked vines and tunnels of the Upside Down, doing their invisible work. From this vantage Stranger Things becomes a pessimistic reflection on the 1980s as a moment to which we remain sadly, even monstrously, indebted—economically even more so than culturally—a period when we might come to realize the rhizomatic power of capital both to sustain us and to destroy the world as we know it. Plants serve as the privileged figures of this ambivalently double operation. But their action is at the same time something other than figural, as Stranger Things suggests. They also generate a range of affective transformations, particularly in the Upside Down, where speculative capitalism might be said to meet speculative fiction.

II.

In the larger context of their reflection on capitalism as a mode of affective entanglement—from which we struggle and fail to extricate ourselves—we can read the Duffer Brothers’ work as a revision of the Spielbergian canon. This rewriting may be consciously connoted by the comparative form “stranger” in the title of the series: stranger than what, the audience is obliged to ask? In his 80s corpus, Spielberg arguably brings a speculative dimension to a genre, that of melodrama, strongly associated with interiority and the domestic sphere. His films situate a melodramatic preoccupation with familial relationships in narrative contexts that draw from science fiction, the “creature feature,” and the thriller, thereby theoretically enhancing what might be called the speculative potential of the family romance as the latter is portrayed in middle-brow cinema. In films like Jaws (1975), E.T. (1982), and even Close Encounters of Third Kind (1977), however, this nominally speculative or explicitly fantastic dimension tends to be recuperated by a therapeutic mode, which emphasizes the power of alien forces not to disturb or disrupt familial ties—for this disturbance has already happened prior to the arrival of the extraterrestrial or creature—but to re-consolidate them. For instance, E.T. may at first destabilize the human world he accidentally inhabits but eventually serves to reaffirm and solidify family bonds that have been frayed by divorce. E.T.—the best therapy that money cannot buy!

Thus, aliens, undersea creatures, and various other monsters and strangers to our human world work in Spielberg’s oeuvre not necessarily to expand our sense of what is possible or even thinkable but to revitalize our attachments to family life and bourgeois domesticity. E.T. heals the trauma of the family wrenched apart; in Jaws, the struggle with the shark allows the hero to re-establish order and dominance over nature in his small town; even the extraterrestrials of Close Encounters confirm our sense of the beauty of the world and a cosmos not necessarily made by humans but harmonically in tune with them (the ending of the film notwithstanding).[10]

The Duffer Brothers preserve Spielberg’s thematic emphasis on moments of trauma and therapeutic healing even as they expand the speculative dimension of Stranger Things to render the world of the Upside Down less reparative than is typically the case with Spielberg. In this sense they move this key influence closer to a kind of open-ended horror, as we will discuss in the third section of this essay. One reason for this shift may be formal.[11] The Duffer Brothers are working in a serialized form, which lends itself to the stoking of plot tensions and the evasion of definitive resolution. Spielberg, on the other hand, does not typically operate in a serialized mode (with one notable exception to this rule being the Indiana Jones series).[12] But the Duffer Brothers are also clearly inspired by a Spielbergian emphasis on the power of what seems alien and strange to reaffirm that which is most familiar—to become a source of comfort in an uncomfortable world. This is the case even if their monsters just do not leave Hawkins alone at the conclusion of any given episode. The telekinetic girl Eleven (known as “El” and portrayed by Millie Bobby Brown) seems to serve this function; she is both otherworldly and, at times, the source of an empathy and love that parents in the series do not (or cannot) generally provide.[13]

But the Upside Down itself also becomes the source of a strange intimacy, although not one that reliably serves to heal or make whole the characters who find themselves trapped within it. This is part of what constitutes the comparative strangeness of the Upside Down: it generates affects that cannot be fully realized in a “normal” world, since they are unacceptable to or impeded by the bourgeois community that the films portray. Take for instance the scene at the end of the first season, when Will Byers is reunited with his mother Joyce, played by Winona Ryder, and the good-hearted but gruff town sheriff Jim Hopper (David Barbour), in a kind of uncanny family tableau. The placement of a crying Joyce holding Will’s supine body in her arms even evokes the Pietà, with Jim augmenting the scene of a mother holding the limp body of her child, into whom later life is breathed by the efforts of the two adults to perform CPR. This visual evocation of the Biblical holy family is later reinforced with the first season ending at Christmas, which brings with it a number of reconciliations. As Jim and Joyce attempt to reanimate Will’s lifeless body, a scene from the past, with Jim and his now estranged ex-wife helplessly watching while doctors in a hospital attempt and fail to resuscitate their daughter Sarah, is intercut with the images of Will, Joyce, and Jim in the Upside Down. This flashback suggests that the second moment of trauma, despair, and (possible) death is either a resolution to or repetition of the first. But Will, unlike Sarah, emerges alive, albeit inhabited by a monster. The scene in the Upside Down thus presents to viewers the possibility of a family made “whole” through the power of love. It stands in contrast to the many images of the families of Hawkins, Jim’s included, which are splintered by trauma and the failure to empathize. Still, this moment of healing can only take place within the apocalyptic frame provided by the Upside Down. The “broken” family is in a sense momentarily repaired, but the entire world around them has been destroyed.

Here the Spielbergian move toward a kind of reparative normativity is obviously in tension with the use of the Upside Down as a source of more destabilizing and unfamiliar affects—a tension that is heightened by the camera’s willingness to linger on the scene as well as by the soundtrack, Moby’s moody “When It’s Cold I Would Like To Die.” Is the series, we may ask, presenting us with an image of death followed by a birth? If so, as we have suggested earlier, it also commits to repeating the cycle ad infinitum, for the characters have to keep returning to the Upside Down to survive the traumas that in the “normal” world seem hardly bearable. The Upside Down is in this sense that place where, as Jim puts it, painful experiences are “shut up” in the mind—the site of the unconscious where both suffering and its cure are to be found. In a sense, then, the Duffer Brothers deploy the Upside Down as an affective zone that supplements and structures reality. It is a world in which families and connections might be briefly reformed, and thus not only the source of horror for the viewer and the characters but of different kinds of feelings, sensations, and connections than those sanctioned by the normal world (including, perhaps, queer sympathies that are otherwise unexpressed in the context of Hawkins, as we will suggest). The Upside Down thus allows the characters to survive the very destruction of the world against which they seem to be struggling, but to do so momentarily transformed: it engenders a mode of survival otherwise.

If Stranger Things has an ambivalent relationship to the tensions and contradictions structuring 80s popular culture, then, it also has an ambivalent relationship to Spielberg and the psychological narratives that he both popularizes and revises. It offers us images of trauma endured and assuaged only in the dark terrain of the Upside Down, and then only to reinitiate the cycle of violence. The presence of vegetal elements serves to distill and heighten this double ambivalence. The motifs drawn from 80s plant horror point to the nostalgic consumption of culture as a means by which capitalism invades and takes over the social body. But they also suggest the power of capitalism to maintain this body and to stimulate desire. More pointedly, the visual emphasis on plants as inhabitants of the Upside Down brings a latently ecological dimension to bear on what might otherwise be a set of throw-away references. In the Upside Down, plants overtake humans, whose sensitivity becomes a form of vulnerability and exposure.[14] Plant horror from the 80s invades and infects the world more generally.

The vegetalization of Spielberg’s universe makes it difficult, on the one hand, to see the plants as fully alien, in the sense that plant life inhabits both Hawkins and the Upside Down from the outset. When we do view plants in this way, as in the case of the monstrous Demogorgon, they notably fail to provide a satisfying or even viable resolution to the forms of alienation and trauma that mark family life. The animal-vegetal inhabitants of the Upside Down cannot hold the kind of therapeutic value that a character like E.T. so richly embodies. (We might note in this context that E.T. is a botanist: he loves, cultivates, collects, and heals plants, and eventually humans too. He does not become a plant!) A case in point is the baby Demogorgon lovingly baptized “Dart” (for “D’Artagnan”) by Dustin Henderson (Gaten Matarazzo). This creature is both enlisted as an alien other in need of care (in this sense functioning somewhat as El does for Mike Wheeler, played by Finn Wolfhard) and turns out to not quite fit the bill, even if Dustin continues to recognize their mutual attachment and to elicit acknowledgement from Dart when encountering him again in the Upside Down. Where the attachment to E.T. represents a kind of alternative nurturing—one which the mother in the film is incapable of fully providing—the connection to Dart seems both a product of parental lack of involvement and a repetition of this failure to care.

A similar ambivalence may be visible in El’s ventures into the Upside Down in obedience to the demands of the man whom she thinks of as her father (Dr. Martin Brenner, played by Matthew Modine), the head of the laboratory who in fact abducted her from her mother. El moves in and out of the Upside Down, initially in the mode of the dutiful daughter, and later, after she has escaped the laboratory, in service to her friends. Her forays into the alternate dimension suggest a kind of horrific shock therapy, but of course the outcome of these explorations is not healing but the repetition of the initial traumas of abandonment and abuse. El’s destruction of the Demogorgon in the first season is visually linked to the destruction of Brenner himself. But it does not resolve her alienation from the human world.

While season one ends on the ambivalent theme of death and resurrection, season two concludes on a more directly upbeat note, since the children seem to have momentarily remedied the many dysfunctions rampant in their social and familial circles. As we pass from the first to the second season, the psychodynamics linking the characters to one another seem to become more and more formulaic, and perhaps more and more “postmodern,” often self-consciously so.[15] The family life of the characters circles around the same set of tensions and challenges, which can never fully be overcome or even set aside. At the same time, the landscape in which these dramas are set becomes more interesting, more penetrative and more engaging. The series returns again and again to the therapeutic trope, while also revealing that the structures or affects of attachment and care have no hold over plants or the Upside Down generally, thereby enabling the series to continue.

In season two, strange things happen not only in the forest but also in the fields and in the soil under the town, which is mined by a gigantic system of tunnels filled with fleshy roots. According to the logic of seriality established thus far, season three promises another eruption of the Upside Down into the temporarily restored normal life of the town rather than proffering resolution to the traumas and lost attachments that have so far proliferated in the series and will, no doubt, continue to multiply. What will be yet stranger in season three? As critics and as viewers, we might hope that the next season will bring some more consistent intermingling or interpenetration of the two dimensions, in which Hawkins becomes the Upside Down (or vice versa), thus giving up the investment in the therapeutic mode. However, the series is also clearly invested in maintaining the separation between the two worlds, since this separation is key to drawing out the plot: the two are never allowed quite to meet or combine, even as the one becomes more and more infested by the other. The therapeutic dimension of Stranger Things is its own kind of dead end, since it holds out hope for a resolution of the conflicts structuring the series but can never allow for an encounter with the alien on its own terms. It is a mechanism that turns around itself. At the end of the second season, we can thus ask: what is the function of those vines, spores, and monsters from the Upside Down? Are they simply kept at bay to provide more catharsis for the characters, even as they also serve to repeat, again and again, the trauma of a formative loss?

III.

Alternately, we can claim that the series does occasionally allow us to imagine a fruitful expansion of its own speculative dimension in the references to plant horror, but it does so with hesitation and, again, ambivalence. Plants are admittedly monstrous, dangerous figures, but they are also systems that structure and connect characters, places, and even memories. In this capacity, they once again open up affective possibilities that the characters are loath to acknowledge, especially insofar as both seasons labor to reach an ending in which the normalcy of the human world is reaffirmed after the invasion from the Upside Down is momentarily kept at bay. However, alongside yet apart from this return to the normal, as the vines and spores gradually take over Hawkins and are allowed to proliferate in the visual landscape of an “ordinary” small town, the series hints at the idea that the invasion makes a new, “weird” intimacy available to viewers and characters alike.

One of the most powerful visual and cinematic tools used in Stranger Things is the intercutting of scenes from the two dimensions, so that the action appears to be taking place simultaneously in reality and in the Upside Down. This technique is used not so much to show parallel events in two different places as actions that happen at the same place and time but are experienced in different modalities or according to different rules. For example, in a scene from episode three (season one), in which Nancy is having sex with Steve, shots of their sexual encounter are intercut with images of a more properly monstrous relation, itself an intimate one, in which Nancy’s best friend Barbara “Barb” Holland (Shannon Purser) is attacked by the Demogorgon. This cinematic rendering of two dimensions as intimately linked in time and space, although they remain irreconcilable, makes possible the invention of alternate affects linking the characters. In this scene in and around Steve’s house, two distinct filmic locations (outside the house and inside the bedroom) are interlinked, with the former repeating, in disturbing ways, some of the gestures of affection and desire from the first. Here the cinematography of Stranger Things opens onto non-normative intimacies, and, perhaps tellingly, fan appreciation has grown over time for Barb as a queer character. The initial episodes of the first season indeed allude to a mutual affection connecting Nancy and Barb (in an implicit departure from the otherwise heteronormative plot), even if only to all but ignore this affection after Barb’s exit from the series.

The other character lost to the Upside Down, Will, is also described as “queer” by his mother, in a comment attributed to Will’s rigidly authoritarian father, and as “gay” by some of his bullying classmates. But this allusion is only made in the context of the oppressive and coercive social forces exerted against non-normative sexualities. A more tacit, visual acknowledgment of queerness occurs in the violent scenes when both Barb and Will are coopted, in very physical ways, into the fleshy and pulpy regions of the Upside Down.

Perhaps we can view the disturbing encounters between Barb and the Demogorgon, or Will and the creatures of the Upside Down, as moments of what Timothy Morton has termed “dark” ecology, in an allusion both to the gloomy aesthetics of such scenes and to their ability to challenge social norms and boundaries. In The Ecological Thought, Morton affirms, reflecting both on what he calls the “mesh” of evolution and the aesthetics of creature horror: “That’s the disturbing thing about ‘animals’—at bottom they are vegetables” (68). Dark ecology thus sets us in relation with things that are unavoidably real but also announce the receding of the familiar parameters defining our world and ourselves. Morton conceives this dark aesthetics as a non-individualist form of counter-culture, if not rebellion, one that operates nonetheless from within capitalism and the entertainment industry. Morton’s vegetables do not so much solicit connection as they allow us to stare down the holes that puncture our seemingly seamless reality. In the cases of both Will and Barb, however, Stranger Things seems to pose the question of the non-normative intimacies available in the Upside Down, perhaps its own space of rebellion or departure from normalcy, even as these intimacies are relegated to an apocalyptic zone and dropped from further narrative development. In this context, the vegetal is thus not given its own agency as a disruptor of the main plot. Barb and Will are abducted into the Upside Down; they do not enter it willingly. In Barb’s case, the initial encounter with the Demogorgon resembles an act of rape, and both Will and Barb are later shown to have been violently penetrated by the tendrils and tentacles of the Upside Down. The suggestion that this intimacy could be sought out is aggressively dismissed, then, in both instances. Here we should recall that the most famous plant horror scene in The Evil Dead is one of rape by a tree. The latent queerness of the Upside Down is clearly presented as a menace. As Jonathan’s father aptly remarks, pointing to the poster of the movie in his estranged son’s room: “Take it down! It is inappropriate.”

In the second season, however, the nature of the monster changes. At this point Stranger Things moves closer to imagining a threat—and a set of relations—that are more ecological than individual, more rhizomatic than merely monstrous. We discover that the Upside Down contains not one Demogorgon but a pack of “Demodogs” (a portmanteau word coined by Dustin), which are controlled by the elusive Mind Flayer (also called the Shadow Monster)—a force of nature that is itself not a single, centralized agent (although it does get visualized in the form of a giant spider) but a hive mind. Appearing as a ghostly presence only thanks to various now out-of-date technologies (most spectacularly a videotape played on a television set), the Mind Flayer evokes the evolution not of biological bodies but of electronic media, especially television, as these media come to inhabit and infest family life.[16] But the Mind Flayer is of course even stranger and more immediately horrifying than this sometimes frightening human intimacy[17] with electronic media, often seen as an intrusion into domestic and family life. U.S. popular film and television have long had a proclivity for capitalizing on the image of the “hive mind” to cultivate anxiety about collective identity early on associated with communist and socialist political and economic organizations—or simply with anything that seemed to threaten capitalist individualism. This is to a large extent the fear that Don Siegel’s 1956 Invasion of the Body Snatchers exploits quite effectively—the horror of losing one’s individual and authentic identity to an authoritative and de-individualizing social regime. The Mind Flayer not only cites this cultural trope but complicates it, in part by admitting this hive mind to be more American than has been generally or traditionally recognized, at least in the context of horror.

Tellingly, the Mind Flayer becomes another instance of the intersection of nature and technology that has been staged by the Upside Down all along. Critics like Akira Mizuta Lippit and Jussi Parikka have described the rich history of the entanglement of media with animals, with Parikka in particular zooming in on the use of insects for imagining new technological and mediatic possibilities including that of artificial intelligence.[18] Plant biologists Stefano Mancuso and Alessandra Viola, who have recently claimed that the existence of a “plant intelligence” opens up sci-fi-worthy possibilities for technological development, similarly characterize this intelligence as networked in a way akin to the insect hive mind or the behavior of human crowds.[19] The presence of the Mind Flayer draws out these intersections (between plant-animal and human, between ecologies and media, between outside and inside) thanks to its technological affinities and through its engagement with the children of Hawkins, who operate in swarms or decentered networks. Spielberg’s roving child bands take on a more ecological but also more technologically-informed cast.

Indeed, the “pack” of children who roam Hawkins is shadowed by the pack of Demodogs, a veritable army of adolescent plant-animal creatures. In Parikka’s terms, the children’s encounters with the Upside Down “reveal . . . a whole new world of sensations, perceptions, movements, stratagems, and patterns of organization that work much beyond the confines of the human world.”[20] It is the Upside Down that enables these new mediated experiences; in this respect it is a stand-in for the power that the intersection of the physical and the technological world has in shaping experience. The Upside Down is a hybrid zone where nature, body, affect, technology, and representation meet; it is more powerful than any board game, television program, or film can hope to be, because it supplements, intensifies, modifies, and outdoes the current configurations of techno-culture. This mixture of nature and technology is animate, agential, and actively intervening in our lives. In other words, media no longer haunts us but comes to live with us. As a life form, it is at once fleshy, rhizomatic, and machinic. An animal that is a vegetable, perhaps? From this perspective, we might begin to understand the effect of the Upside Down on the electrical grid—the first sign that something is wrong in Hawkins—as a symptom not just of the power of plant life but of the intertwining of vegetal and technological forces.

The Upside Down is not a figure of the excluded and exploited natural other or a cipher for the environment; it has a pulsating, vibrating materiality that is not human but swarming and spore-like, and it does not bring resolution to the social and psychological problems the characters face, or, when it does, it tends to affirm human exceptionalism. For all its aporia and hesitations, then, Stranger Things participates in the proliferation of a more intensely ecological mode of horror, one that privileges the plant not as a central character but as the end of character in the onset of the rhizomatic swarm. Moreover, the series underlines the links between the organic realm of the plant and the inorganic domain of the machine, troubling the divide between the two. At the same time, the series oscillates between exposing some of the traumas of American life—its submission to decentered flows of capital and to technologies that are marketed to individuals but operate by aggregating data and algorithms—and reverting to a therapeutic resolution to these traumas, however fleeting. Maybe we find here another inheritance from the 1980s, with its tentative attempts to organize a counter-culture from the elements presented to consumers in the service of corporate profiteering and the liberal marketplace, but in the guise of emancipation. Stranger Things offers us not so much a zone of outright rebellion as a mode of decisively weird bricolage.

Notes

[1] A small bibliography on plant horror has begun to emerge in recent years. See Dawn Keetley and Angela Tenga’s edited collection, Plant Horror: Approaches to the Monstrous Vegetal in Fiction and Film (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2016); T.S. Miller’s “Lives of the Monster Plants: The Revenge of the Vegetable in the Age of Animal Studies,” in The Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts 23.3 (2012): 460-479; and our own “From the Century of the Pods to the Century of the Plants: Plant Horror, Politics, and Vegetal Ontology,” in Discourse: Journal for Theoretical Studies in Media 34.1 (2012), 32-58. We note that a poster featuring Poe briefly appears in a high school classroom in Stranger Things.

[2] The influences on Stranger Things are obviously not only filmic. In interviews and discussions, the Duffer Brothers are explicit about the debt they owe to Stephen King as an author of horror fiction. Moreover, Spielberg is not the only important director cited by the series, which includes both direct and indirect references to the B-movie horror genre more generally, including the work of John Carpenter, Wes Craven, and the aforementioned Sam Raimi.

[3] This reference inspired a wonderful blog post hosted on the Energy Department site: https://energy.gov/articles/what-stranger-things-didn-t-get-quite-so-right-about-energy-department.

[4] Spielberg’s 1977 Close Encounters of the Third Kind, however, is set in Muncie, Indiana.

[5] See Matthew Battles’ Tree (New York: Bloomsbury, 2017) for an illuminating discussion of feral plants.

[6] The two film versions of The Invasion of Body Snatchers also make use of the de-individuating power of the plant trope, especially in the 1978 film, which highlights botanical references including the “grex” (a hybrid cultivar) and the vines that appear in the famous final scene. In Stranger Things, the defaced and defacing flowers, the dark forests, the fields, and the rhizomatic root systems are similarly invested with a defamiliarizing power.

[7] Jeffrey T. Nealon, Post-Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Just-in-Time Capitalism (Stanford, 2012), 2, 12.

[8] Ibid., 20.

[9] Ibid., 56-57. Stranger Things pays a kind of homage to this process with the character of Jonathan (played by Charlie Heaton), the big brother of Will Byers, whose fondness for The Clash is symptomatic of consumers who sought out narratives of rebellion while often remaining oblivious to the inefficacy of this consumption as a response to the economic processes that structured the decade. Jonathan Byers’s love for The Clash suggests the ability of free-market capitalism to harness the individualism of rebellion as a mode of consumption (even though Jonathan himself, the child of a working-class single mother, is marginalized and denigrated by the more well-to-do kids in the town). Of course, The Clash are aware of and sing elsewhere about precisely this paradox.

[10] Of course, the ending of Close Encounters, in which the hero leaves earth and his family behind, seems to entail an embrace of the alien and a rejection of the terrestrial life. Critics have remarked that this film is unusual in the context of an oeuvre that returns again and again to the primacy and psychological significance of the family.

[11] Another may be the effect of the Duffer Brothers’ attachment to Stephen King, whose horror fiction is typically less reparative than Spielberg’s work. Often, the trauma that both induces and is caused by the horror, in King, cannot be or fails to be resolved.

[12] We are indebted to David Tomkins for these observations.

[13] On the other hand, El is not consistently a benevolent or benign force (unlike, say, E.T.); the series remains ambivalent about her ability to heal, rather than generate, trauma.

[14] For an investigation of exposure as both theory and practice, see Stacy Alaimo’s Exposed: Environmental Politics and Pleasures in Posthuman Times (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016).

[15] Here we once again seem to be in the domain of the intensification of the post-modern identified by Nealon as “post-postmodernism.”

[16] In Haunted Media, Jeffrey Sconce describes the perception of television as “alive” (to the extent that people treated their television sets as living entities, often as intruders). Sconce’s focus is on the 1950s, but the prominent role of the television set in 80s family life is also underscored by the Duffer Brothers. Jeffrey Sconce, Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television (Duke, 2000).

[17] “Variously described by critics as ‘presence,’ ‘simultaneity,’ instantaneity,’ ‘immediacy,’ ‘now-ness,’ ‘present-ness,’ ‘intimacy,’ ‘the time of the now,’ or, as Mary Ann Doane has dubbed it, ‘a This-is-going-on’ rather than a ‘This-has-been…,’ this animating, at times occult, sense of ‘liveness’ is clearly an important component in understanding electronic media’s technological, textual, and critical histories.” Sconce, 6.

[18] Akira Mizuta Lippit, Electric Animal: Toward a Rhetoric of Wildlife (University of Minnesota Press, 2000); Jussi Parikka, Insect Media: An Archeology of Animals and Technology (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Pres, 2010).

[19] Stefano Mancuso and Alessandra Viola, Brilliant Green: The Surprising History and Science of Plant Intelligence, trans. Joan Benham (Island Press, 2015), 157.

[20] In Insect Media, Parikka thus describes “swarm intelligence” as a vital term for media theory, ix.

Leave a Reply