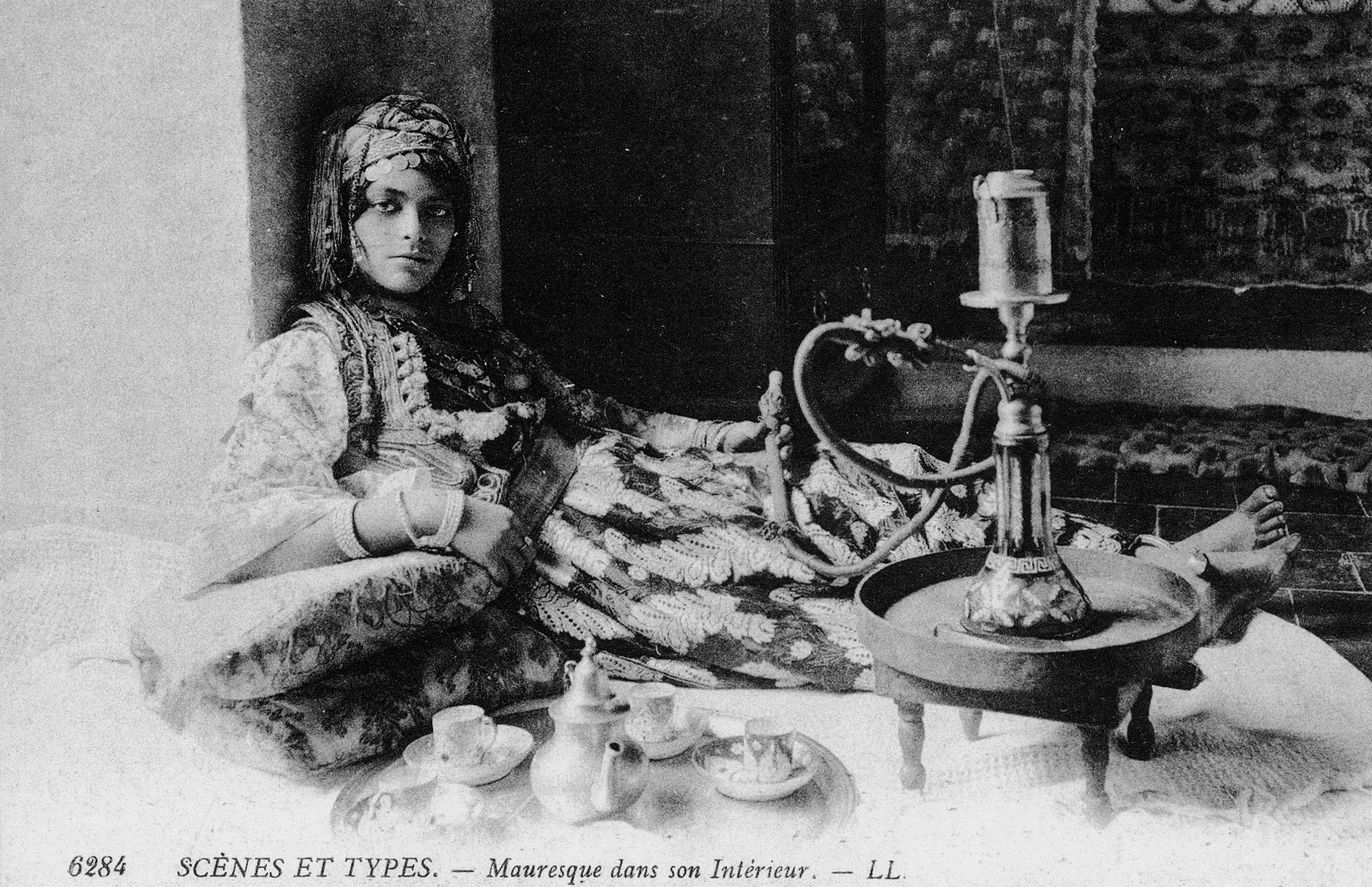

In his path-breaking book Orientalism (1978), Said does not mention the Maghreb by name (al-maghrib, “the place of the setting sun” in Arabic, a region designating northwest Africa, and in particular the French former colonies of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia), even though French Orientalism and imperialism play, alongside their British and American counterparts, a lead role in producing what Said calls “the Orient.” Said is deliberately vague in delimiting the contours of this much fantasized region. After all, the Orient is not a place, but rather “an idea that has a history and a tradition of thought, imagery and vocabulary,” as he was continuously at pains to explain (Said 2003: 4). And yet the absence of even an imagined Maghreb in Said’s account of Orientalism – Delacroix’s paintings, Théophile Gautier’s sketches and stories, Malek Alloula’s collection of “harem” postcards – is all the more striking by virtue of the fact that the vast archive he mobilizes, beginning with Napoleon Bonaparte’s 1798 invasion of Egypt and the “takeover of North Africa” that ensued, is in large part a French colonial one, stretching from the Atlantic coast of Africa to the Pacific shores of Indochina (Said 2003: xxii). As wryly noted by an otherwise sympathetic critic, “an Algerian . . . could not possibly have written a study of Orientalism and neglected completely, as Said neglects, the French relation to North Africa” (Musallam 1979: 22). And although Said does not detail what he calls “the dialectical response” to imperialism in Orientalism (2003: 104), anti-colonial writings from France’s colonies, and in particular from the Maghreb – by Frantz Fanon, Albert Memmi, and Abdelkebir Khatibi, among others – have been seminal to the development of the field Said’s work helped launch in the English-speaking world: postcolonial studies.

Said in part redressed this imbalance in his sequel to Orientalism, Culture and Imperialism, a book that supplements his analysis of imperialist representations – including Albert Camus’s Algerian writings – with a renewed focus on “resistance against empire” by the likes of Aimé Césaire, Fanon, and Abdallah Laroui (1993: xii). And yet the Maghreb remains peripheral in Said’s work, symptomatic not only of the vicissitudes of biographical origins and itineraries, but also, as Françoise Lionnet has suggested, of “the long imperial history of conflicting Anglophone and Francophone spheres of political and cultural influence in relation to the Arab civilizations of the Maghreb and the Mashriq” (2011: 399). Said’s Palestinian and Egyptian background, and his location in the English-language academy, partly explain his critical orientation toward the Arab east (al-mashriq). With the exception of Laroui, whom Said cites at several points, and a brief if admiring mention of “the decolonizing literature of the time, whether French or Arab – Germaine Tillion, Kateb Yacine, Fanon, or Genet” at the end of his long analysis of Albert Camus’s Algerian writings, there is little evidence of a sustained engagement with Maghrebi literature and theory in Culture and Imperialism (Said 1993: 185).

It is not our task to fault Said with yet another critical lacuna on empirical grounds. Much ink has been spilt on the absence of the German, Russian, Spanish, etc., empires in Orientalism, despite Said’s explicit insistence that his focus was on methodology rather than exhaustiveness (Said 2003: 4). Our aim, rather, is to imagine what conclusions Said might have drawn had he more fully engaged with Maghrebi anti-colonial literature and theory. What can the Maghreb teach us about Orientalism, and Orientalism? In turn, and equally important, Said’s work continues to ask crucial and difficult questions of Maghreb scholars. In light of his deconstruction of naturalized areas of study, what are the stakes of our ongoing commitment to an area studies model born out of Orientalism and the Cold War era shift to American ascendency? What does the Maghreb, as frame of analysis, enable, and what does it foreclose?

For those of us who work on the Maghreb, one of the most important lessons of Said’s Orientalism is what he called “methodological self-consciousness”: the call to interrogate, denaturalize, and historicize the borders of the regions we study (2003: 326). If Said was not the first to draw attention to the colonial production of areas of study – Mohamed Sahli, Laroui, Mohammad Abed Al-Jabiri, and Khatibi are some of his Maghrebi predecessors – Orientalism has had by far the greatest impact in terms of global reach and academic dissemination, a feature of the unequal translation and distribution of intellectual capital, no doubt, but also of Said’s preternatural capacity to synthesize an encyclopedic amount of scholarship into forceful, and often polemical, argument. Translated into more than thirty languages, Said’s best-known work has become an unavoidable reference for students of the Maghreb, from Colombia to Japan – and this despite the fact that Orientalism overlooks the Maghreb in locating the stretch of European imperialism “from the eastern shores of the Mediterranean to Indochina and Malaysia” (41).

In this dossier, we ask what it would mean to think the Maghreb after Orientalism, forty years after the publication of a work that invites us to denaturalize our disciplinary formations and areas of specialization. “After” is here both a marker of the time that has elapsed since the publication of Said’s watershed book, and an acknowledgment of the debt owed in Maghreb studies to Said. With a nod to Ali Behdad’s 1994 special issue of L’Esprit Créateur, “Orientalism after Orientalism,” we also seek to supplement, expand, and critique some of the tenets of Orientalism. As a number of scholars working in the wake of Said have shown, the Maghreb is in a number of ways exemplary of the colonial condition, from the production of ethno-racial identities in the colonial laboratory (Lorcin 2014, Anidjar 2003, Hochberg 2009) to the occlusion of the colonial past (Stora 2005, Shepard 2006) and the transfer of legal and discursive practices of governmentality from colony to metropole (Hajjat 2012, Le Cour Grandmaison 2010). Since Said’s untimely passing, the Maghreb has come into view in spectacular fashion. In the wake of the mass popular movements ignited in Tunisia in 2010 and the refugee crisis still unfolding before us, how might a renewed focus on the Maghreb allow to us to revisit and update Orientalism? Expanding our focus yet further, what might Said have made of the shift of geopolitical gravity away from Europe and the United States – a shift he already acknowledged in Culture and Imperialism, without elaborating upon its consequences for our understanding of cultural imperialism (1993: 284)? The essays published in this dossier seek to explore the critical role of the Maghreb in understanding, and undermining, the political, military, and epistemic forces that Said bracketed under the term Orientalism.

Said was not the first to expose the imperial workings of what Moroccan poet Adbellatif Laâbi called “colonial science”: the disciplines that make up the field of Orientalism (1967: 3). In her essay, Susan Slyomovics uncovers a rich archive of efforts to decolonize the social sciences in the Maghreb, from official appeals to ban ethnology in Algeria and Pierre Bourdieu’s damning sociology of colonial Algeria, to the playful writings of Habib Tengour and the literary criticism of Khatibi. David Fieni takes up Khatibi’s essays and poetry to offer a Saidian model of “portable theory.” Against the idea that theoretical paradigms originate in a particular place (Europe, say, or the Maghreb), Khatibi’s “transversal intersemiotics” become an invitation to think across colonial cartographies – metropole and colony – without losing sight of the power differential that produced them as discrete sites. This transcolonial methodology animates Olivia C. Harrison’s essay, which turns to Khatibi’s writings on the Maghreb as a “horizon of thinking” and Said’s notion of Palestine as “utopia” to elucidate a neglected dimension of Orientalism: Said’s attachment to decolonization as an ongoing process, one that requires anti-colonial critique in the present.

The next two essays in the dossier take up a medium that is absent from Orientalism, but was nevertheless important to Said: film. Brian T. Edwards tracks the coincidence of American ascendancy and Orientalist representations in Hollywood, starting with the 1942 film Casablanca, which ushers in new forms of Orientalist representation even as it rescripts classic tropes. Madeleine Dobie elaborates on Said’s paradoxical relationship to the Maghreb in her essay on the iconic film of the Algerian revolution, Battle of Algiers. If the Maghreb is absent from Orientalism, Said’s public comments on Gillo Pontecorvo’s film make clear the importance he attached to Algeria as both model of decolonization and admonition against unrestrained nationalism.

Algeria is, in this sense too, a figure for Said’s Palestine, even though he did not locate the separation of the twin figures of the Semite – the Arab and the Jew – in the Maghreb. Reflecting on Hélène Cixous’s and Jacques Derrida’s notion of “the cut” that separates Arab and Jew, Gil Z. Hochberg concludes this dossier by reading the “impossible figure” of the Arab Jew into Orientalism to supplement, and complicate, Said’s critique of colonial discourse.

Written forty years after Said’s field-defining book, the essays in this dossier reflect a deep engagement with his thinking, sketching in broad strokes several areas of research on “the Maghreb after Orientalism.”

Olivia C. Harrison is Associate Professor of French and Comparative Literature at the University of Southern California. She is the author of Transcolonial Maghreb: Imagining Palestine in the Era of Decolonization (2016) and co-editor of Souffles-Anfas: A Critical Anthology from the Moroccan Journal of Culture and Politics (2016). Her manuscript-in-progress, Banlieue Palestine: Indigenous Critique in Postcolonial France, charts the emergence of the Palestinian question in France, from the anti-racist movements of the late 1960s to contemporary art and activism. Her most recent article, forthcoming from diacritics, examines the recuperation of minority discourses by the French far and alt right.

References

Alloula, Malek. 1987. The Colonial Harem. Translated by Myrna Godzich and Vlad Godzich. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Anidjar, Gil. 2003. The Jew, the Arab: A History of the Enemy. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Behdad, Ali. 1994. “Orientalism after Orientalism.” L’Esprit Créateur 34 (2): 3-11.

Gautier, Théophile. (1845) 1973. Voyage pittoresque en Algérie. Geneva: Droz.

Hajjat, Abdellali. 2012. Les frontières de l’“identité nationale”: l’injonction à l’assimilation en France métropolitaine et coloniale. Paris: La Découverte.

Hochberg, Gil. 2007. In Spite of Partition: Jews, Arabs, and the Limits of the Separatist Imagination. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Laâbi, Abdellatif. 1967. “Le gâchis.” Souffles 7-8: 1-14.

Le Cour Grandmaison, Olivier. 2010. De l’indigénat. Anatomie d’un “monstre” juridique: le droit colonial en Algérie et dans l’empire colonial français. Paris: Zones.

Lionnet, Françoise. 2011. “Counterpoint and Double Critique in Edward Said and Abdelkebir Khatibi: A Transcolonial Comparison.” In A Companion to Comparative Literature, edited by Ali Behdad and Dominic Thomas, 388-407. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Musallam, Basim. 1979. “Power and Knowledge.” MERIP Reports 79: 19-26.

Lorcin, Patricia. (1995) 2014. Imperial Identities: Stereotyping, Prejudice and Race in Colonial Algeria. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Said, Edward. 1993. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Knopf.

—. (1978) 2003. Orientalism. New York: Vintage.

Shepard, Todd. 2006. The Invention of Decolonization: The Algerian War and the Remaking of France. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Stora, Benjamin. (1992) 2005. La gangrène et l’oubli: la mémoire de la guerre d’Algérie. Paris: La Découverte.

Leave a Reply