Note on Belarus

Wlad Godzich

Belarus has not figured prominently, if at all, on most anglophone readers’ attention horizon. Things are beginning to change, and Belarus will prove to be interesting geopolitically and even epistemologically.

Belarus is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe, bordered by Russia to the East, Poland to the West, Ukraine to the South, and Lithuania and Latvia to the North. It is roughly the size of Spain but has only nine and a half million inhabitants. Forty percent of the land is covered with forests, including the last primeval forest in Europe, shared with Poland. It owes its name to medieval chroniclers who divided the land invaded by Vaerengians (Eastern Vikings), called Rus’, into Black Rus’, White Rus’ and Red Rus’ (Ruthenia in Latin.) The boundaries of these color-coded lands were not clearly established, nor do we know why these three colors were used. Belarus is the contemporary version of White Rus’.

No country existed under that name in the middle ages, when some of it was ruled by a local dynasty. It was absorbed into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and then into the Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania when the two countries merged. It became an object of contestation between the Grand Duchy of Muscovy and the Commonwealth, with many of the battles between the two fought on its territory. It was eventually absorbed into Muscovy, which took on the name of Russia, with the decline of the Commonwealth. When the Russian Revolution broke out, a Byelorussian Soviet Republic was proclaimed, and this Republic joined the Russian Soviet Federation and the Ukrainian Socialist Republic in the foundation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1921. Much of the war between newly independent Poland and the USSR was fought on Byelorussian territory, and large part of the west of it was awarded to the victorious Poles by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

World War II devastated Byelorussia. Under Hitler’s master plan, all of its land was to be cleared of its inhabitants and then accommodate German settlers in need of Lebensraum. All the cities were levelled to the ground and one third of the population was killed by summary execution, including almost all of the Jews. To this day, mass graves are discovered in the Belarusian forests. Belarus rebuilt its cities during the Cold War and, as a result, has some of the most modern cities in Europe. The capital, Minsk, is particularly well-designed with large avenues, parklands, and an excellent subway system. Belarus became an important industrial producer during this period, with raw materials imported from the rest of the USSR and then resold within it. It became one of the world’s largest manufacturer of heavy agricultural equipment and the foremost producer of tractors.

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic retained a largely Stalinist structure and ethos up to the end of the Soviet Union. The breakup of the Soviet Union was legally effected by the signing of the foundational charter of the Commonwealth of Independent States (C.I.S.) with headquarters in Minsk and a Byelorussian as its head. Belarus, as it now called itself, was ruled by Aleksandr Lukashenko who described himself as an “authoritarian.” He rejected all attempts and calls to liberalize his country. He entered into a prolonged negotiation with President Yeltsin of Russia to define the relations between the two countries. In 1997, with Yeltsin very diminished by alcoholism and illness, a treaty was signed. It stipulated that the two countries would form a “Union State,” have a single joint parliament, one defense and foreign affairs policy, free circulation of citizens, and a single currency. A rather long and sloppy document, it cribbed the European Union treaties, with some echoes of the treaty that created the Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania several centuries earlier. Lukashenko did not hide his ambition to eventually become the President of the Union State, expecting the transition to this position to occur upon Yeltsin’s death. He was taken by surprise by Vladimir Putin’s rise to power. He even went as far as to propose that Putin be Prime Minister of the Union State that he would head. In later years, he claimed it was a joke. What was not a joke was his distrust of Putin.

Putin began to assert his dominance by tightening the screws on Belarus’ economy, raising the price of oil and gas, among other things. During the Soviet period, Byelorussia refined a great deal of Russian oil that it imported as low cost and then resold to Russia at a handsome profit. Putin viewed this arrangement as a subsidy to Belarus and he kept raising the price of the unrefined oil, and thus breaking Belarus’ growth.

Putin’s interest is twofold. The extension of NATO deep into Eastern Europe and the Baltics made him fear what he perceived as a policy of encirclement. It was the prospect of NATO and EU membership for Georgia and Ukraine that led him to wage open war on the former, and semi-covert war on the latter (including the annexation of Crimea). Belarus had to return to its historical role of buffer and glacis between Russia and a hostile West. The largest ever anti-NATO maneuvers were staged on Belarusian territory, and over a hundred thousand Russian troops have stayed in Belarus. Putin has asked Lukashenko openly to give Russia a military base, something that Lukashenko has refused.

Putin’s second interest is personal. By 2024 he will have exhausted his right to stay on as President of Russia legally. For some time now, he has been looking for an escape and he recently proposed amending the Russian Constitution. On the surface, the proposal is surprising: the President would be limited to two terms, whether consecutive or not; his powers would be greatly diminished, with many of them being transferred to a Prime Minister answerable to a greatly reinforced Duma (Parliament). In speeches presenting these proposals, Putin evoked what he called the sad spectacle of the Soviet Union in the eighties when, lacking an orderly mechanism for the transfer of power, it had to go through increasingly ill old leaders waiting for their death. In effect, Putin has coopted the arguments of his opponents. At the same time, he has been holding long and pressing discussions with Lukashenko about the Union State that he now claims must be properly set up. In his view, the Union State, as a new entity, would have to create a new position of Chairman of the Council. In effect, he proposes the return of the Politburo with himself as Chairman for life. Belarusians, including Lukashenko, see this as a step toward the annexation of Belarus within Russia, and his citizens have staged large demonstrations against this prospect. Political demonstrations have been severely repressed by Lukashenko in the past, but these were tolerated, and even surreptitiously encouraged by him. Talks between Putin and Lukashenko have broken down and, by December 31, 2019, Putin cut off oil and gas supplies to Belarus. Their flow has been restored recently when Lukashenko negotiated a makeshift arrangement with Norway (a NATO member.)

Lukashenko understands his predicament well. He may have a hope of staying in power if he is able to establish quickly good relations with the European Union, an organization that has criticized his constant violation of human and civil rights, the rigging of elections, and his maintenance of the death penalty (the last European country to do so), earning him the description of “the last dictator in Europe.” His immediate goal is to show his own population, as well as the European Union, that he has a plan for a viable Belarus independent of Russia. The central element of this plan is drawn from the history of the Varangians, who sailed from the Baltic to the Black Sea (and the Caspian Sea) to trade with, and occasionally raid and sack,

Constantinople and its possessions, and the Arab merchants of what is today Azerbaijan. Lukashenko proposes to enlarge an existing canal in Poland, dredging rivers between

Belarus and central Ukraine and building port facilities on the Black Sea. Belarus has been trading agricultural equipment to Turkey and other nations of the Eastern Mediterranean. It has also developed tourism with the Gulf States, offering mild temperatures and safe surroundings for families during the high-temperature months of the Gulf area. Lukashenko has discussed these plans with the Poles, who seem interested: they are building a Liquid Natural Gas port on the Baltic to bring in American and Norwegian gas, and thus freeing themselves from Russian dependency. He has also held talks with the Ukrainians who are more lukewarm to the idea. Much of the dredging would have to be done in the north of Ukraine in the area of Chernobyl, and the Ukrainian do not see themselves as beneficiaries of the waterway. Lukashenko, with the help of Sweden, has calculated that the canal and river work would cost around six billion Euros, and he has started negotiations with the European Union for this sum. He is aware of the fact that the EU will want action on all the conditions and practices it has condemned. He has not indicated whether he intends to comply with EU demands, stressing instead that he alone can prevent Russian annexation.

The second part of his strategy is to secure the support of his population, a rather daunting task, given his history of repression and his boasts of being an authoritarian. He has released some prisoners as a gesture of good will. His principal tool is to reinvent himself as a Belarusian nationalist and as the leader of a populist movement. On this score, he is falling back on an established historical force in Central and Eastern European history of nation-building: the defense and illustration of the national language.

This is where the epistemological dimension of what may be called, by historical analogy, The Belarus Question emerges on the horizon of attention. Language-grounded arguments for national identity and independence were the products of the German-style national philology that emerged in the eighteenth century and became dominant in the nineteenth. The object of this philology was to identify, describe and purify the “true” language that expressed the “real spirit” of a “people.” These ideas were central to the project of German unification and they animated the Romantic view of language. National philology brought together the resources of historical linguistics and literary studies and fostered nationalism. We may want to recall how French philologists, forced to acknowledge the importance of Germanic tribes such as the Franks in the formation of a country named after this tribe, nonetheless argued that only barbaric elements were inherited from this source and they were offset by the rational and harmonious contribution of Gallo-Romans, apparently evident in the Latin derivation of the language.

Invoking national philology to help create a Belarusian national-populism [no hyphen?] runs quickly into a series of problems: whatever Ruthenian (the preferred designation of philologists) may have been like, its speakers were subjected to forceful acculturation first by the Poles and then by the Russians. The philologists at the universities of Vitebsk and Minsk were trained in German methodology and worked in Russian and saw other “Ruthenian” languages as adjuncts of Russian. We ought to bear in mind that the word ‘ukrainets’ (Ukrainian) designated a nationalist rather than a status. In any case, only one third of the inhabitants of Belarus speak Belarusian at home; the rest speak Russian, with small minorities of Polish, Ukrainian and Lithuanian. Asserting the primacy of Belarusian would require a major effort and many years to succeed.

The major reason that national philology has been retreating is that its foundations have crumbled. These foundations were ontological: there is a language X, there is a spirit X’, there is a people X”, and therefore there is a nation XXX. All of these claims are fictions: their objects have no ontological status. They are constructs of ideologically driven disciplines. It is not surprising that the Poles, who believe they survived the partitions of Poland thanks to their faith in their language and their religion, have supported Belarusian nationalists living in exile in Poland and broadcasting in Belarusian. The revival/invention of Belarusian is not going to save Lukashenko.

What could unite the inhabitants of Belarus is a reflection on the exterminating policies of the Nazis in World War II. Unlike the genocides carried out against Jews and Roma, and the killings of homosexuals, political opponents, and disabled—all of which targeted people because of who they were, that is, on the basis of their ontology— the mass massacres of Belarus were carried out on the basis of where people were. The first, “ontological massacres” were entrusted to the SS; the latter “place-based” genocide to the Sonderkomandos (special units) of the Wehrmacht.

Belarusian, as a language, needs to be described not through an ideal type grammar, but through actual practices and competencies of its speakers. Many areas of the world, from the Middle East to China, would benefit from such an approach. Such areas are inhabited by people who have various levels of competence in the registers and speech genres of more than one ‘language.’ They achieve varying degrees of comprehension and mutual understanding over an area that would best be described through the resources of fuzzy logic rather than clearly delineated maps. Such an approach would bring out the fact that cities are overlaid with many communicational competencies and may well differ from their surroundings.

The subjective dimension of whereness, i.e. hereness, could well be the starting point for building a sense of community and belonging. This starting point already exists: many people in the lands of Rus’ and beyond describe themselves as “tuteyshe,” a word that means “from here.” They do not invoke borders, boundaries, nation states, languages or religions, but the facticity of location, a location defined by a deictic and therefore portable. Deictics do not have coordinates but they do have horizons.

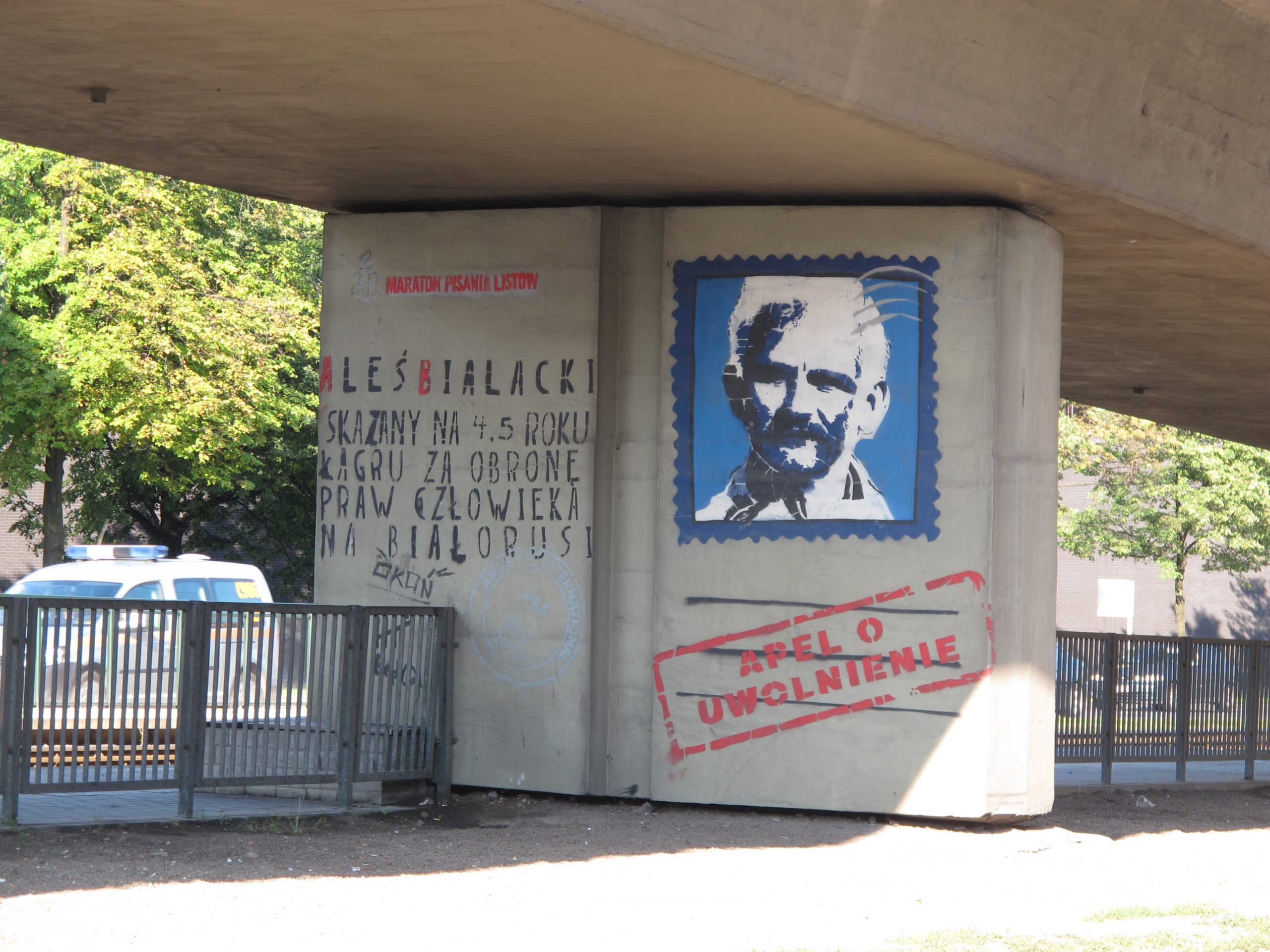

About the Local and What All Hold in Common: Belarusian Human Rights Activist Ales Bialiatski in Conversation with Olga V. Solovieva

This interview took place during the workshop “Cultures of Protest in Contemporary Ukraine, Belarus and Russia” at the Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society at the University of Chicago, 03/01/2019.

Transcribed by Ekaterina Lobanova

Translated by Oliver Okun

Olga V. Solovieva

Ales Bialiatksi was born September 25th, 1962, in Vyartsilya, Sortavalskiy District, Karelia, in the Russian Federation. He is a Belarusian human rights activist, a specialist in literature, and an essayist. In 1965 the Bialiatski family returned to the Svietlagorsk District of the Gomel Region of Belarus. Starting in 1982 Ales Bialiatski began taking part in an illegal national-democratic youth movement. In 1984, he completed his studies as a specialist in teaching Belorussian and Russian language literature at Gomelsk University. In that same year he entered the Institute of Literature at AN BSSR in Minsk as a graduate student. In 1985 through 1986 Bialiatski served in the Russian army and simultaneously continued his graduate studies. He became one of the founders of the informal partnerships of young literary specialists, «Тутэйшыя», and actively participated in communal democratic processes during Perestroika. He was one of the organizers of the large-scale civil act known as «Дзяды», in 1988 in Minsk. He was also one of the founders of the first mass protest by the Belorussian People’s Front. In 1989 Bialiatski was elected as the director of the museum of literature Maksim Bogdanovich, and worked there until 1998. In 1990 he became a deputy of the Minsk city council. Bialiatski managed the Human Rights Center «Вeсна», which was engaged in aiding the victims of political repression. In 1998 Bialiatski began working full-time at «Вeсна». He was arrested in 2011 and held in prison until 2014 for his human rights activities. While in prison he received the first human rights award from the European Union Václav Havel. He was nominated several times for a Nobel Peace Prize, and he is the author of eight books.

Olga Solovieva: Ales, to begin with could you please say a few words about Belarus as a state? Even though it is a large country in the very center of Europe many of our readers don’t know about its existence. It is the classic proverbial elephant in the room. What’s going on here?

Ales Bialiatksi: Not long ago a huge area in the east that stretched from Brest to Kamchatka was considered one country, and there lived the Soviet people. But, for various reasons, the Soviet Union collapsed and the citizens of Europe realized, much to their surprise, that to the east there were not only Russians, but also countries like Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova in Eastern Europe, each with its own people, culture, and history. This was the discovery of the Eastern European Atlantis. Throughout the last two-thousand years Belarusians, either independently or in partnership with neighboring peoples made an effort to preserve, establish, and find themselves. They were heavily influenced by their neighbors, who by the way were also influenced by us, but the Belarusians never lost their own identity. Belarus’s development was not simple, and in some historical processes we developed slowly, but we are definitely not outsiders on the map of Europe. While president Lukashenko says that Belarus is the geographical center of Europe, in reality we live along the eastern outskirts of Europe. But Europe itself is made up of such outskirts. Oslo, Lisbon, Istanbul are all on Europe’s outskirts, just as Minsk is.

The problem is that thanks to the post-Soviet politics of the contemporary Belarusian authorities Belarus has long been a closed country, a reserve or a fragment of the Soviet regime, and a terra incognita for the whole world. It was only in 2018 that the visa system was changed, allowing citizens of the EU and the USA to come to Belarus for one month. That is the beginning of the gradual opening of the country.

Olga Solovieva: The whole world knows you as a human rights advocate, but you were not educated as a sociologist, a political scientist, or a lawyer, but as a philologist, and a specialist in Belarusian literature. How did you go from literature to human rights advocacy? What is the link between literature and human rights?

Ales Bialiatksi: It’s natural. Many journalists, and intellectuals with background in humanities end up working in human rights. I’m no exception. Many of my colleagues involved in human rights were also educated in humanities. Actually, the main reason behind human rights activism can be expressed with the rather banal slogan, “let’s make life a little better for the people around us.” This desire to make life better lies at the foundation of all human rights endeavors. Therein lies the motivation for my work. I have been involved with the civil activism for a long time, since I was a student. Back then, in the Soviet Union of the 1970s and 80s, we had groups that tried to stop the processes of denationalization and russification of Belarus. I took part in such groups. They were national-democratic groups. The various values that we searched for and tried to develop were not just nationalist, but also democratic. This connection had always existed. Not long ago I was looking over the documents that we published in the early 80’s. They express an entire series of democratic demands, including freedom of speech, freedom of information, and equal rights. In the Western world these values were so widely accepted, that they are considered incontestable. At the time these values, along with the vision of an independent and democratic Belarus sounded to us like a revolutionary idea. We saw the ideas of independence and democracy as deeply interconnected.

OS: In Belarus as in many other former Tsarist and then Soviet regions, democracy was understood as the right to national self-determination. But what would guarantee that the national-democratic balance would not turn into nationalism? Consider what happened with such revivals of national consciousness in the post-Soviet Russia and Poland, where the cultivation of national specificity turned into nationalism, chauvinism, and racism. Tatars, Jews, Roma, Russians, and Poles all live in Belarus. Where is their place in the national-democratic model?

AS: Vasil Bykov, the famous Belarusian writer, a contemporary of ours, who was very concerned with the future of the Belarusian people said, “a large nation’s nationalism inevitably leads to chauvinism, while a small nation’s nationalism is firstly directed towards its own survival among other nations.” The government has a huge responsibility to preserve the rights of minorities. But in today’s Belarus paradoxical things are happening. Mentally, Belarus remains a post-colonial country. Belarusian language and culture continue to die out, just as they did in the Soviet Union. The government does not support or promote the Belarusian national identity, as if we were further constructing the common “Soviet People.” But as I advocate for the development of Belarusian culture, I don’t want the rabid nationalism ever to come to power in Belarusian politics. In prison, where I served my sentence, one of the major rules of co-existence was “live and let live.” I consider this to be the golden rule of uttermost importance to us as citizens of Belarus, as well as in all other situations in life.

OS: Was your decision to study the Belarusian language and literature in the context of the russification of Belarus a political decision?

AS: In the beginning, no. I simply wanted to study philology and, above all, Belarusian literature, before we, already as students, came to realize through our experience that the government’s politics was directed towards containment and, in fact, destruction of Belarusian culture and language. The government’s position had an impact on schools and the press (which were generally in Russian), and the study of Belarusian history and culture. The official doctrine was that all peoples would integrate. The official doctrine was about the fusion of all nations. We were taught that all nations will merge into one mythical, large nation of “Soviet citizens.”

OS: And nevertheless, this mythical Soviet nation was being created on the foundation of the Russian language, and not on some language like Esperanto. By the way, this truly international language was outlawed in the Soviet Union. But Russian, of course, was served up to the people in the form of the Soviet ideological cult of personality. Do you remember Mayakovsky’s verse “I would learn Russian for that alone that Lenin spoke it…”?

AS: As students of Belarusian philology we did not like this disregard for our culture. We fought back because we understood that with the implementation of this doctrine there would be no place for our and other cultures. This destruction took place right before our eyes and aroused feelings of protest.

OS: And which language did you grow up speaking?

AS: Russian. My parents lived in Russia for a long time. My father lived there for twenty-five years and my mother for fifteen years. And when they returned to Belarus they came back to an industrialized city, Svetlogorsk, where they could find work in the 60s. Kindergarten through high school were all in Russian. I heard Belarusian from the older generation. My grandmothers spoke only Belarusian. One of them lived in Russia for twenty-five years, but never stopped speaking Belarusian. My other grandmother didn’t speak Russian at all. She lived in Polesie her whole life. When I would go and visit her when I was five and chatter in Russian, they would laugh. Older women of my grandmother’s generation would put me on the chair and ask, “Sashik, say something in Russian,” and they would laugh because they so rarely heard Russian. So I always had this ancestral connection to the Belarusian language. It was hurtful when I started realizing that this all was vanishing. My parents spoke Russian. My mother resumed speaking Belarusian when I changed to Belarusian.

OS: What is the difference between Belarusian and Russian? What are the particularities of the Belarusian language? At Moscow State University we learnt that Belarusian was considered a Russian dialect, and only in 1944 earned its status as a separate language.

AS: That’s complete nonsense. I’ve also read how the state “scholars” of the 19th century wrote about Polish as a Russian dialect. In the medieval state of Belarusians, Lithuanians, and western Ukrainians known as the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Belarusian was the language of the government, and they conducted all state affairs in Belarusian. Belarusian was the first East-Slavic language in which the Bible was printed. And where did the folklorists hide the tens of thousands of folk songs, fairy tales, sayings, legends written in poetic Belarusian? Was this all put in an archive and forgotten?

The particularities of all Slavic languages lie in the fact that we all came from rather similar closely related accents and dialects, but that was so long ago! Many common words were preserved, but often these words have entirely different meanings in our languages. For example, the word, благо (good) is добро (good) in Russian.[1] Полночь (midnight) in Russian, as in the middle of the night, is поўнач in Belarusian, which means “north.” Листопад in Russian entails the process of leaves falling, while in Belarusian лістапад means “November.” [2] “Dog,” “medal,” and “steppe” are all masculine in Belarusian, whereas the same words are feminine in Russian. In Belarusian there is no soft “r” (р) or “shch” (щ), sound, but there are “dz” and “dzh” sounds in Belarusian etc. As far as lexicon is concerned Belarusian is much closer to Ukrainian. We understand each other without translation. Perhaps in Belarusian there aren’t as many sonorous sounds as there are in Romance languages, but it is rather soft and with many aspirations. As for pronunciation, Belarusian is somewhere between Russian and Polish. In Belarusian there are very few Old Church Slavonic words, but there are many ancient Slavic words that were long forgotten in other Slavic languages. I very much love the Belarusian language.

OS: It is interesting that you identify with the Belarusian language of your grandmothers and not with Russian of your parents, the language in which you thought and spoke.

AB: It was a certain process, but there was also a trigger that led to all this. After my second year at the university, during my travels around Belarus to visit historical memorials, I encountered artists who spoke Belarusian. It was the first time I saw people who weren’t paid to speak Belarusian. Cultured people, artists, who painted and spoke Belarusian. I stood there with my mouth agape. One of the artists turned to me and asked in Belarusian, “what’s your name?” I said, “Sasha.” He replied, “No, you aren’t Sasha, you are Ales.” And ever since I have been Ales.

I changed to Belarusian when I was nineteen. At the time it was a provocation. In the beginning all of my peers laughed at me, because they knew me as a Russian speaker. In the Belarusian classes we spoke Belarusian, but after class everyone would instantly switch to Russian. Even my good friend, the poet Anatol Sys, would say, “Just give up! You won’t manage it.” All these guys who studied Belarusian philology, like Sys, were from villages and Belarusian was their mother tongue. They always spoke Belarusian. They studied in Belarusian schools. When they went to university they switched to Russian to be like everyone else, or they spoke Trasianka, a mix of Belarusian and Russian. But just in two months everyone was surprised when I had to speak Russian for one reason or another. I started speaking Belarusian alone after that memorable encounter with the artists, but my friends quickly joined in. We formed a group. In our circle there were first just five or six of us. Two years later, by the time we finished our studies at the university there were already about forty people speaking Belarusian.

By speaking Belarusian my friends and I propagated Belarusian culture. Some professors looked at us askance. Even though Belarusian philology was our official specialization, some professors considered us nationalists. I remember how one professor was outraged and tried to convince me that the future lies in Russian. And what is Belarusian? A return to the past? That was the relationship many had to Belarusian.

OS: Belarusian is connected with the idea of challenging the Soviet regime and protest. What is Russian associated with? After all you grew up speaking Russian.

AB: Russian is, first of all, a huge cultural layer – it represents an understanding of things connected with good and evil, with right and wrong, and all that’s connected with classic Russian literature, as a part of European literature. I’ve read through many of the Russian classics many times. But at the same time there was an understanding that Belarusian literature also exists, is quite developed and offers enough material for building one’s character and for grasping some universal human concepts. One could grow and mature as a person by reading it. A rather rich body of literature written in Belarusian was and still is one of the arguments for the Belarusian language. We have medieval literature and modern Belarusian literature, and such authors as Vasil Bykov, Vladimir Karatkevich, Yanka Bryl, Vyacheslav Adamchik, Ivan Shamiakin among dozens and hundreds of others. Literature is what gives languages the right to exist if not for eternity, then at least for a long life, that’s for sure. For me, the switch to the Belarusian platform of world view was a civilizational, cultural, humanitarian, political decision – everything was connected. At one point after university I completely refrained from reading Russian literature in order to better immerse myself in Belarusian culture. To better understand what Belarusian writers were writing and living I needed to limit myself. It was a professional decision.

OS: In the long run the choice to study Belarusian philology became an act of political dissent. But was Russia and the Russian language, besides being the layer of culture and classics, associated with Soviet ideology?

AB: It was and still is. Russian was an instrument of Soviet ideology, and that is why it is important to Lukashenko. It is an ideological symbol, like a flag or emblem, Soviet street names, death penalty. It’s a full set of symbols that underline the continuity of the Soviet Union in today’s Belarusian regime.

OS: This connection brings to mind an analogy. The poet and film director Pierre Paolo Pasolini, as a young man during the Second World War, started studying and eventually writing poetry in Friulian dialect because he considered the literary Italian language to be compromised by the official structures of the government during fascism. It seems to me that your turning to a different language was done in the same spirit.

AB: That’s not entirely the case, in the sense that I never considered Russian to be “my” language. Belarusian was not an alternative, but a return to my own culture. I quickly realized that opposing this governmental system alone is impossible, and so we started broadening our connections and building a network of likeminded individuals. The artists introduced me to a larger group of students in Minsk who were more focused and active. Our group of students at the university in Gomel joined them. We consciously gathered people who spoke the same language and thought about the same things. We were trying to dig things up from our forbidden Belarusian history and shared it with each other through samizdat (underground publications). The first youth organizations in Minsk were formed in 1978 and 1979. The understanding that we were not alone was very important, and these connections have endured to this day.

OS: How did the authorities react to this?

AB: The KGB quickly became interested in our activities because speaking Belarusian at that time was considered suspicious. In the 1930s there were executions, and there was a merciless fight against the Belarusian underground youth organizations in the 1950s. Everything related to the Belarusian language was considered nationalist. There was even such special term as “bourgeois-nationalist.” There was however also a corpus of Soviet Belarusian writers who were permitted to write in Belarusian. Perhaps some of them were not Soviet, but they didn’t demonstrate their sentiments of opposition. The state allowed for one official part of Soviet Belarusian culture, which was kind of Belarusian ghetto.

OS: And you traveled throughout Belarus in order to study the part of the culture which was not sponsored by the state?

AB: Yes, so I could see the historical sites. For me it was a blind study of Belarus. At the time there were no normal travel guides. It was all considered unnecessary and was being destroyed. From various small articles I gathered information about where certain monuments and historical sites might be, and I created a route for myself. For a month I traveled around Belarus, either by foot or hitchhiking.

OS: It is remarkable to see how culture and politics overlap in your personal and Belarusian history, how this purely cultural interest ultimately triggered your conversion to the political activity.

AB: Yes, during this trip I met these artists who put me in touch with my better organized peers. After a year of contacts with them, I learned about the existence of a political and conspiratorial group with its own structure and rules, whose goal was the independence of Belarus. This was already not a merely cultural goal, nor merely cultural program. They called themselves a political party, but in reality they were just about fifteen people. But they were very motivated. I joined them. We paid membership fees, were buying type writers, and circulating samizdat. We often printed the negatives of photographed banned books. A part of Belarusian literature was banned for one reason or another, and was kept in special archives. Those who had access to them photographed them, and then I brought the negatives to Gomel, where the negatives were printed by red light in bathrooms in the old-fashioned way. We then glued the pages into the covers of permitted Belarusian books and read them like underground literature. This was 1982 to 1984. In 1984 I graduated from the university.

OS: And was the liberation of Belarus understood as liberation from the Soviet regime, or from Russia?

AB: Both. We considered liberation as creation of an independent and democratic state. In the 80s dreams of an independent Belarus were completely fantastical, and moreover, very dangerous. If the KGB caught wind of our activities, the whole thing would have ended very badly. We were lucky; in our group there was not a single informant.

OS: That’s rare.

AB: Yes indeed, but the KGB was all around us, because one of the goals that we set for ourselves was the formation of “informal” groups. Perestroika began in 1985. I served in the army for a year and a half from 1985 to 1986. When I returned in the autumn of 1986 the situation had completely changed. It wasn’t clear what direction we were headed, but there were already various informal groups and discussion clubs. Rather quickly a network of informal groups covered all of Belarus. in 1987, with just one year of development, there were already over one hundred organizations involved in preserving monuments, folklore, historical research, restoration, ecology, and culture. For example, a group of technology students started publishing a magazine “Студэнцкая думка” (Student Thought). And two young writers and I who were part of our underground group called “Liberation,” created an organization of young Belarusian writers that created quite a stir. The group was rather scandalous and quite successful. At first there were seven of us, but after three months we were eighty strong. We practically gathered everybody in our generation who wanted a change.

OS: And what did you do?

AB: It was an explosion of freedom. We traveled around Belarus, listened to lectures, helped with excavations and restorations, took part in ecological protests, and, most importantly, we gathered and discussed our texts, and organized group readings. We called ourselves the Comradeship of Young Literati, “Tuteishye” (Тутэйшые), which in translation means, “those who are from here,” or “locals” (in Russian “тутошние”). Instead of saying that we were Belarusians, we referred to ourselves as simply locals. This meant: “Are we Belarusian? The language is dying out, the culture is in shambles. We are simply locals (tuteyshie), not Belarusians. We’re not yet Belarusians.” At the time that name was also a challenge to others.

OS: Locals? This name was meant critically to emphasize the lack of identification with the Soviet State on the one hand, and the lack of Belarusian national identity, on the other.

AB: Yes, locals… One of our goals was to strike the bell and to awaken a sense of national self-consciousness among Belarusians. We met practically every week and discussed what we could accomplish together, what kind of burning questions we had, the questions that we needed to turn our attention to. That was really important because we didn’t have sufficient education in a political sense, and we didn’t have enough new ideas. The youth organization gave us the opportunity to discuss, create, and publish. Then for the first time we openly proclaimed that we had our own coat of arms, our own non-Soviet flag, and that we had our own rather rich history that was withheld from us.

OS: Since your “Belarusian platform” was not merely about language, but also about a worldview and civil stance, I would like to ask you about the concrete topics you were interested in as a literary scholar.

AB: As a specialist in literature, I published several articles about the banned poetry, several dozen poems by the Belarusian classic Yanka Kupala. For the first time in many years, I analyzed the works of Belarusian writers and social activists whose names had been erased from the history of the cultural and political life of Belarus.

OS: Why did they ban Yanka Kupala’s poetry?

AB: Because it was anti-Soviet. In 1918 he wanted an independent Belarus. He was very wary of the arrival of the Bolsheviks. When the Bolsheviks were not there he wrote the marching hymns for the Belarusian army. Yanka Kupala wrote also other poems which were banned for touching on this national problematic.

OS: I would like to ask you about the Perestroika period. What did Perestroika mean for Belarus? How was all this political activity connected with Perestroika? Was it Perestroika that make this all possible?

AB: Yes. All of our activity became possible within the framework of Perestroika, but it seemed to me that we went a step ahead. The generation before us, born right after the war, were also rather active. But they fell under repressions. When the so-called nationalist groups were discovered in the 70s, some of the activists were fired from work, others were removed from their studies, and they even revoked some scholar’s PhD. It also affected artists and historians. Some were permitted to publish and put on exhibitions, but some were prevented from doing the same. Therefore, there were significantly less activists left from that generation, and psychologically they were impeded by their previous negative experience. In the 1960s and 1970s they were in deep defense and constantly under surveillance. When Perestroika began in the mid-1980s they were very wary, and did not believe it was truly happening. Based on their life experience it was not clear to them where this was all going. As for us, well we weren’t afraid and flew forward, and we tried as best as we could to accomplish and seize this opportunity … Although it wasn’t clear to us either how it would all end. Would they arrest us? Would they stop us, or not? In 1987 and 1988 the situation was still very uncertain. For example, they were expelling me from my graduate program. There was a big meeting at the Belarusian Academy of Sciences where I was a graduate student, and the scholar and writer Ivan Naumenko figuratively said, “I can’t understand how one graduate student could screw up two members of the Academy and eight professors!”

OS: Why?

AB: Because in 1988 I was among the organizers of the demonstration called Dzyady (Дзяды), and was detained, brought before a judge, and fined.

OS: What kind of demonstration was it? Can you explain what Dzyady means, and where you got the idea?

AB: The word signifies the traditional commemoration of our dead ancestors. It’s an ancient holiday of sorts that we have for the departed loved ones in our region, in Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine, and Belarus. In the 19th century Adam Mickiewicz who was from Novogrudok wrote an entire poem called Dzyady. Evocation of this holiday was one of the ways we used to show the terrifying results of Stalin’s repressions. We first organized a demonstration in 1987. It was fifty years after the mass repressions of 1937, and we demonstrated without state permission. We did however apply for authorization beforehand, but the authorities didn’t even respond. Unexpectedly two hundred people showed up. It was one of the first of those kinds of actions that started to happen in Minsk after a long period of time when nothing was happening.

OS: How did you get the word out?

AB: Well, by word of mouth between informal organizations, writers, artists, and among those who were hooked by the idea, a lot of people who heard about it joined in.

OS: You protested the Stalin era repressions by using a traditional holiday. How did the authorities react to your activities?

AB: Yes. It was, of course, unexpected. The authorities had to outlaw the holiday. Even though we didn’t officially celebrate it in the Soviet Belarus, it still wasn’t explicitly forbidden in the Soviet times. The authorities did not know how to react. They ended up in a very uncomfortable position. We gathered in the center of Minsk at the monument to Yanka Kupala, and we read the names of the poets who were shot on October 30th, 1937, some writers spoke, one of our older friends sang a song. Our guys from “Tuteishye” read poetry. It all turned out quite beautifully.

The next year in 1988 when we started organizing Dzyady, the authorities did not permit our demonstration. We had a month-long fight with the authorities where they tried to somehow prohibit and smear our actions. They formed a security detachment in charge of protecting the monuments in order to control us, and it didn’t work, but in the end they managed to prohibit us. I was one of the organizers along with the poet Anatoly Sys, who also applied for permission for the demonstration. They summoned us to the prosecutor’s office, and officially warned us that we would be held responsible for the possible mass disorder to come. It really felt like they could just imprison us at any moment, provoke some kind of disorder, and that would be it. We put up the announcements all around the city. We secretly printed twelve thousand little invitations somewhere in the institute of physics, where they printed drafts. We had friends there. But the authorities made the mistake of announcing on the radio that our demonstration was prohibited. This is how it became well known from that moment on. As a result, much to our surprise, in 1988 thousands of people came to celebrate Dzyady. The year before, in 1987, only two-hundred people came, but in 1988 ten to twelve thousand people showed up.

OS: That was already after they opened the NKVD execution site in Kurapaty? [3]

AB: Yes, that happened soon thereafter. Information about Kurapaty was made public in the summer of 1988. The information was already gathered and prepared a year before. Zenon Poznyak, the man who had been investigating this issue, did not reveal the truth about Kurapaty earlier because he was afraid that all the evidence could be destroyed. He gathered testimony from eye-witnesses from neighboring villages. He gathered material evidence from the digs of the “shadow” diggers, who were probably looking for gold in the mass graves. There were bones along with the rotting clothes of the executed scattered about. But most importantly, his article about Kurapaty was based on the memories of the people who were young at the time, or even young children, and who saw all this with their own eyes. The area was surrounded by tall fences, but children climbed over it, hunting for berries or mushrooms. They would witness the executions, but didn’t speak of it their entire lives. People who lived nearby would hear the gunfire from the executions, and some of them even had family members in the NKVD who took part in the killings. Poznyak gathered dozens of pieces of living evidence and held on to it in absolute secrecy, and once the opportunity arose and the newspaper “Literature and Art” started publishing bolder things during Perestroika, such as banned poetry and information about the repression of writers, he arranged with the editor to publish his materials… When they published his article it was, of course, an explosion.

OS: It was one of the very first revelations about the execution sites, right?

AB: At the same time there were findings in Ukraine and Katyn. And it became very topical. But for us it was, of course, the place of foremost significance because the scale of it was enormous. Tens of thousands of people were executed there.

OS: Did you learn about this from the newspaper?

AB: Yes, and that newspaper had an edition of twenty or thirty thousand copies, which is pretty large for Belarus. Peole read it to pieces. It was a bestseller, and that information of course significantly changed society. The truth about these mass executions resonated with people in a powerful way. Initially, we didn’t plan to lead the demonstration Dzyady of 1988 to Kurapaty. We gathered at the Moscow Cemetery, where famous Belarusian poets and artists were buried, but the militia dispersed the demonstration with batons and tear gas, and detained dozens of people, including me. It felt like a catastrophe to me, we didn’t even get to hold our rally. However, people organized themselves and divided themselves up; and then one group went to Kurapaty and another group of a few thousand people went to an open field on a hill and held the rally there. There were so many people that militia didn’t know what to do with them.

The community’s reaction was completely different from what the authorities expected. The dispersion of the rally caused intense indignation and anger, and from that moment one a democratic movement began rapidly developing, quickly becoming a social and political movement that had as its goal the removal of the communists from power. By not admitting their crimes the authorities were in fact confirming that they were the successors of the Stalinist ideological foundations of the 1930s. This was a punch in the government’s gut. Plus, at the time the economic situation was so bad that people had nothing to eat. That combined with the state’s desire to cover up the Chernobyl catastrophe, and our efforts to reveal the true picture of what happened there caused everything to evolve very quickly. This all lead to the signing of the 1991 Belovezha Accords. In 1990 the first elections were held, and a few democratic deputies entered the Supreme Soviet. It was a small group, but they were very active. They managed to force the Supreme Soviet to implement democratic reforms in 1990 and 1991. With the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 Belarus at last became an independent state.

This all happened right before our eyes. If in 1987 we were an underground organization, four years later in 1991 the Soviet Union collapsed, and I became a deputy of the Minsk City Council, I was twenty-nine years old. We had real opportunities to influence the general situation of our country at various levels.

OS: You became known in connection with Kurapaty and through the organization of these demonstrations?

AB: Well, in narrow circles.

OS: Clearly the circles weren’t that narrow if you were elected for city council…

AB: No, it wasn’t because of Kurapaty. First, they elected me as director of the Literary Museum of Maksim Bogdanovich, who was a classic Belarusian writer, and a modernist. People knew me as the director of the museum, of course, because earlier I worked at the Museum of Belarusian Literary History. There was an election campaign throughout the Soviet Union. Directors were elected at all institutions and levels, directors of factories, businesses, collective farms, etc., and so they happened to select me as the director of the museum.

OS: Did you have to stop your graduate studies then? Or did you complete them?

AB: In 1989 I completed my graduate course work and wrote a dissertation, but I did not defend it, because I became the director of the museum. I ran for municipal elections as part of the Belarusian People’s Front, which was a social movement for Perestroika, and as the director of the museum. The Belarusian People’s Front was a proto-party, we can’t even call it a party because it contained people with many different political views, but it was a large democratic movement. We actively advocated for our campaign, and people believed us and voted. I was, however, very young, but that’s what it was like back then.

OS: I am interested in your experience with official state institutions such as the university, academy, and the museum… On the one hand we have these governmental institutions and on the other hand we have your informal cultural-political activism. How did the two coincide? Did they allow you to do all that within these state-sponsored organizations?

AB: Well, at the university they didn’t come around to expel us by the time we graduated. The KGB did however show up right after our graduation in 1984, but they were too late. They were trying to kick me out of the graduate program at the Academy. But two weeks after they said in a general meeting, “that’s it, you’re expelled!” I went to the director to pick up my documents and he said to me, “just go on working, Ales, go on working.” They played as if they were expelling a black sheep for the Academy’s party committee and for the KGB, but in fact they were protecting me. I was lucky. But the minister of culture didn’t touch me at the museum. I looked at the museum as a platform for realization of my initiatives and ideas.

The museum is in the center of the city, a great location. And everybody was gathering there, and all kinds of things were done there. Uniates gathered there, along with Christian democrats, democrats, youth organizations, the Belarusian People’s Front, and worker movements, and they even held various kinds of concerts there. In the early years the first independent democratic Belarusian newspapers, “Svoboda” (Freedom) and “Nasha Niva” (Our Pasture), worked there. I allowed all the democratic groups and initiatives to use the museum’s address for legal purposes. Several dozens of NGOs were registered in a small room of just eight square meters. The minister of culture did not bother us. The major thing for them was that we did our work in a professional manner. And we worked well, because I had a young collective that was prepared, educated, and motivated to work hard. We opened new branches of the museum, and installed new expositions and exhibitions. We worked really hard, and others took us as their model. We even did an exposition at the museum of Maksim Bogdanovich in Yaroslavl, where the Bogdanovich family lived at the beginning of the 20th century.

OS: How did you go from that type of activity to human rights? And why in 1996? At that time you created a human rights center, what was the reason for doing that?

AB: Already back in 1988 we organized “The Martyrologue of Belarus,” it was an organization dedicated to memorializing the Stalin era repressions. We were collecting information about the repressions. One of the problems our organization was addressing was the question of how to memorialize Kurapaty, and so gathering information, preserving the memory of the repressions, finding survivors and helping them has been part of my work since 1988. Then when I became a deputy of the City Council I joined the city commission for the rehabilitation of the victims of political repressions. We worked on the rehabilitation of the people who, for various reasons, haven’t been rehabilitated yet.

OS: Did you have access to KGB documents?

AB: Yes, the access to the documents of the victims was guaranteed by the format of our work. If there was an official request from people, then KGB would give us information about that person, and we would make decision about rehabilitation, and the decision would become legal.

OS: And now that committee probably doesn’t exist?

AB: No, that committee has been disbanded as soon as Lukashenko took power. Everything was dissolved.

OS: But the committee had worked for several years?

AB: Yes, yes. And while I was a deputy, this all was interesting and important to me, and I took part in it all, but…

OS: 1996?

AB: Lukashenko rose to power in 1994…

OS: And you created a human rights center in 1996?

AB: Yes, he came to power in 1994, and the repressions began. After the first crackdown on demonstrations in 1988, they practically ceased to combat the demonstrations. There were some clashes with the authorities, for example in 1990 there were an anti-communist demonstration. They opened a criminal case about that demonstration, but they still didn’t disperse it. The first demonstration that they actually dispersed in 1996 was a march called the Chernobyl Way (in Belarusian, Чарнoбыльскі шлях), dedicated to the problem of recovery from the atomic disaster in Chernobyl. These marches took place annually since 1989, when the Belarusian People’s Front raised the Chernobyl issue, and showed that tens of thousands of people were still living on contaminated land, where they shouldn’t have been living. The government was concealing this information, and when these facts were made public it really angered people, and so in 1990-1991 the government was forced to relocate those living on polluted land. From that moment on, the Chernobyl Way march became a tradition, and we held it every year to memorialize the catastrophe in Chernobyl. In 1996 the protest took on an anti-Lukashenko character. About forty-thousand people gathered, which is a pretty large crowd for Minsk, and they mercilessly dispersed it. And yet again we found ourselves in the same situation as we were in 1988. We organized a quick response team to gather information about people who were arrested because they would hide them, and no one knew where they were held. Generally, people were imprisoned on administrative charges, two organizers were imprisoned on criminal charges.

OS: And what were these charges?

AB: Public disturbance. “Public disturbance” was a provision of both administrative and criminal law. I attended a few of these legal proceedings as a witness.

OS: Not long ago Arseny Roginsky, the late director of “The Memorial,” spoke of the direct connection between the historical research and political activism, and about a connection between the collection of facts about the crimes the government committed against its citizens and the fight for a different democratic form of government that respects and defends human rights. This is exactly the connection I see here, the connections between recognizing the rights of those killed in Kurapaty and the political activism recognizing the rights of the living citizens and your human rights work for acknowledging the victims of historical and of contemporary crimes of the government. What was your experience in this human rights organization in 1996? How long has it been around?

AB: We have been around for twenty-two years. We started to develop it as a public initiative with practically no money at all. We worked for two years as volunteers as we looked for money. I just grabbed a plastic bag and walked around rallies, and people would toss me “bunnies” (money) – that’s what we called Belarusian currency because some animals were printed on it. Bags because of the inflation money was cheap. We would give out this money to the families of the victims of political repressions, because ever since 1996 there was essentially never a time where there were no political prisoners. And that’s how the bitter opposition between civil society and government began, and it continues to this day.

OS: And the government didn’t object to the existence of this organization?

AB: It was an informal initiative. At first, in 1997, we registered as a city center. It was possible back then. I still worked as the museum director then, and was detained for the first time in 1997 for 24 hours. Several months after I was released, they summoned me to the ministry and said, “Choose; either you continue your political activities, or you are the director, because we’re being strangled from above.

OS: And for what reason did they detain you?

AB: Because we picketed and protested against detaining the activists. They detained me for 24 hours pretty often, or fined me. There were literally dozens of people being detained. I was younger then, and I was eager to fight. The years 1997, 98, 99 and 2000 were very rich in activism.

OS: Those were very liberal years in Russia.

AB: Those were terrible years for us. We were losing one position after another, and it all went along with the tightening of laws. They created even harsher laws regarding public activism, dissemination of information, and public organizations. The first re-registration process began in 1999. But still we continued developing as an organization, because there was such public …

OS: … support …

AB: Need, I would say. We simply saw that our work was needed.

OS: And did you accomplish anything? Did you see any results? Did they release anyone?

AB: Yes, yes, we even had the opportunity to participate in the legal criminal proceedings as public defenders. But then they forbade us to act in this role. We participated in proceedings, we connected with the defense lawyers, and searched for help for the victims of political repression. In 1998 I definitively left the museum and started to work professionally at the Human Rights Center “Viasna” (Spring). We constantly had problems with the authorities. They searched our offices, confiscated our first computers, and oppressed us in various other ways. But the group of people that had gathered around me were truly brave.

OS: And how did you financially support this organization? Through donations?

AB: We received our first grant in 1998. And from then on we searched for legal grant opportunities, whichever we could find. At first it was legal, but eventually the government closed everything and created laws making it impossible. No human rights organization has received a single legal grant since 2000. All of that help is called “humanitarian aid” and it passes through the Office of Presidential Affairs, and nobody ever gets anything. Neither the Helsinki Committee, nor journalist organizations, human rights organizations, nor us for that matter, have received any type of official support.

OS: Are there many human rights organizations in Belarus?

AB: There are quite a few because there is a need for such organizations. In spite of the fact that the government is constantly trying to limit us, there are people who take the risk and continue their work, thank God. I’m not just talking about people in our organization, there are others too. Generally, in the last few years young volunteers have become more and more numerous. For a long time there had been a problem that young people simply didn’t show up. They preferred to get involved with political youth organizations, but now they volunteer for various human rights organizations, and that is really good. This is not political activity, but all the same it is activism and what they are doing is real and effective, and people see that.

OS: And you were the leader of “Viasna”?

AB: Yes, I am still the chair of this organization. We have a council and regional branches. We are active in sixteen cities all over Belarus. We are always looking for support not just in Minsk, but also in every region in Belarus. That fact is important to us because it gives us the opportunity to gather information about human rights violations, and to monitor elections all throughout the country. We work closely with other human rights organizations. The Belarusian Helsinski Committee has branches in various cities. Then PEN International and the Belarusian Association of Journalists defend the freedom of the press and free speech, along with directly defending journalists themselves. We also work in tandem with other human rights organizations who might not be as strong as we are, but nevertheless are quite active. All of this is important for the creation of an environment that is conducive to human rights. It is easier to kill one single organization, but our statements regarding political prisoners are usually signed by ten to twelve different organizations. When many different human rights organizations all declare someone a political prisoner it is very difficult to refuse such declaration. Working together is crucial for us, and life simply forced us to stick together, and for the time being that is how we carry on.

OS: What lead to your arrest specifically, … if I may ask?

AB: Of course. In 2003-2004 the government purged the sector of nongovernment organizations, just as they did in Russia in 2012. In Russia they called them, “foreign agents,” here they withdrew various organizations’ registration and effectively liquidated them. They conducted a concentrated campaign. With the decision of the Supreme Court they eliminated the registration of about three-hundred nongovernmental organizations. And we were affected by this purge. They took away our registration in 2003. As a result, we were yet again an informal organization. For me, psychologically, it was not a catastrophe, because back in the 80s I had experience with exactly the same situation. Back then there was no registration and everything was done de facto.

OS: Under what pretext did they close your organization?

AB: They used a rather formal pretext. The government found fault with us for allegedly breaking law as we observed the elections in 2001. Two years went by, and then they took away our registration. We turned to the United Nations Committee on Human Rights. The Committee found the Belarusian Court’s decision to be unfounded. They requested that the Belarusian government renew our registration, but the government, of course, did nothing. They simply ignored the U.N. Committee and their request regarding our registration. In 2006 the Belarusian authorities criminalized activities organized by unregistered organizations, and things suddenly became really dangerous.

They started to investigate mainly young activists, those involved in informal youth organizations and groups. They still considered whether to harass us or not, but for the time being they didn’t. In 2007-2008 a particularly strong wave of propaganda against us came out in all the government owned means of information, including television, practically implicating us as enemies of the ruling power. But at that same time, in 2007, the government began flirting with the European Union, and Lukashenko was required to release all political prisoners, and so they left us alone as well.

This is how it went on until the presidential elections of 2010 which ended up in a crackdown on all oppositional parties, and many people were imprisoned. Dozens of criminal proceedings were held against political activists, and in the midst of that mess they did not forget about human rights organizations and set their sights on our organization. The problem was that the financial grants were transferred to our accounts in Poland and Lithuania, and we reported directly to these foreign grant giving foundations and organizations. The KGB gathered information on the accounts that belonged to me and to the deputy director of our organization, Valentine Stefanovich, and the Belarusian Ministry of Justice appealed to the governments of Poland and Lithuania. In Poland the General Prosecutor’s Office dealt with this issue, and in Lithuania the Minister of Justice was responsible for doing the same. The Department of Financial Investigations, responsible for conducting the formal review, ended up receiving this information because there was an agreement between these governments about the information exchange in the struggle against corruption. But it was clear that on the Belarusian site, the KGB was behind the Ministry’s audition request.

OS: I heard that the Polish government later apologized for this.

AB: As did the Lithuanian government. They didn’t think that their bureaucratic system under the auspices of the fight against corruption would give up financial information about human rights defenders and their organizations. It was a shock for them too, at least in a political sense. They made an official apology to my wife because I was already in prison.

OS: And what were the accusations against you?

AB: Tax evasion, because the money that went to the organization passed through my personal account and through the account of my deputy. Well, at least what they found. The sum found in Valentin Stefanovich’s account was not large enough to constitute a criminal offense. They punished him through an administrative procedure, whereas the sum in my account was larger. They seized all of our grants and the total sum was large enough to incur a criminal offense for tax evasion. However, before the trial they gave me the opportunity to escape.

OS: Escape, you mean emigrate?

AB: Yes, they just wanted me to leave. Then they would be able to say that this so-called human rights advocate is actually a vicious criminal, who doesn’t pay taxes, and that’s why he left the country. That is how they wanted to compromise my reputation and the reputation of Viasna, and of all human rights organizations. They waited for a month and a half but I didn’t go anywhere. I didn’t do anything on purpose, because I knew that there would be no way to defend my reputation from abroad. No matter what, you’re guilty, if you ran away. I was happy with the court hearing because it came out that this was all a KGB operation. The financial review at the core of the process was indeed requested by the KGB. The information and the xerocopied documents, their argument was based on, were obtained illegally. We didn’t know that! And the KGB documents were all part of the trial. They showed the documents to me and throughout the trial I had been reading them. The documents demonstrated that the head of the KGB wrote to the state inspection agency: “I am requesting permission to review the computers that were confiscated from the “Viasna” offices. Perhaps you would find information about Bialiatksi and Stefanovich that would serve as the foundation for criminal charges against them.” There were such documents in our case. Everyone was in shock. The trial made it clear that there was a meeting between two KGB officers and a prosecutor where they discussed tactics concerning the review of our accounts. All of this information came to light during the trial, as did the documents proving that money from the Dutch government and from our Swedish partners was given in support of our organization’s activities. Still they considered the money to be part of my personal income, even though on the eve of the trial the Dutch government sent an official letter where they confirmed that they received complete records on how the funds were spent, and had no complaints against us. It also became clear during the trial that the majority of the grant was spent in Lithuania.

By sending me to prison the government and the KGB thought that they were sending a message to the entire human rights community in Belarus – look, the same will happen to you if you continue. At that time we were very active because dozens of people were sitting in jail. We were crying out in their support at the top of our lungs, appealing to international organizations such as the OSCE, the European Council (even though we are not the members of the European Council), and the European Union, to do something to get our government to release political prisoners.

OS: Did you return to your literary activities in prison? You published your first book after graduation, and there was a kind of break, or did you continue to write throughout that period?

AB: There was a while when I stopped writing at all. It felt irrelevant, as if the printed word’s time had passed. Nevertheless in 2006 I published a book Пробежки по берегу Женевского озера (Jogging Along the Shore of Lake Geneva), a collection of essays about human rights work, observations, and various travels – so I was still writing. After ending up in prison I suddenly had the time that I didn’t have before … However, paradoxically, I actually didn’t have much time there at all.

OS: Imprisoning intelligentsia is dangerous because in prison they start writing … Think of Gramsci…

AB: If they give them that kind of opportunity, or at least don’t bother them … I was writing and sending off what I wrote in letters, although all letters had to pass through a censoring process, and was sent out with a stamp “checked,” or returned.

OS: So you wrote in the form of letters?

AB: Those were letters that I wrote to my colleagues. Two topics were taboo: anything about Lukashenko, or about the prison location, which at first was the pre-trial detention center and then a penal colony. But we were allowed to write, for example, memoires. I practically wrote an entire book-length essay about the troubled period of 2010 before I was imprisoned, more precisely before August 2011. The book was called Ртутное серебро жизни (The Silver Mercury of Life). There was not much there about Lukashenko. If I wrote about him I would mask it by either writing “he” or something similarly ambiguous. I depicted those troubled months, and each moment connected with their efforts to force me out of Belarus, and everything about the arrests, and the crackdowns on demonstrations during elections. I depicted it all in detail. The searches were endless. They searched our offices three times after the elections. They immediately ripped all of our computers right out of our offices the first night after the elections. A month later they raided our offices again. We were on the ground floor, so my colleagues took their laptops and jumped out the windows in a neighboring kitchen. They evacuated. Valentine Stefanovich and I opened the doors together. Much to the surprise of the KBG agents they found an empty room. Afterwards they summoned me to the Attorney General’s office and gave me a warning. Then they searched us again. I was in Vilnius when they searched us that time. I wildly screamed on the phone, “Don’t let them in!” When my colleagues gave phone to a militia man I yelled at him, so he started apologizing, “oh well, they sent us here…” Strange.

OS: So being imprisoned gave you time to document all this history.

AB: Yes, and support of my colleagues…

OS: During your time in prison did your organization continue its work?

AB: Yes, and this was the strongest moral support for me, because the government’s goal was to destroy our organization, and they failed to do that. The organization remained, and no one left. Everyone continued to work even though they confiscated our office space. The office was registered under my name as personal property, and so they confiscated the apartment. This was a huge challenge for us. We did not know if the organization would survive or not. I did my best to support them through my letters. I would tell them that I was fine. “You guys keep doing your job, and I’ll keep doing mine – sitting in jail.” All that I wrote in prison can be divided into two parts: everything that I wanted to say about literature, because during that time my desire to write about literature came back, and the other part is made up of memories and essays about what was going on in the country. These were memories about the 80’s and 90’s. There I recorded everything that I’m telling you now.

OS: It is considered that you introduced the term “Belarusian prison literature”?

AB: I don’t know if I introduced it or not, however I did write about our poets Vladimir Negliaev’s and Aleksandr Feduta’s first books; they were arrested in December of 2010. They wrote their first books in prison, and when I was imprisoned they sent me their books. I received them and wrote a short essay about them, and recalled that in the past other Belarusian writers wrote from prison as far back as in the Tsarist times, not to mention those who wrote from prison under Stalin between the 30’s and the 50’s.

OS: So Lukashenko, so to say, revitalized this literary genre …

AB: In that essay I first used the expression “Belarusian prison literature,” and it took on. After that other political activists who had been imprisoned published their memoires. We then started publishing an entire series of Belarusian prison literature. Six books came out, all written by former political prisoners. We started this literary process.

OS: It is interesting how in your story the development of literature directly intersects with politics, and how in response to politics new genres appear or reappear, just as the genre of “martyrologue” appeared after the discovery of Kurapaty, and how this genre of prison literature came to be…

AB: That’s not new. A rather large corpus of similar literature exists in Russia, not to mention the books written by Andrey Marchenko, Vladimir Bukovski, Pyotr Grigorenko, and the memoirs of Andrey Sakharov, along with other political prisoners such as Eduard Kuznetsov, and Yuri Orlov among others. They left behind very powerful books that became part of the canon. They aren’t just any ordinary notes. They have been a source of amazement for me for a lont time. I wanted that we also have something similar in order to record what is happening right now, because right now in Belarus this period of political persecutions is not over – it continues. It is vital that this remains in people’s cultural memory.

OS: You found a kindred spirit in the literature of Russian political dissidents.

AB: Yes, and not only in Russia. I admired the collection of poetry called Песня прощания (Farewell Song), written by the former Turkmen minister of foreign affairs Batyr Berdiev who was imprisoned in 2002 by the Turkmen government; he then simply disappeared. But he managed to prepare a small collection of poems which by some miracle made it out of the Turkmen prison and was released in Russia. Aesthetically speaking the poems are not strong, Russian, after all, is not his native tongue, and he wrote there under whatever conditions, but this is definitely a literary testament to the hundreds, if not thousands, of political prisoners in Turkmenistan. Almost twenty years went by and still no one knows Batyr Berdiev’s fate; we do not know if he’s alive or dead, imprisoned or free. These things concern our entire post-Soviet community.

And my Georgian friends. Levan Berdzenishvili, a politician and social activist, wrote his memoirs about the 1980’s. He still managed to experience that period before they imprisoned him for three years. Not long ago, he wrote his memoirs about the 1980’s, and his prison entitled Святая мгла: последние дни ГУЛАГa (The Sacred Darkness: The Final Days of the GULAG). This tradition comes from the severe realities of our lives, starting in the Soviet Union, and then under post-Soviet regimes where a confrontation between civil society and authorities continues to this day.

During my time in prison I wrote, and wrote, and wrote. Some of what I wrote was published while I was still in prison. Some of it is still coming out now, because my goal was to write at least one page a day. While in prison I worked in a garment factory as a packer, and that took up most of my time. Whether you liked it or not you had to work for eight hours in addition to inspections. We had one day off, Sunday, one day to pull yourself back together. On Sundays there was always something to fix, or clean, or what-have-you. There was almost no free time. I adapted, and had about one or two hours a day, sometimes three, where I responded to letters and managed to write my one page a day.

OS: Three-hundred and sixty-five pages a year.

AB: Yes, each year, and I spent almost three years there, so I wrote quite a few pages. That kind of thing doesn’t happen when you’re free.

OS: It is ironic that your imprisonment not only gave you time to record all of this, but also drew international attention to human rights in Belarus, and to you personally, resulting in you becoming well known throughout the world in addition to receiving many international awards.

AB: These awards were sent rather as “black spots” to the Belarusian government: “You should do something! You should release political prisoners, and not just Bialiatski, but others too…” These awards were acts of solidarity and pressure on the Belarusian government. I understood perfectly well that the prize wasn’t as much for me as it was a tool to draw attention to human rights issues in Belarus. The same thing happened with Oyub Titiev in Chechnya. In 2018 he received the Václav Havel Human Rights Prize from Europe, and I received the same award earlier in 2013. I was its first laureate. After me my good friend from Azerbaijan Anar Mammadli won the prize. He was involved in monitoring elections and he too spent time in prison. In 2017, before Oyub, the Turkish lawyer Murat Arslan was awarded the prize, who is in prison now. It is a sad prize to win… It turns out that they only give this award to prisoners and those who have seriously suffered….