This response was published as part of the b2o review‘s “Finance and Fiction” dossier.

Matthew Potolsky–Decadent Style for Critical Finance Scholars: A Response to Signe Leth Gammelgaard

Signe Leth Gammelgaard’s “Flowers Without Meaning: Literary Decadence as Finance Aesthetics” rides a wave of work from the last twenty years or so that draws upon the longue durée history of capitalism to contextualize cultural production in innovatively materialist terms. Broadening its vision from the durable leftist influences of the Frankfurt School, Pierre Bourdieu, and Louis Althusser, as well as the deconstructive New Economic Criticism of the 1990s, this scholarship supplements questions of commodity culture, symbolic capital, ideology, and the nature of value with attention to global trade and conquest, modes of production, and the history of economic crises, often drawing on world-systems theory and theories of uneven and combined development as well. One keynote of this turn is the concept of financialization—perhaps most closely associated with the work of the economic historian Giovanni Arrighi—which directs special attention to the power of the financial industry and finance as such in the culture at large.

The most impressive recent work on financialization has tended to focus on literature of the 1980s and after, a period in which finance capital grew in power and influence at a historically unprecedented rate. But Arrighi, drawing on the longue durée studies of global capitalism by Fernand Braudel, sees financialization as recurrent feature of capitalist development, and therefore as one that has marked earlier periods as well. In her essay, Gammelgaard notes that the European fin de siècle was just such a moment and proposes that we can gain insight into the decadent aesthetic of the 1880s and 1890s by seeing it as manifestly a product of the financialized age. This is a claim with which I agree, and which I have been exploring in different terms in my current book project. In this response, I want to highlight the value of the approach Gammelgaard sketches in her essay and reframe her argument in ways that, to my mind, even better comport with how late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century writers understood both decadence and finance capital. My largest claim will be that Gammelgaard’s account of decadent aesthetics should also be applied to the conceptual history of finance capitalism. Scholars of financialization can learn as much from decadence as scholars of decadence can learn from the literature on financialization.

Let me begin by briefly summarizing Arrighi’s argument to highlight the importance of the fin de siècle to his conception of financialization and economic cycles more generally. Arrighi argues in The Long Twentieth Century that the history of capitalism has been defined by “cycles of accumulation,” in which a succession of hegemonic centers of global economic activity rise and fall as they pass from periods of material expansion, when these centers invest chiefly in production and trade networks, to periods of financial expansion, when they turn increasingly to banking, credit, and speculation. The end of each cycle foretells a shift in political hegemony from one world city, region, or empire to another. Genoa gives way to Amsterdam, which gives way to London, which gives way to New York. At the beginning of each cycle, what Arrighi calls a “long century,” technological developments, access to newly valuable natural resources, or political innovations propel a new region to productive supremacy. That supremacy eventually underwrites a new cycle of financial supremacy, during which money, going abroad in search of greater profit, leads to the decline of the current hegemon and funds the rise of another.

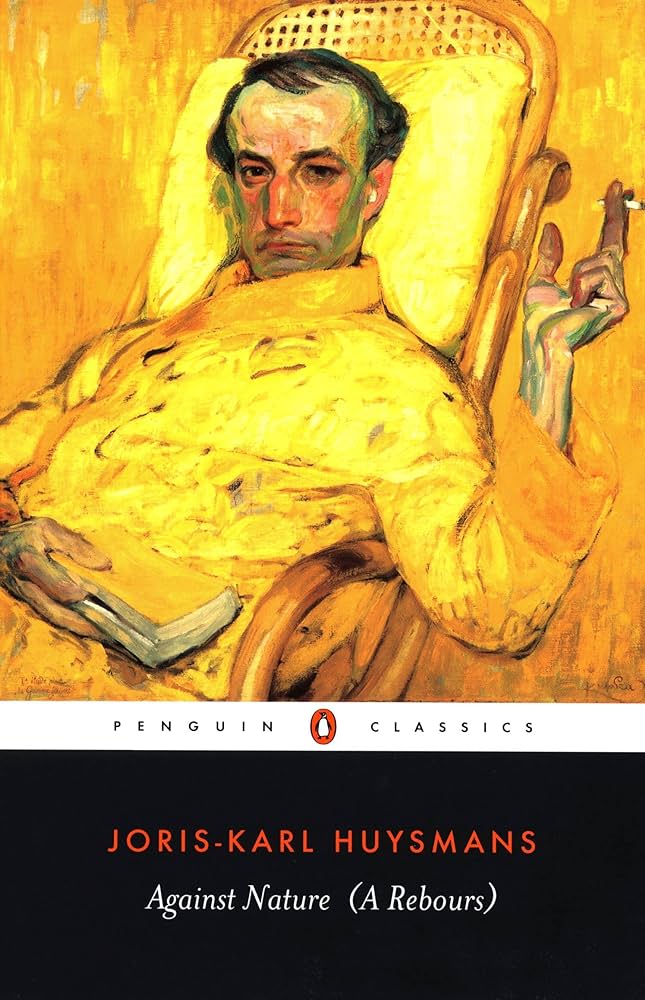

As Arrighi’s history makes clear, and as Gammelgaard perceptively notes, the end of the nineteenth century was a period of financial supremacy, in which dramatic capital accumulation temporarily ensured British and European hegemony over the globe. Arrighi calls such recurrent periods “signal crises,” or, evocatively alluding to the fin de siècle and following Braudel, belles époques. The years after 1870 in Europe were marked by a succession of banking crises, stock-market crashes, and the so-called Long Depression, as well as by rampant speculation in overseas colonies and in large infrastructure projects like railways and canals. Gammelgaard accordingly reads Joris-Karl Huysmans’s classic 1884 decadent novel À rebours as a response to economic reality that, despite its celebration of aesthetic withdrawal, is no less astute in its depiction of the financialized culture than stock-exchange novels from the period, like Anthony Trollope’s The Way We Live Now (1875) and Émile Zola’s L’Argent (1891).[1] Highlighting Huysmans’s descriptions of exotic flowers and the Latin language, Gammelgaard connects the novel with two coeval intellectual developments—Saussure’s structural linguistics and William Stanley Jevons marginal revolution in economics—that also point to a crisis of signification that reflects the abstracting character of finance capital.[2] Yet, while Saussure and Jevons lean into that abstracting character, Huysmans undertakes a kind of rear-guard action by insisting on the sensory and material, as if, Gammelgaard writes, he were “trying to figure out what to do with a materiality that can no longer really be understood through the models we know.”

I find this claim compelling, though to my mind it leaves perhaps the crucial question posed by the essay largely unanswered: what is it about the concept, history, or aesthetics of decadence that allows it to speak so precisely to the conditions of financialization? Many other movements in the period were immersed in sensuality (impressionism) or fascinated with images of cultural disintegration (naturalism), so these characteristics do not obviously set decadence apart. Writers like Trollope and Zola confronted the effects of late-century financialization more directly, and critics like John Ruskin pilloried bourgeois capitalism in much more incisive ways than the decadents did. Indeed, decadent writers rarely concern themselves the financial life of their characters, though matters of wealth, debt, credit, and investment do arise in their works. So, what does decadence offer that other contemporary writers and artists do not?

I want to offer two answers to this question. The first emerges from the literature on financialization itself. Since its earliest conceptualization, the notion of finance capital has been closely and persistently associated with the sense of lateness and decline. In the third volume of Capital, Marx casts finance as “the most superficial and fetishized form” of capital—a putative endpoint, in which normatively social (if alienated) relations are pushed to distorted lengths (1981, 515). Later theorists of finance capital like Rudolf Hilferding and Vladimir Lenin explicitly use the language of decadence to describe the phenomenon. In Imperialism: The Last Stage of Capitalism, Lenin describes finance as capitalism that has “grown ripe, over-ripe and rotten” (1917, 128). The word “last” (высшая) in his title is bitingly ironic in Russian, suggesting not just the end of a temporal sequence but also the characteristically decadent qualities of excess, exorbitance, and overrefinement. Arrighi, as we have seen, associates financialization with the decline of hegemonic regions, and draws his name for periods of signal crisis from the fin de siècle. In a passage that Arrighi cites as the inspiration for his project, Braudel calls belles époques “a sign of autumn,” an image that draws from the store of decadent tropes (1984, 246).

Decadence, then, is not only an aesthetic of financialization, as Gammelgaard shows, but is also part of the received conceptual framework for describing finance capital, which emerges as a manifestly decadent object. Both before and after the fin de siècle, commentators have drawn upon the concept to explain the rapid changes in the class system and generalized sense of historical transition that characterizes signal crises. The most important modern theorist of cultural decadence, the Baron de Montesquieu, wrote his influential Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline (1734) in the wake of the so-called Financial Revolution in England, which created the Bank of England and authorized the sale of government bonds, and little more than a decade after the ruinous South Sea Bubble of 1721. In 1796, Thomas Paine published a pamphlet entitled The Decline and Fall of the English System of Finance that took aim at excessive government borrowing. Braudel’s studies of capitalist economic cycles were written during the signal crisis of the 1970s, when contemporary regimes of finance began to emerge. The pattern also holds true for our contemporary era of financialization, as in works like The Hunger Games series (2008-10), where the capitol of Panem evokes decadent Rome in both its name (panem et circenses) and in the stereotypically decadent ways of its residents. The titular protagonist of Glen Duncan’s The Last Werewolf (2011) is modeled in large part on decadent characters like Des Esseintes.

We can draw two salient points from the persistent copresence of decadence and finance. Decadence, to begin with, provides a durable rhetoric and set of historical examples (above all, imperial Rome) for describing the excesses inherent to moments of financialization. As Montesquieu writes in his Cahiers: “in empires, nothing comes closer to decadence than great prosperity” (1951, 82). More significantly, though, it is historical concepts like decadence that allow critics to see signal crises as characteristic and recurring features of history, and not just as random accidents, signs of divine judgment, or evidence of human perversity. Tracing its lineage to cyclical theories of political history from antiquity and early modernity (Polybius, Machiavelli, Vico), the notion of decadence encourages commentators to assimilate present crises to past ones.[3] So, while financialization helps us historicize decadence, decadence also helps us historicize theories of financialization. In particular, it helps us recognize the ways in which such theories persistently frame rapid capital accumulation in terms of a familiar narrative of rise and decline. Decadence here is a cognitive map—shared by commentators on the left and the right—which interprets financialization in moral, affective, and historical terms. Finance capital is at once natural and perverse, the epitome and the exception, its demise both inevitable and richly deserved.

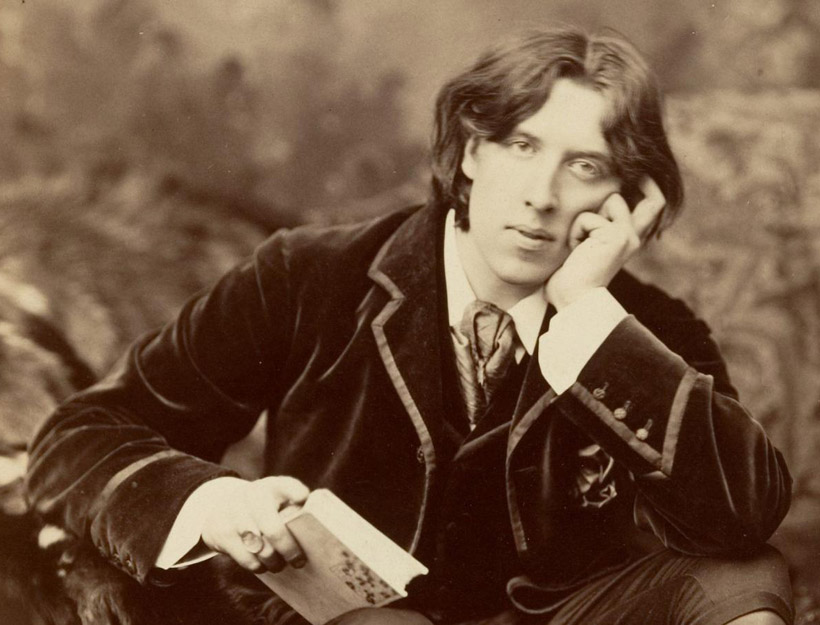

The second answer to the question of why decadence would emerge as a key finance aesthetic during the belle époque of the nineteenth century can be found in the aesthetics of decadence itself. Although scholars have tended to associate financialization with postmodernism, decadence offers an even more apposite model. Gammelgaard directs us to the decadent fascination with the sensual, material, and hedonistic, which she sees as a response to the loss of meaning under the regime of finance. But there are many other ways in which decadence might be seen to thematize the logic of financialization. Consider the centrality of fiction, artifice, and the lie in decadent aesthetics. In his 1890 dialogue “The Decay of Lying,” Oscar Wilde argues that reality is the “solvent that breaks up Art, the enemy that lays waste to her house” (2007, 83). “Art finds her own perfection within,” he writes, “and not outside of, herself. She is not to be judged by any external standard of resemblance” (2007, 89). It is not difficult see a parallel between Wilde’s celebration of artifice and the characterization of finance as “fictitious” or “imaginary,” an entity opposed to what has long been termed the “real economy.” Finance, according to this pervasive opposition, is the unnatural product of art and human ingenuity, not of genuine human labor. Rather than lamenting such an apparent loss of materiality, decadent writers like Wilde parodically lean into it. They criticize novelistic realism for its retrograde commitment to fact and celebrate figures like the dandy, who treats life as a work of art. As Huysmans writes: “artifice was considered by Des Esseintes to be the distinctive mark of human genius. Nature, he used to say, has had her day” (2003, 22). He compares landscapes and sunsets to unimaginative tradesmen and shopkeepers—dealers in the wares of the “real economy.” The very difference between the “real” and the “artificial” that is foundational to traditional definitions of finance capital becomes an object of contemplation. By perversely celebrating art over nature, writers like Wilde and Huysmans thus anticipate Laura Finch’s observation that “The fictionality of finance is, of course, a fiction itself” (2015, 732).

The decadent interest in collecting and collections, which scholars have long tied to nineteenth-century consumerism, might also be understood as a reflection on financial accumulation. The sheer materiality of a collection offers more support to Gammelgaard’s claim that decadence challenges the abstractions of finance capital. But collections evoke the logic of financialization on a different level as well. Joshua Clover has suggested that financialization engenders an “autumnal” aesthetic, which transmutes categories of time into space, dissimulating the labor-time that lies at the origin of value.[4] There is no better image of this transmutation than a decadent collection, which brings objects created at different historical moments and by different cultures into a single physical space. In his 1889 essay “Pen, Pencil, and Poison,” for example, Wilde draws attention to collections of his subject, Thomas Griffiths Wainewright, for whom “All beautiful things belong to the same age”: “we find the delicate fictile vase of the Greek … and behind it hangs an engraving of the ‘Delphic Sibyl’ of Michelangelo … Here is a bit of Florentine majolica, and here a rude lamp from some Roman tomb” (2007, 108-9). There are books by French poets, antique gems, and works by Turner. These objects are at once material things and evidence of the eclectic tastes of the decadent collector, whose curatorial eye subsumes temporal differences under the evaluative categories of the beautiful, the exceptional, or (like Des Esseintes’s plants) the perverse. It is such conceptual values—and not the monetary value of the objects—that justify their inclusion in the collection. In other words, the value of the collected objects, like that of many financial instruments, is more imaginary than “real.”

Perhaps the most suggestive connection between decadence and financialization, however, lies in a key nineteenth-century analytical category that Gammelgaard’s attention to linguistic signification unfortunately obscures: decadent style. The major concept under which decadent texts were categorized by contemporary critics, decadent style was (at first) a denigrating name for literary forms that transgressed against classical harmony and simplicity. Bloated, unbalanced, and marked by a superabundance of description and erudition, this style, for critics, mirrored the pathologies of its age. In the single most important characterization of decadence, Paul Bourget describes Charles Baudelaire’s decadent style, in proto-Durkheimian terms, as an index of social of disintegration: the book gives way to the page, the page to the sentence, and the sentence to the word. Friedrich Nietzsche would famously borrow this definition to define Richard Wagner’s decadent style, and along with it the atomizing nature of democratic politics.

The concept of decadent style was first proposed by the French critic Désiré Nisard in his 1834 study of first-century Latin poetry, Études de moeurs et de critique sur les poètes Latins de la décadence. When Bourget wrote his essay on Baudelaire, he was appropriating a term that was already well-established in French critical discourse. Writing at a moment that Marx, in The Class Struggles in France (1850), associates with the rise of the “finance aristocracy,” Nisard casts the style of poets like Lucan as a figure both for the decline of the Roman Empire and for the economic conditions of his own age. Marx sees the finance aristocracy as a bourgeois equivalent of the Lumpenproletariat—a group made up of former outsiders (primarily Jews, he notes), who improbably ascended to the height of cultural power after the 1830 July Revolution. Nisard sees something similar in ancient Rome. Arriving in the imperial metropole from colonial outposts in Iberia and North Africa, decadent Latin poets like Lucan and Martial subjected hallowed Roman literary traditions to their (bad) provincial taste, casting it in what Nisard terms “the bizarre jargon of the marketplace” (1834, I, 129). Nisard concludes his study with a comparison between decadent Roman poets and “decadent” contemporaries like Victor Hugo, whose poetic innovations he accuses of the same excessive reliance on description and empty erudition as his ancient forbears.

Read together, Nisard and Marx bring out something about financialized moments that does not often receive its due in critical finance studies: their disruption of the existing class structure. Finance elevates certain outsiders to new positions of privilege, for which they quickly come under attack by rival classes, who decry their “decadent” ways. Decadence in this case is the name given to formerly marginal members of society who have begun making their mark on a conceptual order that treats certain traditions, whether literary or economic, as unquestionably natural. While Nisard saw decadent style as something to be lamented, later decadent writers like Huysmans and Wilde, working in yet another moment of financialization, saw it as a cause for celebration. Des Esseintes’s Latin library, described in chapter three of À rebours, explicitly repudiates the scions of the Golden Age (Cicero, Horace, Virgil) in favor of precisely those “lumpen” outsiders like Lucan that Nisard and other critics of late-Latin style rejected. The sexologist and social reformer Havelock Ellis crystalized just this attitude when he compared Huysmans’s decadent style with the “fantastic mingling of youth and age, of decayed Latinity, of tumultuous youthful Christianity” that characterized African writers like Tertullian and Augustine (1898, 158). For Ellis, early Christianity embodies a condition of uneven and combined cultural development that anticipates the fin-de-siècle belle époque.[5]

Like many other fin-de-siècle decadent writers—most of them queers, provincials, colonial subjects, and foreigners—Huysmans turns Nisard’s diagnostic category inside out, rendering what is typically a conservative cultural diagnosis potentially radical. The striking disruptions to the class structures that shape the culture of a belle époque may elicit apocalyptic prognostications from traditionalists (of all political stripes), but they also open up new possibilities for the formerly marginalized. This was certainly true of the fin de siècle, which saw the emergence of modern queer identity and the beginnings of anticolonial movements. Despite its common association with philosophical pessimism, the decadent aesthetic speaks to just this sense of new possibility. Condemnations of finance as the “last” or a “late” version of capitalism, which adopt the language of decadence only as a theory of bitter ends, crucially miss its longstanding association with new beginnings. As Neville Morely has put it, decadence “marks the moment when the future begins to come within reach, the point where the present weakens enough to make an alternative conceivable” (2004, 574).

In “Culture and Finance Capital,” his influential review of The Long Twentieth Century, Fredric Jameson, providing yet another example of the decadent logic of finance, maps Arrighi’s theory of economic cycles onto the familiar stylistic trinity of realism, modernism, and postmodernism. Each step in the stylistic sequence, Jameson argues, is marked by increasing abstraction, reflecting the growing dominance of finance capital. While realism retains a residual commitment to the concrete, modernism frees form and color from their dependence on objects, and postmodernism, as the terminal point in this evolution, detaches artistic styles entirely from their connection to history. Jameson gave no attention to decadent style in his essay, but he should have.[6] More, perhaps, than any modern literary and artistic style, decadence is attuned to historical repetition, and since its earliest adumbration in the 1830s has been understood as the recurrent mark of so-called “decadent” ages—beginning, of course, with the paradigmatic case of imperial Rome. Jameson’s progressive narrative of stylistic change overlooks the cyclical nature of financialization in ways that closer attention to decadent writing would have precluded. The long twentieth century, as I noted above, raised financial markets to unprecedented prominence, but this is only an intensification of economic circumstances that have analogies in other long centuries, something both Arrighi and Braudel insist upon in their longue durée histories of capitalism. Indeed, as theorists from Paine to Lenin to Arrighi himself seem to recognize, if only at the level of imagery, decadence is the house style of financialization. Hence my concluding point: Not only should scholars of decadence follow Gammelgaard’s lead and attend closely to the literature on financialization, but scholars interested in financialization would learn much by attending more closely to the literature on and of decadence.

Matthew Potolsky is Professor of English at the University of Utah, where he teaches nineteenth-century literature and literary theory. He is the author of three scholarly monographs: Mimesis (2006), The Decadent Republic of Letters: Taste, Politics, and Cosmopolitan Community from Baudelaire to Beardsley (2013), and The National Security Sublime: On the Aesthetics of Government Secrecy (2019). He is also the editor of Classical Studies (2021), the eighth volume of Oxford University Press’ The Collected Works of Walter Pater; and co-editor of Perennial Decay: On the Aesthetics and Politics of Decadence (1999).

References

Arrighi, Giovanni. 2010. The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power and the Origins of Our Times. London: Verso.

Braudel, Fernand. 1984. Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century, III: The Perspective of the World, translated by Siân Reynolds. New York: Harper and Row.

Clover, Joshua. 2011. “Autumn of the System: Poetry and Finance Capital.” Journal of Narrative Theory 41, no. 1: 34-52.

Dowling, Linda. 1983. Language and Decadence in the Victorian Fin de Siècle. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ellis, Havelock. 1898. Affirmations. London: Walter Scott.

Esty, Jed. 2016. “Realism Wars.” Novel: A Forum on Fiction 49, no. 2: 316-42.

Finch, Laura. 2015. “The Un-real Deal: Financial Fiction, Fictional Finance, and the Financial Crisis.” Journal of American Studies 49, no. 4: 731-53.

Gagnier, Regenia. 2000. The Insatiability of Human Wants: Economics and Aesthetics in Market Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gaillard, Françoise. 1980. “A rebours ou l’inversion des signes.” In L’Esprit de la décadence I. Nantes: Minard.

Gasché, Rodolphe. 1988. “The Falls of History: Huysmans’s A rebours.” Yale French Studies 74: 183–204.

Huysmans, Joris-Karl. 2003. Against Nature (À Rebours), translated by Robert Baldick. London: Penguin.

Jameson, Fredric. 1997. “Culture and Finance Capital.” Critical Inquiry 24, no. 1: 246-65.

Lenin, Vladimir. 1917. Imperialism: The Last Stage of Capitalism. London: Communist Party of Great Britain.

Marx, Karl. 1960. The Class Struggles in France, 1848-1850. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Marx, Karl. 1981. Capital, Vol. 3, translated by David Fernbach. London: Penguin.

Montesquieu, Charles de Secondat. 1951. Cahiers (1716-1755), edited by Bernard Grasset. Paris: Grasset.

Morely, Neville. 2004. “Decadence as a Theory of History.” New Literary History 35, no. 4: 573-85.

Nisard, Désiré. 1834. Études de moeurs et de critique sur les poètes Latins de la décadence. 3 vols. Brussels: Louis Hauman.

Sewell, William H. 2012. “Economic Crises and the Shape of Modern History.” Public Culture 24, no. 2: 303-27.

Spackman, Barbara. 1999. “Interversions.” In Perennial Decay: On the Aesthetics and Politics of Decadence, edited by Liz Constable, Dennis Denisoff, and Matthew Potolsky, pp. 35-49. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Wilde, Oscar. 2007. The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, IV: Criticism, edited by Josephine M. Guy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[1] Extending her claim, we might also place À rebours in the company of more recent finance-era classics like Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities (1987) and Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (1991), both of which recall fin-de-siècle forbears.

[2] Gammelgaard treads overfamiliar terrain here. The comparison of Jevons and Saussure recapitulates the insights of the New Economic Criticism; Gagnier (2000) explores the connection between fin-de-siècle writing and the marginal revolution; Dowling (1983) finds a key to decadent aesthetics in the history of linguistics. Other scholars—notably Gaillard (1980), Gasché (1988), and Spackman (1999)—explore the unusual workings of language and signification in Huysmans’s novel.

[3] On the extent to which economic crises function as historical events, see Sewell.

[4] Clover associates the term with W.B. Yeats, a writer deeply influenced by 1890s poetry, but finds his chief examples of autumnal style in postmodern figures like Pynchon and Ashbury.

[5] In his 1895 introduction to The Class Struggles in France, Friedrich Engels compares contemporary socialists to early Christians: “The Emperor Diocletian could no longer quietly look on while order, obedience and discipline in his army were being undermined…He promulgated an anti-Socialist—beg pardon, I meant to say anti-Christian—law” (1960, 41). The origin for this analogy is probably Ernest Renan, but it was clearly popular at the fin de siècle. It is worth asking, in this regard, whether Leon Trotsky’s theory of uneven and combined development might not also have a decadent lineage. Trotsky’s literary criticism from the 1920s demonstrates an extensive knowledge (mostly critical) of fin-de-siècle literary forms, and his familiarity with such works might well have inflected his discussion of the peculiarities of Russian development in The History of the Russian Revolution (1930). He offers there a strikingly “decadent” theory of economic development.

[6] Jameson does make a surprising reference to Wilde in “Culture and Finance Capital.” Noting that Marxist critics have tended to avoid the exploring the stylistic implications of modes of production because it requires too many mediations, he writes that this avoidance is “no doubt in the spirit in which Oscar Wilde complained that socialism required too many evenings” (1997, 253). Gammelgaard’s account of decadence, it is worth noting, would, in Jameson’s sequence, be most akin to realism. For an effort to think cyclically about the resonances of fin-de-siècle forms, specifically about their opposition to realism, see Esty (2016).