Tunisia is gripped by the most serious political crisis since 2011, a crisis in trust between the government and its opponents compounded by rise in violent terrorism and a collapsing economy. Yet, one local trade union may save the day. If it did, it would not be doing so for the first time. For this is no ordinary union. The Tunisian General Union of Labour (UGTT) has affected the character of Tunisia as a whole since the late 1940s. It impacted significantly the 2011 revolution and the transition period, and is likely to impact the future. In this, it is unparalleled elsewhere in the Arab world. And it is largely because of it that one may confidently say that Tunisia is not Egypt, or Syria or Yemen. Indeed, to understand Tunisia, one must get to grips with its labour movement.

Trade unions and the construction of a specifically Tunisian configuration of protest

by Mohamed-Salah Omri

St John’s College, University of Oxford

Incubator of protest and refuge

Trade unionism in Tunisia goes back to the early twentieth century and has had both local and international features since its inception by Mohamed Ali al Hammi (1890-1928), founder of the General Federation of Tunisian Workers in 1924. But it was with the charismatic and visionary Farhat Hached (1914-1952) that a home grown strong organization would emerge. Hached learned union activism and organizing within the French CGT for 15 years before splitting from it to start UGTT in 1946. His union quickly gained support, clout and international ties, which it used to pressure the French for more social and political rights for Tunisia and to consolidate the union’s position as a key component of the national liberation movement. Because of that birth in the midst of the struggle against French colonialism, the union had political involvement from the start, a line it has maintained and guarded vigorously since.

UGTT has enjoyed continuity in history and presence across the country, which parallel only the ruling party at its height under Bourguiba and Ben Ali. With 150 offices across the country, an office in every governorate and district, and over 680 000 current members, it constituted a credible alternative to this party’s power and a locus of resistance to it, so much so that to be a unionist became a euphemism for being an opponent or an activist against the ruling party. UGTT has been the outcome of Tunisian resistance and its incubator at the same time. For example, in 1984 it aligned itself with the rioting people during the bread revolt; in 2008, it was the main catalyst of the disobedience movement in the Mining Basin of Gafsa; and, come December 2010, UGTT, particularly its teachers’ unions and local offices, became the headquarters of revolt against Ben Ali. The fit between the revolution and UGTT was almost natural since the main demands of the rising masses, namely jobs, national dignity and freedom have been on the agenda of the union all along. The union was also very well represented in the remote hinterland where the revolution started.

For these reasons, successive governments tried to compromise with, co-opt, repress or change the union, depending on the situation and the balance of power at hand.

In 1978, UGTT went on general strike to protest what amounted to a coup perpetrated by the Bourguiba government to change a union leadership judged to be too oppositional and too powerful. The cost was the worst setback in the union’s history since the assassination of its founder in 1952. The entire leadership of the union was put on trial and replaced by regime loyalists. Ensuing popular riots were repressed by the army, resulting in tens of deaths. In 2012, UGTT sensed a repeat of 1978 and an attempt against its very existence. On December the 4th, 2012 as the union was gearing up to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the assassination of its founder, its iconic headquarters, Place Mohamed Ali, were attacked by groups known as Leagues for the Protection of the Revolution. The incident was ugly, public and of immediate impact. These leagues, which originated in community organisation in cities across the country designed to keep order and security immediately after January 14, but were later disbanded, and become dominated by Islamists of various orientations. On August 26, 2013, a group of trade unionists founded the Tunisian Labour Organization, which aims according to its leaders at correcting the direction of UGTT. To the first attack, UGTT responded by boycotting the government, organizing regional strikes and marches, and eventually calling for a general strike on Thursday the 13th of December, the first such action since 1978. To the founding of a parallel union, Sami Tahri, the UGTT spokesman responded, not only dismissively but with some arrogance, that this is no more than the reaction of losers who could not win elected offices in UGTT and failed to drag the union into the “house of obedience”, referring to the new organization’s ties to Al Nahdah party. Tahri’s confident tone and political statement are backed up by history, which demonstrates that UGTT has warded off not one but several attempts of takeover, division or weakening over the past sixty years or so.

Qualified powerbroker

Despite antagonistic relations with governments before and after the revolution, UGTT remains perhaps the only body in the country qualified to resolve disputes peacefully but also offers mediation with a view to present its own positions. After January 2011, it emerged as the key mediator and power broker at the initial phase of the revolution, when all political players trusted and needed it. And it was within the union that the committee which regulated the transition to the elections of 23 October 20111 was formed. At the same time, UGTT used its leverage to secure historic victories for its members and for workers in general, including permanent contracts for over 350,000 temporary workers and pay rises for several sectors, including teachers.

As Tunisia moved from the period of revolutionary harmony in which UGTT played host and facilitator to a political, and even ideological phase, characterised by multiplicity of parties and polarisation of public opinion, UGTT was challenged to keep its engagement in politics without falling under the control of a particular party or indeed turning into one. But, due to historical reasons, which saw leftists channel their energy into trade unionism when their political activities were curtailed, UGTT remained on the left side of politics and, in the face of rising Islamist power, became a place where the left, despite its many newly-formed parties, kept its ties and even strengthened them. For these reasons, UGTT remained strong and decidedly outside the control of Islamists. But they, in turn, could not ignore its role its status, nor could other parties.

It is remarkable, but not surprising, that the current balance of power and much of the rational management of the deep political crisis is run by UGTT and its partners, the Tunisian Association of Human Rights, the Lawyers’ Association and the UTICA (the Tunisian Union of Industry and Commerce). Today all parties speak through UGTT and on the basis of its initiative, which consists in dissolving the current government, the appointment of a non-political government, curtailing the work of the ANC (National Constituent Assembly), reviewing top government appointments and dissolving the UGTT’s arch enemy, the Leagues for the Defence of the Revolution. Union leaders are known to be experienced negotiators and patient and tireless activists. They honed their skills over decades of settling disputes and negotiating deals. For this reasons, they have been able to conduct marathon negotiations with the opposing parties and remain above accusations of outright bias.

The construction of a specifically Tunisian configuration of protest

With a labour movement engrained in the political culture of the country, and at all levels, a culture of trade unionism has become a component of Tunisian society. There has not been a proper sociology of this. But the implications are important. I enumerate some of them here in the form of observations.

• Protest culture in Tunisia has been deeply affected by labour unionism. It has been tenacious, issue-oriented, uneven and limited in terms of popular reach. The unevenness runs along the degree of unionisation and militancy. For example, the education sector tended to be the most vocal and better organised. The rural areas as well as a large portion of the middle class have been left out of this movement because it had no or less union affiliation. Even intellectuals had to work within the confines or in synch with unions.

• One challenge to the Leftist parties after 2011 has been how to move away from being trade unionist and become politicians, in other words, how to think beyond small issues and using unionist means in order to tackle wider issues and adopt their attendant methods. This has been expressed by prominent Leftists, such as the late Chokri Belaid, who challenged his heavily unitized party to think like a party, not like a union. This meant finding different, broader bases for political alliances and laying out projects for the society at large.

• Post 2011 alliances, particularly the current ones, have largely kept the patterns of alliance within UGTT. The Popular Front and its closest allies have been collaborating within UGTT for years. Their interlocutors in Nida’ Tunis are also trade unionists, most prominently Tayeb Baccouche, a former Secretary General of UGTT from 1981 to 1984. Furthermore, the Popular Front parties have been unable to recruit members from outside the union bases. Nida Tunis and Al Nahdha are different in this respect. Nida’ caters to a base along socioeconomic means and tends to attract the middle class and even wealthy, liberal members. Al Nahdha caters to religious or political affiliation which cross the class divide.

• There have been close relations between student unionism (UGET) and the wider labour movement both in activism and in membership, as the university tended to be a training ground, which prepared leaders to be active in UGTT once they leave education. UGET, founded in 1952 worked closely with UGTT since then; and both would gradually move away from the ruling party, albeit at different pace. The radicalisation of UGTT in fact finds its roots in this flow as the university in Tunisia, particularly in the 1970s and 80s was a space of radical activism and left wing politics.

• A key paradox of UGTT has been its support of women causes but scarcely promoting women to its leadership. The widespread practice of limiting women’s access to the glass ceiling does not truly apply to other aspects of Tunisian civil society institutions. The President of business association is a woman, so are the leaders of the Journalists Association and the Council of Judges. While the absence of women in leadership could be explained by the very nature of trade union work, which requires time and presence in public places which are not very friendly to women a such as cafes, but this remains a serious lacuna of UGTT, UGTT is challenged to be in line in this area. In Tunisia, this is particularly important as the role of women has been a marking feature of the society at large and of its protest culture in particular, throughout the post independent period, within and outside the labor movement.

• The union has also been accused of bureaucracy and corruption at the top level, which triggered several attempts at internal reform and even rebellion over the years. There is in fact a lot of power and money associated with being a top union official in Tunisia, which, in a climate of rampant corruption has led many leaders to cozy up with businesses and government officials, the discredited former Secretary General Sahbbani is an example of this. But this did not affect grass root support and local chapters of the union who did not enjoy the benefits of high union office. Post 2011, UGTT seems to have regained a cohesion it lacked during the ben Ali period when the gap between the leadership and the grassroots were wide.

• The practice of democracy and plurality in Tunisia over the past half century was almost the exclusive domain of the university and the trade unions. Both had electoral campaigns for office, sometimes outside the control of the state, as was the case in the university during the 1970s and 80s. In fact, the state stepped in specifically to quell such practice when the outcome was not in its favour. Two memorable incidents testify to this. The first one was in 1972 when the majority of students defeated the ruling party lists and secured the independence of UGET. The second was is in 1978 when the ruling party was overruled by UGTT leadership. In both cases, the government proceeded to take over or ban the unions. The type of democratic practice in these two institutions was also in place in the lawyers association and some other minor civil society associations which were all severely repressed, notably, the Judges Association, the Tunisian League of Human Rights and the Journalist Association. It is no surprise that two of these are now leading the reconciliation effort and that all four are working in concert and at the forefront of preserving the aims of the revolution, particularly freedom, dignity and the right to work. The coming together of these associations has, I argue, mutually affected all of them, not only in terms of widening the field of protest, but also in terms of brining to the fore the wider issues of human rights and freedoms, which were not at the forefront of UGTT’s preoccupations, notably at the level of the leadership. .Democratic practice was therefore linked not to normal running of society, i.e., as a practice of citizenship, but as an opposition or resistance activity. This gave democracy a militant edge, which it did not lose but also affected its character.

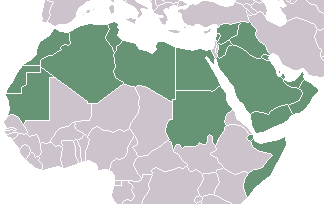

• A combination of symbolic capital of resistance accumulated over decades, a record of results for its members and a well-oiled machine at the level of organisation across the country and every sector of the economy, made UGTT unassailable and unavoidable at the same time. UGTT has been key feature of Tunisian political and social life and a defining element of what may be called the Tunisian exception in the MENA region. For this reason, in times of national discord, UGTT is still capable of credible mediation or power breaking. It also remains a key guarantor that social justice, a main aim of the revolution, can remain on the agenda. Its own challenges are to remain the strongest union at a time when three other split unions are in place and to maintain a political role now that politics has been largely turned over to political parties.

• This gradual coming together of these strong civil society institutions has given shape to a critical mass whose weight is impossible to ignore. I would even argue that whoever manages to dominate this coalition is likely to shape the future of the country and its revolution. Al Nahdha ignores this coalition at its own peril. If Al Nahdha does not accept the solution the UGTT and its partners have negotiated, they will be forced to form an open alliance with the opposition in a coalition, which will become hard to beat. Together, they are capable of ushering the fall of Al Nahdha’s government in stage a repeat of the January 14 mass protests and strikes.• The confluence between a largely secular and humanist education and an engrained labour activism have been, I claim, the main bases of a Tunisian formation, which allowed it to develop a culture of resistance to authoritarianism with a specific humanist and social justice content. An alignment of these two elements against Islamists is now taking place, which, unlike matters in Egypt, leaves the army well out of the game and may bring back hope in the success of the transition period.