a review of Frank Pasquale, The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information (Harvard University Press, 2015)

a review of Frank Pasquale, The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information (Harvard University Press, 2015)

by Nicole Dewandre

~

1. Introduction

This review is informed by its author’s specific standpoint: first, a lifelong experience in a policy-making environment, i.e. the European Commission; and, second, a passion for the work of Hannah Arendt and the conviction that she has a great deal to offer to politics and policy-making in this emerging hyperconnected era. As advisor for societal issues at DG Connect, the department of the European Commission in charge of ICT policy at EU level, I have had the privilege of convening the Onlife Initiative, which explored the consequences of the changes brought about by the deployment of ICTs on the public space and on the expectations toward policy-making. This collective thought exercise, which took place in 2012-2013, was strongly inspired by Hannah Arendt’s 1958 book The Human Condition.

This is the background against which I read the The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms Behind Money and Information by Frank Pasquale (references to which are indicated here parenthetically by page number). Two of the meanings of “black box“—a device that keeps track of everything during a flight, on the one hand, and the node of a system that prevents an observer from identifying the link(s) between input and output, on the other hand—serve as apt metaphors for today’s emerging Big Data environment.

Pasquale digs deep into three sectors that are at the root of what he calls the black box society: reputation (how we are rated and ranked), search (how we use ratings and rankings to organize the world), and finance (money and its derivatives, whose flows depend crucially on forms of reputation and search). Algorithms and Big Data have permeated these three activities to a point where disconnection with human judgment or control can transmogrify them into blind zombies, opening new risks, affordances and opportunities. We are far from the ideal representation of algorithms as support for decision-making. In these three areas, decision-making has been taken over by algorithms, and there is no “invisible hand” ensuring that profit-driven corporate strategies will deliver fairness or improve the quality of life.

The EU and the US contexts are both distinct and similar. In this review, I shall not comment on Pasquale’s specific policy recommendations in detail, even if as European, I appreciate the numerous references to European law and policy that Pasquale commends as good practices (ranging from digital competition law, to welfare state provision, to privacy policies). I shall instead comment from a meta-perspective, that of challenging the worldview that implicitly undergirds policy-making on both sides of the Atlantic.

2. A Meta-perspective on The Black Box Society

The meta-perspective as I see it is itself twofold: (i) we are stuck with Modern referential frameworks, which hinder our ability to attend to changing human needs, desires and expectations in this emerging hyperconnected era, and (ii) the personification of corporations in policymaking reveals shortcomings in the current representation of agents as interest-led beings.

a) Game over for Modernity!

As stated by the Onlife Initiative in its “Onlife Manifesto,” through its expression “Game over for Modernity?“, it is time for politics and policy-making to leave Modernity behind. That does not mean going back to the Middle Ages, as feared by some, but instead stepping firmly into this new era that is coming to us. I believe with Genevieve Bell and Paul Dourish that it is more effective to consider that we are now entering into the ubiquitous computing era instead of looking at it as if it was approaching fast.[1] With the miniaturisation of devices and sensors, with mobile access to broadband internet and with the generalized connectivity of objects as well as of people, not only do we witness an increase of the online world, but, more fundamentally, a collapse of the distinction between the online and the offline worlds, and therefore a radically new socio-technico-natural compound. We live in an environment which is increasingly reactive and talkative as a result of the intricate mix between off-line and online universes. Human interactions are also deeply affected by this new socio-technico-natural compound, as they are or will soon be “sticky”, i.e. leave a material trace by default and this for the first time in history. These new affordances and constraints destabilize profoundly our Modern conceptual frameworks, which rely on distinctions that are blurring, such as the one between the real and the virtual or the ones between humans, artefacts and nature, understood with mental categories dating back from the Enlightenment and before. The very expression “post-Modern” is not accurate anymore or is too shy, as it continues to position Modernity as its reference point. It is time to give a proper name to this new era we are stepping into, and hyperconnectivity may be such a name.

Policy-making however continues to rely heavily on Modern conceptual frameworks, and this not only from the policy-makers’ point of view but more widely from all those engaging in the public debate. There are many structuring features of the Modern conceptual frameworks and it goes certainly beyond this review to address them thoroughly. However, when it comes to addressing the challenges described by The Black Box Society, it is important to mention the epistemological stance that has been spelled out brilliantly by Susan H. Williams in her Truth, Autonomy, and Speech: Feminist Theory and the First Amendment: “the connection forged in Cartesianism between knowledge and power”[2]. Before encountering Susan Williams’s work, I came to refer to this stance less elegantly with the expression “omniscience-omnipotence utopia”[3]. Williams writes that “this epistemological stance has come to be so widely accepted and so much a part of many of our social institutions that it is almost invisible to us” and that “as a result, lawyers and judges operate largely unself-consciously with this epistemology”[4]. To Williams’s “lawyers and judges”, we should add policy-makers and stakeholders. This Cartesian epistemological stance grounds the conviction that the world can be elucidated in causal terms, that knowledge is about prediction and control, and that there is no limit to what men can achieve provided they have the will and the knowledge. In this Modern worldview, men are considered as rational subjects and their freedom is synonymous with control and autonomy. The fact that we have a limited lifetime and attention span is out of the picture as is the human’s inherent relationality. Issues are framed as if transparency and control is all that men need to make their own way.

1) One-Way Mirror or Social Hypergravity?

Frank Pasquale is well aware of and has contributed to the emerging critique of transparency and he states clearly that “transparency is not just an end in itself” (8). However, there are traces of the Modern reliance on transparency as regulative ideal in the Black Box Society. One of them is when he mobilizes the one-way mirror metaphor. He writes:

We do not live in a peaceable kingdom of private walled gardens; the contemporary world more closely resembles a one-way mirror. Important corporate actors have unprecedented knowledge of the minutiae of our daily lives, while we know little to nothing about how they use this knowledge to influence the important decisions that we—and they—make. (9)

I refrain from considering the Big Data environment as an environment that “makes sense” on its own, provided someone has access to as much data as possible. In other words, the algorithms crawling the data can hardly be compared to a “super-spy” providing the data controller with an absolute knowledge.

Another shortcoming of the one-way mirror metaphor is that the implicit corrective is a transparent pane of glass, so the watched can watch the watchers. This reliance on transparency is misleading. I prefer another metaphor that fits better, in my view: to characterise the Big Data environment in a hyperconnected conceptual framework. As alluded to earlier, in contradistinction to the previous centuries and even millennia, human interactions will, by default, be “sticky”, i.e. leave a trace. Evanescence of interactions, which used to be the default for millennia, will instead require active measures to be ensured. So, my metaphor for capturing the radicality and the scope of this change is a change of “social atmosphere” or “social gravity”, as it were. For centuries, we have slowly developed social skills, behaviors and regulations, i.e. a whole ecosystem, to strike a balance between accountability and freedom, in a world where “verba volant and scripta manent“[5], i.e. where human interactions took place in an “atmosphere” with a 1g “social gravity”, where they were evanescent by default and where action had to be taken to register them. Now, with all interactions leaving a trace by default, and each of us going around with his, her or its digital shadow, we are drifting fast towards an era where the “social atmosphere” will be of heavier gravity, say “10g”. The challenge is huge and will require a lot of collective learning and adaptation to develop the literacy and regulatory frameworks that will recreate and sustain the balance between accountability and freedom for all agents, human and corporations.

The heaviness of this new data density stands in-between or is orthogonal to the two phantasms of bright emancipatory promises of Big Data, on the one hand, or frightening fears of Big Brother, on the other hand. Because of this social hypergravity, we, individually and collectively, have indeed to be cautious about the use of Big Data, as we have to be cautious when handling dangerous or unknown substances. This heavier atmosphere, as it were, opens to increased possibilities of hurting others, notably through harassment, bullying and false rumors. The advent of Big Data does not, by itself, provide a “license to fool” nor does it free agents from the need to behave and avoid harming others. Exploiting asymmetries and new affordances to fool or to hurt others is no more acceptable behavior as it was before the advent of Big Data. Hence, although from a different metaphorical standpoint, I support Pasquale’s recommendations to pay increased attention to the new ways the current and emergent practices relying on algorithms in reputation, search and finance may be harmful or misleading and deceptive.

2) The Politics of Transparency or the Exhaustive Labor of Watchdogging?

Another “leftover” of the Modern conceptual framework that surfaces in The Black Box Society is the reliance on watchdogging for ensuring proper behavior by corporate agents. Relying on watchdogging for ensuring proper behavior nurtures the idea that it is all right to behave badly, as long as one is not seen doing do. This reinforces the idea that the qualification of an act depends from it being unveiled or not, as if as long as it goes unnoticed, it is all right. This puts the entire burden on the watchers and no burden whatsoever on the doers. It positions a sort of symbolic face-to-face between supposed mindless firms, who are enabled to pursue their careless strategies as long as they are not put under the light and people who are expected to spend all their time, attention and energy raising indignation against wrong behaviors. Far from empowering the watchers, this framing enslaves them to waste time monitoring actors who should be acting in much better ways already. Indeed, if unacceptable behavior is unveiled, it raises outrage, but outrage is far from bringing a solution per se. If, instead, proper behaviors are witnessed, then the watchers are bound to praise the doers. In both cases, watchers are stuck in a passive, reactive and specular posture, while all the glory or the shame is on the side of the doers. I don’t deny the need to have watchers, but I warn against the temptation of relying excessively on the divide between doers and watchers to police behaviors, without engaging collectively in the formulation of what proper and inappropriate behaviors are. And there is no ready-made consensus about this, so that it requires informed exchange of views and hard collective work. As Pasquale explains in an interview where he defends interpretative approaches to social sciences against quantitative ones:

Interpretive social scientists try to explain events as a text to be clarified, debated, argued about. They do not aspire to model our understanding of people on our understanding of atoms or molecules. The human sciences are not natural sciences. Critical moral questions can’t be settled via quantification, however refined “cost benefit analysis” and other political calculi become. Sometimes the best interpretive social science leads not to consensus, but to ever sharper disagreement about the nature of the phenomena it describes and evaluates. That’s a feature, not a bug, of the method: rather than trying to bury normative differences in jargon, it surfaces them.

The excessive reliance on watchdogging enslaves the citizenry to serve as mere “watchdogs” of corporations and government, and prevents any constructive cooperation with corporations and governments. It drains citizens’ energy for pursuing their own goals and making their own positive contributions to the world, notably by engaging in the collective work required to outline, nurture and maintain the shaping of what accounts for appropriate behaviours.

As a matter of fact, watchdogging would be nothing more than an exhausting laboring activity.

b) The Personification of Corporations

One of the red threads unifying The Black Box Society’s treatment of numerous technical subjects is unveiling the oddness of the comparative postures and status of corporations, on the one hand, and people, on the other hand. As nicely put by Pasquale, “corporate secrecy expands as the privacy of human beings contracts” (26), and, in the meantime, the divide between government and business is narrowing (206). Pasquale points also to the fact that at least since 2001, people have been routinely scrutinized by public agencies to deter the threatening ones from hurting others, while the threats caused by corporate wrongdoings in 2008 gave rise to much less attention and effort to hold corporations to account. He also notes that “at present, corporations and government have united to focus on the citizenry. But why not set government (and its contractors) to work on corporate wrongdoings?” (183) It is my view that these oddnesses go along with what I would call a “sensitive inversion”. Corporations, which are functional beings, are granted sensitivity as if they were human beings, in policy-making imaginaries and narratives, while men and women, who are sensitive beings, are approached in policy-making as if they were functional beings, i.e. consumers, job-holders, investors, bearer of fundamental rights, but never personae per se. The granting of sensitivity to corporations goes beyond the legal aspect of their personhood. It entails that corporations are the one whose so-called needs are taken care of by policy makers, and those who are really addressed to, qua persona. Policies are designed with business needs in mind, to foster their competitiveness or their “fitness”. People are only indirect or secondary beneficiaries of these policies.

The inversion of sensitivity might not be a problem per se, if it opened pragmatically to an effective way to design and implement policies which bear indeed positive effects for men and women in the end. But Pasquale provides ample evidence showing that this is not the case, at least in the three sectors he has looked at more closely, and certainly not in finance.

Pasquale’s critique of the hypostatization of corporations and reduction of humans has many theoretical antecedents. Looking at it from the perspective of Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition illuminates the shortcomings and risks associated with considering corporations as agents in the public space and understanding the consequences of granting them sensitivity, or as it were, human rights. Action is the activity that flows from the fact that men and women are plural and interact with each other: “the human condition of action is plurality”.[6] Plurality is itself a ternary concept made of equality, uniqueness and relationality. First, equality as what we grant to each other when entering into a political relationship. Second, uniqueness refers to the fact that what makes each human a human qua human is precisely that who s/he is is unique. If we treat other humans as interchangeable entities or as characterised by their attributes or qualities, i.e., as a what, we do not treat them as human qua human, but as objects. Last and by no means least, the third component of plurality is the relational and dynamic nature of identity. For Arendt, the disclosure of the who “can almost never be achieved as a wilful purpose, as though one possessed and could dispose of this ‘who’ in the same manner he has and can dispose of his qualities”[7]. The who appears unmistakably to others, but remains somewhat hidden from the self. It is this relational and revelatory character of identity that confers to speech and action such a critical role and that articulates action with identity and freedom. Indeed, for entities for which the who is partly out of reach and matters, appearance in front of others, notably with speech and action, is a necessary condition of revealing that identity:

Action and speech are so closely related because the primordial and specifically human act must at the same time contain the answer to the question asked of every newcomer: who are you? In acting and speaking, men show who they are, they appear. Revelatory quality of speech and action comes to the fore where people are with others and neither for, nor against them, that is in sheer togetherness.[8]

So, in this sense, the public space is the arena where whos appear to other whos, personae to other personae.

For Arendt, the essence of politics is freedom and is grounded in action, not in labour and work. The public space is where agents coexist and experience their plurality, i.e. the fact that they are equal, unique and relational. So, it is much more than the usual American pluralist (i.e., early Dahl-ian) conception of a space where agents worry for exclusively for their own needs by bargaining aggressively. In Arendt’s perspective, the public space is where agents, self-aware of their plural characteristic, interact with each other once their basic needs have been taken care of in the private sphere. As highlighted by Seyla Benhabib in The Reluctant Modernism of Hannah Arendt, “we not only owe to Hannah Arendt’s political philosophy the recovery of the public as a central category for all democratic-liberal politics; we are also indebted to her for the insight that the public and the private are interdependent”.[9] One could not appear in public if s/he or it did not have also a private place, notably to attend to his, her or its basic needs for existence. In Arendtian terms, interactions in the public space take place between agents who are beyond their satiety threshold. Acknowledging satiety is a precondition for engaging with others in a way that is not driven by one’s own interest, but rather by their desire to act together with others—”in sheer togetherness”—and be acknowledged as who they are. If an agent perceives him-, her- or itself and behave only as a profit-maximiser or as an interest-led being, i.e. if s/he or it has no sense of satiety and no self-awareness of the relational and revelatory character of his, her or its identity, then s/he or it cannot be a “who” or an agent in political terms, and therefore, respond of him-, her- or itself. It does simply not deserve -and therefore should not be granted- the status of a persona in the public space.

It is easy to imagine that there can indeed be no freedom below satiety, and that “sheer togetherness” would just be impossible among agents below their satiety level or deprived from having one. This is however the situation we are in, symbolically, when we grant corporations the status of persona while considering efficient and appropriate that they care only for profit-maximisation. For a business, making profit is a condition to stay alive, as for humans, eating is a condition to stay alive. However, in the name of the need to compete on global markets, to foster growth and to provide jobs, policy-makers embrace and legitimize an approach to businesses as profit-maximisers, despite the fact this is a reductionist caricature of what is allowed by the legal framework on company law[10]. So, the condition for businesses to deserve the status of persona in the public space is, no less than for men and women, to attend their whoness and honour their identity, by staying away from behaving according to their narrowly defined interests. It means also to care for the world as much, if not more, as for themselves.

This resonates meaningfully with the quotation from Heraclitus that serves as the epigraph for The Black Box Society: “There is one world in common for those who are awake, but when men are asleep each turns away into a world of his own”. Reading Arendt with Heraclitus’s categories of sleep and wakefulness, one might consider that totalitarianism arises—or is not far away—when human beings are awake in private, but asleep in public, in the sense that they silence their humanness or that their humanness is silenced by others when appearing in public. In this perspective, the merging of markets and politics—as highlighted by Pasquale—could be seen as a generalized sleep in the public space of human beings and corporations, qua personae, while all awakened activities are taking place in the private, exclusively driven by their needs and interests.

In other words—some might find a book like The Black Box Society, which offers a bold reform agenda for numerous agencies, to be too idealistic. But in my view, it falls short of being idealistic enough: there is a missing normative core to the proposals in the book, which can be corrected by democratic, political, and particularly Arendtian theory. If a populace has no acceptance of a certain level of goods and services prevailing as satiating its needs, and if it distorts the revelatory character of identity into an endless pursuit of a limitless growth, it cannot have the proper lens and approach to formulate what it takes to enable the fairness and fair play described in The Black Box Society.

3. Stepping into Hyperconnectivity

1) Agents as Relational Selves

A central feature of the Modern conceptual framework underlying policymaking is the figure of the rational subject as political proxy of humanness. I claim that this is not effective anymore in ensuring a fair and flourishing life for men and women in this emerging hyperconnected era and that we should adopt instead the figure of a “relational self” as it emerges from the Arendtian concept of plurality.

The concept of the rational subject was forged to erect Man over nature. Nowadays, the problem is not so much to distinguish men from nature, but rather to distinguish men—and women—from artefacts. Robots come close to humans and even outperform them, if we continue to define humans as rational subjects. The figure of the rational subject is torn apart between “truncated gods”—when Reason is considered as what brings eventually an overall lucidity—on the one hand, and “smart artefacts”—when reason is nothing more than logical steps or algorithms—on the other hand. Men and women are neither “Deep Blue” nor mere automatons. In between these two phantasms, the humanness of men and women is smashed. This is indeed what happens in the Kafkaesque and ridiculous situations where a thoughtless and mindless approach to Big Data is implemented, and this from both stance, as workers and as consumers. As far as the working environment is concerned, “call centers are the ultimate embodiment of the panoptic workspace. There, workers are monitored all the time” (35). Indeed, this type of overtly monitored working environment is nothing else that a materialisation of the panopticon. As consumers, we all see what Pasquale means when he writes that “far more [of us] don’t even try to engage, given the demoralizing experience of interacting with cyborgish amalgams of drop- down menus, phone trees, and call center staff”. In fact, this mindless use of automation is only the last version of the way we have been thinking for the last decades, i.e. that progress means rationalisation and de-humanisation across the board. The real culprit is not algorithms themselves, but the careless and automaton-like human implementers and managers who act along a conceptual framework according to which rationalisation and control is all that matters. More than the technologies, it is the belief that management is about control and monitoring that makes these environments properly in-human. So, staying stuck with the rational subject as a proxy for humanness, either ends up in smashing our humanness as workers and consumers and, at best, leads to absurd situations where to be free would mean spending all our time controlling we are not controlled.

As a result, keeping the rational subject as the central representation of humanness will increasingly be misleading politically speaking. It fails to provide a compass for treating each other fairly and making appropriate decisions and judgments, in order to impacting positively and meaningfully on human lives.

With her concept of plurality, Arendt offers an alternative to the rational subject for defining humanness: that of the relational self. The relational self, as it emerges from the Arendtian’s concept of plurality[11], is the man, woman or agent self-aware of his, her or its plurality, i.e. the facts that (i) he, she or it is equal to his, her or its fellows; (ii) she, he or it is unique as all other fellows are unique; and (iii) his, her or its identity as a revelatory character requiring to appear among others in order to reveal itself through speech and action. This figure of the relational self accounts for what is essential to protect politically in our humanness in a hyperconnected era, i.e. that we are truly interdependent from the mutual recognition that we grant to each other and that our humanity is precisely grounded in that mutual recognition, much more than in any “objective” difference or criteria that would allow an expert system to sort out human from non-human entities.

The relational self, as arising from Arendt’s plurality, combines relationality and freedom. It resonates deeply with the vision proposed by Susan H. Williams, i.e. the relational model of truth and the narrative model to autonomy, in order to overcome the shortcomings of the Cartesian and liberal approaches to truth and autonomy without throwing the baby, i.e. the notion of agency and responsibility, out with the bathwater, as the social constructionist and feminist critique of the conceptions of truth and autonomy may be understood of doing.[12]

Adopting the relational self as the canonical figure of humanness instead of the rational subject‘s one puts under the light the direct relationship between the quality of interactions, on the one hand, and the quality of life, on the other hand. In contradistinction with transparency and control, which are meant to empower non-relational individuals, relational selves are self-aware that they are in need of respect and fair treatment from others, instead. It also makes room for vulnerability, notably the vulnerability of our attentional spheres, and saturation, i.e. the fact that we have a limited attention span, and are far from making a “free choice” when clicking on “I have read and accept the Terms & Conditions”. Instead of transparency and control as policy ends in themselves, the quality of life of relational selves and the robustness of the world they construct together and that lies between them depend critically on being treated fairly and not being fooled.

It is interesting to note that the word “trust” blooms in policy documents, showing that the consciousness of the fact that we rely from each other is building up. Referring to trust as if it needed to be built is however a signature of the fact that we are in transition from Modernity to hyperconnectivity, and not yet fully arrived. By approaching trust as something that can be materialized we look at it with Modern eyes. As “consent is the universal solvent” (35) of control, transparency-and-control is the universal solvent of trust. Indeed, we know that transparency and control nurture suspicion and distrust. And that is precisely why they have been adopted as Modern regulatory ideals. Arendt writes: “After this deception [that we were fooled by our senses], suspicions began to haunt Modern man from all sides”[13]. So, indeed, Modern conceptual frameworks rely heavily on suspicion, as a sort of transposition in the realm of human affairs of the systematic doubt approach to scientific enquiries. Frank Pasquale quotes moral philosopher Iris Murdoch for having said: “Man is a creature who makes pictures of himself and then comes to resemble the picture” (89). If she is right—and I am afraid she is—it is of utmost importance to shift away from picturing ourselves as rational subjects and embrace instead the figure of relational selves, if only to save the fact that trust can remain a general baseline in human affairs. Indeed, if it came true that trust can only be the outcome of a generalized suspicion, then indeed we would be lost.

Besides grounding the notion of relational self, the Arendtian concept of plurality allows accounting for interactions among humans and among other plural agents, which are beyond fulfilling their basic needs (necessity) or achieving goals (instrumentality), and leads to the revelation of their identities while giving rise to unpredictable outcomes. As such, plurality enriches the basket of representations for interactions in policy making. It brings, as it were, a post-Modern –or should I dare saying a hyperconnected- view to interactions. The Modern conceptual basket for representations of interactions includes, as its central piece, causality. In Modern terms, the notion of equilibrium is approached through a mutual neutralization of forces, either with the invisible hand metaphor, or with Montesquieu’s division of powers. The Modern approach to interactions is either anchored into the representation of one pole being active or dominating (the subject) and the other pole being inert or dominated (nature, object, servant) or, else, anchored in the notion of conflicting interests or dilemmas. In this framework, the notion of equality is straightjacketed and cannot be embodied. As we have seen, this Modern straitjacket leads to approaching freedom with control and autonomy, constrained by the fact that Man is, unfortunately, not alone. Hence, in the Modern approach to humanness and freedom, plurality is a constraint, not a condition, while for relational selves, freedom is grounded in plurality.

2) From Watchdogging to Accountability and Intelligibility

If the quest for transparency and control is as illusory and worthless for relational selves, as it was instrumental for rational subjects, this does not mean that anything goes. Interactions among plural agents can only take place satisfactorily if basic and important conditions are met. Relational selves are in high need of fairness towards themselves and accountability of others. Deception and humiliation[14] should certainly be avoided as basic conditions enabling decency in the public space.

Once equipped with this concept of the relational self as the canonical figure of what can account for political agents, be they men, women, corporations and even States. In a hyperconnected era, one can indeed see clearly why the recommendations Pasquale offers in his final two chapters “Watching (and Improving) the Watchers” and “Towards an Intelligible Society,” are so important. Indeed, if watchdogging the watchers has been criticized earlier in this review as an exhausting laboring activity that does not deliver on accountability, improving the watchers goes beyond watchdogging and strives for a greater accountability. With regard to intelligibility, I think that it is indeed much more meaningful and relevant than transparency.

Pasquale invites us to think carefully about regimes of disclosure, along three dimensions: depth, scope and timing. He calls for fair data practices that could be enhanced by establishing forms of supervision, of the kind that have been established for checking on research practices involving human subjects. Pasquale suggests that each person is entitled to an explanation of the rationale for the decision concerning them and that they should have the ability to challenge that decision. He recommends immutable audit logs for holding spying activities to account. He calls also for regulatory measures compensating for the market failures arising from the fact that dominant platforms are natural monopolies. Given the importance of reputation and ranking and the dominance of Google, he argues that the First Amendment cannot be mobilized as a wild card absolving internet giants from accountability. He calls for a “CIA for finance” and a “Corporate NSA,” believing governments should devote more effort to chasing wrongdoings from corporate actors. He argues that the approach taken in the area of Health Fraud Enforcement could bear fruit in finance, search and reputation.

What I appreciate in Pasquale’s call for intelligibility is that it does indeed calibrate the needs of relational selves to interact with each other, to make sound decisions and to orient themselves in the world. Intelligibility is different from omniscience-omnipotence. It is about making sense of the world, while keeping in mind that there are different ways to do so. Intelligibility connects relational selves to the world surrounding them and allows them to act with other and move around. In the last chapter, Pasquale mentions the importance of restoring trust and the need to nurture a public space in the hyperconnected era. He calls for an end game to the Black Box. I agree with him that conscious deception inherently dissolves plurality and the common world, and needs to be strongly combatted, but I think that a lot of what takes place today goes beyond that and is really new and unchartered territories and horizons for humankind. With plurality, we can also embrace contingency in a less dramatic way that we used to in the Modern era. Contingency is a positive approach to un-certainty. It accounts for the openness of the future. The very word un-certainty is built in such a manner that certainty is considered the ideal outcome.

4. WWW, or Welcome to the World of Women or a World Welcoming Women[15]

To some extent, the fears of men in a hyperconnected era reflect all-too-familiar experiences of women. Being objects of surveillance and control, exhausting laboring without rewards and being lost through the holes of the meritocracy net, being constrained in a specular posture of other’s deeds: all these stances have been the fate of women’s lives for centuries, if not millennia. What men fear from the State or from “Big (br)Other”, they have experienced with men. So, welcome to world of women….

But this situation may be looked at more optimistically as an opportunity for women’s voices and thoughts to go mainstream and be listened to. Now that equality between women and men is enshrined in the political and legal systems of the EU and the US, concretely, women have been admitted to the status of “rational subject”, but that does not dissolve its masculine origin, and the oddness or uneasiness for women to embrace this figure. Indeed, it was forged by men with men in mind, women, for those men, being indexed on nature. Mainstreaming the figure of the relational self, born in the mind of Arendt, will be much more inspiring and empowering for women, than was the rational subject. In fact, this enhances their agency and the performativity of their thoughts and theories. So, are we heading towards a world welcoming women?

In conclusion, the advent of Big Data can be looked at in two ways. The first one is to look at it as the endpoint of the materialisation of all the promises and fears of Modern times. The second one is to look at it as a wake-up call for a new beginning; indeed, by making obvious the absurdity or the price of going all the way down to the consequences of the Modern conceptual frameworks, it calls on thinking on new grounds about how to make sense of the human condition and make it thrive. The former makes humans redundant, is self-fulfilling and does not deserve human attention and energy. Without any hesitation, I opt for the latter, i.e. the wake-up call and the new beginning.

Let’s engage in this hyperconnected era bearing in mind Virginia Woolf’s “Think we must”[16] and, thereby, shape and honour the human condition in the 21st century.

_____

Nicole Dewandre has academic degrees in engineering, economics and philosophy. She is a civil servant in the European Commission, since 1983. She was advisor to the President of the Commission, Jacques Delors, between 1986 and 1993. She then worked in the EU research policy, promoting gender equality, partnership with civil society and sustainability issues. Since 2011, she has worked on the societal issues related to the deployment of ICT technologies. She has published widely on organizational and political issues relating to ICTs.

The views expressed in this article are the sole responsibility of the author and in no way represent the view of the European Commission and its services.

Back to the essay

_____

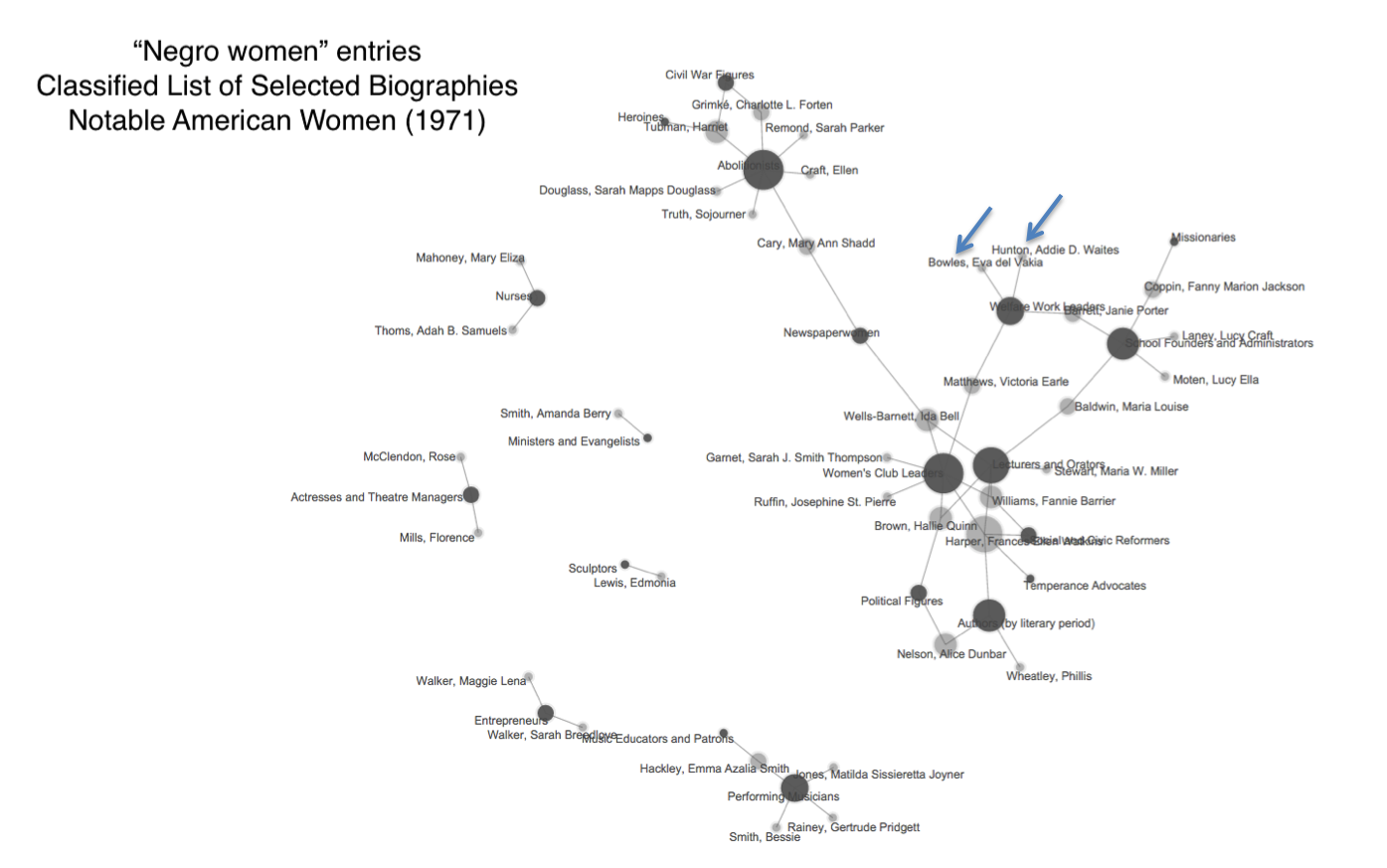

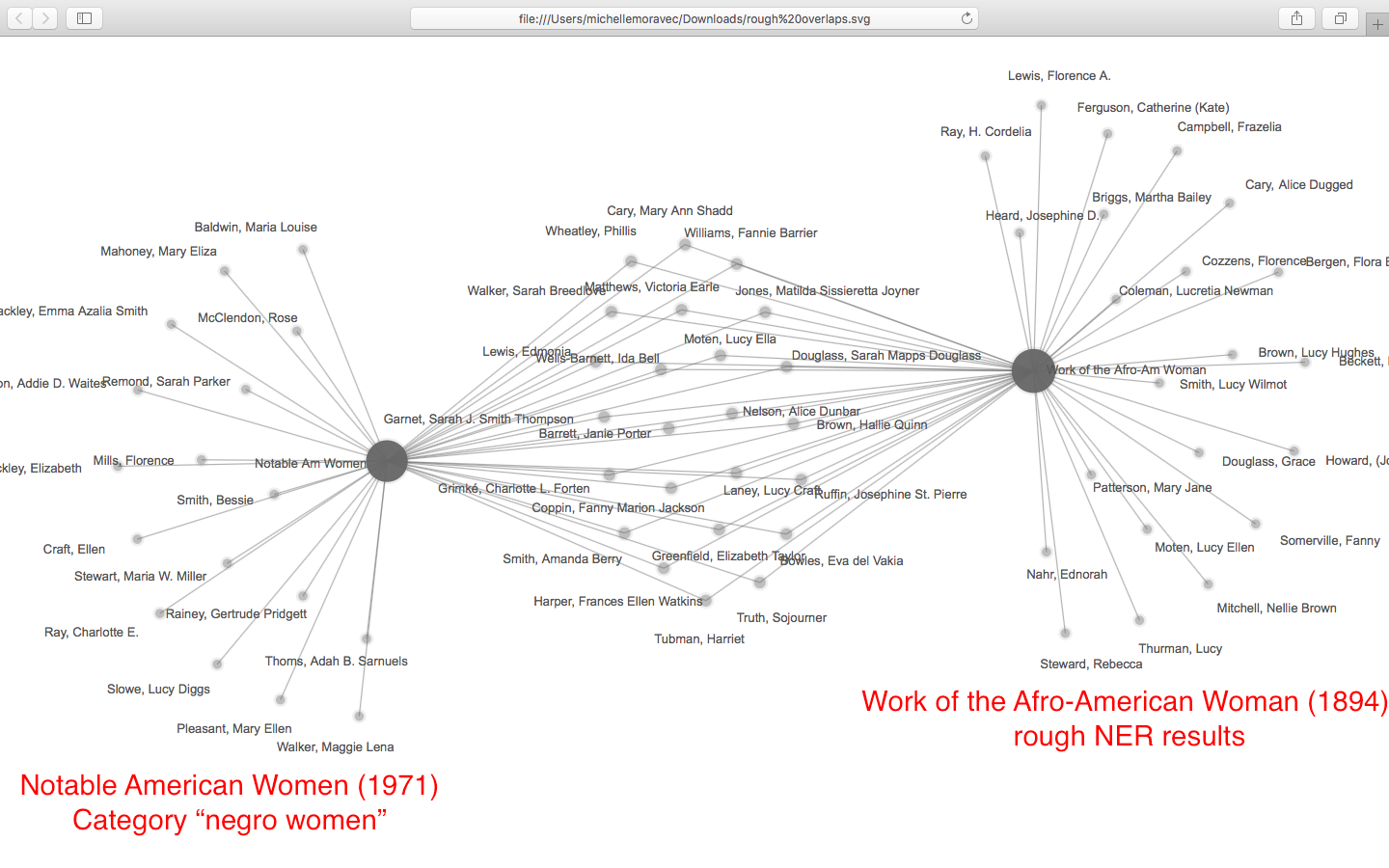

As this poetic quote by Sarah Josepha Hale, nineteenth-century author and influential editor reminds us, context is everything. The challenge, if we wish to write women back into history via Wikipedia, is to figure out how to shift the frame of references so that our stars can shine, since the problem of who precisely is “worthy of commemoration” or in Wikipedia language, who is deemed

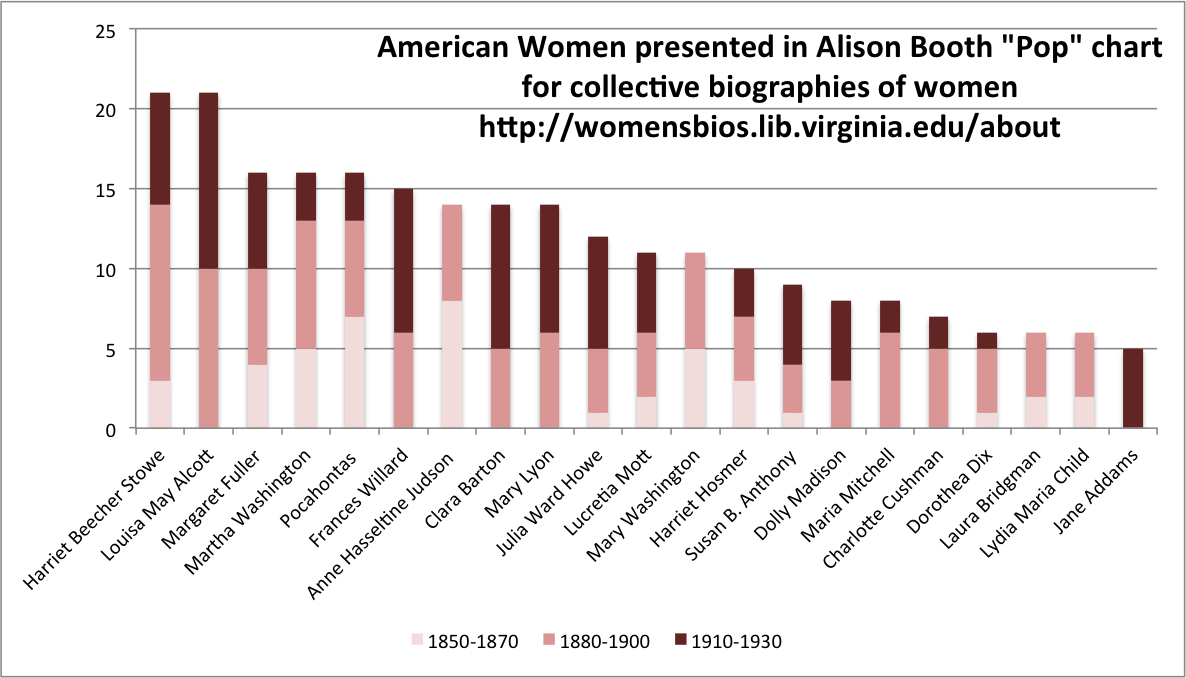

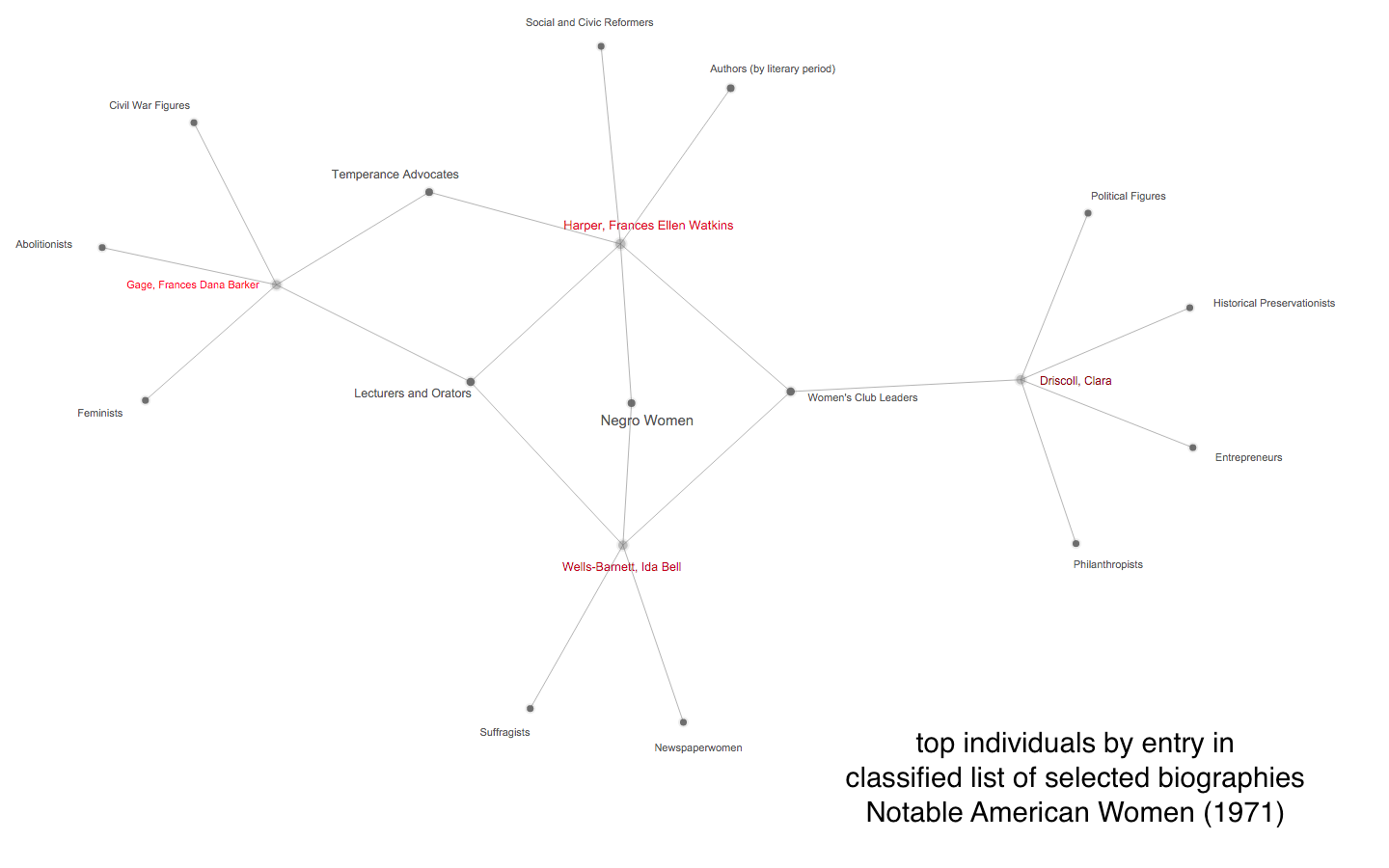

As this poetic quote by Sarah Josepha Hale, nineteenth-century author and influential editor reminds us, context is everything. The challenge, if we wish to write women back into history via Wikipedia, is to figure out how to shift the frame of references so that our stars can shine, since the problem of who precisely is “worthy of commemoration” or in Wikipedia language, who is deemed  mes of prosopography published during what might be termed the heyday of the genre, 1830-1940, when the rise of the middle class and increased literacy combined with relatively cheap production of books to make such volumes both practicable and popular. Booth also points out, that lest we consign the genre to the realm of mere curiosity, predating the invention of “women’s history” the compilers, editrixes or authors of these volumes considered them a contribution to “national history” and indeed Booth concludes that the volumes were “indispensable aids in the formation of nationhood.”

mes of prosopography published during what might be termed the heyday of the genre, 1830-1940, when the rise of the middle class and increased literacy combined with relatively cheap production of books to make such volumes both practicable and popular. Booth also points out, that lest we consign the genre to the realm of mere curiosity, predating the invention of “women’s history” the compilers, editrixes or authors of these volumes considered them a contribution to “national history” and indeed Booth concludes that the volumes were “indispensable aids in the formation of nationhood.”

a review of Frank Pasquale, The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information (Harvard University Press, 2015)

a review of Frank Pasquale, The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information (Harvard University Press, 2015)

a review of N. Katherine Hayles, How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis (Chicago, 2012)

a review of N. Katherine Hayles, How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis (Chicago, 2012)