This article was published as part of the b2o review‘s “Finance and Fiction” dossier. The dossier includes a response to this article by Matthew Potolsky.

Signe Leth Gammelgaard–Flowers Without Meaning: Literary Decadence as Finance Aesthetics

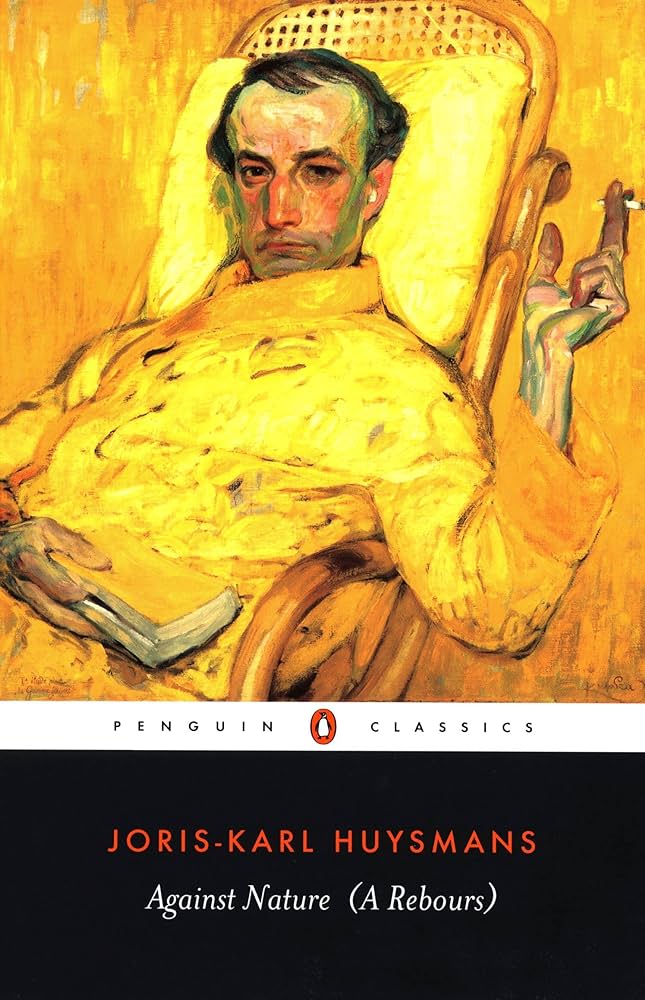

In chapter eight of Joris-Karl Huysmans’s À rebours, the protagonist Jean Des Esseintes muses on his collection of hothouse flowers. The novel is one of the most prominent examples of the literary decadence of the late nineteenth century and such artificially cultivated flowers (as well as the hothouse itself) are a recurrent motif in decadent literature. In his “Préface écrit vingt ans après le roman” Huysmans himself describes the flowers of À rebours as “aphonic” or “mute” (atteinte d’alabie, muette). This imagery of organic flowers, cultivated to mimic artificial flowers as the text explains, conjures up a rather striking scene which epitomizes the decadent aesthetic. This aesthetic can be understood, I want to propose, in light of contemporaneous economic developments, specifically the intensification of the impact of finance – as portrayed in other literary works from the same period, for instance the classic stock-exchange novels of Émile Zola’s L’Argent or Anthony Trollope’s The Way We Live Now.

In what follows, I use Giovanni Arrighi’s model of financial expansion as a recurrent phenomenon throughout the history of capitalism. The final decades of the nineteenth century were one period of such expansion, where a major part of the money capital became invested rather in financial instruments and assets than in material production. The late nineteenth century, then, in some ways productively mirrors our current period of financialization which began in the 1970s, even if it is not understood as the same period of financial expansion in Arrighi’s framework (Arrighi 2010, 6–7). The significant rise in the impact of finance in the latter half of the nineteenth century occurred especially in the imperial centers of France and Britain. This rise has been portrayed in various ways in the literature of the period, and particularly within the framework of the realist novel, a subject of numerous studies in the past decades. In new economic criticism, the Victorian period specifically has been the focus of several important works, like Mary Poovey’s Genres of the Credit Economy and Catherine Gallagher’s The Body Economic. However, less attention has been paid to the literary fin de siècle, the stylistic developments of decadence and aestheticism.

In this article, I propose to outline some key parallels between the aesthetic traits of these movements and the concurrent development in the economic system, in particular the steady rise of financial instruments, trades, and structures. I start by analyzing the core decadent aesthetics traits as opposed to earlier realist aesthetics, and then contextualize these by their relationship to the development of Ferdinand de Saussure’s structural linguistics. I then show how Saussure’s linguistics parallel another theoretical shift, namely the marginal revolution in economic theory. Finally, I will examine how these three shifts respond to larger economic trends in the period; specifically, the switch from an emphasis on material production to an emphasis on financial investment and instruments.

The parallels between linguistic and economic systems have been illuminated before. My central point in this article is that the decadent aesthetics, specifically, render a representational shift in a way that generates an existential and perceptive view on this period and on its changes in both economics and language; namely a loss of meaning. It also presents a strategy of response to such a situation in the form of a renegotiation of the relationship between signs and material reality.

The mute flowers of decadence

Huysmans’s À rebours is a peculiar novel. While it has often been described as plotless,[1] the frame of the narrative in fact provides a simple storyline and the epitome of a decadent one at that. As the last scion of an old, degenerated family, Jean Des Esseintes delves into various extreme and debauched lifestyles before he, weary with the depraved Paris life, retreats to a house he buys outside the city, in Fontenay. The majority of the book details his decorating of this house and his aesthetic choices and sensory experiences with various stimulants: art, literature, colors, interior design, gemstones, flowers, music, perfumes, culinary delights. Finally, however, his body is worn out by his excessive enjoyment, and he is urged by his doctors to return to a normal life and “to enjoy himself, in short, like other people” (Huysmans 2009a, 173).

The flower chapter outlines very clearly how these aesthetic experiences work. It opens by stating that, though Des Esseintes has “always adored flowers” he is now only interested in one kind: the hothouse flowers. The passage outlines this development: after his love of real flowers, he had, in his previous life in Paris and in line with his “natural inclination towards artifice,” amassed a large collection of artificial flowers “faithfully imitated thanks to the miracles of gums and threads, percalines and taffetas, papers and velvet” (Huysmans 2009a, 72–73). However, with his move to Fontenay, a new phase emerges and the narrator comments regarding the artificial flowers: “He had long been fascinated by this wonderful art-form; but now he dreamt of planning a different kind of flora. After having artificial flowers that imitated real ones, he now wanted real flowers that mimicked artificial ones” (Huysmans 2009a, 73). As such, the hothouse blooms become an almost parodical expression of a crisis of representation, with plants cultivated artificially in “the carefully measured warmth of stoves” (Huysmans 2009a, 72), to look like fake ones, that in turn look like real ones.

Des Esseintes tours the horticulturalists of the area of Fontenay and orders a collection of plants. When they arrive, the narrative describes how some “were extraordinary, pinkish in colour, like the Virginal which looked like it had been made out of oilcloth or court plaster; some were entirely white, like the Albany, which could have been cut from the transparent pleura of an ox,” some “mimicked zinc, parodying pieces of punched metal that had been dyed Emperor green and stained with drops of oil-paint and splashes of red and white lead” (Huysmans 2009a, 73–74). As such, the sensory impression of the flowers takes center stage: how they look and what they look like. Conversely, the narrative does not in any way refer to the symbolic language of flowers, that is, metaphoric, traditional or symbolic meanings of love, hope or virtue.

This point is at the center of both Suzanne Braswell’s and Robert Ziegler’s analysis of the hothouse flowers of À rebours. Ziegler underscores, by reference to Huysmans’s own preface from twenty years later and thus written after his conversion to Catholicism, precisely the muteness of the flowers (Ziegler 2015, 51–52). In this “Préface écrit vingt ans après le roman,” Huysmans notes:

It would have been difficult, in that novel, to endow an aphonic flower, a mute flower, with speech, for the symbolic language of plants died with the Middle Ages and the exotic flora dear to Des Esseintes were not known to the allegorists of that age. (Huysmans 2009b, 190)

Ziegler’s analysis portrays this muteness through comparison to Huysmans’s later work, in particular the novel La Cathédrale, where the flowers and plants have become re-endowed with meaning through the work of religion, through Huysmans’s conversion. However, as the quotation shows, the mute flowers adhere to a modern condition, albeit the modernity that began already with the end of the Middle Ages.

Braswell’s analysis takes a broader view on this modernity and traces discourses on the symbolic language-of-flowers. Her reading stresses specific changes in these discourses precisely towards the end of the nineteenth century and she argues that, while Stéphane Mallarmé’s work nuances and elaborates the earlier traditions, the flowers in À rebours in turn “attack the tradition and parody its discourses, particularly those promoting the healthful and chaste aspects of horticulture” (Braswell 2013, 76, 83). The point that emerges is that these elaborate, exotic, and artificially cultivated plants have become such a perverse manifestation that they no longer signify; rather, they look like various forms of dying or diseased flesh, rendering distinct “necrotic dimensions” as Braswell terms it (Braswell 2013, 83). In the novel, this is seen in the passage on the next round of flowers to arrive:

they simulated the appearance of fake skin scored by artificial veins; and the majority, as though eaten away by syphilis and leprosy, exhibited livid flesh marbled with roseola and damasked with dartres; others were the bright pink of scars that are healing, or the browning tint of scabs in the process of forming; others were blistering from cautery or puffing up from burns (Huysmans 2009a, 74).

This imagery of decaying organisms, diseased tissue and putrefying flesh, however, links the floral passages to linguistic developments as they are described both in À rebours and in the movement of decadence more generally. In a previous chapter Des Esseintes meditates on his literary preferences, specifically among the Latin authors of the Roman decadence. Here, the narrator explains that:

Des Esseintes’s interest in the Latin language remained undiminished, now that it hung like a completely rotted corpse, its limbs falling off, dripping with pus, and preserving, in the total corruption of its body, barely a few firm parts, which the Christians took away to steep in the brine of their new idiom. (Huysmans 2009a, 31)

The advent of Christianity is given a key role in the development where the language of the Pagan Rome “decomposed like venison,” in fact “falling apart at the same time as the civilization of the Ancient World crumbled into dust, at the same time as the Empires, rotted by the putrefaction of the centuries, collapsed under the onslaught of the Barbarians” (Huysmans 2009a, 28).

The decadence of a civilization is thus matched by the decadence of its linguistic forms – forms that are in turn described in the same language as the appearance of the mute flowers, the flowers that have lost their metaphorical meanings. However, the idea of a decomposing organism of language is not specific to Huysmans. Indeed, in his Decadence and the Making of Modernism, David Weir comments on an earlier example of decadent criticism, namely Theophile Gautier’s essay on Baudelaire from 1868 (Weir 1995, 88–89). In this essay, Gautier, similar to Des Esseintes’s reflections, connect the decadent Latin literature to the literature of his own time. Moreover, he examines Baudelaire’s relationship to the “masters of the past,” in whom he cannot find an adequate model for his own period, since these masters had been born “when the world was young,” and “when as yet nothing had been expressed” (Gautier 1908, 38). Gautier writes further:

The great commonplaces that form the main stock of human thought were then in their first flush, and sufficed for simple geniuses addressing a people yet childish. But by dint of being repeated, these general poetic themes had become worn, like coins that have been too long in circulation and have lost their sharpness of outline; besides, life has become more complex, contains more notions and ideas, and is no longer sufficiently reproduced in artificial compositions inspired by the spirit of another age. (Gautier 1908, 38)

The metaphor of the worn-out coin instantly establishes a parallel between the representational system of money, and that of language. In the original French the wording is “perdent leur empreinte” rather than “lost their sharpness of outline”, so the image underscores how the coins have gradually lost their imprint, their stated value, effecting a mismatch between the form and content of the coin: its “meaning” has been skewed. The passage thus describes a shift in representation, and Gautier links this shift to a decadent Zeitgeist.

With recourse to Roland Barthes’s “L’Effet de réel,” this gap between form and content can be inscribed in a larger narrative. While Barthes’s short essay revolves mainly around his conception of the reality effect, towards the end of the text he speculates on a more general meaning of this particular effect. He argues that realism, conceived around the notion of this reality effect, is in fact a forerunner to the problematized representation of his own time, described in Barthes’s words as a “disintegration of the sign – which seems indeed to be modernity’s grand affair” (Barthes 2006, 234). Furthermore, he states, “the goal today is to empty the sign and infinitely to postpone its object so as to challenge, in a radical fashion, the age-old aesthetic of ‘representation’” (Barthes 2006, 234).

Barthes describes the concept of the reality effect, key to his understanding of realism, in a way that aligns with the decadent aesthetic seen in Huysmans’s flowers, namely that of a mute, unsignifying materiality. The reality effect thus invokes the material world not to signify anything specifically in a narrative context but merely to denote the reality of the stated utterance. Barthes writes:

Semiotically, the “concrete detail” is constituted by the direct collusion of a referent and a signifier; the signified is expelled from the sign, and with it, of course, the possibility of developing a form of the signified, i.e., narrative structure itself. […] in other words, the very absence of the signified, to the advantage of the referent alone, becomes the very signifier of realism: the reality effect is produced, the basis of that unavowed verisimilitude which forms the aesthetic of all the standard works of modernity. (Barthes 2006, 234)

What Barthes describes here is essentially a “flat” material world, a disenchanted and meaningless observation of the purely material properties. However, Barthes’s analysis identifies this aesthetic through the conception of the “absence of the signified.” To understand this in more depth, I now turn to Ferdinand de Saussure’s original conception of the dual sign consisting of signifier and signified.

Saussure’s structuralism and the disintegration of the sign

Saussure’s most famous work is presented in the Cours de linguistique générale, a work based on a series of lectures given by him between 1906 and 1911 and compiled from notes by Charles Bally and Albert Sechehaye. Though Saussure never published this work himself, the course has had a large significance for various fields outside of linguistics and, according to letters and notes that have since been found, Saussure started thinking about issues in general linguistics already in the final decades of the nineteenth century – in other words, contemporary to the decadent movement (Culler 1976, 15). In fact, economics seems to have been an inspiration for the ways in which Saussure wanted to redefine linguistics, and in the Cours he refers to the content of the linguistic sign as its “value,” but only insofar as the signified, the concept or meaning of a sign, has a value exactly because it is part of a system of language and compared to other values and signs (Saussure 2011, 114–17).

The Saussurian innovation resides largely in the dual nature of the sign: it consists of two parts, namely signifier and signified. According to Saussure, language is not made up of connections between signs and the material world but is rather a system of signs comprised by signifiers and signifieds. The signifier is the sound-image (the image of sound exists even if it is not pronounced) and the signified is the mental concept, meaning what we think of when we hear the sound-image. The relation between these two parts of the sign is arbitrary; though there are some onomatopoetic words, in general the relation between a specific word and its mental concept is random. Saussure refers specifically to the signified as the “meaning” or “content” of the sign, which then has value in a system (Saussure 2011, 65–78, 114–17). As such, the signified also holds the mediating function of language, the process by which we interpret arbitrary signifiers into meaningful content which we can then draw upon in our interaction with the physical world. When the reality effect in the decadent aesthetics is conceived as a “direct collusion” between referent and signifier, a lack of a proper signified, it signals a loss of narrative meaning.

However, for Saussure this understanding also enables a new conception of linguistics itself. Language can be understood as a structure or system in which each sign has meaning only in relation to other, different signs. The material world – termed “the referent” in semiotics – lies beyond the scope of linguistics according to Saussure, as it is the structure of language that should be studied in this discipline. Hence, structural linguistics brackets the idea of an underlying material reality: Linguistics should thus not be concerned with the connection between referent and signified, or for that matter between referent and signifier, but should only study linguistics as a differential relationship between signs. It is the difference of one word from that of another that gives it its meaning, not its connection to any actual thing.

Barthes’s analysis shows a very explicit use of Saussure’s dual sign: the duality of signifier and signified enables an analytical description of what is happening when representation becomes problematic, when the materiality becomes mute and meaningless. The conception that the “form of the signified” is the narrative structure itself is, moreover, interesting in the sense that, while Barthes’s examples in the essay refers to realist works that do have a storyline or plot, À rebours is often described as a novel without a plot. While it is a feature of realism (and only realism) in Barthes, I argue that the reality effect is a core component of the estrangement of the mute flowers in À rebours. In Huysmans’s novel (and in decadence more generally) the reality effect becomes not only a specific aesthetic strategy but the whole point of the narrative: it is central to the loss of meaning that drives the novel.

Following the work of scholars like Mary Poovey and Jean-Joseph Goux, I would now like to contextualize this shift from the meaningful narrative of realism to a decadence describing a loss of meaning beyond Saussure’s contemporaneous structural linguistics, namely in a parallel to the economic sphere (which is present in Saussure’s theory, as I have already shown).

The liquid values of marginal utility

Around 1870, the field of political economy spawned a significant new set of ideas that, similar to the decadent literature, augurs a new relationship between material reality and language or signs, in this case the language of values and economics. Independently of each other, three theorists in three different countries simultaneously developed theories based on the notion of marginal utility: W. Stanley Jevons in England, Léon Walras in Switzerland, and Carl Menger in Austria. The basic tenet of these theories is the idea that the value of anything can be determined by the thing’s marginal utility, that is, the utility of the “last available item” of a specific commodity. The amount and availability of something thus becomes the central parameter, because its utility will decrease with the amount available. Thus, when there is plenty of water, even though it is necessary for survival, its value will be low. On the other hand, when water is a scarce resource, its value will be incredibly high. The value of a commodity is thus expressed by the commodity’s exchange value, its price in a market (Jevons 1999, 143). The notion of value in this way becomes tied to the concept of scarcity.

With the marginalist perspective the value of something thereby shifts away from the earlier focus on the cost it takes to produce it, and towards the intensity of the desire that it can create – essentially the shift goes away from production and towards consumption, and this has consequences for the relationship between prices – the monetary sign – and material world of commodities. To understand precisely what the shift in economic theory entails and how it parallels decadent aesthetics and structural linguistics, a brief review of Marx’s notion of value is useful.

While the earlier field of political economy spearheaded by Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Thomas Robert Malthus, and Karl Marx had many disagreements, the prior theories all revolved around the concept of a labor theory of value. Marx divided the concept of value into three separate notions, namely “use value”, “exchange value”, and “value” itself (Marx and Engels 1996, 45–51). The latter one is at the core of his theory of capitalism as it elucidates how the exchange between capitalist and worker takes place. Capitalism, according to Marx, is the specific situation where the worker has nothing to sell but his labor power, and where the capitalist, conversely, holds the means of production including the necessary capital to establish a production of some commodity. Labor power is also a commodity and it is the only commodity a worker can sell. Contrary to other commodities, however, labor has the specific feature that it can produce more value than it takes to reproduce it – basically, a laborer can work more and produce more than what is required for her own reproduction and survival. This “more” is what Marx defines as surplus value, and the relationship between capitalist and worker is defined by the fact that the surplus value falls to the capitalist. While the basic level of reproduction is historically and geographically variable, the central mechanism remains the same, even if the worker is granted higher wages for her own reproduction (Marx 2016, 885).

However, the way Marx links the concept of labor time to value is central, because it shows how the whole economic system is linked to the material needs of a given society, and thereby anchors the theory in material reality. For labor to be the basic universal equivalent, namely the thing that enables the exchange of two qualitatively different commodities, Marx introduces the concept of abstract labor time. This concept expresses the amount of labor time necessary for a given society to uphold its current state and it is thus an abstract concept, not possible to measure in any exact way. The value of a given commodity is the labor time it takes on average to produce it, expressed as a fraction of the total socially necessary labor time of a society. Thus, the value of a specific commodity is not larger if it is produced by a slow worker than a similar one produced by a fast worker (Marx and Engels 1996, 48–49). As such the concept of abstract labor time both lodges the labor theory of value in a concrete material reality (namely the necessary amount of labor to sustain a society) and gives a commodity an underlying value described as a part of this necessary labor. It is this relationship to reality that changes with the new economics, and that change can in turn be related to the shift from realist narrative language to decadent mute description.

According to Marx the exchange value will over time stabilize around the actual value of something. Indeed, he states in volume one of Capital that “the labour time socially necessary for their production forcibly asserts itself like an over-riding law of Nature” (Marx and Engels 1996, 86). Thus, while exchange values (that is, the prices) does figure into Marx’s theoretical edifice, they function mainly as expressions of the underlying value that has a relationship to societal value as a whole – and these expressions can be more or less representative or accurate (Marx 2016, 460). In the marginal utility theory, this calculation of labor time vanishes and production cost is assigned a different role, namely as a component of a cost-benefit analysis on the part of the producer. In marginal utility theory, also called neoclassical economics, value expresses only intensities of desire – the desire for the pleasure of consuming something versus the pain of acquiring it (the labor necessary for obtaining it), and relative to other things that can be acquired for the same amount of “pain.” These calculations of pleasure and pain then meet up with the similar calculations of other actors in a marketplace, and generates a price: the desire of the buyer for consumption meets the “pain” that the producer has put into creating it and therefore needs compensation for. The price becomes an exact expression of value, because value is no longer defined as some underlying quality, but only as the price that a good can obtain in a marketplace (Gallagher 2008, 126–27).

Jean-Joseph Goux expands on this point and claims:

Any questioning of “value” beyond a state of equilibrium momentarily offered by a market, or auction, of pure competition becomes a futile, useless, metaphysical and unscientific pursuit. For Walras, Karl Marx, like Adam Smith, remains a metaphysician; both Marx and Smith seek a unique and enduring principle that would fix value, the universal law regulating the exchange of products, which they find in the time of labour. (Goux 1997, 163)

I have dwelled at some length on this precise difference because the central shift regards a conception of labor and of the material reality to which prices refer. Thus, when we saw in the decadent literature a changed relationship between the referent and the signifier, expressed as a loss of the meaning – a loss of the signified – here we have a system of thought that is no longer interested in the relationship between signified and referent. Signs refer only to other signs in the system. As Goux portrays it, there is no longer any fixed point to which value refers, no concrete reality. Value only expresses wants, and these wants fluctuate according to scarcity (real or artificial), usefulness and, last but not least, the ability of something to create desire. Goux describes this conception of value as the “stock-exchange paradigm” as it fits with the way the stock exchange works. For Goux, this is not merely a change in economic theory, but a development that describes modernity as such, and like Barthes’s idea of “modernity’s grand affair,” it concerns a specific change in the way that signs work (Goux 1997).

However, while Saussure’s linguistics and marginalist economics both bracket the relationship of signs to the material world, the decadent aesthetics present a very precise way that the loss of a connection between societal values and material reality can take on an existential dimension and be perceived as a loss of meaning tout court. A few decades after Gautier’s aforementioned text, in 1881, a different critic of decadence, namely Paul Bourget, examines the relationships between linguistic and societal meaning through the example of Baudelaire in relation to decadence. The parallel Bourget sees between these two registers is through the image of the organism. A decadent society, he holds, is characterized by a state of affairs where the individual units, the smaller cells and lesser organisms, become independent and no longer work by subordinating their energy to the total organism. Same principle for language, he claims:

The very same rule governs the development and the decadence of another organism, language. A decadent style is one in which the unity of the book falls apart, replaced by the independence of the page, where the page decomposes to make way for the independence of the sentence, and the sentence makes way for the word. There are innumerable examples in current literature to corroborate this hypothesis and justify this analogy (Bourget 2009, 98).

This quotation, often cited and used as definition for the decadent style, describes fragmentation and lack of any conception of totality or coherent whole, and the text describes this “anarchy” as a state of decline of both the organism of society and that of language. With the parallels between the new economic thinking and the new linguistic theory of the final decades of the century, falling apart and lack of unity of the decadent aesthetics can be understood in relation to shifts in the economic sphere. However, while the marginalist theory shows a system that becomes unlinked to the material necessities of a given society’s reproduction, it does not explain what happened in the actual economy of the period and how that relates to literary expression. To explain this link, and why it results in an aesthetics of fragmentation and disunity, Mary Poovey’s work is more instructive than Goux’.

In Genres of the Credit Economy (2008), Poovey expounds on the parallels between money, economics, language, and literature in a historically grounded perspective, reading two centuries of British literary and economic history in conjunction. By doing so, Genres makes a key point about the historical dynamic between these two systems. In Poovey’s account, they do not only display parallel features, they also actively influence one another. Concerning specifically what Poovey terms the “problematic of representation” – that is, “the gap that separates the sign from its referent or ground (of value or meaning), whether the gap takes the form of deferral, substitution, approximation, or obscurity” (Poovey 2008, 5) – she states:

Unlike most Literary critics, however, I do not present the problematic of representation as a property of all systems of representation. Instead, I argue that representation becomes problematic—it presents problems that are both social and epistemological—only at certain times and under conditions that are historically and socially specific. A system of representation is experienced as problematic only when it ceases to work—that is, when something in the social context calls attention to the deferral or obfuscation of its authenticating ground. (Poovey 2008, 5–6)

The thing in the social context that can cause this awareness is mainly economic events, for instance crises, crashes, bubbles, and mania. Thus, Poovey foregrounds the notion that the representational function is historically variable, at the same time as she stresses the connection between linguistic and monetary systems. While Poovey does not operate with the Saussurian concepts of signifier and signified but rather conflates the notions of signified and referent in the above passage, it is clear that her point relates to the problem of materiality and meaning. Like the shifts related to decadent aesthetics, Saussure’s linguistics, and Goux’s reading of marginal utility theory, the sign begins to work differently. Huysmans’s novel shows, indeed, how such crises of representation can be interpreted through an aesthetics of the lost signified, in Barthes’ words the “direct collusion of a referent and a signifier.”

À rebours thus portrays a situation in which its protagonist experiences a ‘mute referent’ in place of a narrative signified for the flowers. However, for the reader of the novel the words themselves naturally still have a meaning – they still have a signified. Telling the story of a lost signified for the character – the story of a mute and meaningless materiality – thus becomes the narrative signified for the reader: the text becomes a meaningful expression about the loss of meaning in both a linguistic and an existential sense. Furthermore, while these flowers are no longer endowed with metaphorical meaning, they still look like something, namely decaying bodies, an image which is also used to describe the linguistic disintegration of representation in both Huysmans and elsewhere. In so far as these descriptions of flowers still do signify, they signify on the one hand the mute referent in a Barthesian sense, and on the other connote an imagery of disintegrating organisms. In both cases, they signal a shift in representation, a shift in the mediating function of the signified. With Poovey’s notion of economic events as a trigger for such representational issues in mind, I will now turn to the actual economic changes of the period.

The late nineteenth century crisis

The final decades of the nineteenth century saw an economic situation in the old European empires that in some central ways matches that of the US today: repeated crashes and volatile economy, a huge increase in the impact of the financial sector, staggering growth and a cut-throat price competition. In terms of imperial affairs, this period is known for the “scramble for Africa,” the intense round of colonization of African territories which increased the European control from 10 percent to 90 percent over two decades. Literary scholars and historians alike have described the massive boom in financial instruments and stock-companies, accompanied both by new legislation and the pressure for better information through a reliable, critical press (Kornbluh 2014, 1–2; Henry and Schmitt 2009; Poovey 2002, 17–18; 2008, 274; Taylor 2014). According to Giovanni Arrighi’s The Long Twentieth Century, the year 1870 augurs the financial phase of the period of capitalist development that he terms the British cycle, and this financial phase followed an initial phase of material expansion (characterized by increased production, colonial ventures and intensification of trade). The financial phase of this period was characterized by capital agencies withdrawing from investment in material production and trades, and concentrating instead on banking, money trades and finance, and such change indicates the decline of a period of capitalist development in Arrighi’s model. Drawing on the work of Fernand Braudel, Arrighi states that “financial expansions are taken to be symptomatic of a situation in which the investment of money in the expansion of trade and production no longer serves the purpose of increasing the cash flow to the capitalist stratum as effectively as pure financial deals can” (Arrighi 2010, 9). The late nineteenth century financialization thus spelled the end of the British (and French) cycle while the United States became the new power center, breeding new material growth.

The onset of literary decadence, the shift towards the financial phase, the invention of a new conception of economic value and modeling, and the birth of a new linguistic theory thus all center around these decades and the 1870s specifically. At the same time, these four events all display issues in the functioning of the signified: the role of the signified as mediator to the referent is challenged by the way that the referent appears irrelevant in marginalism and in structural linguistics, and the role of the signified is in turn replaced by images of a mute material referent in the later forms of realism and in the movement of decadence especially. However, I have yet to show the role of the signified in financialization. In order to do so I will turn once more to Marx’s writings.

In the Economic Manuscript of 1864–1865 (his only full draft for volume III of Capital), Marx analyses the dynamics of loan capital and interest and describes the basic mechanism through the model of capitalist production and surplus value. Where the typical cycle for capitalist production is expressed by the formula M–C–M’, where an amount of money (M) is used to produce commodities (C), which can then be sold for a larger amount of money (M’ = the original amount + the surplus value), the expression of loan capital (that is, investments) becomes M–M’ to the lender-capitalist, where the surplus money derives from the interest paid on the loan. What disappears from the formula, then, is precisely the materiality of the commodity and, in Marx’s understanding also therefore the embodied abstract labor power required to produce said commodity. Instead, the formula expresses an amount of money that appears to be growing by itself over time. In chapter 5, part 1, he discusses the expression that the rate of interest is the “price of money,” calling this price a “purely abstract form, completely lacking in content” (“rein abstrakte und inhaltslose Form”) (Marx 2016, 458; Marx, Engels, and Müller 1992, 4:426). What is meant by this lack of content is outlined through a comparison to the prices of regular commodities governed by the following rule:

If supply and demand coincide, the market price of the commodity corresponds to its price of production, i.e., its price is then governed by the inner laws of capitalist production, independently of competition, since fluctuations in supply and demand explain nothing but divergences between market prices and prices of production (Marx 2016, 460).

Marx goes on to emphasize, then, that no such divergences exist for the “price” of capital (that is, the interest) as there simply “is no natural rate of interest. What is called the natural rate of interest means rather the rate established by free competition” (Marx 2016, 460). Marx thus outlines that the interest, the price of capital, is equal to what came to be understood as value by the marginalists, a value determined by competition and with no ties to the amount of labor needed to reproduce a given society. It is value in the sense that Goux terms the stock-exchange paradigm, and what is omitted from this conception is the labor of production, embodied in commodities, and which in Marx’s schema can be seen as the signified of money. I therefore suggest that these shifts–the shift of aesthetics, the shift of linguistics, the shift of economic theory–are in turn related to the larger shift from a society based on the production and commerce of commodities produced by labor power, to the commerce of various forms of financial products. Arrighi stresses this point of going from Marx’s theoretical model to a conception of historical phases and explains:

Marx’s general formula of capital (MCM’) can therefore be interpreted as depicting not just the logic of individual capitalist investments, but also a recurrent pattern of historical capitalism as world system. The central aspect of this pattern is the alternation of epochs of material expansion (MC phases of capital accumulation) with phases of financial rebirth and expansion (CM’ phases). In phases of material expansion money capital “sets in motion” an increasing mass of commodities (including commoditized labor-power and gifts of nature); and in phases of financial expansion an increasing mass of money capital “sets itself free” from its commodity form, and accumulation proceeds through financial deals (as in Marx’s abridged formula MM’). Together, the two epochs or phases constitute a full systemic cycle of accumulation (MCM’). (Arrighi 2010, 6)

This historical shift might perhaps also be used to understand why the theoretical framework of Capital, with its pinnacle of the labor theory of value, was not, after the 1870s, the most adequate framework to explain market dynamics, because, in a phase dominated by finance capital, the marginal utility theory more adequately explains how value is conceived since the economy is no longer organized mainly around material production. However, invoking the larger framework of the world systems as Arrighi does, reinscribes the finance capitalist systems as phases in a larger dynamic. And within this dynamic, what happens in phases of financial expansion, is that the signified of money (commodities and labor), disappears from view. We then get two new theories that explain how sign systems begin to work, and we get a decadent aesthetics that tries to renegotiate a material world that the theories are no longer concerned with.

The decadent literature, then, does not simply decouple language from the material realm like the structural linguistics or marginalist economics, but presents, rather, a different kind of connection to it. Most decadent works place a premium on the concept of sensory and sensual enjoyment, epitomized in Des Esseintes’s practices as an aesthete. While on the one hand, this enjoyment undeniably parodies consumption by taking it to the utter extreme, it can also be interpreted as an attempt to reconnect with the material world, to reinvent “meaning” as “sense” in a situation that is no longer mediated by the previous social functioning of the signified. The material world appears meaningless but at the same time menacing, strange, and incomprehensible, accessible only by the sheer sensory properties it invokes. And thus, these properties must be examined, dealt with, experienced, in “a new Hedonism” as it is termed in Oscar Wilde’s The picture of Dorian Gray (Wilde 2006, 22). The success of this “solution” however, is questionable, as most of the decadent works end on a somber note. Thus, when Des Esseintes ponders his return to normal society the book ends with his prayer to a divinity he fails to believe in: “Lord, take pity on the Christian who doubts, on the unbeliever who longs to believe, on the galley-slave of life who is setting sail alone, at night, under a sky no longer lit by the consoling beacons of the ancient hope” (Huysmans 2009a, 181).

Conclusion

While previous research has in various ways established parallels between language and money or economics, I have focused on decadent aesthetics because they show a very precise way that large economic changes in society can impact the ways in which we perceive the social and material world. They suggest, in particular, one way in which the subject can react to a phase of financial intensification: by a rather fetishistic relationship to materiality. In the decadent aesthetic, the properties of things in the material world become defining for our experience of them, rather than their social meaning, function, or usefulness. In decadent novels, this is also linked with excessive consumption, even hedonism. As there can no longer be found any social meaning, the only grounding principle for the subject is the sensory experience of the material world. This world, however, lacks any substantive ordering principle and becomes an excess of impressions.

By establishing the structural parallel between literary decadence and the economic and financial developments of the period, I am also suggesting that the free-floating, differential values of the Saussurian linguistics, and of the neoclassical economics, are responses to the same global developments in the mode of production. The final point I want to emphasize is that decadent literature’s way of responding to the changes I have discussed, differs from the theoretical responses in linguistics and economics by insisting on the relevance of sensory experience and materiality. In a sense, À rebours is trying to figure out what to do with a materiality that can no longer really be understood through the models we know, and it describes the loss of tethering that this social fragmentation results in. The protagonist becomes, quite literally, unhinged from a topsy-turvy world in which meaning remains at large.

Signe Leth Gammelgaard is a postdoc in comparative literature at Lund University. Her research focuses on the intersection of literary and economic history.

References

Arrighi, Giovanni. 2010. The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times. 2nd ed. London; New York: Verso.

Barthes, Roland. 2006. “The Reality Effect.” In The Novel: An Anthology of Criticism and Theory, 1900-2000, edited by Dorothy J. Hale, 229–34. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Bourget, Paul. 2009. “The Example of Baudelaire.” Translated by Nancy O’Connor. New England Review (1990-) 30 (2): 90–104.

Braswell, Suzanne. 2013. “Mallarmé, Huysmans, and the Poetics of Hothouse Blooms.” French Forum 38 (1/2): 69–87.

Culler, Jonathan. 1976. Saussure. Fontana Modern Masters. London: Harvester Press.

Gallagher, Catherine. 2008. The Body Economic, Life, Death, and Sensation in Political Economy and the Victorian Novel. Princeton University Press.

Gammelgaard, Signe Leth. 2020. “Indebted Bodies: Debt and Decadence in the Nineteenth-Century Novel.” PhD dissertation. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg.

Gautier, Theophile. 1908. The Works of Theophile Gautier, Vol. 23, Art and Criticism: The Magic Hat. George D. Sproul. http://archive.org/details/worksoftheophile028595mbp.

Goux, Jean-Joseph. 1997. “Values and Speculations: The Stock Exchange Paradigm.” Cultural Values 1 (2): 159–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/14797589709367142.

Henry, Nancy, and Cannon Schmitt, eds. 2009. Victorian Investments: New Perspectives on Finance and Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Huysmans, J.-K. 2009a. Against Nature. Translated by Margaret Mauldon. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

———. 2009b. “Appendix: Preface ‘Written Twenty Years after the Novel.’” In Against Nature, by J.-K. Huysmans, translated by Margaret Mauldon, 183–97. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Jevons, William Stanley. 1999. “Brief Account of a General Mathematical Theory of Political Economy.” In Sources: Notable Selections in Economics, edited by Belay Seyoum and Rebecca Abraham, 1. ed, 141–46. Guilford, Conn: Dushkin/McGraw-Hill.

Kornbluh, Anna. 2014. Realizing Capital: Financial and Psychic Economies in Victorian Form. First edition. New York: Fordham University Press.

Marx, Karl. 2016. Marx’s Economic Manuscript of 1864-1865. Edited by Fred Moseley. Translated by Ben Fowkes. Historical Materialism Book Series 100. Leiden ; Boston: Brill.

Marx, Karl, and Frederick Engels. 1996. Marx & Engels, Collected Works. Volume 35. Karl Marx – Capital Volume I. Collected Works 35. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Marx, Karl, Friedrich Engels, and Manfred Müller. 1992. Gesamtausgabe. Abt. 2. Das Kapital und Vorarbeiten Bd. 4. Ökonomische Manuskripte 1863 – 1867 / Karl Marx Apparat: Teil 2. Vol. 4. Berlin: Dietz.

Poovey, Mary. 2002. “Writing about Finance in Victorian England: Disclosure and Secrecy in the Culture of Investment.” Victorian Studies 45 (1): 17–41.

———. 2008. Genres of the Credit Economy, Mediating Value in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Britain. University of Chicago Press.

Saussure, Ferdinand de. 2011. Course in General Linguistics. Edited by Perry Meisel and Haun Saussy. Translated by Wade Baskin. New York: Columbia University Press.

Taylor, James. 2014. “Financial Crises and the Birth of the Financial Press, 1825-1880.” In The Media and Financial Crises, 203–14. Routledge.

Weir, David. 1995. Decadence and the Making of Modernism. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

White, Nicholas. 2009. “Introduction.” In Against Nature, by J.-K. Huysmans, translated by Margaret Mauldon, vii–xxvi. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Wilde, Oscar. 2006. The Picture of Dorian Gray. Edited by Joseph Bristow. New ed. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ziegler, Robert. 2015. “Huysmans’s Flowers.” Romance Quarterly 62 (1): 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/08831157.2015.970115.

This article is based on parts of my doctoral dissertation. (Gammelgaard 2020)

[1] White, “Introduction,” xx; in Wilde’s Dorian Gray, the book that so influences Dorian, and which is loosely based on À rebours, is described precisely as a “novel without a plot” (Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray, 106).