By John Champagne

First of all, I believe that we should argue for a withdrawal from Lebanon. Then it is just as urgent to stop further construction of settlements in the occupied territories. After that, as I was saying, I would cautiously but firmly move on a withdrawal from the West Bank and Gaza.

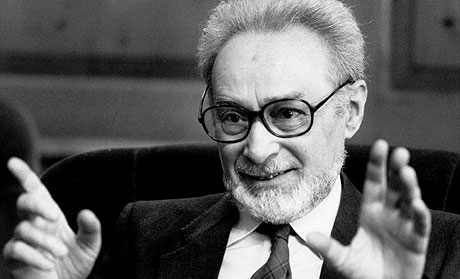

Primo Levi, “If This is a State,” 1984

Introduction

The monthly magazine of the Comunità Ebraica di Roma (Jewish Congregation of Rome), Shalom, publicizes events of local interest; the June 2013 issue thus included “Primo Levi among us,” announcing the exhibition “Survivor: Primo Levi in the portraits of Larry Rivers” (De Canino 2013, 41). Housed in the Museo Ebraico di Roma, in the room titled “From Emancipation to Today,” the exhibition ran from May 9 to October 15, 2013. It was organized around three multimedia works: Survivor (cm. 186 x 152.5 x 15), Periodic Table (named after one of Levi’s most famous collections of personal essays; cm. 186 h x 146 x 15), and Witness (cm. 191 H X 162.5 X 15), each a half-length portrait of the Turinese writer (Melasecchi 2013).1 Previously housed in a conference room at the Turin offices of La Stampa (to which, between 1959 and 1968, Levi contributed regularly), these portraits had never before been available to the public.2

That same issue of Shalom also included the article “Zionism, a Word not Everyone Understands” (Volli 2013). 3 An examination of “an infinite campaign of delegitimation and demonization throughout the world” against Israel, the article identifies recent critiques of that nation-state from both the left and right. Linking such critiques to the “degeneration of anti-Israelian sentiment in terrorism,” the article particularly laments that even the “official press of Italian Judaism” has recently published attacks on Israel. One example cited is an essay by Simon Levis Sullam (2013) that “takes as its starting point the attack on the synagogue of Rome of 1982 for a profound delegitimation of Israel, ‘of its leadership and its disastrous politics’” (Volli 2013; the words in quotation marks are Sullam’s). Interestingly, the Shalom writer has left off, deliberately or otherwise, some of Sullam’s words, as the quotation actually ends with “of the last few years.”

The co-locating, in Shalom, of these two articles adventitiously summons up the ongoing struggle among those affiliated with Italian Jewry to determine the meaning of Primo Levi.4 On the one hand, certain employments of Levi seek to restrict his meaning largely to “Italian Jewish writer” and “Shoah survivor”; on the other, there are efforts to make of the writer an “empty signifier” whose performative function is to condense “a diversity of issues into a relatively stable political project” (Dean 2010, 43-44) and thus “bring into existence political agendas that only tenuously existed before” (44).5 These diverse issues could potentially include not only Levi’s pacifism and critique of anti-Semitism but also a critique of the Israeli occupation and even a critique of humanism (Ross 2010). Perhaps it is apt that Levi once described himself as a centaur – an identity summarized by Marco Belpoliti as embodying not only “the presence of opposites, but also the union of man and beast, of impulse and ratiocination, an unstable union destined to break down. The man-horse is an emblem of the radical internal opposition that every survivor lived through”(2001, xx).

This semiotic struggle to signify Levi has a long history (Cheyette 2007), one that reached a kind of denouement in 1982 and its traumatic events, including the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, the massacres at Sabra and Shatila, and the bombing of Rome’s Tempio Maggiore or Great Synagogue (Marzano and Schwarz 2013; Molinari 1995). Levi’s death in 1987 has attenuated this struggle, for it marked a point wherein what the author said or did not say about Israel, as well as his relationship to his Italian Jewish identity, became a matter not only of scholarship and speculation but sometimes heated polemic. (While the circumstances of Levi’s death are ambiguous, [see Gambetta 1999], a comment on a New Yorker blog in 2013 posted that both Levi’s critique of Israel and his suicide were the product of “his pitiable depressive mental illness”; Eeman 2013.)6

In Politics out of History, Wendy O. Brown (2001) explores some of the “new political and epistemological possibilities” emerging from the ruins of modernity (2001, 5). Working through post-structuralism’s critique of metaphysics, metanarratives, and foundationalism, Brown seeks “to craft a fruitful form of historical-political consciousness” (16), one that “does not resort to discredited narratives of systematicity, periodicity, laws of development, or a bounded, coherent past and present” (143). Brown’s project is in sympathy with a number of other interventions in the wake of the critique of foundationalism, from what is called the aesthetic turn in political theory, to the queer unhistoricism debates in Renaissance studies, to post-colonial historiography as pursued by the Subaltern Studies group.7 All of these interventions hope to conjure a method of historical thinking that avoids a crude historicism. All circle around a series of relationships perhaps most characteristically articulated by Walter Benjamin: between aesthetics and politics, the past and the present, historicism and historicity (1968, 2014).

Reading both Brown and Jacques Derrida, queer Renaissance scholar Carla Freccero uses the tropes of haunting and spectrality to describe an affective relationship to the past and the obligations it brings. “Thinking historicity through haunting thus combines both the seeming objectivity of events and the subjectivity of their affective afterlife,” Freccero suggests (2006, 76). Following Derrida, she employs the term “spectrality” to refer to “the way the past or the future presses upon us with a kind of insistence or demand, a demand to which we must somehow respond” (70). Freccero glosses Derrida’s term as an attempt “to describe a mode of historical attentiveness that the living might have to what is not present but somehow appears as a figure or a voice” (69-70). Clearly, we – those of us with an investment in Italian Jewry – are haunted by the figure of Levi. Rivers’s portraits, their recent exhibition by the Museo Ebraico di Roma, the photographs, poems, and objects included in the exhibition, all constitute a form of spectrality; “something ghostly is being conjured to address a way of calling and being called to historical and ethical accountability” (69).

In what follows, I read Larry Rivers’s portraits of Levi against the backdrop of some of the discursive contexts in which they were – and are – embedded and exhibited. For the Rivers exhibition exposes the contradictory meanings assigned to Levi. This is not deliberate on the museum’s part; rather, it is the result of a series of complex circumstances, including the history of the museum, its relationship to the Comunità, its contradictory museological agendas, and the history of Italian Jewry and Italian Jewish identities. An analysis of Rivers’s portraits in the context of the exhibition illustrates some of the competing contemporary meanings of Primo Levi.

For, as the very title of the exhibit (“Primo Levi Among Us”) reveals, “Primo Levi” has come to signify this question: “What, today, is an Italian Jew?” It is a question so fractious that the single, sustained scholarly attempt in Italian to answer it – Shaul Bassi’s booklength study, Essere qualcun altro (To be someone else) – has gone virtually unremarked by the Italian Jewish press. Bassi writes, “The majority of Italian Jews are for all practical purposes reformed in their mentality and religious practice, but are viscerally hostile to institutionalizing this condition,” sentimentalizing religious orthodoxy but unwilling or uninterested in fully observing halakhà (2011, 252-3). The historical, economic, and political conditions that have made this possible are outlined in Bassi’s book and will only be alluded to here, but, according to one Italian Jewish journalist writing not in Italian but rather English, “In Italy, a Traditional Jewish Lifestyle is Disappearing” (Momigliano 2013).

I argue that “Primo Levi” has become a metonymy for that lifestyle, with both Orthodox and reform-minded Italian Jews (which, as Bassi suggests, might in some cases be one and the same) claiming to be its representatives and feeling equally embattled. Both Orthodox and reform-oriented Jews recognize that the community risks, in Momigliano’s term, disappearing. The Orthodox response, however, is to shore up the boundaries of Italian Jewish identity and in the process make them less permeable – a condition that both Bassi and Momigliano argue is anathema to the history of Italian Judaism. As the subtitle of Bassi’s book suggests, reform-oriented Jews propose a postmodern, postcolonial Judaism that would deconstruct the categories by which Judaism historically has been defined, by both its “inside” and “outside,” philo- and anti-semitism. (Bassi’s position is informed by what is called in English “New Jewish Cultural Studies”; see Bassi 2011, 51-73. On the New Jewish Cultural Studies, see, for example, Cheyette and Marcus 1998; 2002; Boyarin and Boyarin 1997; Eilberg-Schwartz 1992; Gilman 2003; Gruber 2002; Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998.)

As for my formal analysis of the portraits, I see it as a necessary step that brings together aesthetics and politics – the latter conceived here not as “mere policing” but rather as “an event of dissensus” (Shapiro 2013, 140; on this definition of politics, see also Rancière 1999). Attentive to the sensuous specificity of the art work and the way that the art object potentially binds together affects and thoughts so as to propose alternative modes of being, my analysis seeks to foster a critical attitude that “presents a challenge to identity politics in general” and encourage “self-reflection rather than capitulation to the already-institutionalized identity spaces available within prevailing power arrangements – even those on which some challenging social movements are predicated” (shapiro 2013, 8). The formal inventiveness of Rivers’s portraits is in keeping with Levi’s own attempts to express the Shoah, a trauma that defied expression through language (2005, 23), and Rivers’s portraits are themselves an effort to re-figure Levi. In short, for both Rivers and perhaps even Levi himself, “Primo Levi” functions as what Deleuze and Guattari (1994, 177) have called an “aesthetic figure”: “sensations, percepts and affects, landscapes and faces, visions and becoming” – terms that, uncannily, seem to refer specifically to Rivers’s portraits.

My hope is that, simultaneously, my formal analysis of the portraits is an answer to a prescient question for anyone writing about art who seeks to circumvent both a “necrological model” of historiography (Freccero 2006, 70) that would “entomb within writing the lost other of the past” and a related model, historiography as “outright mastery or appropriation” (71):

Is it possible to escape the descriptive illusion in any way other than by denouncing the representationalist hypothesis from which it proceeds, while retaining the rights to an analysis that’s not about painting but rather proceeds with it, but that doesn’t necessitate our allowing ourselves to be spoken by it, like that “experiment with the past” which, according to Walter Benjamin, is history? (Damisch 1994, 263)8

By “the representationalist hypothesis,” Damisch is referring to “the view that representation is the primary function of both language and art” (238). This hypothesis emphasizes the “constitutive transparency” of the sign and “the impossibility of its reflecting on itself in the process of representation” (269). In other words, the representationalist hypothesis is underwritten by a realist epistemology that, as my formal analysis of the portraits will demonstrate, Rivers rejects.

Given its explicit critique of identity politics, my reading thus challenges or at least re-contextualizes some of the ways in which those responsible for the Levi exhibit deploy his figure. Here, for example, is the Museo Ebraico’s sense of what is at stake in the meaning of Levi as evidenced in the words of its current director, Alessandra Di Castro. Note in particular the emphasis on identity:

Survivor. Primo Levi in the portraits Larry Rivers” is the first interdisciplinary show that sets its sights on the contemporary: the struggle is to render the Museo Ebraico di Roma “narrator” of our identity today, both as Jews and Italians. Primo Levi is the emblem, the cornerstone of this new discourse. Across the three portraits, Rivers recounts Levi in all his aspects: the writer, the scientist, the man who was subject to the racial laws and deportation, and the testimony of his experience in the extermination camps.

“In memoria,” 2013.

How does the Comunità’s museum take on the challenge of narrating, via the figure of Levi, an identity (and accompanying politics) that is both Italian and Jewish? Of what does this “new discourse” consist, and how does it interact with traces of previous readings of Levi, at least one of which the museum itself highlights?

For “Survivor: Primo Levi” shared space with several items from its “Emancipation” room left in situ, including a wall panel describing the negative response of (what in the museum text are) unnamed Italian Jewish intellectuals to Israel’s invasion of Lebanon and the events of Sabra and Shatila.9 That is, within meters of a narrative of what the museum calls (arguably, misleadingly) “the first, painful division of the community over the subject of Israel” were three large portraits of the man who embodied that division (Di Castro 2010, 61). As Marcella Simoni and Arturo Marzano (2010, 33) have argued, “In terms of the mobilization of intellectuals, the most definitive” condemnation of the government of then Prime Minister Menachem Begin’s invasion, euphemistically titled “Peace in Galilee,” came from Levi, who accused Begin of “exploiting the Shoah with the goal of a national mobilization in Israel”(Simoni and Marzano’s words). Yet neither the museum wall text nor the exhibition mentioned this coincidence.

Of course, this was not simply a coincidence in that the room chosen for the Levi exhibition is one that normally houses material from the 1900s, including the Shoah. In an effort to create space for the show, some items were relocated temporarily to other rooms, while others were left in place. As a result of the way the museum imagines Roman Jewry from antiquity up until today, the 1900 room has deliberately constructed relationships between Emancipation, Italian Zionism, Italian Jewish Resistance to Fascism, the Shoah in Italy, the “birth” of the state of Israel, and the events that post-date the 1967 war, including the invasion of Lebanon, Italian response to that invasion, and, on October 9 of that year, the attack on the Tempio Maggiore by members of the Abu Nidal terrorist organization that resulted in the death of two-year-old Stefano Gay Taché and the wounding of thirty-seven others (Champagne and Clasby, forthcoming).10 Via the recent exhibition, Levi has been (re)inserted into this context.11

The museum began as a temporary space for the Community’s liturgical objects, many dating as far back as the Counter-Reformation; expanded first into a museum directed primarily toward Jews visiting Rome from North America; and then adopted, in 2005, a program of renovation and reorganization from a chronological to a thematic itinerary.(See Di Castro 2010,13-18 for a history of the museum).12 This reorganization was predicated on a nineteenth-century museum aesthetic of pedagogy (Crane 1997) seeking to educate an audience of Jews and non-Jews, Italians and non-Italians, alike.13 So, for example, while the museum’s explanation of religious Judaism is Orthodox, and thus includes unequivocal statements such as that Jewish law requires that men must cover their heads “at all times, and not only in the synagogue” ((Di Castro 2010, 103), its commitment to the reality of Italian Jewish historical experience necessarily exposes other versions of Italian Judaism. Caught between at least three competing agendas – the preservation of the Community’s history and artifacts, the education of non-Jews in the religious practices of Orthodox Judaism, and a specifically twenty-first-century museological agenda of inviting commentary and controversy, to which, as Alessandra Di Castro’s remarks suggest, the Levi exhibition in part responds – the museum is necessarily marked by contradictions that constitute its very conditions of possibility.14 This contemporary museological agenda is itself a response to Benjamin’s work and the critique of the museum that followed in its wake. (See, for example, Crimp 1999).

Pre-Text: Primo Levi, Italian Judaism, and Israel

There has been a Jewish presence in Italy since antiquity, and, unlike many other regions in Europe, Italy never expelled its Jews (Mendel, 2005).15 Italy was also, however, responsible for the invention of the ghetto, the first of which dates from sixteenth-century Venice. In 1555, as part of the Catholic response to the Protestant Reformation, Pope Paul the IV issued Cum nimis absurdum, the Papal bull that revoked Jewish rights in the Papal states, forced Jews to live in ghettos and wear visible signs so that “they may be recognized everywhere,” and limited Jews in terms of their occupations.16

It is extremely difficult to generalize about the long and rich history of Italian Jewry prior to Italian Unification, given the very different circumstances Jews faced throughout the territory of present day Italy. For example, while both Venetian and Roman Jews were confined to ghettos, the former, owing to a variety of factors including the Republic’s desire to maintain autonomy from the papacy and its recognition of the economic and trade benefits of a Jewish presence, flourished despite their oppression, developing a rich artistic and intellectual culture whose influence spread far beyond the ghetto walls; Roman Jews, under the thumb of the papacy, instead lived in poverty.17 At various times in European history, Jews fled from other lands to Italy; as a result of the Spanish expulsion of 1492, for example, many Italian Jewish communities saw the arrival of new members, who, because of the ghetto laws, were by the late sixteenth century typically required to worship in a single synagogue, despite the varying rituals that had developed as a result of the Diasporas. Like their Venetian co-religionists, Jews in Livorno flourished – under the Medici, who were interested in attracting Sephardic merchants expelled from Spain (Trivellato 2009). The Habsburgs similarly saw the advantage of the Jews of Trieste: “All Jews who could increase the commerce of the free port were welcome” (Dubin 1996, 61)

Italy’s Jews were first emancipated by the Napoleonic conquest, but anti-Jewish laws were reinstated via the Restoration. The Jews of Turin were emancipated in 1848 by Carlo Alberto Savoy, at that time King of Sardinia (which included Piedmont). Italian Jews largely participated in and supported the Risorgimento and the unification of Italy; it was not until Rome was added to a unified Italy that Roman Jews were emancipated, and various congregations in Italy – among them, Rome and Florence – built monumental synagogues in the wake of unification. As one writer suggests, among Jews, the emancipation brought “the explosion of political passion for liberal and socialist ideas” (Molinari 1995,7; on the role Jews played in Italian Unification, see also Molinari 1991).

During this same period, the papacy was resolutely opposed to Italian Unification (Webster 1960, 5-9), and, even after the founding of the state, discouraged Catholic participation in the political, social, and economic life of Italy – a situation that remained until Mussolini signed, on behalf of King Victor Emanuel III, the 1929 Lateran Pacts. As a result of this history, it is misleading to speak chiefly of Jewish Italian “assimilation,” as the national identity of Italian Jews was formed contemporaneously with the process of Italian Unification (Molinari 1991, 26). Italian Jewish identity must be understood historically as “in continual precarious balance between integration and assimilation” (26).

Prior to the 1938 racial laws, some Jews belonged to the Fascist party, while others opposed Fascism. Levi’s natal city of Turin was a center of resistance activity (Nezri-Dufour 2002, 20-21), and many of its intellectuals were members of the underground anti-Fascist organization Giustizia e libertà (Ward 2007, 11). Founded in 1929, the organization had members both within Italy and abroad (Shain 2005, 99). It had a significant Jewish membership, and, in March of 1934, several of its members from Turin were arrested for anti-Fascist activity (Sarfatti 2006, 69-79; Zuccotti 1996, 28-29; Nezri-Dufour 2002, 21-22; Felice 2001, 134-37). Despite the fact that the members of the organization were not Zionists, the incident set off a debate in the Fascist press concerning whether or not Italian Jews’ loyalty was divided between Israel and the country of their citizenship.

The question of Levi’s relationship to his Jewishness is a complex one. Levi wrote that it was only as an effect of the 1938 anti-Jewish laws and his deportation to Auschwitz that he came to see himself as Jewish (Levi 1984b, 376, Parussa 2005).18 In one of his memoirs he describes being “amazed” that the end of the war did not bring an end to anti-Semitism (1987, 41).19 Levi’s family was not religious but did celebrate certain holidays like Rosh Hashanah, Passover, and Purim (Levi 1984, 377). His parents had been married in the synagogue (Thomson 2002, 16); Levi was circumcised according to Jewish custom (Thomson 2002, 18) and had a Bar Mitzvah and the necessary religious training preceding that ceremony.20 While Levi was far enough along in his own studies that anti-Jewish laws did not interrupt his university education, his younger sister was, like all Jewish children, expelled from her state school in 1938 (83-84).

On the complexity of Levi’s identity, Nancy Harrowitz has argued that “Levi’s family and Levi himself had a distinct Jewish identity, which was in part religious, and could not straightforwardly be labeled ‘assimilated’” (Harrowitz 2007,18). Indeed, Levi’s family was typical of many other Italian Jewish families of the time in that they embraced “a so-called ‘secular’ or ‘cultural’ Judaism” (2007, 17; on such families and their identities as Jews, including Levi’s, see also Nezri-Dufour 2002, 13-19). Paola Valabrega (1997, 264) describes Levi’s as “a typical Jewish family, depository of an atavistic code of values.” She also emphasizes the way Levi’s Jewish identity was deeply tied to his family history and memories and identifies this fondness for the family (and the symbol of the family as haven) as a typically Jewish trope (268). Another important aspect of Levi’s Jewish identity was an association of Judaism with a passion for learning, subtle debate, and “the world of books” (Levi, cited in Nezri-Dufour 2002, 15).

According to Levi and many other “cultural” Jews, this lack of orthodox religiosity was due to the fact that Jewish emancipation was the fruit of the secular character of the Italian Risorgimento (Levi 1984b, 76; Nezri-Dufour 2002, 17). In a 1984 interview, Levi stated, “I am in favor of the integration of Jews in Italy, but not of their assimilation, their disappearance, the dissolution of their culture. Right here in Turin, there is an example of a Jewish community that is fully integrated into the life and culture of the city, but not assimilated”(1984a).

As we will see, however, Levi’s understanding of Italian Judaism, at least as summarized by Harrowitz, is not in keeping with the Comunità Ebraica di Roma’s Orthodoxy. As Harrowitz writes, Levi’s family was “perhaps closer to what contemporary British or American Jews would call, respectively, Reform or Conservative Judaism” (Harrowitz 2007, 17). Levi also resisted being categorized, in the United States in particular, as a “Jewish writer” (Cheyette 2007, 67). He is reputed to have said once, “I don’t like labels. Germans do” (Angier 200 2, 645). On the other hand, according to one critic, “Levi rarely missed an opportunity to identify himself as Jewish throughout his writings” (Sungolowsky 2005, 75).

This tension between Orthodoxy and Levi’s Judaism is perhaps most rigorously emblematized in the fact that the Jewish Museum of Rome both claims and does not claim Levi as one of the Comunità’s own. In mounting the Rivers’s exhibit and framing that exhibit via the above-cited comments by the Museum’s director, the Museum itself clearly construes Levi as not only Jewish but as a model of contemporary Italian Jewish identity.21 Yet as I have mentioned, he is not named in the museum’s in situ wall commentary concerning the Comunità’s response to both the invasion of Lebanon and the events of Sabra and Shatila.

As for Zionism, at least one biographer has argued that Levi was ambivalent, suggesting that, prior to the Shoah, while he “admired the ideals of left-wing Zionism,” he was not a Zionist himself (Angier 2002, 628). This same biography suggests this changed after the war, as Levi felt the Jews needed a home where they might be safe from persecution.22 “But immediately he had had doubts and reservations: about the Palestinian expulsions, about the nascent militarism of this homeland born of war” (638). Levi visited Israel for the first and only time in 1968 and was disturbed by its militarism and the fact that securing a home for those Jews who had been dispersed by the Shoah occurred without regard to the Arabs living in the region (Thomson 200 2, 340-42). By the 1980s, Levi was “one of the promoters of an appeal for withdrawal of the troops and for a peace process to guarantee a homeland to those who did not have one” (Belpoliti 2001, xxv). Late in his career, he gave an interview in which he suggested that in the “center of gravity” of Jewish life was in the Diaspora and that he valued the “dispersed, polycentric” quality of Jewish culture (1984a 290-91).

Since Emancipation, some Italian Jews were at best ambivalent about Zionism.23 A phenomenon linked to Tarquini’s analysis was raised often in post-emancipation defenses of Zionism, particularly when Mussolini made a point of questioning Italian Jews’ commitment to their nation. 24 As Rabbi Sonnino’s comments suggest, Italians had a long history of sending monetary contributions to poor Jews living in the Middle East. Michele Sarfatti refers to this as “philanthropic Zionism,” which also sought to free Jews from anti-Semitic persecution (Sarfatti 2006, 11-12). For at least some Italian Jews, however, this did not translate into support for a nascent Jewish state. An Italian historian of science has suggested that Italian Jewish support for Zionism “was of only marginal significance until the pressure of the [Fascist] regime convinced the Jews to turn in that direction” (Israel 2004).

On the other hand, it has also been suggested that, by the beginning of the twentieth century, Italian rabbis “supported Zionism almost without exception” (Laquer 2003, 161). Bringing these two comments together, a noted Italian Jewish scholar argues that “Italian Zionism before the racial laws was essentially the result of the actions of a group of rabbis” (Segre 2000, 190). In any case, both prior to and following the war, Italian Jews did not immigrate in significant numbers to Israel.

Historians have argued, however, that, following the war, changes in the leadership of the Comunità, on both the national and local levels – specifically, the active part played in Jewish intellectual and cultural life by surviving anti-fascist, pro-Zionist Italian Jews – led to “a general acceptance of Zionism as a key reference point in Italian-Jewish identity”(Schwarz 2009, 370). However, “new instability arose when (beginning from 1956 but growing more obvious since 1967) a clearer anti-Zionist position emerged in these [Communist and Socialist Italian political] parties, unsettling the position of many individual Jews, as well as many Jewish youth organisations” (Schwarz 2009, 371). Furthermore, “in the post-war period, anti-Zionist feelings were still present within Italian Judaism, but they remained for the most part in the private sphere.” (Schwarz 2011, 51).

In order to understand Levi’s later response to Israeli military policies, we might place that response in the larger context of Italian politics and Italy’s relationship to Israel. On the occasion of the Six Day War, the majority of Italian political forces, the Italian press, and public opinion all sided with Israel, filtering the conflict “through the prism of the common struggle against fascism and the memory of the racial persecution” (Marzano and Schwarz 2013, 48; on this period, see also Molinari 1995, 28-45; Di Figlia 2012, 77). That war also exposed, however, divisions within the Italian government, but a compromise was arrived at thanks to Prime Minister Aldo Moro, who “reaffirmed the right of every State to political independence, territorial integrity, and protection from threats and the use of force, but also considered it necessary to confront the question of the Israeli retreat from the occupied territories in view of a shared stable territorial arrangement of the various parties” (Marzano and Schwarz 2013, 51). In 1969, Levi himself joined a protest against Israeli military policy, a protest headed by a group of “left-wing Jewish intellectuals in Turin” (Angier 2002, 628). Along with thirty others, he signed a document arguing that Palestinian guerrilla activity was “not terrorism, but ‘resistance’” (Molinari 1995, 56). and defining Israel’s actions as destined to augment “extremist and expansionist positions” within Israeli society (57).

By the time of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the political climate began to change; while the majority of Italian public opinion still favored Israel, there were increasing calls, by the leftist parties and press in particular, for the restitution of the territories occupied in 1967 and for the rights of the Palestinians to a “national and autonomous entity” (Achilli 1989, 187; Di Figlia 2012, 79-80). In 1975, in Levi’s home of Turin, a new journal, Ha-Keilà (The Community), was launched by a group of “progressive” (their own term) leftist Jews who supported the birth of an independent Palestinian states alongside Israel (Molinari 1995, 87; Di Figlia 2012, 104-09). By the end of the 1970s, in Italy and elsewhere, the Palestinians had become a symbol of a global, revolutionary struggle against imperialism (Marzano and Schwarz 2013, 73).

While Levi never equated the Palestinians with the Jewish victims of Fascist violence, according to one writer, he “wished to situate the Holocaust in the context of global injustice” (Cheyette 2007, 69). This situating included a critique of France in Algeria and the United States in Vietnam. US support for Israel contributed to the perception of the Palestinians as engaged in a struggle for national liberation. As early as 1967, some members of the Italian left were in fact comparing the Israelis to the French and the Americans (Molinari 1995, 33). In Italy, anti-Imperialist struggles took on the particular symbolic contours of the memory of the Resistance and antifascism, which in turn led in some quarters to an equating of the policies of the Israeli government with Nazism (Marzano and Schwarz 2013, 29).25 By 1981, the situation was further complicated by a rise in right-wing anti-Semitism in Italy as well as anti-Semitic violence in Italy and abroad (100-104).

By the time of the 1982 war in Lebanon, Italian public opinion was generally oriented toward a condemnation of Israel (Marzano and Schwarz 2013, 56). Levi has been described as “a key figure for understanding the spirit of the time” and someone who throughout the war in Lebanon received a great deal of media attention (157). Some of this attention was due to the recent release of his novel Se non ora, qunado? Harrowitz characterizes these years as ones in which Levi “tried to make the clear the distinctions between Jews and Zionists” (Harrowitz 2007, 20).

As a result of the 1982 war in Lebanon, termed “Operation Peace in Galilee” by the Israelis, many Jews living in the Diaspora questioned the relationship between their communities and the state of Israel (Sullam 2013). Opinion was divided on whether Israeli actions constituted a defensive or offensive war. Several Italian Jewish intellectuals, including Primo Levi, signed “Perché Israele si ritiri,” or “Why Israel must withdraw,” a condemnation, published June 16, 1982, of the invasion.26 This document called for opposition to Begin and what the document characterized as the threat he represented, both to a democratic Israel and to the prospect of its peaceful coexistence with the Palestinian people (Scarpa and Soave 2012). It argued that “to combat Begin means to combat the germs of a new anti-Semitism” and called for the recognition of a “Palestinian Resistance” (cited in Molinari 1995, 106).

On June 24, after calling Israel a country that “feels like my second home,” Levi stated his fear that the war in Lebanon, “frightfully costly in terms of blood, inflicts on Judaism a degradation that can be curable only with difficulty and a tarnished image” (1997, 1172). Three days later, in an interview in La Repubblica, Levi (1982b), while resisting the positing of an analogy between Hitler’s “Final Solution” and “the quite violent and quite terrible things the Israelis are doing today,” nevertheless argued, “a recent Palestinian diaspora exists that has something in common with the diaspora of two million years ago” (cited in Scarpa and Soave, 2012).27

On July 6, 1982, in part in response to Levi’s condemnation, Jewish journalist Rosellina Balbi published, also in La Repubblica, “Davide, discolpati!”or “David, defend yourself!” an article justifying Israel’s actions as defensive and arguing that any critique of the state of Israel has punctually provoked across Europe “tremors of anti-Semitism” (quoted in Baroz, 2013). “Why Israel Must Withdraw” was also critiqued by other Italian Jews, including rabbi Scialom Bahbout, described as “one of the most charismatic of Rome” (Molinari 1995, 106), and head rabbi Elio Toaff.

The issue of the war in Lebanon was brought to a head with the revelation of the September 16-18 massacre of several thousand Palestinian men, women, and children at the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila. The massacre was perpetrated by Lebanese Christian Phalangists whom the Israeli army had invited into the camps (Mieli 2012; Shahid 2002, 38).28 and to whom they had provided logistical and operational support (Shahid 2002, 42).Following the massacre, in an interview in La Repubblica, Levi called for the resignation of Begin (1982a, 295-303). Levi stated that “for Begin, ‘fascist” is a definition I accept” (1982a, 298).”29 About the failure of the Israeli army to intervene in the atrocities, Levi said, “The massacre in these camps reminds me of what the Russians at Warsaw did in August of 1945; they stood by on Vistula while the Nazis exterminated Polish partisans. Certainly like all historical analogies, even mine is inexact. But Israel, like the Soviets then, could have intervened” (1982, 301). The next day, he and other Italian Jews demonstrated outside the Israeli embassy (Cicioni 1995, 129). This demonstration revealed “the rift between the two spirits” of the Italian Comunità, for “the traditional and popular base” of Roman Judaism was absent from the demonstration (Molinari 1995, 107). In 1983, an International Commission on the deaths at Sabra and Shatila concluded that Israel had violated international law, “systematically refused to settle its disputes peacefully” (MacBride et al 1983, 128) and “played a facilitative role in the actual killings” (130).

The publication in 2012 of Matteo Di Figlia’s excellent Israele e la Sinistra, exploring the period from 1945 to today, reinvigorated the debates around Levi’s politics, prompting commentary from all sides of the political spectrum.30 Figlia’s book takes as its project a rereading of the participation of Jews and the Italian Left in the debates on Israel, seeking to complicate the treating of both Jews and the Left as monolithic and tracing out the specific trajectory of the thinking of individual Italian Jewish intellectuals. For example, he offers a more nuanced argument than the claim that those on the Italian left who pursued a pro-Palestinian line were simply following the lead of Cold War Moscow.

Until the end of his life, Levi continued to speak out against Israeli military policy when it went beyond what he perceived as defensive. Following his death, and in a kind of summa of Levi’s sensibility, Stefano Levi Della Torre (1997) – a painter, scholar, professor of architecture, and cousin of Levi’s – wrote that Primo was considered by some “an irritating character”:

the more embarrassing a critic, the more morally and intellectually authoritative, and representative of the most terrible of Jewish experiences. But for those Jews who envisaged “Hahavat Israel,” love for Israel, love for justice as well, and for that tolerance that is founded on memory (“Do not oppress a stranger, because you yourselves already know how it feels to be a stranger, because you were strangers in Egypt”, Exodus 23:9), Primo Levi was instead a teacher [maestro], despite that, as often is the case with teachers, he had neither the intention nor the presumption to be one. (261-262)

The exhibition

In 1987, shortly after Levi’s death, Gianni Agnelli commissioned Larry Rivers to create a portrait that would commemorate both the writer and at the same time the Jews exterminated by the Nazis. Agnelli – Fiat heir and tabloid and political figure – had studied in the same Turin liceo as Levi.31 [31] Rivers’s portraits thus constitute a kind of historiography as well as a premonition of what will be the aesthetic turn in political science. Yet it is one that, via its formal properties, is arguably not a history that would seek “to identify, and thus stabilize, the meaning of an event or a person” (Freccero 2006, 74).

Reflecting Rivers’s aesthetic – a mingling of influences from abstract expressionism, cubist collage, and pop art – the portraits are assemblages: photographic images of Levi silk-screened, à la Andy Warhol, on canvas that has then been mounted on molded polyurethane foam, attached to a background and “supplemented” with additional images: painted and drawn directly on the canvas or modeled in polyurethane, abstract and representational. The effect is that of a reassembled three-dimensional puzzle hung vertically, Levi having been “pieced together” by Rivers from the traces left behind after his death.32

Rivers’s developed some of these techniques, and their use in the depiction of Holocaust images, in his 1981 Four Seasons at Birkenau. A photograph of Jewish civilian prisoners in a forest is reproduced on foam core. Rivers then alters the image by drawing “over” it with colored pencils, cutting out various figures (people and trees) and pasting them on top of another piece of form core onto which the artist has drawn additional figures and trees. As in the case of the Levi portraits, an image has been both appropriated by the artist and altered.

Being images of images, the portraits, like Four Seasons, seek to circumvent what Walter Benjamin so famously called the art work’s aura, as “the presence of the original is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity” (2014). Rivers’s deconstruction of authenticity is of a piece with the “spectrality” of the portraits, suggesting that “we inherit not ‘what really happened’ to the dead but what lives on from that happening, what is conjured from it, how past generations and events occupy the force fields of the present, how they claim us, and how they haunt, plague, and inspirit our imaginations and visions for the future” (Brown 2001, 150). It suggests the way that art in the age of mechanical reproduction might contain certain conditions of possibility whereby we might “seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger” – whether that moment be the one in which the portraits were commissioned or the one we inhabit today (Benjamin 1968, 255).

Four Season at Birkenau has a particularly complex relationship to linear perspective, as Rivers has “disassembled” a photograph (which relies for its illusion of three dimensions on the technology of the camera lens) and then “reassembled” it in a way that adopts from other representational systems “alternative” methods for creating the illusion of depth, such as layering images on top of one another and using the lower half of the canvas space to represent foreground and the upper half to represent distance. Employed in the painting of religious icons, for example, these precursors to linear perspective are rescued from the trash dump of history and cited by Rivers. Of course, Renaissance painting made use of a whole series of techniques, including the layering of images on top of one another, to create the illusion of depth. When juxtaposed with the rendering of perspective via a photograph, however, the “inferiority” of these other techniques (in terms of the degree to which they convey the illusion of depth) is foregrounded.

These “non-Renaissance” means of imagining canvas space also refer in complex ways to forms of illustration like comics and advertising. On the one hand, comics often also reject perspective for other means of creating depth, and the Levi portraits in fact have a cartoon like quality that emphasizes drawing (and draftsmanship) over painting. On the other, Rivers’s use of photographs suggests advertising’s exploitation of cheap methods of color photography to create the illusion of an image that the consumer might possess. Rivers’s techniques of disassembly and over-drawing work against this particular aspect of advertising, perhaps constituting a version of Benjamin’s envisioned dialectical response to the invention of cheap forms of mechanical reproduction, the withering of the art work’s aura, and “the phony spell of a commodity” (1936).

In contradistinction to Warhol, rather than musing primarily on the status of publicity, public relations, advertising, and news in commodity culture, Rivers focuses on historical and cultural icons and then alters them via drawing, painting, and sculpting.33 Rivers’s appropriations are characterized by a more obvious intervention of the artist’s hand than Warhol’s, in the form of both painting and drawing over the silk-screened photographs, in this case indicating a “working over” rather than a monumentalizing (in the Nietzschian sense) or even an advertising of a fixed image of Levi. Rivers’s works are thus a visual analogy for the post-war debates in cultural theory concerning the role of human agency in what is increasingly experienced as our collective subjection and subjugation to cultural, economic, and historical forces beyond the control of the individual. Additionally, the “playfulness” of Rivers’s pop aesthetic mitigates what Cheyette terms a tendency to “appropriate” Levi – as symbol of Christian redemption via suffering, for example (2007, 69). The title of one of the portraits, “Witness,” is a word Levi used to refer to himself, opposing it to both victim and one who seeks revenge (cited in Cheyette 2007, 70).

Rivers’s re-imaging of canvas space and combining of media result in what Leo Steinberg so famously categorized as works that “no longer simulate vertical fields, but opaque flatbed horizontals” (Steinberg 1972, 44). The Levi portraits make “symbolic allusion to hard surfaces such as tabletops, studio floors, charts, bulletin boards – any receptor surface on which objects are scattered, on which data is entered, on which information may be received, printed, impressed – whether coherently or in confusion” (44). For while the portraits hang so that they are oriented to the standing human being, the works do not depend on this head- to-toe orientation any more than newspapers – or the photographs on which the portraits were based – do. They exemplify Steinberg’s “flatbed picture plane,” referring not to “the analogue of visual experience of nature but of operational processes” (1972, 84). Such an aesthetic suggests that the meaning of Levi is not transparent or self-evident but must be arrived at via labor – another way in which Rivers’s portraits are not simple appropriations but rather reinventions of Levi.

Like the “work” of survival and mourning, Rivers’ techniques are a working over and through historical trauma. Rivers has taken on aesthetically the problem of representing what in static images is unrepresentable: the temporal and spatial simultaneity of past and present that occurs in the act of remembering, memory’s layering of the past over and under the present; the spatio-temporal discontinuity between the past and present; the almost unfathomable cruelty of the Shoah; Levi’s representation of that cruelty in prose, in Se Questo è un uomo specifically, that refuses to turn away from or even sentimentalize its horrors. That is, refusing the “critical orthodoxy” of the logic that dictates that only a documentary aesthetic is adequate to the representing of the Holocaust, Rivers has attempted to create a plastic equivalent of what it means to be a survivor of a historical trauma (on this orthodoxy, see Cheyette 2007, 68).

Rivers’s layering of images on images “doubles” Levi so that his torso – and face, when shown in profile – appear to cast a shadow, but that shadow is itself constructed of foam core. In Survivor, for example, Levi’s right hand (which touches his chin), his nose, his lips, his shirt pocket and sleeves, and the nose of an internee are all modeled of polyurethane and layered on top of Levi’s “original” image, such that Rivers is building images upon images. Depending on how an exhibition space is lit, these raised areas will themselves cast shadows on the canvas, the irregularity of the layering ensuring that almost any lighting whatsoever will produce shadow somewhere on the portraits. As a survivor, Levi is always somewhere marked by shadow – but also by light.

But not content simply to “add” to the canvas, Rivers also subtracts, cutting out sections. In Periodic Table, the doors of the crematory oven have been layered atop the canvas, as if the ovens had been constructed and then hollowed out to create their depth. Layered over the hollowed-out space are burning objects, and names of some of the elements are written in cursive script on the ovens – emphasizing the canvas’s flatness, as if it were a chalkboard. In Survivor, part of Levi’s forehead has been removed and an internee’s head inserted into it. (For an image of the photograph from which the internee is drawn, see Hunter 1989,52). These techniques foreground the constructedness of the image, re-introducing the artist’s hand into the work not in a gesture of self-expression but as a reminder of the iconicity of Levi and the construction of Levi as icon. Rivers’s work, then, is “figurative without being realist” (Jodidio 1990, 77) as well as a negative intervention in what Benjamin (1968) called “the long-since-counterfeit wealth of creative personality” (232).

Another interesting technique of layering is the use of paint itself to connect the present with the past, sometimes represented on different spatial planes. For example, in Survivor, the past, represented by the stripes of a concentration camp internee’s uniform, “bleed” onto the portrait of Levi layered on top of the canvas. In Periodic Table, four black stripes, like the shadows of prison bars, connect a crematory oven with Levi’s portrait, which is layered on top of the oven. In Witness, Levi’s hair blends into the smoke from a crematorium, both painted in thick impasto.

But this relationship in both portraits between past as background and present as foreground is simultaneously reversed: in Periodic Table, the left side of the crematory oven has been painted over Levi as survivor, but in such a way as to leave the writer visible. That is, the crematory oven is neither behind nor in front of Levi, but both at the same time (and vice versa), as if Levi’s head were partially translucent. Similarly, in Survivor, the internee is behind and on top of Levi at the same time, for while Levi is layered on top of the prisoner’s torso, the stripes from his uniform are painted on Levi’s face, and while Levi’s face is on the plane closest to the spectator, a space has been carved into Levi’s forehead, and the internee’s head inserted into it. Perhaps most startlingly and with much virtuosity, in Witness, a portrait of Levi has been placed onto the canvas-covered foam core surface, but then another picture has been literally “carved” into the writer. In an ironic use of trompe l’oeil, a barbed wire fence and a set of train tracks seem to be receding into Levi’s body. In the foreground are images of children of the Shoah, layered on top of the canvas and painted with varying degrees of abstraction. Levi himself is then placed in a room that resembles a bunker, but one apparently filled with the smoke of the crematory ovens, his hands, themselves on different planes, struggling to grasp the young victims.

In all of these instances, though to varying degrees, Levi has been rendered translucent, his bodily identity and boundaries “interrupted” by memories and reminders of the Shoah. For the photographs from which all of the portraits have been constructed are from his years after having been an internee. The sum of these techniques is a brilliant paradox. In all three cases, the boundaries between Levi and the past have been both erased and reasserted. Present and past interrupt one another, not only temporally but spatially. Levi as survivor is behind, in front of, and traversed by images of the Shoah.

The black lines that in two of the portraits traverse Levi’s face, while literally connecting the contemporary image of Levi to an image of the past, also reference both carbon and ash; as the brochure for the exhibition reminds us, “il carbone ha la stessa valenza della cenere,” “carbon has the same valence as ash.” Carbon is the main element in all organic matter; ash signifies both the horrors of the Shoah ovens and refers to God’s punishment of Adam and Eve in Genesis 3:19. In a related vein, the brochure mentions Rivers’s technique of “cancellation,” wherein the artist drew and then partially erased images. A technique Rivers developed via a series of drawings of Holocaust victims, this erasing is similar to the painting techniques employed by Rivers in the Levi portraits in at least two respects. On the one hand, it is another version of rendering the Holocaust victim “translucent,” there and not there at the same time, for, in the “canceled” drawings, parts of the figures have been erased. On the other, the erasing techniques lighten the hues of the colors and blur the drawings’ lines, creating diffuse patches and swaths of color. The ashy stripes and washes in the Levi portraits are thus painterly versions of cancellation, the washes re-presenting both color and its subtraction, the presence of the artist and his subtraction; “the lifework is preserved in this work and at the same time canceled” (Benjamin 1968, 263).34

Additionally, Rivers’s washes of color and stripes also refer to American abstract expressionism, and in complex, ironic ways. For here and elsewhere, Rivers seems to be exploiting and commenting upon, in a mannerist fashion, the conceit of painting as gesture, as his contemporary Jasper Johns also did (On Rivers’s influence on Johns, see Hunter 1989, 25). On the one hand, the lines, as well as the loose, abstract shapes and washes of color that appear in all three canvases, reassert the flatness of those canvases. Spread across the canvas surfaces, the patches of color obstruct attempts to read the image perspectivally. Countering River’s building up of raised areas as well as those areas where he has resorted to the use of linear perspective – the crematory ovens of Perodic Table, the receding train tracks and barbed wire fence of Witness – the lines and washes of color create an interesting visual tension between the two and three dimensional that adds to the paintings’ deconstruction of a series of binary opposites: not simply flatness/depth but also foreground/background, past/present, inside/outside, present/absent. Complicating this tension even further is Rivers’s use of these washes of color in a more traditional manner – to shade Levi’s face and body. Once again, Rivers combines different representational systems simultaneously.

Rivers’s critically reflexive appropriation of painting as gesture suggests that, in a post-Shoah world – the very world in which the American expressionists “stole the idea of modern art” (Guilbaut 1985) – the conceit of art as a vehicle for either self-expression or transcendence of material reality is obscene. In a related vein, in all three portraits, the abstract patches also read as so much dust – taking us back to the tropes of carbon and erasure. This is particularly true of Periodic Table, where the white painted areas dirtying Levi’s black suit resemble ashes from the crematory ovens. Similarly, in Witness, the smoke and ash from the ovens threatens to overtake the bunker and, as in the previous painting, Levi’s jacket is “stained” by abstract washes of color. The palette of all three canvases call up images of fire (via Levi’s skin tones in particular, but also, in Witness, the wash of color that connects Levi’s body with both the bunker in which he has been placed and the train tracks, barbed wire, and children) and ash.

The Exhibition Context of the Portraits35

In addition to the portraits, other elements of the exhibition included three photographic portraits of Levi; three glass cases; and commentary on the exhibition in the form of wall text (much of it reproduced, though in a different order, in the Italian language exhibition brochure); as well as the words, painted on the wall in Levi’s own hand-writing, of the poem with which Se questo è un uomo opens, “Shemà,” itself the “name of the central prayer in Judaism” (Harrowitz 2007, 28).Read scrupulously, this context is highly contradictory, a site in which competing models of a relation to the past are juxtaposed, sometimes even in the same artifact. For example, the preservation of Levi’s handwriting on the wall serves, in the space of a museum, an auratic function; like expressionist painting, it preserves traces of the dead author’s human presence. But the colored script also calls up the image of so much graffiti. Perhaps not surprisingly, although the exhibit has since closed, Levi’s poem remains on the museum’s walls.

The first glass case contained the manuscript of “La Bambina di Pompeii”, a poem published first in La Stamp, December, 23, 1978, and successively in the collection Ad ora incerta of 1984. Rivers’s drawing technique of “cancellation” and its painterly phantom double have the paradoxical effect of making present an absence, much the way ash is an index of what no longer exists. “La Bambina” is similarly about the presence of absence, for it recounts the traces in the present of murdered children. The plaster cast of one of Pompeii’s victims, the writings of Anne Frank, a Japanese schoolgirl transformed by Hiroshima into “ombra confitta nel muro dalla luce di mille soli,” (shadow driven into the wall by the light of a thousand suns): each is the visible reminder of a child erased from existence. As we will see, these images in turn potentially resonate with the wall text left in situ and its reminder of the children murdered in the Israeli-Palestinian conflicts.

However, the enclosing of the manuscript in a glass case repeats the monumentalizing gesture of the other glass cases. They seek to reinvest the mechanically produced objects they contain with aura by conferring on them a “unique existence” in the space and time of the exhibit. If “the technique of reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the domain of tradition,” the enclosure of that object in a glass case re-endows the object with “cult value” (Benjamin 1936). Thus a first (1947) edition of Se questo, open to the first page of the chapter “Il Viaggio,” occupied the second glass case. The page describes the February 21, 1944 announcement that all Jews currently interned at Fossoli were to be deported: “Per ognuno che fosse mancato all’appello, dieci sarebbero stati fucilati/for each one missing at the roll call, ten will be executed.” The third case contained a leaflet advertising this same novel, on the back of which (and thus unable to be seen) was a print of the manuscript of “Shemà.” The leaflet copy does not mention Levi’s Jewishness, but perhaps this is simply because his name would be recognized as of Jewish origin.

Three oversize black and white photographic portraits hung on one wall of the room. They include a portrait of a smiling young Levi seated on a bench in a garden at the home of his maternal grandparents; an image of the post-Shoah Levi in profile posed in front of a photograph of an internee lying in his bunk, the wideness of the latter’s gaze paradoxically suggesting both life and death simultaneously; a photo of Levi surrounded by students from the Scuola Media Rosselli. The overall effect of these photographs is haunting, as they remind us of Levi’s past (Levi portrayed as an adolescent, at an age where his arms and legs have grown so fast that they seem too long for his body); his survivor present, as depicted in the two portraits from the post-Shoah years; and his future death under ambiguous circumstances. But the photographs themselves are of little value, inexpensive reproductions of casual snapshots.

The Portraits in the Context of the Emancipation Room

In terms of what was left in situ in the room, these included a camp uniform and other objects from the post-emancipation period, including an 1860 Chair of the Prophet Elijah used for circumcisions, sketches and a model from the competition for the building of the Tempio Maggiore, two contemporary art works, and a portrait of Samuele Alatri, Jewish Italian patriot and politician.

On the wall of this room is a text in Italian, English, and Hebrew, labeled “Rome and Israel.” This text narrates the history of Roman Zionism from the turn of the twentieth century to the present. It asserts that “the entire community has always stood side by side with the Jewish state” ((Di Castro 2010, 61), “organizing aid and assistance during all of Israel’s wars” (wall text). But, seemingly contradicting itself, the text then references some of the aforementioned events of 1982. In that year,

When the Israeli army was forced to defend the country’s northern border with Lebanon from Palestinian [sic], a group strongly critical of Israeli policy arose within the Jewish community of Rome. An appeal published in the Rome daily La Repubblica after the widely discussed massacres of Sabra and Shatila, signed by numerous Jewish intellectuals, was the first, painful division of the community over the subject of Israel (61).36

Note how, though unnamed, Jews (like Levi) who protested Israeli military policy are also construed as belonging to the Roman Comunità. According to Ward, Levi was not living in Rome at this time (Ward 2007, 3). Levi is thus, however inadvertently, construed as simultaneously belonging and not belonging to the Comunità. The museum is not alone in this regard, as at least one other historian refers to these events as having revealed cleavages within “le Comunità ebraiche” (Molinari 1995, 106).

As the previous discussion of Italian Zionism suggests, these comments are perhaps a bit misleading, in part the result of the ambiguity around just what constitutes the Jewish “community” versus those inscribed in the register of the Comunità. “Rome and Israel” specifically cites Dante Lattes as one of the figures responsible for the “spread” to Rome of what it terms political Zionism ((Di Castro 2010, 58). Lattes’ “Ed il libro?” however, had expressed concerns over the way some aspects of post-emancipation Italian national identity seemed to undercut Jewish cultural and religious identity – a point the guidebook does not mention.

Although, in a discussion of Enzo Sereni, the guidebook mentions the “pioneering, Socialist wing of Zionism,” the birth of the state of Israel is constructed as a narrative that leads directly from Socialist to Political Zionism; the comments that the Comunità has always stood by Israel are prefaced by a comment that it was led in this direction first by Rabbi David Prato, “an ardent Zionist” ((Di Castro 2010, 61). Sereni occupies a crucial role in the museum’s constructing of the link between Zionism and Roman Jewish anti-fascism, as when the museum text describes him and his wife as “two people destined to make an enormous contribution to the history of the future state of Israel, Enzo to the ultimate sacrifice, in 1944, parachuting beyond German lines in his attempt to save the Jews of Rome from the Nazis.”

Fascism was an ultra-nationalist ethos whose adherents in Italy forced Jews to side with the Italian state by denying Zionism and a universal Jewish identity. After the Holocaust, the effect of this refusal of temporal continuity in Italy was a collapsing of the past with the present. At the museum, the Roman Jewish community is presented as “always” Zionist, as in commentary such as “It is no accident that one of the first, most active sections of the Italian Zionist Federation was founded in Rome, where the group Avoda was formed” ((Di Castro 2010, 61). Clearly, one of the things at stake in the museum’s claim is, intentional or not, an attempt to draw boundaries separating the Italian Jewish Comunità as represented by its leadership in particular from the Italian Jewish community – and, in the process, produce a particular version of Roman Jewish history. The museum’s phrase “side by side with Jewish state” may refer, then, to the period following the actual foundation of the state of Israel.

More pertinently to the present argument, however, the letter signed by Roman Jewish intellectuals, including Levi, was published before the massacres, not in response to them. In other words, opposition among some Italian Jews to Israeli military policy predates the infamous events of Sabra and Shatila. The text also admits, however, that within the community, diverse views with respect to the state of Israel’s government and defense policies coexist.

Nonetheless, there seems to be no space in the museum whatsoever for a discussion of a two-state solution, Israel having risen, like a mythical phoenix, “out of the ashes of the Ottoman Empire” (Di Castro 2010, 34); the Arabs living in the region are typically cast as perpetrators of violence (34), and the Israeli army’s actions as defensive (61). In the section of the museum on Libyan Jews, times in the past when Jews, Christians, and Muslims lived together in peace in the Middle East are trivialized by the suggestion that it was only by paying taxes to the Muslims that Jews were granted a modicum of tolerance. (Interestingly, Julius Caesar, who also taxed the Jews, is instead referred to as their protector [(Di Castro 2010, 36]). While the museum laments that expelled Libyan Jews were never compensated for their lost property, no such suggestion of the need for recompense is made concerning displaced Palestinians. In a film that now plays in the “Emancipation” room, the expulsion of Jews from Libya is referred to as a diaspora and compared to the Spanish expulsion of 1492; no mention is made in the film of the Italian colonization of Libya. In this same film, the “problem” of the 1982 invasion of Lebanon is framed as one of public relations, Israel not having adequately explained to the rest of the world its actions.

As I have already noted in my discussion of its statement on the obligation that men cover their heads, the museum explicitly defines Roman Jews as Orthodox, as this quotation, from the room “From Judaei to Jews” reiterates: “Along with the Orthodox tradition (the point of reference of Italian and Roman Jewry, even if not everyone in private observes every single commandment), modern Judaism comprises other movements. Especially in the English-speaking countries, these movements aim to modernize some exterior aspects of Judaism (Conservative Judaism) or otherwise do not consider themselves strictly bound by tradition (Reform or Liberal Judaism)” (Di Castro 2010, 31). According to Bassi, Italian Judaism today is characterized by “an approximate and selective observance of halakhà” (2011, 252) on the order of what is sometimes called, according to its detractors, “cafeteria Catholicism” (254). Apparently, the museum does not feel authorized to make this claim, and so it fudges the question (and attempts to head off controversy) via the phrase “every single commandment.”

This explanation of a “lived” Orthodoxy that includes a certain flexibility in one’s private practice of Judaism, however, is complicated by the fact that what counts as “every single commandment” cannot be broached by the museum without risk of alienating either Orthodox or reform-minded Italian Jews — though, in characteristic Orthodox fashion, the museum does argue that the Jewish woman plays a particularly marked role in maintaining the 613 mitzvot. (Bassi 2011, 267-68 offers a pointed critique of this type of pseudo-feminism). Orthodoxy is also not in keeping with Levi’s concept of integration; as the museum stresses, Orthodoxy can only be maintained via a closed community that can ensure the maintenance of tradition, particularly in the Diaspora. Additionally: clearly, wearing a yarmulke at all times is not a “private” act, and the exhibitions multiple images of Primo Levi minus a yarmulke provoke a compelling dissonance concerning Italian Jewish identity, regardless of the museum’s stated intentions.

What the museum’s comments on Orthodoxy elide is that, associated with the World Union for Progressive Judaism, reform congregations currently exist in Florence and Milan (where there are two), and, most recently, Rome.37 These congregations are not recognized, however, by the Unione delle Comunità Ebraiche Italiane, or UCEI, the official legal representative of Italian Judaism.38 To quote one blog writer, “To be a Reform Jew in Italy is to struggle with invisibility” (Reliable Narrator, 2010). (Virtually every single time I have taken the museum’s tour of the Synagogue, visitors have been told that all Italian Jews are Orthodox.)

Finally, apparently, in Italy, religious orthodoxy and a critique of the military policies of the state of Israel are incompatible, the UCEI “recognizing the centrality of the State of Israel for contemporary Jewish identity.” Such a centering of Jewish life on the State of Israel is not in keeping with the Levi who valued the hybridity and polyvocality of the Diaspora and the vital role it plays in maintaining a vibrant contemporary Judaism. It also simplifies the complex historical relationship between Italian Jewish identity, Israel, and religious orthodoxy – a relationship explored in the popular Jewish press perhaps most frequently by Anna Momigliano (2015), who most recently has suggested that with the recent death of Rome’s Rabbi Toaff will come “a bowing to Israeli orthodoxy” by young Italian rabbis. As Bassi similarly suggests, “If historically Italian Jewish culture was distinguished by its elasticity and permeability, today it seems increasingly to appear provincial and conformist” (2011 , 20). Finally, this centering of Jewish life on the state of Israel feeds into a general denial of “non-Zionist Jewish experience” perpetrated by the state in pursuit of its highly partisan ends.39

Conclusion

The Levi/Rivers exhibition invites controversy and commentary, but only if one already knows something of the history of Italian (and Roman) Jewry. What it does not do is offer “experiments with exhibition design” in such a way as to “offer multiple perspectives or to reveal the tendentiousness of the approach taken” (Lavine and Karp 1995, 6). On the one hand, the juxtaposition of the Levi exhibition with the other objects in the Novecento (1900s) room seems perfectly appropriate and non-controversial; the Shoah is part of twentieth-century Italian Jewish history, and Levi was not only a survivor of it but an important writer and intellectual figure. On the other hand, while a matter of public record, Levi’s critique of Israeli military policy of the 1980s is likely unknown to non-Italian visitors to the museum, and the myriad, hybrid, and complex ways in which Italian Jews live their identities is not likely to be foregrounded by a museum that both links the past, present, and future of Italian Jews to Zionism and privileges Orthodox Judaism. This, despite the fact that the turn of the last century saw according to one writer a “paradox” characterized by a Jewish community (the writer specifically uses here the lowercase comunità) “completely assimilated yet proud of its particularism” and eager to discuss publicly and with much passion “problems of national-religious identity, of orthodoxy, of a specifically Jewish morality” (Dan Segre 1995, xi). This portrait clearly contrasts with calls to police more rigorously, for signs of leftist and allegedly anti-Semitic critiques of Israel, the Italian Jewish press (Volli, 2013).

Johnathan Flatley (2008) locates in modernist aesthetics “the desire to find a way to map out and get a grasp on the new affective terrain of modernity” (4). For Flatley, that terrain is melancholy. Reading Benjamin, Flatley suggests that “a range of historical processes, such as urbanization, the commodity, new forms of technologized war, and factory work required people to shield themselves from the material world around them, to stop being emotionally open to that world and the people in it” (69). That “shielding” or loss of experience results in a collective and historically specific affect, melancholy. World War II and the Shoah represent one of the most horrific events of the modern era, and, as Levi’s work so clearly illustrates, one of the ways of surviving the lager was precisely to cease feeling empathy for one’s fellow sufferers. Levi provides, among other examples, that of “old Kuhn,” who sat in his bunk saying loud prayers of thanks to God that he had not been chosen for “selection,” while, in the bunk across from him, twenty-year-old Beppo the Greek, who knew that he would die in the gas chamber within a few days, stared fixedly at the light bulb (Levi 2005, 116). As Levi puts it, “Kuhn è un insensato.”

Clearly, like Levi’s work, Rivers’s portraits are a testament to a peculiarly modern form of melancholy – one whose trauma hopefully will never be forgotten and whose loss is experienced consciously. Such an account of irreparable, conscious loss is also at odds with Freud’s (pre-Shoah) understanding of the work of mourning and its eventual “giving up” of the cathexis to the lost object, whereby “deference for reality gains the day” (1917, 166). Freud’s account of the difference between mourning and melancholia, wherein, in the case of the latter, the mourner experiences unconscious loss (166) and displays something “which is lacking in grief – an extraordinary fall in his self-esteem, an impoverishment of his ego on a grand scale” (167) – is likewise flawed. For, in the case of collective devastations like the Holocaust or HIV, melancholy seems not a pathology but rather an appropriate psychic response involving both conscious and unconscious processes (Crimp, 2002). As Flatley (2008) suggests, for Benjamin, “Melancholia is not a problem to be cured; loss is not something to get over and leave behind” (64) or as Derrida (1994) writes, “in fact and by right interminable, without possible normality, without reliable limit” (97).

In his work on spectrality, Derrida argues that certain types of mourning respond “to the injunction of a justice which, beyond right or law, rises up in the very respect owed to whoever is not, no longer or not yet, living, presently living” (97). Similarly, Flatley argues for the importance of “an antidepressive, political, and politicizing melancholia” (27), one whose purpose is to allow for the historicization of affect and presumably a collective recognition of and response to its causes. Flatley specifically privileges aesthetic experiences that produce in the spectator a sense of “self-estrangement,” a de-familiarization of one’s own (melancholic) emotional life that makes possible “a new kind of recognition, interest, and analysis” (80). Following Adorno, he suggests that, in its non coincidence with the historical present, the art work makes possible an alternative to what currently exists (81). It is a form of knowledge that resists instrumentalization. At the same time, from the point of view of its reception in particular, art works “bring affects into existence in forms and in relation to objects that otherwise might not exist” (81), or as Deleuze and Guattari (1994) suggest, “Art undoes the triple organization of perceptions, affections, and opinions in order to substitute a monument composed of percepts, affects, and blocks of sensation that take the place of language” (176).

Rivers’s portraits of Primo Levi are examples of the politicized modernist melancholy charted by Flatley. They are overt attempts to “defamiliarize” Levi by appropriating and altering photographs of the writer and processing them through an aesthetic vocabulary that rewrites both the romantic isolationism of abstract expressionism and what John Berger (1972) has called the “eventlessness” of contemporary advertising, wherein “all real events are exceptional and happen only to strangers” (153). Specifically, in place of publicity’s fascination with surface and, by extension, “a future continually deferred” (153) – one in which the consumer/spectator’s life has been made better via the acquisition of the advertised commodity – Rivers’s portraits of Levi interrupt the hermetic time and space of Renaissance painting. Their refusal to respect what, owing to his status as survivor and the circumstances of his death is, in Levi’s case in particular, the integrity (and sanctity) of the photographic portrait; their playful commentary on perspective; their refusal to let the images speak for themselves – all are precisely an attack on the aura of the work of art, a notion that, in a post-Shoah world, can no longer be tolerated. But in place of Warhol’s postmodern abandonment of critique, Rivers uses the techniques of the mass media, its determination to turn the present into yesterday’s news, in the service of a monumental act of remembrance and mourning (the size of these canvases also being pertinent here.)40

In the chapter of Se Questo è un uomo titled “Sul Fondo,” Levi describes his arrival at the concentration camp. After having been separated from the women and children, the ninety-six exhausted, hungry, and thirsty internees who had managed to survive the initial “selection” were then transported by truck to the camp, la Buna, made to strip naked, and then herded into a shower where they were shaved, sheared of their hair, “disinfected,” handed shoes and a striped uniform, and then forced to run through the snow to a barracks, where they were allowed to dress. Levi writes, “Now for the first time we realized that our language lacked words to express this offense, the destruction of a man” (2005, 23. Out of the more than five hundred Italian Jews in Levi’s convoy, only these ninety some men and twenty-nine women survived this initial selection; 2005,17).

Rivers’s aesthetic of layering and painting over photographs of Levi is a visual analogy for the attempt to “rebuild” the survivor, to restore to him something of his humanness and to harness an antidepressive melancholy for the almost impossible task of historicizing the Shoah and its aftermath. That Rivers received the commission for the portraits of Levi shortly after the writer’s death suggests the ways Levi as icon continues to be inhabited, perhaps haunted, by meaning. Particularly pertinent in this context are Rivers’s formal innovations and the way they re-produce Levi as ghost via “traces” in the form of erasing, photographs of photographs, paintings of photographs, and so forth. Given Israel’s continued military actions in Gaza and the West Bank, Hamas’ response, and the way that, in public debate, certain figures and tropes from the past have recently returned to haunt the present – from an anti-Semitism that holds all Jews responsible for the violence perpetrated by the current Israeli government against the Palestinians, to the equating of all Palestinians with terrorists, to the insistence that any critique whatsoever of Zionism is anti-Semitic, to the continued “morbid attraction for the formula of the ‘victims turned torturers’” (Marzano and Schwarz 2013, 161), – Rivers’s portraits allow Levi to continue to call us to address a wrong. Their exhibition is political in the precise sense of making possible a space from which we might challenge one version of the social world – the claim that the Palestinians as a people don’t exist, or already have a state (Jordan), or the remainder of the litany of excuses provided by the defenders of the violence of various Israeli governments and their United States supporters – with an act of dissensus.

References

Achilli, Michelle. 1989. I socialisti tra Israele e Palestina (dal 1892 ai nostri giorni.) Milan: Marzoratti.

Joan Acocella. 2013. “Who said what.” Pageturner (blog), New Yorker. April 15. www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/books/2013/04/who-said-what.html.

Angier, Carole. 2002. The Double Bond: Primo Levi, A Biography. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

Baroz, Emanel. 2012. “Cronaca di come la propaganda propalestinese abbia mistificato il suo pensiero.” 12 April. Focus on Israel. Francesco Lucrezi. “Le vere parole di Levi.” www.focusonisrael.org/2012/04/12/primo-levi-palestinesi-ebrei/. Accessed August 31, 2013.

Bassi, Shaul. 2011. Essere qualcun altro. Ebrei postmoderni e postcoloniali. Venezia: Cafoscarina.

Belpoliti, Marco, editor. 1997. Primo Levi. Conversazioni e interviste 1963-1987. Turin: Einaudi.

Belpoliti, Marco 2001. “I am a Centaur.” In The Voice of Memory, Primo Levi: Interviews, 1961-1987, edited by Marco Belpoliti and Robert Gordon, translated Robert Gordon. NY: The New Press. Xvii-xxvi.