By Audrey Watters

~

“For a number of years the writer has had it in mind that a simple machine for automatic testing of intelligence or information was entirely within the realm of possibility. The modern objective test, with its definite systemization of procedure and objectivity of scoring, naturally suggests such a development. Further, even with the modern objective test the burden of scoring (with the present very extensive use of such tests) is nevertheless great enough to make insistent the need for labor-saving devices in such work” – Sidney Pressey, “A Simple Apparatus Which Gives Tests and Scores – And Teaches,” School and Society, 1926

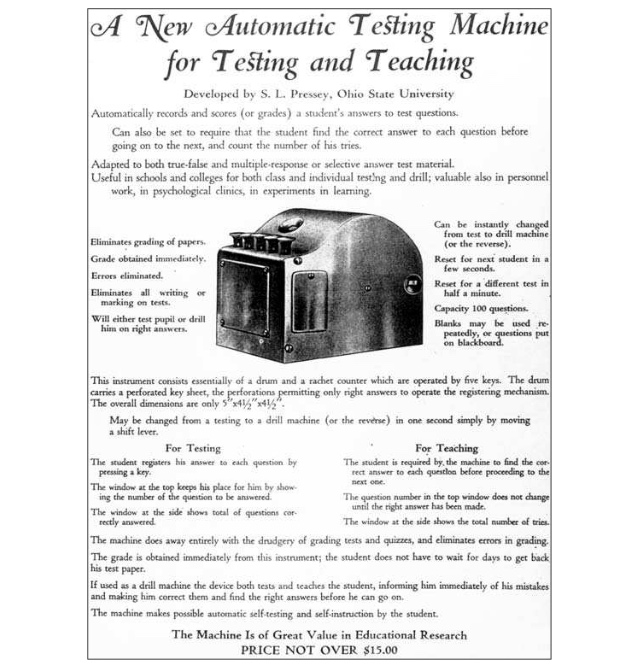

Ohio State University professor Sidney Pressey first displayed the prototype of his “automatic intelligence testing machine” at the 1924 American Psychological Association meeting. Two years later, he submitted a patent for the device and spent the next decade or so trying to market it (to manufacturers and investors, as well as to schools).

It wasn’t Pressey’s first commercial move. In 1922 he and his wife Luella Cole published Introduction to the Use of Standard Tests, a “practical” and “non-technical” guide meant “as an introductory handbook in the use of tests” aimed to meet the needs of “the busy teacher, principal or superintendent.” By the mid–1920s, the two had over a dozen different proprietary standardized tests on the market, selling a couple of hundred thousand copies a year, along with some two million test blanks.

Although standardized testing had become commonplace in the classroom by the 1920s, they were already placing a significant burden upon those teachers and clerks tasked with scoring them. Hoping to capitalize yet again on the test-taking industry, Pressey argued that automation could “free the teacher from much of the present-day drudgery of paper-grading drill, and information-fixing – should free her for real teaching of the inspirational.”

The Automatic Teacher

Here’s how Pressey described the machine, which he branded as the Automatic Teacher in his 1926 School and Society article:

The apparatus is about the size of an ordinary portable typewriter – though much simpler. …The person who is using the machine finds presented to him in a little window a typewritten or mimeographed question of the ordinary selective-answer type – for instance:

To help the poor debtors of England, James Oglethorpe founded the colony of (1) Connecticut, (2) Delaware, (3) Maryland, (4) Georgia.

To one side of the apparatus are four keys. Suppose now that the person taking the test considers Answer 4 to be the correct answer. He then presses Key 4 and so indicates his reply to the question. The pressing of the key operates to turn up a new question, to which the subject responds in the same fashion. The apparatus counts the number of his correct responses on a little counter to the back of the machine…. All the person taking the test has to do, then, is to read each question as it appears and press a key to indicate his answer. And the labor of the person giving and scoring the test is confined simply to slipping the test sheet into the device at the beginning (this is done exactly as one slips a sheet of paper into a typewriter), and noting on the counter the total score, after the subject has finished.

The above paragraph describes the operation of the apparatus if it is being used simply to test. If it is to be used also to teach then a little lever to the back is raised. This automatically shifts the mechanism so that a new question is not rolled up until the correct answer to the question to which the subject is responding is found. However, the counter counts all tries.

It should be emphasized that, for most purposes, this second set is by all odds the most valuable and interesting. With this second set the device is exceptionally valuable for testing, since it is possible for the subject to make more than one mistake on a question – a feature which is, so far as the writer knows, entirely unique and which appears decidedly to increase the significance of the score. However, in the way in which it functions at the same time as an ‘automatic teacher’ the device is still more unusual. It tells the subject at once when he makes a mistake (there is no waiting several days, until a corrected paper is returned, before he knows where he is right and where wrong). It keeps each question on which he makes an error before him until he finds the right answer; he must get the correct answer to each question before he can go on to the next. When he does give the right answer, the apparatus informs him immediately to that effect. If he runs the material through the little machine again, it measures for him his progress in mastery of the topics dealt with. In short the apparatus provides in very interesting ways for efficient learning.

A video from 1964 shows Pressey demonstrating his “teaching machine,” including the “reward dial” feature that could be set to dispense a candy once a certain number of correct answers were given:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n7OfEXWuulg?rel=0]

Market Failure

UBC’s Stephen Petrina documents the commercial failure of the Automatic Teacher in his 2004 article “Sidney Pressey and the Automation of Education, 1924–1934.” According to Petrina, Pressey started looking for investors for his machine in December 1925, “first among publishers and manufacturers of typewriters, adding machines, and mimeo- graph machines, and later, in the spring of 1926, extending his search to scientific instrument makers.” He approached at least six Midwestern manufacturers in 1926, but no one was interested.

In 1929, Pressey finally signed a contract with the W. M. Welch Manufacturing Company, a Chicago-based company that produced scientific instruments.

Petrina writes that,

After so many disappointments, Pressey was impatient: he offered to forgo royalties on two hundred machines if Welch could keep the price per copy at five dollars, and he himself submitted an order for thirty machines to be used in a summer course he taught school administrators. A few months later he offered to put up twelve hundred dollars to cover tooling costs. Medard W. Welch, sales manager of Welch Manufacturing, however, advised a “slower, more conservative approach.” Fifteen dollars per machine was a more realistic price, he thought, and he offered to refund Pressey fifteen dollars per machine sold until Pressey recouped his twelve-hundred-dollar investment. Drawing on nearly fifty years experience selling to schools, Welch was reluctant to rush into any project that depended on classroom reforms. He preferred to send out circulars advertising the Automatic Teacher, solicit orders, and then proceed with production if a demand materialized.

The demand never really materialized, and even if it had, the manufacturing process – getting the device to market – was plagued with problems, caused in part by Pressey’s constant demands to redefine and retool the machines.

The stress from the development of the Automatic Teacher took an enormous toll on Pressey’s health, and he had a breakdown in late 1929. (He was still teaching, supervising courses, and advising graduate students at Ohio State University.)

The devices did finally ship in April 1930. But that original sales price was cost-prohibitive. $15 was, as Petrina notes, “more than half the annual cost ($29.27) of educating a student in the United States in 1930.” Welch could not sell the machines and ceased production with 69 of the original run of 250 devices still in stock.

Pressey admitted defeat. In a 1932 School and Society article, he wrote “The writer is regretfully dropping further work on these problems. But he hopes that enough has been done to stimulate other workers.”

But Pressey didn’t really abandon the teaching machine. He continued to present on his research at APA meetings. But he did write in a 1964 article “Teaching Machines (And Learning Theory) Crisis” that “Much seems very wrong about current attempts at auto-instruction.”

Indeed.

Automation and Individualization

In his article “Toward the Coming ‘Industrial Revolution’ in Education (1932), Pressey wrote that

“Education is the one major activity in this country which is still in a crude handicraft stage. But the economic depression may here work beneficially, in that it may force the consideration of efficiency and the need for laborsaving devices in education. Education is a large-scale industry; it should use quantity production methods. This does not mean, in any unfortunate sense, the mechanization of education. It does mean freeing the teacher from the drudgeries of her work so that she may do more real teaching, giving the pupil more adequate guidance in his learning. There may well be an ‘industrial revolution’ in education. The ultimate results should be highly beneficial. Perhaps only by such means can universal education be made effective.”

Pressey intended for his automated teaching and testing machines to individualize education. It’s an argument that’s made about teaching machines today too. These devices will allow students to move at their own pace through the curriculum. They will free up teachers’ time to work more closely with individual students.

But as Pretina argues, “the effect of automation was control and standardization.”

The Automatic Teacher was a technology of normalization, but it was at the same time a product of liberality. The Automatic Teacher provided for self- instruction and self-regulated, therapeutic treatment. It was designed to provide the right kind and amount of treatment for individual, scholastic deficiencies; thus, it was individualizing. Pressey articulated this liberal rationale during the 1920s and 1930s, and again in the 1950s and 1960s. Although intended as an act of freedom, the self-instruction provided by an Automatic Teacher also habituated learners to the authoritative norms underwriting self-regulation and self-governance. They not only learned to think in and about school subjects (arithmetic, geography, history), but also how to discipline themselves within this imposed structure. They were regulated not only through the knowledge and power embedded in the school subjects but also through the self-governance of their moral conduct. Both knowledge and personality were normalized in the minutiae of individualization and in the machinations of mass education. Freedom from the confines of mass education proved to be a contradictory project and, if Pressey’s case is representative, one more easily automated than commercialized.

The massive influx of venture capital into today’s teaching machines, of course, would like to see otherwise…

_____

Audrey Watters is a writer who focuses on education technology – the relationship between politics, pedagogy, business, culture, and ed-tech. She has worked in the education field for over 15 years: teaching, researching, organizing, and project-managing. Although she was two chapters into her dissertation (on a topic completely unrelated to ed-tech), she decided to abandon academia, and she now happily fulfills the one job recommended to her by a junior high aptitude test: freelance writer. Her stories have appeared on NPR/KQED’s education technology blog MindShift, in the data section of O’Reilly Radar, on Inside Higher Ed, in The School Library Journal, in The Atlantic, on ReadWriteWeb, and Edutopia. She is the author of the recent book The Monsters of Education Technology (Smashwords, 2014) and working on a book called Teaching Machines. She maintains the widely-read Hack Education blog, on which an earlier version of this review first appeared.

Leave a Reply