As a part of b2‘s series on Legacies of the Future: The Life and Work of Edward Said, Wlad Godzich presents “The Stateless and the Proper,” and Stathis Gourgouris on “The Epistemology of Edward Said.”

Search results for: “gourgouris”

-

Stathis Gourgouris on "The Idolatry Post-Secularism"

Follow Stathis’ careful examination of “Idolatry, Prohibition, Unrepresentability,” here, for free download from the Duke UP site and from the last issue of boundary 2, Antinomies of the Postsecular.

This is a meditation on the assertion by Cornelius Castoriadis that “every religion is idolatry.” Idolatry here is configured beyond the conventional understanding of the idol as a concrete object of worship which works within the logic of representation. In monotheism, even the unrepresentable—or, perhaps, especially the unrepresentable—is an idol, an object of worship that is otherwise silenced by a language that claims to worship a nonobject. In this sense, the prohibition of images in monotheism (Bildverbot) is a highly sophisticated mode of idolatry.

-

Erin Graff Zivin and Jonathan Leal–Introduction: (Rhy)pistemologies–Thinking Through Rhythm

Revuelta. Photo credit Inger Flem Soto.

This article is part of the b2o: an online journal special issue “(Rhy)pistemologies”, edited by Erin Graff Zivin.

Introduction: (Rhy)pistemologies–Thinking Through Rhythm

Erin Graff Zivin and Jonathan Leal

“It is the philosophy of [Black] music that is most important.”

Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), Black Music

“You listen to it, the concept might break you.”

Eric B. and Rakim, “I Know You Got Soul”

An experiment: what would happen if a group of academics from fields as varied as, say, philosophy, anthropology, comparative literature, musicology, and dance–many of whom are professional or amateur practitioners of rhythmic artistic forms themselves–thought collectively about the problem of conceptual and theoretical work and its relation to rhythm? How does rhythm—and its attendant art forms—allow us to produce philosophical or conceptual thought? What concepts (ethical, political, aesthetic, or otherwise) emerge from music, dance, sound, motion, and vibration? What began as a series of questions, a collective conceptual and methodological risk, yielded results that could not have been anticipated: an ensemble of theories and insights, in and out of sync, harmonious and discordant.

As a category, rhythm names a sensory interface with the world, an entry point into temporal unfolding across scales: the rapid revolutions of electrons around nuclei, the immeasurably slow deaths of distant galaxies, the ebb and flow of human breathing, the seasonal migrations of birds, the steady build of a tropical storm. Rhythm implies cyclicalities, departures and returns, dramatic interconnections of bodies and systems. Artists who focus attention on rhythm—musicians, dancers, poets, filmmakers—do so in ways that can draw receivers’ attention back to their own bodies, their own senses, their own perceptions of movements, changes, event boundaries.

To think and make through rhythm is to unsettle many of the philosophical inheritances of the imperial West—the atomized, liberal thinking subject divorced from dependency or human relation; the epistemology of the zero point, a thinking that emerges miraculously, without geographic or embodied context; even, and especially, conceptions of “the human” that presume a universal subject devoid of locational or experiential specificity; or, more accurately, implicitly demand accordance to a colonialist hierarchy that measures humanness by way of proximity to an imposed ideal.[1] With that in mind, the concepts that can emerge from a focus on rhythm promise engagements with people, environments, and their attendant histories, promise concepts that can defamiliarize and unsettle knowledge presupposing of a totalizing universal subject, if for no other reason than that they openly emerge from sensory experience, from bodies in and of motion. Rooted in and expressive of the particular—sensoria, situation, movement—such concepts reach for the kinds of integrative and provisional knowledge perhaps only available through relation: what Glissant once called an “open totality.”[2]

Inspired by multidisciplinary tap dance artist and scholar Michael J. Love’s concept of “(rhy)pistemology,” which he understands as “the wealth of cultural knowledge stored in Black American forms of movement and music,” this special issue aims to expand the labor of critical theory and philosophical thought to include embodied forms of knowledge across intellectual, artistic, and cultural traditions. Rather than taking rhythm, music, or dance as an object of theory or thought, we emphasize theory and thought that emerges from or through rhythm. Fumi Okiji’s work on “jazz as critique,” Alexander Weheliye’s commitment to “thinking sound,” Jonathan Leal’s “thought-forms,” and Maya Kronfeld’s notion of spontaneity as political concept are only a few examples of the transdisciplinary and trans-sensory lines of inquiry that inspired this collective conversation.[3]

Drawing together artist practitioners and theorists from a range of disciplinary positions and critical traditions—comparative literature and media, critical theory, philosophy, global Black thought, anthropology, Latinx and Latin American studies, dance, music and sound studies—this special issue pursues the promise of (rhy)pistemological inquiry. Whether through the temporal elasticities of beat tapes, or in-the-moment creative improvisations, or the slow arcs of dancing bodies in midair, or the linearities exploded by language artists, or the interplay of narrative storytelling and shot intercutting in film, and much more, we asked these scholars to consider what happens to extant concepts when stress tested against rhythms across scales, as well as in what concepts can emerge when we attune ourselves more fully to our contexts and, fundamentally, foreground that we always think from our bodies, one breath at a time.

The present collection of work is one result of a series of collaborations and conversations in which a broad, porous community of thinkers and artists have participated. Since 2023, the USC Dornsife Experimental Humanities Lab “Thinking Through Rhythm” study group–which includes graduate students and faculty from Comparative Literature, Latin American and Iberian Cultures, French and Italian, English, American Studies and Ethnicity, Roski School of Art and Design, Kaufman School of Dance, Thornton School of Music, School of Cinematic Arts, and Annenberg School of Communication–has met monthly to read and discuss scholarship on music and rhythm, eat and drink, and to listen to music together. We then convened a seminar at the March 2024 American Comparative Literature Association meeting in Montreal with colleagues from across the country. Yet another variation of the group met at Art Share L.A. in May 2024, where rhythmic performances met academic presentations. Each of these experimental encounters felt both subversive and joyful: presenters and members of the public remarked on the liberating experience of thinking with one’s senses, pushing back against the compartmentalization we often impose on our “professional” selves.

Indeed, each of the participants in this ensemble of thinkers has a unique, eccentric relationship with the conceptual work that often goes by the name “philosophy” or “critical theory” as well as dance, music, and experimental sound. Theorists and practitioners, writers, dancers, music-makers, and listeners, we share a frustration with the way that rhythmic art forms remain objects of study rather than being considered sources of knowledge or sites of conceptual work in themselves. In addition to those whose writing is included here, Natalie Belisle, Gabrielle Civil, Arne De Boever, Jonathan Gómez, d. sabela grimes, Stathis Gourgouris, Edwin Hill, Jane Kassavin, Kara Keeling, Leah King, Josh Kun, Fumi Okiji, Nina Sun Eidsheim, Mlondi Zondi and others have participated in prior and subsequent conversations and gatherings. At the Art Share L.A. event, we were fortunate to count on the participation of artivista Quetzal Flores and composer/pianist Paris Nicole Strother, who accompanied Alex Chávez, Maya Kronfeld, and Michael J. Love in their music-making. The interventions are both conceptual and methodological; indeed, the conceptual underpinnings of artistic practice and expression are laid bare through the troubling of the boundary between what is often categorized as “theory” and “practice.” Thinking through rhythm is necessarily performative, embodied, and transmedial, sonic, visual, and verbal, some of which will be captured through images and links to sound and video in what follows.

The first trio of interventions detail concepts mined from Black American improvisational and rhythmic music and dance: (rhy)pistemologies. In the lead essay, Michael J. Love introduces us to the term he coined to evoke and name the knowledge conveyed through material practices in the Black American vernacular tradition: call and response, active listening, and producing rhythms in real time (what often goes by the name “improvisation”). For Love, (rhy)pistemology—knowing through the rhythm—is inseparable from these traditions. It is also a practice of liberation: similar to Nina Simone’s recollection of brief instances of freedom while making music, Love theorizes the rhythmic, percussive-corporeal practice of tap as a mode of “getting caught up,” accessing a Black queer “elsewhere” (Nadia Ellis)—a utopian future that (as Kara Keeling reminded us in Los Angeles, citing the late José Esteban Muñoz) just might always already exist. Love’s duet with Maya Kronfeld—which they created for the May 2024 meeting—incorporates sampling and looping, improvisational rhythms and theoretical arguments.

Kronfeld’s “Rhythmic Concepts and New Knowledge” argues that rhythmic form produces concepts that are “inchoative knowledge,” drawing upon the work of Immanuel Kant, James Baldwin, and Angela Davis. This not-yet-knowledge does not drive rhythmic practices, but rather emerges from forms-in-motion. She takes Thelonious Monk’s polyrhythmic vernacular in “Straight No Chaser” as an instance of Black experimental rhythmic practice that is “about to be knowledge.” Such insights do not necessarily negate concepts in the Western philosophical tradition, but rather shed crucial light on that for which this tradition fails to account, as well as that which it has violently eclipsed or suppressed. Kronfeld “puts it together” (Elvin Jones’s term for spontaneous composition) in her transmedial theorization: logical argument supplemented, displaced, and oxygenated by her own engagement on keys with the questions posited.

In “So What: Kind of More or Less Than All Blue(s),” Michael Sawyer, for whom Kronfeld is a crucial interlocutor, takes up Toni Morrison’s ekphrastic challenge—“how can I say things that are pictures”—by asking, “how can I write things that are sounds?” Drawing upon the ancient Japanese art form Kintsugi, Sawyer develops a theory of reparative “rememory” (Morrison) in Black cultural expression. Bringing together jagged shards of a broken whole—namely, the generative disruption of the blues in Sonny Rollins’s The Saxophone Colossus and Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue, themselves fragments of other broken, beautiful objects—Sawyer’s close reading of sound is at once shattering and restorative.

We tend to think of rhythm primarily in sonic forms; yet what happens when we are to consider images as possessing their own rhythms? Presented initially at the 2024 American Comparative Literature Association convention in Montreal, the interventions by Jamal Batts, Seth Brodsky, and Eyal Peretz evaluate rhythms of the moving image. In “Black Queer Cadence: Hearing as Diasporic Seeing,” Jamal Batts advances a theory of sound in and as film, specifically, Black queer diasporic cinema in the final decades of the last century. Through close readings of Marlon Riggs’s short film/music video Anthem (1991), as well as the incorporation of poet Essex Hemphill’s voice in Riggs’s Tongues Untied (1989) and Isaac Julien’s Looking for Langston (1989), Batts identifies Afro-diasporic, non-linear queer continuities in visual rhythm, sound, and voice. Drawing on Black experimental film theory (Michael B. Gillespie, Robeson Taj Frazier, Arthur Jafa), philosophy of Black music (Fumi Okiji), and others, he demonstrates the ways in which rhythms work to disrupt the violence of racialized representation, introducing gendered difference into the “unruly intramural sociality of blackness and queerness” which he understands as “entangled, relational, and stereophonic.”

Invoking Fred Moten’s fugitive, fleeting statement to Harmony Holiday about music’s genesis—“in the absence of time, we made rhythm”—Seth Brodsky’s “Losing and Finding Death Drive’s Beat” argues that Freud’s notion has been mischaracterized as a nihilistic death cult, suggesting that music points to a distinct dimension of the drive, beyond nihilism. Through a close reading of the music video to Brittany Howard’s “Stay High,” Brodsky highlights Howard’s rhythmic syncopation, a rhythmic displacement that is untimely in its time travel to past “happy” rhythms (Sam Cooke’s “You Send Me” rather than his “A Change is Gonna Come”) and future bleak horizons: in its visualization of the rhythm and repetition of the workday, the music video would serve as consolation to essential workers toiling long hours in the early months of the pandemic. Yet Brodsky wants to insist upon something more complicated at work. Although the eye can only perceive one rhythmic fact at a time, the ear can process multiple elements of sonic information simultaneously: music fabricates, dilates, and sutures gaps. Brodsky’s theory of music as “a foundational practice of driven beings” exposes the fallacy at the heart of contemporary misreadings of the death drive, inseparable from the pulse of life.

Eyal Peretz’s “Oppenheimer’s Arrhythmia – Between the Cinematic Image and the Atomic Bomb” explores the activation of a new form of time in Christopher Nolan’s film. Distinct from Batts’ analysis of “queer cadence” in experimental cinema, and Brodsky’s consideration of the folding of image into rhythm in Howard’s music video, Peretz’s intervention focuses upon the formal elements of the 2023 film, what he describes as “rhythmic editing.” Identifying the activation of a new temporality set in motion by the conception and detonation of the atomic bomb, he asks whether the rhythmic editing of the cinematic image represents, extends, or interrupts this new temporality. What constative or performative intervention is carried out by Nolan’s arrythmias?

Naomi Waltham-Smith joins Peretz in taking up the relation between rhythm and arrythmia in “Deconstruction’s Hemiolas.” Presented initially as part of the “(Rhy)pistemologies” seminar at ACLA, Waltham-Smith’s essay evaluates the role of rhythm in the work of deconstruction. A scholar of music and philosophy as well as a musician herself, Waltham-Smith demonstrates how the concept’s arrhythmia can be “most passionately moved by” the labor of deconstruction. Indeed, deconstruction’s arrhythmias expose the anarchic concepts as always already more than one: deconstructions. Owed to its syncopated remarking, deconstruction bears affinities with decolonial, Black-radical, anarchist, and queer thought. Incorporating a structure not unlike the 3-against-2 of musical hemiola, she advances a theory of deconstruction’s arrhythmia through close readings of five texts: Derrida’s Glas, Moten’s In the Break, Lacoue-Labarthe’s “L’echo du sujet,” Cixous’s “Le théâtre surpris par les marionettes,” and Bennington’s response to Nancy.

The two concluding pieces return us to the performative, rhythmic thinking tested in Los Angeles. Musician and anthropologist Alex Chávez opened the Art Share L.A. meeting with a performance and talk (“Sonorous Present”), the written component of which has been included in the present issue. During the live event, in conversation with Quetzal Flores and Jonathan Leal, Chávez explored the contemporary conditions of possibility for sonic mourning in a bordered world. Through multimedia performances of selections from his acclaimed 2024 album, Sonorous Present, Chávez elaborated on the rhythms of artistic and scholarly process, highlighting the necessary imbrication of (auto)ethnographic research and related music composition for the type of introspective and community-driven praxis he pursues. His written piece expands these ideas across its three sections—“break,” “qualia,” and “cómplices de luto (accomplices in mourning)”—using a poetics of grief to map contemporary logics of nationalist (American) containments, and in effect, to meditate on political and conceptual possibility. In doing so, Chávez’s work begets questions that resonate across Black studies, border studies, anthropology, and Latinx studies, as well as with the offerings across this special issue: what are the rhythms of our mourning? And how might focusing on them amid the repeating violences of nation-states lead to increased conceptual, political, and artistic freedom?

Finally, “Drone, Groove, and the Specificity of Musical Sound” documents a conversation held between Michael Gallope and Edwin Hill following Gallope’s drone performance, “Region.” Gallope’s electronic, multisensory presentation invited the public into a transformative experience of deep listening, a voyage through space and emptiness. Trained as a musicologist, Gallope has kept his scholarly and artistic lives largely separate until now. Yet the shift of focus from his first book to his second is significant: while the first (Deep Refrains: Music, Philosophy, and the Ineffable), details philosophical reflections on music, the second (The Musician as Philosopher: New York’s Vernacular Avant-Garde, 1958–1978) understands philosophy as emerging from music-making itself. After the performance, Gallope and Hill discussed what it meant for Gallope to perform for the first time in an academic setting, how disciplines and institutions allow for or foreclose the possibility of musical thinking, as well as taking up the central question of “(Rhy)pistemologies”: how are concepts fashioned through rhythmic practices?

Pursuing these questions—enacting this collective experiment across repertoires, methods, and disciplinary structures—has reminded us of the promise and urgency of humanistic inquiry at once artistically engaged and communally rooted. What if? What now, then? At each turn, the project has, in effect, foregrounded the conceptual possibilities of expressive forms that reach beyond insular, rarified knowledge circulation, centering instead those registers of criticism, theory, and multimedial expression that center bodies and minds in motion, alive to the sinew of experience. Our work together produced its own rhythms, its own cycles of affect and analogy, critique and convergence, and this, in its way, has been a reminder of what has long been the case in those increasingly necessary spaces where conscious relation is held in high esteem. Provisionally, then: to think through rhythm is to attend to relation and greet the world as it has been, is now, and hope it can be—at distance from those forms of thought that would deny the world.

Listen to it. The concept might break you.

[1] See Sylvia Wynter, Hortense Spillers, Vijay Iyer, Fred Moten, among many others. For a recent example, see Iyer’s 2025 lecture at the USC Dornsife Experimental Humanities Lab, “Musicalities: Scenes of Sonic Social Life.”

[2] Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation. Trans. Betsy Wing. (University of Michigan Press 1997), 171.

[3] In recent decades, scholarship in Black studies, cultural history, and music studies has expanded the conversation around these issues immensely. For a few immediate touchstones, see Fred Moten’s In the Break, Alexander Weheliye’s Phonographies, Shana Redmond’s Anthem, Josh Kun’s Audiotopia, R.A. Judy’s Sentient Flesh, Brent Hayes Edwards’ Epistrophes, Emily J. Lordi’s The Meaning of Soul, and Nina Sun Eidsheim’s Sensing Sound.

-

Matti Leprêtre–Modernity, Lebensreform, and MAGA’s Grassroots: On Some Economic Contradictions of Trumpism

This Intervention is published as part of the b2o Review’s “Stop the Right” dossier.

Modernity, Lebensreform, and MAGA’s Grassroots: On Some Economic Contradictions of Trumpism

Matti Leprêtre

The MAGA movement presents a paradox: it rails against globalization and modernity, yet it is led by billionaire capitalists who thrive on both. This contradiction echoes the coalition that brought Hitler to power—a mix of industrial elites and working- to middle-class Germans drawn to the reactionary, anti-modern rhetoric of the Lebensreform. The same fractures that ultimately weakened that coalition could be exploited today to challenge MAGA’s hold on power. But if left unchecked, its path is just as clear: when economic promises fail, all that remains is the persecution of minorities.

*

Trump, Hitler, and Weimar: Rethinking the German-American Parallel

There is something deeply amiss in the way the memory of Nazi Germany is invoked in contemporary debates about American politics. Trump’s bid for a second term has inspired countless comparisons between him and Hitler—comparisons that, aside from their historical dubiousness, merely stimulate MAGA supporters’ libidinous drive to trigger woke liberals. Instead, there is value in fixating not on the Nazi era from 1933 onward, but on the more fluid, transformative period of 1920s Germany.

In that turbulent decade, a wounded cultural pride lingered after the 1918 defeat, and deep anxieties about losing world-power status permeated society. Gender-based challenges to the patriarchal order, the growing assertion of gay rights, and other emancipation movements met with fierce resistance from traditional authorities and conservative reactionaries. Most importantly, the profound crisis of modernity caused widespread anti-modern sentiments—all of which eventually coalesced into the conditions that allowed the Nazi Party to seize power.

There is little doubt that dealing with the first element—hurt cultural pride—is the chasse gardée of the Republican Party, while the struggle for emancipation remains the preserve of the Democrats. As an outsider, I have long been struck by how readily the U.S. left has allowed anti-modern sentiments to be co-opted by Republicans, with figures like Steve Bannon at the helm.

The caution is understandable. Anti-modern sentiments have long been associated with the rise of fascism in Europe and Nazism in particular. Yet before these ideas became the exclusive domain of the Nazis, they circulated freely across the political spectrum for more than half a century. They not only fueled nationalist and anti-Semitic currents but also underpinned a proto-environmentalist critique of modernity as part of a popular movement that came to be known as the Lebensreform.

Antimodernity before Fascism: The Ambivalent Heritage of the Lebensreform

Emerging in the latter half of the 19th century in a rapidly industrializing Germany, the Lebensreform (or reform of life) movement chiefly championed the “return to nature,” in a country where factories mushroomed across the landscape. For some, this “return” meant rejecting modern medicine in favor of natural remedies; for others, it meant embracing long hikes in the mountains; and for still others, it meant seeking an alternative to a worldview that treated nature and humanity as mere cogs in the economic machine.

Though largely driven by the bourgeoisie, the movement mounted a sharp critique of globalization, the dehumanization of factory labor, and the environmental devastation wrought by capitalist accumulation—even giving birth to Germany’s first utopian communities. For all these reasons, the Lebensreform has been described as the matrix not only for Nazism but also for future environmentalist and anti-globalization movements.

As a historian of Germany, I have always been struck by the parallels between the Lebensreform critique of globalization and the rhetoric of the grassroots of the MAGA movement. The far-right’s critique of “globalists” finds a clear parallel in the Lebensreform’s disdain for the emerging globalized world; and Bannon’s scathing attacks on technological progress, Elon Musk, and the “broligarchs” are reminiscent of earlier Lebensreform-ist critiques of technological advancement. Likewise, the widespread rejection of academic medicine and science—exemplified by the nomination of Robert Kennedy Jr. as Health Secretary—bears an uncanny resemblance to the alternative medical views championed in Germany a century ago. Yet, because of their common historical root in the Lebensreform, these elements also appear in leftist anti-globalization movements.[1]

Beyond Cultural War: Reclaiming the Critique of Globalization

I am not equating anti-globalization leftist movements with MAGA, nor suggesting that an alliance between the two is possible or desirable at this point. MAGA’s anti-modernity departs sharply from the traditional leftist critique—with its crude racism, nationalism, Christian fundamentalism, and mysticism. Yet these tensions were already present in 1920s Germany, and largely because the German left failed to harness these popular energies, a significant portion of the movement fell into Nazi hands. This historical precedent suggests that if a new left is to succeed where the old faltered against the far right, it should develop a critique of globalized capitalism able to prevent the growing number of those left behind by globalization from joining MAGA, or even capture the grassroots energies now under the MAGA banner.

For that, the left has a rich political repertory to draw upon. The critique of globalization and capitalist modernity has never been primarily a far-right one. From the first utopian communities to the “small is beautiful” movement of the 1970s, from Ivan Illich’s critique of biomedicine to the Our Bodies, Ourselves of the Boston Women’s Health Group Collective, from the anti-G8 protests of the 2000s to post- and decolonial propositions for finding an alternative to—or even an exit from—modernity, a range of options exists, more or less appealing, more or less viable today, but all worth considering for the emergence of a New Left. What is certain is that discarding the slightest critique of academic medicine as a conspiracy theory, scorning even the smallest enthusiasm for a life lived closer to nature as reactionary, and claiming to be “progressive” at all costs in a world so deeply embedded in a crisis of modernity will only seem repulsive to the growing number of people who see techno-industrial progress and globalized capitalism as the main cause of their torment.

It is only a question of time before MAGA’s disparate coalition begins to disappoint its working- and middle-class members. A coalition built around an omnipotent, transhumanist tech billionaire and a cadre of like-minded oligarchs will most likely do very little to address the real impacts of globalization and technological change on millions of American workers. Trump’s wavering stance on tariffs reflects this very contradiction: every time he tries to deliver on the aspirations of his working-class base, he is reined in by the cast of oligarchs he ultimately serves. To conceal this, the oligarchs have to double down on the one fight in which they can seem to stand with “the people” against “the regime”—cultural war. In effect, the only arena in which the Trump administration can thrive is in the persecution of minorities.

This, too, was the case in 1920s Germany. The coalition that eventually propelled Hitler to power brought together Lebensreform-inspired anti-modern peasants, factory workers, and middle-class employees, alongside wealthy industrialists terrified of the rising tide of communism and emancipatory movements.[2] This uneasy alliance forced the Nazis to adopt a vehement anti-modern rhetoric to placate their grassroots supporters, while simultaneously embracing cutting-edge techno-industrial policies and deepening the logics of global capitalism. Even the Nazis’ de-globalizing measures emerged only when war loomed and autarky became a national security imperative. Their only ideological common ground was the cultural war they waged against emancipatory movements and, most notoriously, against ethnic and religious minorities—a war that would ultimately pave the way for the Shoah.

So far, Democrats have largely fallen into the trap of fighting Republicans on the terrain of cultural war, the only domain in which MAGA’s coalition remains united. While there is indeed an urgency in responding to the Trump administration’s “flood the zone” strategy and its constant targeting of minority rights, history suggests that a more promising strategy would be to stop fighting solely on the terrain of values and start exposing the internal fractures within MAGA’s vision—particularly its conflicting ideas about globalization, technology, and the meaning of life and work. At the same time, they must put forward viable alternatives; ones that embrace more localized, low-tech ways of living.

An Uncomfortable Dialogue: Lessons from the Yellow Vests

Engaging in a dialogue with people currently attracted by MAGA’s anti-modern rhetoric might feel uncomfortable at first. In France, the left faced a similar unease in 2018 when the Yellow Vest movement erupted. Initially a reaction against an oil tax, the movement soon broadened to encompass grievances common to MAGA’s grassroots—demands for a decent life in one’s village, resistance to the concentration of services in big cities, a rejection of unrestrained globalization, and a critique of the ultra-connected, ultra-mobile elite’s way of life. In retrospect, it became clear that the movement had emerged from those left behind by globalization.[3] The French left, initially repulsed by the protests—deeming them the product of politically illiterate people with no clear views on immigration, gender politics, and ecology—gradually joined the movement, imposing leftist slogans and even sidelining its more overtly far-right, violent elements.

The convergence was by no means easy. A sensible component of the Yellow Vests eventually turned back to the far right as the movement faded—partly due to quasi-military repression and partly because some of its most basic revendications were fulfilled. Yet this turn toward Marine Le Pen also occurred because the institutional left was unable to articulate a critique of modernity compelling enough to keep the Yellow Vests from falling into the open hands of France’s MAGA equivalent. As uncomfortable as this dialogue might feel, it is a necessary one.

Coda: What’s Left of the Left?

Debates after the election have focused on whether the Democrats should have leaned further to the left or more toward the center to win the votes they needed to secure victory. This assumes that political positions can be summed up along a single line from far right to far left. Yet, depending on the issues considered, there is sometimes less distance between an anti-globalization leftist activist and a MAGA grassroots supporter than between that same activist and a centrist Democrat. MAGA supporters may soon come to see that the strongest “regime” of all is the one that binds together the guardians of globalized capitalism—a regime spanning large swathes of both the Democratic and Republican parties, with Trump and Musk as its most zealous artisans.

One can only hope that the American left will have made its aggiornamento by the time this day comes, to welcome the disillusioned adherents of Trumpism. The Democratic Party’s current stance—as the last firewall between Trump’s erratic populism and Wall Street, and as the staunch defender of free trade and the post-1945 global economic order—raises serious doubts about the American left’s ability—or willingness—to reclaim a critique of globalization that should always have remained central to any party still dreaming of itself as the voice of the working class[4].

Matti Leprêtre is a Teaching and Research Fellow at Sciences Po Paris and a PhD candidate at the EHESS. His dissertation examines the history of medicinal plants in the German Empire from the 1880s to 1945. He trained in postcolonial studies as an undergraduate and earned a dual degree from Sciences Po and Columbia University in 2017. He has been invited to present his research at a wide host of institutions across France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States, including Oxford and Harvard. His work has appeared in several edited volumes and journals such as the Journal of the History of Ideas. He is currently co-editing an edited volume and a journal special issue on the relationship between health, nature, and the pharmaceutical industry.

Works Cited

Chapoutot, Johann. Les irresponsables. Qui a porté Hitler au pouvoir ? Paris: Gallimard, 2025.

Gourgouris, Stathis. Nothing Sacred. New York: Columbia University Press, 2024.

Porcher, Thomas. Les délaissés: Comment transformer un bloc divisé en force majoritaire. Paris: Fayard, 2020.

Siegfried, Detlef, and David Templin, eds. Lebensreform Um 1900 Und Alternativmilieu Um 1980: Kontinuitäten Und Brüche in Milieus Der Gesellschaftlichen Selbstreflexion Im Frühen Und Späten 20. Jahrhundert. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2019.

[1] Siegfried, Detlef and David Templin, eds. Lebensreform Um 1900 Und Alternativmilieu Um 1980: Kontinuitäten Und Brüche in Milieus Der Gesellschaftlichen Selbstreflexion Im Frühen Und Späten 20. Jahrhundert. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2019.

[2] Chapoutot, Johann. Les irresponsables. Qui a porté Hitler au pouvoir ? Paris: Gallimard, 2025.

[3] Porcher, Thomas. Les délaissés : Comment transformer un bloc divisé en force majoritaire. Paris: Fayard, 2020.

[4] For a recent example of what a leftist criticism of globalization could be, see Gourgouris, Stathis. Nothing Sacred. New York: Columbia University Press, 2024.

-

Martijn Konings–The Modern Money Tangle: An Introduction

This article is part of the b2o: an online journal Special Issue “The Gordian Knot of Finance”.

The Modern Money Tangle: An Introduction

Martijn Konings

It is increasingly evident that the existing economic policy paradigm is a recipe for ongoing economic stagnation, political polarization, and ecological degradation. But this growing awareness often seems peculiarly inconsequential, incapable of driving even minor shifts in the most conspicuously harmful policy settings, including governments’ enormous subsidies for fossil fuel extraction and the near-perfect exemption of extreme private wealth from taxation. Even as electoral systems have become almost as volatile as the stock market, it seems that, when it comes to economic policy, the political center holds, inexplicably.

We tend to call that paradigm “neoliberalism”. The epithet was first used by academics. But, as during the decade following the Global Financial Crisis wider communities of observers found themselves increasingly puzzled by the immunity of economic policy to feedback from social and ecological systems, the label became used more widely (Slobodian 2018, Monbiot and Hutchinson 2024). The problem, by this account, consists in politicians’ and policymakers’ unexamined belief in an expanded role for market mechanisms as the obvious solution to any and all social problems. Moreover, that erroneous belief is self-reinforcing, as the persistence or worsening of social problems is only ever taken to mean that not enough market efficiency has yet been applied.

In the social sciences themselves, neoliberalism has become a contested concept. A general definition – neoliberalism as the reformulation of a classic liberalism in response to the rise and crisis of Keynesianism – is unlikely to encounter many objections. But the critical force of the neoliberalism concept is premised on a more specific claim – namely, the ability to capture the diminishing role of the state and the expansion of the market. It is not at all clear, however, that such a shift in society’s center of gravity, from public to private, has taken place. The very period during which the concept of neoliberalism established itself as a common descriptor was also the era of “quantitative easing” (asset purchases by the central bank) and “macroprudential regulation” (concerning itself not just with the health of individual firms but with macro-level stability) during which Western governments took on an unprecedented level of responsibility for maintaining the balance sheets of large financial institutions (Tooze 2018, Petrou 2021). Entirely contrary to what the neoliberal schema would suggest, the functioning of government institutions has become deeply entangled with the expanded reproduction of private wealth (Konings 2025).

Supported by the significant historical and conceptual nuance that recent scholarship has provided, some have argued that the neoliberalism concept can accommodate such developments. But such qualifications undercut the critical thrust of neoliberalism as an off-the-shelf diagnosis of our current predicament. Others have gone further in questioning the suitability of traditional categories of state and market for capturing structures of power and exploitation that appear simultaneously archaic and futuristic. Neoliberalism, from such a perspective, may simply have buckled under the weight of its own contradictions, and we are now seeing a transition to a very different kind of society – neo-feudalism or technofeudalism (Dean 2020, Varoufakis 2024). Such takes align with the self-image of many Silicon Valley billionaires, who often see themselves less as capitalist entrepreneurs than as the founders of new dynastic bloodlines. But treating such heroic or nihilistic self-stylings as reliable guides to current transformations rather than publicly lived mental health struggles may well be a symptom of what Stathis Gourgouris (2019: 144) understands as social theory’s own “monarchical desire”.

A more helpful angle has been advanced by Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), a perspective that understands economic value as a public construct and found considerable traction by pointing out that such public capacities for value creation had been appropriated by the property-owning class (Wray 2015, Kelton 2020). Taking a leaf from the Marxist book of dialectical historical change, MMT authors propose liberating the machinery of public value creation from the pernicious regime of property relations that it has been made to serve and instead to press it into serving “the birth of the people’s economy”, in the words of Stephanie Kelton (2020). If governments can afford to bail out banks, they can fund programs with actual social value.

MMT precursor Abba Lerner (1943, 1947) viewed his perspective on money as a public token as nothing more than a rigorous statement of the assumptions underpinning Keynes’ General Theory. Keynes himself had tried to make his work acceptable to establishment opinion by concentrating primarily on the role of fiscal policy, leaving the overarching financial structure of the capitalist economy go unquestioned. Even during the heyday of Keynesian hegemony, attempts to wield the public purse were always constrained by the fact that control over monetary policy settings was firmly in the hands of central banks (Major 2014, Feinig 2022). That was a key institutional precondition for the rise of neoliberal inflation targeting. But the absurdity of putting monetary decision-making beyond democratic control became fully evident following the Global Financial Crisis, when central banks made permanent an extensive range of subsidies and guarantees for the holders of financial assets, while governments tightened the public purse strings by cutting social programs.

In this context, arguments that had long been dismissed as crank theory were able to bypass the censure of mainstream economics and find purchase in the public sphere. The vicious response of mainstream economics to the popularity of MMT has done more to underscore than to refute the salience of its provocation – that there exist no actual economic reasons why we can’t repurpose the institutions of the bailout state, away from the gratuitous subsidization of private wealth accumulation and towards shared prosperity.

Finance, MMT understands, holds no secret: it’s just a ledger of society’s transactions and commitments. And if these records are in principle as transparent as any other system of accounts, then what is there to prevent the public and its representatives from taking charge and correcting the perverse misallocations embedded in the current system? According to MMT, the main obstacle here is the flawed, arch-neoliberal idea that governments, like private households, need to “balance the books”. Politicians who operate under the pernicious influence of neoliberal ideology do not recognize that governments are sovereign institutions issuing their own currency and are not subject to the same discipline as households. Adding insult to injury, the principle of public austerity is always readily suspended when banks need bailouts – and invariably reinstated again once the danger of system-level meltdown has passed.

MMT has adopted a very literal reading of neoliberalism, imagining that the force of its ideological obfuscations is the main obstacle to repurposing the mechanisms of quantitative easing for the advancement of the people. In reality, the problem runs deeper. The public underwriting of private balance sheets has a long history. From the mid-twentieth century it served as a key instrument for governments to manage the contradictions of welfare capitalism. During the 1970s, neoliberal ideas of fiscal and monetary austerity became influential not because of their ideological strength, but because they provided a way to manage the inflationary pressure produced by risk socialization. That permitted the routinization of bailout and backstop policies, which culminated in the intravenous liquidity drip-feed that large banks enjoy at present.

That arrangement also has deeper social and political roots than it is typically credited with. Government subsidization of asset values is a major factor responsible for the rise of the “1%”, but it has also underpinned a broader reconstruction of middle-class politics, away from wage expectations to capital gains (Adkins, Cooper and Konings 2020). The nineties represented the high point of this asset-focused middle-class politics, when rising home and stock prices delivered benefits widely enough to give credence to the promise of inclusive wealth.

The trickle-down effect has now come to a halt, but that fact does not by itself undo the ideological or institutional structure of the backstop state. The allocation of public resources has become intertwined with the private wealth accumulation in an endless number of ways that are not easily unwound. The idea that governments can do things themselves, without having to put in place complex financing constructions to mobilize private capital and incentivize the doing of said thing by others, has become so incomprehensible in the bourgeois public sphere that there simply no longer exists a straightforward channel for translating social priorities into public spending priorities. What binds the machinery of policymaking to the power of finance is not a set of discrete ties but rather something akin to a Gordian knot.

How to undo, loosen, transform, or bypass that knot? The recent past offers some clues. Since the Covid crisis, modern money has powerfully expressed both its public and its private character. When emergency struck, governments were instantly capable of doing all the things that politicians and experts routinely advise are just not possible. By expanding the safety net beyond the financial too-big-to-fail establishment, they orchestrated a “quantitative easing for the people”, in the words of Frances Coppola (2019). The world’s most powerful central banker, Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell, conceded that there were no real technical limits to the possibility of getting money in the hands of people who needed it (Pelley 2020). Almost overnight, MMT went from indie darling to mainstream pop star. “Is this what winning looks like?”, the New York Times wondered (Smialek 2022). Many declared the end of the neoliberal model.

But before too long, inflation surged, and discourses insisting on strict limits to the use of public money and credit returned to prominence. The discipline thus meted out has been extremely uneven. Central banks across the world have increased interest rates to slow down growth and employment, but for bankers and asset owners the edifice of quantitative easing and liquidity support remains firmly locked in place. Treasuries have similarly tightened the purse strings, swiftly undoing the broadened financial safety nets and undertaking deep cuts in social programs and public education even as they continue to increase spending on the military and corporate tax breaks.

MMTers and other progressives have not failed to call out the hypocrisy, and neoliberal nostrums about the importance of balanced budgets no longer enjoy the same intellectual authority that they once did. But it often seems as if that hardly matters – that the sheer exhaustion of neoliberalism as an intellectual paradigm merely serves to make a mockery of the idea that policy could change in a material way. We can all see that the emperor is not wearing anything, and yet we’re in the midst of a powerful restoration of economic orthodoxy, relentlessly socializing the risk of the largest players while inflicting tight monetary and fiscal policy settings on the rest of the population.

MMTers have allied with other heterodox economists to rebut mainstream arguments for deflationary policy (Weber and Wasner 2023). Inflationary pressures, they argue, had their origins in specific events such as supply-chain disruptions, and should be addressed by targeting those sources – not by carpet-bombing the economic system at large. Such arguments invoke a long history of Keynesian supply-side thinking that aims to undercut inflationary pressures in ways that do not require the central bank or the treasury to deploy their crude instruments of general deflation. The last time such a progressive supply-side agenda had made waves was during the nineties, when Democrats positioned such ideas as an alternative to Reagan’s right-wing supply-side agenda. Then, they became allied to spurious claims about a new economy and ended up providing ideological cover for Clinton’s embrace of fiscal austerity. This time, such ideas synced with the Biden’s administration’s interest in a more active industrial policy meant to counter the economic stagnation that had become evident during the previous decade and to tighten the strategic connections between key economic sectors and America’s geopolitical interests.

While the recentering of the national interest has allowed Keynesian ideas to enjoy greater influence, it has also reinforced the blind spot that has historically plagued that paradigm and that MMT had sought to correct. Even as fiscal and regulatory policy have become fully yoked to the needs of financial assets holders for minimum returns – a dependence that Daniela Gabor (2021) has referred to as the Wall Street consensus, dominated by an asset manager complex that demands comprehensive derisking for any and all projects it invests in, what fell by the wayside with the rise of Bidenomics is a critical focus on the economy’s financial infrastructure as an object of democratic decision-making.

Indeed, the Biden administration has been eager to disavow any interest in in challenging the autonomy of the Federal Reserve – one of its preferred ways to signal that there are “adults in the room” who take advice from experts. In this way, it has left the field open to the far right, which intuits much more readily that the advocates of independent central banking are false prophets, and it has made greater political control over monetary policy one of the key points of its blueprints for a more fascist future such as Project 2025. A progressive agenda that fails to engage that terrain, on which are situated the monetary drivers of the escalating concentration of asset wealth, will be unable find much sustained traction.

MMT has shown us where we need to look – where to direct our attention and bring the struggle. But its wish to beat mainstream economics at its own scientistic game, by advancing objectively better policies rooted in superior expertise, prevents it from recognizing what an effective political engagement might involve. The contributions to this forum resist the temptation to imagine alternatives as if any are readily available. Instead, they examine modern money as a complex tangle, composed of an endless range of dynamically evolving strategies and alliances that straddle any divide between public and private. The financial knot is tighter in some places than in others, but neither orthodox economics nor MMT gets the pattern into sufficiently sharp focus to see the openings and fissures.

In that sense, we should perhaps consider ourselves as occupying the mental space that Keynes did after he completed A Treatise on Money (Keynes 1930), which catalogued the extraordinary expansion of liquid financial instruments during the early twentieth century but had left him uncertain about the meaning of all this. When several years later he wrote the General Theory, his mind was on the day’s most pressing questions, above all the dramatic collapse in output and employment that had occurred during the previous years. While he recognized that such volatility could only occur in a monetary economy, he nonetheless considered it justifiable to let finance drop “into the background” (Keynes 1936: vii). Lerner viewed that as an infelicitous move, sensing correctly that it kept open the door to the restoration of an economic orthodoxy eager to sacrifice human livelihoods at the abstract altar of financial property. The contributions presented here (presented first at a symposium on the Gordian knot of finance held at the University of Sydney, generously sponsored by the Hewlett Foundation), take a step back and linger with the more open-ended curiosity that drove Keynes’ earlier engagement with the institutional logic of financial claims. How has the knot of modern money been tied?

Stefan Eich’s contribution examines money’s constitutive duality, the fact that it is public and private at the same time. He draws attention to the structural similarity of perspectives that think of the financial system as either primarily public or primarily private, and, engaging with MMT as well as other strands of “chartalist” theory, he argues that money is best seen as a constitutional project. The fact that money is at its core both public and private means that political openings always exist, even if those are never opportunities to reconstruct the financial structure from scratch.

Amin Samman asks what it is about the financial system that makes it so resistant to rational public policy intervention. To this end, he draws attention to the role of fictions in the functioning of finance – when speculative projections fail, the response is not sober reflection but a feverish acceleration of their production, eventuating in the installation of the lie as the modus operandi of capital. More earnest, truth-observant policymakers occupy a structurally impossible position, on the one hand interfacing with the delirious virtuality of capitalist finance and on the other attempting to be responsive to rational criticisms.

Dick Bryan argues that a preoccupation with how to undo or cut the Gordian knot may be misplaced. For each bit of loosening we achieve, capital has tricks up its sleeve to tighten its grip. Instead of focusing too much on the knot itself, we might think of ways to slip past it by designing financial connections that may not instantly become entangled in existing networks and their power concentrations. Challenging any clear-cut distinction between money and asset, he argues that crypto currencies could be designed to play that role.

Janet Roitman takes a different look at the image of the Gordian knot as a global imperial structure, and she asks whether it in fact attributes too much efficacy to the power of finance. While acknowledging the strength of the international currency hierarchy, she shows that dynamics challenging the dollar system arise from within the dynamic of capitalism itself. New financial technologies are instruments of economic competition, and in that capacity, they offer new opportunities for exploitation but inevitably also for the loosening of constraints, however limited or compromised such emancipation may be.

While Roitman turns our attention to the fissures in the global financial knot, Michelle Chihara concludes the forum by pointing out a major kink in the heartland of modern money. She argues that, for all our fascination with the ghost towns that the bursting of the Chinese real estate bubble produced, vacant property is a key aspect of the functioning of contemporary global capitalism. The jarring combination of vacant apartments serving as subsidized storage for transnational wealth on the one hand and a rapidly growing population of homeless and underhoused on the other, is giving rise to new forms of protest, reminding us that the grip of money is rooted in the compliances of everyday life.

Taken together, the contributions collected here shed light on different aspects of the tangle of promises, claims and commitments that constitute modern money. Such a perspective militates against the promise of a neatly executed, wholesale policy shift to reorient the economic system, but that does not entail a hard Hayekian anti-constructivism as the only alternative. MMT might be likened to a subject of psychoanalysis that, upon realizing that the world holds no deep secret, declares itself cured – but, when venturing back out, finds that its relationship to that world has undergone little practical change. It still has to do the work of deconstructing, transforming, or otherwise navigating the actual web of fictions, promises, lies, and obfuscations that it has built. In few areas of life is such thoughtful deconstruction more imperative than in our relationship to modern money, which is structured by so many layers of miseducation and misapprehension that transforming its practical operation is necessarily as much about revising our understanding as it is about getting our hands on the institutional machinery of its creation.

Martijn Konings is Professor of Political Economy and Social Theory at the University of Sydney. He is the author of The Emotional Logic of Capitalism (Stanford University Press, 2015), Neoliberalism (with Damien Cahill, Polity, 2017) Capital and Time (Stanford University Press, 2018), The Asset Economy (with Lisa Adkins and Melinda Cooper, Polity, 2020), and The Bailout State: Why Governments Rescue Banks, Not People (Polity, 2025).

References

Adkins, Lisa, Melinda Cooper and Martijn Konings. 2020. The Asset Economy, Polity.

Brown, Wendy. 2015. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution, Zone.

Coppola, Frances. 2019. The Case For People’s Quantitative Easing, Polity.

Dean, Jodi. 2020. “Neofeudalism: The End of Capitalism?”, Los Angeles Review of Books, May 12.

Feinig Jakob. 2022. Moral Economies of Money: Politics and the Monetary Constitution of Society, Stanford University Press.

Gabor, Daniela. 2021. “The Wall Street Consensus”, Development and Change, 52(3).

Gourgouris, Stathis. 2018. The Perils of the One, Columbia University Press.

Kelton, Stephanie. 2020 The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy, PublicAffairs, 2020.

Konings, Martijn. 2025. The Bailout State: Why Governments Rescue Banks, Not People, Polity.

Lerner, Abba P. 1943. “Functional Finance and the Federal Debt”, Social Research, 10(1).

Lerner, Abba P. 1947. “Money as a Creature of the State”, American Economic Review, 37(2).

Keynes, John Maynard. 1930. A Treatise on Money, Cambridge University Press.

Keynes, John Maynard. 1936. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Major, Aaron. 2014. Architects of Austerity: International Finance and the Politics of Growth, Stanford University Press.

Monbiot, George and Peter Hutchison. 2024. Invisible Doctrine: The Secret History of Neoliberalism, Crown.

Pelley, Scott. 2018. “Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell on the coronavirus-ravaged economy”, CBS News, May 18.

Petrou, Karen. 2021. Engine of Inequality: The Fed and the Future of Wealth in America, Wiley.

Slobodian, Quinn. 2018. Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism, Harvard University Press.

Smialek, Jeanna. 2022. “Is This What Winning Looks Like?”, New York Times, February 7.

Tooze, Adam. 2018. Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World, Viking.

Varoufakis, Yanis. 2024. Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism, Melville House, 2024.

Weber, Isabella M. and Evan Wasner. 2023. “Sellers’ Inflation, Profits and Conflict: Why Can Large Firms Hike Prices in an Emergency?”, Review of Keynesian Economics, 11(2), 2023.

Wray, L. Randall. 2015. Modern Money Theory: A Primer on Macroeconomics for Sovereign Monetary Systems, Palgrave Macmillan.

-

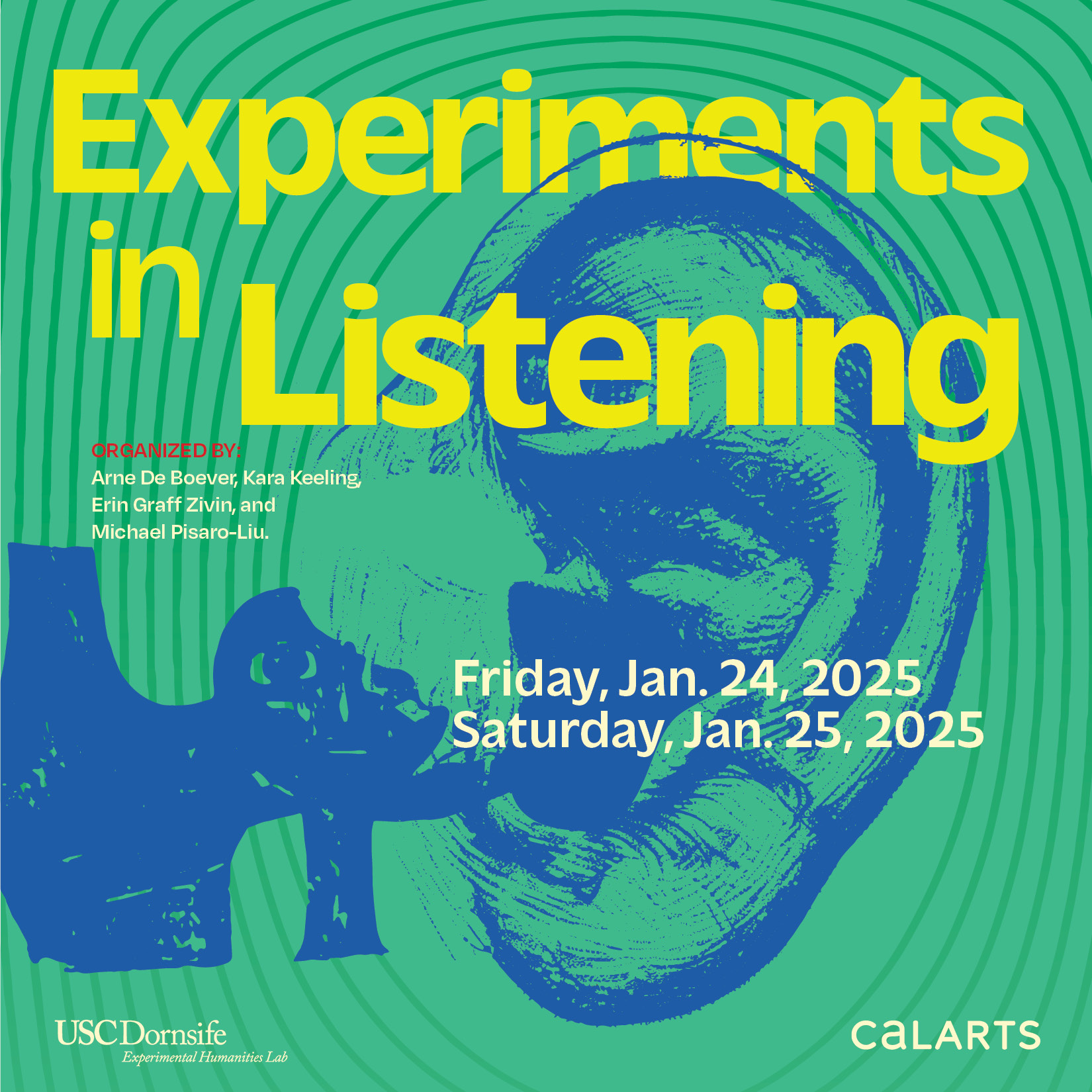

Experiments in Listening–boundary 2 annual conference

**PLEASE NOTE THE LOCATION CHANGE FOR SATURDAY DUE TO THE HUGHES FIRE**

Experiments in Listening

Friday, January 24-Saturday January 25, 2025

University of Southern California and California Institute of the Arts

Supported by the MA Aesthetics and Politics program and the Herb Alpert School of Music at the California Institute of the Arts; the USC Dornsife Experimental Humanities Lab; the Division of Cinema and Media Studies at USC’s School of Cinematic Arts; and boundary 2: an international journal of literature and culture.

With additional support from the Dean of the School of Critical Studies at CalArts; the USC Dornsife Graduate Dean and Divisional Vice Dean for the Humanities, the USC Department of Comparative Literature, and the USC Department of English.

This event is also supported by the Nick England Intercultural Arts Project Grant at CalArts.

Organized by Arne De Boever, Kara Keeling, Erin Graff Zivin, and Michael Pisaro-Liu.

“To anyone in the habit of thinking with their ears…” Thus begins Theodor W. Adorno’s famous essay “Cultural Criticism and Society”. But what does it mean to think with one’s ears? How does one get into the habit of it? And what are the critical and societal (ethical and political) benefits of thinking with one’s ears?

“Experiments in Listening” proposes to address these questions starting from the experimental performing arts. Conceived between an arts institute, a university, and a contrarian international journal of literature and culture, the conference seeks to “emancipate the listener” (to riff on Jacques Rancière) into considering their ears as not only aesthetic but also political instruments that are as central to how we think, make, and live as our speech.

Friday, January 24

University of Southern California

10am-12n

ROOM: USC, Taper Hall of Humanities (THH) 309K

boundary 2 editorial meeting for boundary 2 editors

Lunch for boundary 2 editors and conference speakers

*

1:30pm-3:15pm

ROOM: USC, SCA 112

Listening session/ Moderator: Erin Graff Zivin

Gabrielle Civil, “listening: in and out of place”

Fumi Okiji, “To Listen Ornamentally”

Josh Kun, “Migrant Listening”

3:30-5:30pm

ROOM: USC, SCA 112

Listening session/ Moderator: Kara Keeling

Michael Ned Holte, “Looking for Air in the Waves”

Mlondi Zondi, “Sound and Suffering”

Leah Feldman, “Azbuka Strikes Back”

Nina Eidsheim, “Pussy Listening”

6pm-7:30pm

Dinner for conference speakers — USC

8:00-10pm

ROOM: CalArts DTLA building. 1264 West 1st Street.

8pm: Reception

8:30pm: Screening of Omar Chowdhury, BAN♡ITS (17m22s, 2024) (in progress).

Out near the porous, lawless eastern border between Bangladesh and India, a diasporic artist returns to make works with a band of washed up ban♡its who are obsessed with Heath Ledger’s Joker. As they comically re-enact their glorified past, we confront the divergent histories and philosophies of peasant banditry and political resistance and its unexpected causes and contexts. The resulting para-fiction questions its authorship and morality and asks: when the art world comes calling, who are the real ban♡its?

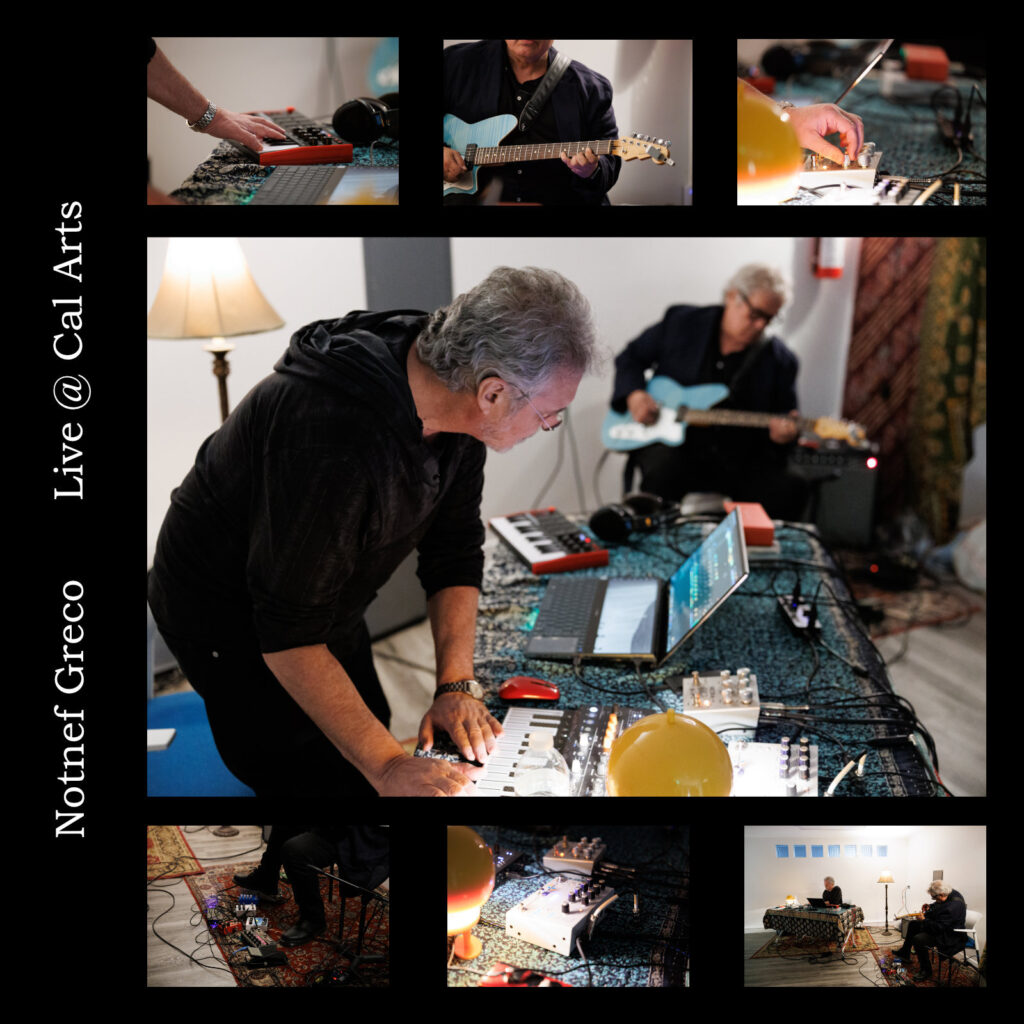

9pm: Performance by Notnef Greco (Deviant Fond and Count G).

Saturday, January 25

The REEF building (1933 South Broadway, Los Angeles, California 90007)

10-11:50am:

ROOM: Screening Room, 12th floor

Coffee and pastries.

Listening session/ Performance. Moderator: Arne De Boever

Arne De Boever, “Silent Music”

Michael Pisaro-Liu, “Experimental Music Workshop” (1 hour). Performance of Antoine Beuger, Für kurze Zeit geboren: für Spieler/ Hörer (beliebig viele)/ Born for a Short Time: For Performers/ Listeners (as many as you like) (1991).

Conference speakers will participate in the performance. Performance will be audio/video-recorded and posted at boundary 2 online. A livestream will be available here. Composer Antoine Beuger will be joining us for the Q&A after the performance via zoom.

Lunch for conference speakers–Commons, 12th floor

1:30pm-3:15pm

ROOM: Screening Room, 12th floor

Coffee and pastries.

Listening session/ Moderator: Kara Keeling

Gavin Steingo, “Whale Song Recordings”

Natalie Belisle, “Inclination: The Kinaesthesis of Afro-Latin American Sound”

Stathis Gourgouris, “The Julius Eastman – Arthur Russell Encounter”

3:30-5:15pm

ROOM: Screening Room, 12th floor

Listening session/ Moderator: Erin Graff Zivin

Edwin Hill, “On Acoustic Jurisprudence”

Bruce Robbins, “Listening On Campus”

Jonathan Leal, “If Anzaldúa Were a DJ, What Would She Spin?”

5:30-6:15pm

ROOM: Screening Room, 12th floor

Student Theory Slam/ Moderator: Arne De Boever

Reina Akkoush

Jacob Blumberg

Sean Seu

Inger Flem Soto

…

6:30pm-8pm

Dinner for conference speakers–Commons, 12th floor

8pm

ROOM: Screening Room, 12th floor

8pm: Reception

8:30pm: Tung-Hui Hu, “How to Loop Today”

Listener Biographies

Reina Akkoush is an award-winning Lebanese graphic and type designer currently pursuing an MA in Aesthetics and Politics at the California Institute of the Arts. Research interests include Middle Eastern design, Arabic typography, Marxist critical theory, cultural memory and decolonial thought in the global south.

Natalie L. Belisle is an Assistant Professor of Spanish and Comparative Literature in the Department of Latin American and Iberian Cultures at the University of Southern California, where her research and teaching focus on contemporary Caribbean and Afro-Latin American literature, cultural production, and aesthetics. Professor Belisle’s first book Caribbean Inhospitality: The Poetics of Strangers at Home will be published by Rutgers University Press in 2025.

Jacob Blumberg is an artist and producer working across the disciplines of music, film, photography, fine art, performance art, and religious art. Global in scope and local in focus, Jacob’s work as a collaborator and creator centers deep listening, voice, and play.

Arne De Boever teaches American Studies in the School of Critical Studies at the California Institute of the Arts. He is the author of seven books on contemporary fiction and philosophy, as well as numerous articles, reviews, and translations. His new book Post-Exceptionalism: Art After Political Theology was published by Edinburgh University Press in 2025.

Omar R. Chowdhury is a Bangladeshi artist and filmmaker. He creates para-fictional installations, films and performances that animate the fault lines of diasporic life and its various radical histories. He has had recent presentations and performances at Busan Biennial 2024 (South Korea), Contour Biennial 10 (Mechelen), Dhaka Art Summit, Beursschouwburg (Brussels), De Appel (Amsterdam), and screenings at International Film Festival Rotterdam, Film and Video Umbrella (London), Haus der Kulturen der Welt (Berlin), and Queensland Gallery of Modern Art (Brisbane) for Asia Pacific Triennial 8.

Gabrielle Civil is a black feminist performance artist, poet, and writer, originally from Detroit, MI. Her most recent performance memoir In & Out of Place (2024), encompasses her time living and making art in Mexico. The aim of her work is to open up space.

Nina Eidsheim is a vocalist, sound studies scholar and theorist. She brings extensive knowledge, experience and innovative approaches to practice-based research that focuses on sound and listening. The author of Sensing Sound: Singing and Listening as Vibrational Practice and The Race of Sound: Listening, Timbre, and Vocality in African American Music.

Inger Flem Soto is a doctoral student in Comparative Studies in Literature and Culture at USC. She is interested in issues of sexual difference, continental philosophy, psychoanalysis, and Latin American feminist thought. Her dissertation focuses on the mother figure in Chilean works of literature and philosophy.

Stathis Gourgouris is professor of classics, English, and comparative literature and society at Columbia University. He is the author of several books on political philosophy, aesthetics, and poetics, the most recent being Nothing Sacred (2024).

Edwin Hill is Associate Professor in the Department of French and the Department of American Studies & Ethnicity at the University of Southern California. His research lies at the African diasporic intersections of French and Francophone studies, sound and popular music studies, theories of race.

Michael Ned Holte is a writer, curator, and educator living in Los Angeles. Since 2009, he has been a member of the faculty of the Program in Art at CalArts, and he currently serves as an Associate Dean of the School of Art. He is the author of Good Listener: Meditations on Music and Pauline Oliveros (Sming Sming Books, 2024).

Tung-Hui Hu is a poet and media scholar. He is the author of three books of poetry, most recently Greenhouses, Lighthouses, which grew out of his graduate studies in film, as well as two studies of digital culture, A Prehistory of the Cloud and Digital Lethargy: Dispatches from an Age of Disconnection, an exploration of burnout, isolation, and disempowerment in the digital underclass.

Kara Keeling is Professor and Chair of Cinema and Media Studies in the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California. Keeling is author of Queer Times, Black Futures (New York University Press, 2019) and The Witch’s Flight: The Cinematic, the Black Femme, and the Image of Common Sense (Duke University Press, 2007).

Josh Kun is a cultural historian, author, curator, and MacArthur Fellow. He is Professor and Chair in Cross-Cultural Communication in the USC Annenberg School and is the inaugural USC Vice Provost for the Arts.

Jonathan Leal (he/him) is an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Southern California. He is the author of Dreams in Double Time (Duke University Press, 2023), which received an Honorable Mention for Best Book of History, Criticism, and Culture from the Jazz Journalists Association. His next book, Wild Tongue: A Borderlands Mixtape, is under contract with Duke University Press.

Fumi Okiji is Associate Professor of Rhetoric at the University of California, Berkeley. She arrived at the academy by way of the London jazz scene and draws on sound practices to inform her writing.

Michael Pisaro-Liu is a guitarist and composer. Recordings of his music can be found on Edition Wandelweiser, erstwhile records, elsewhere music, Potlatch, another timbre, ftarri, winds measure and other labels. Pisaro-Liu is the Director of Composition and Experimental Music at CalArts.

Bruce Robbins is Old Dominion Foundation Professor in the Humanities at Columbia University. He is the author of Secular Vocations: Intellectuals, Professionalism, Culture (1993), Perpetual War: Cosmopolitanism from the Viewpoint of Violence (2012), and, most recently, Atrocity: A Literary History (2025).

Gavin Steingo is a professor in the Department of Music at Princeton University. He is working on a series of books and articles about whales, music, politics, and the environment.

Sean Koa Seu practices dramaturgy, theater direction, and production. He has credits with the National Asian American Theatre Company, Transport Group, and Lincoln Center Theater. He produced the short documentary The Victorias, which was acquired by The New Yorker in 2022.

Erin Graff Zivin is Professor of Spanish and Portuguese and Comparative Literature at the University of Southern California, where she is Director of the USC Dornsife Experimental Humanities Lab. She is the author of three books—Anarchaeologies: Reading as Misreading (Fordham UP, 2020), Figurative Inquisitions: Conversion, Torture, and Truth in the Luso-Hispanic Atlantic (Northwestern UP, 2014), and The Wandering Signifier: Rhetoric of Jewishness in the Latin American Imaginary (Duke UP, 2008)—and is completing a fourth book entitled “Transmedial Exposure.”

Mlondi Zondi (they/he) is an assistant professor of comparative literature at the University of Southern California. In addition to scholarly research, he/they also work in performance and dramaturgy. Mlondi’s writing is forthcoming or has been published in TDR: The Drama Review, ASAP Journal, Liquid Blackness, Contemporary Literature, Text and Performance Quarterly, Mortality, Canadian Journal of African Studies, Safundi, Performance Philosophy, Espace Art Actuel, and Propter Nos.

-

2022 boundary 2 Annual Conference-50th Anniversary Meeting Videos Available Now

The 2022 boundary 2 Annual Conference was held from March 31-April 2 at Dartmouth College. The meeting also celebrated the 50th anniversary of the journal. Talks from the conference are now available online below and via YouTube.

Paul A. Bové: The Education of Henry Adams

Charles Bernstein: Reading from his Poetry

Arne DeBoever: Smears

David Golumbia: Cyberlibertarianism

Bruce Robbins: There Is No Why

Christian Thorne: “What We Once Hoped of Critique”

Jonathan Arac: William Empson and the Invention of Modern Literary Study

Stathis Gourgouris: No More Artificial Anthropisms

Donald E. Pease: Settler Liberalism

Lindsay Waters: Still Enmired in the Age of Incommensurability

R.A. Judy: Poetic Socialities and Aesthetic Anarchy

Hortense Spillers: Closing Remarks

-

Rob Wilson, Stubborn Resistance: Juliana Spahr’s Auto-ethnography in the U.S. Poetic Undercommons

by Rob Wilson

a review of Julianna Spahr’s DuBois’s Telegram (Harvard University Press, 2018)

He called his doctor and joked to him that he was ill with late capitalism. His doctor did not laugh…

–Juliana Spahr and David Buuck, “The Side Effect,” An Army of Lovers.[1]

Change is quick but revolution

will take a while.

America has not even begun as yet.

–Diane di Prima, “Revolutionary Letter # 10”[2]

Amid atrophied hopes for a literature effectively ‘revolutionary’ in a precarious time of post-Occupy, authoritarian revanchism, the far-flung ills and blockages of Late Capitalism, and what she tracks as returns of “stubborn nationalism,” Juliana Spahr stakes her claim for U.S. poetry with a bleakly Adorno-esque refusal she aims to conjure into new millennial credibility: “’this is not a time for political works of art.’”[3] The three postwar U.S. literary movements she tracks in Du Bois’s Telegram: Literary Resistance and State Containment – turn-of-the-new-century alter Englishes, avant-garde modernism, and movement literatures of resistance since the mid-1960s– will offer an emplotted “slide from [Audré] Lorde to Adorno” (15). This means the shift from claims of poetic activism in writing as such, back to negation, irony, or qualification of such immediate claims for transformative resistance. All this movement is figured under the pervasiveness of capitalist structures and presumes what Spahr calls literature’s semi-autonomous or “half-in and half-out relationship with capitalism” (16) and so many varied refusals of “complicit nationalism” (53). To phrase this in the book’s overall analytical trajectory, Spahr tracks how “movement literature with its ties to militant resistance [across the late 60s and early 70s] morphed into multicultural literature” across later decades that instead seek to represent national inclusion and canonical assimilation of diversity (127).

Spahr’s much-needed lyric/critical jeremiad, putting the micro-literary (poetics) and the macro-political (structured relations) together where they belong, tracks an under-recognized trajectory of state interference in literary figurations and more sublimated avowals into the turn of the twenty-first century as immersive poet-scholar subject. Spahr complicates and renews “the vexed and uneven relationship between literature and politics,” challenging the all too literary avowal that “literature has a role to play in the political sphere, that it can provoke and resist” (4); that writing (especially “language writing”) as such comprises a politics of resistance in its negations, fragments, non-linearity, and deconstructions. Framing structural issues and social relations between literature and the state as well as alternative forms of what literature might do politically, Spahr deepens the grasp between such historical ties and private foundations, sites of higher education, as well as publishing outlets both multinational and “a localized, decentralized small press culture” (5) in localities like Honolulu, Oakland and Buffalo. The book is ‘auto-ethnographic” of Spahr’s own entanglements, complicities, and refusals of American literary-national culture and its university programs and funding structures that sustain it short of revolution and resistance as nourished in the coalitional social “undercommons.”[4]

Writing on the side of alternative languages and social forms, language becoming minor and de-Anglicized, Spahr embraces the micropolitical flux of what M. M. Bakhtin called the “heteroglossia” within the dialogics of the sign.[5] She yet warns that “there is no robust counter” as alternative to state funding forms and modes of liberal domination, “with a politics that is anything more contestatory than liberal” (26). Her heart, as poet, editor, publisher, and teacher, remains tied to alternative production and circulation sites in communities of resistance from subpress collective in Honolulu and Chain in Philadelphia to Commune Editions in Oakland. Even as she elaborates multiple forms (experimental, multicultural, neo-formal modernist or worse) for containing, manipulating, acculturating, and restricting “literary resistance” by the American state, still somehow, this study remains hopeful of “antistate” (53) as well as “other-than-national” (53) poetics in form, substance, and social relation.

This is no melancholic rear-view mirror, but a proleptic movement forward as such into and beyond the contemporary. The sustained argument or, better said, way of reading this poetry is finely scaled at critical-creative levels of macro and micro intervention that may just carry the new millennial day (“it survives”), even if as W. H. Auden demurred in the radical thirties of Yeats, Eliot, Pound, and Rukeyser,

For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its making where executives</p

From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs,

Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives,

A way of happening, a mouth.[6]

Making unexpected linkages from Paris and NYC to Africa and the Pacific, Spahr’s study shows that American liberal-literary culture (not just amid well-studied Cold War antagonisms and cooptation but into the blockages of the present moment), was never that free or autonomous. It was never under-determined or “apolitical” in poetry’s homespun global diplomatic role to shape the world into an American telos figured as freedom, liberation, and self-determination, especially in the global wake of World War II and rise of English.

“Relentless monitoring” and co-optation of literary sites, outlets, and works became the US state-funded norm to counter, mollify, moderate, neutralize, and defuse resistance and thus keep any form of “armed militancy” (especially black or Third-World affiliated) at foreign bay (130-131). Networks of foundation funding and State Department support provided the capillary flow of power and capital, covertly and more openly so at times across the sixties and seventies if still “under recognized” (141) in its pervasive impact and consequences as Spahr claims. At the university level, this meant “an institutionalization of these culturalist movements that would sever them from more insurgent and militant possibilities as they were located within the university” (139). Such networks of biopower helped to produce and contain racialized resistance, as Roderick Ferguson, Eric Bennett, and Jodi Melamed et al have noted, as recuperated within if not beyond the Cold War academy.[7]