by Anna Kornbluh

This essay was peer-reviewed by the editorial board of b2o: an online journal.

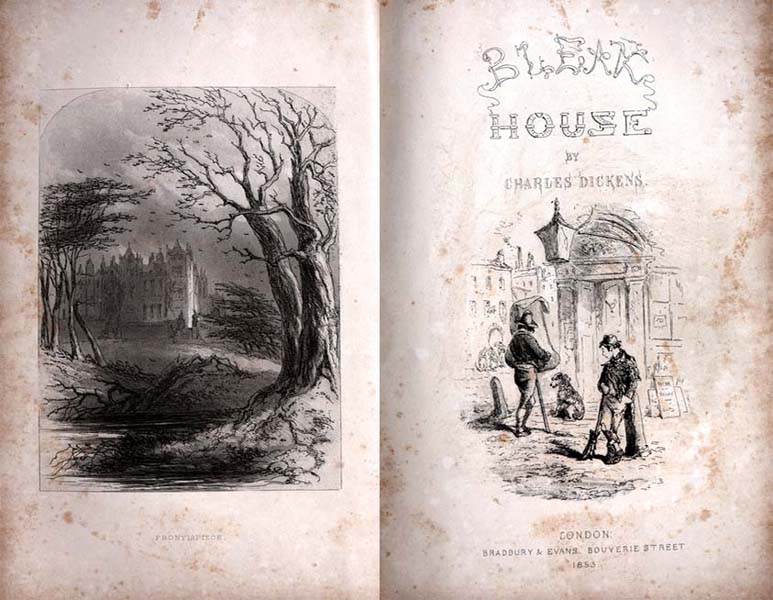

Between two novels, a thought. A thought they each think, but a thought whose thinking appears more forceful by the shade of their juxtaposition. Reading for this contiguity necessitates looking awry at the obvious distance between the two: one 2005, the other 1853. Two novels, one hundred and fifty-two years apart, nonetheless conceptually close; historically divergent but intellectually congruent. Both routinely heralded by critics as emblematic of paths for the novel form, high social realism and avant-garde experimentalism. Both in their own right institutions in the history of the novel, and both demonstrably novels of institutions.[1] Both unfold along central axes of settlements to cases of grave legal and financial complexity. Both drive their action with architectural repetition, assembling a succession of spaces that double or foil one another, and climaxing in the construction of architectural replicas. Both systematically perform and probe copying and repetition. Both take the dynamic overlaying of these topoi, the law, architecture, and repetition, as a commanding impetus for the novel form. Repeating law, repeating architecture, the architecture of the novel, the law of the novel, the architecture of the law, the law of architecture. A hypothesis: Bleak House and Remainder together novelly conceive a political formalism, a commitment to the architectural constitution of lived social space.

This is a thought whose repetition between two novels belies its novelty. Amidst today’s hegemonic vitalism – so many tomes of 20th and 21st century critical theory directed to the anatomy of governmentality and the excision of the state, law, and form itself; the practical lament of sovereignty, suspicion of organization, encomium of anarchy, ecstasy of life; the historicization of the Victorian age as the origin of the species of modern domination; the hypostasization of freedom as a messianic sublime beyond every institution, beyond every state, “beyond every idea of law”[2] – amidst and against these theoretical and practical orthodoxies of the contemporary, with Remainder and Bleak House we can think another, rarer kind of thought, a thought out of time yet all too timely. In the lavishness of their repetitive thought of law, architecture, and repetition, these novels ratify shaping, sheltering, formalizing as insuperable, indispensable, and inventable. Human is zoon politikon, the political animal, the animal whose very life is owing to the house of arbitrarily formalized collectivities; the prevalent post-political fantasies in the post-human era repress this material fact and suppress practices and theories that might build entirely new kinds of houses. Affirming radically ungrounded acts of house fabrication, showcasing the artifice without which there is nothing, fathoming the instituting of a minimal socius as a process both legal and architectural, plumbing the infrastructures of existence, opposing vitalist orthodoxy – this is the thought of Bleak House and Remainder.

It is a thought whose transtemporality or acontextuality is integral, a thought that gains gravity precisely by virtue of its repetition in history, in these two such differently situated and differently styled projects, a thought requiring repeated, apposite clauses. A thought about the enduring repetition of intricate legal negotiation as reduplicative construction of lived space, a thought not of a historical particular, not issuing from or caused by a historical situation, but of history, mediating a universal. It is a thought of the history of sociality and social formalization in modernity, a thought of the history of the novel as the art form uniquely addressed to such history. Not to say that the thought is unthought in Bleak House before Remainder, nor that Remainder merely repeats or rethinks – remainders – Bleak House (One could ask Tom McCarthy if he’s read Bleak House; I didn’t). Rather to say that what Susan Stanford Friedman has called “cultural parataxis,” the radical collage of texts from different geohistorical coordinates, can produce new textual insights and new theoretical insights (2013, 42). Knowing things in their place is obligatory, but taking things out of place might help us appreciate here how much displacement orients both of these texts: in their procedures of replicating place and of auditing the lack of an authentic place, lack of a functioning place, lack of an immanent scheme for the placing of place, both of these novels function as theories of displacement, and demand therefore to be read displacedly, out of context.

Thus, I take the fact of repetition – of recurrent tropes and recurrent combination of tropes that amount to recurrent thought – as sufficient authorization for reading these texts together, for committing a certain presentism in celebrating reverberation and hearing there a resource for contemporary theoretical debates. The repetition between Bleak House and Remainder transpires in history, but stakes no roots in that repetition Giovanni Arrighi (2010) finds in the long centuries of capital’s cycles; nor in the repetition as discontinuous intensification that Walter Benjamin (1968) finds in nonlinear philosophical, cultural, and aesthetic trajectories.[3] Let’s guess instead that the repetition is its own pattern, not governed by other patterns – simply a recurrence with neither linear cause nor intensifying arc, a recurrence of a thought, a thought that is less discursive (anecdotally characteristic of a particular society at a particular moment) and more generic (sociality as such entails the reiterative delineation of social space itself, the reiterative contrivance of formalized shelter and formalized relation, the reiterative production of worldliness which animates “the novel” art). A thought that repeats because, indeed, it is a thought of repetition, a thought of the reiterative, redoubling, reformative ungroundedness of form.

Arguing then that the repetition signals the resonance, the import, the portability of the thought across context. That what is common to the form of these two texts (where form is genre, theme, plot, and above all the engineered, dynamic collision of multiple topoi) is an illumination of common form, of the forms that structure being-in-common. This would therefore be an abstract thought, and thus a thought abstractly broaching other idioms, in contemporary work on the aesthetic caliber of politics and the political by Jacques Rancière (2006) and Caroline Levine (2015) – even as it is a thought that largely countermands the consensus in much contemporary theory, and even as it is a thought concretely enunciated by the form of the novel in each text and by the form of repetition across the two texts. Superposing tropes of displacement, replication, inauthenticity onto tropes of architecture and housing onto tropes of legal suits and legal regulations, Remainder and Bleak House highlight the aesthetic facets of social structuration: the art, the artful, the artless, the arbitrary formalizations of social relations.

An abstract thought, but one best legible in the concrete affinities between two novels. Try to take both novels as the subject of claims and sentences, to hold two novels in single (dilated, ungainly) sentences, to contrive a grammar of resonance, to suspend privileging one over the other. Both Bleak House and Remainder derive their premises from the law, from civil proceedings and settlement negotiations, from legal intricacies in process after other legal instances before them (Jarndyce & Jardynce, Dickens carefully points out, has no exact referent but extrapolates from cases regulating compound interest accumulation in estates and on cases whose contestation costs absorbed entire estates; a “remainder” is first and foremost (in the OED) a successive property interest, possessable only when prior interests granted simultaneously end, as in “die”). Both begin in medias res (in Bleak House the case has been on for decades and “has in the course of time become so complicated that no man alive knows what it means”; in Remainder the offer of a settlement for a never specified matter begins the action on the very first page and the dispensing of funds fuels the events in the narrative). Both also begin in a present tense that heralds its own limits: “About the accident itself I can say very little.” “I have a great deal of difficulty in beginning to write my portion of these pages, for I know I am not clever.” “London.” Present tense, ongoing verbs, first person split from itself, single-word sentence, dual-beginning, incapacity to narrate at the inauguration of the narration. Both refuse any standard plotting around their central legal conceits: there is no origin of the legal story (in Bleak House no flashback to the legator’s intent nor rival versions of the will; in Remainder no account of the accident prompting, nor parties to, the settlement), and there is no resolution of the legal story (in Bleak House the estate consumes itself in court costs, rendering irrelevant the determinations of who the true beneficiaries are; in Remainder the settlement funds may or may not be consuming themselves in risky investments and the narrator may or may not have worse injuries than the settlement covers). Both novels further refuse resolution at the concluding moment of their final sentences, the 1st Person narrator of Bleak House notoriously ending the 1000 page novel with a sentence fragment (“even supposing…”), and the narrator of Remainder ending his adventures at their height, in an airplane he has hijacked, up in the air, flying in loops, with neither plan nor indefinite fuel (“just keep on. The same pattern…the weightlessness set in once more as we banked, turning, heading back, again.”) Both novels conduce to end where they begin, “closing the loop, so to speak” (R, 4): Remainder’s narrator makes loops in a plane in the sky in his final phrases, loops from which the third sentence opening the book might follow (“It involved something falling from the sky. Technology. Parts, bits. That’s it really.”) – the narrator chronically tastes and smells cordite, a substance used in ejector seats from planes -; while Esther is restored to her origins and installed at the replica Bleak House. Both novels emphatically underscore copying – technologies of copying, from handwriting to mimicry to cinema to reconstruction, and ontologies of copying, from missing originals and obscured origins to imprecise rendering and unreliable narration.

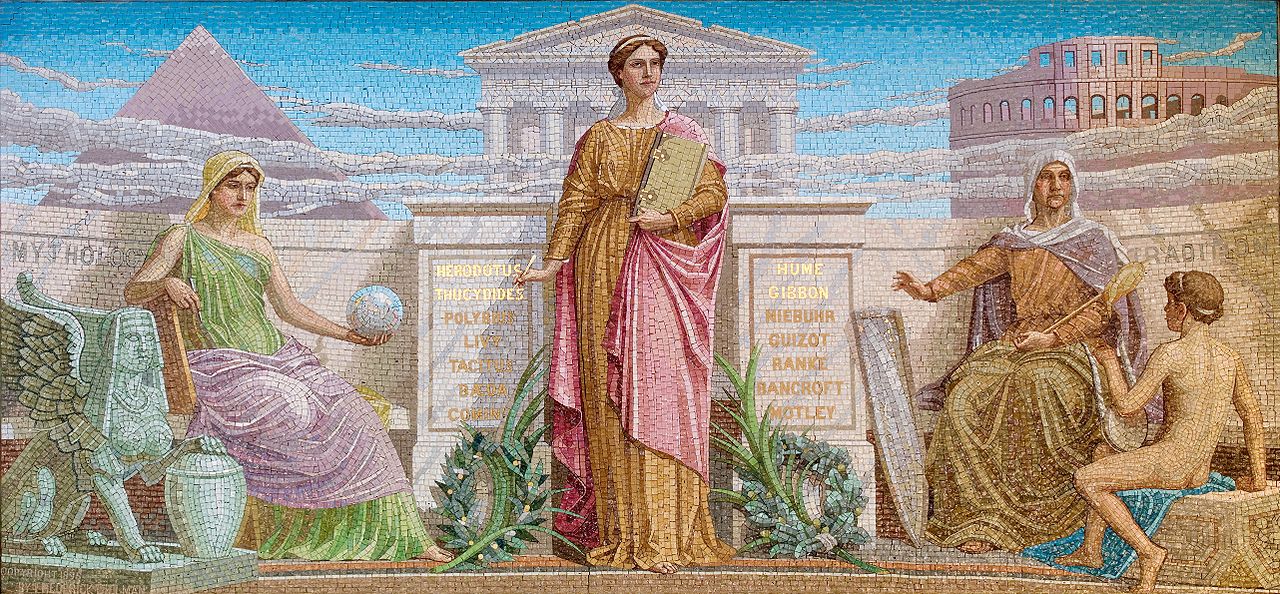

Between the two novels, and common to the two novels, is a certain shared thought about the structuring force of the law accompanied by the irrelevant content of the law: law is premise, law is impetus, law is tautology, law is originless, law is repetitive; law is not plot. Legal absolutism: there are settlements, there are cases, the law is the origin of all plots – even as there is also a profound indifference to the law’s particulars. In the repetition between the two novels, such absolutism appears much less as judgments of laws in their particular instance and context and more more as meditations on the universal character of law as organizing form. Such transtemporality is also formally inscribed in both novels’ refusal of resolution, refusal of origin, ongoingness, concluding gerunds: a persistence, a perdurance, a transcendence of this character of the law. Bleak House and Remainder are projects in world-making that both fundamentally exalt manifold constructions and manifold replications, and grant the groundlessness of any construction.

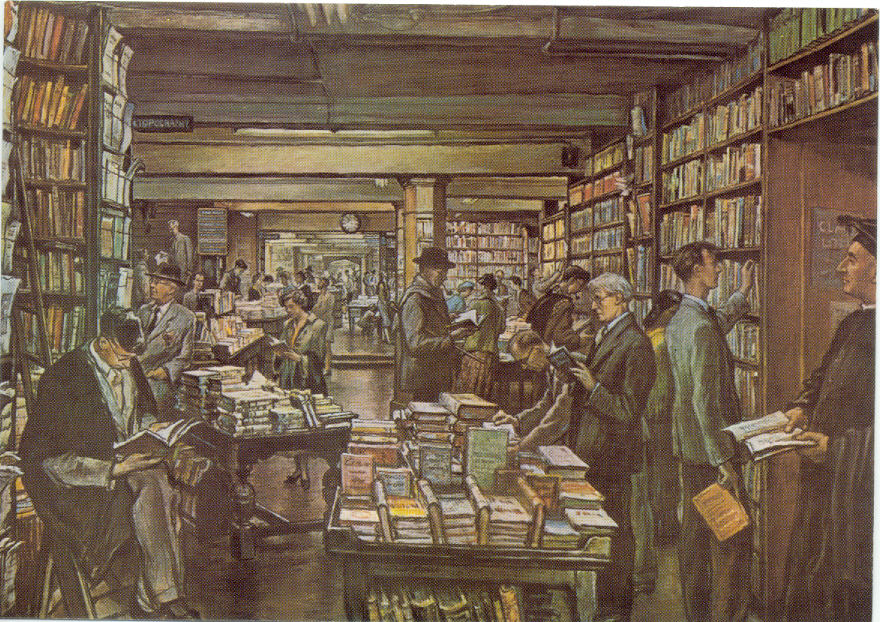

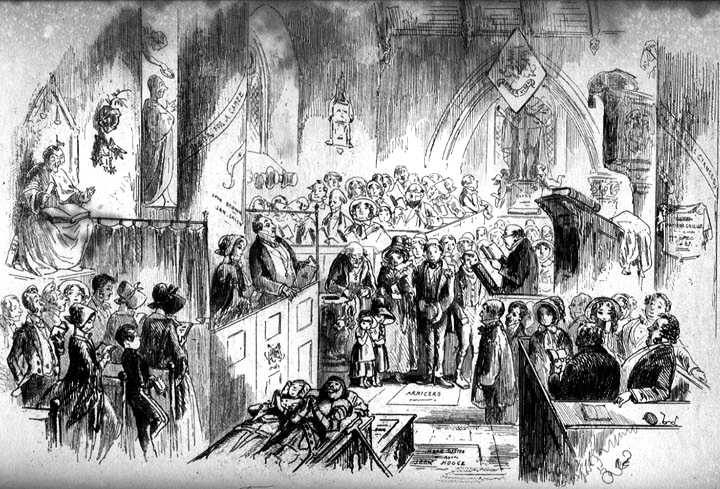

Both Remainder and Bleak House mobilize these formalist reflections on the law in the context of their manifest absorption with architecture and architectural repetition. Bleak House, to state the obvious, is about a house, about the house, once “The Peaks,” then “Bleak” (dark), then “Bleak” (light), replicated in London, and replicated in New Bleak House, about houses of law, of aristocracy, of debt, of orphans (Chancery, Chesney Wold, Coavinses, Krook’s, boarding), about houses as buildings, dwellings, shelters, about clusters of buildings (Tom All Alone’s), about contradictions at the heart of houses, about the insufficiency and ill-fabrication of every house, and, for an ostensibly urban novel, its action markedly takes the form of procession through a series of houses (take just one strata of this about-ness: when Esther learns of her mother’s identity from Lady Dedlock, her narrative dispatches with the climactic dialogue in two paragraphs of retrospective summary, but then immediately lingers for pages of description of Chesney Wold, a better evocation of her “place” than any personal melodrama; the preferred mode of characterization throughout is to describe a character’s house). Remainder is about a crack, a wall, a bathroom, a building, a courtyard, a cluster of buildings, a space and the protagonist’s drive to effect the space’s meticulous, minute (re)construction, about plaster, wood, glass, about the pursuit of a nonexistent original, about finance, coordination, about the large scale industry of building and “reenacting” a milieu, about construction work repetitively undertaken, workers humming “History Repeating.” Both novels foreground the labor of all this repetitive constitutive construction, especially in figures of clerks (Nemo the law copier, Snagsby the stationer, Guppy the uppity clerk, Krook the document collector, Tulkinghorn the portmanteau pilferer, and the countless clerks in Chancery are resounded in Remainder’s Nazrul Vyas the TimeControl™ “facilitator,” from “a long line of scribes, recorders, clerks” (77), Annie the submanager/designer, and the countless subcontractors they coordinate). The law and architecture, repeated, and the labor and craft and writing of repeating them. Repetition of the law, repetition of architecture, repeated. In the lamination of law and architecture, of inscription, institution, repetition, and the built form, both of these novels give us to think the structuration of social space.

In their manifold affinities, these two novels of course manifestly differ, but formulate the difference in terms other than context: each text uniquely approaches its cast, the marriage plot, multiplotting, mystery, money, empire, perpetuity. For the sake of brevity, focus on the most crucial difference: systematicity. Bleak House effectuates the repetitive assembly of houses as its objective core (the novel studies the ways of the world, the repeated instituting of social space, the manifold failures that drive these repetitions), whereas Remainder expressly subjectivizes this project (the novel presents itself as the study of one man’s drive). Remainder fittingly enacts this subjectivism in its narration, a 1st person narrator eschewing any reliability pretensions; Bleak House objectifies unreliability in the split between its 1st and 3rd person, not only by alternating chunks of chapters and differentiating tenses, but by lapsing each narrative mode into the purview of the other, frequently styling Esther as an omniscient observer and frequently styling the 3rd person as a partial, 1st person plural. Bleak House, one might say, is more systematic in its political purview, percussing the dynamics of social formalization more widely (in different kinds of institutions, in different kinds of people, in different registers of consciousness), while Remainder hones the narrow point of political ontology, the remaining fundament that ligates life to social forms. This difference has little to do with the nineteenth century novel’s reputed referentiality and representational naiveté, little to do with the twenty-first century novel’s reputed robust irony, and much to do with varieties of repetition: Bleak House repeats its insights at scale, contemplating “the whole framework of society,” while Remainder thematizes repetition with centripetal force.

Remainder perhaps appears then as a minimalist, bleaker Bleak House, an attenuated vastness, distillate of a gurgling solution. It zeroes in on money as predominant institution, it takes replication without referent as its single plot, it individualizes and delimits world-building, since the replicas originate in personal trauma and drive towards larger-scale violent destruction, and since it seemingly dispenses with the very possibility of 3rd person narrativity. But if it is thus a kind of crystallization of Bleak House, Remainder also thereby refracts Bleak House’s own limits: the novel we are so accustomed to lauding above all for its largeness, is in so many ways, a small novel, a novel devoted to limning the limits of novel worlds and of worlds outside. From its principles of spatial contiguity to its admonition against telescopic philanthropy to Esther’s self-deprecation to its oscillating, mutually delimiting narration, Bleak House enshrines limits even while it criticizes the limits of institutions. Each of these novels function with different syntaxes for the same questions about limits as enabling constraints, about the very installation of the law as a necessary outlining of sociality.[4]

If Remainder punctuates Bleak House’s own punctual, liminal, aesthetic contemplation of limits, they share most intimately a project to deploy the form of the novel as a laboratory for constructing forms of social space, for world-making, building possible and foreign worlds, rather than recording this world. Dickens (1854) professed of his craft that he had “systematically tried to turn fiction to the good account of showing the preventable wretchedness and misery in which the mass of the people dwell”; McCarthy (2011) hypothesizes that “literature can be understood as a process of producing space, and spaces, whether they be urban or domestic spaces, or political spaces, or metaphysical spaces.” The fictive production of social space, in accordance with limits –finitude and mortality, available materials, temporal linearity and corporeal indivisibility, structural integrity – this is a plausible definition of one abiding modality of the novel (the modality we could call, in want of distinction from its foremost antipode, science fiction, “realist”).[5] Both of these novels achieve less an instantiation of this modality than a theory of it, Bleak House in so robustly underlining the limits to its own breathtaking breadth; Remainder in framing meticulous replication as an utterly fictive enterprise, and both novels reifying nothing other than the inauthenticity of reality.

A long tradition finds in Bleak House an archive of pernicious totalizations about which the novel can, at least, cheer, and, at most, despair, and a shorter tradition finds in Remainder a Nietzschean indictment of the inauthenticity of all things. But the sheer fact that both of these novels build themselves out of repeated scenes of repetitive constitution of social spaces invites us, as readers of the history of the novel genre and as readers of a contemporary present over-determined by the poles of lamentation and resignation, to behold another thought, resurgent in Rancière and Levine’s theorizations of redistributions of the sensible and repetitive enactments of forms: the made world is only made and can therefore be remade, though no building project will not repeat the ungroundedness of every social structuration. Novels in general uniquely ramify this made-ness of the world, this poetics of worldmaking; the particular novels Bleak House and Remainder actively theorize not only the artifice of any socius, but the freedoms that surprisingly inhere in political forms.

References

Agamben, Giorgio. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Arrighi, Giovanni. 2010. The Long Twentieth Century. London: Verso.

Benjamin, Walter. 1968. “Theses on the Philosophy of History” Illuminations New York: Schocken Books.

Brennan, Tim. 2007. Wars of Position. New York: Columbia University Press.

Dean, Jodi. 2009. Democracy and Other Neoliberal Fantasies, Durham: Duke University Press.

Derrida, Jacques. 1992. “This Strange Institution Called Literature,” Acts of Literature. London: Routledge.

Dickens, Charles. 1854. “To Working Men” Household Words 7 October.

Hensley, Nathan. 2012. “Allegories of the Contemporary” Novel 45:2.

Kornbluh, Anna. 2015. “The Realist Blueprint,” Henry James Review 36.

Levine, Caroline. 2015. Forms. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

McCarthy, Tom. 2011. “Interview with Tom McCarthy” The White Review 1. http://www.thewhitereview.org/interviews/interview-with-tom-mccarthy-2/

McNulty, Tracy. 2014. Wrestling with the Angel: Experiments in Symbolic Life. New York: Columbia University Press.

Ranciere, Jacques. 2006. The Politics of Aesthetics London: Bloomsbury.

–––. 2010. Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. London: Bloomsbury.

Stanford Friedman, Susan. 2013. Comparison: Theories, Approaches, Uses. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Notes

[1] I mean this claim with respect to critical reception, and to these novels’ manifest interest in organizations and constructions, but I also mean it more pointedly in Jacques Derrida’s (1992, 72) sense of a literature of institution, “which consists in…producing discursive forms, works and event sin which the very possibility of a fundamental constitution is at least fictionally contested, threatened, deconstructed, presented in its very precariousness.”

[2] Agamben (1998, 59) belongs to an arc along which I would also situate not only Foucault and Judith Butler, but also Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, and “the new materialisms.” For helpful overviews of aspects of these trends in critical theory, see Brennan (2007) Dean (2009).

[3] Hensley (2012) makes robust use of Arrighi in an essay making similar transtemporal comparison that I found inspirational here.

[4] For the Jewish and psychoanalytic origins of this concept of law as enabling constraint, in contrast to a prevailing Pauline view of law as tyrannical letter, see McNulty (2014).

[5] I argue elsewhere (Kornbluh 2015) for this understanding of realism, rooted in its affinities with architecture, but that is only a different repetition of the thought between Bleak House and Remainder. Also note McCarthy’s (2011) insistence that “realism is a construction…it’s about the constructedness of the natural and how everything that we take to be natural is in fact artificial. Nineteenth-century realists knew what they were doing was a convention. To lose sight of that is catastrophic. It’s crazy.”

CONTRIBUTOR’S NOTE

Anna Kornbluh is Associate Professor of English at the University of Illinois, Chicago. She is the author of Realizing Capital: Financial and Psychic Economies in Victorian Form (Fordham UP, 2014) and is currently completing a manuscript The Order of Forms: Realism, Formalism, and Social Space.