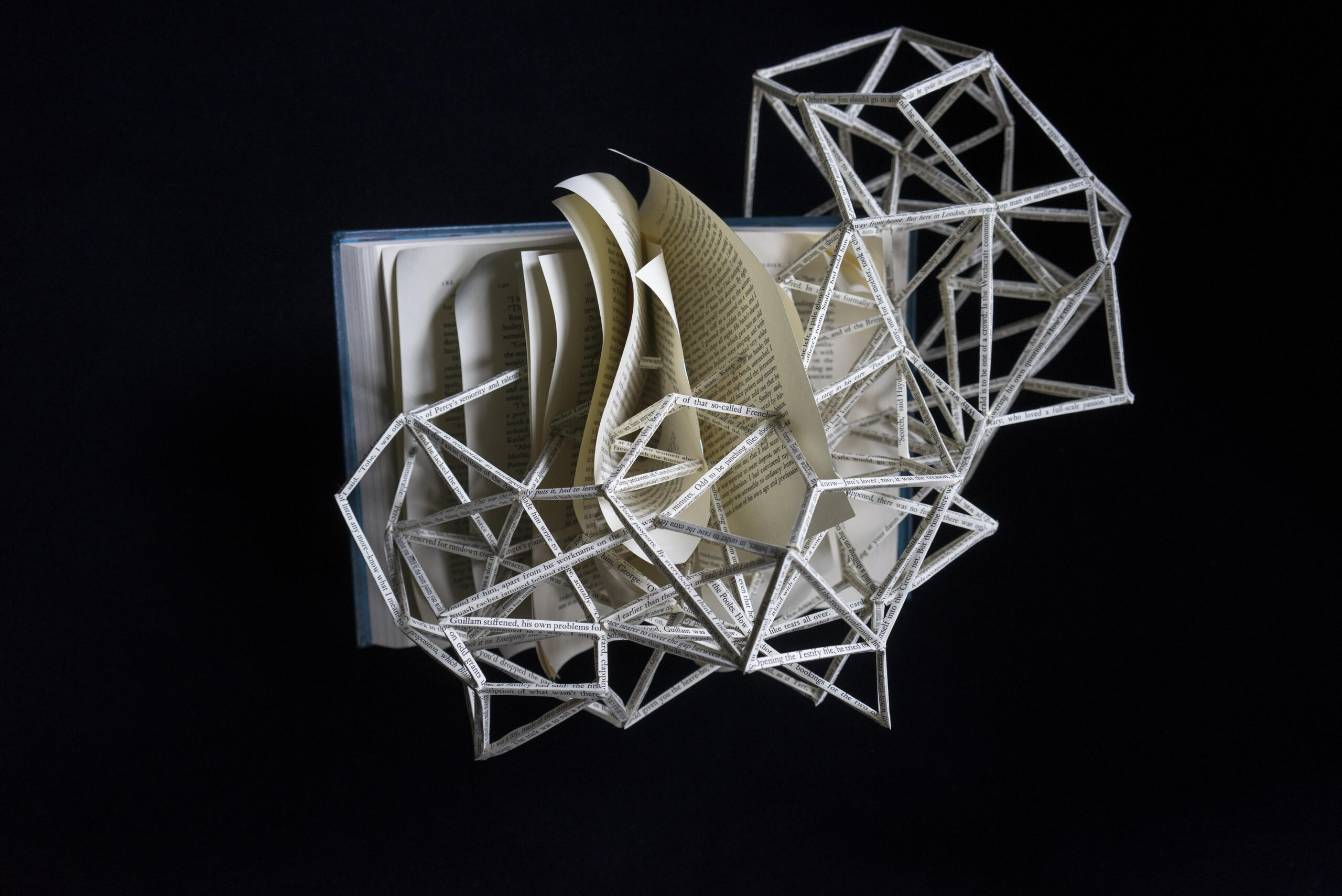

Stephen Doyle, “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (John Le Carré)”; courtesy of the artist.

This article is part of the b2o: an online journal special issue “The Question of Literary Value”, edited by Alexander Dunst and Pieter Vermeulen.

Literary Value Rests on Form

Antje Kley

This essay examines each of the terms of its title claim in an attempt to contribute to the current discussion of both the value of literature in a multimedia age, and of the authority that literature may be attributed in, for instance, interdisciplinary work.

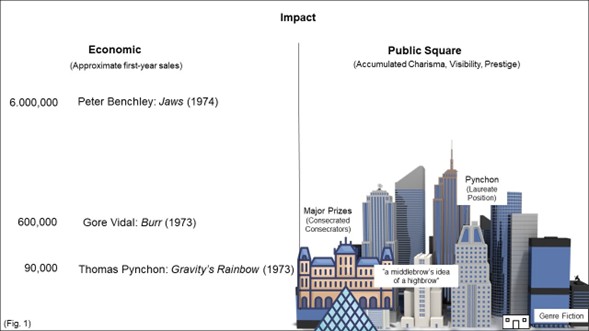

Laying out the field of literary valuation, Pieter Vermeulen (2023) draws a distinction between two current types of value assessment in literary studies, the accounts of which he finds either sociologically reductive or unduly detached from literature’s market context.[1] Vermeulen argues that the first type is interested in the instrumental relation between literature and the market: work by such authors as Dan Sinykin, Mark McGurl, Alexander Manshel, and Jeremy Rosen “tends to cast claims to literary value as strategic efforts to occupy particular market niches—most notably the niche of ‘Lit Fic’” (1232). The second type of value assessment—presented in Vermeulen’s account by Rita Felski—is interested in literature’s aesthetic uses. To avoid the shortcomings of both, Vermeulen draws on recent sociological work in the wake of Bourdieu—by Luc Boltanski, Natalie Heinich, and Michèle Lamont—that develops a pragmatics of valuation dedicated to accounting for “how value is generated and articulated in concrete interactions” (1233).

My own take on value and authority is interested in the literary textures or materialities that invite or justify valuation rather than in the grammar of public valuation in specific instances. Vermeulen might therefore group my argument along with Felski’s, but both our concerns ultimately grapple with that unequal field of tension between the market and aesthetics.[1]

Literary value rests on form. It sometimes seems that, in a capitalist world, value cannot be thought outside of economic market logics (Herrnstein Smith 1995, 178; Vermeulen 2023, 1232). In the interest of developing a critical perspective, it also seems vital, at the same time, not to surrender to those logics altogether and to continue articulating other types of value that matter to us. Therefore, I propose to heuristically tone down the noise of the literary market and its value ascriptions in order to focus on the affordances of literary textuality in comparison to other forms of text such as legal, political, scholarly, scientific, or journalistic writing. For now, I’m less interested in how one literary text is valued over others, but primarily in the basis on which texts within the uneven and dynamic field of publishing are recognized and valued as literary in contradistinction to nonliterary types of text. What, in other words, does literary writing—as opposed to legal writing or journalism—have to offer to socially situated reading subjects within the context of variously mediatized ecologies of attention and knowledge?

My claim is that any writing presented as literary invites diverse types of vicarious aesthetic experience by its construction of imaginary worlds, and by temporarily allowing reading subjects some degree of distance from their specific social contexts. The effects of aesthetic experience in immersive or close-reading processes are hard to pin down. Scholars who take aesthetic experience seriously rather than dismissing it as frivolous or pointless have variously described it as relaxing, reassuring, refreshing, emotionally intense, activating, informative, intellectually invigorating, or in some other way expansive. Through the reading subject and their contexts of reception, the affordances of literary textuality connect different types of worlds: imaginary models and empirical realities. In this respect, literature is ill-described as an autonomous realm that exists unfettered from economics, politics, and the cares of the rest of the world.[4] In contradistinction to such claims to aesthetic autonomy—and against the charge of attempting to de-commodify a clearly commercial product (Vermeulen 2023, 1232)—, I acknowledge both the inevitably social and economic nature of any kind of writing and the social and institutional framing of processes of evaluation. At the same time, culturally heterogenous versions of literary writing are de-pragmatized in ways that journalistic writing, scholarship, legal writing, and political argument are not. De-pragmatized uses of language—i.e. language uses uncoupled from field-specific functional strictures—may result in an imaginative but hardly an economic “otherworldliness”, nor in a “blissfully de-commodified celebration of the uses of literature” (Vermeulen 2023, 1232).

So, I seek to elucidate the value of literary forms of language use that, in the process of functional social differentiation, have come loose from direct instrumental or pragmatic ties—which is not the same as becoming autonomous in the sense of ‘art for art’s sake’. Instrumental or pragmatic ties put systematic constraints on the play of language in such fields as journalism, theoretical and empirical research, politics, or the law. In contradistinction to these latter fields, the field of literature enjoys the capacity and freedom to project ideas in explicitly imaginative ways: speculation, satirical or ironic distortion, the fantastic, genre patterns, incompatible perspectives, artifice, self-referentiality and metafiction have their proper place here.

Roland Barthes elaborates this distinction between different social fields’ textual production and their respective relation to language in his essay “From Science to Literature” (1989). He compares non-pragmatic literary discourse to linguistically much more constrained discourses, using as an example the empirical sciences. While scientific and literary discourse are both constituted in language, he argues, they “do not assume—do not profess—the language which constitutes them in the same way” (4). In scientific discourse, language is used as a transparent instrument subservient to scientific “operations, hypotheses, and results” (4; see also Daston and Galison 2010); for literature, in contrast, language is its condition of existence. Barthes’ claim can be said to pertain to heterogeneous manifestations of the literary, from the literary classic to genre fiction, experimental poetry to aphorism, from realist and experimentalist drama to street and post-dramatic theater. Arguably, in the multimedia age, manifestations of the literary in different media still offer the one arena in which the exploration of the materiality, the inherent logic, and the powers of language has its place—along with the practice of “prolonging [or recalibrating] our attention” (Guillory 2025, 83) in the process of reading or listening.

I share Barthes’ appreciation for the literary exploration of language in its explicit and contextualized production of truth claims. According to his argument, literary writing’s existence in and playful exploration of language throw into sharp relief the construction of objective truth that, in the empirical sciences, for instance, passes innocently through seemingly neutral registers of language.[5] Along these lines, Ansgar and Vera Nünning speak of literature, and in particular narrative fiction, as self-reflexive “world-building institutions” which serve to test what is involved in processes of worldmaking, self-making, community-building, and truth-claiming (2010, 12–16). Revealing truth as a discursive product does not devalue it but shows its dependence on contextualized construction and defense. Literary language has the capacity to flesh out the ethical and political implications of this epistemological assumption.

As Barthes argues:

Ethically, it is solely by the passage through language that literature pursues the disturbance of the essential concepts of our culture, “reality” chief among them. Politically, it is by professing (and illustrating) that no language is innocent, … that literature is revolutionary. (5)

Affirming Barthes’ structuralist take on the ethical and political value and function of literary language, I see those functions at work in literary writing as it transports readers to fictional worlds. This transport, enabled by de-pragmatized forms of language use, produces a distinct gap between the reality that shapes readers’ lives and a different world that provides fictional vantage points from which to assess the realities that readers believe they know.

I am using the term ‘gap’ here in a different way than Wolfgang Iser does in his reception theory. Whereas Iser (1974) refers to semantic gaps within texts—formal features that call for imaginative bridging by the reader—, I refer to an epistemological gap. Produced through form, this is a gap between a fictional world and the reader’s experiential world: an extra-textual gap which calls on the reader to relate the two worlds. That gap between real and imaginary worlds may, depending on the use of form, assume various qualities, sizes, and dimensions. Literary form might push that gap into the foreground, exhibit and reflect its qualities. Or it might make the gap slight and hide it behind the suggestion of mimesis. Alternatively, form might work towards giving the gap changing shapes within a single text. The literary ‘suspension of disbelief’ and the affective and/or intellectual involvement or immersion this suspension elicits may serve to question, expand, renegotiate, or transform established archives of knowledge, experience, norms, and values. The reader’s multisensory involvement may also provide comfort, reaffirmation and closure. Imaginative fictional worlds and the gaps they produce in relation to readers’ lived realities might delight, provide “critical solace” (James 2016; 2019), temporary respite, escape, or an intellectual endeavor—some type of pleasurable, vicarious aesthetic experience that opens new vistas of an unknown provenance. Through play, irony, fantasy, contradiction, exaggeration, temporal or spatial distance, literary texts open up alternative forms of understanding inner and outer worlds.

According to Sacvan Bercovitch, the function of such displaced literary doublings of the world is “to challenge our knowledge of [the world out there] in ways that return us more concretely, with more searching cultural specificity, to our nontranscendent realities” (1998, 71).[6] However, these new vistas are not in themselves benevolent or gainful, as an aggressive cultural politics from the “alternative right” makes all too clear.[7] As Ansgar and Vera Nünning remind us: “because any and every constructed world serves particular interests” it is “important to defend the plurality of worlds against the desire of homogenisation” (2010, 4). Media-generated worlds, and literary language in particular, provide space for reflection, for affective and cognitive development, as well as invitations to adopt ideas of various shades and guises. Evaluating those ideas requires contextualization and defense.

Making value judgments—i.e., the practice of distinguishing those texts that we find compelling from the ones we don’t, and explaining why—thus becomes a more explicitly normative issue. Particularly in light of a worldwide trend toward an aggressive cultural politics fueled by alternative-right populism, it is worthwhile to articulate contextualized and well-argued normative evaluations of a literary work’s ethics and politics. Michael Clune is one critic who has explicitly pursued this in his Defense of Judgment (2021). He claims that “for decades now”, professors of literature “have felt unable to defend” and have “bent over backwards to disguise” the value judgments they make (1–2). The barriers he lists to articulating artistic values—from elitism and subjectivity to narrowmindedness and irrelevance—are very recognizable (2). Clune also argues that the “resistance to judgment is historically and conceptually bound up with commercial culture” (3), so that artistic criteria have become all but elided by consumer preferences and market mechanisms (183). His claim aligns with my contention that insisting on valuation as a predominantly economic process abandons the idea that other types of value might even exist.

At the same time, Clune’s argument insists—a little recklessly, to my mind—that a commitment to artistic judgment requires giving up on a foundational concern with form in order to distill a text’s ideas:

The prospect of judging works by the quality of the ideas they contain cuts against the perennial formalism of the field, the tendency—derived from Kantian aesthetics—to turn every question about the artistic value of literature into a question of form. … [I]n practice [formalism] prevents literary scholars from constructing viable interdisciplinary methods adequate to literary content’s inevitable traversal of disciplinary boundaries. (100)

Clune demands that an artistic evaluation practice must separate content from form, that it must scrape ideas from their apparently superfluous packaging, so that they might find a larger audience who might be distressed by reflections of form. For the sake of his argument, Clune adopts a parochial sense of formalism. While briefly acknowledging that the “capacity to interpret and evaluate the formal dimensions of works is important” (106)—a strange acknowledgement, given that following his line of argument, it remains unclear why it would be—, he describes formalist reading as radically self-contained, limiting or “reducing literary value to formal criteria” (105, emphasis mine). Instead, he proposes distilling “literary ideas” (104) that would interest people beyond literary studies, separating them from reflections on form, because those “simply … don’t matter” outside of literary studies (106).

I see two major points of contention here. First, it might make sense, in specific contexts, to focus on the results rather than the process of a principled consideration of a literary text’s formal mediation of its ideas. But that does not cancel the necessity of registering the affordances of the literary text’s form. Moreover, since a literary text’s language and structure are not transparent, its ideas are hard if not impossible to separate from their formal mediation. Secondly, any concern with form goes beyond a self-sufficient enumerative identification of formal devices. In an explication of function, an account of form relates formal devices to literary historical, socio-cultural, economic and geopolitical contexts of production and reception (Levine 2015).[8]

Three brief examples may serve to indicate how literary forms afford the particular delivery of the respective texts’ content. We might, for instance, find significant interventions into and expansions on public discourse in Anna Deavere Smith’s one-woman play Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992. The script pulls passages from some 300 interviews and casts them into a series of monologues which comment on the LA riots from a variety of specifically situated perspectives. The condensation and collage of the monologues and the presentation of the various subject positions from which they are uttered by a single versatile actor draws focused and extended attention to the multilayered social and cultural concerns involved in the riots. Similarly, we might find that Claudia Rankine’s short lyric essays in her collection Citizen (2014) expand the vocabulary, syntax, and semantics of public discourse. In the aftermath of the deaths of Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, and Renisha McBride, Rankine’s adaptation of the lyric tradition (which traditionally favors interiority) minutely details the experience of racialization and allows individualized experience to resonate collectively. The integration of multi-medial visual images in the printed material and the creation of repetition, fluid transitions, and echo effects serve to focus and dilate readers’ attention to the publicly relevant implications between private experience and structural conditions. In my third example, Hernan Diaz’s historical novel Trust (2022), we might find a story of misogyny and capital’s assertion in the face of economic crisis in an experimental fourfold novel-within-a-novel. Beginning with a fictional story of a Wallstreet tycoon, followed by the tycoon’s memoir and the story of the memoir’s ghost writing, the novel ends with the diary of the tycoon’s wife. The text’s shifting perspectives and registers afforded by the fourfold narrative structure shed light on gender and class relations, the interdependencies of cultural and economic capital, the interlocking dynamics of public and private conflict, and the production of authority and truth.

Literary value rests on form. Thinking about how to articulate the connection between literary value and literary form, I settled on ‘resting on’. The phrase is somewhat nondescript. ‘Rests on’ sounds as if the connection between value and form were unproblematic and static—as if value just sits there, resting. The phrase also invites the question whether the first gust of wind will sweep value off its ‘resting place’. One reason why this special issue is launched is that we perceive the winds around the value of literature to be high. I take the connection between literary value and literary form to be a wind-resistant, even if highly adaptable one. I would call this adaptably stable connection to form constitutive of the literary. This is not the same thing as claiming that literary study is “reduc[ible]”, “restrict[ed]” or “identical to the study of form”, as Clune fears the profession insists (2021, 105, 107). Indeed, Clune’s own reading practice undermines his claims regarding the separability of form and content. While his readings do not foreground form, they generate their articulation of the text’s ideas from a consideration of form. Clune’s reading of Dickinson’s poem “I heard a Fly buzz—when I died—”, for instance, refers to lines, stanzas, aesthetic structure, tense arrangements, self-reflexivity, the speaker, voice, and perspective; it points out ambiguities and contextualizes theoretically as well as historically in order to explain the poem’s literary knowledge production about death. Literature in all its diverse guises delivers content in recourse to form. [9] Clune’s call for a non-objectifiable engagement with the literary text speaks to a lifeline between literary value and form (106–107): He suggests that readers submit their “values, concepts, and perceptions to reorganization by the work” (183). This reorganization of readers’ senses necessarily relies on the forms in which the myriad, undisciplined ideas literary writing projects, are cast.

To be clear, I share Clune’s impatience with a type of formalism that chooses to remain inattentive to the social relations which allow texts to resonate (131). His generalizing insistence that “[t]he formalism practiced by literary critics has no extraliterary significance” (2021, 104), however, is carelessly overstated (see also James 2023, 821–24). It is overstated in particular in light of his own project of strengthening outspoken evaluations of literary knowledge production which, as I have argued, rests on form in adaptable but structurally stable ways.

Literary value rests on form. I use ‘form’ as a capacious term that includes the affordances—the possible functions—that forms assume in specific historical, social, and institutional contexts of production and reception. Clearly, I am not concerned with isolated identifications of rhyme schemes or renditions of consciousness. No form is self-sufficient. Levine (2015) has clarified that forms of speaking, of material construction, and of social action are always connected to contexts of production and reception, to other forms and their functions in specific contexts (see also Funk, Huber, and Roxburgh 2019). Literary form in particular encompasses language registers and imagery; rhythm and the handling of time, space, and setting; the orchestration of voices, perspectives, and character constellations; intermedial allusion and narrative or mythical patterns, as well as genre traditions. On the basis of these devices and the suspension of disbelief they orchestrate, literary form invites reading subjects to understand projected imaginary worlds in relation to and beyond what they know—experientially, cognitively, and implicitly—about themselves and about their environments.

With Gayatri Spivak, I would contend that careful reading practices attuned to the specificities of literary language and to the variations of literary form “enhance rather than detract from the political” force of literary writing (2012, 351–52). Special attention to the specificities of literary form allows readers to read beyond (while always in the light of) what they already know. Peter Boxall explains the affordances of literary form as the twin effects of representation and critique of social realities (2015, 11). He advances his argument in reference to the novel, but I propose to expand it to literature in general to claim that literary writing “both shapes the world and resists its demands” (12). Literary form deserves attributions of value because it connects imaginary and non-transcendent realities. More specifically, literary writing sets, as Boxall writes,

the relationship between art and matter, between words and the world, into a kind of motion, to work at the disappearing threshold between the world that exists and that which does not, between the world that we already know and understand and that which we have not yet encountered. (13)

The value of imaginary worlds constructed in form thus lies in their capacity to sustain our thinking and our being by training our imagination to reach beyond what we already know (Spivak 2012, 353; Boxall 2015, 37–38).

By way of conclusion, I return to my initial question: what does specifically literary writing have to offer to socially situated reading subjects within the context of variously mediated ecologies of attention and knowledge? I have argued that specifically literary writing derives the contour and strength of its ideas from its formal mediation. It explores the shaping powers of language that are neither innocent nor transparent; it gathers, recalibrates, or prolongs readers’ attention; and it thus invites readers to suspend disbelief and transports them to imaginary vantage points. With its affordances, literary writing trains ways of looking at the world through the perspectives it provides, and it resists or accommodates the world’s demands. It exercises the muscle of readers’ imaginations to sustain their thinking and being beyond what they already know or believe they know. With its readings attentive to form, literary studies may bring this authority of the literary to interdisciplinary research contexts, enriching them with specifically literary forms of knowledge production.

References

Barthes, Roland. 1989 [1967]. “From Science to Literature”. In The Rustle of Language, translated by Richard Howard, 3–10. Oakland: University of California Press.

Baßler, Moritz, and Heinz Drügh. 2021. Gegenwartsästhetik. Konstanz: Konstanz University Press.

Bercovitch, Sacvan. 1998. “The Function of the Literary in a Time of Cultural Studies”. In ‘Culture’ and the Problem of the Disciplines, edited by John Carlos Rowe, 69–86. New York: Columbia University Press.

Boxall, Peter. 2015. The Value of the Novel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Citton, Yves. 2017. The Ecology of Attention. Translated by Barnaby Norman. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Clune, Michael W. 2021. A Defense of Judgment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Daston, Lorraine, and Peter L. Galison. 2010. Objectivity. Princeton: Zone Books.

Deavere Smith, Anna. 2003 [1994]. Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992. New York: Dramatists Play Service.

Díaz, Hernan. 2022. Trust. New York: Riverhead Books.

Emre, Merve. 2017. Paraliterary: The Making of Bad Readers in Postwar America. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Felski, Rita. 2008. Uses of Literature. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Felski, Rita. 2020. Hooked: Art and Attachment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Funk, Wolfgang, Irmtraud Huber, and Natalie Roxburgh. 2019. “What Form Knows: The Literary Text as Framework, Model, and Experiment”. Anglistik: International Journal of English Studies, 30, no. 2: 5–13.

Guillory, John. 2025. On Close Reading. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Herrnstein Smith, Barbara. 1995. “Value/Evaluation”. Critical Terms for Literary Study, 2nd ed., edited by Frank Lentricchia and Thomas McLaughlin, 177–84. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Iser, Wolfgang. 1974 [1972]. The Implied Reader: Patterns of Communication in Prose Fiction from Bunyan to Beckett. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

James, David. 2016. “Critical Solace”. New Literary History 47, no. 4: 481–504.

James, David. 2019. Discrepant Solace: Contemporary Literature and the Work of Consolation. New York: Oxford University Press.

James, David. 2023. “Exporting Expertise”. American Literary History 35, no. 2: 818–30.

Levine, Caroline. 2015. Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Leypoldt, Günter. 2026. Literature’s Social Lives: A Socio-Institutional History of Literary Value. New York: Oxford University Press.

Meretoja, Hanna, Saija Isomaa, Pirjo Lyytikäinen, and Kristina Malmio, editors. 2015. Values of Literature. Leiden: Brill Rodopi.

Nünning, Ansgar, and Vera Nünning. 2010. “Ways of Worldmaking as a Model for the Study of Culture: Theoretical Frameworks, Epistemological Underpinnings, New Horizons”. In Cultural Ways of Worldmaking: Media and Narratives, edited by Ansgar Nünning, Vera Nünning, and Birgit Neumann, 1–28. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Rankine, Claudia. 2014. Citizen: An American Lyric. Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press.

Spivak, Gayatri. 2012. An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Strick, Simon. 2021. Rechte Gefühle: Affekte und Strategien des digitalen Faschismus. Bielefeld: transcript.

Vermeulen, Pieter. 2023. “Reading for Value: Trust, Metafiction, and the Grammar of Literary Valuation”. PMLA 138, no. 5: 1231–36.

[1] Herrnstein Smith (1995) relates the distinction between a more precise notion of economic value and a broader, more elusive and abstract notion of value to the meaning dimensions inherent in “the English wordform” (178, 179).

[1] On ethnographies of evaluation in weak and strong taste cultures, see Leypoldt 2026 as well as Leypoldt’s contribution to this special issue.

[2] Yves Citton (2017) introduces the term “ecology of attention” as a challenge to “economy of attention”.

[3] See, for instance, Meretoja at al. 2015; Boxall 2015; Felski 2008; 2020; Emre 2017. John Guillory (2025) distinguishes immersive reading and close reading as two divergent practices, even though both attend to texts closely: “close reading interrupts immersive reading in order to initiate [the] rarified technique” of second-order observation in which the reader does not only observe the text, but also reflects upon their own act of observing (84).

[4] A recent structuralist attempt in that direction by Moritz Baßler and Heinz Drügh (2021) has been much discussed in German-speaking academic contexts .

[5] Daston and Galison (2010) provide a historical account of the production of scientific objectivity.

[6] See also A. Nünning and V. Nünning 2010, 6–8 and James 2019, 1–40.

[7] See Strick 2021. In his exploration of the strategic affect management on the political right, Strick argues that the right is ill-understood as the opposite of democracy but must be seen as one of its expressive forms. In order to complicate automated distancing moves, he chooses to speak not of the “far right” but of the “alternative right”, of “reflexive fascism”, and of “affect production on the right”. I here adopt his term “alternative right”.

[8] With much effort and little spirit, Clune takes apart Caroline Levine’s attempt to strengthen a much more capacious sense of form. He backs up his dismissal of formalism by tracing what he perceives to be the shortcomings of her argument (2021, 100–107). As chief among them he identifies her engagements with other discourses beyond the literary. From his perspective, using conceptual tools from other disciplines (history, sociology, political science, economics, etcetera) reduces the literary to illustrations of ideas articulated elsewhere. While I recognize that this happens, a transfer of concepts from other disciplines does not necessarily make the literary a mere illustration of empirical findings or theoretical claims. The assumption that it does relies on a correspondence theory of truth and a mimetic notion of representation that find little traction with Levine’s fundamentally constructivist take on literary writing and the act of mediatized worldmaking.

[9] On the dependence of literary value on form see also James 2019: 1–40; Spivak 2012, 354; Funk, Huber, and Roxburgh 2019.