by Sadia Abbas

by Sadia Abbas

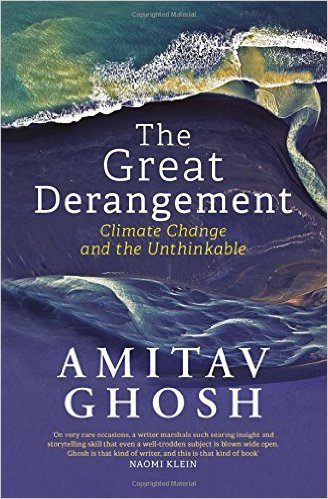

This essay has been peer-reviewed by the b2o editorial collective. It is part of a dossier of texts on Amitav Ghosh’s The Great Derangement. boundary 2 also published a conversation between J. Daniel Elam and Amitav Ghosh in March 2017.

Less than ten pages into The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, in a passage that also explains the title of the book, Amitav Ghosh summons the judgment of people from a future in which Kolkata, New York and Bangkok are uninhabitable, and the Sundarbans have been swallowed by rising seas.[1] In this time:

When readers and museum-goers turn to the art and literature of our time, will they not look first and most urgently, for traces and portents of the altered world of their inheritance? And when they fail to find them—what should they—what can they—do other than to conclude that ours was a time when most forms of art and literature were drawn into the modes of concealment that prevented people from recognizing the realities of their plight? Quite possibly, this era, which so congratulates itself on its self-awareness will come to be known as the Great Derangement (Ghosh 2017: 11).

Ghosh’s summoning of the future enables a series of dismissals of literature, which are in turn, shakily poised on shifting claims about literary fiction. The book is divided into three parts—”Stories,” “History,” “Politics”—each of which serves in different ways to address the crisis of climate change and the “great derangement” of our times. Yet, despite its division into these three parts, the rather protean claims about literature, with art thrown in, frame, drive, and are symptomatic of, many of the confusions of the book. The target keeps shifting, literature and art changes to mostly literature (art has done better it turns out), to realist literature, to literary fiction, to the gatekeepers of literary fiction.

If the book launches the attack on the failures of art and literature in our times early, it concludes with a rousing vision of their possible transformation:

The struggle for action will no doubt be difficult and hard fought, and no matter what it achieves, it is already too late to avoid some serious disruptions of the global climate. But I would like to believe that out of this struggle will be born a generation that will be able to look upon the world with clearer eyes than those that preceded it; that they will rediscover their kinship with other beings, and that this vision, at once new and ancient, will find expression in a transformed and renewed art and literature (162).

And yet, so much has been discarded along the way, so many times has the argument stumbled and contradicted itself, that this conclusion is anything but convincing.

Assuming, for a moment, that the future would care about us, enough of what we have to say and produce would survive, that anything we produce would (or should) be intelligible to those who come long after us, and that summoning such a judgment is not merely an act of historical narcissism, one might be tempted to give counter-examples: for instance, sticking with the mostly Anglophone for now, what would this putative future audience do if the art and literature that survives is (say) a fragment or two of the David Mitchell novels, Cloud Atlas and The Bone Clocks, Wilson Harris’s Guyana Quartet, Leslie Marmon Silko’s novel, Ceremony and memoir, The Turquoise Ledge, Andreas Gursky’s photographs of landfills, an online curated exhibition such as the Philippines-centered Center for Art and Thought’s Storm: A Typhoon Haiyan Recovery Project,[2] Indra Sinha’s Animal’s People, any one of a series of Mahasweta Devi short stories, Alexis Wright’s The Swan Book and Carpentaria, Shahzia Sikander’s reimagining of oil extraction machines as Christmas trees in her animation Parallax, any of the three novels in Octavia Butler’s Lilith’s Brood, Edward Kamau Brathwaite’s X/Self and China Mieville’s The Scar? As is probably evident, most of these examples are taken from Australian and American Native, Carribbean and African-American writers, many address the crisis of climate change in the context of the crisis of modernity, race, racialized gender violence, and capitalism ranging back to the sixties. My point, of course, is that writers and artists have been addressing climate change and its relation to capitalism and modernity with subtlety, care and broad visions of social transformation for a long time.

But the structure of the book is such that the argument is, in fact, impervious to counter-example—not because the broad generalizations hold true and counter-example would be trivial and miss the point, but because Ghosh alternately spins around and hollows out his claims. He gives numerous names of people who are apparently doing some sort of acceptable or even good (Barbara Kingsolver and Liz Jensen) literary work but that turns out not to be enough. Even as much is let back in in bits and pieces, the general dismissal is never withdrawn, which makes one wonder what the function of the qualifications is.[3] How many does it take to make a trace?[4]

It is around the concept of literary fiction that most of the contradictions cluster. Ghosh tells us that, when writing The Hungry Tide, he encountered the challenges presented by the “the literary forms and conventions” that gained ascendancy in the very era during which the accumulation of carbon in the atmosphere was coming to reshape the future of the earth (7). The limitations there, it turns out, were those of the realist novel. This then leads into the next section, which begins with the failures of literary fiction understood as, at least in part, failures of reception and designation by such publications as “the London Review of Books, the New York Review of Books, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and the New York Times Review of Books [sic]” where, when the subject of climate change comes up, it is usually in reference to non-fiction, where, moreover, the mention of the subject is enough to “relegate” a novel or a short story to the genre of sci-fiction (7)

This would seem like a great opportunity to question the very distinction between literary and genre fiction, to go, for instance, where Kazuo Ishiguro does—magnificently. Not only has Ishiguro written a powerful and profoundly ironic detective novel, When We Were Orphans, an eerie and haunting science-fiction novel, Never Let me Go, and a wonderful fantasy one, The Buried Giant, he has also refused to get drawn into the debate pitting genre against literary fiction, despite Ursula K. LeGuin’s accusation that he was denigrating fantasy in the service of lit-fict. loftiness, for which Le Guin subsequently apologized (LeGuin, 2015).

Ishiguro’s responses about both Never Let me Go and The Buried Giant are instructive. About Never Let Me Go: “I think genre rules should be porous, if not nonexistent. All the debate around Never Let Me Go was, ‘is it sci-fi or is it not?’”

About Le Guin’s challenge and The Buried Giant: “I think she [Le Guin] wants me to be the new Margaret Atwood…. If there is some sort of battle line being drawn for and against ogres and pixies appearing in books, I am on the side of ogres and pixies… I had no idea this was going to be such an issue.” By contrast, Ghosh writes: “It is as though in the literary imagination climate change were somehow akin to extraterrestrials or interplanetary travel” (7). Invoking the authority of Margaret Atwood, later in the book, he dismisses sci-fi and cli-fi to argue that they do not help as they deal with the future and not the present and the past.

So, of course, examples such as Butler, Mitchell, Mieville, Wright are of no use here, regardless of the fact that all of these writers provide imaginative and thoughtful literary engagements with precisely what it means to exist in the age of mass consumption and hubristic technological madness, what it means to encounter the non-human and attempt to co-exist, what it means also to confront the brutal cupidity and indifference to the planet that has brought us where we are today. Moreover, it would appear that “traces and portents,” including in—perhaps specially in—disaster stories and apocalyptic narratives, are precisely what speculative fiction/sci-fi/ cli-fi (choose your designation) offer. Why, in any case, should we assume that, even if the future is interested in the mess we bequeath (assuming that there is a human future to bequeath it to), it will share our literary prejudices?

Reducing speculative fiction, sci-fi or apocalyptic fiction merely to futures, interplanetary travel and disaster, as if those themselves have no signifying capacity beyond pure plot and event, seems to suggest that allegory, metaphor, symbol, figuration itself have no role to play. Moreover, it suggests a rather circumscribed notion of reading practices: Can a book about the future or about the past not be about the present? Really?

There is occasion here for re-thinking the history of the novel from which the gothic, ghost stories, H.G Wells somehow fall off in the twentieth-century. In other words, it’s an opportunity to argue that literary fiction—especially as defined by Ghosh and as practiced in the U.S.—is too truncated and accepts a profoundly evacuated genealogy. Ghosh does this perhaps most successfully in his critique of John Updike’s dismissal of Abdelrahman Munif’s Cities of Salt, picking up on an argument he first made in his seminal essay, “Petrofiction,” which is frequently referred to in works in the environmental humanities. Yet again, however, the attempted account of the history of literature gets bogged down in claims about science fiction, as we’ll see a little later.

There is much at stake in Ghosh’s argument. The transformation of literature he imagines is merely a part of the larger need for the transformation of society as a whole, including the rethinking of modernity, for which many have been calling for a long time. One iteration of this in the environmental humanities is presented in Ursula Heise’s description of her thesis for Imagining Extinction: The Cultural Meanings of Endangered Species:

however much individual environmentalists may be motivated by a selfless devotion to the well-being of non-human species, however much individual conservation scientists may be driven by an eagerness to expand our knowledge and understanding of the species with whom we co-habit the planet, their engagements with these species gain socio-cultural traction to the extent that they become part of the stories that human communities tell about themselves: stories about their origins, their development, their identity, and their future horizons (Heise 2010: 5).

Some of the challenges that Ghosh addresses in “Petrofiction” are taken up in The Glass Palace in the representation of the way the teak industry transforms social life and with more power and success in the Sea of Poppies, in which he undertakes the task of critically representing capitalism from below. The novel presents the stories of a number of people who come together as coolies and indentured workers on a ship bound for Mauritius, in the context of the Opium trade. It’s a powerful representation of the transformation of social life by the commodity. The poppy is everywhere, threaded into everyday life even as the colonial demand for its cultivation restructures society completely, forcing people into poverty and starvation. There are many wonderful things about the novel: the bringing together of the ensemble cast of renegades, fugitives and castaways on the symbol of capitalist modernity: the repurposed slave ship; the careful examination of caste, scenes of the growing friendship in prison between the Chinese-Parsi opium addict Ah Fatt and aristocratic Brahmin, Neel, that perform a way of “being together in brokenness” (Harney and Moten, 19),[5] the wonderful ending that doesn’t end, leaving the fugitives in the middle of the ocean, a powerful narrative correlative of Fred Moten’s and Stephen Harney’s fugitivity.

In the very different, The Hungry Tide, the novel that perhaps most explicitly resonates with the challenge Ghosh presents (or confronts) in The Great Derangement, Ghosh stages a confrontation between a technocratic secular modernity that has little understanding of the environment and an older knowledge of the earth, in a love triangle involving a marine biologist, Piya, looking for the river dolphin, Orcaella brevirostris, a fisherman, Fokir, and translator and businessman from Delhi, Kanai. Fokir’s wife, Moyna, who desires an urbanized upward mobility is aligned with Kanai. Fokir is a particularly fine creation—a usually silent, to many: sullen, man, with a profound and largely unappreciated knowledge of the rivers and the region. The biologist needs the fisherman’s knowledge of the river and is able to recognize its value and is thus able to see him in a way that others around him cannot. Some of the most powerful scenes in the novel are on the river or on its banks. It is an imaginative reconciliation of modern science and indigenous, older knowledge which nonetheless exposes the limitations of managerial technocracy, and my somewhat clinical and synoptic description does not do justice to the novel, which is moving and, in its engagement with nature, quite powerful, precisely because it risks sentimentality but manages not to be maudlin.

So why would a writer who can do this, who can manifest such a sympathetic imagination be so needlessly dismissive?

Perhaps the answer lies in two incidents:

In 1978 Ghosh survived a tornado. As he describes it: “the tornado’s eye had passed directly over me. It seemed to me that there was something eerily apt about that metaphor: what had happened at that moment was strangely like a species of visual contact, of beholding and being beheld.” Since then, he tells us, he has returned repeatedly to the cuttings he made from newspapers at the time with the hope of putting those events into a novel but has failed at every attempt—this leads into a long bit on notions of probability and improbability and how they affect the parameters of novelistic form.

In a section discussing the vulnerability of cities like Mumbai to climate change, he recalls approaching his mother after reading a World Bank report that made him realize that the house in which his mother and sister live borders one of the neighbourhoods most at risk. When he suggests that she move, however, she looks at him as if he had “lost [his] mind” (53). This encounter makes him realize that individuals can’t be relied on to act rationally on this; there will have be collective, institutional and statist responses to the reorganization of living required by climate change.

Both incidences are instances of Ghosh’s powerlessness: as a writer unable to represent a moment of helplessness and terror in which he thinks he wasn’t invisible to the power that could have killed him and as a son unable to get his mother to let him protect her. Neither instance is trivial, but when they are held up to the terms of his own argument they become part of its contradictions, and perhaps explain the rhetorical decibel level of the book.

The underlying suggestion in the book, that writers, critics, literature itself and to a lesser extent artists have failed Ghosh because they are unable to account for, or give voice to, his encounter with the tornado or because they cannot provide the tools to get his mother to move, makes his own concerns and experiences central in a way that would seem to align him with the high bourgeois and Romantic tradition that is very much an aspect of the era of carbon accumulation and extraction. It is a constitutive part of a moment that gives us the rise of the novel and the emergence of the modern bourgeois subject, for whom the world must turn, that Ghosh seems to want to surpass.

Yet, that Ghosh has a particular fondness for Romanticism is evident from the way that Rilke figures in The Hungry Tide. Moreover, in section 16 of Part one of The Great Derangement, Ghosh argues that the partitioning of “Nature and Culture” was resisted in “England, Europe and North America under the banners of romanticism, pastoralism, transcendentalism, and so on. Poets were always in the forefront of the resistance, in a line that extends from Holderlin and Rilke to such present day figures as Gary Snyder and W.S. Merwin” (Ghosh 2017: 69). This is also the section in which Ghosh begins by seeming to protest the hiving of science fiction from “serious” literature and ends by confirming the distinction while invoking Atwood. How Ghosh can reconcile his critique of Updike’s demand for “individual Moral adventure” in Munif’s work, and his own synoptic (and in academic circles standard and somewhat routinized) critique of the rise of Protestantism and of Protestant individualism and moralism with such an account of transcendentalism and Romanticism is a question for a longer essay.

In the preceding segment (section 15), Ghosh discusses the famous vacation that Byron, John Polidori and the Shelleys took together in 1816. Some of the writing that came out of it is mentioned: Frankenstein, Byron’s “Darkness,” Polidori’s The Vampyre. “Darkness” is cited as an example of “climate change despair,” Frankenstein as a piece of fiction that had not yet been hived of from “serious” literature” but soon would.[6] It might be useful to think about a poem that Ghosh doesn’t mention but which also came out of that vacation: Percy Shelley’s “Mont Blanc: Lines Written in the Vale of Chamouni.” The poem provides a vivid meditation on the difficulty of an encounter with the non-human, especially the non-human as encountered as sheer, raw, indifferent power and nature. At the same time the concluding (and baffling) three lines seem to articulate the human need to repudiate that which will not make itself available, that will not, that is, make itself intelligible:

And what were thou, and earth, and stars, and sea,

If to the human mind’s imaginings

Silence and solitude were vacancy?

In this era of what we now sometimes call the Anthropocene, what if what’s truly unthinkable is that, even as we have the power to affect the earth’s destiny, wrapped in its raw power, the non-human (the cyclone, the tornado, the mountain, Shelley’s “Earthquake, and fiery flood, and hurricane”) whether thunderous or silent, does not see us? What if any engagement with the non-human will have to take more seriously its sheer recalcitrance, its unavailability and opacity?

At the same time, one might remember the challenge that Edward Kamau Brathwaite poses to Shelley in his own poem “Mont Blanc,” in X/Self, a line (“it is the first atomic bomb”) from which, he writes in the notes, is: “the pivot of the Euro-imperialist/Christine [sic] mercantilist aspect of the book” (Brathwaite 1987, 118). Of course, in some ways what Brathwaite says of that line applies to the poem as whole, which thus works in powerful counterpoint to Shelley’s “Mont Blanc.” I quote here the opening:

Rome burns

and our slavery begins

in the alps

oven of europe

glacier of god…” (31)

The poem goes on to become a powerful meditation on the relationship between Europe and Africa, empire, apocalypse, European empire as apocalypse, climate change and nature. If we are to speak in broad historical terms then, even in the Romantic literary tradition, the non-human and the inhuman—the inhumanity of Europe in the name of the human—are not always easily separated. And thus, as Graham Huggan and Helen Tiffin have written in the context of a reading of X/Self, Carpentaria, and Curdella Forbes’s Ghosts, in a passage in which they also addresses Dipesh Chakrabarty’s two essays on climate change from which much of Ghosh’s argument seems derived and in response to which he appears to develop some of his arguments about the non-human:

One scenario…involves a rethinking of the human; another requires thinking beyond it. For Dipesh Chakrabarty, who is primarily concerned with the first, global warming poses a new challenge to postcolonial criticism in so far as it enjoins postcolonial critics to think, not just of the continuing history of inequality on the planet, but of ‘the survival of the species’ and the future of the planet itself (2012:15). At another level, however, global warming requires postcolonial critics to do just the opposite: to return to basic questions of inequality, including those linked to histories of slavery and colonialism, but to rethink these in ecological terms. (Huggan and Tiffin 2010, 90).

It’s probably clear by now that I don’t disagree with Ghosh that our imaginative structures and modes of identification, dominant forms of urban life, city planning, the culture of extraction and consumption, notions of the sovereign subject and habits of bourgeois moralism need to be rethought. Moreover, although The Great Derangement doesn’t much engage justifiable questions—about why the era should be called the Anthropocene and not for, instance the Capitolocene, or why the indigenous in numerous contexts whose habits of existence were not historical contributors to climate change should be yanked into the Anthropos designated by the Anthropocene—it does raise some important questions, not least for postcolonial studies: for instance did colonialism slow climate change by arresting development in places like India? What would be the consequences for re-imagining postcolonial states and political structures with that in mind? Equally significant is his argument for engaging and understanding the importance of Asia to any account of climate change, both for reasons of geography and of the size of the continental population.[7]

It is not clear to me, however, that framing the issue around the question of literature as reduced to literary fiction, even as a symptom of the undeniable imaginative social failures of modern capitalism and neoliberalism gets us there—especially as so many artists and writers and critics are trying, however inadequately, to confront the looming disaster. I say “inadequately” not because of the limitations of the work but because of the magnitude of the task and the power of the resistance to change. Perhaps the bourgeois realist novel is indeed part of the problem, especially as product of the social transformations attendant on the rise of capitalism, but then perhaps Ghosh’s sticking to an elaboration of why that is the case and of what its failures are emblematic might have helped. Misreading symptoms doesn’t often enable recovery.

The transformations of community, society and imagination needed may take many expressions, novels—realist, sci-fi, cli-fi, magical-realist, young adult—films, paintings, animations, short stories, fables, dastaans, pamphlets, tracts, synopsizing popularizations like The Great Derangement, khutbas, Papal Encyclicals… It may benefit from the talent of the griot and the skill of the journalist. And yet “revolution will come in a form we cannot yet imagine” (Harney and Moten, 11). If the argument is indeed about forms of expression and styles of thinking it needs to be made with more thought and care.

As I hope is evident from my far too short readings above, I have considerable admiration and respect for what Ghosh pulls off in Sea of Poppies and The Hungry Tide, which is what makes this book’s disappointments so very painful. At a moment in history when we urgently need to think collectively, when we need solidarity and a reconfigured sociality which, indeed, as Ghosh—like so many others—recognizes, requires (among other things) a planetary transformation of the relationship with the non-human, the dismissal of so many who are engaging in precisely the imaginative work required, simply in the service of an inflated rhetorical gesture, is more than merely baffling. To conclude, then, with the language of portents: The posture of last man standing (or, for that matter, first man railing) is no propitious augury of a transformed imagination and society to come.

References

Brathwaite, Edward Kamau. 1987. X/Self. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2009. “The Climate of History: Four Theses,” Critical Inquiry, 33 (Winter).

Ghosh, Amitav. 2017. The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

__________ 2008. Sea of Poppies. New York: Picador.

__________ 2005. ‘Petrofiction: The Oil Encounter and the Novel,” Incendiary Circumstances: A Chronicle of the Turmoil of Our Times. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.

__________ 2005. The Hungry Tide. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

__________ 2002. The Glass Palace. New York: Random House.

Heise, Ursula. 2016. Imagining Extinction: The Cultural Meanings of Endangered Species. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Huggan, Graham and Tiffin, Helen. 2nd ed. 2015. Postcolonial Ecocriticism: Literature, Animals, Environment. New York: Routledge.

Harney Stefano, and Moten, Fred. 2013. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study. New York: Minor Compositions.

Ishiguro, Kazuo. “Writers’ indignation: Kazuo Ishiguro rejects claims of genre snobbery” The Guardian, March 8, 2015

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/mar/08/kazuo-ishiguro-rebuffs-genre-snobbery, accessed August 16, 2017

Le Guin, Ursula K. 2015. a “96. Addendum to “Are they going to say this is fantasy?”” Ursula K. LeGuin’s blog, 2015. http://www.ursulakleguin.com/Blog2015.html, accessed Aug. 10 2017

__________b. “Are they going to say this is fantasy?” Ursula K. LeGuin’s blog, 2015.

http://www.ursulakleguin.com/Blog2015.html, accessed Aug. 10 2017.

Notes

[1] My thanks to R.A. Judy, Biju Matthew, Christian Parenti and Sarita See for conversation about this review.

[2] http://centerforartandthought.org/work/project/storm-typhoon-haiyan-recovery-project?page=3

[3] Would it matter, for instance, that there are numerous literary critics doing powerful and thoughtful work in the growing field of environmental humanities, and at the intersections of environmental humanities and Native Studies, Black studies and Postcolonial Studies?

[4] Obviously these examples are not even close to being comprehensive and are far too Anglophone–this is quite simply an effect of the limitations of my knowledge.

[5] The phrase is actually from Jack Halberstam’s wonderful introduction to The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study.

[6] Although, I must say I know of no literature departments in which Frankenstein would not be thought of as serious literature, partitioning or not. Moreover, having been mentored early in my current job by my dear, and now retired, colleague, Bruce Franklin, it’s a little hard to take these claims seriously.

[7] For some of the discussions about these issues in postcolonial studies, see (along with Chakrabarty’s “The Climate of History: Four Theses,” and the Volume of New Literary History, The State of Postcolonial Studies. 43:2, 2012, which contains responses to Chakrabarty’s essay in the previous volume, “Postcolonial Studies and the Challenge of Climate Change”) Ashley Dawson, Extinction: A Radical History. New York: OR Books, 2017. Graham Huggan and Helen Tiffin, Postcolonial Ecocriticism: Literature, Animals, Environment, New York, Routledge, 2015. Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011. Jennifer Wenzel et al. Fueling Culture: 101 Words for Energy and Environment. New York: Fordham University Press, 2017. Of course, this list is far from exhaustive.