This post is Part Three of “The Bangladesh Chapter” of the b2o review’s “The University in Turmoil: Global Perspectives” dossier.

How to Capture a University: Lessons from Dhaka

Shrobona Shafique Dipti, Naveeda Khan and Bareesh Hasan Chowdhury

Figure 1: Dhaka University.

Figure 1: Dhaka University.

The Cast of Characters

Sheikh Mujib, Founding father of Bangladesh

Sheikh Hasina, daughter of Sheikh Mujib, head of AL, and till recently Prime Minister of Bangladesh

AL, Awami League, the ruling party

BCL, Bangladesh Chhatra League, AL student wing, also referred as Chhatra Leaguers

BNP, Bangladesh Nationalist Party, opposition party

JI, Jamaat-e-Islami, religious party

Shibir, JI student wing

Hefazat-e-Islam, coalition of religious parties and groups

DU, Dhaka University

BUET, Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology

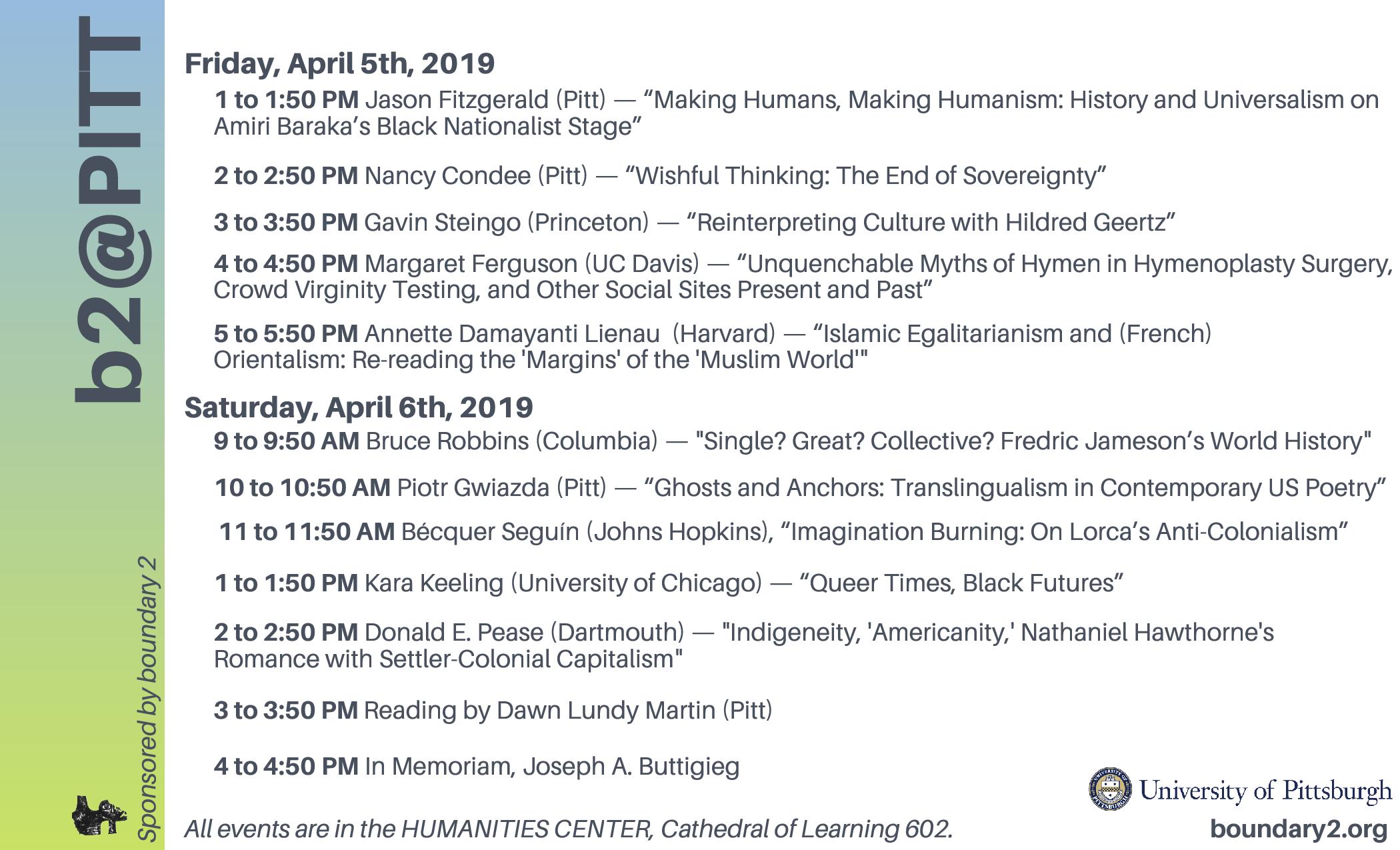

Universities in Comparative Perspective: Two Types of Capture

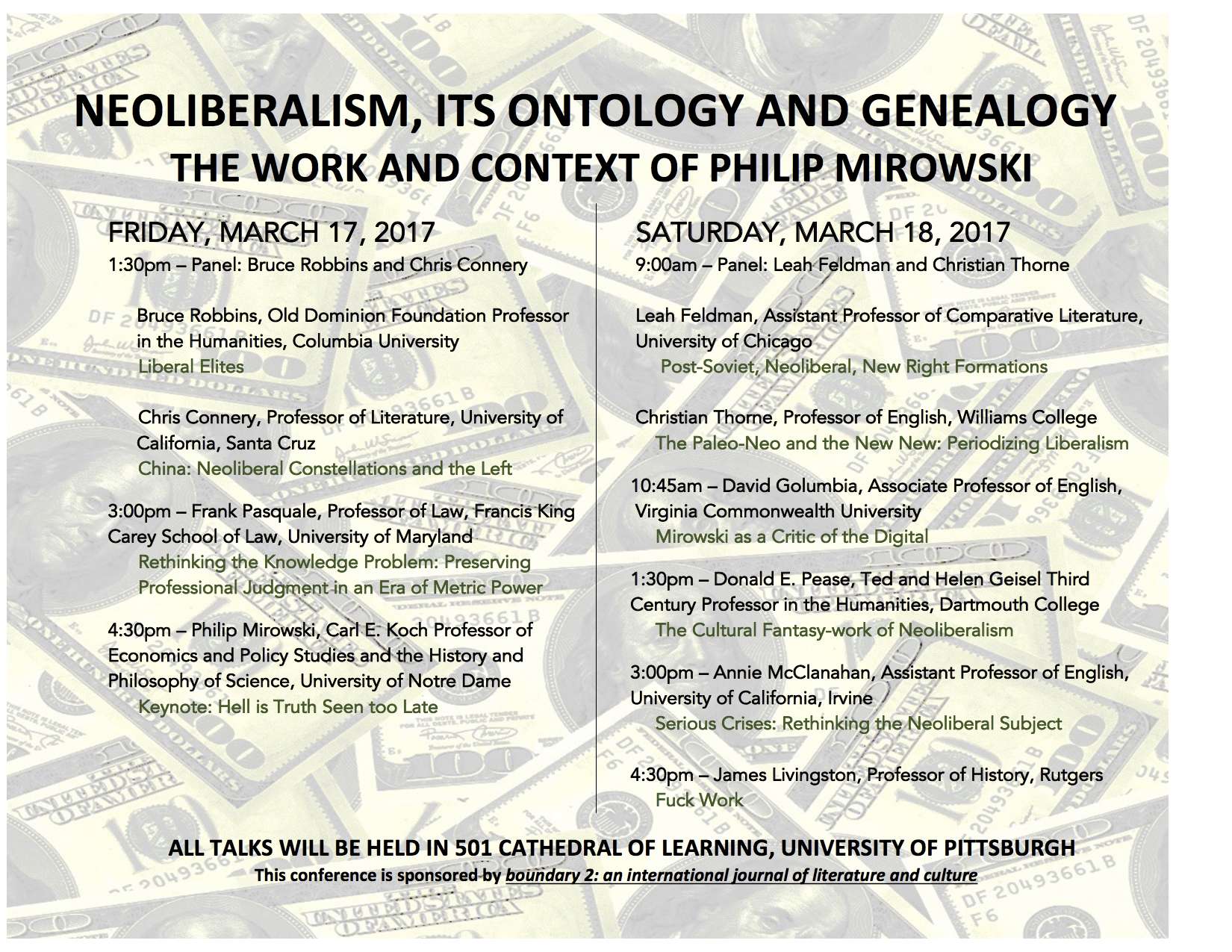

2024 will surely go down in history as the year that students in U.S-based universities revolted against their government’s stance on Gaza. Expressions of gratitude emblazoned on the tent roofs of displaced Gazans gave voice to an almost global appreciation of the students in the face of threats by university administrators. While for a bit it seemed that university campuses were the last bastion of free speech in the U.S., the subsequent attacks by police on students at the behest of administrators made clear that universities in the Global North were already captured spaces and had been for a long time. Between zealously grown and protected endowments, entrenched boards of trustees, and administrative bloat, faculty, students, research and teaching had long been mere excuses for the existence of corporatized universities.

In other parts of the world this pernicious combination of liberalism and capitalism has not quite set in the same way, although there are some indications that it may yet do so, judging by the growing numbers of private, for-profit universities in places where capital is rapidly accumulating, such as China and India. Consider, for instance, the case of Bangladesh. Here public universities, such as Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET) and Dhaka University (DU) – both British, colonial-era institutions – are still hallowed places of education and training, where teachers are respected, and young Bangladeshis strive to get admission to better their life chances. This has remained the case even as the Bangladesh economy has turned rapaciously capitalist, private universities steal away teaching talent, and university coffers are depleted, with a baleful impact on infrastructure and services.

But it is not the case that universities of Bangladesh are free of capture. The capture is just of a different kind than that by capital. Historically, university students, most notably at Dhaka University, have been associated with anti-colonial and nationalist politics. Since Bangladesh’s independence from Pakistan in 1971, political parties have evolved student wings that carry out a version of national politics on campus. Depending on which party is in power, their equivalent wings dominate in universities, extending into higher education the politics of patronage and insinuating themselves into the lives of students.

Given this scenario, it was quite shocking to most that the 2024 Student Anti-Quota Movement, very clearly critical of the government headed by the Awami League (AL), started from Dhaka University, which was at that point very much under the thumb of the Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL), the student arm of the ruling party. Given this unlikely development, it is incumbent upon us to inquire how a space as state dominated as Dhaka University could also be the site of an anti-state revolt. It requires us to inquire how the BCL’s vice grip upon the campus may have created the conditions of possibilities for its downfall. The battle within the university grounds on July 15th, 2024, when the Awami League let loose BCL students upon peers involved in the Anti-Quota Movement, an encounter which ended in considerable bloodshed, death, and the chilling images of Chhatra League men in helmets with hockey sticks bearing down on unprotected bodies – often with the support of law enforcement authorities –will probably serve for all time as the moment when Bangladesh civil society realized that the Prime Minister and her party had gone mad.

In Part Three of “The Bangladesh Chapter” of the b2o review’s “The University in Turmoil: Global Perspectives” dossier, we explore the spatial experience of the university as a captured space, that is, how the AL-led government and its student wing came to take over the space of the university, before turning in our next contribution to how this space was reinhabited to launch a movement against the state. We hope that getting a sense of the lay of the land may provide a glimpse into how small incursions into space becomes a full-throated capture of every domains of existence, including the imagination, and what living under active oppression feels like while one is trying to simply go about the business of getting educated.

Mapping Dhaka University

Dhaka University occupies a central location in the capital, on the way from the older residential neighborhoods of west Dhaka to the business district in the east, but which, crossroads though it may be, still feels like a haven, thanks to its wide roads, tree-lined avenues and historic buildings set back from the roads. In this section, we provide in three maps an overview of the location and layout of the university before homing in on the monuments that dot its landscape and that provide an important vantage on how students have been central to politics in Bangladesh, for better or for worse.

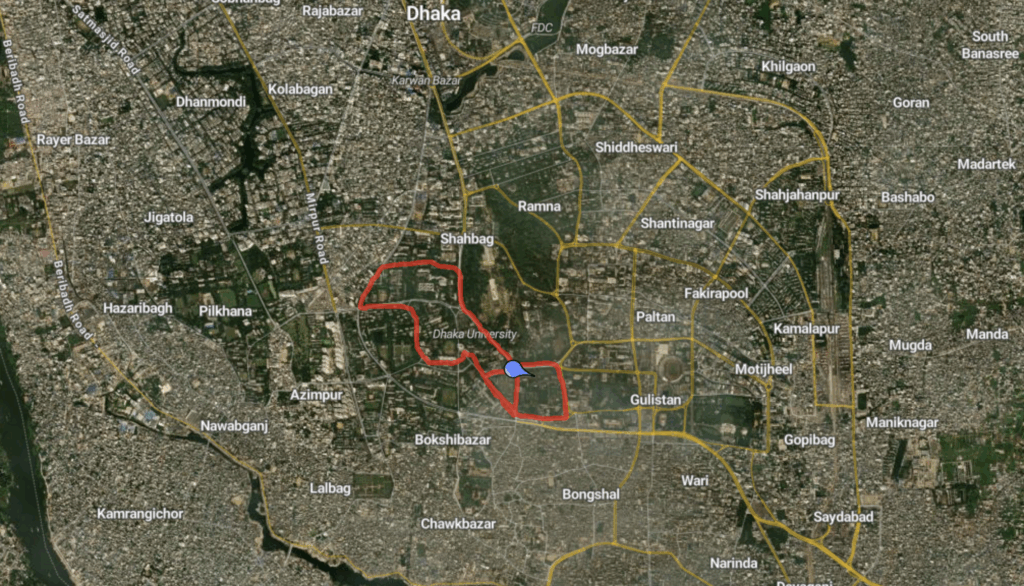

Map 1.

Map 1.

The first map shows the form of the university area and its placement within the heart of downtown Dhaka. We see that it is relatively green, indicating trees and parks in its vicinity, such as the Ramna Park, a site of romantic liaisons, sports, and other leisure activities. Otherwise, very densely occupied neighborhoods and areas throng the campus.

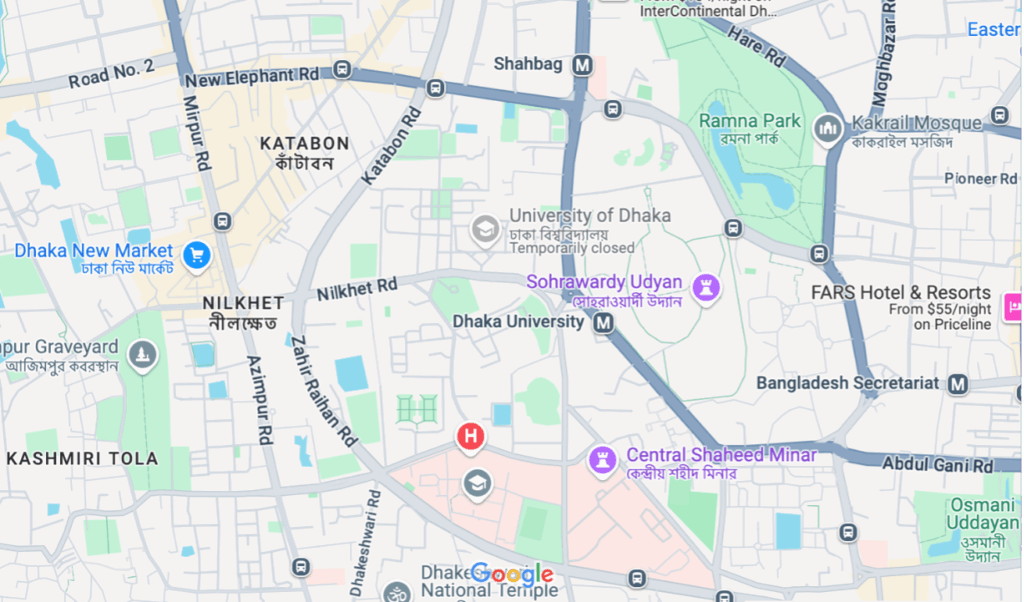

Map 2.

Map 2.

The second is a road map of the University. When we zoom into it, we see that the campus is overlaid by four roads, although university buildings spread out beyond these thoroughfares: the New Elephant Road to its north, Kazi Nazrul Islam Avenue/Abdul Gani Road somewhat to its east, Nilkhet Road to its south and Azimpur Road to its west. All four of these roads are busy commercial thoroughfares and sites of important student mobilization.

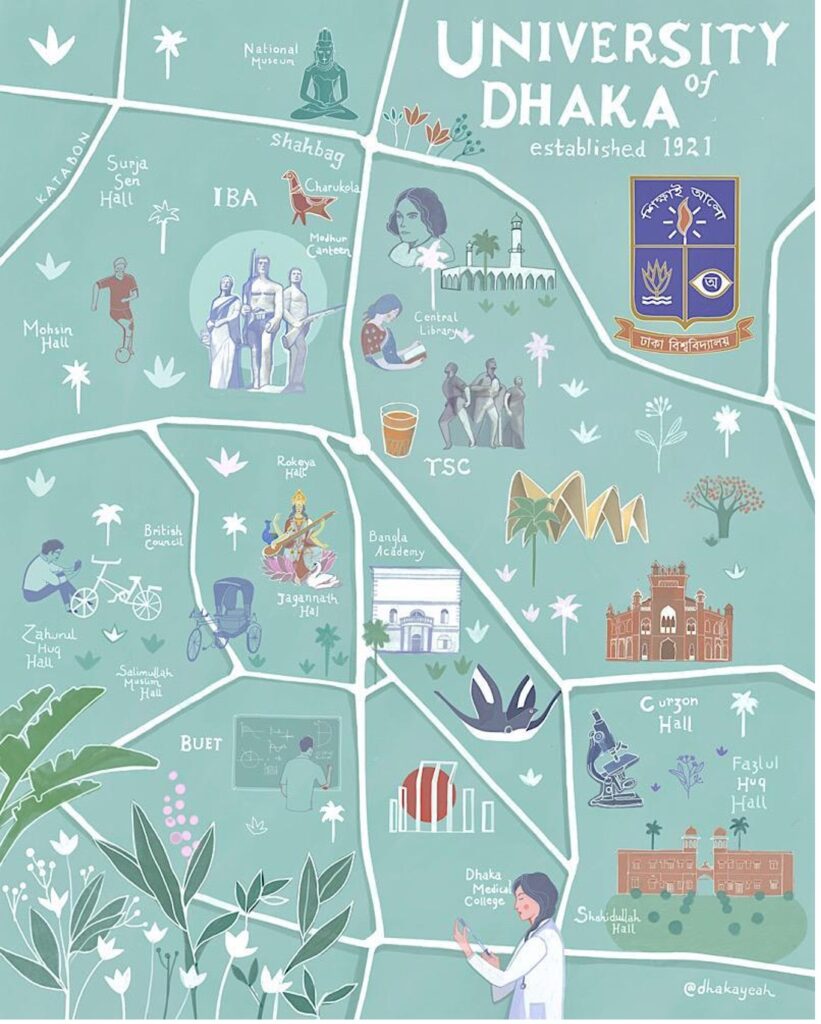

Map 3.

The third map is a creation of the graphic art group Dhakayeah, known for producing images of urban and semi-urban areas of Bangladesh – visual pastiches, suffused with elements of the past, espousing a certain romantic view of Bangladesh as both familiar and lost. The pale green color palette reinscribes this view. The image of a woman in a white overcoat and that of a woman in a sari perusing a book alongside the image of a man sitting on the grass looking at something or the man playing football puts forward the university as a co-educational space. While we are alerted to the distribution of educational buildings through icons indicating laboratories, libraries, science, art, etc., and we are also given the names and images of several historical buildings and cultural sites, such as Curzon Hall, Shahidullah Hall, Bangla Academy, National Museum. Among the residential buildings, the one for non-Muslims, primarily Hindus, Jaganath Hall, is indicated by the icon of the Hindu Goddess Saraswati, associated with wisdom, with her sitar and white goose.

On the Dhakayeah map we are pointed to the presence of notable monuments, such as the Central Shahid Minar (Martyrs Monument), the 1963 national monument to the martyrs of the 1952 Language Movement composed of five forms of white pillars and arches. There is the 1979 sculpture of three freedom fighters holding guns, including a woman, titled Aparajeyo Bangla (Unvanquished Bengal) to commemorate the 1971 liberation struggle. The Anti-Terrorism Raju Memorial, composed of men and women looking outwards while forming a circle with interlocked arms and hands, was created in the late 1990s to commemorate the student Moin Hossain Raju, killed while protesting terrorism within the university campus.

Figure 2, ©jagonews24.

The map represents several others, but inevitably omits many, as the campus is awash in monuments. One significant to the story of how the campus has come to be the resting place of the memories of violence faced by the country’s young is called the Road Accident Memorial, unveiled in 2014 and representing the car crash that killed the Bangladesh filmmaker Tareque Masud and his companions in 2011. These memorials, like others, indict the country’s two major political parties, the Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), for their reigns of violence and neglect of student safety. These monuments were once counterpoised by large murals of Sheikh Mujib, the founder of Bangladesh, and Sheikh Hasina, his daughter and Prime Minister of Bangladesh until 2024, on the pillars of the Metrorail. The murals were defaced during the Anti-Quota Movement (figure 2), but are worth keep in mind, as we note how monumental sculptures and images indicate the diverse political strivings of the university students.

A Recent History of the University, 1990s-2020s

To understand our story of the capture of the university by the ruling party, and the seeds of unrest that this planted, it would help to trace the recent history of Dhaka University from 1990 to the present. In the early part of the period, we see students becoming involved in national movements to depose a dictator, but also teachers and administrators getting politicized. In the later part of this period, we see the student wing of the ruling party consolidating its hold on the university with the aid of senior administrators. We also see the university expelling all other student parties across the political spectrum.

1990 stands out as the year in which a broad swathe of civil society organized to lead a movement against the standing military leader turned dictator, General Ershad. Students at Dhaka University were part of this movement. What is particularly noteworthy in the decade following Ershad’s being forced out of power was the entrenchment of teachers within national politics by means of the university. Until the 1990s, it was students who had played a conspicuous role in national politics through the student wings of various parties, but the 1990s brought party-linked teachers’ organization to the fore: the BNP-backed teachers of Shada Dol (White Party), for instance, or Awami League-backed teachers of Nil Dol (Blue Party). The students remained markedly more influential than their teachers within this changing dispensation; it was students, for instance, who secured positions for teachers, such as those of the vice chancellor, proctor and hall provosts. The teachers expressed their gratitude through shielding and protecting students from criticism and the repercussions of their violent acts.

The next two decades, the period from 2000 to 2019, saw the steady encroachment of the state into the university, leading to growing political influence over university governance, including the dispensing of justice. One event that especially colored this period was the 2010 murder of Abu Bakar, widely regarded as a student of great promise, who was killed during clashes between two Chhatra League factions fighting for control over access to a room in a residential hall referred to as a “hall seat.” Despite overwhelming evidence, the students accused of his murder were acquitted, and the victim’s family was not even informed of the verdict. Even the President of the country ignored the family’s appeals for justice. Such incidents were in step with the state growing in power in the country more widely, and starting to perpetrate violence against its own citizens, in the form of enforced disappearances and illegal detentions.

Figure 4, ©Maciej Dokowicz.

Figure 5, ©JagoNews24. Scenes from Shapla.

Figure 5, ©JagoNews24. Scenes from Shapla.

Figure 6, ©Syed Zakir Hossain.

Figure 6, ©Syed Zakir Hossain.

This period also saw the rise of sizeable movements in which university students, including seminarians, played a leading role. Two, the Shahbag Protests of 2013 and the Shapla Square Protests of the same year, were defining moments in the country’s recent history, driving home the cultural divides that marked the Hasina era. Locating themselves at one of the main entry points of Dhaka University, tens of thousands of people participated in the Shahbagh Movement, which were led by pro-liberation activists, aligned with Bangladesh’s bid for self-determination from Pakistan in 1971, and strongly supported by left-leaning Dhaka University students. These activists expressed their desire for the state to impose stiff sentences, including death, on those they considered war criminals for having sided with the Pakistan army in 1971, for having, that is, assisted in the violence that the army inflicted against East Pakistanis at that time. When the war criminal Abdul Quader Molla was handed a life sentence by the tribunal overseeing his trial, the movement demanded that he be sentenced to death instead. The movement thus served the state’s interests by pushing for the rigorous punishment of those seen as traitors to the nation – Molla’s sentence was transmuted, and he was promptly hung; it was also used by the state to suppress the political activities of the student wing of the religious party Jamaat-e-Islami’s student wing, and other groups within the university campus.[1]

This movement was followed by the Shapla Square Protests, led by Hefazat-e-Islam, an advocacy group consisting of religious leaders and students within the Qawmi Madrasa system, a privately run religious educational system parallel to the state-run one. They called for the adoption of a blasphemy law, citing perceived offences to religious sentiment caused by Shahbag protesters. This movement ended in a violent crackdown, with security forces brutally dispersing protesters. Even though Hefazat as a group backed the war crimes trials, which was used to persecute leaders of Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) Bangladesh, JI and its student wing Shibir, contributed heavily to the group, seeking common ground against the Awami League and a shared goal of integrating Islam into Bangladesh’s governance and laws.

The two movements, Shahbagh and Shapla, symbolized a deep political and cultural divide: Shahbagh was framed as upholding the spirit of 1971 (muktijuddher chetona), while Shapla was portrayed as anti-liberation (bipokkho shokti). This binary allowed the government to homogenize and demonize madrasa students and anyone visibly religious, such as those with beards and skullcaps, as enemies of the state. By constructing this division, the ruling party justified widespread repression under the guise of protecting the nation’s independence, a strategy that they continued for the next decade.[2]

While the Shahbagh and Shapla movements have provided the frame for political narratives since 2013, Dhaka University students also led the first version of the anti-quota reform movement that same year. Though overshadowed by the massive Shahbagh movement, anti-quota activism would return in 2018 and again in 2024 to challenge the established polarities of the nation’s politics, its divvying of the field between progressives and reactionaries, that framed the Awami League’s encroachment upon and the Chhatra League’s dominance on the DU campus and elsewhere.

The Micro-capture of University Space

Amid this growing capture and repression of the university by the state by means of its student wing, the entire social, cultural, and educational landscape of the university underwent a transformation. Chhatra League’s dominance extended beyond student politics, infiltrating academic and professional spheres. Academic opportunities, teaching positions, and even government jobs increasingly required loyalty to them. Many joined not out of ideological conviction, but as a means of survival: to secure protection from violence, gain access to institutional privileges, or ensure career advancement. But once they joined, they soon learned of the BCL’s mode of operation: the loyalty that it expected of its members and the incessant jockeying for power within the organization.

The president and general secretary of the Dhaka University branch of BCL were considered the most powerful positions within the branch, as these served as steppingstones to central leadership within the all-Bangladesh student party. So important were these two posts that both the national media and the wider student body watched to see who secured them. Those who aspired to political careers on the national scene often prolonged their studies artificially, declining to complete their degrees to hang onto positions of influence. Departments were organized to allow students to stay enrolled despite failing their exams multiple times. In fact, the longer one stayed at the university, the greater were one’s chances of rising to the top.

Students within the Chhatra League competed for these positions. Having control over hall committees, enjoying a monopoly over rackets enabling rent seeking and patronage, known locally as “cartels,” and cultivating close ties with the university administration all contributed to one’s prospects of rising through the ranks. And the path to leadership began within the residential halls. Political leaders often referred to their time in the halls as laying the foundation for their careers.

At Dhaka University, the number of students admitted often exceeded the available accommodations, leading to overcrowding. As a result, the university authorities had long ago stopped offering housing to first-year students, leading to tremendous insecurity for those coming from outside Dhaka or from poorer backgrounds, given the exorbitant rental costs in the capital. Hall leaders, backed by their loyal followers, consolidated power by securing the support of hall provosts and house tutors. Through such political maneuvering, BCL activists gained control over specific rooms, with Chhatra League leaders and their followers receiving rooms more easily.

The leaders typically had separate rooms with amenities, while students, depending on their patronage of BCL activists, were assigned spaces within rooms, called Gonorooms (mass dormitories), which housed 20-30 students, far exceeding their normal capacity. They were overcrowded, unsanitary environments, severely affecting students’ health and well-being. Nonetheless, the premium on space meant that they were sought after and served as spaces of control and political tutelage. For instance, students new to Chhatra League were required to attend Guest Room sessions, where they were instructed on so-called political courtesy, including how to show deference to student leaders. These sessions often lasted several days; refusal to participate often resulted in bullying and even physical abuse. Fear was pervasive, as the Chhatra League’s power was absolute as they had both impunity and deep resources to draw on to impose their will.

The 2016 death of Hafizur Molla, a student from the Marketing Department of Dhaka University, highlighted the harsh living conditions and political control exercised by the Chhatra League over students at the university. Molla moved into Salimullah Muslim Hall in January under the good graces of a Chhtra League activist, but was forced to sleep in the veranda, which some halls also use as makeshift living spaces. Less than a month after his admission, he contracted pneumonia and typhoid and died. His family and classmates claimed that his illness worsened due to the exposure to cold living in the veranda and being forced to attend Chhatra League nightly programs, including AL-led political processions.

This power over students and their residential lives extended to the food canteens in the halls. Canteen owners were required to provide food and stay open late to serve the leaders or else face beatings and assaults. According to an example provided by the newspaper Daily Jugantor, leaders ate food worth 18 lakhs of takas ($18,000) from the canteens between 2019 and 2024 without paying for it. In turn, the canteen owners passed on their losses to the students, who had to pay inflated prices for their food, while the canteen ownership saw a fast turnover.

Despite widespread awareness of the ongoing situation at Dhaka University and other campuses, one incident deeply shook the public. This incident occurred not at Dhaka University but at the neighboring Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET), a campus traditionally known for its apolitical stance. On the night of October 6, 2019, Abrar Fahad, a second-year BUET student, was tortured to death by Chhatra League activists inside Sher-e-Bangla Hall. The attack was likely brought on by his Facebook post, which was critical of India. Accused of being affiliated with Shibir, the religious student wing – a common justification for violent hazing – he was severely beaten. CCTV footage later showed his lifeless body being dragged down the stairs, an image that quickly spread across the country through national media. In response to Abrar Fahad’s murder, BUET students launched a massive protest demanding justice and the banning of political activities on campus. This movement led to the BUET administration officially prohibiting student politics, marking an unprecedented step by an avowedly apolitical but also relatively passive administration, which now committed to quashing student influence within public universities.

Figures 7 and 8, Modhur Canteen, 1904 and Present.

The BCL’s mode of extending its influence over the campus was to capture sites that had historically been associated with the fight for freedom (of various kinds) and that retained symbolic importance within the history of the university. One such site, Modhur Canteen, was long associated with student social gatherings and political activism. Originally a dance hall in the garden house of a zamindar from Srinagar, on whose property Dhaka University was later built (figures 7 and 8), it would host the planning of significant student-led anti-government movements in 1948 and 1952. During 1971, Madhusudhan Dey otherwise known as Modhu Da, the man who served in the canteen, was shot dead by Pakistani forces. After independence, the canteen came to bear his name in recognition of his sacrifice. Its symbolic importance for student politics is indicated by the fact that it became the site of press conferences by various student wings.

Figure 9, ©Jannatul Mawa.

Figure 10, ©amarbarta.

Figure 10, ©amarbarta.

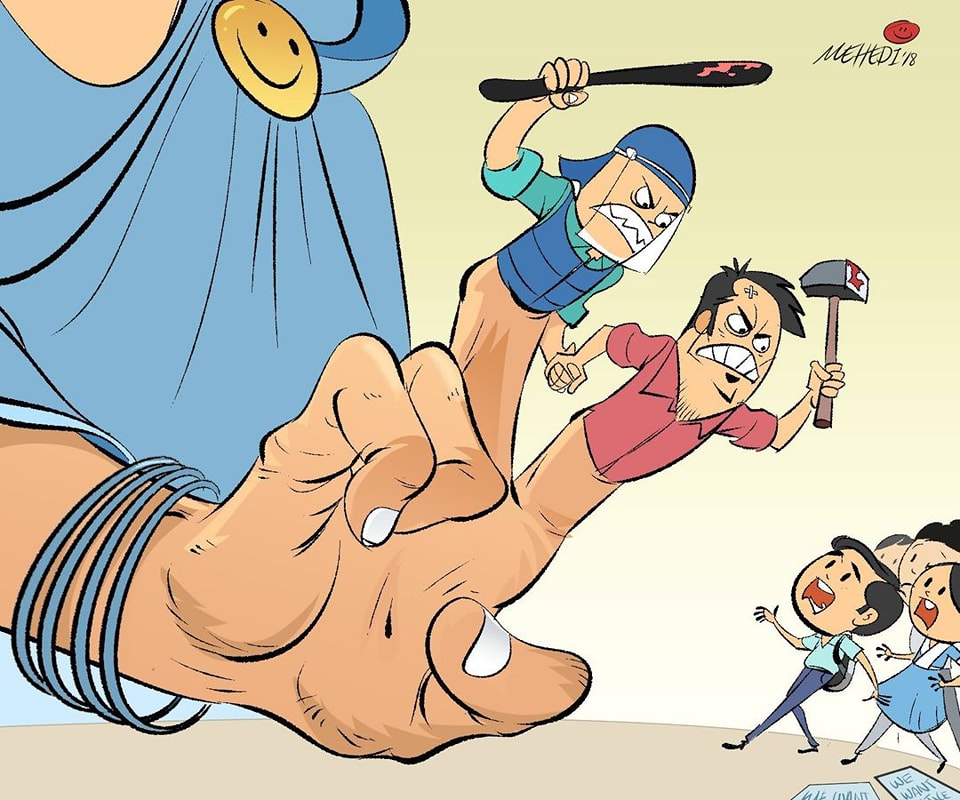

Figure 11, ©Mehedi Haque.

Figure 11, ©Mehedi Haque.

Under the BCL the canteen became a site for the performance of power by their leaders. After gaining control of the space, its leaders arrived every day on motorcycles, revving their engines to produce an awful din. Their helmet-covered heads and shielded eyes gave them an ominous look. This look even acquired a certain iconic character (figures 9, 11 and 13). Modhur Canteen also served pragmatically as the site of BCL meetings. Factional infighting took place here in full view of passersby and those living close by (figure 10).

Another example of a space captured, and its original symbolism overturned was the Teachers-Students Center (TSC). The capture of TSC allowed Chhatra League to expand its scope from being a political force to asserting cultural hegemony, becoming the “Cultural Chhatra League.” TSC housed a cafeteria, beside which stood the Anti-Terrorism Raju Memorial Sculpture, a significant piece expressing the students’ struggle for spaces to learn without the threat of political violence (see section “Mapping Dhaka University”). TSC’s auditorium and rooms were allocated for various long-standing and popular students – film, IT, debate, etc. In time these clubs too fell under the control of Chhatra League. Club leaders had to be affiliated with BCL. This included the presidents of the film and debate clubs, which had once been the most independent-minded of the student clubs, generating high levels of cultural and political excitement, but which now operated under Chhatra League’s command.

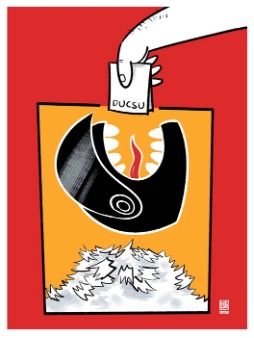

TSC was once a stronghold of leftist political organizations. Even as the clubs fell under BCL control, they maintained some independence by putting on concerts, film screenings, and other cultural events. However, the rigged Dhaka University Central Students Union (DUCSU) election of 2019 (discussed below) brought about a drastic change, tilting the Center entirely into BCL’s camp. All funds allocated for cultural activities were appropriated by the BCL, which started organizing large concerts with massive banners and extravagant expenses amounting to lakhs of takas ($100,000s), both as a racket and to draw attention to their presence and power. Without any school funding, the leftist groups were forced to rely on crowdfunding. While the much-weakened leftist groups were allowed to stay on campus the student organizations affiliated with the opposition Bangladesh National Party (BNP) were expelled from campus in 2010. The party was then allowed to participate in the 2019 DUCSU elections – and thus allowed back on campus in some limited way – because elections, even rigged ones, require opposition groups and BNP was deemed the most acceptable of the lot. Students affiliated with Jamaat-e-Islami and other religious parties were forced to hide their political identities or else were banned from campus. In fact, dissimulating one’s political identity became the norm.

Women in the BCL

Although there were women in the Chhatra League, they were often excluded from the image of Chhatra League politics, where leadership was typically associated with men – the kind of men who led motorcycle processions, exerted control through violence, carried out extortion, and exuded dominance by wearing biker helmets as though they were armor. Women’s spaces were also a site of BCL power politics, though of a muted kind. And while not free of the BCL’s clientism, they still provided the space for some iota of resistance.

As a resident of Ruqayyah Hall, one of us, Shrobona, witnessed firsthand how power operated in women’s halls. While the violent capture of student halls by Chhatra League members was rampant in men’s dormitories, women’s halls experienced a more subtle form of control. Rooms in each hall were designated for Chhatra League leaders—at least two to four per building spread across different floors. These rooms belonged to senior apus (sisters), each of whom had her own group of followers. Some of these followers joined the BCL willingly, hoping to advance in politics, while others were recruited for reasons of geography or because they were squatting and were vulnerable to intimidation. Women who were conventionally attractive and deemed obedient were often targeted for recruitment.

Every week or month, these women were required to meet with BCL leaders, who then selected a few to be introduced to party officials at the AL headquarters. Despite never holding major leadership positions, these women were often deployed to suppress protests. I remember one such incident when we marched to the Vice-Chancellor’s office to protest sexual harassment. There were around 200 students, yet Chhatra League mobilized nearly 2000 men and women to attack us – under the pretext of protecting the university administrator.

While residents were only allowed to stay out until 10 PM, female Chhatra League leaders could enter halls at any hour of the night. There were extravagant birthday celebrations of apu leaders. One such event went viral during the 2024 protests that led to Hasina’s downfall. In the footage, Atika, a BCL leader from Ruqayyah Hall, was seen celebrating her birthday in grand style, with the TV room lavishly decorated with flowers and followers chanting slogans, a festivity that seemed ill-judged at a time of national crisis.

Unlike men’s halls, where religious segregation was enforced (e.g., male students of minority religions had to stay in Jagannath Hall and were not welcome in the other halls), women’s halls accommodated students of all religious backgrounds. This encouraged a degree of pluralism. While BCL monopolized university-wide cultural activities – determining, for instance, who could or could not participate in sports, debates or music – Hindu festivals, such as the Saraswati Puja, were celebrated within the women’s halls, providing some spaces for socializing outside of BCL control.

Women’s halls were also frequently sites of protest, as students came to challenge the treatment of rooms as property and the partisan exploitation – indeed, extortion – of hall resources. During the fasting month of Ramadan, female students protested the unfair distribution of food, although dissent was soon suppressed by hall authorities threatening to revoke residence permits. One striking example of resistance to the consolidation of power within the hall emerged following the 2019 DUCSU election. Professor Zeenat Huda, the provost of Ruqayyah Hall, was accused of colluding with Chhatra League leaders in demanding Tk 21 lakhs in bribes for university jobs in the Class IV category, that is, lower administrative jobs. Two students posted on social media an audio recording of a conversation in which the demand was made. In retaliation, the provost canceled their legally allocated residential seats.

The 2019 DUCSU Elections: A Turning Point?

Figure 12, ©Maloy Kumar Dutta.

Figure 13, ©Reesham Shahab Tirtho

The Dhaka University Central Students’ Union had long been a crucial means of political engagement in Bangladesh for students. Sultan Mohammad Mansur Ahmed, elected as DUCSU Vice President (VP) in 1980 during the Ershad era, underscored the enduring importance of the union in shaping the political trajectory of Bangladesh. He remarked in 2019 that, “If we consider DUCSU only as the Dhaka University Central Students’ Union, its significance will not be fully understood. DUCSU has served as the birthplace of Bangladesh’s liberation struggle and all democratic movements. From the Language Movement to the fight for self-determination and independence, DUCSU has led every major political movement.” After Bangladesh’s independence, DUCSU continued to serve as a platform for political dissent, notably in the 1990s, when it spearheaded the student uprising that ultimately led to the fall of Hussain Muhammad Ershad’s military dictatorship, mentioned above.

There is a stark irony in the fact that DUCSU elections were regularly held during both the Pakistan era and General Ershad’s rule. However, after the 1990 uprising that toppled Ershad, the tenure of those who had been elected in 1990 was allowed to lapse without another election for 28 years. Between 2016 and 2018, left-wing and non-partisan student activists campaigned for elections to be reinstated, seeing these as a solution to the deteriorating conditions on campus. Through the DUCSU Chayi (We want DUCSU) movement, they organized protests, gatherings, and graffiti.

Surprisingly, after decades of inaction, the Awami League government agreed to hold Student Union elections in 2019, just months after the notoriously rigged national elections of December 2018. This was thought to be a concession, as demands for change had been gaining momentum on campus. The 2018 Anti-Quota Movement, led by Nurul Haq Nur, had launched a popular panel, Bangladesh Sadharon Chhatra Odhikar Songrokkhon Parishad (Bangladesh General Students’ Rights Protection Council). Meanwhile, a new student group, Shotontro Jot (Independent Alliance), emerged, consisting mostly of non-resident students from the science departments who claimed to be apolitical and sought a campus free of partisan influence. Leftist student groups also organized campaigns, addressing critical issues such as the entrenched system of loyalty-based politics (lejurbrittik rajniti), the overcrowded and exploitative conditions in Gonorooms (mass dormitories), and the poor quality of food in campus canteens. Their manifestos called for greater rights for students and a better quality of campus life.

Any hope for change was badly shaken when the Student Union began to resemble the discredited national election. The AL-government’s apparent concession to student demands appeared to be mere window dressing. For instance, on the night before voting, ballot papers were discovered hidden in a canteen storeroom. Students and candidates stood guard to prevent further interference, but BCL activists forcibly entered, clashing with hall tutors and teachers as voting descended into chaos. When students discovered rigged ballots in another residential hall, they demanded the provost’s resignation on the day of voting. Despite widespread protests, threats of boycott, and calls to halt the election, officials rushed through with the process and counted the votes.

To appease the students at large, the BCL strategically conceded the VP position to Nurul Haq Nur, the leader of the 2018 Anti-Quota Movement and a general position to a member of his party, while securing control over the remaining 23 positions. Upon his election, Nur visited the parliament in session and controversially praised Sheikh Hasina as the “mother of education.” His statement shocked many students who had hoped for continued resistance, reinforcing skepticism about whether any real change was possible within the existing political structure. But what became clear from the 2019 DUCSU elections was that student participation and protests directly challenged the dominance of the Chhatra League.

In Conclusion

Even in a space as thoroughly captured as Dhaka University, resistance fomented. As the gains from the previous 2018 Quota Movement were eroded back to nothing, above all through the 2024 High Court ruling that reestablished the hated quotas for the family members of freedom fighters, students in various universities took to protests. What such spontaneous protests showed more than anything else was that students maintained a belief in the power of collective action above all else. The monuments we spoke of earlier that dotted the campus of Dhaka University embodied this belief. And as we saw in the sketch of student politics over the past few decades, despite all efforts at repression by BCL, the space of Dhaka University was riven by unrest always just below its surface, materializing in intermittent protests. In effect, the July Movement of 2024 that toppled the Awami League government and its mode of student politics could be taken to be just one more protest along a long trajectory of such protests. We next move to the scene of the movement to explore how it became the means of undoing an authoritarian regime and the possible undoing of the state capture of the university campus.

Naveeda Khan is professor of anthropology at Johns Hopkins University. She has worked on religious violence and everyday life in urban Pakistan. Her more recent work is on riverine lives in Bangladesh and UN-led global climate negotiations. Her field dispatches from Dhaka in the middle of the July Uprising may be found here.

Bareesh Hasan Chowdhury is a campaigner working for the Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association on climate, policy, renewable energy and human rights.

Shrobona Shafique Dipti, a graduate of the University of Dhaka, is an urban anthropologist and lecturer at the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh with an interest in environmental humanities and multi-species entanglements.

[1] Through these trials much of the leadership of Jamaat-e-Islami was also executed. There were also torture and repression of students at this and other universities, such as Rajshahi University under the presumption that they were supporters of JI or Shibir.

[2] At the same time as the religious right was being suppressed, there was considerable concession to their demands. The 2018 Digital Security Act allowed in through the side door the surveillance and punishment of utterances deemed blasphemous by criminalizing any insult to Sheikh Mujib, the founding father of Bangladesh, and the Prophet Muhammad.