This text is published as part of a special b2o issue titled “Critique as Care”, edited by Norberto Gomez, Frankie Mastrangelo, Jonathan Nichols, and Paul Robertson, and published in honor of our b2o and b2 colleague and friend, the late David Golumbia.

Witnessing Corecore as an Epideictic Call to Care

Caddie Alford

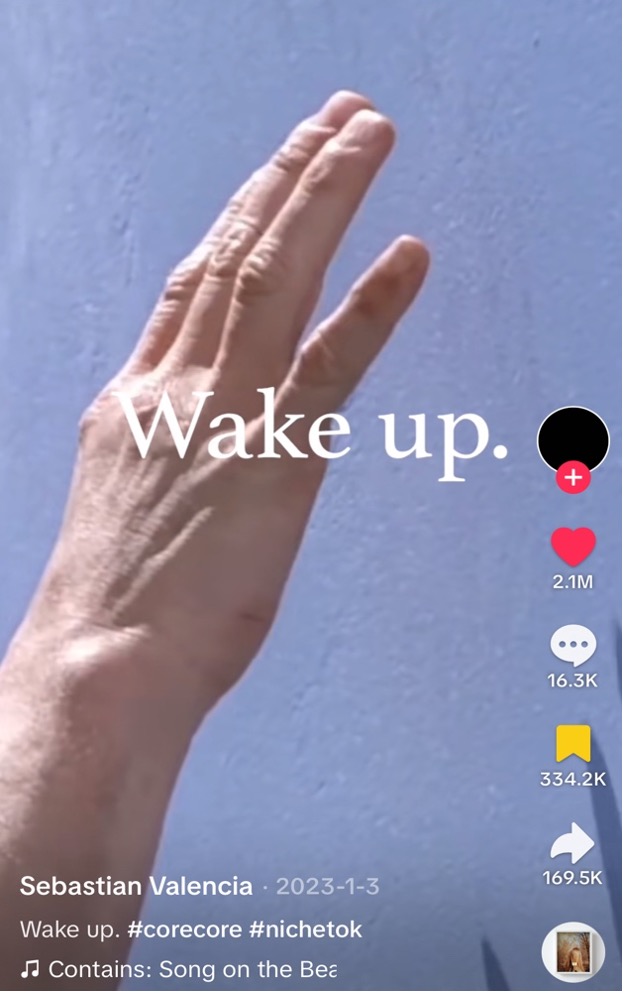

It’s early January 2023. You’re on TikTok. Comedian Bo Burnham’s song “Microwave Popcorn” has become viral audio.[1] Banking on that virality, user @sebastianvalencia.mp4’s video starts with Burnham’s unmistakable “I put the,” but before “packet on the glass” plays, the video skips to another “Microwave Popcorn” video, then another, then another, and then a high-pitched buzzing gets louder over a scrolling blur of videos from a “sad Family Guy edits” playlist. The video cuts to black and the words “Wake up” appear. Some lilting piano notes begin to play over a shot from the 1998 film The Truman Show, which transitions into an interview with comedian Hasan Minhaj saying, “The internet and technology created an idea of infinity. And the reason why life is beautiful is because it is fundamentally limited.” That quote tees up animations from the 2008 Disney Pixar film WALL-E of humans glued to devices and media, spliced with clips of actual humans walking around head down with their phones in front of them. Mark Zuckerberg’s infamous 2021 brand change announcement starts playing—“Today, we’re gonna talk about the Metaverse”—but only long enough to cut back in time to his somber and shaky 2018 testimony to Congress: “it’s clear now that we didn’t do enough to prevent these tools from being used for harm as well.” More from Minhaj’s interview rounds everything out before cutting back to black. The video—this stew of obvious yet idiosyncratic contrasts—has 2.1 million likes.

Screenshots of two cuts in sequential order from @sebastianvalencia.mp4’s corecore TikTok video, 2023.

The above style of editing on TikTok is called “corecore,” which is a genre that dramatizes a fraught relationship with TikTok’s -cores, or suffix tags that index micro aesthetics. Corecores elicit the platformization of feeling—“vibes”—ranging from poignant to maudlin. Corecore edits can be disorienting like other odd editing trends, but they’re somewhat outside trend categories. Since #corecore is, as post-disciplinary duo Y7 explain, “a category defined by the very act of categorization,” there isn’t the same “immediate implication of an aesthetic” as you might see with a weirdcore edit or meme, which is an aesthetic that consistently pulls from early internet graphics (Y7 2023). No, corecore “took trends and trending as its subject” (Y7 2023).

On January 1, 2021, user @masonoelle may have been the first to create a corecore with, as always, a fairly slapdash compilation of clips on “the climate crisis (polar ice caps melting, deforestation, major flooding), critiques of the United States Army, and the oversaturation of media” (Mendez 2023). By late 2022, corecore videos had amassed enough of a following and recognition that journalists started reporting on it. Kiernan Press-Reynolds’ account became the blueprint, describing the “anti-trend” trend of corecore as an “algorithmically-generated craze that boils down to an amorphous intangible “vibe,” a free-floating aesthetic with no roots outside TikTok” (Press-Reynolds 2022). Cultural critics, journalists, and everyday TikTok users have debated whether corecore was a profound aesthetic intervention or just elementary shitposting.[2] Press-Reynolds notes that the discourse surrounding corecore has almost been more interesting than the videos themselves: “people argue corecore is more than memes: it’s a politically charged art movement critical of capitalism and technology’s atomizing effect on society. The other camp says the videos are all about surreal humor and vibes; the amorphous essence of subjective interpretation; intangible emotions” (Press-Reynolds 2023). Corecore videos often make either niche sense or too much polemic sense.

Eventually, as is the way of all trends on TikTok, corecore slowly ran its course. Offshoots like #hopecore emerged and they, too, ran their course. Both gave way in late 2024 to a mutt aesthetic—“hopelesscore”—which is known for depicting negative, anti-social, and/or depressive quote animations via fonts and over visuals typically associated with motivation, like footage of a sunset at a beach.[3] As I develop in this essay, corecore gave way to a significant lifeworld, full of substantial audience interest as well as aesthetic appropriation. This ongoing lifeworld suggests that corecore is less a question of signification, or a question of “content” and meaning, and more a rhetorical question of effect and reception: a critical mass of these unruly “anti-trend” aesthetics indicate rhetorical heft and cultural significance at a time when the future of TikTok in the US both as a platform and a political topos remains unclear.

This interdisciplinary essay draws from rhetorical studies, tech reporting, and media studies to argue that corecore could be productively thought of as a contemporary version of the epideictic, which is the rhetorical genre of praising or blaming. In Debra Hawhee’s words, the main objective of the epideictic is “to render explicit something already known, and then to intensify preexisting commitments” (2023, 27). One of the three Aristotelian genres of rhetoric, the epideictic is demonstrative and often ceremonial oratory. The epideictic helps shape “the basic codes of value and belief by which a society or culture lives” (Walker 2000, 9). Common scenes for the epideictic are funerals, weddings, roasts, holidays, and so on. A typical example is someone giving a retirement speech for their colleague. By collectively honoring their colleague’s attributes and past actions, the retirement speech also solidifies that specific community’s (surface-level) majority values vis-à-vis work, career paths, expressions of collegiality, and so on. The conventions and strategies of the epideictic genre are in the service of all parties walking away feeling at least affirmed in their convictions.

For the purposes of this essay, however, I am most interested in the connections between the epideictic and the act of witnessing. Hawhee defines witnessing as “weighty assertions of material presence that lay bare injustices and demand a reckoning” (2023, 8). Witnessing “foregrounds justice and morality,” so “keeping witnessing front and center” is crucial for addressing ecological breakdown (2023, 8). She uses the word “keeping” there deliberately, to be in line with arguments that “identify witnessing as the defining act of our time” (2023, 154). In the face of ecocide and the widespread denial of that ecocide, the act of witnessing is an increasingly salient process by which to respond to—and emphasize—precarity. Witnessing is front of mind for scholars responding to precarity. Current scholarship like Michael Richardson’s Nonhuman Witnessing: War, Data, and Ecology After the End of the World (2024), for instance, expands the scope of traditional articulations of witnessing to include nonhuman witnesses like image recognition systems. In this conception, witnessing is a relational project that necessarily exceeds the “capacity to “know” inherited from Western epistemologies” (2024, 8). The genre of the epideictic both ritualizes and mobilizes that relational project through memorializing, capturing, eulogizing, and bearing responsibility,[4] all of which are essential to witnessing.

Each corecore can be thought of as a witnessing because each corecore is an attempt to make “a core out of the collective consciousness” (Townsend 2023). Aesthetics scholar Mitch Therieau comments that the videos ‘“have a sheen of smoothness and detachment, but it’s like people are screaming underneath”’ (Glossop 2023). Corecore is the dark, ironic -core, documenting and making salient the ecocidal fallout from, in corecore’s POV, digitality: “racial capitalism” (Robinson 1983; Kelley 2017), techno-solutionism (Kneese 2023), cyberlibertarianism (Golumbia 2024), and all the other asymmetries that inhere in how the internet and digital technologies have been both symptoms and drivers of crisis.

And still, while corecore videos are tender, often scrambled efforts, reframing corecore as epideictic witnessing reveals a key yet obscured component: platforms. For this special issue “Critique as Care” in memory of my dearly missed former colleague David Golumbia, “to hold space,” as the CFP asked, “for simultaneity and contradiction,” I want to posit that the opposite of corecore—TikTok LIVE and its commercial livestream program—is a window into how the platform witnesses us witnessing it through such “disobedient aesthetics” as corecore.[5] After all, it would not be a piece in honor of Golumbia without an interrogation of the antidemocratic politics of the technics themselves. I felt strongly about critiquing TikTok LIVE when I wrote this piece in 2024, but in 2025, after the law banning TikTok did not go into effect and US users received not one, but two notifications of shameless propaganda, I feel compelled. Through an analysis of livestream by way of leaked documents, reporting, and outputs, I will suggest that TikTok witnessed corecore through what Anna Munster and Adrian Mackenzie term “platform seeing” (2019), or a platform’s modality of perception “produced through the distributive events and technocultural processes performed by, on and as image collections are engaged by deep learning assemblages” (2019, 10). Through these assemblages, TikTok observed corecore and continues to turn those values back onto themselves. Moreover, these platform-seeing assemblages will always bear witness and therefore always absorb and warp user-generated epideictic truths, which confirms the need to protect platformed epideictic witnessing. In this essay, I articulate the epideictic functionality of aesthetic interventions to claim that they are acts of witnessing. Ultimately, in doing so, I reach for connections between a praxis of care, critique, and scholarly witnessing.

The Epideictic Witnessing of Corecore: Fatigue

Writing about the development of twenty-first century art and performance as they’ve been shaped by digital technology, Claire Bishop states that there are new conditions of spectatorship (2024, 4). Bishop attends to those terrains through examining how attention has been historically and culturally defined as a normative value and practice in relation to art and artistic interventions.[6] Just like media and technologies, we know that art structures ways of seeing that support and run counter to dominant expectations for how to express and cultivate aesthetic taste.[7] “Spectatorial conventions” form from repeated interactions with artistic strategies, “individual inclinations, and unforeseen contextual eventualities” (2024, 35). With this appreciation for the rhetorical contingencies of mediated and distributed attention, Bishop questions whether there is a hierarchical difference between attentional modes. She cites dance theorist André Lepecki (2016) who argues that the “spectators” of social media are more passive than “witnesses:” “only the witness sees the whole performance and is embodied and emotionally in touch with what they are seeing” (2024, 79). With fluctuating conditions of spectatorship, however, it is just not that simple.

Within digitality, hierarchical paradigms of observing do not apply, if they ever did. Social media users are constantly toggling between modes of spectating, from platform specific modes to occasion specific modes, through and beside interfaces. We are at once spectators and Lepecki’s witnesses: such distinctions break down in participatory publics where we are all performing and negotiating multiple appeals to ethos, only for algorithmic visibility filtering to displace or gather views. While detachment is a part of these modalities, social media spectatorship is not reducible to detachment or distraction.

Part of why I was drawn to put the epideictic into conversation with corecore and witnessing is that it offers a figuration of spectating that anticipates these fluid conditions of spectatorship. Intriguingly, the figuration that the epideictic offers is related to theory and theorizing. As Sharon Crowley explains, in ancient Greek the verb theorein meant ‘“to observe from afar”; it refers to someone sitting in the topmost row of the theater. A theorist is the spectator who is most distant from the scene being enacted on stage and whose body is thus in one sense the least involved in the production but who nonetheless affects and is affected by it” (2006, 27). The implication is that distance—distraction, perhaps, or mediation—does not necessarily entail a lessened audience experience. This hybrid, bodily, and slightly detached theorein was precisely what was expected from epideictic audiences. Christine Oravec confirms that theoria—observation—was the “function assigned to the epideictic audience” (1976, 164). The epideictic audience were there to receive the disclosed values and unearthed truths from rhetorics of display: “theoroi means one who looks at, views, beholds, contemplates, speculates, or theorizes. These various translations indicate a kind of insight or power of generalization, as well as a passive viewing” (1976, 164). There were three different varieties of theoria and all invoked a journey: Andrea Wilson Nightingale explains that “the first two involved pilgrimages to religious oracles or festivals and, in the third, the theoros travelled abroad as a researcher or tourist” (2001, 29). Distance and detachment are crucial to all three versions of what Nightingale calls these “envoys” of meaning. Audiences for the epideictic weren’t given an immediate call to arms so much as primed to feel—the warm camaraderie from mutual recognition, certainly, but also an appreciation, both analytic and intuitive, for the artistry of what they were observing.

Scores of scholars have pointed out that the epideictic is a unique and slippery force—it compels engagement with its strange temporality, for instance[8]—but I mainly want to focus on its connection to aesthetics. Dale Sullivan accounts for at least four purposes of the epideictic: “preservation, education, celebration, and aesthetic creation” (1993, 116). Each of these purposes require attention to style; the epideictic rhetor was expected to use “many kinds of amplification” and magnification (Aristotle 1368a). In fact, part of the audience’s job in fulfilling theorein was to observe the rhetor’s skill: was the rhetoric effective at being affective? The audience was invited to “respond to the speech itself as an aesthetic object” (Oravec 1976, 168) by opening themselves up to “the sensory qualities of the speech itself” (Oravec 1976, 163)—the qualities and strategies that most stimulate “through the senses” (Oravec 1976, 171). This nexus of disinterested detachment, sensitized senses, and judgment speaks to a lineage of aesthetics as sensory persuasion, in the doubled passive and active act of beholding: as Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman elaborate, “aesthetics is not only about sensation or receiving information understood as a passive act; it is also about perception, the making sense of what is sensed” (2021, 34). Sensory persuasion encompasses how epideictic amplification makes values and revelations matter.

In sum, the epideictic aims to surface commitments by creating an occasion wherein audiences re-view these commitments through aesthetic sense-making. Aesthetic sense-making is a significant modality for uncovering value paradigms even as they potentially emerge from, or refuse, hegemonic value paradigms. The tension from that relationality produces ambient anxieties and the aesthetic sense-making of the contemporary epideictic are how we might witness those anxieties. Platforms are indeed technologies of control as well as extractive systems—a “hellscape of dreary stimuli”—and still, user-generated epideictic efforts—“an oasis of unthinking vibes” (Press-Reynolds 2022)—bring to light misdeeds and unease.

In response to that “hellscape,” many of us have no other recourse but to bear witness. And in the context of TikTok as in the tradition of the epideictic, bearing witness will always be aestheticized. For example, the main rhetorical strategy across corecore videos is aesthetic juxtaposition. Take this popular corecore video, bookmarked 266 thousand times. It begins with a kid being asked about how much money they want to make when they grow up to which they respond they want to help people feel okay. That innocence influences the viewer to receive every other clip as evidence that we are not, in fact, OK: sped-up footage of a traffic intersection, Ryan Gosling’s character in Blade Runner 2049 screaming, a row of elderly people monotonously pressing slot machines in a casino, and a violent crowd pushing into some big box retail store. The drone of an organ pad orchestrates a melancholic vibe.

The comments on this corecore, as with many corecores, express mutuality—a chorus of users commenting “real” or “thank you” or “this is why…”—because in the truest sense of the epideictic everyone gathered and compelled to receive the display enters a “timeless, consubstantial space carved out by their mutual contemplation of reality” (Sullivan 1993, 128). Although the phrasing of “consubstantial space” might imply a flattening of difference, Jodie Nicotra clarifies that platformed epideictic “does not issue from and to an already-constituted community; rather, by virtue of a process, it enacts a community” (Nicotra 2016). The corecore contrasts are aesthetic stimulants that work to unravel a new-old value, some heretofore muted or jumbled realization on the tip of our tongues. Even with all the alterity of a shifting online “audience,” corecore edits initiate aesthetic sense-making that discover, over and over, one particularly salient shared truth: fatigue.

Fatigue sounds about right because it is right. Broadly, Sianne Ngai notes, “aesthetic experience has been transformed by the hypercommodified, information-saturated, performance-driven conditions of late capitalism” (Ngai 2015, 1). As a result, aesthetic categories and aestheticization are, as McKenzie Wark summarizes, “in-between play and labor, and they signal an era in which work becomes play and play becomes work” (2020, 16). The imperative to self-optimize while negotiating an overwhelming lack of boundaries, infrastructure, trust—the list goes on—is exhausting. Indiscriminate monetization levels all content, and that leveling is traumatizing when political and economic hierarchies could not be more pronounced in most contexts. The constant transmission of Black trauma through the “trope” and “trap” of what Legacy Russell calls the “Black meme” remains especially unbearable (2024, 8). And for a while we spoke to and out of this despair, relying on what Nathan Schneider terms “affective voice,” or the feeling that you are speaking truth to power, which platforms purposefully confuse with “effective voice,” or the actual “instrumental power to change something” (2024, 20). But given years of outrage and never seeing much happen, years of hyper-algorithmic feeds that prioritize hot takes amid the capitalist fracturing of communities and relationships, we’re now plagued with, to borrow from Kate Lindsay, “opinion fatigue:” users are increasingly making “the choice to opt out or otherwise radically alter how they post their thoughts online” (Lindsay 2023). Lindsay speculates that context collapse has been a part of this shift because “Public opinion around a topic can shift but is then sometimes retroactively applied to internet opinions formed long before this new consensus” (Lindsay 2023). It’s all too much. We’re tired.

The aesthetic collisions of efforts like corecore inclined us to witness this ambient anxiety. It’s not that the young and the online are sensitive, triggered by every politically incorrect message. Not even close. Their fatigue is an existential kind of fatigue. Witnessing this fatigue—displaying and holding this fatigue in common—should have been the start of us coming together to agree on one simple point: never again will we let tech companies perform historical reenactments of feudalisms at the expense of our health, our environment, our institutions, our democracies—again, the list goes on. And while fatigue doesn’t seem like the most effective tool for profound witnessing, I’m reminded of Tamika L. Carey’s 2023 Feminisms and Rhetorics Conference keynote in which she draws from Black feminist thought and narratives to trace and reimagine the concept of fatigue. Carey argues that “conversations about fatigue invite us to refine our approaches to listening, to deepen our understanding of relationships, and to invest in reparative practices” (2023, 3). Fatigue, Carey points out, can be marshalled into a resistant form of impatience, or a productive refusal to participate in harmful practices and systems. Fatigue can help us find an in-road into repair: Carey perceives the potential to allow fatigue to orient praxis toward restorative justice, rest, and community-oriented self-care. Witnessing fatigue—really coming to terms with what this fatigue means and how it was wrought—might have been the first rhetorical step toward emancipation from Big Tech. The problem is, they witnessed us witnessing fatigue and they also said: never again.

The Platform Witnessing of Corecore: Engagement

In October 2024, the public was given a rare window into internal TikTok research findings and communications, including information about the degree of effectiveness of remedial measures, how the app more than appeals to young users, content regulation practices, and so on. Fourteen attorneys general led an investigation into TikTok; attendant lawsuits from more than a dozen states claim that the app knowingly hooks children and younger users. Each lawsuit contained redactions due to confidentiality agreements with TikTok. However, the lawsuit filed by the Kentucky Attorney’s General used digital redactions that Kentucky Public Radio could read. These redactions “appeared to primarily quote and summarize findings from internal TikTok documents and communications” (Goodman 2024).

These documents say the quiet part out loud. TikTok’s own research “states that “compulsive usage correlates with a slew of negative mental health effects like loss of analytical skills, memory formation, contextual thinking, conversational depth, empathy, and increased anxiety”’ (Allyn et al. 2024). The NPR report continues: the time limit tool, which lets parents set daily screen time limits, was not implemented to help teens reduce their time on the app. TikTok was curious whether the tool could, in their words, improve “public trust”’ (Allyn et al. 2024). Kentucky investigators also found that TikTok made changes to their algorithm to address ‘“a high volume of…not attractive subjects”’ (Allyn et al. 2024). The algorithm had been retooled to boost content from creators the company deemed attractive. TikTok’s content moderation is faulty and inconsistent. They rely on artificial intelligence for the first go around and human moderators come in “only if the video has a certain amount of views” (Allyn et al. 2024). Internally, TikTok acknowledges “substantial “leakage” rates of violating content that’s not removed. Those leakage rates include: 35.71% of “Normalization of Pedophilia;” 33.33% of “Minor Sexual Solicitation;” 39.13% of “Minor Physical Abuse;” 30.36% of “leading minors off platform;” 50% of “Glorification of Minor Sexual Assault;” and “100% of “Fetishizing Minors” (Allyn et al. 2024). And yet, a presentation for top company officials “revealed that an internal document “instructed moderators to not take action on reports on underage users unless their bio specifically states they are 13 or younger” (Allyn et al. 2024). An unnamed TikTok executive said the reason kids are on TikTok is because the app’s algorithm is so powerful that it “keeps them from “sleep, and eating, and moving around the room, and looking at someone in the eyes” (Allyn et al. 2024).

The technicity of this platform—how it moderates and curates content, how its algorithm (micro)manages what users encounter, and how the interface is designed to prioritize video and deprioritize everything else, including context—is a technicity inseparable from cyberlibertarianism in that those logics have afforded this technicity just as much as this technicity furthers those logics. Golumbia specifies that cyberlibertarianism is not a coherent dogma: just like fascism, many of its tenants and appeals are contradictory. Cyberlibertarianism is, however, a useful concept for identifying doctrine based on “anti-democracy” and pro-corporate foundations (2024, 16): a cyberlibertarian faith in tech wants to reconfigure “social and cultural phenomena into free market terms” (2024, 36) so that it can do away with democratic institutions, expertise, and governments even while claiming such ideals as “democratization,” “community,” “voice,” “access,” and “engagement” (2024, 46). Golumbia explains that this rhetoric looks both ways: “we seem to be talking about copyright, freedom of speech, or the “democratization” of information or some technology. But if we listen closely, we hear a different conversation that questions our right and ability to govern ourselves” (xxiii). Are the conditions on TikTok, for example, democratic if its algorithm places users into “‘filter bubbles’ after 30 minutes of use in one sitting”’ (Allyn et al. 2024)? Can we claim democratic conditions after “As a result of President Trump’s efforts, TikTok is back in the U.S.!” was broadcast on every US TikTok user’s interface?[9]

As I see it, cyberlibertarianism is of a piece of other naming projects that attempt to capture how digitality promotes a deregulated market that will somehow take care of hate speech, disinformation, doxing, AI sludge—everything. Schneider, for instance, argues that the design of platforms is feudalistic because the politics of this design increasingly nudges users “toward autocratic or oligarchic forms of community governance” while simultaneously profiting off their habits and behaviors (2024, 44). I also think of Damien Smith Pfister and Misti Yang’s conceptualization of technoliberalism (2018), which they define as a governing rationality in which digital technologies assume complete democratic and epistemic power to siphon technical expertise and resources while jettisoning democratic opportunities for deliberation. While these concepts have precise histories and trajectories, all three illuminate digitality’s translation of democratic principles into economic imperatives and concentrations of power.

The technicity of TikTok is a product of this twisted cyberlibertarianism x feudalism x technoliberalism collab. It’s the same collab that corecore bore witness to, but it’s also the same collab that witnessed and reabsorbed corecore. Both Hawhee and Richardson note in their work on witnessing that in both senses of the word “arts and acts of witnessing, fortified with the clarifying power of insistence that they gathered over the course of the last century, are expanding to include nonhumans as well as humans” (Hawhee 2024, 4). Witnessing is not a singular project, but something that multiple agents enact. “The human viewpoint,” Joanna Zylinska reminds us, is “precisely a viewpoint”—one of and through many (Zylinska 2023, 129). The transformation and industrialization of vision during the twentieth century turned “vision” into what it is in the twenty-first century: “machine-based process” (Zylinska 2023, 10). Platforms like TikTok “see” through what Munster and Mackenzie call “observation events” that are “distributed throughout and across devices, hardware, human agents and artificial networked architectures such as deep learning networks” (2019, 5). Even without humans and even without datasets of visuals, platforms deploy observation to collect, process, and analyze data. These “observation events” bear witness, a form of “computational spectatorship” (Heras 2019, 180).

Corecore edits were perceived by platform observation assemblages. Composites of cylberlibertarian-feudal-technoliberal logics repurposed corecore creations into acts of platform witnessing. The fruits of the original epideictic witnessing—the value of really dwelling with what collective fatigue might mean, for instance—were seen for what they were only to be absorbed to serve antithetical purposes. As one of the original corecore creators wrote on an Instagram story: “The whole point of this stuff is to create something that can’t be categorized, commodified, made into clickbait, or moderated—something immune to the functions of control that dictate the content we consume and the ideas we are allowed to hold” (Mendez 2023). Although the effects of creating, witnessing, engaging, and circulating corecore can’t all be commodified, these acts of witnessing were still subject to platform seeing. The closest existing theorization of platformed epideictic is Nicotra’s in which she attends to the architecture of mid 2000s Twitter to argue that “epideictic acts of public shaming demonstrate the inexorably technological nature of all rhetorical acts—that the technologies are not separate or supplemental to the rhetorical acts, but are rather co-constitutive” (Nicotra 2016). Attention to technologies is the reason Nicotra refashioned the epideictic, turning what was mostly considered a rhetorical genre into a potential. Unfortunately, the algorithmic systems of platform architectures “tam[e] potential into probability” (Richardson 2024, 87).

If corecore presents one end of a spectrum of TikTok content—as radical as the moderation is going to allow—the opposite end of that same spectrum is TikTok Live and its livestream program, which is widely experienced as the “unregulated underbelly of the app” (Press-Reynolds 2023). For example, Forbes reporter Alexandra S. Levine released a damning account of TikTok Live in 2022—“How TikTok Live Became ‘A Strip Club Filled with 15-Year-Olds”—exposing how the livestream function has enabled predatory behaviors toward vulnerable users. Live is “one of the darker manifestations of the gig economy to date” (Press-Reynolds 2023). Creators want “gifts”—money—and TikTok doesn’t care how they earn that money because TikTok will take a huge cut from every transaction. Press-Reynolds explains that this structure is different from a structure like Twitch where creators build up a fanbase. Fanbases can be built on TikTok, too, but mostly live-streaming creators just throw everything under the kitchen sink to “hook viewers and coax donations” (Press-Reynolds 2023). It is no accident that these “donations” are designed to look like things rather than money: hearts, cars, flowers, animals…many of them are AI slop, from “money gun” for 500 coins to “naughty chicken” for 299 coins. Viewers buy and give these “gifts” for all kinds of reasons, but you can see how the habit of giving could result in chemical responses: will the creator acknowledge me if I send a gift? What about now? What if I send a gift to this creator? Livestream banks on a tempting—and sometimes expensive—mode of parasociality.

Since creators do receive some funds from “gifts,” the BBC reported in 2022 that displaced people and families in Syrian camps were begging for hours at a time on livestream. This begging created a mini economy, with people in the middle supported by “live agencies” in China working directly with TikTok to help unblock accounts while the agents in the middle take a cut of the profits by providing streaming equipment (Gelbart et al. 2022). BBC monitored gift streams of $1,000 an hour, but creators only received a fraction. The reporters note that “TikTok said it would take prompt action against “exploitative begging” (Gelbart et al. 2022), diverting attention away from the real problem.

Users have wildly different experiences on Live, which has produced a variety of what Motahhare Eslami et al. term “folk theories” (2016), or sense-making narratives that social media users form from their experiences on black-boxed platforms. On one YouTube video about the “dark side” of Lives, a user comments that they’ve “seen other types of streams, where a man forces a disabled man who lives in what looks like a hut, to dance to tiktok audios in a dress.”[10] Another writes about one that was streaming, without context, a baby with macrocephaly. One person confirms in the comment section: “I’m from Syria, and yes the situation there is very very very rough, money, jobs, food, water, and electricity are in very very short supply.”[11] In the subreddit r/changemyview, a user writes a post titled “TikTok’s live feature is immoral. It gets clicks by putting disabled people on the feed like animals at a zoo.”[12] This “folk theory” is an attempt to bear witness to what they’re observing. However, someone responded, “this isn’t how that works; the application you were speaking about tends to display content that associates to your previous history/what it thinks you may have interest in.” Someone else writes: “On my TikTok all my lives are musicians and anime cosplayers.”[13] While this particular subreddit is designed to expand and often correct the original poster, such countering and sometimes moralizing of “folk theories” from other users is part of why “disobedient aesthetics” like corecore edits are so vital: they provide another layer of mediation to “folk theories,” toward honoring the ambiguities of platformed living. The long and short of it is that no one has any real idea about how Live works, in general and for other people: it’s sometimes neat (musicians playing the piano) and sometimes cozy (work from home employees inviting body doubling). It’s also unexpected (“Yea this shit is hella weird, i saw one where some guy was just slowly peeling away boiled eggs and kept spamming “tap tap tap tap thank you thank you send gift”) or gives dystopic vibes (“I keep seeing one [sic] with people laying on clinical beds, rocking side to side. My mind takes me to weird places”).[14] Given the structure, we cannot control where we will end up. As one TikTok official stated in the redacted documents, “a major challenge with Live business is that the content that gets the highest engagement may not be the content we want on our platform” (Allyn et al. 2024). Sexualization of teens…refugees begging…babies with macrocephaly—I think I’ve seen this corecore before.

Corecore used aesthetic juxtapositions to reveal fatigue with Big Tech platformization. Those aesthetic collisions intended aestheticism—a more sensitive orientation—through the shock of dissonance and layers of mediation. TikTok used platform seeing to digest these aesthetic collisions, spitting them back out as more monetized livestreams. Those events, however, intended anesthetizing, or the kind of numbing that keeps you transferring funds and doomscrolling. TikTok’s livestreams took the chaotic user-generated epideictic witnessing of fatigue and forced it to become a witnessing of the Big Tech value of engagement. In a turn of events that writes itself, Tim Cook announced the “newest iPad Air” in March 2025 by showing a mock-up “trend report” on, you guessed it, #corecore.[15] Years later and Big Tech continues to commodify what was never meant to be commodified.

Scholarly Witnessing: Care

The 2024 Oxford Word of the Year was “brain rot,” defined as “the supposed deterioration of a person’s mental or intellectual state, especially viewed as the result of overconsumption of material (now particularly online content) considered to be trivial or unchallenging.”[16] At a moment in time when platforms are rolling out AI features that no one asked for and that no one is really ready for, only for AI generated images to become “evidence” of falsehoods,[17] “brain rot” encapsulates a growing, but ironicized concern about the content we’re taking in. “Technolibertarian notions that technologies are value neutral and that information wants to be free,” Jonathan Carter and Misti Yang emphasize, position “the general intellect as a boundless frontier to be exploited” (2023, 367). For “brain rot” to get chosen as the 2024 Oxford Word of the Year means that there is now a much broader recognition of that exploitation. Since aesthetics stick around longer than trends, we’re surrounded by the remnants of witnessing that were unceremoniously churned into revenue streams. Where epideictic content like corecore might have rhetorically positioned us as observers—theoroi—social media rhetorics like the functionality of LIVE position us to rot.

This special issue asked us to bring nuance to critique—to perform scholarly critique from a place of care or caring even while actively discrediting computational solutionism, as Golumbia stressed time and time again. Critique as care is my effort to come to terms with the original display of corecore for what users wanted it to be, not for how the algorithmic systems witnessed and twisted them. Critique as care, then, is an articulation of the scholarly version of witnessing that can bear out from observing—theorizing—user-generated rhetorics as meaningful attempts to navigate unfair power dynamics. By attending to corecore, I extend theories of epideictic rhetoric to better accommodate platformization and its effects on rhetorical acts. By forwarding “platform seeing,” I think alongside Richardson’s question: “If algorithms are themselves witnessing, making knowledge, and forging worlds of their own design, what might it mean to witness their workings?” (2024, 81). In calling attention to leaked documents demonstrating TikTok’s internal culture and praxis, I take seriously Shannon Vallor’s provocation that if Big Tech ultimately remakes our world in its image, scholars might pay for our “habit of epistemic caution with our lives and our children’s futures” (2024, 162). By that she does not mean to undermine best practices for responsible scholarship as much as she means to encourage scholars to, once ready, inhabit force, passion, and courage—to just say, “this is cyberlibertarianism.” And it is fucked. Romeo García and coauthors echo that provocation, writing that “scholars are also guilty—sometimes unconsciously—of re-subjecting those they write and think about to the same epistemic violence they wish to trace, critique, and/or unsettle” (2024, 294). It is not, they write, that the scholar is “the observer merely observing.” Rather, “because the scholar engages in human work (wording) and human projects (worlding), they are indeed active actor-agents who have the capacity to engage in doings otherwise” (2024, 294).

Now would be a good time to quote Golumbia’s close friend, George Justice, who wrote the forward for Cyberlibertarianism. Justice calls Golumbia the “most optimistic pessimist you could ever meet” (2024, ix). He goes on to say that the pages of Cyberlibertarianism “are dark in their insistence that the technologies we deploy in nearly all aspects of our lives have been built on fundamentally antidemocratic, antihuman premises,” and yet the “richness of his thought betrays an essentially hopeful belief in powers of the human mind to contemplate, understand, and attempt to change the world for the better” (2024, ix-x). As a scholar, I have not always understood that you can do both: you can hold these systems accountable and you can still be curious. You can practice sound citational politics and you can hone a unique voice and you can seek traditional venues and you can innovate. Something I have always appreciated about rhetorical training is that it exercises your capacity to find nuance, but in the past that training has prevented me from also finding certainties. I came to Virginia Commonwealth University in 2018, attempting to start a book project that was curious—not certain—about what was happening to opinions vis-à-vis social media. Golumbia, on the other hand, had just published a article earlier that year titled “Social Media Has Hijacked Our Brains and Threatens Global Democracy.”[18] He had already predicted brain rot.

I’m reminded of that expression of two ships passing in the night. But I eventually arrived to a place still informed by care, but very certain that things were as bad as Golumbia had known them to be. My last correspondence with him was to thank him for a talk he did on fascisms and to send a book review I had just written of a rhetorical studies collection on fascism. He was thrilled that I was doing research and teaching about these topics. He wrote, “I would love to talk some of these things over when we both have a free second…,” because while fascism is certain, scholarly care is boundless.

Caddie Alford (she/her/hers) is associate professor of rhetoric and writing at Virginia Commonwealth University. She is a digital rhetoric scholar whose interdisciplinary research examines emergent forms of information, communication, and sociality. Her recent book—Entitled Opinions: Doxa After Digitality—addresses social media rhetorics by creating an affirmative theory of opinions to identify and repurpose a spectrum of truths. Some of her work has appeared in The Quarterly Journal of Speech; Rhetoric Review; and enculturation.

Bibliography

Allyn, Bobby, Sylvia Goodman, and Dara Kerr. 2024. “TikTok Executives Know about App’s Effect on Teens, Lawsuit Documents Allege.” NPR, October 22, 2024. https://www.npr.org/2024/10/11/g-s1-27676/tiktok-redacted-documents-in-teen-safety-lawsuit-revealed.

Allyn, Bobby, Sylvia Goodman, and Dara Kerr. 2024. “Inside the TikTok Documents: Stripping Teens and Boosting ‘Attractive’ People.” NPR, October 16, 2024. https://www.npr.org/2024/10/12/g-s1-28040/teens-tiktok-addiction-lawsuit-investigation-documents.

Aristotle. On Rhetoric. Translated by George Kennedy. 1991. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bishop, Claire. 2024. Disordered Attention: How We Look at Art and Performance Today. Verso.

Carey, Tamika L. 2023. “The Uses of Fatigue: Invitations, Impatience, and Investments.” Keynote Address, Feminisms and Rhetorics Conference. https://cfshrc.org/article/the-uses-of-fatigue-invitations-impatience-and-investments/.

Carter, Jonathan S. and Misti Yang. 2023. “Sophie vs. the Machine: Neo-Luddism as Response to Technical-Colonial Corruption of the General Intellect.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 53:3: 366-378. https://doi.org/10.1080/02773945.2023.2200699.

Crowley, Sharon. 2006. Toward A Civil Discourse: Rhetoric and Fundamentalism. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Eslami, Motahhare, Karrie Karaholios, Christian Sandvig, Kristen Vaccaro, Aimee Rickman, Kevin Hamilton, Alex Kirlik. 2016. “First I “Like” it, then I Hide it: Folk Theories of Social Feeds.” In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’16). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2371–2382. https://doi.org/10.1145/2858036.2858494.

Fuller, Matthew and Eyal Weizman. 2021. Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth. Verso.

García, Romeo, Jenna Zan, Muath Qadous, Mitzi Ceballos, Keith L. McDonald, and Sabita Bastakoti. 2024. “Collective Rewor(l)ding in the Wreckage of Hauntings and Haunting Situations.” In The Routledge Handbook of Rhetoric and Power. Edited by Nathan Crick. Routledge. 293-310.

Gelbart, Hannah, Mamdouh Akbiek, and Ziad Al-Qattan. 2022. “TikTok Profits from Livestreams of Families Begging.” BBC, October 11, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-63213567.

Glossup, Ella. 2023. “Corecore is the Screaming-Into-Void TikTok Trend We Deserve.” Vice, January 23, 2023. https://www.vice.com/en/article/corecore-tiktok-trend-explained/.

Golumbia, David. 2024. Cyberlibertarianism: The Right-Wing Politics of Digital Technology. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Goodman, Sylvia. 2024. “AG Coleman Sues TikTok, Says Internal Documents Show Company Knowingly Addicted KY Youth.” Kentucky Public Radio, October 9, 2024. https://www.lpm.org/news/2024-10-09/ag-coleman-sues-tiktok-says-internal-documents-show-company-knowingly-addicted-ky-youth.

Hawhee, Debra. 2023. A Sense of Urgency: How the Climate Change is Changing Rhetoric. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Heras, Daniel Chávez. 2019. “Spectacular Machinery and Encrypted Spectatorship.” Machine Feeling, 8(1), 170-182. https://doi.org/10.7146/aprja.v8i1.115423.

Kelley, Robin D. G. 2017. “What Did Cedric Robinson Mean by Racial Capitalism?” Boston Review, January 12, 2017. https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/robin-d-g-kelley-introduction-race-capitalism-justice/.

Kneese, Tamara. 2023. Death Glitch: How Techno-Solutionism Fails Us in this Life and Beyond. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lepecki, André. 2016. Singularities. Dance in the Age of Performance. London: Routledge.

Levine, Alexandra S. 2022. “How TikTok Live Became ‘A Strip Club Filled with 15-Year-Olds.” Forbes, April 27, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/alexandralevine/2022/04/27/how-tiktok-live-became-a-strip-club-filled-with-15-year-olds/.

Lindsay, Kate. 2023. “Is it Time to Embrace “Opinion Fatigue”?” Bustle, August 8, 2023. https://www.bustle.com/entertainment/online-takes-twitter-debates-opinion-fatigue.

MacKenzie, Adrian and Anna Munster. 2019. “Platform Seeing: Image Ensembles and Their Invisualities.” Theory, Culture & Society, 36(5), 3-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276419847508

Mendez, Moises II. 2023. “What to Know About Corecore, the Latest Aesthetic Taking Over.” Time, January 20, 2023. https://time.com/6248637/corecore-tiktok-aesthetic/.

Nayyar, Rhea. 2023. “What Does TikTok’s “Corecore” Have to Do with Dada?” Hyperallergic, January 26, 2023. https://hyperallergic.com/795957/what-does-tiktoks-corecore-have-to-do-with-dada/.

Ngai, Sianne. 2015. Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Nicotra, Jodie. 2016. “Disgust, Distributed: Virtual Public Shaming as Epideictic Assemblage.” Enculturation, July 6, 2016. https://enculturation.net/disgust-distributed.

Nightingale, Andrea Wilson. 2001. “On Wandering and Wondering: ‘Theôria’ in Greek Philosophy and Culture.” Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics 9, no. 2: 23–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20163840.

Oravec, Christine. 1976. “‘Observation’ in Aristotle’s Theory of Epideictic.” Philosophy & Rhetoric 9, no. 3: 162–74. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40236982.

Ore, Ersula J. 2019. Lynching: Violence, Rhetoric, and American Identity. Oxford: University Press of Mississippi.

Pfister, Damien Smith and Misti Yang. 2018. “Five Theses on Technoliberalism and the Networked Public Sphere.” Communication and the Public, 3(3), 247-262. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057047318794963

Press-Reynolds, Kieran. 2022. “This is Corecore (We’re not Kidding).” Nobells, November 29, 2022. https://nobells.blog/corecore/.

Press-Reynolds, Kieran. 2023. “Is Corecore Radical Art or Gibberish Shitposts?” Nobells, January 20, 2023. https://nobells.blog/what-is-corecore/.

Press-Reynolds, Kieran. 2023. “I Spent All Night on TikTok Live, and Discovered a Wasteland of Clickbait, Scams, and Other Oddities. It got Stranger and Darker by the Hour.” Business Insider, February 22, 2023. https://www.businessinsider.com/tiktok-live-all-night-clickbait-grifts-scams-sleep-streamers-twitch-2023-2.

Richardson, Michael. 2024. Nonhuman Witnessing: War, Data, and Ecology After the End of the World. Durham: Duke University Press.

Robinson, Cedric J. 1983. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Russell, Legacy. 2024. Black Meme: A History of the Images that Make Us. Verso.

Schneider, Nathan. 2024. Governable Spaces: Democratic Design for Online Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sheard, Cynthia Miecznikowski. 1996. “The Public Value of Epideictic Rhetoric.” College English 58, no. 7: 765–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/378414.

Sullivan, Dale L. 1993. “The Ethos of Epideictic Encounter.” Philosophy & Rhetoric 26, no. 2: 113–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40237759.

Townsend, Chase. 2024. “Explaining Corecore: How TikTok’s Newest Trend may be a Genuine Gen-Z Art Form.” Mashable, January 14, 2023. https://mashable.com/article/explaining-corecore-tiktok https://mashable.com/article/explaining-corecore-tiktok.

Vallor, Shannon. 2024. The AI Mirror: How to Reclaim our Humanity in an Age of Machine Thinking. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vallor, Shannon. 2024. “The Danger of Superhuman AI is not What You Think.” Noema, May 23, 2024. https://www.noemamag.com/the-danger-of-superhuman-ai-is-not-what-you-think/.

Vivian, Bradford J. 2012. “Up from Memory: Epideictic Forgetting in Booker T. Washington’s Cotton States Exposition Address.” Philosophy & Rhetoric 45, no. 2: 189-212. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/475261.

Walker, Jeffrey. 2000. Rhetoric and Poetics in Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wark, McKenzie. 2020. Sensoria: Thinkers for the Twenty-First Century. Verso.

Y7. 2023. “A Postmortem of #corecore.” Flash Art, Summer 2023. https://flash—art.com/article/corecore/.

Zylinska, Joanna. 2023. The Perception Machine: Our Photographic Future Between the Eye and AI. Boston: MIT Press.

[1] Creators were making lip dub videos with the moment in the song when Burnham stages an increasingly frustrated dialogue with himself:

I put the packet on the glass (What glass?)

The little glass dish in the microwave (Got it)

I close the door (Which door?)

The door to the microwave! What is wrong with you?!

[2] “To me, Corecore’s “aesthetic” reads as an art school freshman’s first found-footage project in Adobe Premiere Pro (no, I’m not projecting) presented with the societal dread induced from doom-scrolling on one’s phone at 2am after one too many bong rips on a weeknight (again, not projecting …)” (Nayyar 2023).

[3] For a smart analysis of hopelesscore, see Adam Aleksic’s 2025 substack essay, “How Hopelesscore Became even More Hopeless.” https://etymology.substack.com/p/how-hopelesscore-became-even-more.

[4] Bradford Vivian confirms that witnessing as a mode of communication and rhetorical goal is “generally epideictic in nature” (2012, 191). And as Hawhee writes: “the documentary work endemic to the epideictic genre, in short, serves the rhetorical purpose of witnessing” (2023, 28).

[5] Borrowing apt language here from Anthony Stagliano’s Disobedient Aesthetics: Surveillance, Bodies, Control (Alabama University Press, 2024).

[6] The book’s main project “aims to move beyond the moralizing binary of attention/distraction, to dispense with attention’s economic framing to jettison plenitudinous modern attention as an impossible ideal, and to rethink contemporary spectatorship as neither good nor bad but perpetually hybrid and collective” (2024, 35).

[7] To start, John Berger Ways of Seeing (1972).

[8] As Cynthia Miecznikowski Sheard articulates, “By bringing together images of both the real—what is or at least appears to be—and the fictive or imaginary—what might be—epideictic discourse allows speaker and audience to envision possible, new, or at least different worlds” (1996, 770).

[9] Quote is from the second notification that US TikTok users received on January 19.

[10] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s5Cb6bznQYI&t=319s

[11] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s5Cb6bznQYI&t=319s

[12]https://www.reddit.com/r/changemyview/comments/p95po4/cmv_tiktoks_live_feature_is_immoral_it_gets/

[13] https://www.reddit.com/r/changemyview/comments/p95po4/cmv_tiktoks_live_feature_is_immoral_it_gets/

[14] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s5Cb6bznQYI&t=319s

[15] https://x.com/tim_cook/status/1896951716517662999

[16] https://corp.oup.com/news/brain-rot-named-oxford-word-of-the-year-2024/

[17] https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/ai-girl-maga-hurricane-helene-1235125285/

[18] https://www.vice.com/en/article/social-media-threatens-global-democracy/